9

Essays: Dos and Don’ts

Essays are a critical element of your application and the best opportunity for you to communicate subjective information that cannot be quantified. Consider them as a means to convince the admissions committee about why they should admit you. They are much more important than recommendations and interviews—no recommender can know you as well as yourself and interviews can only answer a few questions in a limited period of time. Essays are the only part of your application that can project you as you think best. They have the potential to bring out your personality, character, values and aspirations in a way that none of the other elements of your application can.

Well-written essays can tilt the balance in your favour despite a low GMAT score, GPA or a career that has involved many switches and, therefore, looks fragmented. In fact, among the top schools, they are almost the only distinguishing element in several applications that are equally good in other aspects.

In order to make an impact on the admissions committee, essays need to be well written, unique, humane and realistic—a tough task. Qualities like creativity, maturity and leadership can be brought out in the essays in your own language. They can give the admissions committee ‘inside’ information about you, going beyond titles and ranks, showcasing, both, your professional and personal characteristics. Qualities such as integrity and honesty can be communicated only here—your test scores and résumé cannot do this. Thus, essays serve as the primary source of information about you. All others are, at best, a means of corroborating or building on information already gleaned from essays.

Essays are also very important from another point of view: they are the only part of your application where labour can bear fruit—there is precious little you can do about your test scores or your GPA, once you have obtained them. Your résumé, too, is more or less what it is, though you could polish it up in many ways. However, essays are answers to open-ended questions and those reading your applications can clearly see your efforts in this area. While the GPA and GMAT do not automatically disqualify you, poorly written essays almost surely will (despite sterling grades and scores). On the other hand, if your essays impress the committee, they might go out of their way to include you despite a low score or a poor GPA or an unconventional background. Every year, schools admit students despite slight weaknesses on one or two fronts—for which they prescribe them pre-term remedial classes. While we have discussed the way to present you in great detail in Chapter 7, it only provided the key points to be kept in mind about the expectations that a school has from a good applicant and well-presented application. Use Chapter 8 to gather the content for your essays in terms of examples from your life and decide a suitable positioning for each of your schools. Once you are done with this exercise and have understood the required criteria in detail, you need to learn to put it all together in your essays.

The Content Of Your Essay

Your essays must aim to answer the specific questions asked of you. While doing this, they must communicate the story of your life—the past, the present and the future—to the admissions committee. They should, therefore, cover not only your professional (or academic) life but also the personal. So how much of the personal and how much of the professional would be right? There are no clear-cut answers. For a typical application, a 3:1 ratio between your professional and personal would be appropriate. If your life story is more about how you survived a tough childhood in a war-torn land and succeeded against many odds in your personal life, it should be given more space.

While it is good to have your essays cover many facets of your life—academic, professional, personal, community work, sports, and so on (as this speaks of a well-rounded personality)—exercise your judgement to see which aspects of your life provide the best answers to the questions posed by the essays. You should not find yourself forcing a topic from a particular facet of life—choose what intuitively appeals to you whether it is from your personal or professional life. This is one of the secrets of a good essay—it has to flow from your experiences in a natural, unforced way. Forcing a formula that worked for someone else on you is the surest way of obtaining a rejection. Use the table developed earlier about the various life experiences here, as it will allow you to find the relevant examples with ease.

Do not waste precious space in the essays by simply paraphrasing achievements mentioned at other places—your résumé, awards and honours. Treat the essays as additional information that you have been allowed to present. Make every bit of this additional material count and remember that in most cases, you also have a word limit to adhere to, making it an even more difficult task.

It would be great if your recommenders can write about and lend credibility to a few incidents mentioned in your essays, but beware of presenting the very same things in both your essays and your recommendations. It simply points to you not having enough experiences to talk about.

Write Outstanding Essays

Although there is no hard and fast rule for writing essays, every person has a style that suits him or her best. The steps mentioned below give a wealth of information culled from the experiences of several successful applicants and offer useful pointers towards crafting impactful essays.

- Attempt all the essays for one school before you move onto other schools. This will help you formulate and refine your positioning. Within a particular school, first attempt the essays that come to you most naturally. For example, an essay asking you to describe an ethical dilemma might appeal to you because you vividly remember an incident of this kind. Strongly appealing topics of this kind make words flow from your pen with ease. Taking them up first will get you into the right frame of mind and get your thought process rolling.

- Make the essay-writing process a continuous one. Great ideas could occur anywhere—not just in the bathroom! Keep a notebook or a word document handy so that these thoughts can be noted down as and when they occur. Also, as you might notice once you start the writing process, you will have periods of creative excellence when thoughts will get formulated with ease and periods when no matter how much you try, writing seems as tough as climbing the Mount Everest. Be sure to make the best use of these creative moods.

- Before you start, have a system in place to store the latest versions of your essays safely, every couple of days—you do not want a hard disk crash or the loss of a diary, setting you back by weeks in the writing process!

- For each essay, first make an exhaustive list of experiences and thoughts that you might want to include without bothering about whether they are the best you can come up with (from Chapter 8). Select the relevant ones later, as and when required. While creating new thoughts and exploring new ideas, the ‘control’ or ‘selection’ factor should be excluded completely. This selection should be done after you have accumulated as many thoughts as possible—this is the best way to generate good ideas for your essays. A sorting of ideas could also be done so that you can identify the really important ones and avoid repetition.

- It is worthwhile to remember that in these initial stages of writing, it is best not to constrain yourself by word limits. Once you are satisfied with the content that you have gathered, you can get into selecting the best parts, compressing your essays and, thus, shortening them to fit the word limits.

- Identify the best ideas. Write these ideas down separately, by grouping related ideas. These groups of ideas will help you outline the essay and develop logical connections between different parts of the essays like what goes earlier, what comes later and so on.

- Once the outline is ready, you can get down to actually fleshing out the sentences. This needs to be done intelligently, as simply getting into the act of crafting sentences before you have decided the broad layout leads to a haphazard organization of randomly written material. Such writing cannot engender a good essay—even with all the editing and refining you might do at a later stage.

- Your first draft should be rough in nature with just enough material to let you understand what you meant when you read it again. At this stage, do not get into perfecting your draft or choosing what words would fit in best. In fact, you do not even need complete sentences. Just the important phrases or keywords will suffice. Put your thoughts down in the most elementary fashion, in the way that they come to you.

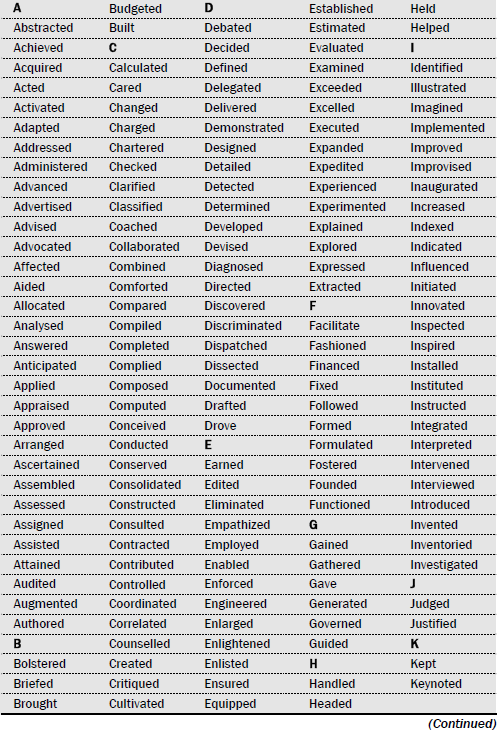

- The second draft needs to be done after a brief gap. A few hours, a day or maybe even a couple of days later would be right. You need to look at your first draft afresh, and gauge if what you have penned down is relevant and if various parts are connected in a logical fashion. Make a preliminary classification of the material into paragraphs and devise an introduction and a conclusion. Now construct your sentences. Here, you should look at your choice of words and elements of style. Your positioning will emerge in this stage. Keep the ten commandments (Chapter 8) in mind while you are at it. Use the active voice instead of the passive. Avoid the continuous tense and avoid paraphrasing the essay questions in your responses. Use more nouns and verbs, especially the so-called ‘action’ words (refer to Table 9.1 provided at the end of this chapter), they make your essay livelier and enjoyable. Reduce adjectives and technical jargon to a minimum. They slow down the pace and using too many of them makes the essay look forced and artificial. Write in a clear, crisp manner that gets the reader interested and involved. Your essay with complete sentences and paragraphs should emerge after this draft.

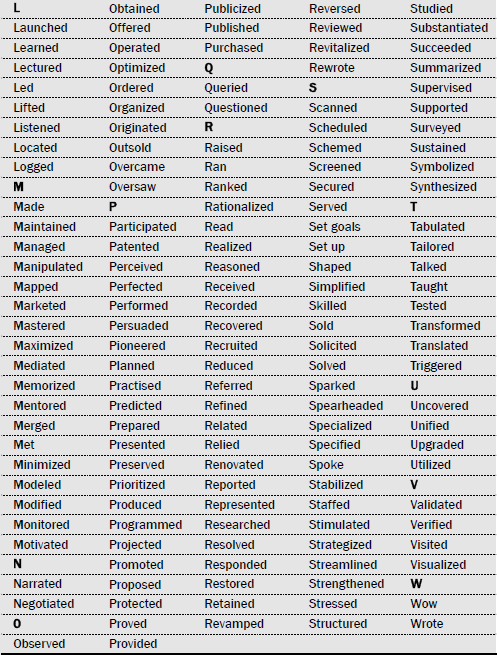

- The third draft should start with a critical analysis of how the material in the second draft is organized. Check that each paragraph conveys only one main idea and is not too long (not more than 150 words). Modify and break down paragraphs if they do not meet these criteria. Ensure that paragraphs logically connect and the transitions are smooth. Scan the list of transition words in Table 9.2 at the end of the chapter to select those words that fit best. Ensure that the same connecting words are not used too often. If the essay is too long (over 500 words), you may consider using headings and/or subheadings. Underlines and italics can be used to focus the reader’s attention on the main points (remember that they would be pressed for time, with several hundreds of applications to be read within a few months). But beware of excessive usage of any of these elements. Also, check whether the formatting and special characters appear as expected in the final online application. While it is important to capture the reader’s attention, it is equally important to hold his/her interest while he/she reads. Consider using a combination of long and short sentences as well as long and short paragraphs. Lastly, your layout should be easy on the eye—preferably with 1.5 or 2.0 line spacing—so do not try reducing the font size in order to adhere to page limits. At this stage, you also need to start looking at the word limits and making necessary changes to conform to them.

- The fourth and subsequent drafts are to improve the quality and tone of the writing and to check the spelling, grammar, punctuation and the word limits.

As you read and re-read the previous drafts, you might come across better ways of presenting what you have said. The introduction and conclusion, in particular, can be made more impactful. Actively look out for these ways of improvement but do not force one just for the sake of it.

Perhaps the best value you can add in these later drafts is that of brevity. Be ruthless and weed out unnecessary words and sentences. It is natural to have phrases like ‘in spite of the fact that’ (replace with although), ‘the question as to whether’ (replace with whether) scattered across the essay. Cut these out and make your essay tighter. This does not mean that all sentences should be made short and paragraphs trimmed. The idea is to make every word count and make the essay a powerful piece of writing. This process also helps you stick to the word limits.

At the end of these, do a final check on the tone of the essay. Make sure you have not used any slang or informal words or phrases. Check for discrepancies that might have crept in because of changes done in the later drafts. The overall tone should be professional, positive, friendly and confident. No part of the essay should betray desperation for getting an admission. Also, questions regarding struggles, failures, or conflicts should never contain anything sentimental or what could be construed as excuses. If you felt sorry for something you did or realized you were wrong, bring it out objectively and mention what you learnt without sounding penitent or upset. Schools are looking for people with strong character who can take personal and professional failures in their stride and learn from them.

- It is now time to get others to provide you feedback on what you have written. There are three ways in which you can get others to help you with your essays, and all the three are strongly recommended.

- Those who know you well can read your essays and give you feedback about whether they can ‘hear you’ in the essays. This is a test of whether the essays truly reflect your personality and character. If they do not, consider revising or rewriting the essays by gathering specific feedback about what your readers find incongruous. Remember that your application, in order to be successful, should be unique and real—and this is possible only by making it match your personality and character as closely as possible.

- The style of your essays—how you choose to present yourself—is as important as the content itself. Invest time in getting your essays checked by experts in language or communication. Approach people who have good language skills and who can give you such advice; these people need not know you well to do this.

- Get one or two current students or alumni of your targeted school to read your essays and give you their honest feedback. This is probably the best kind of feedback you can get regarding the ‘fit’ between your essays and what the school seeks from its applicants. It will also tell you if what you intend to say is actually being heard by the intended audience.

- Be open to feedback and work with your reviewers to improve the essays. Be willing to accept criticism and do not turn defensive. Look out for ways and means to improve the essays to the satisfaction of the reviewer as well as yourself.

- Proofread your essays to eliminate grammatical, spelling, punctuation and formatting errors. Take one sentence at a time, read through it carefully and make sure you have personally checked every word. Do not rely on automatic spell-checks to give you the final product; they can only correct wrong spellings, not wrong or mistaken usage of words.

We do not provide examples for an excellent essay as such, because people have different writing styles and it is not up to us to support any particular way of writing. However, at the end of this book, we have included a few essays of applicants who have been successful in the admissions process at schools such as Harvard, Oxford and others. They all vary in their organization and content, but still, hold true to the main theme of projecting the person as the centre of the universe. Analyse them in the light of the above steps and see for yourself, how an outstanding essay shapes up by keeping in mind the basic rules and following simple procedures.

A Few Must-Haves

- The essays must have you as the subject. Everything you write in your essays must ultimately project you—how you learnt something, how you led a diverse team or how you learnt to speak without stuttering. Remember that you are marketing yourself to the admissions committee, so do not deviate into subjects that don’t do this. Do this marketing professionally and without sounding pompous. For instance, a very common mistake is starting every other sentence with the word ‘I’. This creates an impression of being self-centred. Avoid this when you construct your sentences.

- Admissions committees are usually more interested in the path taken than the goals reached. Every essay that you compose must address this. If you had managed to inspire your team to get a coveted medal, you should bring out how you did this rather than simply extol your leadership abilities and glorify the achievement. Likewise, a lot of data about your accomplishments, no matter how impressive, or a mere list of rewards and honours is not enough to get the admissions committee to consider you favourably. Data alone never got anyone admitted to a B-school. Top schools usually are much more subjective than objective in evaluating your application. They need to see you as a person capable of achieving goals and not the magnitude of goals achieved as a set of numbers.

- Avoid generalizations as far as possible. Being specific lets the admissions committee have a better understanding of you as an individual and this is crucial in making your application stand out. Generalizations, if any, should be supported with specific information. Thus, a statement such as ‘My analytical abilities help me assess tough situations and make sound decisions’ needs to be supported by specific examples of how your analytical powers were put to use in a specific situation.

- The importance of adhering to word limits cannot be overemphasized. A deviation of more than ten per cent on the higher side is permissible in a couple of essays but repeating this in most of the essays asked of you is perceived as inability to play by the rules of the game. Do not risk this. Also, if your essay is much shorter than the prescribed limit, think strongly about the topic and whether you should change it and replace it with something that has more content. If your topic does not give you enough to write about, check for alternative topics if available. If it is a compulsory essay then check if you have actually understood it to be able to answer it in detail.

- Make what you write, believable. Those reading your essays know how things happen in the real world. Avoid using extreme language and superlatives such as best and worst unless these can be substantiated. Also, do not present very one-sided arguments. For example, in an essay where you describe a conflict that you have had with a colleague, do not portray the person as harbouring all the evils in the world. At the other extreme, again, do not make the ending sound like a Bollywood movie where old enemies become best friends for life. The admissions committee is smart enough to know how conflicts are handled and to what extent they can be resolved. Be truthful in what you write and how you write it. It’s got to reflect what happened to you in real life.

- Data, where supplied, should be relevant and the source authentic. Though it is not necessary to quote the source of this data, do your homework diligently. For all you know, your interviewer might decide to discuss some of these data in detail.

- At the cost of repetition, we emphasize this once again: Do not force yourself to write in a style that does not come naturally to you. In particular, do not copy pieces of writing that you have come across anywhere, specifically information from Web sites and books such as this one. Sure, everyone is influenced by what he or she reads or hears. But this does not mean that you should lift ideas or phrases from any source. If you are in doubt, use this litmus test: if you have a book, a Google screen or someone else’s essays open while you are writing, you are heading for disaster.

Common Essay Questions: Dos And Don’Ts

In this part of the chapter, we discuss the most common questions asked by a majority of schools. Remember to look closely at the questions posed by the schools as essay topics. Almost 80 per cent of the topics are variations of the ones discussed below. We do not believe in providing examples of essays written on each topic, but what we do provide are pointers to writing an essay that cover the most ground while avoiding foolish mistakes. We believe that this is the most effective way to help you achieve your goal of writing your own story.

Why do you want to do an MBA? Why from this school? Why now?

Dos

- Make the various parts of your essays coherent. The reason for doing an MBA should fit in with what you have done previously. Do not write that you want to become an investment banker if nothing you have done so far shows either interest or preparation for such a role. Be real and genuine about what you want to do.

- Customize your application to each school. If your school is known for its orientation towards general management, then your reasons for doing an MBA should include picking up general management skills.

- Treat the ‘why now’ question with as much seriousness as the others. Schools not only want to make sure that you have a good reason for doing an MBA but also that this is the right time for it. Applicants with relatively lesser work experience and those with significantly higher work experience would do well to make responses to this question very clear.

Don’ts

- Mention that you are dissatisfied with your current job and, therefore, want to do an MBA.

- Sound unclear about what you want to do in the future. If you have not made up your mind regarding this, we suggest you do it before penning this essay. Force yourself to arrive at a clear short-term and long-term goal. The objective of this essay is to gauge your ability to think into the future in a coherent and realistic way.

- State reasons such as increase in skills, salary or career options among the reasons for doing an MBA. The admissions committee already knows that these are advantages that accrue to every MBA. You should focus on what unique advantages the MBA will bring to you.

- Treat the reasons for doing an MBA as something that can be obtained at other schools as well. You must do your research on what exactly separates the school that you are applying to from the others, and highlight how this matters to you.

What will be your contribution to the school?

Dos

- Determine areas of your skill set and personality that fit in with the class profile and those that bring diversity to it. Address the issue of ‘fit’ first and then show how you would, in spite of fitting into the class, be different from others. If you are an engineer and are inclined towards a career in the technological field, this is a good ‘fit’ for a school like MIT. If you are also an amateur actor, this adds to the diversity factor as this is an attribute few engineers have.

- Look for truly unusual aspects about you—maybe you are a qualified martial arts trainer or a national football player. Or you are unusual by being fluent in five different languages. These might not have a direct bearing on your reasons for doing an MBA, but will help showcase the range of activities that you have engaged in and make you stand out as a person.

Don’ts

- Simply highlight your strongest skills and mention that because you have them you will be valuable to the school. You must look for what you bring to the school that is different from other students.

- Quote qualifications and honours that are already mentioned elsewhere as the reason you are unique. If you want to impress on the admissions committee that you have a great talent for painting, go beyond the awards and recognitions. Explain the reasons for taking up painting, how important it is to you and the like. Remember that you do not contribute by having medals and awards under your belt, you do so by having traits that set you apart from others.

Provide an assessment of your strengths and weaknesses.

Dos

- Be honest in your responses. Do not boast while you describe your strengths. At the same time, do not relegate the weaknesses to just the last few lines of the essay. The school officers look for mature people who can look at themselves and identify both strengths and shortcomings. Strike a balance between detailing the strengths and the weaknesses. This does not mean that you should allocate exactly the same space for both, but as a rough rule, at least a quarter of the essay should address weaknesses.

- Supplement description of your weaknesses with how you have tried to overcome them or reduce them. For instance, if you are poor at negotiating skills you could mention that you have enlisted yourself for courses on negotiation skills. This will project your propensity to improve yourself.

Don’ts

- Simply enumerate your weaknesses and strengths—it is better to give examples where you have demonstrated the qualities. Do not try to cover more than three strengths and two weaknesses. It is more important to let the admissions committee know how you leverage your strengths and how you recognize and address your weaknesses.

- Try and disguise strength as a weakness in a recognizable manner. Beware of purported weaknesses such as ‘I work too hard’ or ‘I pay too much attention to details’; they will not cut ice with members of the admissions committee, unless presented in a manner where you are able to show the negative aspects of the same. If you are not able to think of your real weaknesses (ever heard of narcissism?), try approaching a colleague or a close friend whom you trust to be honest with you. Remember, it’s hard to pull off a stunt like this, so be sure of yourself and have great confidence, if you are doing the same.

- Detail your weaknesses too much. Do not get into describing the problems your weaknesses have caused you or how your career progression slowed down because of them. Mention the key weaknesses, briefly describe how they impacted you and explain how you have tried addressing and overcoming these.

- Mention weaknesses that run contrary to your main positioning. If, for instance, you are targeting a marketing school and are positioning yourself as a would-be marketer, never mention that you are petrified of public-speaking. Your application will not make it beyond the first few reads from the admissions officers.

What do you think are your most substantial accomplishments?

Dos

- Mention accomplishments that matter most to you—they may not necessarily be a big reward or prizes. Explain why they are important to you and how much influence have they had on you. Do not be hesitant of mentioning achievements such as overcoming a handicap or rescuing people from the site of a road accident—they might be personal in nature but will speak for your character and tenacity. A great personality is characterized by small, everyday incidents rather than the one act of saving the national fortune.

- Include events such as overcoming close family problems or traumatic experiences such as death of a parent or a close relative in your essays. Those having gone through experiences such as these almost always write about it, and only appropriately so. No professional achievement can normally affect you as much as deep, personal ones that touch your heart and soul.

Don’ts

- Mention incidents such as graduation or winning a hockey tournament without them being truly important in your development as an individual or a professional.

- Mention a series of events as one achievement. You should try to identify specific incidents in your life that you can write about.

Describe any ethical dilemma that you may have encountered.

Dos

- Choose an incident which is realistic and which genuinely merits the description of an ethical dilemma. Remember the admissions committee is trying to understand your beliefs and value system since the business world today often calls for tough decisions where the mind and heart battle it out. An example would be where you had to debate between promoting your own career interests and that of your more deserving colleague ’s, or where you were faced with a benefit to a loved one, with an ethical cost. Remember, the dilemma can be either professional or personal.

- Strike the right balance between sounding preachy and sounding pragmatic. Remember, you need to describe a dilemma that you faced which challenged your beliefs, and your response to this. Ideally, your reaction should have been that of compassion tempered with reason. The admissions committee is trying to ascertain whether in a sticky situation, you are able to come up with a solution that causes minimal damage.

- If you believe that you have not faced such a situation till now, refrain from making one up to write the essay. Rather, write a note about how you have not faced such a situation, but if faced with one, you would expect a response based on your values and principles and talk about the same in detail. Not everyone has seen death but we all know what it is. You would be greatly respected for speaking the truth and presenting your anticipated actions.

Don’ts

- Choose a trivial event or even one that was transparently unethical in the first place—for example, where you and your colleague were making unauthorized use of company facilities and you later reported this to your boss since your conscience started troubling you!

- Make yourself sound like Mahatma Gandhi’s great-grandchild—the schools are not seeking fledgling angels, but human beings with blood, flesh and guts.

Describe any leadership experience of yours.

Dos

- Understand what leadership is before you start writing. Leadership does not necessarily mean leading subordinates. It is about influencing people—subordinates, colleagues, seniors, clients or others as well as being able to think beyond the obvious and look at the bigger picture. Your focus should be on what you did to bring about this influence.

- Mention various techniques you used to lead—good leaders use a variety of these. Did you coach people? Did you give them a goal to work towards? Did you lead by example? Did you include them in the process and delegate responsibility to them? Or did you coerce people into delivering (remember that the coercive style is also successfully used in times of crisis). Did you confront some or befriend others to influence them? Did you stay ahead of others in visualizing future scenarios and, thus, proved your mettle as a leader? These are indicative (but by no means exhaustive) questions that give you a flavour of what your essays should contain.

- Visualize yourself as a CEO and the qualities you would have to possess if you were one. These would include maturity, foresight, compassion, ability to manage different kinds of people, delegate tasks to them based on their skills and aptitudes, provide emotional support, undertake risks, learn from experience and integrate the efforts of various people to achieve a common goal. Think of incidents that bring out some of these qualities in you.

Don’ts

- Focus too much on the end result of your initiative and gloss over what you actually did in order to make your team successful.

- Get carried away by the technical details of the situation and spend most of the essay describing these. Remember that the context in which your leadership experience happened, whether technical, legal, commercial or any other, is almost incidental. What is critical is the human aspect, how you interacted with others and influenced them.

What matters most to you, and why?

Dos

- Search for a core theme that has propelled your life and, therefore, the most important parts in it. For example, supporting an entire family after the death of one’s father or acquiring knowledge by going beyond one’s immediate socio-economic limitations.

- Explore creative means of linking up various facets if a clear core theme cannot be arrived at. An example can be values imbibed from one’s parents (this could cover work ethic, a philanthropic attitude, love for nature/wildlife and a strong cultural grounding).

Don’ts

- Simply attempt and cover many aspects of your life without a common connecting thread.

- List something like ‘earning more money’ as the connecting theme. Search yourself harder to get to a more meaningful theme, which drives your life. If, however, it really is money that drives you, then go ahead and talk about it.

- Be self-pitying or overly dramatic in describing traumatic experiences or hardships you might have faced.

What do you do in your spare time/hobbies?

Dos

- Select hobbies and activities that you genuinely engage in, that set you apart from others and help you with your positioning efforts. If you are a software engineer who spends most of your time with codes and algorithms, a social activity such as karaoke singing helps project you as having an outgoing personality.

- If your activities are not really distinctive, find something about how you do these activities differently. Maybe you play cricket every night and have actually formed a city-wide club that arranges night matches.

- Communicate enthusiasm and knowledge about your activities in your essay.

Don’ts

- State a long list of hobbies without bothering about whether they help you in strengthening your positioning.

- Resort to clichéd or relatively uninspiring hobbies such as watching TV or going to pubs or pool rooms.

Describe a failure and lessons learnt.

Dos

- Treat the subject matter as one where you have learnt from an incident and hence improved.

- Choose incidents that help you strengthen your position. If you are aiming at a career in marketing, an example of a product failure due to oversight of certain environmental factors can show that you have learnt to look out for such factors in your subsequent product launches.

Don’ts

- Get into details of how you goofed up or how you were oblivious of critical information that caused the failure. Describe the event with just as much information as is required to give you a platform to explain what you learnt and how you have incorporated it in your later endeavours.

- Select a very recent failure. This will not allow you to elucidate how you have been able to incorporate it into your learning subsequently.

Remember that the first step is usually the hardest. Once you have completed the first draft for one of your schools, you would have a better idea of what goes into writing the essays. You would feel more comfortable and confident as you work on the same and improve the drafts over time with each subsequent revision. Also, as you finish essays for one school, go back to the work done during the ten commandments, to look out for your understanding of the next school and your intended positioning for the same. You would be able to use much of your earlier work again, but would have to tailor it as per the requirements of this second school. As you go through the process, you will feel more at ease and by the time you work on your third application, the words would flow and the story would emerge of its own, as you start writing it down.

A word of advice is to be very careful when you finish essays for a school. Along with spell-checks and correction of grammatical errors, it is extremely important that if you are writing an essay for Kellogg, then Wharton should not figure anywhere in the body of the essay. This is a typical mistake which happens when people cut and paste the main idea. The way to get around this is to work on personalizing essays for each school. Add a small statement about the school itself, which will help to showcase your interest in the school as well. Work on the body of the essay. A particular example, which is not of much relevance to school B, should be removed when using the draft written for school A. Sometimes, you will need to expand an example, if the word limit for school B allows it, whereas school A will only allow for a brief mention. Remember that the application process is a significant investment of time as well as monetary resources. Hence, work towards maximizing the impact with each application instead of cutting corners in any of them and trying to get around with little or no work on earlier drafts. It is your application and you need to make sure that you are rewarded for your efforts with an admission for each of your applications.

Table 9.1 Words connoting ‘action’

Table 9.2 Words that can be Used to Bring About a Transition in Ideas

| Continuing a Line of Reasoning | Changing a Line of Reasoning (Contrast) |

|---|---|

| accordingly | actually |

| after all | all the same |

| again | anyway |

| also | at any rate |

| and | at the same time |

| as | but |

| as a result | by contrast |

| basically … similarly … as well as ….. additionally | however |

| because | in any case |

| because of this | in contrast |

| besides that | in reality |

| by this means | in spite of this |

| clearly then | instead |

| consequently | nevertheless |

| first… second…third… | on the contrary |

| following this further | on the other hand |

| for this purpose | still otherwise |

| furthermore | unlike |

| generally… furthermore… finally | whereas |

| hence | yet |

| in addition | |

| in many cases | |

| in the first place… also… lastly | |

| in the first place… just in the same way… finally | |

| in the first place… pursuing this further… finally | |

| in the light of the… it is easy to see that | |

| in the same way | |

| in this way | |

| knowing this | |

| moreover | |

| naturally | |

| next | |

| of course | |

| pursuing this further | |

| so | |

| still | |

| then | |

| therefore | |

| thus | |

| to be sure… additionally… lastly | |

| to this end | |

| with this end | |

| with this in mind | |

| with this object |

Table 9.3 Words that can be Used to State a Sequence of Events

| Sequence/Chronology | Conclusion |

|---|---|

| after | as a result |

| after a few days | as has been noted |

| after awhile | as I have said |

| afterward | as mentioned earlier |

| as long as | as we have seen |

| as soon as | hence |

| at first | in any event |

| at last | in conclusion |

| at length | in final analysis |

| at the same time | in final consideration |

| before | in other words |

| before long | indeed |

| earlier | on the whole |

| eventually | therefore |

| finally | this |

| first… second…third | to summarize |

| immediately | |

| in future | |

| in the beginning | |

| in the first place | |

| in the meantime | |

| in the past | |

| in the same instant | |

| in time | |

| initially | |

| later | |

| later on | |

| meanwhile | |

| next | |

| now | |

| nowadays | |

| shortly | |

| soon | |

| then | |

| to begin | |

| today | |

| until | |

| when |

Table 9.4 Words to Open Paragraphs or State Examples

| Paragraph Openings | Examples/Restatements |

|---|---|

| admittedly | after all |

| assuredly | even |

| certainly | for example |

| granted | for instance |

| no doubt | in brief |

| nobody denies | in conclusion |

| obviously | in fact |

| of course | in other words |

| to be sure | in particular |

| undoubtedly | in short |

| unquestionably | indeed |

| generally speaking | more specifically |

| in general | specifically |

| at this level | such as |

| in this situation | that is |

| the following example | |

| to illustrate | |

| to summarize |