A. History of the Internet and the World Wide Web

B. Characteristics of the World Wide Web

5. Electronic Mass Media Online

D. Television’s Migration to the Web

D. The World Wide Web and the Mass Media

Although many people believe that the Internet is a 1990s invention, it was actually envisioned in the early 1960s. Over the last 50 or so years, the Internet has gone from having the technological capability of sending one letter of the alphabet at a time from one computer to another to a vast system in which trillions of messages are sent around the world every day.

This chapter covers how the Internet works and discusses how the various Internet resources are used: the Web, email, YouTube, blogs, electronic mailing lists, newsgroups, chat rooms, instant messaging, social network sites, Twitter, and podcasting. Social media and blogs are also discussed in more detail and from a social perspective in Chapter 9. This chapter focuses primarily on the benefits and challenges of online information and how it affects traditional media, especially radio and television. An in-depth look at new content delivery systems, such as Spotify and Hulu, is included in Chapter 6. The Internet has improved the lives of many people but has caused problems for others. Understanding how a technology developed and made its way into everyday life is the first step to guiding where it is going.

See It Then

History of the Internet and the World Wide Web

In the early 1960s, scientists approached the U.S. government with a formal proposal for creating a decentralized communications network that could be used in the event of a nuclear attack. By 1970, ARPAnet (Advanced Research Projects Agency Network) was created to advance computer interconnections.

The interconnections established by ARPAnet soon caught the attention of other U.S. agencies, which saw the promise of using an electronic network for sharing information among research facilities and schools. While disco music was hitting the airwaves, Vinton Cerf, later known as ‘the father of the Internet,’ and researchers at Stanford University and UCLA were developing packet-switching technologies and transmission protocols that are the foundations of the Internet. In the 1980s, the National Science Foundation (NSF) designed a prototype network that became the basis for the Internet. At the same time, a group of scientists in the European Laboratory of Particle Physics (CERN) was developing a system for worldwide interconnectivity that was later dubbed the World Wide Web. Tim Berners-Lee headed the project and was dubbed ‘the father of the World Wide Web.’

Zoom In 5.1

See Tim Berners-Lee on YouTube talking about how the Internet was created:

Characteristics of the World Wide Web

For many years, the Internet was the domain of scientists and researchers. It came into widespread use only in 1993 with the advent of the easy-to-use World Wide Web. Since then, the Internet has become a tremendously important part of our daily media diet. Most online users have come to think of the Internet and the Web as synonymous, but the Web is the part of the Internet that brings graphics, sound, and video to the screen.

What Is the Internet?

Simply stated, the Internet is a worldwide network of computers. Millions of people around the globe upload and download information to and from the Internet every day. The Internet is a digital venue that connects users to each other and to vast amounts of information. Like radio and television, the Internet is a mass medium in the respect that it reaches a broad range of users.

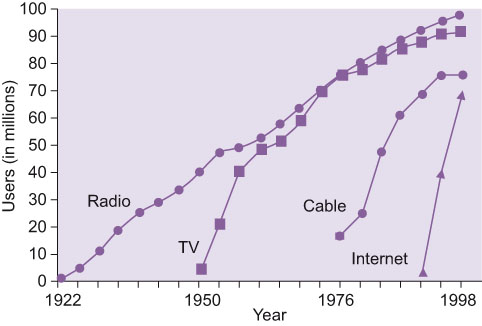

By definition, before any medium can be considered a mass medium, it needs to be adopted by a critical mass of users. In the modern world, about 50 million users seems to be the benchmark. The Internet became a mass medium at an unprecedented speed. Radio broadcasting (which began in an era with a smaller population base) took 38 years to reach the magic 50 million mark, and television took 13 years. The Internet surpassed 50 million regular U.S. users sometime in late 1997 or early 1998, only about 5 years after the World Wide Web made it user friendly.

Fig. 5.1 Media adoption rates

Source: Shane, 1999

The Internet is distinguished from other mass media, such as radio and television, by its inclusion of text, graphics, video, and sound into one unique medium. Whereas newspapers are print only, radio audio only, and television audio and video, these properties converge on the Internet. Convergence is generally defined as the “coming together of all forms of mediated communication in an electronic, digital form, driven by computers” (Pavlik, 1996, p. 132). Another researcher defined convergence as the “merging of communications and information capabilities over an integrated electronic network” (Dizard, 2000, p. 14).

FYI: The Word ‘Internet’

The word Internet is made up of the prefix inter, meaning ‘between or among each other,’ and the suffix net, short for network, which is ‘an interconnecting pattern or system.’ An inter-network, or internet (small i), refers to any ‘network of networks’ or ‘network of computers,’ whereas Internet with a capital I is the specific name of the computer network that provides the World Wide Web and other interactive components (Bonchek, 1997; Krol, 1995; Yahoo! Dictionary Online, 1997).

Technology

The World Wide Web is a technologically separate and unique medium, yet it shares many properties with traditional media. Both its similarities and differences have made it a formidable competitor for the traditional mass media audience.

When comparing traditional media, each can be distinguished by unique characteristics. Radio is convenient and portable and can be listened to even while the audience is engaged in other activities. Television is aural and visual and captivating; print (magazines, newspapers) is portable and can be read anytime, anywhere. The Web has some of these same advantages. For example, people can listen to online audio while attending to other activities, they can read archived information anytime they please, and they can sit back and be entertained by graphics and video displays. In addition, the Internet provides online versions of print media, which can be read electronically or even printed to provide a portable version. The New York Times at www.nytimes.com, Rolling Stone at www.rollingstone.com, and Elle Magazine at www.elle.com are just a few example of online versions of print media. The Internet also offers benefits not offered by traditional media: two-way communication through email, chat, and other interactive tools.

Although the Internet’s proponents highly tout this medium, it falls short of traditional media in some ways. Users must have access to a computer, smartphone, or other Wi-Fi-enabled device (such as a tablet) to access online material. Many cannot afford a computer or other device, and there are many places where it is inconvenient or just not possible to get an Internet connection. Unlike free over-the-air radio broadcasting, access to the Internet requires a subscription to an Internet service provider (ISP), such as Earthlink, a cable company like Comcast, a phone company like Verizon, or a public wired or wireless connection.

Content

The Web is unique because it displays information in ways similar to television, radio, and print media. Radio delivers audio, television delivers audio and video, and print delivers text and graphics. The Web delivers content in all of these forms, thus blurring the distinction among the media.

The Web’s big advantage over traditional media is its lack of space and time constraints. The length of radio and television content is limited by available airtime, and print is constrained by the available number of lines, columns, or pages. These limitations disappear online. News and entertainment on the Internet are not physically confined by seconds of time or column inches of space but are restricted only by editors or Web page designers.

Although the amount of content is largely unlimited, the speed of online delivery is constrained by bandwidth, which is the amount of data that can be sent all at once. Think of bandwidth as a water faucet or a pipe. The circumference of the faucet or pipe determines the amount of water that can flow through it and the speed at which it flows. Similarly, bandwidth determines the speed of information flow and thus affects how quickly content appears on the screen. Web designers might choose to reduce the amount of content to increase speed, for example. Bandwidth is becoming less of a concern, however, now that fast broadband connections are becoming commonplace.

How the Internet Works

The Internet operates as a packet-switched network. It takes bundles of data and breaks them up into small packets or chunks that travel through the network independently. Smaller bundles of data move more quickly and efficiently through the network than larger bundles. It is kind of like moving a home entertainment system from one apartment to another. The DVD player might be packed in the car and the large-screen television in the truck. The home entertainment system is still a complete unit, but when transporting, it is more convenient to move each part separately and then reassemble all of the components at the new place. The Internet works in almost the same way, except it disassembles bits of data rather than a home entertainment system and reassembles the bits into a whole unit at its destination point.

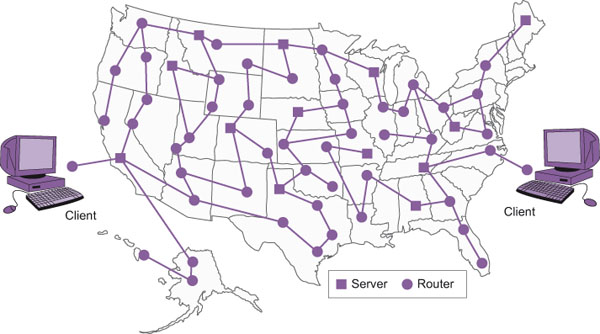

The bits of data that make up an email message, Web page, or image, flow through interconnected computers from their points of origin to the destination. The sender’s computer is the origination point, known as the client. The message bits leave the client computer and travel in separate packets to a server. A server is basically a powerful computer that provides continuous access to the Internet. From there, packets move through routers. A router is a computer that links smaller networks and sorts each packet of data until the entire message is reassembled, and then it transmits the electronic packets either to other routers or directly to the addressee’s server. The server holds the entire message until an individual directs his or her client computer to pick it up.

Servers and routers deliver online messages through a system called transmission control protocols/Internet protocols (TCP/IP), which define how computers electronically transfer information to each other on the Internet. TCP is the set of rules that governs how smaller packets are reassembled into an IP file until all of the data bits are together. Routers follow IP rules for reassembling data packets and data addressing so information gets to its final destination. Each computer has its own numerical IP address (which the user usually does not see) to which routers send the information. An IP address usually consists of between 8 and 12 numbers and may look something like 166.233.2.44.

Because IP addresses are rather cumbersome and difficult to remember, an alternate addressing system was devised. The Domain Name System (DNS) basically assigns a text-based name to a numerical IP address using the following structure: [email protected]. For example, in [email protected], the user name, MaryC, identifies the person who was issued Internet access. The @ literally means ‘at,’ and host.subdomain is the user’s location. In this example, anyUniv represents a fictitious university. The top-level domain (TLD), which is always the last element of an address, indicates the host’s type of organization. In this example, the top-level domain, edu, indicates that anyUniv is an educational institution.

Fig. 5.2 How the Internet works

Source: Kaye and Medoff, 2001

The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) assigns top-level domains. The first top-level domains created for the Internet were .com (commercial), .org (organization), .net (network), .int (international), .edu (education), .gov (government), and .mil (military). Over the years, other domain names were added such as .biz (business), .museum (museum), .coop (cooperatives), and .xxx (pornographic), and domains for countries and regions such as .ec (Ecuador), .it (Italy), .pl (Poland), .gb (Great Britain), and .eu (European Union). But the largest expansion came after 2013 when ICANN began accepting applications for custom domain names. By early 2015, there were just over 700 top-level domain names.

FYI: Top-Level Domains (2014)

Most Popular New Top-Level Domains added in 2014

| .today | (current events and issues) |

| .guru | (expert advice) |

| .solutions | (technical support) |

| .photography | (photography) |

| .tips | (sharing knowledge about any subject) |

| (email) | |

| .technology | (new technology) |

| .directory | (directory or lists) |

| .clothing | (retailers, boutiques, outlets, designers) |

| .solar | (solar power industry) |

Sources: Kerner, 2014; Skiffington, 2014

Prior to the creation of the Web, Internet content could be retrieved only through a series of complicated steps and commands. The process was difficult, time-consuming, and required an in-depth knowledge of Internet protocols. As such, the Internet was of limited use. In fact, it was largely unnoticed by the public until 1993 when undergraduate Marc Andreessen and a team of University of Illinois students developed Mosaic, the first Web browser. Different from the Internet in which data were retrieved by entering cumbersome commands, Mosaic was based on a system of clickable, intuitive hyperlinks. Mosaic caught the attention of Jim Clark, founder of Silicon Graphics, who lured Andreessen to California’s Silicon Valley to enhance and improve the browser. With Clark’s financial backing and Andreessen’s know-how, Netscape Navigator was born. This enhanced version of Mosaic made Andreessen one of the first new-technology, under-30-year-old millionaires. Once Netscape Navigator hit the market, the popularity of Mosaic plummeted. Since Mosaic and Netscape Navigator, other browsers, such as Netscape Communicator, have come and gone as new and improved ones, such as Firefox and Chrome, have taken their place.

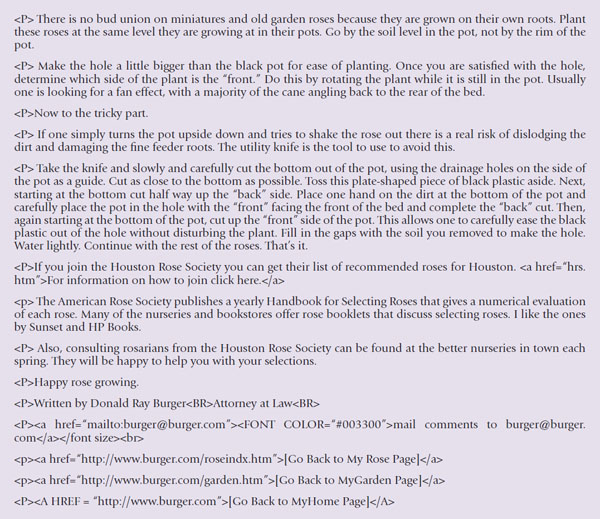

Electronic Mass Media Online

So far, this chapter has focused on the history of the Internet and on what the Internet is and how it works. As online technology improved, radio and television saw the potential for increasing their audience and revenue by delivering their content online. Stations and networks slowly developed online counterparts to their traditional over-the-air and cable-delivered content.

The Rise of Internet Radio

Almost all local radio stations have established a Web site, which typically provides news and community information, promotes artists and albums, and streams over-the-air programs and music. These Web sites lend credence to the media industry’s concern that Internet users may one day discover that they no longer need radios. Instead, they will just access radio programming over the Internet.

The rise of Internet radio somewhat mirrors the development of over-the-air radio. In the early days of radio, amateur (ham) operators used specialized crystal sets to transmit signals and voice to a limited number of listeners (usually other ham operators) who had receiving sets. Transmitting and receiving sets were difficult to operate, the reception was poor and full of static, and the sets themselves were large and cumbersome, leaving only a small audience of technologically advanced listeners who knew how to operate them. In the early days of radio, the technologically adept were the first to gravitate toward the new medium. In the 1990s, the technologically savvy again took the lead, but this time, they paved the way for cybercasting. In its early years, the Internet was accessed largely through a modem, which allowed digital signals to travel from computer to computer via telephone lines. Just as primitive radios and static-filled programs once kept the general public from experiencing the airwaves, bandwidth limitations and slow computer and modem speeds kept many radio fans from listening via the Internet. For example, using a 14.4-Kbps modem, Geek of the Week—a 15-minute audio-only program—took almost 2 hours to download, which was considered very fast in the mid-1990s.

Small- to medium-market radio stations and college stations generally led the way to the Internet. As their success stories quickly spread throughout the radio industry, other stations eagerly set up their own music sites. RealNetworks, the provider of RealAudio products, was the first application to bring real-time audio on demand over the Internet. Since the introduction of RealAudio in 1994, thousands of radio stations have made the leap from broadcast to online audiocast. By using RealAudio technology, AM and FM commercial radio, public radio, and college stations captured large audiences and moved from simply providing prerecorded audio clips to transmitting real-time audio in continuous streams. Streaming technology pushes data through the Internet in a continuous flow, so information is displayed on a computer before the entire file has finished downloading. Streamed audio and video selections can be played as they are being sent, so there is no waiting for the entire file to download.

Since RealAudio’s introduction, several other companies have developed audio-on-demand applications and new protocols for increasing bandwidth for even faster streaming. Online audio has come a long way since the early days of the Internet. Computer and Internet technology has become less expensive, easier to use, and able to deliver high-quality sound.

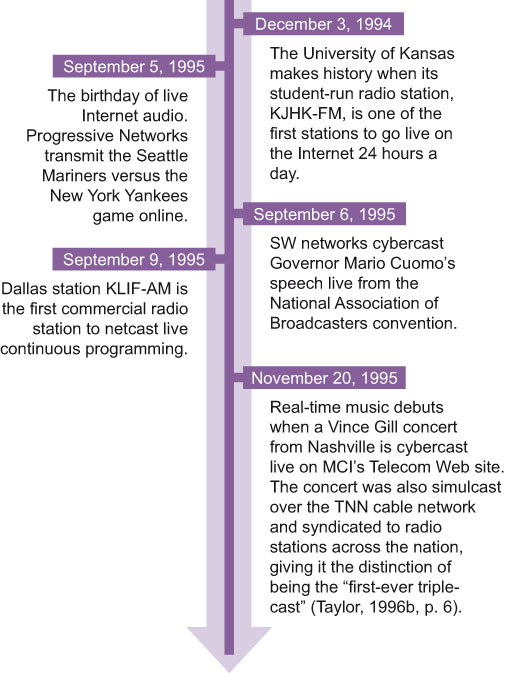

Fig. 5.3 Highlights of early Internet radio

In 1999, online music was transformed when college student Shawn Fanning created Napster, the first software for finding, downloading, and swapping MP3 (Moving Picture Experts Group, Audio Layer 3) music files online. Young adults’ love for music made the MP3 format and MP3 player the hottest trend since the transistor radio hit the shelves in the 1950s. At first, music file-sharing sites seemed like a good idea, but they quickly ran into all kinds of copyright problems and found themselves knee deep in lawsuits. Although it has always been legal for music owners to record their personal, store-bought CDs in another format or to a portable player, sharing copies with others who have not paid for the music is considered piracy and copyright infringement.

In the early 2000s, the recording industry launched a vigorous campaign against so called ‘music pirates,’ who shared or downloaded music files online for free. In 2003, RIAA (Recording Industry Association of America) sued 261 music lovers, targeting excessive pilferers. In some cases, the RIAA held individuals liable for millions of dollars in lost revenue, sometimes equaling up to $150,000 per song. After making its point, the RIAA worked out settlements in the $3,000 to $5,000 range and instituted the Clean Slate Amnesty program for those who wanted to avoid litigation by issuing a written promise to purge their computers of all files and never download music without paying again.

Napster was at the center of the illegal music download imbroglio. After building a clientele of about 80 million users but facing several years of legal wrangling, Napster went offline in July 2001. Napster made its comeback in late 2003, this time as a legal site. Napster has since merged with Rhapsody, a music streaming service with a monthly fee.

The question in the early 2000s was whether Internet users would pay for what they used to get for free. One study reported that only about one-quarter of Internet users who downloaded music in the past would be willing to pay to do so in the future, and another study claimed that only about one-third of college students would pay more than $8.50 per month to download music. Yet another report found that people who download free music do so to sample it, and if they like it, they’ll buy it. But now paying for downloading music has become commonplace and, for many, preferable to buying a CD.

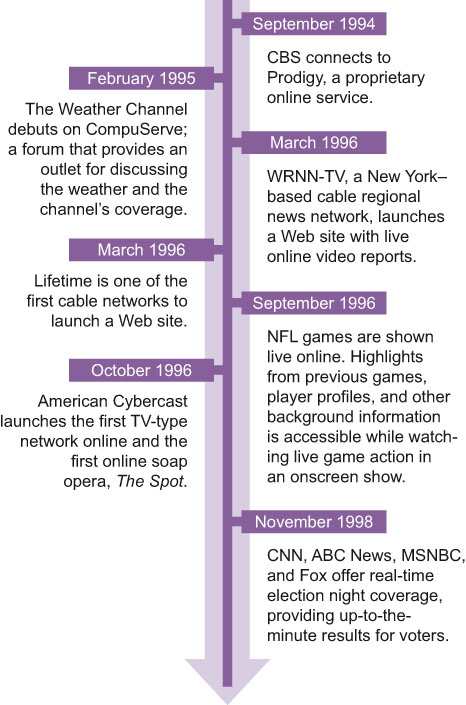

Television’s Migration to the Web

Early television programs such as Amos ’n’ Andy, Life of Riley, Guiding Light, You Bet Your Life, and The Lone Ranger all originated as radio programs, as did many other shows televised in the 1950s. Given the ability of television to bring so much more life to a program than radio ever could, producers transformed radio shows into exciting, dynamic television programs.

Many ardent fans have long hailed television as the ultimate form of entertainment. Television can be watched anytime, anywhere, and choosing what to watch is as easy as pushing a button or flicking a switch. Yet despite the popularity of watching television, the viewing public is always looking for new forms of entertainment.

Over-the-air television was once the primary medium for news and entertainment. Although cable was established early in the life of television, it did not take hold with viewers until the 1970s. More recent technologies, especially satellite, gave rise to newer means of program delivery, and the Web itself was hailed as the ‘television of the future.’

In the mid-1990s, the Web was touted as the up-and-coming substitute for television. The physical similarities between a television and a computer monitor, coupled with the promise that online content would soon be as plentiful and exciting as that on television, led people to believe that the Web would soon replace television. The novelty of the Web also drew many television viewers out of plain curiosity. Between 18 and 37% of Web users were watching less television than they had before, and the Internet was cutting more deeply into time spent with television than with other traditional media. On the other hand, the Web may not have affected the time viewers spent with television except perhaps among those individuals who watched little television in the first place.

As the 1990s came to a close, the Web could deliver some short, full-motion videos at best, but it did not evolve into a substitute for television as predicted. Users crossed into the 21st century still hoping that their computers would soon be technologically capable of receiving both Web content and television programs.

Fig. 5.4 Highlights of early Internet television

See It Now

Internet Users

The Internet has come a long way since 1993, when there were about 14 million users (0.3% of the world population). The number of users increased tenfold in the first 10 years of its existence, and by mid-2016, there were about 3.5 billion users (48.6% global penetration), including 279 million in the United States (86.7% of the population), with most going online every day. The U.S., however, does not have the highest Internet penetration rate; that honor goes to the United Kingdom with 89.9%. Other countries close to the U.S. percentage of Internet users are Germany (86.7%), Japan (86.0%), and France (85.7%).

Estimates of the number of hours users spend online vary widely, but most research indicates that individuals spend about 3.5 to 5 hours per day online, which constitutes about 40% of their daily media use. Although male users originally dominated the Web, women now use it almost as much. Generally, online users tend to be younger than age 65, highly educated, and more affluent than the U.S. population at large, and they tend to live in urban and suburban areas.

Going online is often the first activity of the morning, and many daily routines revolve around the Internet. Completing routine tasks, such as making airline, hotel, or dinner reservations, contacting friends and family, looking up information about any topic, keeping up with the latest news, finding recipes, shopping, and playing games, are conducted online. The Internet has evolved into a multidimensional resource that has become a necessity.

FYI: Demographics of Internet Users (2013)

| Age | |

| 18–34 | 81.2% |

| 35–44 | 83.3% |

| 45–64 | 80.6% |

| 65+ | 64.3% |

| Gender | |

| Male | 79.4% |

| Female | 77.6% |

| Education | |

| less than high school | 53.7% |

| high school graduate | 69.7% |

| some college/associate degree | 82.4% |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 91.5% |

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2014.

FYI: Undergraduate Students and Technology

- 98% use the Internet

- 96% have a smart/cell phone

- 93% have broadband access

- 88% have a laptop

- 86% use social network sites

- 84% have an iPod or other MP3 player

- 58% have a game console

- 9% have an ebook reader

- 5% have a tablet computer

Source: Pew Internet

A Wireless World

To encourage settlement of the American West in the mid-1880s, prominent newspaper editor Horace Greeley urged, “Go west, young man, go west.” If he was alive today, he would probably exhort us to venture into an even newer territory with “Go wireless, young man, go wireless.”

Wireless technology, now commonly called Wi-Fi, became accessible to consumers when Apple introduced its AirPort Base Station in 1999. Base station technology gave way to wireless routers that sent signals to any computer via a wireless card or transmission receiver that needed to be connected to a computer.

Most computers now come equipped with built-in wireless receiving capabilities. The ease and convenience of Wi-Fi has made it the preferred mode of connecting to the Internet. Wi-Fi makes it possible to pick up Internet signals from almost anywhere. These signals cannot be seen or felt, but in many cafés, coffeehouses, airports, universities, and other public places, Internet signals are bouncing off the walls and through the walls. The distance wireless signals reach depends on many factors such as outdoor terrain and number of walls or other obstacles between the router and the device. Like a cell phone, Wi-Fi operates as a kind of radio. Newer 4G (fourth-generation) wireless technologies significantly improve data transmission speed and range over 3G wireless, and newer 5G promises yet greater speed and capabilities. Yet other new wireless technologies, such as Bluetooth, are meant for very short-range connections, such as between a computer and a printer.

Wireless is not perfect. The speed of data transmission fluctuates, it can interfere with satellite radio, and the signals are sometimes blocked by walls and other solid objects. The best wireless signal is obtained in a large, unobstructed space, like a large office that has few ceiling-to-floor walls. Despite these issues, once wireless has been set up, it is quick and easy to use and compatible with most computers and mobile devices.

FYI: Internet Connections (percentage of U.S. homes, 2013)

- Cable modem 42.8%

- Mobile broadband: 33.1%

- No Internet 25.6%

- DSL connection: 21.2%

- Fiber optic: 8%

- Satellite: 4.6%

- Dial-up connection: 1%

(Figures exceed 100%—some homes have multiple connections)

Source: United States Census Bureau, 2014

Internet Resources

World Wide Web

The sheer number of online users attests to the large variety of online content. As astonishing as it seems, there are about 650 million to 1 billion Web sites on the Internet, up from 1 in 1991, 10 in 1992 and 130 in 1993. Moreover, each site contains multiple pages, totaling up to an astounding 14.3 trillion pages of content.

As Tim Berners-Lee pointed out during an interview on PBS’s Nightly Business Report, there are more Web pages than there are neurons in a person’s brain (about 50–100 billion). Further, Berners-Lee claims that more is known about how the human brain works than about how the Web works in terms of its social and cultural impact.

Web information comes in text, graphics, and audio and video formats. The multiformat presentation capability distinguishes it from other parts of the Internet. Point-and-click browsers, first developed in the early 1990s, make it easy to travel from Web site to Web site. Gathering information is as easy as clicking a mouse. The Web is a gateway to other online resources. Email, electronic mailing lists, newsgroups, chat rooms, blogs, and social network sites (SNS) are mostly accessed through a Web site. For example, Facebook is a Web site, and blogs, such as Instapundit, are Web sites.

The Web has changed and along with it the information and entertainment worlds. The Web is altering existing media use habits and the lifestyles of millions of users who have grown to rely on it as a source of entertainment, interactivity, and information.

Zoom In 5.2

To see Web pages from the old days, go to WayBack Machine, http://archive.org/web/web.php, a service that brings up Web sites as they were in the past. The archives go as far back as 1996.

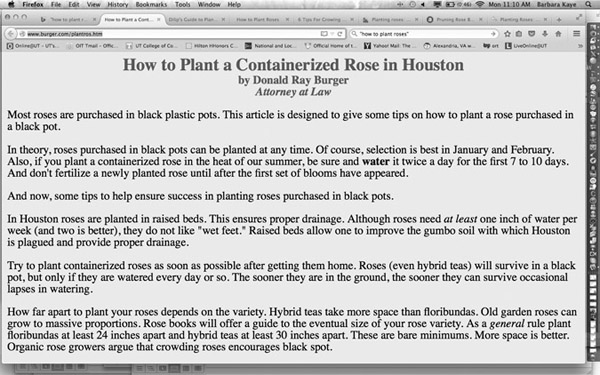

Navigating the World Wide Web

Web browsers such as Firefox and Chrome are based on Hypertext Markup Language (HTML), a Web programming language. Hypertext is “non-linear text, or text that does not flow sequentially from start to finish” (Pavlik, 1996, p. 134). The beauty of hypertext is that it allows nonlinear or nonsequential movement among and within documents. Hypertext is what lets users skip all around a Web site, in any order they please, and jump from the beginning of a page to the end and then to the middle, simply by pointing and clicking on hot buttons, links, and icons.

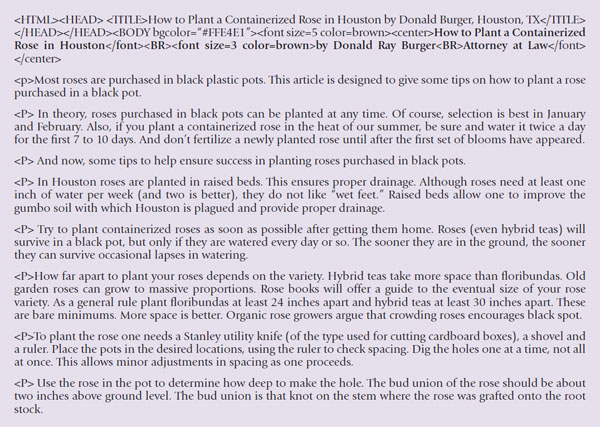

FYI: Hypertext Markup Language (HTML)

HTML is the World Wide Web programming language that basically guides an entire document or site. For Instance, it tells browsers how to display online text and graphics, how to link pages, and how to link within a page. HTML also designates font style, size, and color.

Specialized commands or tags determine a document’s layout and style. For example, to center a document’s title—say, How to Plant a Containerized Rose in Houston—and display it as a large headline font, the tags <HTML><HEAD> <TITLE> are inserted before and after the title, respectively, like this:

<center><H1><I>How To Plant a Containerized Rose In Houston </TITLE> </HEAD></HEAD>

The first set of commands within the brackets tells the browser to display the text centered and in headline bold font. The set of bracketed commands containing a slash tells the browser to stop displaying the text in the designated style.

The HTML source code for most Web pages can be viewed by users. In Firefox, click on the Tools pull-down box in the browser’s tool bar and then click on the Web Developer option. Then click on Page Source.

Fig. 5.5 Simple text-based Web site http://www.burger.com/plantros.htm

Photo courtesy of Donald Burger

Fig. 5.6 HTML source code for the “How to Plant Containerized Roses in Houston” Web page

Photo courtesy of Donald Burger

All Web browsers operate similarly, yet each has its own unique features and thus markets itself accordingly. The competition among browsers has always been stiff, and market share fluctuates. For example, in the mid-1990s, Netscape Navigator led the U.S. market, but by 2003 Internet Explorer (IE) commanded a 90% share of users, which left Netscape with only about a 7% share and Mozilla and other browsers fighting for the remaining market.

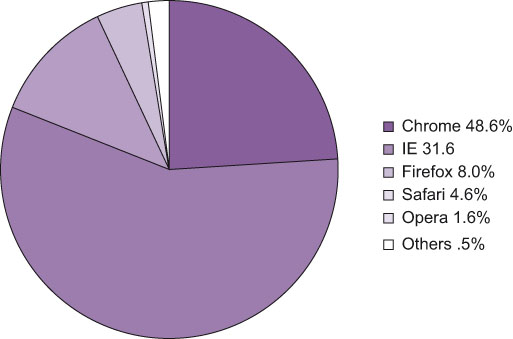

A decade and a half into the new millennium, the two pioneering browsers, Mosaic and Netscape Navigator, are now defunct, having been replaced with more sophisticated ones such as Firefox, and newcomer Google Chrome, which is still the most widely used browser. IE’s market share has slipped to 31.6% and Firefox is a distant third capturing about 8% of Internet users, with the rest of the online market using several other less popular browsers. While still trying to become the number-one browser in the U.S., Google Chrome dominates globally with 62% of the South American market and 49% of the Asian market.

Fig. 5.7 Browser market share

Source: Web Browser Market Share for June 2016. CP Entertainment, 2016

America Online was also a popular way to access online content, but it was more than just a browser. America Online was a proprietary online content provider. Sometimes the term ‘walled garden’ was used to describe America Online’s business model because only subscribers could access certain services. In 1997, almost half of all U.S. homes with Internet access had it through America Online. In 2000, America Online merged with Time Warner, and several years later its name changed to AOL. Through the years, AOL shed its model as a proprietary service and became an Internet portal, similar to Yahoo!. AOL is now a news and information site and offers free access to the Internet, email accounts, and other online resources.

Electronic Mail

Electronic mail, or email, is one of the earliest Internet resources and one of the most widely used applications. The first known email was sent from UCLA to Stanford University on October 29, 1969, when researchers attempted to send the word ‘login.’ They managed to send the letter L and then waited for telephone confirmation that it had made it to Stanford. They then sent the letter O and waited and waited until it arrived. Then they sent the letter G, but due to a computer malfunction, it never arrived. Just as the letter S was the first successful transatlantic radio signal, the letters L and O made up the first successful email message.

Email has come a long way since that first attempt. About 200 billion email messages fly through the global cyberspace every day from more than 4 billion accounts. Approximately 56% of all emails are not wanted (43% spam, 13% other nonessential). Business users send and receive an average of 141 emails per day, accounting for about 70% of all email traffic. The number of personal emails is decreasing as consumers turn to social networking, instant messaging, texting, chatting, and other forms of digital communication.

Zoom In 5.3

Contact this spam-fighting organizations and Web sites for more information:

- Coalition Against Unsolicited Commercial Email (CAUCE): www.cauce.org

The rise of email and the creation of online marketing and billing, business-to-business email, and new systems for collecting and verifying online signatures have reduced reliance on the United States Postal Service (USPS). The volume of mail handled by the USPS has been declining in recent years. From 2000 to 2009, volume declined from 208 billion pieces of mail to 177 billion and to 155.4 billion in 2014. Because there are now more emails sent each day than letters and packages through the USPS each year, the U.S. Postmaster General had asked Congress to allow the USPS to cut delivery from 6 days a week to 5 days to save money in fuel, vehicle wear and tear, and employee wages and benefits. Congress had planed on addressing the issue in 2017. However, after USPS struck an agreement with Amazon to deliver its packages on Sundays, enacted cost savings measures in operations, and enjoyed a 10% increase in volume of holiday packages and mail, it realized a net profit in 2015 and is set to expand rather than cut back on services.

YouTube

YouTube differs from other interactive Web sites in that it is specifically used for sharing video. Created in 2005 and acquired by Google in October 2006, YouTube is now one of the most widely used sites. Each month, slightly more than 1.3 billion unique users watch more than 6 billion hours of videos and short clips that range from professionally produced movie and television shows and musical performances to amateur content such as homemade videos of cats playing and people doing stupid things and talking about whatever. Every minute, 300 hours of video are uploaded to the site for open-access viewing.

Blogs

Blogs (originally dubbed Weblogs) are a type of Web site that allows users to interact directly with the blog host (blogger). It is hard to know exactly when the first blog came online, but the term was coined in 1997. Blogs have been part of the Internet landscape since the late 1990s, but they became popular shortly after September 11, 2001. These diary-type sites were an ideal venue for the outpouring of grief and anger that followed the terrorist attacks on the United States. Blogs are now exceedingly popular, and the number of blogs has proliferated to an estimated 250 million.

Blogs are places where online intellectuals, the digital and politically elite, and everyday people meet to exchange ideas and discuss war and peace, the economy, politics, celebrities, and myriad other topics without the interference of traditional media. As such, bloggers are part of a tech-savvy crowd who often scoop the media giants and provide more insight into current events than the traditional media.

Blogs are free-flowing journals of self-expression in which bloggers post news items, spout their opinions, criticize and laud public policy, opine about what is happening in the online and offline worlds, and connect visitors to essential readings. A blogger may be a journalist, someone with expertise in a specific area such as law or politics, or an everyday person who enjoys the exchange of opinions. Blog readers (those who access a blog) post their comments about a current event, issue, political candidate, or whatever they want to the blogger. These comments are often accompanied by links to more information and analysis and to related items. The blogger posts the blog readers’ comments and links and adds his or her own opinions and links. Blog readers are attracted to the freewheeling conversation of blogs and to the diverse points of view posted by the blogger and other blog readers.

Moving beyond the typical blog are videologs, also known as vlogs. Vlogs are kind of mini-video documentaries. Commentaries, rants, and raves are all presented as full-motion video. Anyone equipped with a digital video camera and special software can produce his or her own vlog.

Fig. 5.8 Anyone can write a blog.

Photo courtesy of iStockphoto. © AlexValent, image #3220999

Career Tracks: Glenn Reynolds. Blogger. InstaPundit.com

Fig. 5.9 Glenn Reynolds

What is your job?

I’m Professor of Law at the University of Tennessee. I also write a twice-weekly column for USA Today. Before coming to Tennessee I went to Yale Law School, clerked for a federal judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, and practiced law at the Washington, DC, office of a Wall Street law firm.

What gave you the idea of starting your blog?

In 2000/2001 I was operating some music Web sites and reading some of the very first blogs—Kausfiles, Andrew Sullivan, Virginia Postrel, etc.—when I ran across the Blogger.com site, which Ev Williams was then running from his basement, I believe. I had been using a program called Dreamweaver, which was very labor intensive. With Blogger you just logged on to a Web site, typed in your post, and hit ‘publish.’ It was so easy, I decided to give blogging a try. Also, I was teaching Internet law and wanted to keep up with new things. I didn’t expect it to last so long, or to have such a large audience.

Describe your blog?

Today, Instapundit gets around 500,000–600,000 page views on a typical weekday. It consists mostly of short posts on things that interest me. Often it’s just a link with a brief description, sometimes I’ll make a few pithy observations, and sometimes I’ll produce a lengthy post incorporating reader comments. It just depends. I tend to put politics, war, and the ‘heavier’ stuff in the morning, with science, technology, and pop culture in the afternoon, though that’s more of a guideline than a rule. Basically, I post whatever I find interesting. I’ve been bringing in guest bloggers occasionally for years as well.

How is PJ Media connected to Instapundit?

PJ Media is a company I started with a couple of other bloggers back in 2005. I occasionally write for their site, and we share hosting and advertising. They also have editors who will keep an eye on my blog when I’m busy and fix typos, etc.

What do you do on a daily basis to keep your blog going?

On a typical day, the blog will have about 30–50 posts. Since about ten years ago, I’ve been able to write posts in advance and set a time when they will self-publish, a technological improvement that has made my blogging life much easier. I usually set up a skeleton for the day the night before, so that if I get busy there will still be new stuff appearing every hour. Then I add breaking news and other new stuff that comes up throughout the day as I have time. I get a lot of my links from my readers, and a lot from Twitter, where I follow a lot of people from different circles. Sometimes I travel to events—conferences, protest rallies, etc.—and report on them via my blog, posting photos and videos that I shoot and edit myself.

What advice do you have for students who might want to start a blog?

Don’t start a blog if you can’t handle criticism. On the Internet, everyone’s a critic. Fortunately, I’m pretty thick skinned. Focus on stuff that interests you, not on copying blogs that you like. The Internet audience is vast, so if you’re good at blogging even on a niche target you can build up a big audience. Cultivate a personal relationship with your readers—that’s what distinguishes a blog from a Big Media outlet. And don’t be afraid to mix up your interests: The joke about my blog is ‘come for the politics, stay for the nanotechnology.’ Specialization is good, but too much specialization is for insects.

Also, bear in mind that your blog is a marketing tool for your skills. I was writing the occasional op-ed for newspapers before I started blogging (many law professors do that sort of thing), but I’ve gotten a lot of higher-level writing opportunities because editors know my general take on things, know that I can write, and know that I can write fast. Plus, when I publish a piece and then post a link on my blog, it brings traffic of its own. In today’s click-conscious environment, that’s a big advantage that comes with having your own audience.

Electronic Mailing Lists

Electronic mailing lists are similar to email, in that messages are sent to electronic mailboxes for later retrieval. The difference is that email messages are addressed to individual recipients, whereas electronic mailing list messages are addressed to the electronic mailing list’s address and then forwarded only to the electronic mailboxes of the list’s subscribers.

Electronic mailing lists connect people with similar interests. Most lists are topic specific, which means subscribers trade information about specific subjects, like college football, gardening, computers, dog breeding, and television shows. Mailing lists are commonly used in the workplace to connect personnel within a department, or managers, or others with similar titles and duties. Many clubs, organizations, special-interest groups, classes, and media use electronic mailing lists as a means of communicating among their members. Most electronic mailing lists are open to anyone; others are available only on a subscribe-by-permission basis. Electronic mailing lists are often referred to generically as listservs; however, LISTSERV is the brand name of an automatic mailing list server that was first developed in 1986.

Newsgroups

Similar to electronic mailing lists, newsgroups bring together people with similar interests. Web-based newsgroups are discussion and information exchange forums on specific topics, but unlike electronic mailing lists, participants are not required to subscribe, and messages are not delivered to individual electronic mailboxes. Instead, newsgroups work by archiving messages that users access at their convenience. Think of a newsgroup as a bulletin board hanging in a hallway outside of a classroom. Flyers are posted on the bulletin board and left hanging for people to sift through and read.

Chat Rooms

A chat room is another type of two-way, online communication. Chat participants exchange live, real-time messages. It is almost like talking on the telephone in that a conversation is going on, but instead of talking, messages are typed back and forth. Chat is commonly used for online tech or customer product support. Chat is very useful for carrying on real-time, immediate-response conversations.

Instant Messaging

Instant messaging (IM) is another way to carry on real-time typed conversations. Different from chat-room conversation, which can occur among anonymous individuals, instant messaging takes place among people who know each other. Instant messaging is basically a private chat room that alerts users when friends and family are online and available for conversation. Because users are synchronously linked to people they know, IM has a more personal feel than a chat room and is more immediate than email. Some IM software boasts video capabilities to create a more realistic face-to-face setting.

‘Instant messaging’ differs from ‘text messaging’ in that IM is Internet-based on computer-to-computer connections, whereas texts are sent to and from cell phones and other handheld devices. Instant messaging services were once the domain of America Online (AOL) and Microsoft, but Skype, Facebook, and Google have since added IM applications.

Social Network Sites

Millions of online users are drawn to social network sites (SNS) as a means of keeping in touch with friends and family and building a network of new ‘friends’ based on shared interests and other commonalities, such as politics, religion, hobbies, and activities. Although social network sites hit their stride in the late-2000s, they have been in existence since the late 1990s. SNS such as sixdegrees.org, AsianAvenue, BlackPlanet, and LiveJournal were the precursors to the second wave of SNS, which includes MySpace and Facebook. About three-quarters of online users have a profile on at least one of the estimated thousands of SNS. But of all SNS, about 200 have emerged as the most popular, with Facebook leading the pack. The number of social network users over the age of 50 almost doubled between 2009 and 2010, but they are still more likely to network with friends and family using email, whereas those between the ages of 18 and 29 are just as likely to use both SNS and email. The growing popularity of social network sites is signaling a shift in how consumers are using the Internet.

Zoom In 5.4

Go to any search service, find a list of blogs, newsgroups, and social network sites, and click on some you are unfamiliar with. Join some you find interesting.

Twitter took only a few years to infiltrate the social network world. Twitter has moved beyond connecting small groups of friends to being a way to reach millions of followers at once. Celebrities, politicians, and companies use Twitter to promote themselves, their ideas, and their products to their followers. Although messages, known as ‘tweets,’ are limited to 140 characters, they are long enough to make a point, and it is thrilling to be part of a conversation that includes the rich and famous. Twitter is defined as a microblog because of the limited length of a tweet. But microblog or not, there is nothing micro about the size of some users’ networks, which reach hundreds of thousands or even millions of followers. The downside of Twitter is that once a message is out there, it cannot be taken back. So one wrong word or misstatement can and probably will come back to haunt the author. Some users have lost their jobs or have been socially ostracized because of something they said on Twitter. Although proponents love the collection of voices, critics claim that most tweets are nothing but useless babble that wastes time.

FYI: Most Popular Online Activities (2012)

| Percentage of Users | |

| Sending or reading email | 92% |

| Using search engines to find information | 89% |

| Search for a map or driving instruction | 86% |

| Research a product or service | 81% |

| Check the weather | 80% |

| Look for health or medical information | 73% |

| Get travel information | 73% |

| Read news and current affairs | 73% |

| Shopping | 71% |

| Visit a local, state, or federal government site | 66% |

| Make travel reservations | 64% |

| Surf the Web for fun to pass the time | 62% |

Source: Pew Internet and American Life Project

FYI: The Internet of Things

The Internet of Things (IoT) is one of the newest buzz phrases. The term refers to the interconnections of everyday objects through the Internet. For example, smartphone-programmable thermostats, washers and dryers, and lights, cars with built-in sensors, medical and fitness tracking devices are IoT technologies. Intel chips that drive IoT generated 2.1 billion in revenue in 2014, and IoT gadgets were all over the 2015 Consumer Electronics Show.

The World Wide Web and the Mass Media

Many Internet users are abandoning traditionally delivered radio and television for Internet-delivered programming. Audio Web sites and services like iTunes offer an array of musical choices well beyond local over-the-air radio, and it is so much more convenient to watch video clips or full-length programs online than to wait for a television program to come on.

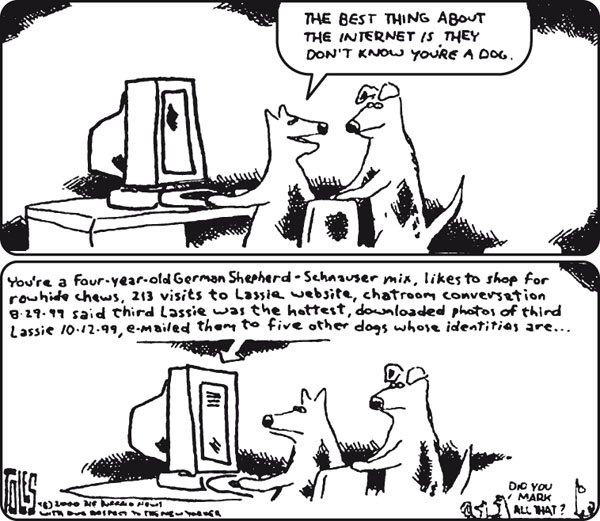

One of the main concerns about online content does not regard delivery but the nature of the content itself. Decentralized information dissemination means that online materials are often not subjected to traditional methods of source checking and editing. Thus, they may be inaccurate and not very credible.

When listeners tune to radio news or viewers watch television news, they are generally aware of the information source. They know, for instance, that they are listening to news provided by National Public Radio (NPR) or watching the ABC television network. In addition, broadcast material is generally written and produced by a network or an independent producer or credentialed journalist. Audiences rely on these sources and believe them fairly credible. But mainstream media suffer from low public opinion. About three-quarters of people think the news media are influenced by powerful groups and favor one side and that reporters try to cover up their mistakes.

Internet users, especially novices, cannot be sure that what they read and see online is credible and accurate, especially if it is posted by an unfamiliar source. Many Web sites are hosted by reliable and known sources, such as CNN and NBC. However, anyone can produce a Web page or post a message on a blog, a social network site, bulletin board, or chat room, bringing into question source credibility. Such user-generated content (UGC) now accounts for more online information than that produced by journalists, writers, and other professionals. Internet users must grapple with the amount of credence to give to what they see and read online. Thus, it is a good idea to sift through cyber information very carefully. It is the user’s responsibility to double-check the veracity of online information. Users should be cautious of accepting conjecture as truth and of using Web sources as substitutes for academic texts, books, and other media that check their sources and facts for accuracy before publication.

FYI: How Many Online?

This table shows the number of Internet users by region (June 2016).

| World Regions | Internet Users | % of population |

| North America | 320.0 million | 89.0% |

| Europe | 614.9 million | 73.9% |

| Oceania/Australia | 27.5 million | 73.2% |

| Latin America/ Caribbean | 374.4 million | 59.8% |

| Middle East | 129.4 million | 52.5% |

| Asia | 1.76 billion | 43.6% |

| Africa | 333.5 million | 28.1% |

Source: World Internet Users, 2016

FYI: Home Internet Access

Percentage of U.S. Households (modem or broadband)

| 2015 | 84.0% |

| 2014 | 79.0% |

| 2013 | 78.1% |

| 2012 | 74.8% |

| 2011 | 71.7% |

| 2010 | 71.1% |

| 2009 | 68.7% |

| 2008 | 63.6% |

| 2007 | 62.0% |

| 2006 | 60.2% |

| 2005 | 58.5% |

| 2004 | 56.8% |

| 2003 | 55.1% |

| 2002 | 52.9% |

| 2001 | 51.0% |

| 2000 | 42.0% |

Sources: Leichtman Research Group, 2015; Ranie & Cohn, 2014; U.S. Census Bureau, 2014

Online Radio Today

Almost all of the nation’s 15,400 broadcast radio stations have some sort of Internet presence. Online radio offers so much more to its audience than broadcast stations, which are limited by signal range and audio-only output. Internet radio delivers audio, text, graphics, and video to satisfy a range of listener needs.

Early online radio was difficult to listen to and hard to access, and it took an excruciatingly long time to download a song. Moreover, the playback was tinny and would often fade in and out. Few Internet users had computers powerful enough to handle audio, and few stations were streaming live content. In the late 1990s, online audio was still so undeveloped that only 5 to 13% of Web users reported that the amount of time they spent listening to over-the-air radio had decreased in favor of online audio.

Although some radio station Web sites retransmit portions of their over-the-air programs, other audio sites produce programs solely for online use and are not affiliated with any broadcast station. Many audio sites offer very specific types of music. A site may feature, for example, Swedish rock, Latin jazz, and other hard-to-find music. There are hundreds of audio programs available on search services and radio program guides that give the time and URL of a live online program or a long list of music-oriented Web sites.

Radio station Web sites are promotional by nature, but most also offer local news and entertainment and have the capability of transmitting audio clips or delivering live programming. However, doing so has hit a snag. Streamed audio is a great way for consumers who do not have access to a radio or who live outside the signal area to listen to their favorite station. But after many complaints from record labels, artists, and others, the Library of Congress implemented royalty fees, requiring Webcasters to pay for simultaneous Internet retransmission. The fees vary from per-song costs to a percentage of gross revenues, depending on the online pricing model. Whatever the exact amount charged, labels and artists claim this fee is too low, while online music providers say it is too high.

The advantage of both over-the-air radio and online radio is that they can be listened to while working or engaging in other activities. But online radio has a distinct advantage over AM/FM radio—users can listen to stations from all over the world, and they can choose from a huge selection of music genres. If none of the local radio stations play a listener’s favorite music, he or she can go online and find many stations that do. So Internet users may not be turning their backs on music radio but rather abandoning the old over-the-air delivery for online delivery, which provides clear audio at convenient times and can be set to play their favorite types of music.

Over-the-air broadcast radio stations are concerned that their listening audience is abandoning them for online music. However, despite strong growth in online radio listenership, over-the-air AM/FM listeners remain loyal. Although some studies claim that radio listening is decreasing among Internet users, others claim that radio is gaining favor among those who go online. Digital delivery adds to audio listenership, but it is not a substitute for over-the-air delivery, except perhaps for adults aged 18 to 24, half of whom said they spend less time listening to broadcast radio in favor of online radio. Local news and information is the strongest draw to broadcast radio, and it is the main reason half of U.S. adults tune in. Research indicates a trend in which broadcast radio is relied on for nonmusic programming, whereas digital radio is used more for music, especially for learning about new tunes. Indeed, about two-thirds of online users say they learn more about new songs and bands from the Internet than from the radio, and almost one-half often look at the media player/computer to see the name of the song or artist.

The audience for streaming Internet radio continues to grow as sound quality improves and as listeners embrace newer, more portable playback devices such as laptops, smartphones, and tablets, and customizable services such as Spotify and Pandora. There were about 93 million Internet radio listeners (30% of the U.S. population) in 2010, and just 5 years later, that number rose to almost 170 million users (52%).

FYI: U.S. Audio Listening: 28 Hours per Week

- Broadcast radio (AM and FM): 16 hours

- Downloads, vinyl, CDs, tapes: 5 hours 30 minutes

- Streaming services: 3 hours 20 minutes

- Satellite radio: 2 hours and 10 minutes

- Podcasts: 30 minutes

- Other (e.g., audiobooks): 30 minutes

Source: Stutz, 2014

Total U.S. music revenue in 2013 hovered at about $7 billion, about half of what it was before digital music changed the industry forever. As of 2013 there were about 400 licensed digital music services, such as iTunes, Rhapsody, and Groove Music, which account for about $1.6 billion in digital track sales (1.3 billion units) and $1.2 billion in digital album sales (118 million units). But digital downloads are giving way to custom streaming services. The portion of revenue generated by streaming jumped from 3% in 2007 to 21% in 2013 to 33% in 2015. Unfortunately, the revenue generated by online downloads and streaming does not make up for the downturn in CD sales, which have been decreasing since 2000.

File sharing and downloading, both legal and illegal, spawned a new way to obtain and listen to music and other audio files. Gone are the days when a song or audio clip could take up to an hour to download and then be so garbled that it was not worth the effort. Cybercasting, either by live streaming or by downloading, is a great way for little-known artists who have a hard time getting airplay on traditional stations to gain exposure. Additionally, listeners can easily sample new music, and links are often provided to sites for downloading and purchasing songs and CDs. Downloading music from online sites has boomed in recent years, especially since the advent of the iPod and other portable digital music devices.

And the Recording Industry Association of America is still going after music pirates. Since the first round of lawsuits, RIAA has filed more than 30,000 more. In the summer of 2009, a 32-year-old Minnesota mother of four and a Boston University graduate student were both fined for illegally downloading music. The woman was fined $80,000 for each of 24 songs she illegally downloaded, for a total judgment of $1.9 million—for songs that only cost 99 cents each; the graduate student was fined $675,000 for illegally downloading and sharing 800 songs between 1999 and 2007. Both fines were later settled for lesser amounts.

The RIAA is serious about getting its message out: “Importing a free song is the same as shoplifting a disc from a record store” (Levy, 2003b, p. 39). The RIAA’s legal and educational efforts have paid off; just over half of those who regularly downloaded music illegally claimed that the crackdown has made them less likely to continue to pirate music. Prior to the initial lawsuits, only about 35% of people knew file sharing was illegal; now about double that percentage is aware of what constitutes illegal downloading. Further, the percentage of U.S. Internet users who downloaded music illegally dropped from 29% to 9% from 2000 to 2010. Although some online users might not think there is much harm in illegally downloading a song here and there, the scope of the problem shows otherwise—illegal downloads cost the U.S. economy $12.5 billion annually.

FYI: Challenges of Internet Radio

- With a slower connection, the delivery may be choppy, with dropped syllables and words.

- High treble and low bass sounds are diminished as the data squeeze into available bandwidths.

- Without external computer speakers, quality of sound is often like listening to AM radio or FM mono radio, at best.

- A high-speed cable modem or direct Internet access with increased bandwidth is needed to hear audio of FM stereo quality and even CD-quality sound.

- Downloading audio files can still take longer than a user is willing to wait.

- The number of simultaneous listeners is often limited.

- A music player, tablet, or smartphone is needed for portability.

FYI: Benefits of Internet Radio

- Web audio files can be listened to at any time.

- Netcasts can be listened to from anywhere in the world, regardless of their place of origin.

- Online radio can be heard and seen. Song lyrics, rock bands in concert, and news items can be viewed as text, graphics, or video.

- Online radio supports multitasking, or the ability of users to listen to an audio program while performing other computer tasks and even while surfing the Web.

- Online music services customize individual playlists to a listener’s preferences.

Zoom In 5.5

Get both sides of the story about file sharing. First, go to www.riaa.com to learn the point of view of a music-licensing agency. Then go to www.eff.com for information from organization that does not consider online file sharing a crime.

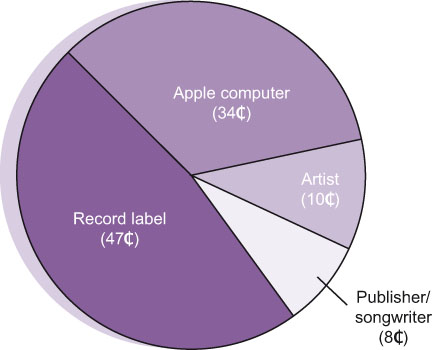

Fig. 5.10 99 cents per download. So where does your 99 cents go when you pay to download a song from a legal music site? Here’s an example from Apple’s iTunes.

Source: Spors, 2003

FYI: Top Digital Song Download Sales 2015

| Artist, Song | Total Sold |

| Mark Ronson featuring Bruno Mars, “Uptown Funk” | 5,529,000 |

| Ed Sheeran, “Thinking Out Loud” | 3,976,000 |

| Wiz Khalifa featuring Charlie Puth, “See You Again” | 3,801,000 |

| Adele, “Hello” | 3,712,000 |

| Maroon 5, “Sugar” | 3,343,000 |

| Walk the Moon, “Shut Up and Dance” | 2,986,000 |

| Fetty Wap, “Trap Queen” | 2,730,000 |

| OMI, “Cheerleader” | 2,698,000 |

| The Weeknd, “The Hills” | 2,586,000 |

| Taylor Swift featuring Kendrick Lamar, “Bad Blood” | 2,580,000 |

Source: Caulfield, 2016

FYI: Adele Sets a Record

Adele’s “25” holds the record for the most downloads in a calendar year with 2.31 million sales in 2015. This record is especially amazing considering that the album was not released until mid-November 2015.

Podcasting

In addition to music, podcasts are another type of audio file that has caught the ears of online listeners. Podcasts are audio-only programs produced by radio and television stations and networks, talk show hosts, celebrities, professors, and anyone who thinks he or she has something interesting to say about topics such as movies, music, popular culture, cooking, and sports. Many corporate media Web sites—such as npr.org, espn.com, and abc.go.com—offer hundreds if not thousands of podcasts.

One of the first times that the term ‘podcasting’ was mentioned was in an issue of the British newspaper The Guardian in 2004. The term is a combination of the acronym ‘personal on demand’ (POD) and the word ‘broadcasting.’ According to Jason Van Orden, author of Promoting Your Podcast, a podcast is “a digital recording of a radio broadcast or similar programme, made available on the Internet for downloading to a personal audio player” (Van Orden, 2008).

The purpose of a podcast is not just to transfer readable information to audio format but to provide users with updated and sometimes live online audio. Different from a typical audio file, a podcast is created through Real Simple Syndication (RSS) feed, a standardized format used to publish frequently updated materials, such as news headlines and blog entries. Technically, a podcast is an audio file embedded in an RSS feed. Podcasts are subscribed to through a software program, known as a podcatcher, that syncs podcasts to a computer-connected MP3 player. Podcasts free listeners from media, business, and personal schedules, and they can be archived on a computer or burned onto a CD.

With podcasting as the new downloading rage, the question arises as to how media organizations consider people who download music and other audio programs. If someone subscribes to the podcasts of National Public Radio’s Talk of the Nation, should they be considered a radio listener or a podcast listener? Perhaps the consumption of audio content is what matters rather than the mode of delivery. As the number of podcasts and podcasters surge, the media have much to consider; they need to redefine themselves and rethink their methods of content delivery and how to measure their online and mobile audiences.

It is impossible to know the definitive number of podcasts, but it is estimated there are about 250,000 unique podcasts in over 100 languages, of which about 115,000 are recorded in English. Apple reports that in 2013, the number of podcasts downloaded through iTunes reached 1 billion. Class lectures, interviews, tutorials, stories, training, and speeches are often podcast. Some of the most common podcast topics include, music, technology, comedy, education, and business.

About 33% of the U.S. population has listened to a podcast. With about 320 million people in the United States, that percentage translates into 105 million listeners—an incredibly high number considering that podcasting first appeared online only in 2004. Slightly more males (54%) than females (46%) listen to podcasts, and just over one-half (52%) of the podcast listening audience is between the ages of 12 and 34. Further, podcast listeners have a higher-than-average annual income.

One of the most critically acclaimed podcasts to date first appeared in October 2014. Serial delves into police investigation of the 1999 death of an 18-year-old woman in Baltimore, MD. The victim’s boyfriend was found guilty and sentenced to life plus 30 years despite his pleas of innocence. Each of the 12 episodes dramatically unravels the story of the woman’s strangling and painstakingly retraces each step of the investigation, including scrutinizing witnesses’ testimony and analyzing court documents. The gripping audio documentary becomes especially compelling as the boyfriend’s guilt comes into question—was he wrongly convicted? Serial has caught the ears of about 40 million listeners, including lawyers for Project Innocence, who will be retesting DNA samples found on the victim’s body.

FYI: Top 10 Podcasts 2015 (by number of downloads)

- Fresh Air (NPR)

- Serial

- Stuff You Should Know

- This American Life

- Planet Money

- Radiolab

- Freakanomics Radio

- The Joe Rogan Experience

- The Nerdist

- The Dave Ramsey Show

Source: Eadiccio, 2016

Using Television, Using the Web

The Internet caught on largely because it is used the same way television is watched—sitting in front of a screen that displays text, graphics, audio, and video. Switching from Web site to Web site is, in some ways, similar to changing television channels. When Internet users switch from one Web site to another, they do so by typing in a uniform resource locator (URL), by simply clicking on a link, or by clicking on their browser’s Back and Forward buttons, which function like the up and down arrow keys on a television remote-control device. Even the lingo of Web browsing is borrowed from television. Commonly used terms such as ‘surfing’ and ‘cruising’ are used to describe traversing from one Web site to another and are also used to describe television channel-switching behavior.

Now, new combo computer monitors/televisions further integrate the utility of the Internet and television. Many televisions (smart TVs) come with built-in Wi-Fi, a Web browser, icons that link to Hulu and Netflix, and connections to DVD players, DVRs, and computers. On some televisions, the picture is shown in one window and computer functions such as email in another window on the same screen. Television and the Internet are functionally combined in many ways and inseparable in the minds of many viewers.

FYI: Top Multiplatform Properties

Monthly Rankings: January 2016

| Property | Unique Visitors |

| Google Sites | 245.2 million |

| 207.6 million | |

| Yahoo! Sites | 205.4 million |

| Microsoft Sites | 202.9 million |

| Amazon Sites | 183.0 million |

| AOL Inc. | 169.9 million |

| Comcast NBC Universal | 161.0 million |

| CBS Interactive | 156.4 million |

| Apple Inc. | 139.8 million |

| Mode Media | 139.2 million |

Source: comScore, 2016

Audience Fragmentation

Traditional broadcast television programs were created to appeal to millions of viewers. Then cable television came along and altered programming by introducing narrowcasting, in which topic-specific shows were specifically created to appeal to smaller but more interested and loyal viewers. The Internet has taken narrowcasting a step further by cybercasting information targeted to smaller audiences. In this way the Web can be thought of as a “personal broadcast system” (Cortese, 1997, p. 96).

Television industry executives are worried that the Web is further fragmenting an already fragmented audience. In the early days of television, viewership was mostly shared among three major broadcast television networks, which were and still are fiercely competitive. (Even a small gain in the number of viewers means millions of dollars of additional advertising revenue). Cable television, which offers hundreds of channels, has further fragmented the viewing audience. Now, as viewers increasingly subscribe to cable and satellite delivery systems and turn to the Web as a new source of information and entertainment, the size of television’s audience is eroding further—and, with it, potential advertising revenue.

To help offset audience loss and to retain current viewers, most television networks have established Web sites on which they promote their programs and stars and offer insights into the world of television. Many new and returning television shows are heavily promoted online with banner ads, a Web site, and sometimes blogs, Twitter, bulletin boards, and chat rooms. As one television executive said, “The more they talk about it, the more they watch it” (Krol, 1997, p. 40). Television program executives view the Internet as a magnet to their televised fare.

Selecting Television Programs and Web Sites

Wielding a television remote-control device gives viewers the power to create their own patterns of television channel selection. Some viewers quickly scan through all the available channels; others slowly sample a variety of favorite channels before selecting one program to watch. Television viewers tend to surf through the lowest-numbered channels on the dial (2 through 13) more often than the higher-numbered channels. Unlike television, however, the Web does not have prime locations on its ‘dial,’ so one Web site does not have an inherent location advantage over another. However, sites with short and easy-to-remember domain names may be accessed more frequently than their counterparts with longer and more complicated URLs.

As users become adept at making their way around the Web, customized styles of browsing are emerging. Some users access only a set of favorite sites; others are not loyal to any particular site. When viewers sit down to watch television, they usually grab the remote control and start pushing buttons. But instead of randomly moving from one channel to another, most viewers have developed a favorite set of channels they go through first. Most viewers’ channel repertoire consists of an average of 10 to 12 channels, regardless of the number of channels offered by their cable or satellite systems.

Selecting a television program or Web site also depends on the mood and goals. Sometimes viewers select television programs and Web sites instrumentally; they are looking for specific information. They pay attention to the content and purposely switch channels or move from site to site because they have a goal in mind. At other times, the television or Internet is turned on out of habit or to pass the time. Viewers ritualistically surf through the channels or click on links, paying attention to whatever seems interesting. The Web generally requires more attention than television, but many sites are designed for users to kick back and become a ‘Web potato’ instead of a ‘couch potato.’ Longer video and audio segments and text are designed to minimize scrolling and clicking and to keep users glued to the screen for longer periods of time.

Television-viewing behaviors have transferred to using the Web. As users become more familiar with online content, they develop their own repertoire of favorite sites that they link to regularly. These preferred sites are easily bookmarked for instant and more frequent access.

Similar to how television adapted its programs from radio, many Web sites reproduce material that has already appeared in traditional media. For instance, many news sites and other media-oriented sites are made up largely of text taken directly from the pages of newspapers, magazines, brochures, radio and television scripts, and other sources. In some cases, however, materials are adapted more specifically to the Web. The text is edited and rewritten for visual presentation and screen size, and short, summary versions may be linked to longer, detailed ones. Bold graphic illustrations, audio and video components, and interactive elements also enliven Web pages and give them a television-like appearance.

Television-oriented sites are still typically used to promote televised fare and are among the most popular Web sites, excluding search services. Each of the big three television networks (ABC, NBC, CBS) and dozens of cable networks tried out the Web for the first time in 1994, and all now have their own Web sites.

FYI: Top U.S. Online Video Content Properties (January 2016)

| Property | Total Unique Viewers |

| Google Sites (including YouTube) | 233.9 million |

| 174.0 million | |

| Yahoo! Sites | 84.2 million |

| Vimeo | 47.1 million |

| CBC Interactive | 45.3 million |

| Comcast NBC Universal | 45.0 million |

| VEVO | 43.6 million |

| Warner Music | 39.4 million |

| Maker Studios | 38.9 million |

| Microsoft sites | 36.5 million |

Source: comScore, 2016

Is the Web Stealing Television’s Viewers?

Just as radio’s audience was encroached on by broadcast television and, in turn, broadcast television’s viewers were drawn to cable, many fear that the Web is slowly attracting users away from television. Time spent on the Web is time that could be spent watching television. The advertising industry is especially concerned that when consumers watch programs online, they do not see the commercials that ran in the original broadcast.

Until about the mid-2000s, television was a bit protected from Web pillaging for several reasons. Online technology could not deliver the same clear video and audio/video syncing as television, not all television programs were available online in their entirety, and television-quality original Web programs were scarce. Some Web sites, however, did offer short episodes (Webisodes) of online-only programming.

But that was yesterday. Now, given all of the advances in full-motion video technology, almost every television show is posted on Web sites such as Hulu.com and YouTube.com. Given the Internet’s vast storage capabilities, it is getting easier to go online and watch any program without being tied to a television schedule or a to a cable or satellite company. Viewers who have dropped their cable service and watch television programs solely online are known as ‘cord-cutters,’ and those who have never subscribed are called ‘cord nevers.’ Reports vary on how many television viewers fall into either category. About 15% of U.S. viewers have cut the cable cord, joining the 9% who have never subscribed to cable or satellite. But yet 15% of cable customers say they will never cut the cord. Generally, about 48% of adults watch more programs online than through a cable or satellite service, but that percentage jumps to about 70% for 18- to 35-year-olds.

Fig. 5.11 With the Internet, you can watch online video anywhere.

Photo courtesy of iStockphoto. © adamdodd, image #4481014

The cable industry is very concerned about reaching Millennials. Between 13% and 19% of viewers 18 to 35 get all of their television from Netflix, Hulu, and other such services, compared to about 5% of viewers over 35. Further, Millennials strongly influence household cable decisions. Only about 6.5% of U.S. households have cut the cable cord compared with 12.4% of households that include at least one person 18 to 34 years old. Interestingly, 40% of cord cutters and cord nevers do not subscribe to home broadband/Internet services, meaning they watch streamed programs on their smartphone or tablet.

Millions of viewers are watching television online every day. The top video sites by time spent are Netflix, YouTube, Hulu, and MegaVideo. Viewers are most likely to watch full-length movies on Netflix than on the other services, and thus they spend about 10 hours per month using the service, whereas they spend a little over 2 hours per month watching video on the other sites. Compared to about 135 hours a month watching traditional television, online viewing still has a way to catch up, and no one knows for sure if the gap will narrow and/or how long it will take. Even though Internet technology is the catalyst for changing the culture of television viewing, people love television, and so far it has proven resilient against the lure of online delivery. New smart television sets with built-in Internet and links to Netflix and YouTube are bringing down the barriers that once separated a television set from the Internet and are instead setting up a symbiotic relationship that makes it unnecessary to have both a traditional television set and a separate computer with Internet access.

FYI: A Sampling of Radio and Television Online

| Radio Station Locator | www.radio-locator.com |

| Radio Tower | www.radiotower.com |

| National Public Radio | www.npr.org |

| Radio Free Europe | www.rferl.org |

| Voice of America | www.voa.gov |

| ABC Television | www.abcnews.com |

| BBC iplayer Radio | www.bbc.co.uk/radio |