CHAPTER

6

Turning Strategy into Reality

Putting strategic initiatives into effect in organizations is like turning an ocean liner at full steam. Although the captain’s command may echo loud and clear, and even if the turning procedure is underway, no direction change is apparent for the first few moments. The inertia of these giant vessels, measuring hundreds of yards in length, is so great that a quick response is out of the question. It takes planning ahead and allowance for reaction time to make the right change in an ocean liner’s course.

This same challenge permeates the corporate world. While top decision makers may mandate a given strategy, overcoming the business-as-usual inertia takes time. Allowing for the inertia-related time lag is crucial for the success of strategic projects. So the time lapse for the course-changing process has to be built into the components of Enterprise Project Governance. This chapter pinpoints the policies and practices to be defined in EPG to ensure that strategies are duly implemented and translated into results.

The starting point is the strategy itself. This assumes that a solid portrait of the desired results exists, formalized in terms of strategic initiatives. That overall strategy then acts as the bedrock that sustains the implementation of the projects designed to paint the picture visualized by the organization’s strategists. When the strategies are swiftly and effectively put into place, the odds are good that they will bear benefits. A great strategy, nimbly implemented, guarantees success and generates benefits, fulfillment, and rewards. The actual success rates for implementing strategies, however, leave room for improvement. Consider a few dismal numbers:

![]() A 2004 survey by The Economist of 276 senior operating executives found that 57 percent of the companies had been unsuccessful in executing strategic initiatives over the previous three years.1

A 2004 survey by The Economist of 276 senior operating executives found that 57 percent of the companies had been unsuccessful in executing strategic initiatives over the previous three years.1

![]() In a 2006 survey of more than 1,500 executives by the American Management Association and the Human Resource Institute, only 3 percent of respondents rated their companies as very successful at executing corporate strategies, whereas 62 percent described their organizations as mediocre or worse.2

In a 2006 survey of more than 1,500 executives by the American Management Association and the Human Resource Institute, only 3 percent of respondents rated their companies as very successful at executing corporate strategies, whereas 62 percent described their organizations as mediocre or worse.2

![]() In 2007, the Conference Board asked 700 executives to list their top 10 challenges. Excellence in execution and consistent execution of strategy by top management ranked first and third, respectively, as the greatest concerns. Clearly, the ability to transform strategic plans into action is a universal concern.3

In 2007, the Conference Board asked 700 executives to list their top 10 challenges. Excellence in execution and consistent execution of strategy by top management ranked first and third, respectively, as the greatest concerns. Clearly, the ability to transform strategic plans into action is a universal concern.3

Therefore, even an inspired strategy poorly implemented may spell failure. For instance, a beautifully balanced portfolio is of little use if its projects run helter-skelter, overtop their budgets, and without the intended outcomes. On the other hand, a superbly managed project that finishes out of synch may inadvertently sabotage a well-designed strategic campaign. For instance, if the strategy is to be first-to-market, and if the execution phase lacks agility, then the strategy might not work at all. Aside from schedule overruns, other barriers can roadblock a good strategy. Rampaging costs make return-on-investment figures look discouraging. Quality glitches are another source of sabotage for even the most enlightened strategies.4

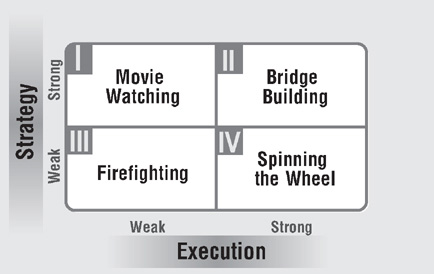

Four Views for Getting Things Done

The enduring success of organizations depends on two dimensions: strategy (decisions on the paths to follow) and execution (getting things done along the pathways). Expanding on the classic combinations of strategy versus execution presented in Chapter 5, Exhibit 6-1 shows how these dimensions unfold into the four performance quadrants.

Each quadrant has specific performance characteristics:

![]() Quadrant I—Movie Watching. In this quadrant, a business has a strong strategy poorly executed, which means that the organization will stay where it is. The strategy is like a powerful creative movie but with an audience passively watching it without being motivated. Although a clear vision is established, the organization is incapable of moving in that direction. The dreams are not translated into the desired outcomes and benefits.

Quadrant I—Movie Watching. In this quadrant, a business has a strong strategy poorly executed, which means that the organization will stay where it is. The strategy is like a powerful creative movie but with an audience passively watching it without being motivated. Although a clear vision is established, the organization is incapable of moving in that direction. The dreams are not translated into the desired outcomes and benefits.

![]() Quadrant II—Bridge Building. Quadrant II requires a disciplined organization, one that addresses the needs of today yet builds for tomorrow. In this quadrant, good strategy is matched with good execution. This means consistently maintaining the right strategies along with agile execution of the strategic projects. Richard Lepsinger, author of Closing the Execution Gap, says that five bridges help people traverse the execution gap: (1) the ability to manage change, (2) a structure that supports execution, (3) employee involvement in decision making, (4) alignment between leader actions and company values and priorities, and (5) company-wide coordination and cooperation. Organizations in this quadrant are capable of correctly building the bridges between strategy and execution.

Quadrant II—Bridge Building. Quadrant II requires a disciplined organization, one that addresses the needs of today yet builds for tomorrow. In this quadrant, good strategy is matched with good execution. This means consistently maintaining the right strategies along with agile execution of the strategic projects. Richard Lepsinger, author of Closing the Execution Gap, says that five bridges help people traverse the execution gap: (1) the ability to manage change, (2) a structure that supports execution, (3) employee involvement in decision making, (4) alignment between leader actions and company values and priorities, and (5) company-wide coordination and cooperation. Organizations in this quadrant are capable of correctly building the bridges between strategy and execution.

Exhibit 6-1. Performance Quadrants

![]() Quadrant III—Firefighting. Companies operating in this quadrant are focused on operations, using poor processes and involving management and employees who are overworked, confused, and feeling hopeless due to the critical issues without resolution. Robert Kaplan, author of several books on the Balanced Scorecard, says, “Though executives may formulate an excellent strategy, it easily fades from memory as the organization tackles day-to-day operations issues.” He adds that this creates a situation of “fighting fires making employees react to issues within the business rather than managing the business itself.” Since strategy is weak and the execution is chaotic, the priority is for resolving the always urgent and present issues, leaving the future for a tomorrow that never comes.

Quadrant III—Firefighting. Companies operating in this quadrant are focused on operations, using poor processes and involving management and employees who are overworked, confused, and feeling hopeless due to the critical issues without resolution. Robert Kaplan, author of several books on the Balanced Scorecard, says, “Though executives may formulate an excellent strategy, it easily fades from memory as the organization tackles day-to-day operations issues.” He adds that this creates a situation of “fighting fires making employees react to issues within the business rather than managing the business itself.” Since strategy is weak and the execution is chaotic, the priority is for resolving the always urgent and present issues, leaving the future for a tomorrow that never comes.

![]() Quadrant IV—Spinning the Wheel. A business without a strategy, or with a bad one, but good at execution may do well for a while, but sooner or later it will fall victim to a competitor or the ever mutant environment. However, no amount of operational excellence can prevent failure stemming from poor decisions and a bad strategy. For firms that want to remain competitive in the marketplace, operational excellence is necessary but not sufficient. Such firms may go under or become targets for takeovers.

Quadrant IV—Spinning the Wheel. A business without a strategy, or with a bad one, but good at execution may do well for a while, but sooner or later it will fall victim to a competitor or the ever mutant environment. However, no amount of operational excellence can prevent failure stemming from poor decisions and a bad strategy. For firms that want to remain competitive in the marketplace, operational excellence is necessary but not sufficient. Such firms may go under or become targets for takeovers.

Moving Around the Quadrants

Ice cream accompaniments manufacturer Askey’s was founded in 1910. The business was sold to Kellogg’s, the American food manufacturing giant, in 1965. Under the new ownership, Askey’s was used solely as a manufacturing site, with support services being run from Kellogg’s U.K. head office. During this period, the factory concentrated on the mass production of a limited range of standard cones and wafers sold to ice cream parlors and kiosks, ice cream vans, and other outside caterers. However, through the 1980s, the market took a turn, and sales through supermarkets became the headliner. By the 1990s, the vast majority of Askey’s products were channeled through the major supermarkets. Sales to the catering trade and ice cream vendors were diminishing. Under the relentless downward price pressure exerted by the supermarkets, profitability plummeted. Nonetheless, Askey’s retained its position as the largest British manufacturer of ice cream accompaniments, but little effort was put into articulating a strategy that could create new products or geographic expansion. Askey’s was merely spinning the wheel.

In 1995, Askey’s was acquired by two experienced food industry executives, financed by venture capitalists. The new owners set about extending the product range. Though this takeover seemingly heralded a fresh start for the firm after a period of underinvestment, it wasn’t long before cracks appeared. A new strategy was tried based on the creation of new products, but it resulted only in short-term profit, which was not sustainable over the long run due to the lack of investments. The company entered into the firefighting quadrant because of the expansion without a clear articulated strategy. After more than a decade of steady firefighting, the business was bought out again.

In 2004, Askey’s was sold to Silver Spoon, Britain’s largest sugar and sweetener producer. The company’s strategy was to continue expanding the business through exploring new markets, expanding existing ones, and new product development. This resulted in a jump up to an 80 percent share of the U.K. retail market for ice cream peripherals and a significant share of the market for restaurants, cafés, and ice cream vans. The company thus moved on to the bridge-building quadrant.

In the years since 1910, Askey’s moved through three of the four quadrants, lacking only movie watching, which depicts a good strategy poorly implemented. Over time, companies naturally pass through periods of change regarding the relationship of strategy to execution, as they strive for the ideal. A vigorous strategy-execution balance is the obvious pathway for achieving healthy organizations. Strong strategies, coupled with great execution, represent the magic formula for reaching the organizational nirvana suggested in quadrant II.

While this balance is sometimes attained by companies for periods of time, market trends, technological breakthroughs, and shifts in the worldwide economy invariably bump even the most effective organizations off course from time to time. An example follows of how a highly successful industry over the years comes to terms with strategies and execution during dramatically changing times.

Big Pharma: An Industry Faced with Challenges

Competitive and technological changes in the pharmaceutical industry are reshaping the business.5 No fewer than nine of the pharmaceutical industry’s 10 biggest blockbusters go off patent and face low-cost generic competition by 2016. This has a gigantic impact on big pharma, as the large pharmaceutical companies are called. By some estimates, expiring prescription drug patents will cost the pharmaceutical industry over US$50 billion in revenues by 2020. These pressures strain the traditional, vertically integrated business model of big pharma. Best sellers like Pfizer’s cholesterol-lowering Lipitor, the world’s most prescribed medicine, lost patent protection in 2011. The drug is responsible for 20 percent of the largest big pharma’s annual revenue. As cholesterol drugs go off patent, a new stream of high cholesterol–controlling drugs enters the market. Yet the question arises: Will they evolve fast enough to offset the losses from generics?

A survey of global pharmaceutical executives by Germany’s Roland Berger Strategy Consultants,6 with participating companies covering 40 percent of global pharmaceutical revenues and including seven out of the global top 10 players, found that 65 percent of those polled said the sector faced a “strategic crisis.” Nearly half of those questioned agreed that current investments in research and development would yield a negative return. Changing health care environments, budget pressures, challenging market access, and massive patent expirations caused a major upset in the traditional business model, which has focused exclusively on high-margin and patent-protected innovative medicine.

As a result, the industry began reshaping and altering the way business was conducted—from R&D to sales and marketing. Big pharma faces the challenge of improving individual patient outcomes and health outcome predictability through the tailoring of treatments. For that to happen, a move is required from the present model of one size fits all with lower predictability of outcomes to a more tailored approach stratifying populations and optimizing outcomes based on biomarkers as a step to targeted therapy.

To meet the challenge, drug giant GSK (GlaxoSmithKline) established the following strategies aimed at increasing growth, reducing risk, and improving long-term financial performance:7

![]() Grow a diversified global business.

Grow a diversified global business.

![]() Deliver more products of value.

Deliver more products of value.

![]() Simplify GSK’s operating model.

Simplify GSK’s operating model.

![]() GSK’s corporate structure includes a position of chief strategy officer, whose task is to formulate appropriate strategies based on market information and input from stakeholders and to interface with other areas to ensure that the strategies become reality.

GSK’s corporate structure includes a position of chief strategy officer, whose task is to formulate appropriate strategies based on market information and input from stakeholders and to interface with other areas to ensure that the strategies become reality.

To make the complementary strategies become reality, GSK counts on a solid set of Enterprise Project Governance principles and structures. For starters, a corporate-level PMO is part of the CEO’s office and is charged with tracking strategic projects and seeing that they are appropriately supported. Business units also have their own PMOs and basic project management methodology and support are part of the GSK organization.

Under the emerging scenario, corporate strategies are aimed less at milking blockbuster discoveries and more at a market mix that involves both organic growth and acquisitions in areas such as biotechnology, dermatology, oncology, and generics. This creates a fragmented portfolio of projects and a need for an enterprise-wide project culture capable of managing projects at strategic, tactical, and operational levels. Change management, marketing, and organizational restructuring projects are particularly relevant in the increasingly dynamic scenario.

At GSK, manufacturing and R&D projects continue to be managed under a traditional portfolio of projects. Increased attention, however, is given to the broad array of the emerging organizational, administrative, and commercial projects demanded by the changing marketplace. Initiatives called “critical business drivers” (those that strongly affect business outcomes), are labeled as strategic projects and given high priority. Whereas in a given region such as Latin America, comprised of 37 countries, hundreds of individual projects may vie for budget resources, as few as seven projects may be chosen for high-profile attention and tracking at an executive level. Other approved tactical and operational projects are dealt with at the country level.

Big pharma is a striking example of industries impacted by sweeping changes in the marketplace. Invariably, major marketplace turmoil calls for an overhaul not only in strategic direction, but also in transforming those strategies into reality as quickly as possible. When the right strategies are done right and put into place on a timely basis, good things happen for the organization. Yet if the organization lacks both project management expertise and the drive to turn the strategies swiftly into reality, great strategies are of little avail.

How to Transform Strategies into Reality

A principal function of Enterprise Project Governance is to make sure that policies are defined and put into place for the right composition of projects to be managed effectively. Turning strategies into results requires a three-pronged approach once the strategic projects have been selected and prioritized, as outlined in Chapter 5. There’s no off-the-shelf package for managing these strategic projects; a customized approach is called for.

Here are key management actions for making sure the portfolio of projects spawns the benefits aspired to by corporate decision makers:8

![]() Balance the overall portfolio.

Balance the overall portfolio.

![]() Use program management to group and coordinate related projects.

Use program management to group and coordinate related projects.

![]() Apply stage gate tracking for individual strategic projects.

Apply stage gate tracking for individual strategic projects.

![]() Apply classic project management principles.

Apply classic project management principles.

![]() Analyze benefits management.

Analyze benefits management.

Keeping the Portfolio Balanced

Chapter 5 sums up the challenges of forming and balancing project portfolios. This balance is vital for successfully implementing the organization’s strategy. The right design of project mix sets the stage for turning strategy into results. Yet portfolio design and planning are only part of the equation. Other factors are crucial to optimize desired results. For instance, keeping the portfolio balanced over time is as important as starting off right. For that equilibrium to remain, periodic reviews are required. These may happen semiannually, quarterly, or as often as monthly depending on organizational dynamics.

Portfolio reviews are worth the effort because they force upper management to size up benefits over time. They are fruitful when proactive decisions are made, such as accelerating projects, putting some on hold, and aborting others. Here are issues that merit reflection during a project portfolio review session:

![]() Balance between short-term and long-term projects

Balance between short-term and long-term projects

![]() Budget adjustments as time progresses

Budget adjustments as time progresses

![]() Balance between risks and rewards

Balance between risks and rewards

![]() Cash flow implications

Cash flow implications

![]() Operational impacts of completed projects

Operational impacts of completed projects

Portfolio reviews take place in various organizational settings. For instance:

![]() Strategic PMO. Typically, the scope of strategic PMOs includes running periodic portfolio alignment reviews. This involves the participation of appropriate stakeholders, who may vary depending on the projects under review.

Strategic PMO. Typically, the scope of strategic PMOs includes running periodic portfolio alignment reviews. This involves the participation of appropriate stakeholders, who may vary depending on the projects under review.

![]() Portfolio Management Committee. Another option is for the portfolio reviews to be carried out by a committee convened for this purpose.

Portfolio Management Committee. Another option is for the portfolio reviews to be carried out by a committee convened for this purpose.

![]() Executive Committee. Ultimately, the review may land on the agenda of an executive committee, tasked with overall management responsibilities.

Executive Committee. Ultimately, the review may land on the agenda of an executive committee, tasked with overall management responsibilities.

Where the review takes place is not important as long as it is effective, touches on the right topics, and results in proactive decision making. It is ultimately the responsibility of EPG to make sure that firm policies are fixed so that effective project portfolio reviews are carried out periodically.

Keeping Related Projects Aligned: Program Management

The continuous alignment of related projects can be guaranteed by gathering them under the umbrella of an overarching program. Program management is designed to direct interrelated projects toward achieving strategic results. The links between projects in a given program vary from being tightly to loosely connected. Such is the case of the overall space exploration program managed by NASA, which includes specific programs of interconnected projects aimed at earth-related studies, manned space flight, planets and asteroids, science and technology, stars and the cosmos, and the sun. Each of these groups congregates interrelated projects, and the programs themselves are also loosely linked because they are all space related.

Keeping Individual Projects on Course: Stage Gates

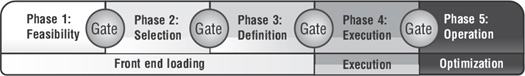

Stage gates are check points along a project’s pathway to completion, aimed at ensuring that the previous stage has been completed and that all is clear to move on to the next stage. These gates help in shining a light on status, in sizing up the business situation, and in evaluating assigned resources. Stage gates provide decision makers with the information to review status in the light of new developments.

Various names are used for this checkpoint concept, including stage gates, review points, gates, design reviews, and project gates. The terminology used for capital expenditure projects like offshore oil rigs, for instance, identifies three major gates: FEL 1, FEL 2, and FEL 3. FEL means “front end loading,” referring to early rites of passage prior to the outlay of major investments, thus optimizing design and avoiding rework and unnecessary costs, as shown in Exhibit 6-2.

Exhibit 6-2. FEL in the Stage Gate Process

In this model, FEL 1 refers to kickoff activities such as project charter development and initial feasibility. FEL 2 embodies the preliminary scope for equipment design, layout, schedule, and estimates. Finally, FEL 3 includes detailed information about major equipment specifications, final estimate, project execution plan, preliminary 3-D model, and equipment lists.

The FEL approach is also known as preproject planning. No matter what the moniker, the stage gate technique provides powerful input toward reducing uncertainty, so that cost–time–quality parameters are met to the satisfaction of the sponsoring organization. In these early stages of major projects, optimizing tools such as VIPs (value-improving practices, which use techniques like value engineering) are also instrumental in ensuring effective stage gating.

In some cases, only three gates are appropriate, yet as many as six might make sense in other settings, with the number left to the discretion of the sponsor or to best practices in the specific industry. Here are factors that influence the decision regarding the number of gates:

![]() The stability of the business case as related to changes in the strategic environment

The stability of the business case as related to changes in the strategic environment

![]() The empowerment appropriate for the project manager to make decisions that are aligned with the strategy

The empowerment appropriate for the project manager to make decisions that are aligned with the strategy

![]() The nature of the project and the extent to which periodic external review is appropriate

The nature of the project and the extent to which periodic external review is appropriate

![]() The quality of metrics available to both the project team and the sponsor

The quality of metrics available to both the project team and the sponsor

Effective Enterprise Project Governance policies do not specify the number of stages or their content, yet they do determine the use of a stage gate approach for making sure that projects are strategically monitored.

Doing Individual Projects Right: Methodologies, Best Practices, and Standards

Making strategies happen depends on the implementation of the projects that unfold from the strategies. That implementation requires focus on completing enterprises and projects within cost parameters, time constraints, and quality specifications. For that to occur, the best practices of project management come into play.

Since a project approach is needed to make the leap from strategy to results, it makes sense to draw from the accumulated know-how of the project management profession. It is the responsibility of Enterprise Project Governance to make sure the fundamentals of project management are defined and in place in the organization.

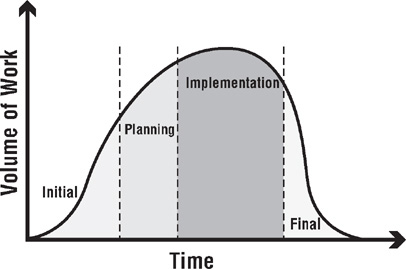

Projects are carried out over a time frame, known as the project life cycle. This is true for projects of all natures, whether strategic, operational, or innovative. Since projects, like people, are finite by definition, they are designed to be born and to be terminated. Projects also live a life and go through distinct phases. Exhibit 6-3 shows an example of a life cycle.

Exhibit 6-3. Example of a Project Life Cycle

Here are pertinent questions for sponsors and reviewers to raise throughout the project life cycle:

Preproject Phase

![]() Does the project meet company standards in terms of profitability or return on investment? Are resources available to carry out the project?

Does the project meet company standards in terms of profitability or return on investment? Are resources available to carry out the project?

![]() Are the premises and numbers used in the feasibility study valid?

Are the premises and numbers used in the feasibility study valid?

Concept Phase

![]() Does a project charter define the project mission and primary objectives?

Does a project charter define the project mission and primary objectives?

![]() Is the overall scope of the project clearly defined?

Is the overall scope of the project clearly defined?

![]() Is all the information needed for the project to proceed available and organized?

Is all the information needed for the project to proceed available and organized?

![]() Have the design assumptions been validated?

Have the design assumptions been validated?

![]() Have the client requirements been formally confirmed?

Have the client requirements been formally confirmed?

![]() Has a macro risk assessment been carried out?

Has a macro risk assessment been carried out?

![]() Are key stakeholders involved?

Are key stakeholders involved?

![]() How about the project manager? Does he need more support or on-the-job training? Or could she use additional guidance during a given phase?

How about the project manager? Does he need more support or on-the-job training? Or could she use additional guidance during a given phase?

![]() Has formal project kickoff been planned? What format is planned? Meeting? Workshop?

Has formal project kickoff been planned? What format is planned? Meeting? Workshop?

Planning Phase

![]() Has a quality assurance plan been developed?

Has a quality assurance plan been developed?

![]() Are project management and implementation strategies and methodologies in place?

Are project management and implementation strategies and methodologies in place?

![]() Have project risks been identified, quantified, and risk responses identified?

Have project risks been identified, quantified, and risk responses identified?

![]() Are systems for document management, activity scheduling and tracking, procurement management, estimating, budgeting, and cost control in place?

Are systems for document management, activity scheduling and tracking, procurement management, estimating, budgeting, and cost control in place?

![]() Have the systems been debugged, and is the staff competent at operating them?

Have the systems been debugged, and is the staff competent at operating them?

![]() Has an overall, technically oriented detailed project plan been developed? (What is to be done on the project and how will the work be performed?)

Has an overall, technically oriented detailed project plan been developed? (What is to be done on the project and how will the work be performed?)

![]() Has a project management plan been developed (how will the project be managed)?

Has a project management plan been developed (how will the project be managed)?

![]() Is there a stakeholder management plan?

Is there a stakeholder management plan?

![]() Have statements of work (SOWs) been written for the work packages?

Have statements of work (SOWs) been written for the work packages?

![]() Has the project communications plan been developed?

Has the project communications plan been developed?

![]() Have the meeting and reporting criteria been developed?

Have the meeting and reporting criteria been developed?

Implementation Phase

![]() Are regular tracking meetings taking place?

Are regular tracking meetings taking place?

![]() Is change management being formally managed?

Is change management being formally managed?

![]() Is decision making proactive and solution oriented?

Is decision making proactive and solution oriented?

Final Phase

![]() Have project closeout procedures been developed, and are they in place?

Have project closeout procedures been developed, and are they in place?

![]() Has a transition plan (from project completion to operation phase) been prepared, and is it being followed?

Has a transition plan (from project completion to operation phase) been prepared, and is it being followed?

Postproject Phase

![]() What was done right on the project, and what needs improvement on the next one?

What was done right on the project, and what needs improvement on the next one?

![]() How did the project size up with other comparable projects within or outside the company?

How did the project size up with other comparable projects within or outside the company?

![]() What lessons learned need to be shared with others in the company?

What lessons learned need to be shared with others in the company?

![]() How can project results be used for marketing and promotional purposes?

How can project results be used for marketing and promotional purposes?

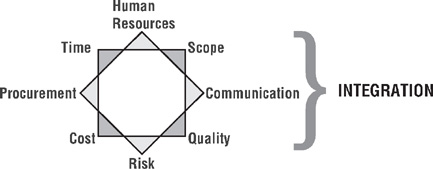

Views of Project Management from Professional Associations

The essence of project management was traditionally represented by a triangle, depicting the need to manage time, cost, and quality. These core areas have long since morphed into a square, depicting quadruple constraints, with the addition of scope management because scope is so tightly intertwined with the elements of the classic triangle. So time, cost, quality, and scope are the pillars for turning strategic projects into results.

PMI

These four basic areas have since evolved into nine knowledge areas as outlined by PMI: management of time, scope, quality, cost, risk, communication, procurement, human resources, and integration.9 All of these areas have to be managed to make things work. A slipup in any area is enough to start a domino effect that can go crashing into all other areas. For instance, a communication glitch in the procurement cycle might set off an unscheduled time delay that affects quality and amasses a cost overrun. This may put the project in danger and have a strong impact on human resources. So intimate connections exist among all the areas. The PMI model is dynamic and evolves as new perceptions are recognized. For instance, the topic of project stakeholder management is gaining increased attention in the literature as researchers and practitioners perceive the substantial impact it has on the success or failure of projects. Exhibit 6-4 shows the knowledge areas as defined by PMI.

Exhibit 6-4. Integrating the Basic Project Management Areas

International Project Management Association

The International Project Management Association (IPMA) represents more than 50 project management associations from all continents and offers another basic model. The IPMA Competence Baseline (ICB)10 is the basis for a certification system and serves as a standard for practitioners and stakeholders. This model assumes that professionals must have competency in three basic areas: behavioral, technical, and contextual.

Standards Related to Executing Projects

Over the years, PMI has developed a library of global standards. Five themes reflect the expansive nature of the project management profession: projects, programs, people, organizations, and profession. IPMA also periodically updates its competence baseline standard. The U.K. Office of Government Commerce (OGC) also provides policy standards and guidance on best practice in procurement, projects, and estate management, and it monitors and challenges departments’ performance against these standards, grounded in an evidence base of information and assurance. Their publications include the themes of portfolio, programs, and projects as well as the widely accepted Prince 2 methodology.

As project management continues to grow and gain recognition globally, since 2006 the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has been developing Standard 21500, Guidance on Project Management, with final delivery expected by 2013. Over 30 countries participate in its development.

Keeping Benefits Realization on Track: Using the Why-How Framework

Execution is the crucial step in realizing benefits. Execution can free up resources or transform the organizational portfolio into a never-ending story of great goals. Execution is the interface between strategy carriers, programs and projects, and operations. Failure to achieve successful execution leaves strategies incomplete and resources unavailable for other projects. Successful execution requires strong sponsorship, coordination of commissioning and testing, attention to managing change produced by projects’ outputs, and feedback from operations to the portfolio team and from them to the strategic planners.

An Implementation Strategy in Practice

The Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), based in Alexandria, faced major challenges in implementing its strategy to construct a US$1.4 billion high-occupancy toll lane infrastructure project, which started in 2007.11 Here was the scenario:

![]() The project was structured as a design-build public-private partnership (PPP) between VDOT, Fluor-Lane, partnering contractors, and Transurban, a toll road developer and investor.

The project was structured as a design-build public-private partnership (PPP) between VDOT, Fluor-Lane, partnering contractors, and Transurban, a toll road developer and investor.

![]() It was situated in a congested travel corridor around Washington, D.C.

It was situated in a congested travel corridor around Washington, D.C.

![]() The work involved new construction, replacing aging infrastructure, relocating houses, and adding toll lanes.

The work involved new construction, replacing aging infrastructure, relocating houses, and adding toll lanes.

![]() The economy was in a downturn.

The economy was in a downturn.

![]() The project involved 300 contractors, working at off hours and weekends.

The project involved 300 contractors, working at off hours and weekends.

The governance of the project was mandated by the State of Virginia’s Public-Private Transportation Act of 1995, a legislative framework enabling the Virginia Department of Transportation to enter into agreements authorizing private sector entities to develop and/or operate transportation facilities. The governing criteria established by the act include policies related to quality control, an independent review panel, state transportation board recommendations, the selection of detailed proposals, negotiations, and final legal review of agreement.

Under these governing guidelines, the project was managed using classic project management techniques such as planning, organization, and control. The knowledge areas of project management also came into play, including the effective management of scope, time, cost, quality, procurement, human resources, communications, risk, and integration. Since things do not always come out as planned, implementing strategies called for adjustment when things swung off course. This was the case for VDOT.

VDOT’s strategy was to carry out the billion-dollar-plus project with minimum disruption of traffic under the governance umbrella of a design-build public-private partnership. That said, the question became how to make it happen. The design-build format was new for the state, as was the public-private partnership model. Although turning strategy into reality is, in principle, a matter of applying the basics of project management, twists and turns are normal along the pathway, as revealed on the VDOT project.

As construction started at the end of 2007, it became apparent that a basic piece in the project governance was missing. While VDOT became focused on evaluating every contract package, the Fluor-Lane team became increasingly anxious to get the bids out, and this created tension early on between the partners. To meet the ambitious time lines fixed for the project, VDOT didn’t have the manpower or expertise to evaluate and approve the bid packages as required. As a result, due to the lack of approved designs, some contractors found themselves on site without the drawings to proceed. This meant scrambling for alternative ways to utilize the labor force until the bidding procedure could be completed.

To resolve this, VDOT brought in an additional player to help meet the demands. ATCS CH2M Hill, a joint venture between two U.S.-based engineering companies, was contracted to take on the responsibility for managing the mega project, acting as the technical manager and administrative arm. ATCS CH2M Hill consequently became an additional stakeholder in the project’s governance structure. The joint venture’s major challenge was to strike a balance between the competing needs for appropriate oversight and urgent action.

Turning strategies into reality calls for applying the basics of project management and then going beyond. Constant evaluation and fine-tuning are also parts of the formula for making strategies actually happen. In the case of the VDOT mega project, a major issue of governance was overlooked in the beginning and ended up causing turmoil. Although the act established a solid base for governance, a basic structural link was missing with respect to the hands-on management of the project. Once the governance issue was fixed by bringing in an engineering consortium to act as project managers in support of the client, the project was pulled back on course.

Bridge Building

Over the years, people have been struggling with how to create a model for successful strategy implementation. Getting from strategy to execution requires a coherent and reinforcing set of supporting practices and structures. One model that has persisted is the McKinsey 7S model, which involves seven interdependent factors, which are categorized as either hard elements (strategy, structure, and systems) or soft elements (shared values, skills, style, and staff). The model is based on the theory that, for an organization to perform well, these seven elements need to be aligned and mutually reinforcing.

The 7S model is adequate for analyzing a current situation and a proposed future situation and for identifying gaps and inconsistencies that must be addressed in order to make the journey successful. It’s then a question of adjusting the elements to ensure that the organization works effectively to reach the desired endpoint. Let’s look at each of the elements:

![]() Strategy. The integrated vision and direction of the company, as well as the manner in which it derives, articulates, communicates, and implements that vision to maintain and build competitive advantage.

Strategy. The integrated vision and direction of the company, as well as the manner in which it derives, articulates, communicates, and implements that vision to maintain and build competitive advantage.

![]() Structure. How the company is organized to execute strategy, including the policies and procedures that govern how the organization acts within itself and within its environment, as well as the way who reports to whom.

Structure. How the company is organized to execute strategy, including the policies and procedures that govern how the organization acts within itself and within its environment, as well as the way who reports to whom.

![]() Systems. The decision-making systems within the organization that can range from management intuition, to manual policies and procedures, to structured computer systems.

Systems. The decision-making systems within the organization that can range from management intuition, to manual policies and procedures, to structured computer systems.

![]() Shared Values. The principles adopted by the company to guide its style and behavior. (The values and desired behavior must be communicated to and embraced by the entire organization.)

Shared Values. The principles adopted by the company to guide its style and behavior. (The values and desired behavior must be communicated to and embraced by the entire organization.)

![]() Style. The shared and common way of thinking and behaving, involving the organization culture and leadership style and reflecting the manner in which the company interacts with stakeholders, customers, and regulators.

Style. The shared and common way of thinking and behaving, involving the organization culture and leadership style and reflecting the manner in which the company interacts with stakeholders, customers, and regulators.

![]() Staff. The employees and their general capabilities. (Effective people management is about creating the right workforce to achieve the desired objectives. It means that the company has hired able people, trained them well, and assigned them to the right jobs.)

Staff. The employees and their general capabilities. (Effective people management is about creating the right workforce to achieve the desired objectives. It means that the company has hired able people, trained them well, and assigned them to the right jobs.)

![]() Skills. The actual skills and competencies of the employees working for the company. (It refers to the fact that employees have the skills needed to carry out the company’s strategy.)

Skills. The actual skills and competencies of the employees working for the company. (It refers to the fact that employees have the skills needed to carry out the company’s strategy.)

All this may appear simple, but it is not. The main message is that a multiplicity of factors influence an organization’s ability to change. And a crucial point is that organizations don’t always get the people side of implementation right (shared values, style, staff, and skills) and their reaction to the change involved.

In reality, bridging the strategy execution gap requires a program to manage all the projects and initiatives to accomplish the expected results, all under the EPG oversight framework.

Conclusions

The chapter encompasses approaches for implementing projects coherently with corporate strategy. Since it takes projects to implement strategies, the basics of project management are outlined. Three approaches are shown to ensure the alignment of projects and portfolio with the organization’s strategies: (1) project portfolio balancing, (2) program management, and (3) stage gate reviews. Also, establishing strong strategy associated with strong execution (bridge building) requires a set of integrated and reinforcing practices. Effective EPG prescribes policies to ensure that the practices outlined in this chapter are ingrained in the project management culture of the organization. The implementation of strategies calls for applying the basics of project management, beginning with project governance, and then customizing portfolio, program, and project management to fit the organization.