CHAPTER

8

Stakeholder Management and

the Pivotal Role of the Sponsor

Stakeholder management is a basic cornerstone in Enterprise Project Governance. It deals with organizational relationship issues and includes interfacing approaches such as power, politics, and influence. Special interests, hidden agendas, negotiations, and interpersonal conflicts also come into play in stakeholder management. Although sometimes perceived as a collection of soft behavioral methods, in fact, stakeholder management often calls for hard-knuckled action to effectively deal with the issues.

To implement Enterprise Project Governance, which demands a change in organizational mind-set, a start-up stakeholder approach is required—one that focuses on the unique issues of managing an organizational change project. Even when an enterprise philosophy already reigns, stakeholders have to be managed to keep the organization lively and productive.

EPG also serves as a bastion for solid stakeholder policies for projects that are vital to the strategic success of the organization. EPG is all about making sure the right combination of projects are done right, in particular, mega projects or other highly strategic ventures. So EPG has a role for ensuring that key project-related executives, sponsors, and professionals across the organization are up to speed on managing all the players affecting their projects.

A Stakeholder Threesome

A case in point involves the complex stakeholder issues associated with the construction of a gigantic military aircraft for the Indian Air Force (IAF). The IAF partnered with the U.S. Air Force (USAF) and subsequently signed with aeronautics contractor Lockheed Martin in March 2008 to design and build six high-tech C-130J Super Hercules planes.

The complex aircraft fabrication project included more than just building planes, thus involving stakeholders outside the manufacturing process. Support systems, spare parts supply and warehousing, maintenance equipment, and training programs were also part of the picture. Personnel were required in the primary settings of the stakeholders: New Delhi (IAF), Washington, D.C. (USAF), and Marietta, Georgia (Lockheed Martin).1

For Lockheed Martin, the three-way relationship among major stakeholders was not normal practice. “The IAF didn’t understand the process of working through the U.S. government or Lockheed Martin’s foreign military sales process,” said Lockheed’s Director and Project Manager Abhay Paranjape. “And Lockheed Martin had to realize that this was the first aircraft India has bought from the United States in decades. So we didn’t have a good understanding of IAF requirements, procedures, and processes.”

The stakeholder issues were successfully managed through a combination of long-distance virtual communications, periodic face-to-face group meetings, and effective governance practices among the three major players. This combination contributed heavily to the two-months-ahead-of-schedule delivery of the first aircraft in December 2010.

The triangular relationship created challenges in stakeholder management and raised issues on project governance. Early on, it was recognized that the collaborative relationship between the two air forces would require extensive dialogue and adjustment. Thus the parties established governance practices that ensured smooth communications throughout the project. When Lockheed Martin entered the scene, additional negotiations involving the full stakeholder threesome took place to ensure overall stakeholder alignment. For the IAF C-130 project and other major undertakings that are vital to the goals of contracting parties, the issues of stakeholder management and project governance are key success factors. Part of the mission of EPG is to make sure that those issues are systematically dealt with on all projects across the enterprise.

Power, Politics, and Influence

EPG is all about power, politics, and influence. Although structure and procedures are also relevant factors, these more amorphous issues are what ultimately determines the effectiveness of Enterprise Project Governance. The concepts are described in this chapter. If these views are not part of the culture of the organization, it is recommended that a workshop program be carried out to ensure that the primary stakeholders know how to navigate in the waters of EPG.

EPG and Power

“Power is the ultimate aphrodisiac,” Henry Kissinger said when he was U.S. Secretary of State. The statement suggests that power has an almost sensual attraction; people are drawn to power by a magnetic, quasi erotic force. Whether this is true or not, it’s a fact that power is necessary for executives and other important project players to get their jobs done. Power provides the energy to take initiative, to lay out plans, and to follow up on results. From a company standpoint, the attraction people feel to power is a healthy influence because, when power is properly used, it moves an enterprise in the right direction. For Enterprise Project Governance, here are the prevalent forms of power:

![]() Formal. Stemming from position power, formal power indicates that the player has received some charter to do a job. A scope of work is associated with that job, which is to be carried out according to the culture and values of the company. Formal power is the easiest kind to see and understand. It is usually expressed in an up-front manner.

Formal. Stemming from position power, formal power indicates that the player has received some charter to do a job. A scope of work is associated with that job, which is to be carried out according to the culture and values of the company. Formal power is the easiest kind to see and understand. It is usually expressed in an up-front manner.

![]() Relationship. “It’s not what you know, but who you know” goes the old expression. Access is a form of power, whether that access is through blood relationships, an good-old-boy network, or church or community acquaintances. Relationship power opens doors.

Relationship. “It’s not what you know, but who you know” goes the old expression. Access is a form of power, whether that access is through blood relationships, an good-old-boy network, or church or community acquaintances. Relationship power opens doors.

![]() Knowledge-Based. While authority can be formal, it can also be couched in knowledge. Nobel Prize winners, for instance, are not always steeped in formal power, but their recognized knowledge makes them leading authorities, which in turn becomes power. Thus power and authority go hand in hand.

Knowledge-Based. While authority can be formal, it can also be couched in knowledge. Nobel Prize winners, for instance, are not always steeped in formal power, but their recognized knowledge makes them leading authorities, which in turn becomes power. Thus power and authority go hand in hand.

![]() Competence. Competence power transcends that of knowledge, in that the person is recognized as someone who gets things done. Power derived from competence stems both from technical knowledge and from behavioral and political skills.

Competence. Competence power transcends that of knowledge, in that the person is recognized as someone who gets things done. Power derived from competence stems both from technical knowledge and from behavioral and political skills.

Cultivating one or a combination of these power factors considerably boosts the potential power of executives and other significant players in an enterprise. From a stakeholder management viewpoint, it makes good sense to establish a firm power base and even to brandish power when necessary, provided that ethics and people’s feelings are respected. It takes power to get things done, particularly in a wide-reaching web of power brokers exercising their influence across the enterprise. Here are tips on how executives and other players can use power effectively in the organization:

![]() Understand the organization. All organizations have a fundamental culture. They have traditions and a history. Even though major surgery may be needed, understanding the essence of an organization is fundamental to putting together the governance of a project-oriented enterprise.

Understand the organization. All organizations have a fundamental culture. They have traditions and a history. Even though major surgery may be needed, understanding the essence of an organization is fundamental to putting together the governance of a project-oriented enterprise.

![]() Polish up on interpersonal skills. For Enterprise Project Governance to work, both senior executives and project team members must have high levels of the emotional quotient of behavioral and political skills needed to deal intelligently with the power factors present.

Polish up on interpersonal skills. For Enterprise Project Governance to work, both senior executives and project team members must have high levels of the emotional quotient of behavioral and political skills needed to deal intelligently with the power factors present.

![]() Build up image. Just as products need to be marketed to convey an image, all key players in a project setting need to keep personal images polished. Call it self-marketing, blowing your own horn, or whatever, the personal image as a competent and articulate project-based player deserves constant nurturing.

Build up image. Just as products need to be marketed to convey an image, all key players in a project setting need to keep personal images polished. Call it self-marketing, blowing your own horn, or whatever, the personal image as a competent and articulate project-based player deserves constant nurturing.

![]() Develop and cultivate allies. Enterprise Project Governance is like a team sport. Individual actions become significant only within the context of a series of actions. As in volleyball, where one player receives the ball, and a second sets it up for the third player to spike, players in projectized organizations require support from teammates.

Develop and cultivate allies. Enterprise Project Governance is like a team sport. Individual actions become significant only within the context of a series of actions. As in volleyball, where one player receives the ball, and a second sets it up for the third player to spike, players in projectized organizations require support from teammates.

EPG and Politics

Politics has been described in government circles as the “art of the possible.” The possible in companies depends on the art of conciliating differing interests and opinions among the people who make up the network of power in the organization. Executives, therefore, need to act politically to influence the company’s decision-making process in order to bring about decisions consistent with their interests and opinions—and that at the same time are possible. The key to politics lies in understanding that facts are not the important factor in making political decisions. Much more important are the interests at stake, such as departmental or sectorial interests, power-based interests, economic and financial interests, and personal agendas. And most important, the opinions of individuals, formed for whatever historical, cultural, or psychological reasons, are the essence of everything political. When managing stakeholders in an enterprise setting, here are some recommended techniques for successful politicking in favor of a given cause:

![]() Plant seeds of action by casually remarking on issues, circulating articles, or citing third parties.

Plant seeds of action by casually remarking on issues, circulating articles, or citing third parties.

![]() Don’t press the issue; give people time to absorb and process new ideas and issues.

Don’t press the issue; give people time to absorb and process new ideas and issues.

![]() Involve others because politics by its nature includes and affects groups of people.

Involve others because politics by its nature includes and affects groups of people.

![]() Give details in support of your cause as discussions evolve.

Give details in support of your cause as discussions evolve.

![]() Include the suggestions of others, and negotiate any details involving the interests of all.

Include the suggestions of others, and negotiate any details involving the interests of all.

EPG and Influence

In an enterprise setting, influence is closely related to competence. The greater the level is of technical and behavioral competence, the greater the level of influence will be. Because of the large number of network and matrix relationships in an enterprise setting, power and politics have to be wielded in a subtle fashion, using different forms of influence. Here are the assumptions for effective influence management:

![]() Most executives possess the basic experience and knowledge necessary to exercise influence management, yet they do not fully utilize that potential.

Most executives possess the basic experience and knowledge necessary to exercise influence management, yet they do not fully utilize that potential.

![]() An easy way to influence others is to give positive feedback, provided the feedback is timely, relevant, and sincere.

An easy way to influence others is to give positive feedback, provided the feedback is timely, relevant, and sincere.

![]() The art of listening, although an apparently passive stance, is a powerful technique for influencing others. It creates a bond that inevitably pays dividends in terms of relationships and goodwill.

The art of listening, although an apparently passive stance, is a powerful technique for influencing others. It creates a bond that inevitably pays dividends in terms of relationships and goodwill.

![]() The classic approach of different strokes for different folks continues to be valid when it comes to influencing other people. This means customizing behavior for individuals with differing characteristics so that each person gets made-to-order treatment.

The classic approach of different strokes for different folks continues to be valid when it comes to influencing other people. This means customizing behavior for individuals with differing characteristics so that each person gets made-to-order treatment.

![]() Interface management, or the building of bridges for communication and conciliating interests between company stakeholders, is a key activity in projectized organizations.

Interface management, or the building of bridges for communication and conciliating interests between company stakeholders, is a key activity in projectized organizations.

![]() Multidirectional relationships between executives and key project players, involving vertical, horizontal, and diagonal communications, are the norm in organizations that are managed via projects.

Multidirectional relationships between executives and key project players, involving vertical, horizontal, and diagonal communications, are the norm in organizations that are managed via projects.

![]() Conflict management is part of the executive’s job in any organization; in organizations managed by projects, the propensity for conflict is even greater because of the multiple relationships.

Conflict management is part of the executive’s job in any organization; in organizations managed by projects, the propensity for conflict is even greater because of the multiple relationships.

Structured Stakeholder Management

The power, politics, and influence issues involved in managing projects across an enterprise can be looked at using a structured format. A stakeholder management plan maps out a structured way to influence each player. The key word is “structured,” as opposed to using a purely intuitive approach. Although stakeholders have always been managed in some form, structured stakeholder management allows for the comprehensive planning and staging of what needs to be done to influence the doers and opinion makers.

Dealing with stakeholders in a customized, needs-based manner boosts the chances for smooth sailing in a project environment. Conversely, the lack of a systematic slant on handling both the obvious decision makers and the behind-the-scenes opinion makers is an open invitation to disaster: Sooner or later a disgruntled stakeholder will toss a curveball. At minimum, the fix for an unexpected situation entails backtracking, rework, and the management of grief.

Walmart, Battling for the Hearts and Minds of Stakeholders

Walmart’s worldwide status as the number one company in retailing has been frequently documented on Fortune magazine’s annual lists. The company is famous for its values of hard work, customer satisfaction, and employee appreciation, expressed since the beginning by founder Sam Walton in 1962.

In spite of these admirable qualities, since 2000, Walmart has been the target of severe criticism with respect to its business practices. Accusations leading to lawsuits included low wages, gender discrimination, and the use of illegal immigrant labor.2 The University of Michigan’s American Customer Satisfaction Index has rated Walmart at the low end of its list since the index’s inception in 2004.

Consumer interest groups, as well as politicians and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), launched campaigns against the company using techniques like lobbying, media movements, and grassroots initiatives. The consumer groups aim to influence the entire consumer market by targeting the worldwide leader. Walmart Watch’s mission is to hold Walmart accountable for its impact on communities, the workforce, the retail sector, the environment, and the nation’s economy. Walmart Watch challenges the company to fully embrace its corporate responsibilities and to live up to its position as the largest corporation in the United States.3, 4

Walmart’s public relations and reputation management (PR) was nonexistent until being the focus of so many critics. In 2005, Walmart created a so-called war room with some of the biggest names in the PR industry to preempt negative attacks from manufacturer to storefront. Walmart’s most visible and concerted effort to give back to society has been its sustainability program, encompassing many of their initiatives in external communication and adopting the concept that sustainability goes beyond the environment and has broader economic and social components, including health care, economic opportunity, and the quality of life of the people who make the products they sell.

At the end of 2007, Walmart released the first Sustainability Progress to Date, 2007–2008, tracing their commitment to sustainability, from consumer to employee, from manufacturer to storefront. The report points out:

We have found that there is no conflict between our business model of everyday low costs and everyday low prices and being a more sustainable business. To make sustainability sustainable at Walmart, we’ve made it live inside our business. Many of our environmental sustainability efforts, for example, mean cost savings for us, our suppliers and our customers.5

To make sustainability live inside their business—an aim that requires flawless execution—they created Sustainable Value Networks to integrate practices across the business, bringing together leaders from the company, suppliers, academia, government, and NGOs to explore challenges and to develop solutions to benefit business, as well as local and global communities. Each network has a sponsor at the level of senior vice president and is led by a network captain who has a sustainability team overseeing the activities. Walmart took the following steps to deal with a critical situation with many stakeholders involved:6, 7

![]() Created the war room to deal with the problem.

Created the war room to deal with the problem.

![]() Identified and analyzed all the stakeholders having an interest in the problem and desired outcome (both positive and negative).

Identified and analyzed all the stakeholders having an interest in the problem and desired outcome (both positive and negative).

![]() Planned how to engage the stakeholders by creating a sustainability program to promote change with many of the issues involved in their external communication.

Planned how to engage the stakeholders by creating a sustainability program to promote change with many of the issues involved in their external communication.

![]() Developed a communication and reporting plan.

Developed a communication and reporting plan.

![]() Started executing the program, adjusting and improving it over the years and issuing a consolidated report every year.

Started executing the program, adjusting and improving it over the years and issuing a consolidated report every year.

The program approach using the sustainability flag was used by Walmart to ward off attacks by opposing groups. The fact that the company was under siege brings out a colloquial truism about the management of stakeholders: If stakeholders are not managed proactively, they will throw rocks at you. While the defensive program proved reasonably effective in dealing with Walmart’s PR issues concerning the opposition stakeholders, proactive, preventive stakeholder management is a more effective way to go.

Who Are the Stakeholders Anyhow?

The first manned moon shot in 1969 had lots of stakeholders, including the president of the United States, the congressional leaders, the Soviets, the media, and, of course, NASA.

Certainly first-on-the-moon Neil Armstrong felt himself a major stakeholder in the Apollo project. Some people carry higher stakes than others, just as the proverbial pig’s stake in a dish of ham and eggs is unquestionably greater than that of the chicken. Folklore has it that the original Apollo project objective was, “Before the end of this decade, we will land a man on the moon.” It goes on to say that NASA astronauts added the words “and bring him safely back to Earth.”

Here are some stakeholders who carry different stakes in projects:

![]() Project Champions. The champions are responsible for the project’s existence. They initiate the movement and are ultimately interested in seeing the project get to its operational stage. They shape the way an organization perceives and manages its projects. These champions determine to what extent the company is prepared to manage multiple projects. Examples of those who champion the cause are investors, project sponsors, upper management overseers, clients (external or internal), and politicians (local, state, federal).

Project Champions. The champions are responsible for the project’s existence. They initiate the movement and are ultimately interested in seeing the project get to its operational stage. They shape the way an organization perceives and manages its projects. These champions determine to what extent the company is prepared to manage multiple projects. Examples of those who champion the cause are investors, project sponsors, upper management overseers, clients (external or internal), and politicians (local, state, federal).

![]() Project Participants. This group performs the project work. From an Enterprise Project Management standpoint, these stakeholders merit special care because they are the ones who bring home the bacon. The role of the project team members is related to the project itself; they are usually not involved in the conceptual phases and likely will not follow into the operational phases. Some of these key players are project managers, team members, suppliers, contractors, specialists, regulatory agencies, and consultants.

Project Participants. This group performs the project work. From an Enterprise Project Management standpoint, these stakeholders merit special care because they are the ones who bring home the bacon. The role of the project team members is related to the project itself; they are usually not involved in the conceptual phases and likely will not follow into the operational phases. Some of these key players are project managers, team members, suppliers, contractors, specialists, regulatory agencies, and consultants.

![]() External Stakeholders. These parties, while theoretically uninvolved, may suffer from project fallout. In other words, they are affected by the project as it unfolds, or by the final results of the project once it is implemented. They also may influence the course of a project. Some of these external influences may not be manageable by the team assigned to a project; in such cases, support is required from elsewhere in the organization. Examples of external stakeholders are environmentalists, community leaders, social groups, the media (press, TV, etc.), project team family members, and opposition groups, as described in the Walmart case.

External Stakeholders. These parties, while theoretically uninvolved, may suffer from project fallout. In other words, they are affected by the project as it unfolds, or by the final results of the project once it is implemented. They also may influence the course of a project. Some of these external influences may not be manageable by the team assigned to a project; in such cases, support is required from elsewhere in the organization. Examples of external stakeholders are environmentalists, community leaders, social groups, the media (press, TV, etc.), project team family members, and opposition groups, as described in the Walmart case.

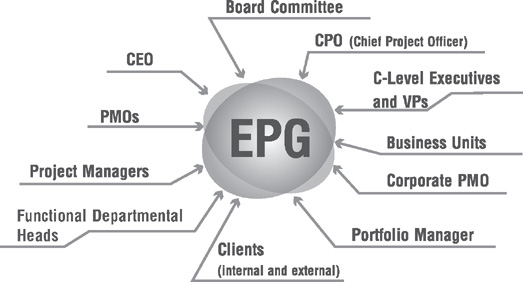

Exhibit 8-1 depicts some of the major stakeholders in the EPG arena.

How Does the Stakeholder Model Apply to Enterprise Project Governance?

For Enterprise Project Governance, principal stakeholders fall into the champion category. These champions have the power to initiate projects and shape their ultimate impact on the organization, and their decisions end up affecting all other internal and external stakeholders. In generic terms, the champions include investors, project sponsors, upper management overseers, clients (external or internal), and politicians (local, state, federal). A spotlight on EPG itself, however, reveals a more detailed list of parties with stakes in the structuring and managing of projects across the organization. Here are some of them:

Exhibit 8-1. Stakeholders in EPG Environment

![]() Board Members. If the board has a strategic committee or something similar, then the committee chair exerts influence on EPG.

Board Members. If the board has a strategic committee or something similar, then the committee chair exerts influence on EPG.

![]() CEO, Executive Committee members, Chief Project Officer, or VP of Special Projects. The CEO is ultimately responsible for EPG but is likely to delegate that responsibility to another C-level executive.

CEO, Executive Committee members, Chief Project Officer, or VP of Special Projects. The CEO is ultimately responsible for EPG but is likely to delegate that responsibility to another C-level executive.

![]() Strategic PMO, Corporate PMO, or Project Portfolio Manager. In some cases, the responsibility may be delegated directly to high-level PMOs or portfolio managers.

Strategic PMO, Corporate PMO, or Project Portfolio Manager. In some cases, the responsibility may be delegated directly to high-level PMOs or portfolio managers.

![]() Business Unit or Departmental PMOs. Operational-level PMOs carry out a major role in ensuring that project management policies are implemented and followed.

Business Unit or Departmental PMOs. Operational-level PMOs carry out a major role in ensuring that project management policies are implemented and followed.

![]() Project Managers. These are the hands-on players that transform the overall EPG policies into reality on each project.

Project Managers. These are the hands-on players that transform the overall EPG policies into reality on each project.

What Are the Steps in Stakeholder Management?

The approach for managing stakeholders, outlined in this section, is fully applicable in the EPG arena.

While intuition is important when dealing with stakeholders, a step-by-step overview is recommended to ensure that all issues are taken into consideration.

![]() Identify and gather preliminary information about stakeholders. Make a list of all who lay claim, in any form, to a share of the project’s outcome. In the case of the project to implement Enterprise Project Governance, who are the champions, the project participants, and the external stakeholders? Remember that stakeholders must be identified as individuals—with names and faces—as opposed to departments or groups. Be sure to include the following information:

Identify and gather preliminary information about stakeholders. Make a list of all who lay claim, in any form, to a share of the project’s outcome. In the case of the project to implement Enterprise Project Governance, who are the champions, the project participants, and the external stakeholders? Remember that stakeholders must be identified as individuals—with names and faces—as opposed to departments or groups. Be sure to include the following information:

![]() Name

Name

![]() Background

Background

![]() Role of the individual

Role of the individual

![]() Special circumstances

Special circumstances

![]() Past experiences

Past experiences

![]() Analyze each stakeholder’s probable behavior and potential impact. To what extent can stakeholders have an impact on a project? And to what extent can their behavior be influenced? Here is a simple way for classifying the stakeholders:

Analyze each stakeholder’s probable behavior and potential impact. To what extent can stakeholders have an impact on a project? And to what extent can their behavior be influenced? Here is a simple way for classifying the stakeholders:

![]() A = Stakeholders who can be influenced strongly

A = Stakeholders who can be influenced strongly

![]() B = Stakeholders who can be influenced moderately

B = Stakeholders who can be influenced moderately

![]() C = Stakeholders who can be influenced very little

C = Stakeholders who can be influenced very little

Stakeholders can also be classified by their degree of impact on the project. For instance:

![]() D = Stakeholders who have a strong impact on the project

D = Stakeholders who have a strong impact on the project

![]() E = Stakeholders who have a medium impact on the project

E = Stakeholders who have a medium impact on the project

![]() F = Stakeholders who have a weak impact on the project

F = Stakeholders who have a weak impact on the project

![]() Develop stakeholder strategies. Stakeholders are the way they are—except when they are different! Just as in team sports, it takes people with unique characteristics, each carrying out a differing role, to manage a project-oriented organization. Professional teams, whether football, basketball, soccer, or cricket, all have on-field and off-field players. The off-field players include owners, managers, promoters, coaches, athletes, and support groups. Organizations that manage by project have a similar cast, and all parties have to do their parts for the organization’s goals to be met. A plan needs to be developed to spell out how each stakeholder should be managed.

Develop stakeholder strategies. Stakeholders are the way they are—except when they are different! Just as in team sports, it takes people with unique characteristics, each carrying out a differing role, to manage a project-oriented organization. Professional teams, whether football, basketball, soccer, or cricket, all have on-field and off-field players. The off-field players include owners, managers, promoters, coaches, athletes, and support groups. Organizations that manage by project have a similar cast, and all parties have to do their parts for the organization’s goals to be met. A plan needs to be developed to spell out how each stakeholder should be managed.

To understand how to handle stakeholders, these questions require responses:

![]() What are the stakeholders’ stated objectives or position?

What are the stakeholders’ stated objectives or position?

![]() What is the likely hidden agenda?

What is the likely hidden agenda?

![]() What influences are exerted on the stakeholder?

What influences are exerted on the stakeholder?

![]() Who is the best person to approach this stakeholder?

Who is the best person to approach this stakeholder?

![]() What tactics are best suited?

What tactics are best suited?

![]() What is the best timing?

What is the best timing?

![]() Implement and maintain the strategies. This phase calls for carrying out activities planned in the previous stage, via a stakeholder management implementation plan. This plan pinpoints actions, responsible parties, and completion dates for the actions. Then that plan is adjusted and reworked as needed. But, to begin, the stakeholder strategies are implemented in accordance with the relative importance of the stakeholders. For instance, there would be major emphasis on a small number of stakeholders who have a strong impact, normal efforts for an intermediate group, and moderate attention to stakeholders reckoned to have a lesser impact.

Implement and maintain the strategies. This phase calls for carrying out activities planned in the previous stage, via a stakeholder management implementation plan. This plan pinpoints actions, responsible parties, and completion dates for the actions. Then that plan is adjusted and reworked as needed. But, to begin, the stakeholder strategies are implemented in accordance with the relative importance of the stakeholders. For instance, there would be major emphasis on a small number of stakeholders who have a strong impact, normal efforts for an intermediate group, and moderate attention to stakeholders reckoned to have a lesser impact.

Influencing Stakeholders to Buy In: Not an Easy Task

A bank owned by a European automaker faced a stakeholder alignment challenge when several project management thrusts were taking place within the enterprise at the same time. The bank’s Achilles’ heel was a centralized credit approval project that was intended to speed up processing and eliminate bureaucracy at car dealerships, where credit applications were traditionally dealt with. The project was a source of major conflict between the information technology people, who were managing the effort, and upper management, who exerted heavy-handed pressure to get it back on track. The head of training perceived a need for improved project performance and arranged for courses on the basics of project management. These courses did not take place, however, because the bank’s quality group became convinced that the time was right to introduce a management-by-projects slant for running the organization, but they needed a go-ahead from upstairs to proceed. Upper management did not give the nod because the executives were not attuned to the need for a strategic approach to handling projects. The IT people, who were competent technically, had little or no training in how to run projects. No one, at any level, had taken into account the fact that the new structure would substantially shrink the functions of dozens of people and would play topsy-turvy with the power balance within the bank. This situation is a classic portrait of unaligned stakeholders. Each had a different perception of what the problems were and what needed to be done.

The responsibility for stakeholder management lies with the party who has the greatest awareness of the need for Enterprise Project Management. In the example of the bank, the quality group carried the burden of influencing stakeholders to rally around the management-by-projects philosophy. Once that commitment was received—and after an in-house awareness talk by a guest expert—the quality group began making headway toward changing the organization to a manage-by-projects format. This example illustrates the two principles given earlier: First, analyze who the stakeholders are and their stakes and, second, introduce your new approach to management in a way that is sensitive to the interests and concerns of all involved.

Promoting Project Management Among Company Stakeholders

Creating awareness is the first hurdle in implementing EPG in an organization. The change agents involved could be upper management, middle management, or organizational change agents or internal facilitators. No matter, the procedure for getting people to sign on is much the same. Since participation is needed for anything to work, several articulated moves, such as training programs, talks, and campaigns, can spread the spirit of project management throughout the company.

Another view is the evolution theory to promote a cause. Author Tom Peters looks at the issue like this: “How do you ‘sell’ this concept ‘up’ to your bosses? Don’t!” Instead, he says, the positive results obtained through project management should filter up through the system and do their own marketing.8 Third-party marketing, then, by way of the customer or internal client, is a way to let bosses know what a great job is being done via the diligent application of project management.

If Peters’s approach sounds a bit simplistic, there are more proactive ways to promote project management among corporate stakeholders. One way is to compare performance with other companies or participate in benchmarking groups to see what practices are prevalent and effective. Numbers are another way to go; showing the potential savings of project management will surely move even the most resistant stakeholder.

Sponsors: Key Stakeholders in EPG

The figure of the sponsor provides the connection between the formal organization and the projects designed to carry company strategies. It’s a crucial role that requires qualified people. As renowned international consultant Terence Cook-Davies points out, “This role is normally taken on by senior executives since only experienced top managers are likely to have credibility and knowledge of the permanent organization to interact effectively with other senior executives on the impact of projects with strategic and operational issues.”9 One of the roles of Enterprise Project Governance is to ensure that the organization has enough competent and well-trained sponsors to ensure that company projects stay on course.

This level of competence is particularly relevant in formal settings where the figure of the sponsor is institutionalized and specific responsibilities are associated with the role. From a practical standpoint, however, the sponsor role is not always formalized or fully understood by the sponsor or by those with whom the sponsor interacts. This creates an area of fuzziness in terms of organizational responsibility. The formal institutionalized responsibilities of the sponsor are outlined next, along with comments for sponsors operating in less formalized settings.

Here are the roles that describe the essence of sponsors’ contributions to EPG:

![]() Be responsible for the business case from start to finish (from proposal to benefits reaped).

Be responsible for the business case from start to finish (from proposal to benefits reaped).

![]() Act as a godfather figure to the project manager.

Act as a godfather figure to the project manager.

![]() Provide political support, and champion the cause.

Provide political support, and champion the cause.

![]() Govern the project.

Govern the project.

These roles, properly carried out, are a near guarantee for success, whereas poor sponsorship tends to lay the groundwork for project failure.

The Business Case from Start to Finish

A vital role of the sponsor is to see that the project in question adheres to achieving the business objective. This requires a business case that provides the justification for committing resources to the project, based on the assumptions and objectives outlined in the project charter. The sponsor’s role is then to ensure that the proposed facility, product, service, or improvement is duly delivered within the requirements and ultimately spawns the benefits desired as expressed in the business case.

The project sponsor is generally involved up front in the approval process of the business case, which outlines the desires of the organization’s strategists. Sundry factors, however, influence the evolution of the project. So the sponsor is in fact a project guardian, charged with making sure the project does not sway off course and articulating adjustments as needed toward a happy project ending.10

The Sponsor as Godfather to the Project Manager

The sponsor’s role as stakeholder manager with other senior executives is essential for the project manager to carry out his or her job. The sponsor provides a political shield to keep the project manager from being distracted from management duties. This role is necessary to meet challenges that can be resolved only at executive-suite levels. The sponsor takes on political roadblocks, such as reluctance by functional departments to provide resources or a lack of support by key players.

The godfather role involves providing political coverage as well as giving advice, counsel, and guidance to the project manager. Ultimately, the sponsor’s success is tied directly to the success of the project manager, who deals with the daily issues and is charged with implementing the project. The sponsor may have to give some coaching and suggest directions on specific issues.

Even as the project is executed, the enterprise sponsoring it will be undergoing changes of its own. In this context, the sponsor is the one person best able to relate the overall enterprise risk, with its associated sustainability challenges, to the business case and to the uncertainty of the project itself.

Carrying Out Leadership Roles

How stakeholders in the organization see a project depends on the leadership of the sponsor. The challenges to the sponsor’s leadership come from three different directions: project-related, interpersonal relationships, and sponsor self-management. All of these challenges are part of the sponsor’s overarching responsibility as change agent because the desired business benefits are reaped only when the proposed change happens through implementing the project.

The project-related and relationship leadership issues are relatively intuitive for most sponsors. Yet the overall responsibility for sponsorship requires some reflection on sponsor self-management. This calls for internal assessment by the sponsor regarding the necessary allotment of time and effort required to do the job right.

The Sponsor as Governor of the Project

The sponsor, who invariably has other major responsibilities in the organization, is in fact responsible for governing the project. Of course, the project manager runs the project itself and is charged with the details of planning, implementation, and control. Yet overall governance of the project befalls the sponsor, who may or may not have deep knowledge of projects. Therefore, it’s essential to establish and monitor major checkpoints and gain responses to specific questions in each phase, such as:

![]() Preproject. Is the business plan coherent with the organization’s strategy?

Preproject. Is the business plan coherent with the organization’s strategy?

![]() Concept. Does the project charter provide full definitions of objectives, benefits, resources, and time-cost parameters?

Concept. Does the project charter provide full definitions of objectives, benefits, resources, and time-cost parameters?

![]() Planning. Does the project plan include sufficient detail to carry out the project effectively, including topics such as quality, risk, documentation, scope packages, and communications management?

Planning. Does the project plan include sufficient detail to carry out the project effectively, including topics such as quality, risk, documentation, scope packages, and communications management?

![]() Implementation. Is the formal reporting timely, and are regular meetings carried out to ensure effective implementation?

Implementation. Is the formal reporting timely, and are regular meetings carried out to ensure effective implementation?

![]() Closeout. Are subcontracts being closed out appropriately, and is there a transition plan for the operational phase?

Closeout. Are subcontracts being closed out appropriately, and is there a transition plan for the operational phase?

![]() Postproject. Are lessons learned fully documented? What postproject actions need to be made to optimize the benefits desired?

Postproject. Are lessons learned fully documented? What postproject actions need to be made to optimize the benefits desired?

In some cases, the sponsor may be supported by a formal governance body, such as a project control board, steering group, or development committee.

Conclusions

Successful stakeholder management calls for a structured approach to deal with the parties who have vested interests in the project, and it is essential for effective Enterprise Project Governance. This means that all players (champions, participants, and external stakeholders) require proactive management; therefore, stakeholder management comes into play in two distinct ways. First, to implement the Enterprise Project Governance project, the stakeholders have to be managed during the implementation phase. Second, once the concept is put into place, company executives must ensure that the stakeholder concept becomes a part of the company culture. The sponsor’s role is critical to the success or failure of projects and to the effectiveness of Enterprise Project Governance. The role is multifaceted, ranging from caring for the business case from start to finish, acting as a godfather figure to the project manager, carrying out leadership roles, and governing the project.