Chapter 3

How Shall We Know Success? Alternative Ways of Developing Criteria for Judging the Effectiveness of Educational Programmes, with Reference to PSHE

James, M. (1995) ‘Evaluating PSE and pastoral care? How shall we know success?’ In R. Best, P. Lang, C. Lodge, and C. Watkins, (eds) Pastoral Care and PSE: entitlement and provision (London: Cassell): 249–265.

Any kind of development that is important enough to promote is important enough to be assessed in some broad sense of that term. If one knows what personal development means, then one must have some rough idea of what counts as having achieved it in some respect. One must be able to state what counts as appropriate evidence of success. It is therefore important to attend to the ways in which both the school and the individual are succeeding – the school in helping the individual to develop as a person, the individual in his or her own personal development. If it is argued that personal development is much too subjective or private an affair for any form of assessment, then one should retort that it is much too subjective or private an affair for the school to get involved in. But that is not to say that personal development should be assessed through tests or examinations. It does mean that one has to make judgements, and that to make judgements one needs to think by what criteria and on what evidence one is to make them.

(Pring, 1985: 139–40)

Before I begin I should say that this is not a ‘How to do it’ chapter. My intention is not to offer a framework or recipe for evaluation but to explore some issues about how the quality of PSE and pastoral care might be judged. The emphasis is on the process of delineating criteria and deciding what kind of evidence it would be appropriate to collect. I have no interest in making dogmatic statements about what I think should count as good practice because I prefer, for the purposes of this chapter, to explore the value pluralism that characterizes this area, as it does all areas of education. By remaining agnostic, as it were, I hope to show just how important are the decisions that need to be made by stakeholders about what constitutes quality in PSE and pastoral care and how debate about, and development of, success criteria are a vital part of any evaluation – perhaps the most vital. It is in this process that the questions of what is of value, what is worthwhile and what is good practice are addressed. After all, it is this act of valuing that distinguishes evaluation from research which sometimes aspires to be value- neutral.

Unfortunately, and perhaps surprisingly, questions about judgement are not well dealt with in the evaluation literature. Most texts, including the book that I co-authored (McCormick and James, 1983, 1988) and the only book on the theme of evaluation in pastoral care (Clemett and Pearce, 1986), give more space and attention to the important technical and ethical issues associated with evaluation roles, data-collection methods, analysis and reporting than to the difficult conceptual questions associated with developing criteria for judgement. This can contribute to an impression that evaluation is essentially a technical and strategic enterprise. It is all this, but it is also about engaging in principled debate at the most fundamental level – about the aims and purposes of PSE and pastoral care and the extent to which educational provision promotes their fulfilment.

With this in mind I propose to begin my discussion by outlining the kind of criteria that might define success in PSE and pastoral care. I identify three broad categories of success criteria:

- success defined by the quality of student outcomes (outcome criteria);

- success defined by the quality of student experience (process criteria);

- success defined by the quality of the environment for learning and change (context criteria).

In relation to each of these categories, I will describe some approaches to evaluation that have the capacity to provide the kind of evidence to which these criteria might be applied. In doing this, I will also try to identify the particular opportunities or difficulties that arise when applying these approaches in the field of PSE and pastoral care.

Approaches defined by student outcomes

Outcome criteria

If the purpose of certain forms of educational provision, whether through specific courses or more generalized whole curriculum approaches, is to develop in youngsters certain behaviours, skills, attitudes or understandings, then it would seem logical to delineate what these outcomes should be. The success of provision would then be judged according to the extent that youngsters demonstrate what they know, understand and can do. The attitudes they display may also be considered important outcomes. Evaluation of educational provision is therefore achieved through assessment of student achievement. This is the classical approach to evaluation in many western societies and is currently embodied in National Curriculum assessment in England and Wales; league tables of aggregated results of assessments are regarded by government as the most important measures of the effectiveness of teachers and schools. Interestingly, this link between students performance and school effectiveness is not taken for granted in all societies. In Japan, for instance, despite an inordinate amount of testing, there is no assumption that student outcomes are a reflection of the quality of the curriculum or teaching (see Abiko, 1993). Students are held to be more accountable for their results than either their teachers or their schools.

The argument for giving priority to outcome criteria are usually considered to be very strong in our society. In the context of PSE and pastoral care, therefore, it is often claimed that there is little value in educational provision that does not result in recognizable improvements in students’ understanding, attitudes, skills and behaviours. For example, if teenage pregnancy, racial harassment and bullying show no signs of improvement after extensive programmes to address these issues, then there would be justifiable cause for concern. If the purpose of PSE and pastoral care is to promote student development, learning or change, it seems reasonable to expect that provision should be judged according to whether it achieves this aim. The implication for evaluation is that judgement of effectiveness is based on the analysis of student outcome data. The mode is outcome evaluation.

Outcome evaluation

Traditionally, outcome evaluation has been associated with a particular model of curriculum and teaching which assumes that planning begins with the specification of objectives for student learning. Sometimes these can be quite broad but often they are defined in terms of precise student behaviours, such as demonstrating through writing that they know certain facts, or displaying particular skills. The objectives are often set by ‘experts’ (in the case of the English National Curriculum by subject working parties) and the task for the school is to plan schemes of work and to provide teaching to give students the best opportunity to achieve these objectives. Student outcomes are then measured, by assessment techniques, to determine changes in knowledge, attitudes and behaviour. The success of the educational programme (the intervention) is therefore judged according to the extent to which student outcomes reflect the pre-specified objectives. The objectives therefore become the criteria for success.

This objectives model of curriculum planning and evaluation has always been popular both at the level of theory and in teachers’ common practice. It has been challenged, particularly in the 1970s (more of which later) but it is currently experiencing a resurgence in the shape of the National Curriculum for England and Wales. To date, the model is strictly applied only to the core and foundation subjects but it will be interesting to see whether the cross-curricular themes, dimensions and skills (some of which overlap with PSE and pastoral care) will eventually be viewed in this way. There is considerable precedent for this, particularly in relation to health education which was one of the five cross-curricular themes to be identified by the National Curriculum Council (NCC, 1990). I shall use health education as an illustration here, and elsewhere in this chapter, partly because I have had some involvement in evaluating it but also because health education is often incorporated into programmes of PSE (or vice versa). I recognize that the relationship between the PSE and health education is problematic, so I should make clear that what follows is not an attempt to equate them, although some writers have sought to do so, or to argue for priority to be given to one rather than the other.

On the whole I take the view that PSE is the broader area although this depends on a particular view of what health education is. Definitions of health education have varied from the broad to the comparatively narrow. Some are so broad as to encompass PSE, if not the whole of education. Katherine Mansfield’s definition of health is often quoted: ‘By health I mean the power to live a full, adult, living breathing life in close contact with what I love . . . I want, by understanding myself, to understand others. I want to be all that I am capable of becoming.’ The definition given by the World Health Organization in 1946 was almost equally broad: ‘Health is a positive state of mental, physical and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.’ In both cases the aim is so broad, and deep, that the extrapolation of measurable outcomes becomes exceedingly difficult and threatens the feasibility of evaluation within the classical objectives model. To delineate operational objectives for measurement purposes would undoubtedly trivialize the aim.

It is clear that educators often work with a much narrower definition of health than that given above. Beattie (1984) has identified four approaches which may be identified in health education:

- education for bodily regulation

- education for personal growth

- education for awareness of the environment and political limits to health

- education for community action on health.

These can be handled alongside one another, with schools giving greater or lesser emphasis to each dimension according to their circumstances. In this way the four approaches can be related, rather than polarized, as in some of the literature.

However, when confronted with the problems associated with drug abuse, teenage pregnancy and the exponential spread of HIV, definitions become narrowed again. Faced with these immediate threats to the well-being of both individuals and society, the pressure for educators is to intervene to bring down morbidity and mortality rates. A social consensus in support of this is assumed and liberal arguments for the individual’s right to choose are not always considered relevant in these circumstances. Nevertheless, the ‘intervention’ often targets individuals, and particularly their cognitive or affective faculties, in order to persuade them of the need to change or modify their behaviour in a direction that accords with current ‘expert’ knowledge. Many health promotion campaigns are of this nature and some, it has to be said, are highly successful. For example, on the day that I wrote the first draft of this chapter (9 October 1992), the newspapers reported that the Foundation for the Study of Infant Deaths claimed that a 35 per cent decrease in sudden infant deaths (cot deaths) between 1988 and 1991 was likely to be attributable to a Reduce the Risk campaign, which was launched in 1991 to disseminate new advice through television, doctors and health visitors. The evidence on which this claim was based was essentially epidemiological: mortality rates were monitored and, on the basis of statistical probability, changes had been associated with the intervention. The procedure was little different from the evaluation of the efficacy of a new drug, except that a control group was lacking which reduced the certainty with which cause and effect could be established. Not surprisingly, this approach to intervention and its evaluation is sometimes referred to as ‘the medical model’.

In some circumstances, the effectiveness of educational programmes in terms of changes in knowledge, attitudes, behaviours and disease rates can be established with even greater apparent certainty through what is known in the jargon as a ‘quasi-experimental non-equivalent control group design’ (Campbell and Stanley, 1963; Bynner, 1980). In simple terms, this means that two groups of students, with roughly similar characteristics such as age, sex, social background, educational attainment and school experience, are chosen but only one group is exposed to the programme that is to be evaluated. The performance of students who have followed the programme can then be compared with the performance, on the same measures, of the control group. Inferences about the effectiveness of the programme are then made according to whether statistically significant gains are registered for the ‘treatment’ group over the control group.

This was the main approach to evaluation adopted in two dental health programmes with which I was associated in the early 1980s (see Dental Health Study, 1986; James, 1987). The programmes were curricular programmes available for use by teachers in schools but they were sponsored by the then Health Education Council whose Dental Health Advisory Panel was the steering group for the project. This panel was largely made up of dental and medical professionals who were predominantly concerned with the reduction of disease through encouraging preventative behaviours. Their medico-scientific training also led them to expect rigorous evaluation along the lines of the medical model with which they were familiar. Therefore, continuation of funding became dependent on the provision of reliable information about improvements in children’s knowledge and attitudes (as assessed through structured interview and questionnaire) and behavioural outcomes (as assessed through clinical examination to give measures of plaque deposits and gingival bleeding). The extent to which any improvements were attributable to the programme was determined by the use of ‘control groups’ in schools which had not, at this point, been offered the programme.

In both the cot deaths campaign and the dental health programmes some of the messages were relatively simple (sleep your baby on its back; brush your teeth and gums regularly) and some of the effects of behavioural change were observable in a relatively short time. For example, brushing quickly reduces gingival bleeding – an indication of gum disease. However, in many areas of health education, and in PSE and pastoral care more generally, it is not easy to measure outcomes or even define, in precise operational terms, what they might be. What, for instance, would be a reasonable expectation of measurable student outcomes from teaching or counselling about personal relationships, HIV/AIDS, citizenship or environmental stewardship? The scope of PSE is much broader than that which can easily be measured. Furthermore, many behavioural outcomes will truly be demonstrated only in the real-life choice situations that children encounter in late adolescence and adulthood.

Attempts have been made to predict outcomes reliably from what people say that they intend to do in certain future situations (Becker, 1975; Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975). Thus measures of knowledge, understanding, intention and attitude, rather than explicit behaviours, become the focus of outcome evaluation of educational programmes. However, there is always some doubt about whether the intention to act in a certain way will, when circumstances arise, lead to the desired action itself. One of the main difficulties with the outcomes approach framed in this way is that it often assumes that individuals will make rational choices on the information available when the time comes. It therefore ignores or minimizes powerful social constraints on an individual’s freedom to act.

There are other problems too. First, there is the question of whether social consensus on what outcomes are worthwhile can be assumed. In some circumstances the right of an ‘expert’ group to impose its definition of the situation on others poses both political and ethical questions. For example, programmes promoting birth control raise such questions if they fail to address underlying issues associated with poverty. As Williams (1992) has pointed out, ‘sexual activity and parenthood are two of the few aspects of life in which the poor can achieve some form of parity with the rich’ (p. 281); children are still ‘poor men’s riches’ in many late-twentieth-century communities.

Second, if outcome data are taken to be the sole indicators of the success of PSE and pastoral care, it is unlikely that satisfactory explanation will be found for failure if the objectives are not achieved. This has a crucial bearing on the usefulness of evaluations. In its pure form the objectives–outcomes model treats the intervention (programme and processes) as a kind of ‘black box’ since what goes on inside it is not scrutinized. Attention falls only on the objectives for the programme and what it appears to achieve. How objectives are achieved is of little interest. The assumption is that what needs to be done if the programme fails to do what it was intended to do will be self-evident. It is worth noting that this seems to be the assumption underlying National Curriculum assessment. Given the specification of objectives in the form of statements of attainment, it is assumed that knowledge of whether children have achieved them or not will be the key to future curricular planning. However, as Simpson (1990) has argued, if we wish to find out why children have failed to learn certain things we need to know how they have learned what they have actually learned. In other words, if we want explanations for particular outcomes we need data about processes (of both teaching and learning) and criteria with which to judge their worth.

Third, there is the question of whether it is ever possible to attribute outcomes unequivocally to a particular intervention. Since students are not rats enclosed in mazes but human beings who are exposed to rich and varied material and social environments, there is always the possibility that the outcome might have been brought about by something else entirely. In this is a strong argument for making sure that the intervention or teaching programme is worthwhile as an experience in its own right.

If, as argued above, there are a number of objections to an exclusive focus on outcomes as indicators of quality in PSE and pastoral care, are there alternatives? The next section examines the possibility of developing and using process criteria as a conceptual basis for evaluation.

Approaches defined by student experience

Process criteria

Like outcome criteria, process criteria, which have reference to the quality of educational experiences, are derived from underlying models of curriculum and learning. For this reason their formulation can be equally problematic. For example, if educators believe that the only thing that stands in the way of an outcomes approach is the fact that students are not likely to encounter the relevant ‘real-life’ choice situation for some years (for example, preparation for parenthood) then the curricular programme, and the way it is taught, might be very similar to the objectives approach outlined above. In other words, facts and information might be presented to students in line with current expert knowledge. Understanding would be encouraged through illustrations of hypothetical or real-life situations, and students might be encouraged to develop decision-making competence in line with the instruction they have received. Again the appeal would be to the individuals’ cognitive faculties on the assumption that when the time comes they will make rational choices. In this case, process criteria relating to the educational experience might look something like this:

Students should have an opportunity to:

- listen and pay attention to the teacher;

- work in an orderly and quiet atmosphere;

- be given correct information and explanations;

- be given or shown evidence of ideas in practice (perhaps through examples of what is likely to happen if certain courses of action are, or are not, followed);

- receive clear guidance on how they can avoid problems encountered in ‘real life’;

- demonstrate that they have absorbed and understood the instruction they have received (orally or in writing).

This, of course, will be instantly recognizable as the traditional ‘transmission model’ of teaching and learning. An alternative model, with which teachers involved with PSE and pastoral care will be familiar, is the ‘self-empowerment model’. This is less ‘content-centred’ and more ‘learner-centred’ and aims to encourage the development of personal competence, self-esteem and life-skills (including decision-making), through experiential learning strategies. In so far as the aims are about personal growth, the precise long-term outcomes for any individual are difficult to define and predict. Again the most realistic approach, for the purposes of evaluation, may be to focus upon the educational experiences that students are given access to, and to judge the quality of these. The process criteria within a self-empowerment model of curriculum and learning might therefore look something like the following:

Students should have an opportunity to:

- encounter a problem (perhaps through the use of stimulus material, such as a trigger film, an extract from a television programme, a dramatic presentation, a newspaper article or fictional narrative);

- gather information on the problem for themselves (by investigating what constitutes the problem, who is affected, and how it develops, perhaps by using libraries, making inquiries of specialist agencies, conducting mini-surveys);

- discover and disclose their own values and feelings in discussion with one another (probably requiring group work in which certain ground rules are clearly articulated and understood – concerning the importance of listening, being supportive and respecting others, not interpreting others’ experiences for them and not being judgemental);

- propose a number of alternatives for action that take account of people’s different values, different personalities and abilities, different cultures and different social and material circumstances;

- consider the likely consequences of each course of action, especially the reactions of others (which requires empathy and imagination);

- decide on a course of action and try it out with someone who will give feedback (perhaps through role play);

- evaluate whether the decision was wise or appropriate (perhaps in whole class discussion, small group work or through written work).

(adapted from James, 1987)

What I hope will be clear from this discussion is that the precise formulation of process criteria depends on a fundamental analysis of what counts as worthwhile curriculum experience for students. This is a form of curriculum deliberation (intrinsic evaluation) which needs to go hand in hand with empirical data collection and analysis (empirical evaluation).

Process evaluation

Whatever process criteria are arrived at, and whether their identification precedes or follows the collection of evidence, the fact that they have reference to the educational experiences of students demands the collection of data that are very different from the data appropriate to outcome evaluation. What is needed are data about curriculum materials and classroom processes and techniques for analysing it.

During the 1970s, as the shortcomings of outcome evaluation became known, there was a tremendous growth of interest in process evaluation in Britain, in North America and in Australia. A reader entitled Beyond the Numbers Game (Hamilton et al., 1977) was pivotal in the international debate among professional programme evaluators. At the same time Lawrence Stenhouse in Britain was looking at similar issues in the development of his concept of ‘teachers as researchers’ in their own classrooms (Stenhouse, 1975; Rudduck and Hopkins, 1985). At both levels, the move was away from developing ever more sophisticated techniques for the measurement and testing of student outcomes, and towards greater use of the data-gathering methods previously associated with ethnography and social anthropology – observation, questionnaires and interviews, journal keeping, photography and document analysis. As Parlett and Hamilton (1972) argued in their manifesto for ‘evaluation as illumination’, the need was for greater understanding of the ‘instructional system’ and the ‘learning milieu’, that is, the processes and contexts for learning.

As a result of this new orientation, the 1980s saw a growth in publications, projects and in-service courses which aimed to give the necessary research skills to those who wanted to engage in enquiry into classroom experience (for example, see Burgess, 1985; Hook, 1985; Hopkins, 1985; Nixon, 1981; Walker, 1985; Walker and Adelman, 1975). In essence these all advocated the adoption of a research perspective on classroom and curricular processes so that the ‘black box’ might be opened up to scrutiny. The intention was to enable teachers to make judgements about the effectiveness of curricula and teaching on the basis of evidence that did not depend solely on data about student outcomes.

In terms of the techniques available for data-gathering, the emphasis shifted from the use of assessment instruments, often dependent on quantitative analysis of students’ written responses to prescribed tasks, towards collecting qualitative data through direct observation of classroom processes or talking with teachers and students about their classroom experiences. If one takes the process criteria set out above, the appropriate evidence for determining whether these had been achieved would probably take the form of observational data of what actually happened in the classroom, or participants’ perceptions of the impact of what happened. This more qualitative approach to the evaluation of PSE and pastoral care has characterized a number of fairly recent substantive studies. For example, the national evaluation of active tutorial work located itself within the ‘illuminative paradigm’ (Bolam and Medlock, 1985, p. 4); the data collected were qualitative rather than quantitative and drawn from observation, interviews, questionnaires and document analysis.

Of particular note has been an increasing recognition of the importance and value of eliciting students’ views of their experience (Ellenby, 1985; Lang, 1983, 1985; Thorp, 1982). In my own early evaluation efforts, as a secondary school teacher of social studies and PSE, I discovered that talking with students about their experiences of the curriculum provided the kind of insights that enabled us to rethink provision (James, 1980). It might seem rather obvious to ask students about their views but until recently this source of evidence was neglected. Lang (1985) attributes this neglect to the dominance of the teachers’ perspective although, for a long time, all kinds of data involving people’s perceptions or personal judgements were suspect because the dominant positivist paradigm of research claimed that the validity and reliability of findings depended on so-called ‘objective’ measures. Yet common sense tells us that perceptions count; ‘If people perceive things as real, they are real in their consequences’ (Thomas, 1928).

The assumption behind all approaches to evaluation is, of course, that if evidence (of whatever kind) and judgements indicate that something needs to be done – to improve students’ educational experiences or to bring about the desired outcomes – then action will be taken to improve the existing situation. In both outcome evaluation and process evaluation the focus of attention is generally at the micro level, on individuals and classrooms. This assumes that any action for change will take place at this level, most obviously by adapting teaching programmes so that they might become more effective in process or outcome terms. But process evaluation, like outcome evaluation, can fall into the trap of ignoring social constraints on the development of personal autonomy and decision-making competence. A moment’s reflection is usually sufficient for us to realize that, in order to bring about desired change in individuals, or to empower them to take control over their lives, action may need to be taken to remove barriers to the exercise of individual freedom. And these barriers are often located in social structures, at the macro level. For example, however successful teachers appear to be in motivating individuals to eat a healthy well-balanced diet, to stop smoking or to disclose bullying, little is likely to be achieved if the diet proposed is beyond a family’s economic means, if children are being (insidiously) bombarded with contradictory messages on smoking from a powerful industrial lobby (and government is perceived to take a passive stance towards this) and if social codes and values are not taken into account over issues involving disclosure. There is an argument therefore for turning the evaluation spotlight on structural and environmental barriers to change. According to this argument the success of programmes of PSE and pastoral care might reasonably be evaluated according to the extent to which such barriers have been removed or overcome.

Approaches defined by the environment for learning

Context criteria

The case for shifting the focus of attention from the individual and the classroom to the social structure of nations and communities is a radical one. In the field of health education it has been debated extensively (see Tones, 1987) and contributed in the mid-1980s to some shift of interest away from health education per se towards more emphasis on health promotion (although there were more conservative interests operating in this direction as well). This also influenced some reconceptualization of success criteria towards consideration of the extent to which the following promote or hinder the achievement of health goals:

- mass media and marketing strategies by industry;

- the provision of public services and incentive systems;

- organizational and community development and change;

- economic and regulatory activities;

- local and national legislation.

Here attention is focused at the macro level, so one might reasonably ask what the implications might be for school- level health education, PSE and pastoral care. After all, teachers and schools can hardly be expected (for political and practical reasons) to take on governments and multinational corporations and be judged by the results. It would contravene the principles of natural justice to hold them accountable for change which is beyond their power to effect, except in minimal ways. Yet surely schools are still expected to have a role in promoting personal and social development in a context of structural constraints. And there is some expectation that these efforts will be evaluated. It seems to me that the response to the evaluation problem is, as in the previous two approaches outlined above, rooted in a view about what constitutes an appropriate curriculum in this context.

In relation to school health education, Tones (1987) outlines what he calls a ‘radical’ approach. This is an approach, not a curriculum as such, but the elements of a planned curriculum might be extrapolated from it:

the main function of education is considered to be that of ‘critical consciousness raising’ (a process which has an excellent educational pedigree – originally in the adult literacy field [Freire, 1972]). People should first be made aware of the existence of the social origins of ill health and then should be persuaded to take action. According to Freudenberg (1981) health educators should ‘involve people in collective action to create health promoting environments’ and should help people organise ‘to change health-damaging institutions, policies and environments’ (Freudenberg, 1984). This might, at first sight, seem far removed from the concerns of health education in school, but . . . a combination of social education and lifeskills training as a precursor to ‘mainstream’ health education may lay the foundations for such radical activities. However, before any such action is feasible, people must believe that they are capable of acting. In other words, they must come to accept that they have the capacity to influence their destiny and acquire the social skills to do so.

(Tones, 1987: 11–12)

Tones’ view of social education and life skills as a foundation for ‘mainstream’ health education is highly problematic. So is his advocacy of a ‘self-empowerment approach’ to school health education as the appropriate model for curriculum in this context. If this alone were adequate then effectiveness might be judged in terms of the criteria set out in the previous section, which would allow no distinction from the process approach previously discussed. The focus would remain at the level of the individual and interpersonal interactions and would not pay sufficient attention to environment change, which is claimed to be the major rationale for the approach. It seems to me that the so-called ‘radical approach’ demands that both curriculum and evaluation should focus deliberately on ‘critical consciousness raising’ and ‘collective action to change environments’. Therefore the criteria by which this approach might best be evaluated would probably be a combination of process criteria and outcome criteria: concerning the development of individuals and groups in terms of self-esteem, life skills, critical awareness of social constraints on action, and their capacity to work collaboratively towards action with some attention to the results of such action. This last criterion might reasonably be assessed in school settings in limited ways since, as sociologists of education have shown, there is much in the structure of schools and the ‘hidden curriculum’ that obstructs the achievement of educational goals. Students might be encouraged to address these issues, and the results could be monitored. To take one small example, again from health education, the recent demise of the tuck shop can in many schools be attributed to students realizing and taking action to reduce the mismatch between what they learn in lessons and what the school promotes in other ways. The key evaluation question implied here is: ‘Is this a health-promoting school?’. This can be widened to ‘Is this a healthy school?’, at which point it resonates with ‘Is this an empowering school?’ which is a central evaluative question for those who promote whole-school approaches to pastoral care and PSE. In relation to all three questions, answers probably require an analysis of process, outcome and contextual data and the relationships among them.

Although, in the radical approach, outcome, process and context criteria are all considered to be important, the key concepts are ‘critique’ and ‘action’. For this reason the mode of evaluation with which this approach is often associated is known as critical action research.

Critical action research

Critical action research is not a new approach but has a history stretching back almost fifty years. Its origins are usually associated with Kurt Lewin (1948) who worked with minority groups to help them overcome barriers of caste and prejudice. His ideas have probably been taken up and extended most effectively in the field of development studies (that is Third World development). However, they have also had an impact in the field of education, although, in their most radical form, more at the theoretical level than the practical level (Carr and Kemmis, 1986; Oja and Smulyan, 1989; Elliott, 1993; McKernan, 1991).

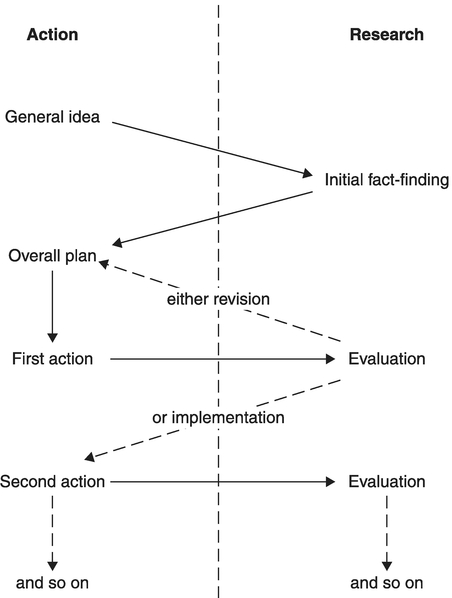

In essence, the central idea is that action and research should proceed together hand in hand. (This contrasts with conceptualizations of evaluation as a ‘bolt-on’ to the main activity.) There have been a number of attempts to represent the action research process in diagrammatic form (see Ebbutt, 1985, for a review). Most have been successful only in confusing would-be participants and convincing them that the process is esoteric; instead of empowering them it threatens to make them even more authority-dependent. Cognisant of this danger, I am hesitant to offer a further such representation. I therefore offer Figure 3.1 merely as a means of showing how the two key elements are integrated. The assumption is that participants (students and teachers in the school situation) begin with some idea about what is wrong and what they might do about it (a general idea). They then go about finding out more including whether their assumptions are justified (fact-finding). On this basis they devise an overall plan which they break down into action steps. They try the first step out and evaluate the results. This may lead them to revise their overall plan or it may give them the confidence to go on to the next action step. The action they next take will also be evaluated as it is implemented. This pattern would be repeated until the ultimate goal is felt to have been achieved. In this way, evaluation is not a ‘bolt-on’ but becomes an integral part of the development process. If evaluation is a fundamental part of the process, it also follows that it should not be delegated to a specialist ‘evaluator’ but should be taken on by the collaborative group of participants. The logical implication for schools that choose to adopt this approach would be that both teachers and students should be involved, as well as any consultant whose specialist skills might also be enlisted. The emphasis here is not so much on specific methods (qualitative and quantitative techniques of assessment, observation, interviewing might all be useful) but on the evaluation strategy. In order to maintain coherence, the evaluative element of action research has to involve all participants, including students, in an active way, not merely as research ‘subjects’. I have to admit that I can find few references to examples of this approach in practice in British educational contexts although the work of Jean Rudduck (1990) provides a notable exception. There have been numerous educational projects which describe themselves as action research (such as the Ford Teaching Project and the Teacher Pupil Interaction and the Quality of Learning Project, directed by John Elliott, and the more recent Pupil Autonomy in Learning with Microcomputers Project, directed by Bridget Somekh) but these have mainly defined the participant group as teachers and educational consultants. Students have provided data but have not been centrally involved in conducting the research. In the examples given, this may be legitimate because, despite their titles, the focus was actually on teachers and the constraints on their action. However, if interest shifts to the learning and empowerment of students, and structural constraints on their freedom of action, then it follows that the participant group should be re defined to include students who would need to be involved in all the decisions about, and processes of, evaluation. In many ways this would represent a fundamental shift in our view of what constitutes evaluation and who does it. If worked out in practice it could be very exciting and thoroughly educational. But this radical approach is, by definition, also highly political, which is probably why examples cannot easily be found.

As I mentioned earlier, there was once a time (in the mid-1970s) when I was a head of social studies in a secondary comprehensive school. One of my abiding memories is of being hauled over the coals by the headteacher who viewed my

practice of getting students to do little social investigations of their own as a threat to the status quo in the school. One cold day when the boiler had broken down the girls decided on collective action (to sit down in the school playground) to try to persuade the head to allow them to wear trousers. I was attending an in-service course on that day but when I returned it was made quite clear to me that this kind of action was perceived as directly attributable to my teaching. Although I was not accused of making school uniform a particular focus, the head implied that making students aware of social constraints on action (some of the content of social studies courses at that time) and giving them the skills and confidence to investigate and act in the social environment was politically unacceptable. Above all, students were expected to be docile – to obey the rules – as they are in many schools and much of society today.

If one adopts a radical approach to curriculum and evaluation, one needs to be aware of its political consequences; by definition it is likely to disturb the status quo. On the other hand, one can argue that all approaches to evaluation are likely to do this, in some measure, if they are genuinely concerned with ‘finding out’ and not merely exercises in post hoc rationalization for decisions already made.

Conclusion

In drawing distinctions between evaluation approaches based on different conceptions of what might count as appropriate criteria for success in PSE and pastoral care, I am aware that what I have described may be perceived as mutually exclusive alternatives. Methodological purists might indeed say that this is the case, arguing that each of these approaches is grounded in a distinct epistemological tradition which is theoretically incompatible with the others: positivist social science in the case of outcome evaluation; interpretative social theory in the case of process evaluation; and critical theory in the case of emancipatory action research (see Carr and Kemmis, 1986, for the clearest account). However, evaluation, whilst having a theoretical dimension, is essentially a practical activity, and the long-established criterion of ‘fitness for purpose’ may yet be the best guide to choosing the most appropriate strategy and methods for evaluation in a specific context.

For example, in areas where there is acknowledged social consensus, where objectives for learning and change can be clearly defined and where outcomes can be accurately measured and attributed to a specific educational programme with some certainty, then outcome evaluation might be very appropriate. Where these criteria cannot be met then another approach might be called for. Best of all might be an approach to evaluation that attempts to tap all the relevant dimensions – outcome, process and context. As long ago as 1967, Bob Stake wrote a paper called ‘The countenance of educational evaluation’ which still provides perhaps the most comprehensive answer to questions about what we should attend to in evaluation. He said that any educational programme should be fully described and fully judged and that this description and judgement should relate to antecedents (including environmental influences on teaching and learning), transactions (processes) and outcomes in the widest sense (immediate and long-range, cognitive and conative, personal and community-wide) – and the relationships that can be found to exist among these dimensions. This still stands as an ideal for a comprehensive evaluation. However, alongside this ideal one has to bear in mind the practical and resource implications of trying to investigate all these things.

Although many evaluations aspire to be multi-dimensional and comprehensive, practical constraints usually mean that priorities have to be decided. The outcome of these decisions usually endows evaluations with a particular (and inevitably skewed) character. For example, the national evaluation of pilot records of achievement schemes (see Broadfoot et al., 1988), on which I worked from 1985 to 1990, set out to investigate all aspects of the phenomena called records of achievement, including their effects on students’ self-concepts and self-esteem and attainment. However, methodological and resource limitations led us to decide to concentrate our efforts on investigating content, process and context. Our case studies provided rich information for helping to frame policy (which was our brief) but they were unable to provide unequivocal evidence about student outcomes. We would argue that techniques for doing this were simply not available. However, a residual feeling remains that, had we been able to provide ‘hard’ evidence on this dimension, government might have made a more committed response.

Evaluation, then, is an inexact science and is likely to remain so. In the area of PSE and pastoral care, as in general education, its value rests on the quality of the judgements that are made about the appropriateness of approaches to particular contexts. This calls for basic thinking skills as much as for the specialist skills of the social investigator or test expert. Indeed, since no educational programme is quite like any other, the idea of ever producing a foolproof technical manual is likely to remain elusive. These insights should convince people that evaluation is not an ‘experts only’ activity but one that teachers, students and others can participate in at all levels. But they need to see the point of it; their views need to be taken seriously; and they need help to develop skills of deliberation on the basis of evidence.

References

Abiko, T. (1993) Accountability and control in the Japanese national curriculum. Curriculum Journal, 137–46.

Beattie, A. (1984) Health education and the science teacher: invitation to debate. Education and Health, 2(1) 9–16.

Becker, M. (1975) Socio-behavioural determinants of compliance with health and medical care recommendations. Medical Care, 13, 10–24.

Bolam, R. and Medlock, P. (1985) Active Tutorial Work: Training and Dissemination: An Evaluation. Oxford: Blackwell.

Broadfoot, P., James, M., McMeeking, S., Nuttall, D. and Stierer, B. (1988) Records of Achievement: Report of the National Evaluation of Pilot Schemes. London: HMSO.

Burgess, R. (ed.) (1985) Field Methods in the Study of Education. Lewes: Falmer.

Bynner, J. (1980) Experimental research strategy and evaluation research designs. British Educational Research Journal, 6(1), 7–19.

Campbell, D. and Stanley, J. (1963) Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research on teaching. In Gage, N. (ed.) Handbook of Research on Teaching. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Carr, W. and Kemmis, S. (1986) Becoming Critical: Education, Knowledge and Action Research. Lewes: Falmer.

Clemett, A. J. and Pearce, J. S. (1986) The Evaluation of Pastoral Care. Oxford: Blackwell.

Dental Health Study (1986) Natural Nashers: Evaluation Report, Dental Health Study. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Department of Education (mimeo).

Ebbutt, D. (1985) Educational action research: some general concerns and specific quibbles. In Burgess, R. (ed.) Issues in Educational Research: Qualitative Methods. Lewes: Falmer.

Ellenby, S. (1985) Ask the clients! Pastoral Care in Education, 3(2), 144–9.

Elliott, J. (1993) What have we learned from action research in school-based evaluation? Educational Action Research, 1(1), 175–86.

Fishbein, M. and Ajzen, I. (1975) Belief, Intention and Behaviour: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co.

Freire, P. (1972) Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Freudenberg, N. (1981) Health education for social change: a strategy for public health in the US. International Journal of Health Education, 24(3), 1–8.

Freudenberg, N. (1984) Training health educators for social change. International Quarterly of Community Health Education, 5, 37–51.

Hamilton, D., Jenkins, D., King, C., MacDonald, B. and Parlett, M. (eds) (1977) Beyond the Numbers Game: A Reader in Educational Evaluation. London: Macmillan.

Hook, C. (1985) Studying Classrooms. Waurn Ponds, Victoria: Deakin University.

Hopkins, D. (1985) A Teacher’s Guide to Classroom Research. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

James, M. (1980) On the receiving end: pupils’ perceptions of learning sociology and social studies at 16. The Social Studies Teacher, 10(2), 61–8.

James, M. (1987) Outcome evaluation, process evaluation and the experience of the dental health study. In Campbell, G. (ed.) Health Education, Youth and Community: A Review of Research and Developments. Lewes: Falmer.

Lang, P. (1983) How pupils see it. Pastoral Care in Education, 1(3), 164–75.

Lang, P. (1985) Taking the customer into account. In Lang, P. and Marland, M. (eds) New Directions in Pastoral Care. Oxford: Blackwell.

Lewin, K. (1948) Resolving Social Conflicts. New York: Harper.

McCormick, R. and James, M. (1983; 2nd edn 1988) Curriculum Evaluation in Schools. London: Croom Helm and Routledge.

McKernan, J. (1991) Curriculum Action Research: A Handbook of Methods and Resources for the Reflective Practitioner. London: Kogan Page.

National Curriculum Council (1990) Curriculum Guidance 5: Health Education. York: NCC.

Nixon, J. (ed.) (1981) A Teacher’s Guide to Action Research: Evaluation Enquiry and Development in the Classroom. London: Grant McIntyre.

Oja, S. and Smulyan, L. (1989) Collaborative Action Research: A Developmental Approach. Lewes: Falmer.

Parlett, M. and Hamilton, D. (1972) Evaluation as illumination: a new approach to the study of innovatory programmes, Occasional Paper 9. Edinburgh: Centre for Research in the Educational Sciences, University of Edinburgh. Reprinted in Hamilton et al. (1977).

Pring, R. (1985) Personal development. In Lang, P. and Marland, M. (eds) New Directions in Pastoral Care. Oxford: Blackwell, in association with NAPCE and ESRC.

Rudduck, J. (1990) Innovation and Change: Developing Understanding and Involvement. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Rudduck, J. and Hopkins, D. (eds) (1985) Research as a Basis for Teaching. London: Heinemann.

Simpson, M. (1990) Why criterion referenced assessment will not improve children’s learning. Curriculum Journal, 1(2), 171–83.

Stake, R. E. (1967) The countenance of educational evaluation. Teachers College Record, 68(7), 523–40.

Stenhouse, L. (1975) An Introduction to Curriculum Research and Development. London: Heinemann.

TGAT (1988) Task Group on Assessment and Testing: A Report. London: DES.

Thomas, W. (1928) The Child in America. New York: Knopf.

Thorp, J. (1982) Evaluating practice: pupils’ views of transfer from the primary to the secondary school. Pastoral Care in Education, 1(1), 45–52.

Tones, K. (1987) Health promotion, affective education and the personal-social development of young people. In David, K. and Williams, R. (eds) Health Education in Schools, 2nd edn. London: Harper & Row.

W alker, R. (1985) Doing Research: A Handbook for Teachers. London: Methuen.

Walker, R. and Adelman, C. (1975) A Guide to Classroom Observation. London: Methuen.

Williams, C. (1992) Curriculum relevance for street children. Curriculum Journal, 3(3), 277–90.