3. peer influence analysis

Stop me if you’ve heard this one.

A guy walks onto a plane in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in the spring of 2008. He’s a musician starting a tour through Nebraska. He checks his guitar.

Later that day, as he’s getting on the connecting flight in Chicago, he hears a woman say “My God, they’re throwing guitars out there.” And sure enough, the baggage handlers are heaving musical instruments around like sacks of potatoes.

By now, many of you have figured out that the guy is Dave Carroll and the airline is United. If you know the story, you know that Dave Carroll went from being a not-very-well-known local musician to being about as empowered as one guy can get.

The base of Dave’s $3,500 Taylor guitar was smashed.1 United’s baggage claims agents refused to pay the $1,200 cost of the repair, citing a policy about the timeframe in which claims need to be filed. So he took things into his own hands. He wrote a song called “United Breaks Guitars,” spent $150 to make a video for it with his band, and loaded the video onto YouTube in July of 2009.2 It’s a pretty catchy tune, and of course, the video features (dramatized) careless baggage handlers. By that night, twenty-five thousand people had seen it. The Halifax Herald covered it. The Los Angeles Times covered it. So did CNN.

Since then, more than 7 million people have viewed it.

Here’s what life has been like for Dave Carroll since then. He’s been interviewed in the news media two hundred fifty times. He’s schmoozed with Whoopi Goldberg on The View.3 His Web site is getting fifty thousand hits a day. His CDs are selling like mad. CTV, the largest private broadcaster in Canada, hired him as a songwriter. He’s got an endorsement deal with Carlton, a company that makes hard guitar cases. And he’s getting a different kind of gig now—companies are hiring him as a social media expert.

Meanwhile, United Airlines is doing penance for the insensitivity of its baggage handlers and claims agents. Sysomos, a company that monitors online mentions of companies, including sentiment (positive or negative), tracked a spike in social chatter about United Airlines just after “United Breaks Guitars” went live, especially on Twitter.4 Examining sentiment in blogs in the hundreds of posts mentioning United in the quarters before and after the incident, positive sentiment went down from 34 to 28 percent; negative increased from 22 to 25 percent. (The rest were neutral.) And the fallout in traditional media was worse—positive stories dropped from 39 to 27 percent, while negative stories increased from 18 to 23 percent. Six months after “United Breaks Guitars,” requests to talk about it still were coming in to United PR almost daily.

United has changed its policies. Baggage claims agents now have a little more discretion with customers whose special situations warrant the company looking into the claim more closely; United uses Dave Carroll’s video in its training. And the company has begun monitoring social media regularly, so it can respond to people and cut red tape before they get mad enough to broadcast their anger more publicly. But “United Breaks Guitars” continues to resonate, since it reinforces people’s ideas about insensitive airlines. People will be talking about this for a long time to come.

was your last customer Dave Carroll?

Let’s unpack what’s really going on with United and Dave Carroll—or in any case where empowered customers disrupt a company.

In traditional marketing you send out messages to masses of people. You count those instances as “impressions.” You hope your message, repeated frequently enough, impresses your audience. One ad campaign might create 7 million impressions.

Using the reach of YouTube, Dave Carroll created 7 million impressions by himself (and for $150—what’s your TV ad budget?). The baggage handlers and claims agents were his unwitting collaborators. It’s practically an ad campaign run by a single empowered customer.

Now we’ll quantify this phenomenon. At Forrester, we surveyed ten thousand people at the end of 2009.5 We asked about the environments in which they spread influence, like Facebook, Twitter, and blogs. Here’s what we found.6

Within social networks, consumers create 256 billion impressions on one another by talking about products and services each year.7

In social environments like blogs and discussion forums and on sites that feature ratings and reviews, customers generate 1.64 billion posts.8 While we can’t know how many people view each post, based on data we’ve collected about readership of blogs and forums, we estimate that this content creates at least another 250 billion impressions. Combined with the social networks, that’s more than half a trillion impressions in the United States. On average, that’s about eight impressions every day on every person online.

Here’s one way to look at the connections empowered consumers are making. According to Nielsen Online, advertisers delivered 1.974 trillion online ad impressions in the twelve months ending in September 2009, the time period covered by our survey.9 Do the math. People receive roughly one-fourth as many impressions from each other as they do from online advertisers.

Which ones do you think they pay attention to?

Does your marketing budget reflect the reach of empowered customers? What are you doing to make it work for you? What are you doing to stop it from working against you?

a strategy IDEA for energizing your customers

The reason marketers generally haven’t harnessed these empowered consumers is simple. They know how to use concepts like reach, positioning, and key performance indicators to design marketing strategy and measure effectiveness. But they have no plan of attack for word of mouth, and no vocabulary to talk about it.

The other problem is that marketers work with masses: mass media and mass impressions. Empowered customers are individuals. Marketers don’t deal with individuals—customer service people do. Customer service is typically treated as a cost center, so service representatives serve customers as cheaply as possible. Unfortunately, that level of service is what creates the Dave Carrolls of the world.

Starting now, we want you to think about individuals as potential sources of marketing influence, either positive or negative. Your customer is a marketing channel. Every manager in a customer-facing department must therefore conceive of her job as to create more positive, and less negative, influence—and to do it as efficiently as possible. In Groundswell, we called this “energizing your customers.” It’s a new way to think about marketing, service, and customers.

How to do this? In a HERO-powered business, managers across all customer-facing departments need to connect with empowered customers. Here’s the four-step game plan with the mnemonic IDEA:

- Identify the mass influencers. Concentrate on the people most likely to spread messages about your company.

- Deliver groundswell customer service. Reach out through groundswell channels and serve these vocal and influential customers.

- Empower your customers with information, especially mobile information. Keep people happy by surrounding them with the information they need.

- Amplify your fans. Find the people who love you, and boost the impact they have on their peers.

In this chapter, we’ll concentrate on identifying mass influencers, but the rest is coming. Chapter 4 shows how to do groundswell customer service. Chapter 5 tells how to create mobile empowerment. And chapter 6 is your plan for fan marketing.

who are mass influencers?

In 2000, Malcolm Gladwell wrote an incredibly insightful book called The Tipping Point.10 He identified three groups of people who help spread trends. The first is a group called Connectors, people who know a wide variety of other folks through some sort of social connection. He also identified a group he called Mavens, who know stuff—these are the experts on wine, on fashion, on cars—whatever. (His third group, the Salesmen, don’t enter into the discussion in this chapter.)

Based on our research, these people have fascinating online analogs. Online Connectors are the people with lots of social network connections—people with a huge Twitter following, or a lot of Facebook friends, and who connect with their followers frequently. Online Mavens correspond to the people who post content online—they blog, or comment on blogs; they post in discussion forums; or they write reviews on sites like Amazon.com.

Using our survey, we examined these groups. We found out a few things that are very important for marketers and other customer-facing staffers to know. First of all, only a small subset of online connectors and online mavens accounts for nearly all of the influence; we call them mass influencers. And second, while mass influencers are a small percentage of the online consumers, there are still millions of them, so a one-person-at-a-time strategy isn’t appropriate. Make no mistake: mass influencers are a channel. You can let them say whatever they want, as Dave Carroll did, and then react. Or you can work proactively to get them sharing messages in line with your strategy.

Mass influencers come in two flavors: the Mass Connectors, who have the most influence within social networks, and the Mass Mavens, who have the most influence in content channels like blogs and discussion forums.

Mass Connectors live in the moment and connect with their friends

Who are the influential people on social networks? When we set out to answer this question, we suspected some sort of 80-20 rule would apply, in which 80 percent of the influence comes from 20 percent of the consumers.11

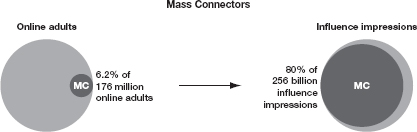

FIGURE 3-1

Mass Connectors account for 80 percent of the online influence in social networks

Base: U.S. online adults.

Source: Forrester’s North American Technographics Empowerment Online Survey, Q4 2009 (US).

It’s actually much more extreme than that.

Among social connectors, 80 percent of the impressions about products and services come from only 6.2 percent of the people online (see figure 3-1). That’s 11 million very connected people. These are the Mass Connectors.

Here’s why you should care about Mass Connectors. First, they are 11 million people who generate, collectively, 205 billion impressions annually on other people regarding products and services. That’s 18,600 impressions per Mass Connector per year. They have a lot of friends—the average Mass Connector has a total of 537 followers, friends, or connections in all of his or her social networks. (The rest of the social network members average 133.)

Social network impressions are fleeting, continuous, and viral. People retweet what others tweet, comment on others’ Facebook updates, get influenced by what their best professional colleagues say on LinkedIn, and pass those messages on. More importantly, they’re trusted, because they come from people’s friends. (If you have 537 friends, they won’t all be close friends, but even the acquaintances are more likely to pay attention to what you say than they would to a stranger.) So any strategy for tapping into this group needs to keep them close, not just once, but over time.

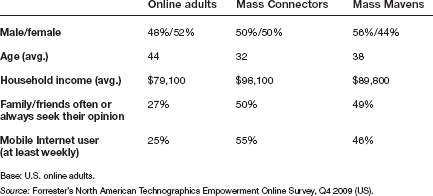

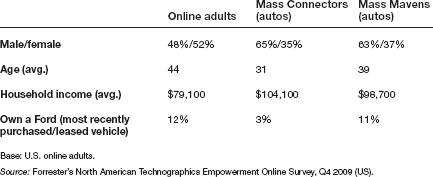

TABLE 3-1

Demographics of Mass Connectors and Mass Mavens

Let’s try to understand these people better.

Half are men and half are women (see table 3-1). They’re generally young, with an average age of thirty-two, and affluent, with an average household income of almost $100,000.

They think of themselves as influential—half of them say friends and family often seek their opinions. And 55 percent of them use the mobile Internet weekly, more than twice the population average.

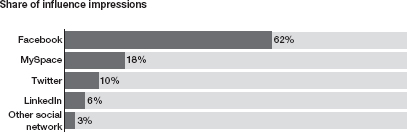

We can also tell you where they are expressing their influence. Facebook is huge. For every ten impressions created in social networks in the United States, six come from Facebook, two come from MySpace, one comes from Twitter, and one comes from some other site (see figure 3-2).

But when it comes to influence, the Mass Connectors tell only half the story. To get the other half, we need to look at the people who make a more lasting impression: the Mass Mavens.

Mass Mavens create more lasting influence

In contrast to Mass Connectors, who make their impressions on others within social networks, Mass Mavens contribute to blogs, discussion forums, and online reviews. They generally don’t know the people who see what they write, but their contributions can impress thousands of people over time. They’re the other source of influence in the groundswell. So let’s take a closer look at Mass Mavens.

FIGURE 3-2

Most of the influence impressions within social networks come from Facebook

Base: U.S. online adults.

Source: Forrester’s North American Technographics Empowerment Online Survey, Q4 2009 (US).

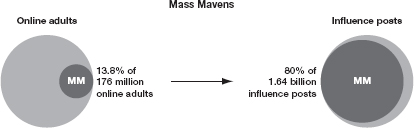

About 13.4 percent of the U.S. online population, or 24 million people, are Mass Mavens (see figure 3-3). (About 7 million people are in the overlap, being both Mass Mavens and Mass Connectors.) By definition, Mass Mavens generate 80 percent of the online posts (blog posts, blog comments, discussion forums, and reviews) regarding products and services, or about 1.31 billion total posts every year. That’s a lot of content about stuff you may be selling. And because Google is biased toward content with a lot of inbound links, like blogs and discussion forums, many of these posts may end up near the top of the search rankings for your products or product categories.

FIGURE 3-3

Mass Mavens account for 80 percent of the online posts about products and services

Base: U.S. online adults.

Source: Forrester’s North American Technographics Empowerment Online Survey, Q4 2009 (US).

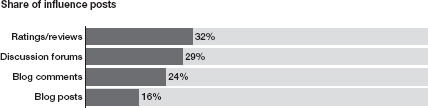

FIGURE 3-4

The majority of influence posts are on reviews and discussion forums

Base: U.S. online adults.

Source: Forrester’s North American Technographics Empowerment Online Survey, Q4 2009 (US).

In contrast to the Mass Connectors, the Mass Mavens are a little older, with an average age of thirty-eight, and not quite as rich, with an average income of $90,000. But like the Mass Connectors, they’re often consulted by their friends and families and very likely to use the mobile Web.

What sets these people apart is their productivity. They have opinions and they love to spread them. The average Mass Maven posts content about products and services fifty-four times per year. (Others, if they post at all, average only six posts per year.)

As it turns out, blogging gets all the publicity, but discussion forums and ratings and reviews account for over 60 percent of the posts about products and services (see figure 3-4). And Mass Mavens contribute more blog comments than blog posts. So if you’re monitoring online discussions about your products or using a service like Sysomos to do the monitoring for you, broaden your focus beyond blog posts, or you’ll miss five-sixths of the comments people make.

peer influence varies by product category

Both the Mass Connectors and the Mass Mavens must be part of any influence strategy.

To tap the Mass Connectors, you need content they’ll want to spread and link to, like viral videos or coupons. Comments from your own Twitter feeds and content from your Facebook pages are catnip for these types. You’ll also want to monitor what they’re saying, to make sure you can respond if there’s a problem (like Best Buy’s Coral Biegler did in chapter 1).

The Mass Mavens need to be handled a little differently. Because they write things like blog posts and reviews, they’re a little more thoughtful. Making available as much information as possible makes those posts easier to write. This is why your own corporate blog, clearly usable product pages, and information in media matter when it comes time to influence Mass Mavens.

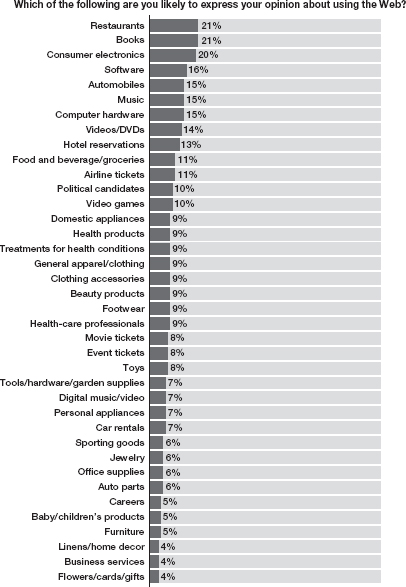

Of course, Mass Connectors and Mass Mavens don’t talk equally about all brands in all categories (see figure 3-5). For example, United Airlines would need to know that 11 percent of online consumers comment on airline tickets. Doing the same sort of peer influence analysis on airline influence that we did for the overall population, we can tell that when it comes to airline comments specifically, 0.9 percent of online adults are Mass Connectors and 2.2 percent are Mass Mavens. Clearly, a small number of people (like Dave Carroll) have an outsized amount of influence.

United has learned its lesson; it’s monitoring Twitter and has sixty thousand followers at @unitedairlines. (It turns out people who talk online about airlines are twice as likely to use Twitter as the general population.) It’s also monitoring airline forums like flyertalk.com and blogs that talk about airlines, to see what airline Mass Mavens may be saying.

But influence analysis isn’t just about defense—protecting your brand. It’s also about spreading positive word of mouth with mass influencers. That’s what Ford was aiming for when it launched the new Fiesta.

CASE STUDY

mass influencers for Ford

Here’s Scott Monty’s problem. Ford is an iconic American company. It’s been around a long time. People think they know what Ford is, and that image is old and stodgy. It doesn’t help that the other two big American car companies, GM and Chrysler, drove themselves into a ditch and needed government bailouts, tarnishing the American automotive industry’s image in the process.

FIGURE 3-5

What people share opinions about on the Web

Base: U.S. online adults.

Source: Forrester’s North American Technographics Empowerment Online Survey, Q4 2009 (US).

Ford has a potential hit on its hands with the new Fiesta. This shiny and innovative new model was the second most popular vehicle in Europe in 2009. The company needed a way to raise excitement in advance of the Fiesta’s U.S. launch in the summer of 2010.

So Scott and the team at Ford decided to manufacture some customers. Starting in 2009, they recruited a hundred people (including a few two-person teams) and gave them new Fiestas to drive around in. Daniel Grozdich is a working-class comedian in Malibu, California.12 Kristina Horner is a student from Seattle who travels around the country with her band. Taylor Barr and David Parsons are road-trippers from North Carolina who love social networks. Ford reviewed four thousand applications and picked the one hundred who seemed most likely to drive the car around and talk about it.

Want to see what they’re up to? Click on the live feed at www.fiestamovement.com. Between April and November of 2009, the fiesta movement’s YouTube videos racked up 7 million views. Seven hundred thousand saw the pictures they posted on Flickr. Four million saw their tweets. Ford had packaged up the energy of these new Fiesta drivers and harnessed it for marketing.

It worked. One hundred thousand people who went to fiestamovement.com signed up for a list to get more information. In December, the site began taking reservations. In one month, four thousand people signed up to buy a Fiesta.

Ford and Scott are not stopping now. In the next stage, volunteer Fiesta lovers will sign up in different parts of the country and channel the social activity by region. Because Scott knows that getting customers talking is the key to reinvigorating the image of Ford in America.

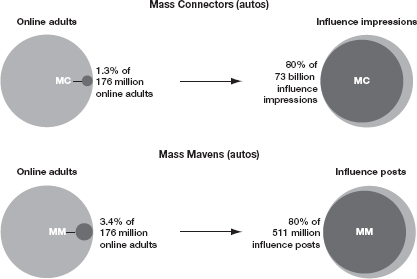

analyzing peer influence for Ford

Let’s look at customer influence from Ford’s point of view. Was the company’s strategy to generate word of mouth with customers the right one? Here’s where we can do an analysis of peer influence, not for general influencers, but for people who talk about cars.

First, let’s look at people who talk online about cars, which includes about 15 percent of the online population in the United States. Car influencers are more tightly concentrated than general influencers, but not quite as much as airline influencers. Mass Connectors for cars are 1.3 percent of the online population, and Mass Mavens for cars are 3.4 percent (see figure 3-6).

We can also look at the other side of influence—not just what people are saying, but what they are checking. People getting ready to buy a car are most likely to say they check online ratings, news sites, and friends’ opinions. Fewer say they check blogs or friends’ opinions on social network sites. But remember, this is a process that starts with awareness (that might come from a blog post found in a search, a friend’s tweet, or a news article written about fiestamovement.com). After the buyer becomes aware of the new Fiesta, she’ll research sources like ratings sites and news sites. Ford doesn’t want people not to check online information sites. It wants them to become aware of the Fiesta from as many sources as possible, and then check those sites.

FIGURE 3-6

Mass Mavens and Mass Connectors among car influencers

Base: U.S. online adults.

Source: Forrester’s North American Technographics Empowerment Online Survey, Q4 2009 (US).

Ford’s challenge is this: the people who talk about cars are well off and influential, but rarely own Fords (see table 3-2). With this analysis, and based on what Scott Monty told me—that the Fiesta is intended for a new, mostly younger type of customer—you can see why Fiesta Movement had to be designed the way it was. Ford had to create customers by letting them drive the cars for a while, to prime the pump and get the discussion going.

influence by generation

Is the groundswell a youth movement?

The social technology world is skewed toward the young, but not as much as it used to be. In 2009, 73 percent of online consumers aged 18 to 24 were using social content at least once a month.13 The corresponding number among consumers aged 45 to 54: 67 percent. Every year, the average age of social technology participants gets older.

TABLE 3-2

Demographics of Mass Connectors and Mass Mavens for auto purchases

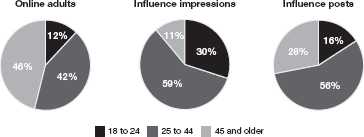

How does this translate to peer influence? We analyzed three groups of people online—18-to-24-year-old young adults, 25-to-44-year-old mainstream consumers, and 45-and-older mature consumers. Is one of these groups your market? Then you need to know these facts:

- Youths share disproportionately, but don’t dominate peer influence (see figure 3-7). While young adults are only 12 percent of the online population, they account for 30 percent of the influence impressions in social networks and 16 percent of the influence posts on blogs, forums, and reviews. The mainstream group of 25-to-44-year-old consumers generates more than half of the opinions about products and services in social environments of all kinds. And on blog, forum, and review sites, one in four opinions comes from consumers 45 and older.

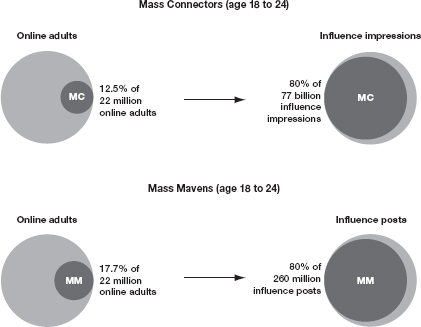

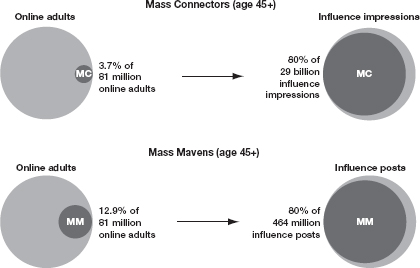

- We looked at these separate pools of influence to identify the mass influencers among them. Thirteen percent of young adults are Mass Connectors and 18 percent are Mass Mavens, so mass influencers among youth are broader and less concentrated than those in the general online population (see figure 3-8). But because there are fewer active participants among consumers forty-five and over, the Mass Mavens and Mass Connectors in this group are much more tightly defined: only 3.7 percent of online adults forty-five and over are Mass Connectors, and only 12.9 percent are Mass Mavens (see figure 3-9).

FIGURE 3-7

Young adults have disproportionate influence, especially in social networks

Base: U.S. online adults.

Source: Forrester’s North American Technographics Empowerment Online Survey, Q4 2009 (US).

FIGURE 3-8

Mass Connectors and Mass Mavens among online consumers age 18 to 24

Base: U.S. online adults age 18 to 24.

Source: Forrester’s North American Technographics Empowerment Online Survey, Q4 2009 (US).

- Looking at share of influence in social networks, Facebook is the biggest source of social network influence for all ages, but MySpace is second for young adults, while Twitter is second for mature consumers. On social content sites, young adults spend more effort on blogs and blog comments, while mature consumers are disproportionately likely to express their opinions on ratings sites.

FIGURE 3-9

Mass Connectors and Mass Mavens among adults 45 and over

Base: U.S. online adults age 45 and older.

Source: Forrester’s North American Technographics Empowerment Online Survey, Q4 2009 (US).

what peer influence means: customers matter more after the sale

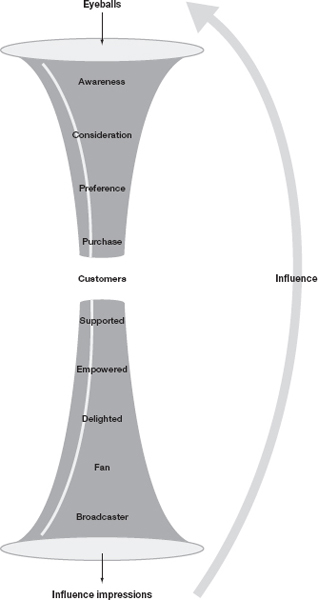

We all remember the marketing funnel from Marketing 101. In the funnel, people become aware of your company, consider its products, and then a few of them buy. (In more recent versions of the funnel, “loyalty” is at the narrow end.)

But now the mass influencers among your customers are broadcasting information about your products. The more empowered they get, the more influence they have. Increasingly, it’s their voice, not yours, that fellow buyers will hear.

This suggests a different view of the funnel, one in which sales is no longer the endpoint. Once you have sold a customer, good service will create happiness. Surrounding them with information will generate more touchpoints, and more reasons to feel good about your company. And enough outreach like this will create a customer who broadcasts your praises (see figure 3-10).14

FIGURE 3-10

In the new marketing funnel, influence begins after the sale

Let’s put this in context with a personal story. I (Josh) like to travel with my family. Hotels are too cramped for us. I like to rent a bigger place. So a few years ago, I found a Web site called rentvillas.com that has hundreds of houses throughout Europe. I arranged to rent a house in Italy.

Renting a house in another country can be nerve-wracking. To help you through the process, Rentvillas assigns you a personal travel advisor. Ours emailed me and then responded to questions about everything from local supermarkets to clothes dryers. She also sent us a map and a little 150-page self-published paperback by the company’s founder, Suzanne Pidduck, on living in Italy.

Our stay was delightful. After I returned, Suzanne emailed to suggest we rate the property on Rentvillas’ site. And after we’d done that, she suggested we rate the property on some other online travel sites, like ricksteves.com. The email was personal—it actually mentioned the minor problems we’d described with the Italian property. I later learned she sends hundreds of those emails every week.

Rentvillas manages two thousand rentals a year. I had already paid. And yet here the company was, treating me as important even though my next trip was certainly years off.

Rentvillas got my loyalty. But they got more, because I’m a Mass Maven. When they sent me the most deliciously tempting newsletter I’ve ever read, I blogged it.15 And when I wanted to hold up examples of companies that treat their customers like human beings, I interviewed Suzanne and blogged about it again. And here I am writing about it.

Rentvillas didn’t target me after carefully measuring my level of influence. They simply reached out to me, a customer, since they knew that my word of mouth, in person and online, would influence others. Just as they do with all the other customers.

Suzanne has recognized that the funnel doesn’t stop at the narrow end; it continues with personal service, surrounding the customer with information resources, and encouraging word of mouth. Customers are a marketing channel. Especially influential ones. Shiv Singh, vice president and global social media lead for Razorfish, calls this social influence marketing, or “having your customers create customers for you.”

If you think this philosophy can’t apply in big companies, you haven’t accounted for the employee HEROes who come up with solutions like Suzanne’s emails and Scott Monty’s Ford Fiesta Movement. You just need to find ways to encourage your staff to think this way.

In the next three chapters we describe those ways: delivering groundswell customer service, empowering customers with information, and amplifying word of mouth (the D, E, and A in IDEA). And we show how to do it efficiently, regardless of the size of your company.