CHAPTER 1

THE EDGE EFFECT

Why Edges Are Powerful

Everyone is looking for an edge, or advantage, in business. How do we win? How do we get ahead? What is the angle that will drive our company’s success? But an edge is not just a term for advantage itself; it can also be the place where you can find that advantage.

We define an “edge” as the outer rim that frames what you do and separates it, quite conveniently, from what you don’t. Edges are frontiers beyond which something changes. When you proceed beyond this border in business, the main thing that changes is risk (see figure 1-1).

Edges are not necessarily clear. To the contrary, many edges are quite fuzzy. When you look to the horizon, are you always sure where the sea ends and the sky begins? In business, strategy edges are like that too. Rare is the exact definition of how a product is positioned, what value a product delivers, or where different customers give a business permission to play. We argue that opportunity resides in this very ambiguity. If its edges are not well defined, a business can redefine them, ever so slightly, in its favor. And by staying within this nebulous but familiar space instead of moving to the less comfortable adjacent expanse or beyond, a business can find brilliant new ways to leverage its existing assets.

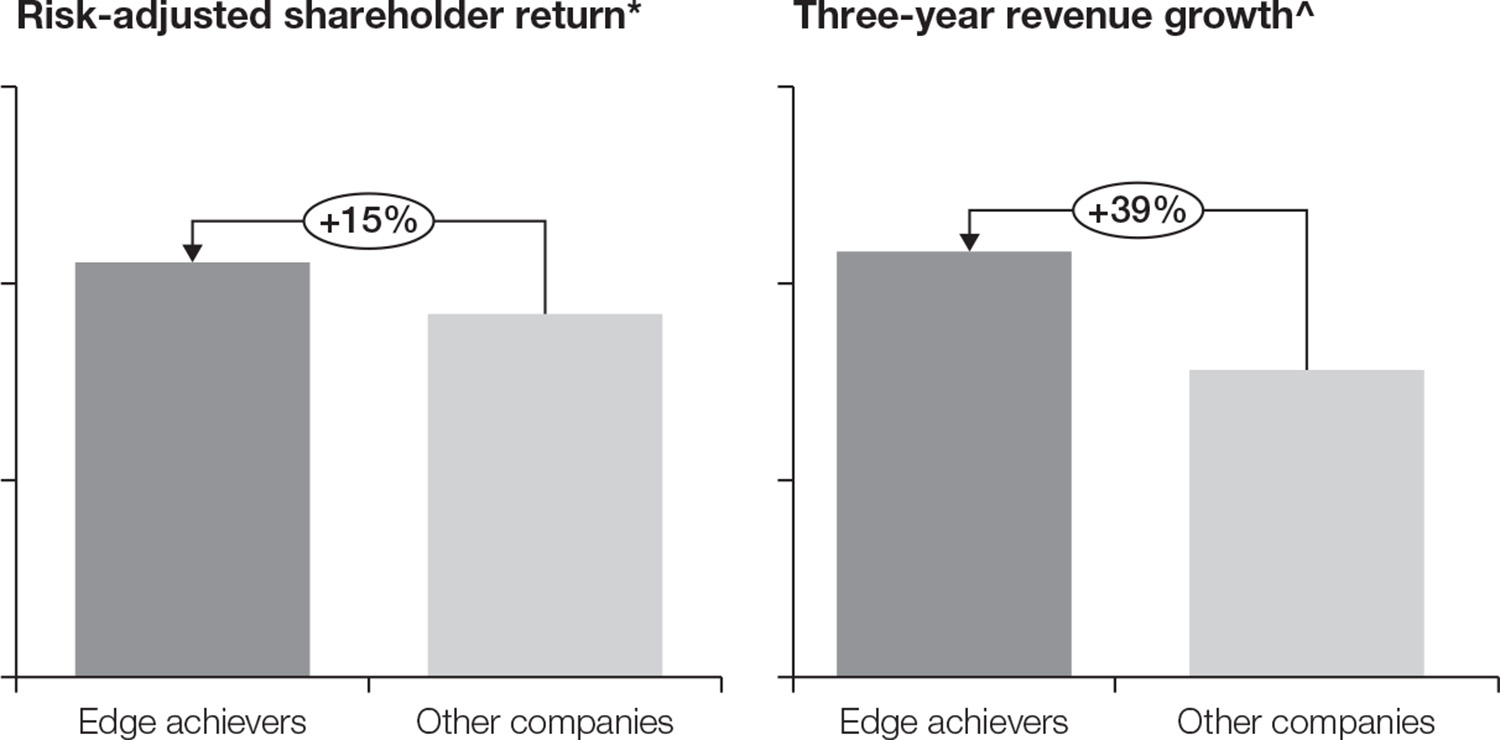

FIGURE 1-1

The outer rim or “edge” of your business

The edge of your business is the delineation of where your current offering begins and ends.

Edges have another interesting property; they are the places where the inside and the outside meet. As such, they tend to be where the action is. In nature, in civilization, and, indeed, in business, the peripheries teem with the most fascinating interactions. Where things meet, opportunities abound. Let’s start there.

The Edge Effect

Ecologists call the phenomenon we just described “the edge effect.” In the 1930s, Aldo Leopold, an American environmentalist, coined the term when explaining why quail, grouse, and other game birds were more prevalent in transitional agricultural landscapes than in single (homogenous) habitats like fields and forests. He posited that “the desirability of simultaneous access to more than one habitat” and “the greater richness of edge vegetation” supported a greater diversity and abundance of species.1

Since then, scientists have given these borderlands a name—“ecotones.” Eugene Odum, whose classic text, Fundamentals of Ecology, helped to popularize this idea in the 1950s, described an ecotone as “an area or zone of transition between two or more diverse communities.”2 He was thinking about the border between forest and grassland or between sea and shore. Places of transition between two ecosystems, such as the edge of forests, shorelines, wetlands, cliffs and mountain sides, estuaries, savannah, tundra, and deserts, are where the greatest diversity and opportunity exist for both flora and fauna. At the edges, the populations, resources, nutrients, lights, and food from both ecosystems mix. Some species exist only in ecotones, given the uniquely fertile environment that the combination of the two worlds creates.3

Odum’s work illuminated why these transitions are particularly fecund and helped explain why 90 percent of marine species live within the 10 percent of ocean nearest the shore.4 But the edge effect also helps to answer other questions that stretch far beyond the natural world.

For instance, why is it that 75 percent of Canadians live within a hundred miles of the US border?5 Here, along a 4,400-mile stretch of land, lies the possibility of doing business with the biggest economy in the world.6 Throughout history, people have focused on edges and built ports—literally, “doors” or gateways—to facilitate trade between different communities that exist on either side.

Karl Polanyi, a Hungarian-American economist, has written extensively on the subject of “ports of trade,” providing detailed explanation of how these locations served to drive the cogs of the economy and commerce from as long ago as 2000 BC.7 These edges are highly varied. Terrel Gallaway, expanding on the work of Polanyi, noted that “[p]orts of trade, like any ecotone, cannot be defined in solely spatial terms.”8 These crossroads also promote the establishment of the enablers of commerce. Some, such as Hong Kong or Singapore, are located on the coast. Others, such as Timbuktu, an old Saharan caravan town linking ancient trade routes, are located on the edge of the desert. Istanbul was built on a border where continents meet—the blurred area that is neither exactly Europe nor Asia, but has a strong cultural influence from both.

It is no surprise that academics draw parallels between the ecotones of nature and the “economic ecotones” of ports of trade and even extend the logic further to the routes that exist between them. Typically, these are also situated at the edges between civilizations. Great trade routes have seeded the major cities of the world and been the conduits for advancement. “Such a river of life as nowhere else exists in the world” is how Rudyard Kipling described the collection of cultural meeting points that make up the Grand Trunk Road.9

Three Types of Business Ecotones

We can also apply this concept of ecotones to individual businesses, to powerful effect. In our work, we have observed that this “transitional bonanza,” this “opportunity between things,” is alive and well at the level of individual corporations. As in nature, these phenomena are often familiar; once recognized, they may even seem obvious. However, before they are exploited, they must be spotted. Consider the many edges that frame a business.

First, there is the boundary where you and your customers come together. Of all the activities that an organization undertakes, this transition is the most important and certainly where all the money is generated. But just like the ecotones we discussed, the lines around a product or service are often imprecise (see figure 1-2). Companies frequently misgauge the desires of their customers, and those customers, in turn, can misconstrue the propositions of companies.

If you have ever been to a theme park or taken a cruise, you will recognize what we mean. While you could consider the booking or ticket of admission as your payment to enjoy all these suppliers have to offer—and, indeed, you have no obligation to spend any more to participate—you know that you are presented with endless opportunities to enhance your experience for a small (or not so small) incremental charge. These companies are masters of navigating the blurred lines around their core product.

Second, the temporal component of this interaction creates its own edges. In our nature analogy, the disruption and coming together, which occurs at the twilight transition between day and night, presents unique opportunities for animals to feed. As a result, a host of mammals, birds, and insects are most active during these times.10 Businesses, too, focus on temporal transitions. The relationship with customers can span everything from an exploratory shopping event to a lifetime of commerce. Even slightly modifying this period of interaction—the edge where the customer relationship begins and ends—is intuitively powerful.

FIGURE 1-2

Opportunities at the edge

The edge of your business is rarely a sharp perimeter but rather a nexus of opportunity.

Consider your own search for food. We expect that if you were in a grocery store today, you wouldn’t have given a second thought to the opportunities such a business has with a product as mundane as lettuce. Yet, someone had the insight to see that the journey to a meal for a customer who buys a head of lettuce isn’t complete: he has to wash it and chop it first before consuming it. This simple insight enabled the transformation of a commodity produce item to a highly profitable prepared food. As we will explore in chapter 3, helping the consumer by going a step further is now an important way that companies like Whole Foods Market have transformed their economics and enhanced their relationship with the customer.

Third, there are all the assets, tangible and intangible, that collectively define a business. These have edges, too. If an enterprise takes careful inventory, it will find that many of the parameters that describe what is core and noncore to its business are equally vague. It may even find that there is some room for interpretation in the very use of these resources and capabilities. In this way, the edges of assets themselves create opportunities.

You may not be surprised that a company like Toyota uses technology it installs in all the cars it sells in Japan to produce data that powers its onboard GPS service. You may be more interested to know that Toyota recognized that the value of this data was not uniquely associated with its primary use. As we will discover in chapter 8, this insight enabled Toyota to successfully launch a new business offering traffic telematics services to businesses and municipalities across Japan using the same data.

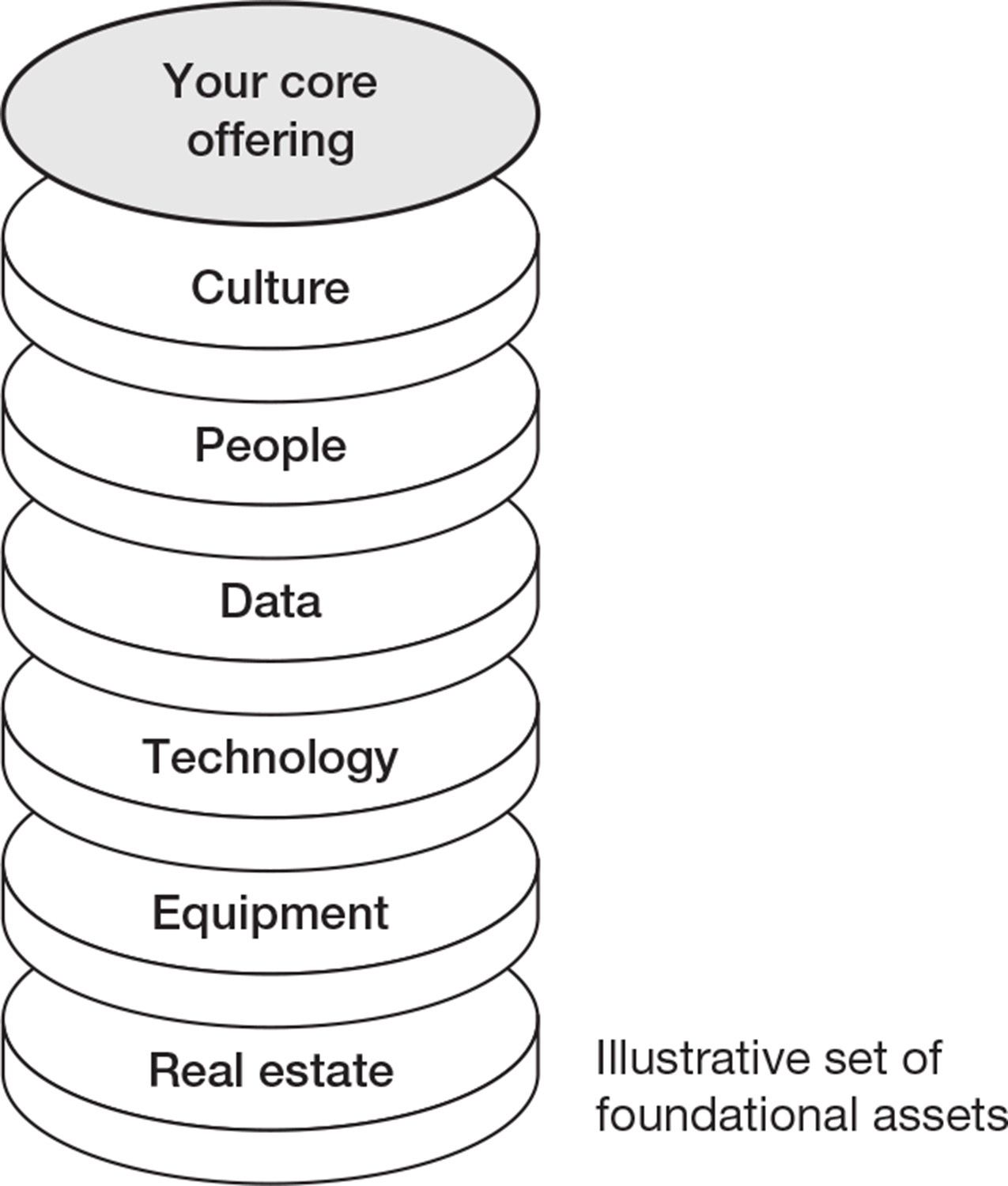

Companies Are Stacks of Foundational Assets

Most corporate mission statements and strategies attempt to answer some variation of the question, “What are we best at?” Firms tend to answer this question—and base their entire identities—by referring to their foundational assets. These can take the form of hard assets, such as a fleet of airplanes or a chain of retail stores. Or they can take the form of more intangible assets, such as smart employees or strong intellectual property based on a given skill.

Every business has a stack of foundational assets that contributes to the delivery of its core offering. At the bottom of this stack are any hard resources that your firm might have: land, buildings, equipment, mining rights, what have you. Above these are typically some softer resources: your labor force, the data you collect, and so on. On top of these lie the capabilities that you employ, the particular skills your company has acquired and honed over the years to make it more effective in its core business. At the top of the stack lies the more metaphysical properties of your organization—the culture, the ethos, the stuff that makes your company unique (see figure 1-3).

FIGURE 1-3

A company’s foundational assets

Your enterprise is built on a unique set of foundational assets to deliver your core offering.

These foundational assets are important. They help form the barriers to entry a company fosters to protect its market share. In most cases, these assets are the basis of how companies compete and seek to differentiate themselves from rival companies; they are the tools of the (win-lose) competition at the core of most corporate strategies today.

Players who invest early and well—or perhaps are a bit lucky—can capture a dominant position in their market that then creates the platform to sustain this advantage, returning the cost of capital and keeping shareholders happy. These are the core strategy winners, the exceptional performers. The first problem is that few (if any) companies are able to sustain core dominance over the long term. The second, bigger problem is that by definition, this route to success doesn’t even apply to most companies.

Rarely do most (if not all) companies realize the inherent value of their foundational assets. Despite their complexity, foundational assets are typically built to execute on a relatively narrow set of activities, delivering the core offering of the company and, ideally, doing so better than competitors. Companies typically devote much less time to additional, creative ways that they can leverage these assets.

Deriving Leverage from Foundational Assets

In our edge analogies, fundamental systems have evolved that allow magic to happen at the places of transition. Life is abundant at the ocean edge because a confluence of interactions there makes gathering nourishment easier.11 The twilight migration creates similar conditions for predators; the relative effort of hunting at a nexus of activity is a fraction of what is required to stalk the forest at a more sedentary hour.12 Converging on a hub like Singapore is a decidedly easier way to trade than to travel to each individual spoke of a merchant network. In all of these edge examples, the common theme is that the system that supports the transition space creates leverage.

In business applications, edge opportunities are precisely focused on gaining this additional leverage. Assembling the original machinery, network, or relationship that makes meaningful results possible requires considerable effort. But once the infrastructure is built, the marginal return from greater utilization is exceptionally high. We will keep returning to this fundamental principle: there is great power in tapping latent potential. When a company identifies these opportunities, unlocking them requires only the incremental cost of modifying an existing system of foundational assets. By contrast, the cost for a new entrant to assemble these same assets from scratch is considerable.

We described three types of business ecotones or situations where edges can occur—in the definition of a product, the nature of the customer relationship, and the use of assets themselves. Each of these interaction spaces is made possible by the foundational assets a company has deployed to execute on its core strategy. The question comes down to where this system of assets can be equipped with more flexibility. Where can these foundational assets be toggled to create options—options that can help you differentiate customers and capture much more than you could with an average solution?

As we’ll see later in this book, companies in industries as diverse as telecom, retail, cruise lines, and medical devices have all created these options. In so doing, they have accessed incremental revenue streams carrying profit margins that are many times what their core businesses realized. This is not magic. It is clever piggybacking on what has largely already been built.

Why Edges Are Less Risky

One of our principle claims is that edge strategies are inherently less risky than many other alternatives a business has to grow revenue and profit. At the surface, this may appear fundamentally at odds with the higher-return characteristics we have outlined.

Part of the reason edges can be simultaneously higher return and lower risk is that the risk is paid for elsewhere. When foundational assets are deployed, in support of the core business, they need to pass their own return-on-investment standard. The investment to establish and preserve foundational assets is typically predicated completely on core performance. Unless a company explicitly contemplated an edge opportunity as an option in the original business model, its discovery is a bit of boon. It requires some incremental effort, through investment or configuration, but more or less benefits from the system of assets that supports the core. In this way, edge opportunities are additional dividends from your core business.

Another reason is that most growth alternatives tend to be new ventures that involve significant uncertainty in the translation of a business case into reality and unforeseen complexities and costs that might arise. It could relate to less predictable market forces, because “new venture” implies that a company has less experience upon which it can rely. Or, quite simply, it could be the greater unknown of how customers will react to a new proposition, a new product form factor, or a new way of engaging through the channel of choice.

Edge strategies face similar uncertainties; the difference is in the degree. First, because edge strategies are aimed at harvesting more value from existing assets, enabling them tends to require a relatively lower level of capital outlay, that is, less new money at risk. This is not to say that they require no investment, but merely that the risk profile is very different from, say, a venture starting without the benefit of the same foundational assets. Second, edge strategy is, by definition, a calibration story. It does not involve stepping out into a new space that is not well understood. It is about reframing or repurposing very familiar interactions in a way that releases pent-up demand.

As such, the endgame of edge strategy is often not transformational, but it is readily realizable in a way that does not compromise the objectives of the core business. As such, edge strategy tends to be an approach that pragmatists favor.

Asking the Right Questions

The goal is to discover new and lucrative ways to monetize your company’s foundational assets. The approach is to look beyond the core business to near-field offerings, where the most leverage (and, intriguingly, the least risk) resides. As with many worthwhile endeavors, the challenge is in knowing where to start.

Frequently, companies focusing on their core business ask themselves: “What are we best at?” This is an important question, of course. But the danger is that it can make the company too introspective, too distracted by its own competencies, and not sufficiently focused on the customer.

To find an edge opportunity, we propose starting with a different set of questions:

- What do our different types of customers want (or need)?

- What could or should our solution include?

- Which of our assets would others value and why?

This framework is competencies-based (inward out) rather than needs-based (outward in), and much more naturally centers on the customer—the absolute key to any profit-expansion effort. It is the best vantage point from which to begin a search. When you review a business this way, in the context of the three types of business ecotones discussed earlier, you orient the process to identify three corresponding types of opportunities. We call these product edges, journey edges, and enterprise edges.

The first, product edges, are the most prevalent. They arise when a product or service is imperfectly calibrated with some customers’ needs. With product edges, an opportunity exists to provide either more or less to certain customer segments in order to better satisfy their overall requirements. Some examples of this might be add-on accessories, complementary services, or options to extend, enhance, or modify a base offer. Each of these strategies creates a better configuration of the core offer for the needs of each unique customer.

The second, journey edges, recast the nature of a company’s relationship with the customer in a way that better maps to the customer’s ultimate objective. We think of customers as being on “journeys”—or missions to do or accomplish something. From this, it follows that any product or service is merely a step along the way to achieving a bigger goal. Journey edges refer to opportunities in which companies redefine their participation in the customer’s journey and expand their solution to encompass needs that either immediately precede or follow the core transaction. For example, when someone buys a flat-screen TV, he has to get it out of the box, assemble it, install it, and program it. In other words, the customer’s journey does not end when he walks away from the cash register with his new TV. Accordingly, options that wrap service around product, anything that turns “do it yourself” into “do it for me,” is a journey edge.

The third, enterprise edges, are the most challenging to find. They are not necessarily intuitive, and an introspective focus on the core can actually hamper the lateral thinking required to identify them. The idea with enterprise edges is to exploit foundational assets in ways that were not foreseen when they were developed to support the core business. Somewhere in the stack of these assets, inadvertent value could be buried. Like other edges, the asset already exists, and under the right conditions, almost accidently, it might enable most of what is necessary to satisfy an unintended need elsewhere. As we will see later in the book, data is an intuitive example. Companies often collect rich data in the process of running their core operation that also happens to be valuable to other companies. As a consequence, it often takes only incremental investment to monetize this value by applying the data in another context.

The Space Between

You may be wondering how this strategic framework fits with others you are familiar with. Simply put, it is complementary. Just as edge opportunities exist somewhere in between your product and what is beyond it, so too should you view the role of edge strategy relative to core strategy and strategies for building new ventures.

You likely employ a range of strategic tools and techniques to expand your market share or to develop new products to pit against your competition. You may also explore opportunities to improve your position on your value chain, better orchestrate suppliers and customers, or gain better access to profit pools. Or you think bolder: making careful decisions to invest in adjacent businesses or new geographic markets. Edge strategy is the third way to explore growth opportunities that introduces opportunities in addition to those your core and noncore strategies might unearth.

Edges Are Everywhere

In searching for edges, we performed a rigorous analysis of some of the world’s largest companies, canvassing the Standard & Poor’s 500, the S&P Global 100, and the Global Dow.13 Our work revealed that product edges were present, at least at a tactical level, in 45 percent of all companies studied. We identified journey edges in 30 percent and enterprise edges in 14 percent (see figure 1-4).14

However, while nearly all of the constituent industries we analyzed showed evidence of some sort of edge, the majority of companies within these sectors did not fully capitalize on the opportunities in their respective spaces.15 We found a small group, approximately 10 percent of companies, that exhibits a consistent ability to find edges and to weave them into their corporate approach.16 These “edge achievers” are also present in nearly every sector.

FIGURE 1-4

Edge tactics by type

Source: Company websites and financials, trade press, and L.E.K. analysis.

*Excludes General Electric, Honeywell, Berkshire Hathaway, Leucadia, Dow Chemicals, DuPont Chemicals, 3M, Danaher, Roper Industries, BASF SE, Bayer, Hutchison Whampoa, Reliance Industries, ICBC, Koninklijke Philips, and Mitsui & Co.

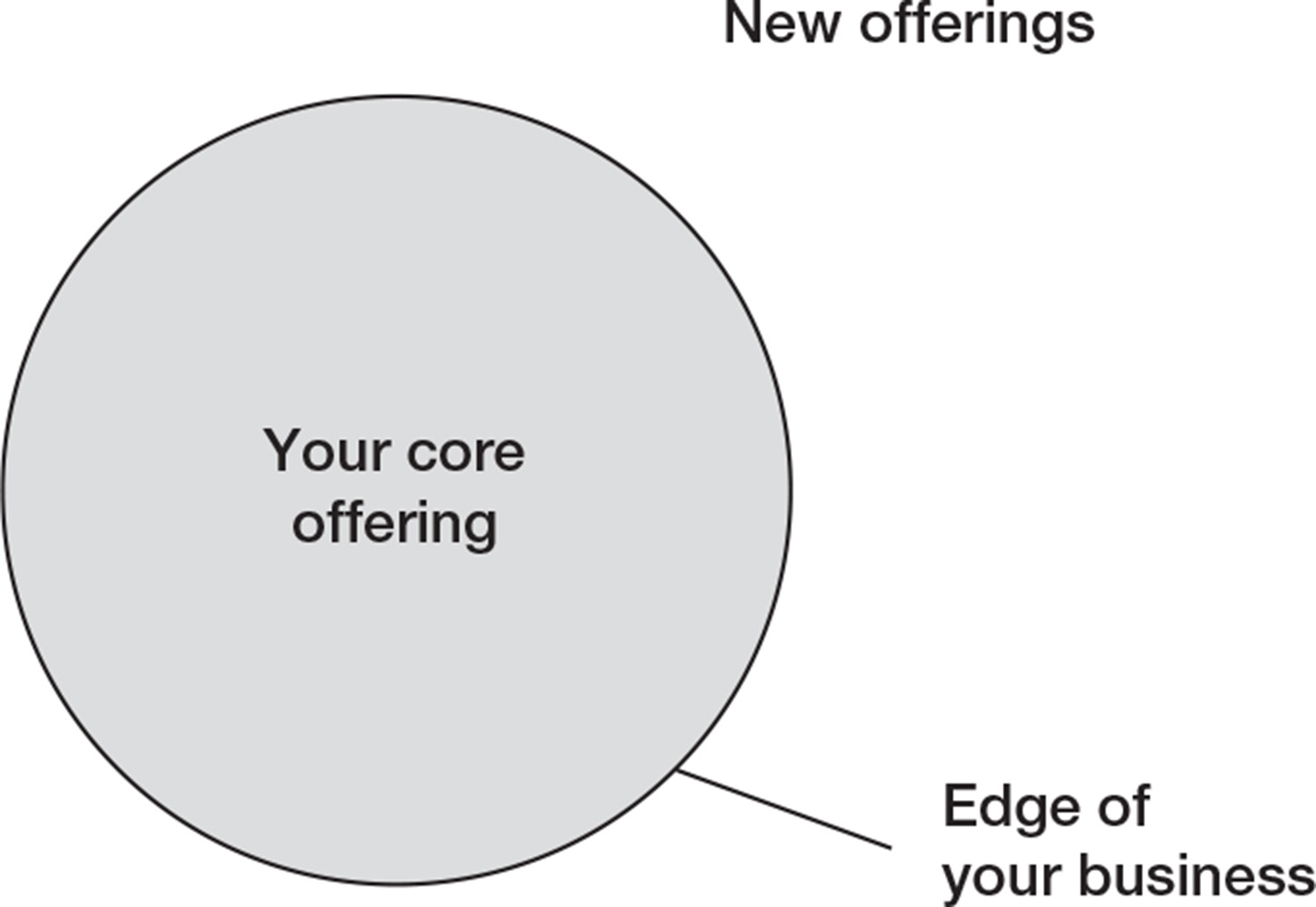

FIGURE 1-5

Returns of edge achievers versus other companies

Source: Company websites and financials, S&P Capital IQ, L.E.K. analysis.

*Sharpe ratio calculated using monthly returns from 1/1/09–1/1/14. The Sharpe ratio is calculated as ((Average Portfolio Return - risk-free rate) / Portfolio Standard Deviation).

^Relative performance calculated as the unweighted average of (company performance / industry performance). Industry performance is unweighted. Only includes industries that contain edge achiever companies. This measure normalizes for inter-industry differences in revenue growth rates.

Note: Industries experiencing negative average growth during this time period were excluded from the CAGR analysis. Excludes: General Electric, Honeywell, Berkshire Hathaway, Leucadia, Dow Chemicals, Du Pont Chemicals, 3M, Danaher, and Roper Industries.

Interestingly, the edge achievers are also the winners. We estimate that these champions of edge strategy have increased risk-adjusted returns by more than 15 percent versus their peers. Furthermore, these companies have outgrown their peers by 39 percent (see figure 1-5).17

We are not asserting a direct causality, as edge strategy is necessarily incremental and is certainly not the only driver of these companies’ success. We do find it striking, however, that those companies that have embraced edge strategy most fully are among those performing most strongly in their respective sectors. Edge strategy is indeed a habit of highly successful companies.

Our conclusion is that while edge opportunities are prevalent, companies do not maximize them. We suspect that this is due to a lack of awareness of the power that edges offer. Absent the right priorities and appropriate attention, and lacking the right mindset, it is hard to stumble on these opportunities by chance. The skill relies on recognizing patterns and asking the right questions.

The Structure of the Book

Half the battle with edges is being able to identify them, so the pattern-recognition metaphor is an apt one. You almost need peripheral vision, as this may involve a slightly different way of looking at your company. But, more than this, you need a new way of thinking about your company. You need what we call an “edge mindset.” What you will get from this book is practice in identifying different types of opportunities, in different situations, and across different types of businesses. We hope some of these patterns will resonate with you and your own business.

With this goal in mind, we have arranged the book’s content into two broad parts. The first part, “The Edge Framework and Mindset,” describes the taxonomy of edge strategy and introduces an organizing framework that runs throughout the text. The second part, “Where to Unlock Value,” applies the edge mindset to some common business challenges and shares our collective experience to guide you in harnessing the power of the edge in your business.

In chapter 2, we introduce product edge strategy. Product edges describe those situations in which your enterprise’s product or service offering is imperfectly calibrated with some of your customers’ needs. As a result, you have an opportunity to rescope the boundaries of your offer in order to better satisfy your customers’ requirements. We use a simple framework to define the overlap between your offer and your customers’ needs and demonstrate how misalignment can create a strategic opening for your business. The chapter also introduces two variants of product edge strategy—outside edges and inside edges—that we address in more detail in the second part of the book.

In chapter 3, we describe the second type of edge strategy—journey edges. We introduce the concept of the customer journey, which proposes that every customer interacts with your business as part of a larger mission extending beyond the four walls of your enterprise. Journey edges refer to those opportunities in which your enterprise is able to redefine its participation in helping complete that ultimate mission. Specifically, the redefinition requires expanding the company’s solution to encompass the needs that either immediately precede or follow the core transaction. We study the example of Whole Foods, an organic grocer, whose prepared-foods category plays a critical role in completing its customers’ mission of preparing a meal.

The first part concludes with chapter 4, in which we examine the third and final type of edge strategy, the enterprise edge. Enterprise edges, the most advanced form of edge strategy, can be found when the enterprise challenges the true utilization of its assets and unlocks value by leveraging those assets’ latent potential in a new product-customer intersection.

These strategies are born from the fundamental question of “who, besides a direct competitor, would pay for the rights to any of my foundational assets?” We expand on this concept of foundational assets to illustrate how enterprise edge opportunities derive economic leverage by selling access to the foundational assets in a way that does not detract from the core offering. We conclude the chapter by taking you through three surprising case studies that illustrate the basic tenets of enterprise edge strategy.

In our treatment of all three types of edge strategy in the first part, we emphasize that they are incremental in effort, clearly leverage foundational assets, and are appended naturally to the core transaction as options. Furthermore, throughout these early pages, we have included an array of quantitative and descriptive evidence, collected from our comprehensive review of edge strategies across three major global equity indexes in order to further support our framework.

Chapter 5 begins the second part of the book by focusing on effective upselling. We discuss how you can use product and journey edge upselling to satisfy the customers’ common desire of wanting something better. This type of edge-driven upselling is distinct from basic merchandising strategy (the well-worn “good, better, best” playbook); it encourages adoption of unique, separate add-on options that slightly redefine the customer-company relationship in a way that feels natural and makes the customer more satisfied.

The second half of the chapter offers a structure to help explain when and where upselling can be most effective. We profile six types of edge-based upselling and pair these with basic customer needs (convenience, comfort, relief, peace of mind, passion, and knowledge). We also use a detailed case study of a true upselling master—Royal Caribbean Cruise Lines—to extract some best practices. The chapter concludes with a discussion of how you can best present upselling options to your own customers.

Chapter 6 presents edge strategy in another practical context: dealing with margin pressure. The chapter begins by acknowledging an uncomfortable truth that faces many businesses: in all likelihood, some of your customers are unprofitable. It then tackles how edge strategy can correct the customer-profitability equation. A form of product edge strategy (the “inside edge”) is particularly effective here; it allows you to “de-content” your offering so that the base version is more profitable for all customer segments, while simultaneously not alienating your most valuable customers. To reinforce this point, we use examples of how industries including airlines, gas stations, and medical devices have used this approach to maintain profitability in the face of stiff economic headwinds. The chapter concludes by discussing how a nonprofit deployed an inside edge strategy to mitigate the impact of budgetary pressure facing many public schools following the Great Recession.

Chapter 7 aims to help combat commoditization; specifically, it focuses on using edge strategy to drive marketing effectiveness. We discuss how to use options as a faster, less risky, less capital-intensive way to reposition products and sharpen differentiation. The chapter focuses on leveraging multiple product and journey edge strategies to communicate the value of ancillaries. We work stepwise through the application of an edge mindset to the otherwise familiar tools of customization, solutions, and bundling. The chapter concludes with a simple framework, the “edge merchandising matrix,” that helps brings these concepts together holistically.

Chapter 8 discusses how the advent of big data has enabled edge strategy for many businesses. The exponential growth in the amount of data that businesses collect and use has created a challenge—and opportunity—for many. Companies that are using data to power their edge strategies are finding new and creative ways to create value; our research uncovered a broad range of emergent examples. This chapter surveys the various ways in which data can enable these edge plays and why many companies (not just cutting-edge technology firms) can monetize this value by renting access to more tech-savvy, sometimes unconventional users.

Chapter 9 begins by summarizing a well-known phenomenon: mergers and acquisitions often destroy value. We discuss how Imperial Chemical Industries PLC fell from a market cap of nearly $10 billion to complete dissolution in a decade. Given that deal success is commonly banked on the promise of new revenue, we advocate an edge-based perspective to validating these synergies. We demonstrate how the biotech industry has been more edge-oriented in its pursuit of deals than the big pharmaceutical companies and, in particular, how Gilead Sciences was able to string together highly accretive, edge-oriented deals. We use the example of Best Buy’s Geek Squad to elucidate how deals themselves can sometimes be used to seed and accelerate edge strategy.

Finally, in chapter 10, we recapitulate our key learnings and present a ten-step process to identify and activate your edge strategy. It represents—in abridged form—the accumulated wisdom of our three decades of experience helping companies find their edge.