Chapter 7

Assessment, Learning and the Involvement of Students

Edited version of James, M. (1998) ‘Chapter 9: Assessment, learning and the involvement of students’. In Using Assessment for School Improvement (Oxford: Heinemann): 171–189.

Assessment of learning or assessment for learning?

Any assessment is only as good as the action that arises from it. This is what is meant by ‘consequential validity’. In other words, measurement for its own sake has no value; it is the inferences that are drawn from it and the actions that are taken on the basis of these inferences that determine the value of assessments. Since the purpose of schools is the education of children, assessments have little value unless they contribute to that purpose. They should help students to learn better and, in so doing, raise their achievements and contribute to school improvement. Assessment results alone cannot do this because, as the saying goes, you cannot fatten the pig simply by weighing it. Something has to be done with assessment data. Assessment of learning is therefore insufficient for educational purposes; assessment for learning is necessary.

This idea – that assessment can be built into teaching to enhance learning – is at the heart of the concept of formative assessment. Some people prefer to call this simply ‘educational assessment’. In this chapter I unpack this idea further and look in more detail at the implications for teachers’ practice.

Formative assessment

Formative assessment is usually taken to refer to the process of identifying what students have, or have not, achieved in order to plan the next steps in teaching. It will usually involve the diagnosis of learning difficulties, although this is not synonymous with standardised, psychometric, diagnostic assessments. Within formative assessment, the term ‘diagnosis’ usually possesses a more colloquial and less technical meaning.

Formative assessment is also distinguished from other forms of assessment in that it is, by definition, carried out by teachers. This is important if it is to inform the decisions teachers make in the classroom. The aspiration is that assessment should become fully integrated with teaching and learning and therefore part of the educational process rather than a ‘bolt-on’ activity.

In an important article published in 1989, Royee Sadler, an Australian writer, outlines a theory of formative assessment.1 In this he explains the nature of the relationship between formative assessment and teaching. He considers that feedback is the key element in formative assessment and he sees two audiences for this: the teacher and the student. Feedback to the student, mediated by the teacher, is particularly important because no learning can take place without the active involvement of the student. According to Sadler:

The indispensable conditions for improvement are that the student comes to hold a concept of quality roughly similar to that held by the teacher, is able to monitor continuously the quality of what is being produced during the act of production itself, and has a repertoire of alternative moves or strategies from which to draw at any given point. In other words, students have to be able to judge the quality of what they are producing and be able to regulate what they are doing during the doing of it. (. . .)

Stated explicitly, therefore, the learner has to (a) possess a concept of the standard (or goal, or reference level) being aimed for, (b) compare the actual (or current) level of performance with the standard, and (c) engage in appropriate action which leads to some closure of the gap.

Sadler writes about ‘standards’ rather than ‘criteria’ in order to distance himself from the sophisticated technical approaches that have grown up around criterion-referenced assessment. His interest is in the kind of qualitative judgements that competent teachers make using multiple criteria to appraise the work of students over a series of assessment tasks. For him, it is the configuration or pattern of performance that takes precedence. This is particularly relevant to the British context because it is the kind of judgement that teachers are expected to make in teacher assessment using ‘level descriptions’.

Students monitoring themselves

Sadler says that such qualitative judgements can be made dependable by the development of natural-language descriptions and by exemplar material to which both teachers and students should have access. He wants the goal of formative assessment to move eventually from a system of teachers giving students feedback to one in which students monitor themselves. This requires the development of an evaluative language, shared by teachers and students, based on the development of meta-cognitive skills, i.e. the skills that enable the kind of reflection on performance that Sadler mentions in the quotation above.

Sadler argues that such skills can be developed by providing ‘direct authentic evaluative experience’ for students. He suggests that the provision of examples of students’ work which have been assessed, preferably with commentary on the features used in making the judgement, has an important role to play in this. In other words, not only can examplar material help teachers to gain an understanding of standards in a given area, but it can fulfil the same role for students. Conversely, he is sceptical of the usefulness of grades or scores for communicating anything of formative value.

In any area of the curriculum where a grade or score assigned by a teacher constitutes a one-way cipher for students, attention is diverted away from fundamental judgements and the criteria for making them. A grade therefore may actually be counterproductive for formative purposes.

The involvement of students in assessment

The description of formative assessment given above indicates that student self-assessment and peer-assessment should not be regarded as an optional extra but should be an essential part of any assessment that aspires to have a positive impact on learning. However, the kind of self-assessment implied is far removed from the practice of simply allowing students to ‘mark’ their own work using the teacher’s grading scheme. When students do the latter they often simply mimic what they have seen teachers do without any real understanding.

In order to make self- assessment effective, students have to be ‘let into the secrets’ of teachers’ professional practice so that they acquire some of their skills and understandings. This is a major task because students can be a very conservative influence and may be resistant to taking over any part of what they see as ‘the teacher’s job’. Moreover, it assumes that teachers have a firm grasp of the principles of formative assessment, which is not always the case.

When I recall my own experience as a school teacher. I am embarrassed when I think of the times that I introduced a lesson with such words as, ‘Today we are going to look at a poem by Ted Hughes’. I would set some homework based on questions about the poem, and I would mark the work produced. I might have said something about the quality of students’ work when I handed it back and I might have indicated what I was looking for, but it did not always occur to me to build this kind of discussion deliberately into the lesson before I set the task. I was teaching Ted Hughes rather than teaching students how to learn. Many things have changed since I was a schoolteacher, but I still hear teachers worrying about ‘getting through the syllabus’ when they should perhaps be more focused on what students actually learn.

In what ways should students take part?

So what involvement should students have in the assessment process if it is to be formative for learning? The following are indicated by research.

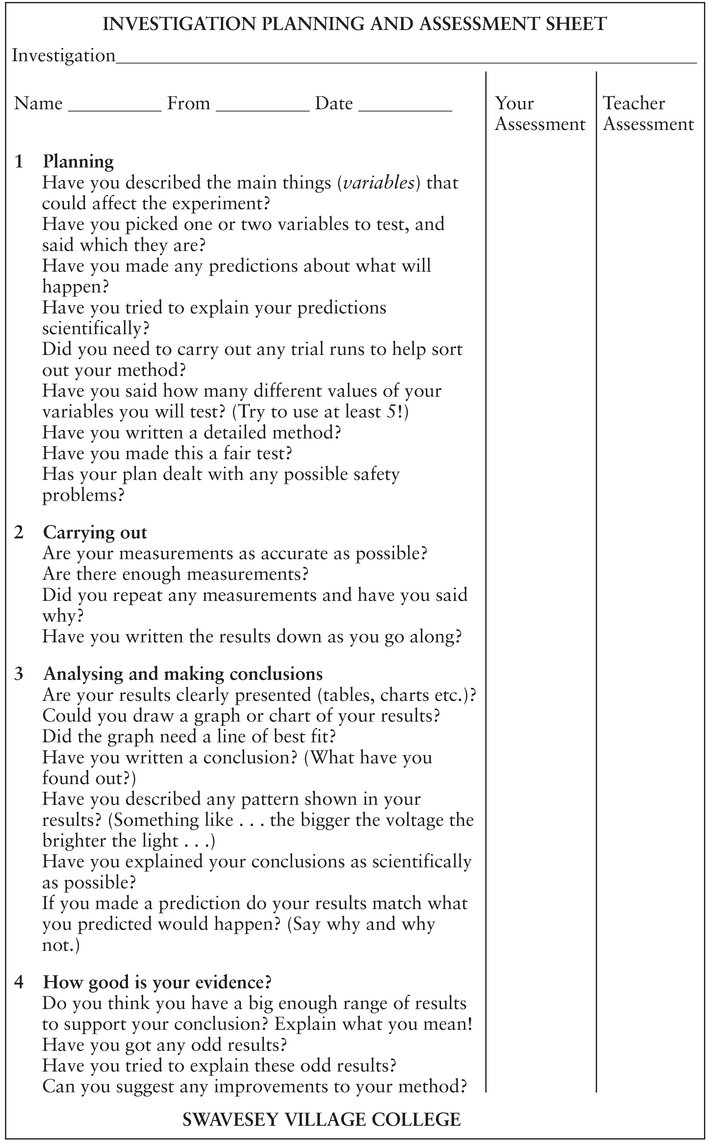

- Access to criteria Students should have an understanding of what would be regarded as mastery or desired performance in an area of learning. This means that teachers need to discuss the criteria and standards for assessment with them. If existing ‘official’ criteria are couched in teacher language then it is worth spending some time translating these, with students, into a form that they can more easily comprehend. This is possible, even with students with learning difficulties. While I was involved with the national evaluation of records of achievement pilot schemes in the 1980s, I observed a teacher in a special school work with his class to produce a set of criteria for science, based on published criteria for teachers. These were made into a poster and pinned to the classroom wall. When students thought they had achieved one of the criteria they asked their teacher to come and discuss the evidence with them prior to recording the achievement. A similar set of criteria are given in Table 7.1. These are from the science department of a Cambridgeshire Village College and relate to National Curriculum Science Attainment Target 1.

- Access to assessed examples Criteria and standards are often phrased in generalised ways, so it is also important that students have access to examples of assessed work so that they can see what the standards look like in practice. This argues for the use of exemplification material with students, for learning purposes, as well as with other teachers for establishing consistency in marking. This should not impose an additional burden on teachers if they have already created a portfolio of exemplars. Exemplars do not always have to provide ‘model answers’; a great deal can be learned from evidence of shortcomings and mistakes. Indeed, some of the Key Stage 3 national tests in mathematics have attempted to be formative by asking students to analyse mistakes in the computations of others, rather than simply asking students to do computations themselves.

- Opportunities to set their own tasks It is usually assumed that assessment tasks will be designed and set by the teacher. However, if students understand the criteria for assessment in a particular area, they are likely to benefit from the opportunity to design their own tasks. Their motivation will be increased and thinking through what kind of activity would meet the criteria and standards will, itself, contribute to learning. Within GCSE coursework and GNVQ there is some opportunity for students to choose their own projects. The important thing to consider, however, is not only the choice of theme but also what will meet the assessment criteria.

Self- assessment and peer assessment If students are to learn from their own performance in order to improve, they need to be able to assess and evaluate their actual performance against standards. They need to identify any gaps between actual and desired levels and they need to be able to work out why these gaps have occurred. Then, they need to identify the strategies that they might use to close the gap and meet the standard on another occasion. This is a complex activity but it has to be done by the students because it is they who are the learners and they need to internalise the process. Learning cannot be done for them by the teachers.

Teachers have an important role, however, in teaching students the meta-cognitive skills to carry out this process. They can do this by working through examples with individuals or groups and making clear to them the thinking processes that they go through, and which they want students to acquire. Students can then be given examples to work on themselves (their own or those from other people) in much the same way that they might be given tasks in the subject field. Teachers might protest that this addition to their professional role takes time from teaching their subject, and they have little enough time as it is. My response would be that spending some time on developing students’ meta-cognitive skills is likely to have very positive outcomes in terms of raising students’ achievements.

Perhaps the most crucial aspect of training students in self-assessment and peer assessment is enhancing the quality of the discourse. Most students are imbued with a culture that values the ability to give ‘correct’ answers quickly through rapid recall of stored information. What is needed for self-assessment is quite different. Students need to be trained to ask thoughtful questions of their own work and that of their peers; they need to be helped to admit problems without risking the loss of self-esteem; they need to take time to puzzle over the reasons why problems have arisen; and they need know that it is acceptable to look at a number of possible solutions before opting for a particular course of action.

Dialogue with someone else can be very valuable to raise awareness of hidden possibilities or challenge taken-for-granted assumptions. The teacher can be one partner in this, and should be on some occasions, but given the numbers in the average class this is not always practicable. Peers can often take this role and, by acting as a critical friend to a fellow student, they will almost inevitably enhance their own understandings as well.

Opportunities to implement strategies for improvement If students have identified areas for improvement and decided strategies for achieving better outcomes, they need opportunities for putting strategies into practice. This argues for self-assessment to be integrated into an interim stage in the completion of assessment tasks (perhaps at final draft stage and earlier). Otherwise it may be some time before students have opportunities to improve their performance on a particular set of criteria in a particular area of the curriculum.

The process of formative assessment involving students in the way described here may require learning to be slowed down so that it can be deeper, more thoughtful, and more secure. Time will also be needed to induct students into the processes and understandings associated with good assessment practice. So be it. In my view, there is little to be gained by racing through the syllabus and achieving only partial, superficial or surface learning. Such an approach, however, may require teachers to strip away some of the detail in their schemes of work in order to concentrate only on key learning objectives and essential knowledge and understandings.

Table 7.1 Student-friendly science criteria

The arguments for student self-assessment

All these suggestions may constitute a fairly radical departure from existing practice for many teachers and change will need to be supported by senior managers and an appropriate staff development programme. Teachers will also need to be convinced that it is likely to be worth taking the risks associated with innovation. Some very compelling evidence that such an approach will actually work, and have substantial benefits, can be found in the review of research carried out by Paul Black and Dylan Wiliam and reported in ‘Assessment and classroom learning’, Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice Vol. 5. Issue 1, 1998: 5–75.

A study in Portugal, reported by Fontana and Fernandes in 19942, involved 25 mathematics teachers taking an INSET course to study methods for teaching their pupils to assess themselves. During the 20 week part-time course, the teachers put the ideas into practice with a total of 354 students aged 8–14. These students were given a mathematics tests at the beginning and end of the course so that their gains could be measured. The same tests were taken by a control group of students whose mathematics teachers were also taking a 20 week part- time INSET course but this course was not focused on self-assessment methods. Both groups spent the same time in class on mathematics and covered similar topics. Both groups showed significant gains over the period but the self- assessment group’s average gain was about twice that of the control group. In the self- assessment group, the focus was on regular self-assessment, often on a daily basis. This involved teaching students to understand both the learning objectives and the assessment criteria, giving them an opportunity to choose learning tasks, and using tasks that gave scope for students to assess their own learning outcomes.

Other studies in Black and Wiliam’s review report similar achievement gains for students who have an understanding of, and involvement in, the assessment process. Moreover, there is strong evidence that the gains for customarily ‘low attainers’ are higher than for ‘high attainers’, although these latter also make gains. In other words, the long tail of underachievement (an especially worrying feature of British education for many years) is reduced in these studies. If implemented nationwide, strategies to promote formative assessment, incorporating student self-assessment have the potential to raise standards generally and the achievements of ‘low attainers’ in particular.

Those schools and teachers who were involved in the records of achievements movement in the 1980s will probably say that this is what they were arguing for all along, believing that the process was central for motivation and improved learning. The artefact called a ‘Record of Achievement’ was in some senses always of secondary importance.

This argument was never really understood by government, however, and the National Record of Achievement fell short of its promise. The relaunch of the NRA as a ‘formative’ document will need to take on these ideas about processes if it is not to go the same way. However, in contrast to the record of achievement pilot schemes in the 1980s, we now have, in Black and Wiliam’s review, a strong empirical base for arguing for the efficacy of formative self-assessment for improving students’ learning. Carpe diem: we should seize the day.

Formative assessment and theories of learning

In arguing that processes of formative assessment contribute to improved student learning, I have largely drawn on theoretical accounts, such as Royce Sadler’s, and empirical evidence, such as that collected by Black and Wiliam. In order to convince teachers and help them in their practice, it may also be important to explain how assessment interacts with learning and why it is so important. Any formulation of formative assessment really needs to be grounded in both empirical evidence and learning theory. I realise that theory became unfashionable, even despised in certain quarters, during the 1990s, but we all have at least informal theories about how the world works. If we did not, we could not act, except instinctively. According to Kurt Lewin, ‘There is nothing so practical as a good theory’; there are a number of good, if competing theories, about how learning takes place and the role of assessment in this process.

Two different theoretical perspectives appear to underlie most approaches to formative assessment although they often involve superficially similar practices and procedures, such as the specification of criteria for achievement within a domain. These two main perspectives are derived from behaviourist theoretical positions or constructivist theoretical positions.

Formative assessment from a behaviourist perspective

Formative assessment within a behaviourist tradition emphasises the clear specification of performance criteria and the kind of evidence needed to demonstrate performance. Assessment is therefore integrated with teaching and learning in that:

- specific, achievable, and often short-term goals are set;

- appropriate curricular experiences are provided;

- tasks or tests are constructed in which performance can be assessed;

- assessments are made against performance objectives;

- feedback is provided to students on whether they have achieved the targets, which gives them information about what is expected next time.

This kind of approach has underpinned much work in the graded assessment field and is the acknowledged foundation in vocational assessment, especially National Vocational Qualifications. A case can also be made for saying that this was the basis of SEAC and SCAA’s interpretation of the formative role of teacher assessment in National Curriculum assessment during the period when assessment was focused on statements of attainment (1990–95).

In memorising facts and learning skills it is indeed useful to find out what facts or skills have been acquired. The feedback it provides to help further learning is in terms of what has not been learned and what should be tried next time. The action to be taken usually involves further practice and reward or praise when the goal has been achieved. In this context a behaviourist approach may be quite acceptable with its notions of stimulus, response and reinforcement.

Learning and assessment of ball-control skills in PE provides an example. Whilst it may be helpful to understand something of the physics of motion, a student’s ability to control the speed and direction of a ball will largely depend on practising certain techniques. When the ball fails to reach its target, the student may be able to say what went wrong but, if not, an observer can provide feedback and suggest what to do next time. If the next shot reaches its goal, this will be reward in itself, but if the goal is not so obvious a word of praise will indicate to the learner that the movement was correct and should be repeated on another occasion. In this context, praise rarely gets in the way of learning because it will reinforce a correct sequence of movements. However, when understanding or deep learning is involved, praise may be counter-productive.

Formative assessment from a constructivist perspective

From a constructivist perspective, formative assessment is viewed rather differently. It focuses not so much on behaviour as on cognition (thought), generated in a social context3. In particular it is interested in promoting learning with understanding, which is actively understood and internalised by the learner.

Contemporary cognitive psychology supports the notion that understanding involves creating links in the mind and that making sense of something depends on these links. Isolated pieces of information do not have links to existing mental frameworks and so are not easily retained. The identification and creation of links to existing frameworks depends on the active participation of the learner and on the familiarity of the context of the material to be learned.

Understanding, in this view, is the process of construction and reconstruction of knowledge by the learner. What is known and understood will, of course, change with new experience and as new ideas and skills are presented to help make sense of it. Thus the characteristics of this learning are that it:

- is progressively developed in terms of big ideas, skills for living and learning, attitudes and values;

- is constructed on the basis of previous ideas and skills;

- can be applied in contexts other than those in which it was learned;

- is owned by the learner in the sense that it becomes a fundamental part of the way he or she understands the world; it is not simply ephemeral knowledge that may be memorised for recall in examinations but subsequently forgotten.

Relating new knowledge to existing understandings

Constructivists therefore argue that an assessment system intended to improve the quality of learning should not treat students as imperfect learners, but as people who are actively trying to make sense of what they are taught. For this reason, it is important that teachers should try to discover how students have related new knowledge to their existing understandings, and, more importantly for self-assessment, students should learn to do this for themselves.

Many teachers will be familiar with the practice of ‘concept-mapping’ and this is similar to what I have in mind. Teachers and peers can only do this by observing student learning and asking students to ‘think aloud’ about what they have learned and understood. The information gained allows teachers and students, in dialogue, to analyse misunderstandings or the extent to which previous experiences, attitudes and values, or expectations, have influenced learning. On this basis, appropriate next steps in both teaching and learning can be planned.

Drawing on a similar analogy to that of archery, Mary Simpson, a constructivist researcher from Scotland, argues4:

Assessment must therefore extend beyond the simple determination of the extent to which [students] have learned as intended to the discovery of what they have actually learned, right or wrong. Teachers, like marksmen, may have clear objectives, but if they are to improve the quality of their performance then – like marksmen – they will want to know where all their shots went, and not merely how many find their target. Indeed, the patterns of ‘wrong’ learning, like the distribution of off- target shots, will provide the clearest cues to improvement.

Later in the same article she makes another important point:

But pupils do not learn only what they have been taught, only within school, or only from their teachers. Any system of assessment which is to make a positive contribution to pupil learning must be one which allows pupils’ actual knowledge structures within specific topic domains to be adequately mapped. Since this involves pupils in volunteering information about their uncertainties, it can only be carried out in a setting which allows that information to be confidential between pupils and teacher and in which the latter is not a judge or even an accessory to the judging process, but a participant in an informal contract with pupils to share the responsibility for learning.

Since students often bring different experiences, attitudes and structures of knowledge to any task, particular attention needs to be paid to the construction of the assessment tasks themselves. There is little justification for assuming that the task will be interpreted precisely as the task- setter intended because there will be no one-to-one correspondence between the contents of any two peoples’ minds. Given this, teachers are probably in a better position than many external test developers to construct appropriate assessment tasks for their students and to interpret the results. They are in a good position to question and find out how students’ previous experiences frame their thinking and therefore what will stimulate students to reveal their knowledge and understandings. This also supports the idea that students themselves should have a role in task design and choice.

Of course, a great deal of time is required for this kind of effort. The pressures imposed by the National Curriculum, even in its reduced post-Dearing form, allow little space or resources for truly reflective practice or the professional development needed to support reflective teaching. Hopefully, as things settle down and provided that no major new ‘reform’ is introduced, teachers may be able to develop their practice incrementally along these lines.

Assessment for learning in the twenty-first century

Teaching pupils to become good learners will be a key role for teachers as the information revolution and the restructuring of employment continues to have an impact on people’s lives and on the relevance of traditional knowledge and skills. In this context, it is unlikely that simply learning quantities of information or acquiring practical skills will be adequate to deal with rapid change.

Whilst numeracy, literacy and IT skills (the so-called ‘key-skills’) will continue to be a foundation, learning beyond the basics will require a considerable measure of conceptual understanding, and intrapersonal and inter-personal skills and understandings of a similarly high order. Without this ‘learning with understanding’, young people are unlikely to possess the strategic vision, self-motivation, problem-solving capacity, flexibility and adaptability that will be required for ‘lifelong learning’ in the ‘learning society’ of the twenty-first century. Therefore, the second kind of formative assessment described here, grounded in a constructivist theory of learning, will need to become part of the professional practice of most teachers.

Distinguishing formative from summative assessment5

Summative assessment has a quite different purpose, which is to describe learning achieved at a certain time for the purposes of reporting to parents, other teachers, the students themselves and, in summary form, to other interested parties such as school governors. It has an important role in monitoring the overall educational progress of students but not in day-to-day teaching, as does formative assessment.

Unlike summative assessments, which may be either criterion-referenced or norm-referenced, formative assessments are always made in relation to where students are in their learning in terms of specific content or skills. To this extent, formative assessment is, by definition, criterion-referenced. At the same time, it must also be student-referenced or ipsative. This means that a judgement of a student’s work or progress takes into account such things as the effort put in, the particular context of the student’s work and the progress that the student has made over time. In consequence the judgement of a piece of work, and what is fed back to the student, will depend on the student and not just on the relevant criteria.

The justification for this is that the individual circumstances must be taken into account if the assessment is to help learning and to encourage the learner. If formative assessment were purely criterion-referenced it would be profoundly discouraging for many students who are constantly being faced with failure. This hybrid of criterion-referenced and student-referenced assessment is acceptable as long as this information is used diagnostically in relation to each student, which is consistent with the notion that formative assessment is essentially part of teaching.

The claim that criterion-referenced systems often only thinly disguise norm-referenced systems would lead to the contentious notion that there is some degree of norm-referencing in formative assessment. It is true that any attempt to articulate a trajectory of development of knowledge, skill and understanding in any subject domain often implies assumptions about ‘normal’ stages of development and progression. Also, judgements about an individual’s progress in relationship to others is sometimes helpful in identifying whether there is an obvious problem that needs to be tackled urgently. This is probably a main reason why parents continue to be so concerned about where their child is in relation to the attainments of others of the same age.

The point to be made here in the context of formative assessment, however, is that whilst norm-referenced assessment might help teachers recognise the existence of a problem, it can offer them no help in knowing what to do about it and may simply have a deleterious effect by labelling students. In order to contribute to learning through teaching, assessments need to reveal the specific nature of any problems; this can only be achieved by a combination of criterion- and student-referenced assessments.

Using evidence appropriately to improve performance

It is important to recognise that the reality of formative assessment is that it is bound to be incomplete, since even the best plans for observing activities or setting certain tasks can be torpedoed by unanticipated events. Moreover, the information will often seem contradictory. Students are always changing and may appear to be able to do something in one situation but not in another. Such evidence is a problem where the purpose is to make a judgement about whether a student fits one category, criterion, or one level or another. However, where the purpose is to inform teaching and help learning, the fact that a pupil can do something in one context but apparently not in another is a positive advantage, since it gives clues to the conditions which seem to favour better performance and thus can be a basis for taking action.

In this way the validity and usefulness of formative assessment is demonstrated and enhanced. Validity is vitally important to formative assessment because it cannot claim to be formative unless it demonstrably leads to action for improved learning – the point that I made at the beginning of this chapter.

However, it is not necessary to be over-concerned with reliability in formative assessment since the information is used to inform teaching in the situations in which it is gathered. Thus there is always quick feedback for the teacher who usually has opportunities to use observations of the response to one intervention as information in making the next one. Through this rapid loop of feedback and adjustment between teacher and learner, the information inevitably acquires greater reliability. This is not to say that teachers do not need any help with this important part of their work, but the help required is to be found in how to identify significant aspects of students’ work and to recognise what they mean for promoting progress.

In summary, formative assessment can be distinguished from summative assessment because:

- it is essentially positive in intent, in that it is directed towards promoting learning; it is therefore part of teaching;

- it takes into account the progress of each individual, the effort put in and other aspects of learning which may be unspecified in the curriculum; in other words, it is not purely criterion-referenced;

- it has to take into account several instances in which certain skills and ideas are used and there will be inconsistencies as well as patterns in behaviour; such inconsistencies would be 'error' in summative evaluation, but in formative evaluation they provide diagnostic information;

- validity and usefulness are paramount in formative assessment and should take precedent over concerns for reliability;

- even more than assessment for other purposes, formative assessment requires that pupils have a central part in it; pupils have to be active in their own learning (teachers cannot learn for them) and unless they come to understand their strengths and weaknesses, and how they might deal with them, they will not make progress.

In contrast, the characteristics of summative assessment are that:

- it takes place at certain intervals when achievement has to be reported;

- it relates to progression in learning against public criteria;

- the results for different pupils may be combined for various purposes because they are based on the same criteria;

- it requires methods which are as reliable as possible without endangering validity;

- it involves some quality assurance procedures;

- it should be based on evidence from the full range of performance relevant to the criteria being used.

Linking formative and summative assessment

It would be wrong to suggest that information gathered by teachers for formative purposes should not be used when they come to make summative assessments. This would be wasteful and, in any case, impossible in practice, because teachers cannot ignore knowledge that they have of students. Instead it is essential to distinguish different ways of arriving at an assessment judgement for different purposes.

At this point it is useful to keep in mind that the kind of information that is gathered by teachers in the course of teaching is not tidy, complete and self-consistent, but fragmentary and often contradictory. The unevenness, as mentioned above, is not a problem but an advantage for formative purposes, helping to indicate what supports or hinders achievement for a particular pupil. However, these uneven peaks and troughs have to be smoothed out in reporting performance for summative purposes. Thus although some of the same evidence can be used for formative and summative purposes, for the latter it has to be reviewed and aligned with criteria applied uniformly across all pupils. This means looking across the range of work of a pupil and judging the extent to which the profile as a whole matches the criteria in an holistic way.

The alternative to using the same results of assessment for both purposes is, therefore, to use relevant evidence gathered as part of teaching for formative purposes but to review it, for summative purposes, in relation to the criteria which will be used for all pupils. This means that formative assessment can remain a mixture of criterion-referenced and student- referenced assessment, as is required for providing a positive response to students and encouraging their learning. At the same time the use of information gathered as part of teaching, appropriate for formative assessment but which could be misleading or even confusing if used directly for summative assessment, is filtered out in the process of reviewing information relevant to the criteria being applied, in the National Curriculum level descriptions, for example. In other words, summative assessment should mean summing up the evidence, not summing and averaging across a series of assessment judgements that have already been reduced to letter or numerical grades. Similarly, formative assessments should not be recorded in the form of mini-summative judgements; rather there should be records of work completed with observations and notes of how these have been used to help progress.

Using evidence to maximise value: an illustration

If opportunities to distinguish between the formative and summative use of the evidence are missed, the formative value of information about students’ learning can be neglected. For example, one element of the ‘Exemplification of Standards’ material, distributed to all schools in England and Wales in 1995 by the Schools Curriculum and Assessment Authority (SCAA) and the Advisory Council on Assessment and the Curriculum for Wales (ACAC), was a video and booklet containing evidence of pupils engaged in speaking and listening (English Attainment Target 1) and judged to be at various levels from 1 to 8. The Key Stage 3 material includes footage of a girl named Nicole, for whom English is ‘an additional language’, who is seen contributing to four different activities.

A teacher viewing this video might notice that Nicole watches the faces of peers very closely, although sometimes obliquely, and sometimes angles herself so that she can read the text from which they are reading. She is often to the side of group interaction and has difficulty breaking into a fast verbal exchange. Occasionally her contributions are ‘talked over’ by others who are more forceful. However, when the activity gives her an opportunity to ‘have the floor’, she speaks quietly and slowly but more confidently and her contributions are structured and comprehensible.

This kind of evidence might be used formatively by the teacher to indicate how Nicole’s learning in this area might be extended by building on her listening skills; by acknowledging the tremendous progress she has made in competent use of her second language; by helping her with sentence constructions that she finds especially difficult; by providing her with more opportunities to speak in formal presentations where she cannot be interrupted by more confident peers; and by working with the whole group on their understanding of the nature and dynamics of group discussion to allow better pacing; turn taking, listening, inclusion etc.

None of this is mentioned in the material accompanying the video because it is ‘designed to help teachers make consistent judgements about which level best describes a pupil’s performance’. Thus the commentaries on Nicole’s contributions relate strictly to the general criteria embedded in the level descriptions. The peaks and troughs and idiosyncrasies of her performance are ironed out for the purpose of coming to the following summary and overall judgement:

Although she perhaps lacks confidence, Nicole contributes clearly and positively in discussions. She makes substantive points, gives reasons and is able to argue for her views when challenged. She is beginning to ask questions of others and take account of their views. She adjusts her speaking to more formal situations although she is not fully confident in standard English. Overall, Nicole’s performance is best described by Level 5.

Many other examples similar to this last one indicate that the fundamental distinction between formative and summative assessment has not been fully articulated. Formative and summative assessment may relate to each other in that they share a set of common criteria which are agreed expectations in terms of desired outcomes, but beyond this they are essentially different phenomena with different purposes, different assumptions and different methods. Some of the same evidence may be used for the different purposes but it will be used in different ways.

Developing this new approach

It is essential to provide help for teachers with both formative and summative assessment and in a way which disentangles the two and enables teachers to use assessment in a genuinely formative way to help students’ learning. This would include guidance on types of feedback from teachers necessary to maintain pupil motivation as well as on identifying specific aspects of attainment or good performance and what to do to help further improvement. For formative assessment, teachers may need assistance in identifying ‘next steps’ in learning, perhaps more in relation to some subjects, such as science, than in others.

The further development of exemplar materials may be important here, but only if the materials are directed towards the need to make ‘next steps’ decisions, as well as the need to make overall summative judgements. Teachers may also value examples of techniques for gaining access to students’ ideas and for involving the latter in self-assessment and in deciding their ‘next steps’. There is now considerable evidence that such collaboration between teacher and students facilitates learning in a very direct and positive way.

Notes

1 Sadler, D. Royce (1989) ‘Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems’, Instructional Science, 18, pp. 119–44.

This is not an easy article but it has been very influential and is often referred to.

2 Fontana, D. and Fernandes, M. (1994) ‘Improvements in mathematics performance as a consequence of self-assessment in Portuguese primary school children’, British Journal of Educational Psychology, 64, pp. 407–417.

3 Constructivism has several variants. The most recent emphasise that the structures of thinking are generated in interactive processes between people in specific contexts of action. These versions are called social constructivism, situated cognition or socio-cultural approaches.

4 Simpson, M. (1990) ‘Why criterion-referenced assessment is unlikely to improve learning’, The Curriculum Journal, 1(2), pp. 171–83.

5 The remaining sections of this chapter are an edited version of an article by Wynne Harlen and myself entitled ‘Assessment and Learning: differences and relationships between formative and summative assessment’, published in Assessment in Education, 4(3), 1997, pp. 365–79.

I am very grateful to Wynne Harlen for allowing me to reproduce some of her words in this text.