CHAPTER 18

Risk Appetite and Tolerance in Competitive Strategy

JAMES DARROCHAND

CIT Chair in Financial Services, Schulich School of Business, York University

DAVID FINNIE

Founder and President, Marshall, Griffith & Woods Ltd.

INTRODUCTION

Frank Knight,1 the well-known Chicago School economist, first noted that uncertainty is the source of corporate profits. It is uncertainty that provides opportunity for organizations to pursue strategies and tactical plans to create and capture profits. It follows, therefore, that organizations need to effectively manage themselves within their environment to leave only uncertainty that results in opportunity and profits or that is impractical to remove or expected to be immaterial to results. The goal of risk management is to lessen the downside possibilities and enhance the opportunity for gain. This chapter fully endorses that view and considers effective risk management as a source of sustainable competitive advantage—the holy grail of strategic planning.

Risk management creates a more robust competitive strategy through a thorough understanding of the risks in the business, and, through the intelligent management of those risks, to ensure the corporation only takes risks that:

- Support its purpose and strategy.

- It understands.

- It has the capability of managing.

- It has the resilience to recover from risks that materialize.

The articulation of the corporation's ability and willingness to take risk is captured in its risk appetite and risk tolerance documentation. We discuss definitions to ensure that we are clear on what is meant by risk appetite and risk tolerance and we put these terms in the context of the remainder of the chapter.

We outline key considerations in what determines an organization's ability to take risk. These considerations are often labeled risk capacity and/or capability. We use both terms with the former, risk capacity, used to capture organizational structural elements such as financial or operational leverage, and the latter, risk capability, used to capture organizational functionality such as the ability to appropriately identify, assess/measure, monitor, report, manage, and plan for risk-taking outcomes.

We spend a short time on the importance of linking risks to the corporation's purpose and strategy, the effect the business model can have on risk taking, and the need to be very clear on the risk authorities granted by the board of directors. These elements create the governance structure within which risk taking is undertaken.

Following the material on strategy and risk capacity and capability we consider the willingness to take risk. The purpose and strategy of the organization means that only value-adding risks should be retained. A key consideration is the differentiation between risks taken to earn return and those that are necessary to operate and cost-prohibitive to eliminate entirely.2

We summarize the material in the context of the key theme of this material—which risks to keep and which to transfer, reduce, or otherwise mitigate to drive profitable performance and realize on the organization's strategy.

We conclude the chapter with a description of the key elements in the articulation of the risk appetite and tolerance. This includes the necessary links to strategy and authorities as well as the statement of risk limits and related requirements.

CONSIDERING RISK APPETITE AND TOLERANCE

ISO, the international organization for the standardization of industrial standards, recognizes risk appetite and tolerance in ISO Guide 73, Risk management—Vocabulary.

There are many sources of definitions for risk appetite and risk tolerance but they all have the same themes that are captured by ISO so we introduce risk appetite and risk tolerance through the ISO definitions:3

- Risk appetite: the amount and type of risk an organization is willing to accept in pursuit of its business objectives.

- Risk tolerance: the specific maximum risk that an organization is willing to take regarding each relevant risk.

As can be readily seen, these definitions lack clarity in several ways.

First, why is risk appetite defined relative to “the amount and type of risk an organization is willing to accept,” apparently in aggregate, while risk tolerance is defined relative to “each relevant risk”? Further, why would an organization go beyond the risk it is willing to accept as expressed in its risk appetite range and tolerate an additional amount of risk to reach the maximum it would take?

The answer to the second question is embedded in the answer to the first. However, rather than explain the definitions, we suggest new definitions that provide additional clarity and explicitly recognize the importance of strategy, risk capability, and risk capacity:

- Risk appetite: the types of acceptable risks consistent with the organization's strategy and capabilities, the aggregate amount of risk acceptable to the organization, consistent with the organization's capacity, and the range of acceptable risk exposures for each type of risk consistent with the organization's strategy, capabilities, and capacity.

The risk appetite definition, with its use of “range of acceptable risk exposures,” appears to have eliminated the need for the term risk tolerance. This is largely true, but the term can be maintained to more explicitly express the upper limit of the range for individual risks included in the risk appetite definition—in effect, the ISO definition with the addition of an aggregate tolerance.

- Risk tolerance: the specific maximum risk that an organization is willing to take regarding each relevant risk and the amount of risk an organization is willing to take risk- and enterprise-wide consistent with the organization's strategy, capabilities, and capacity.

For additional clarity, we have added references to organizational strategy, risk capacity, and risk capability in these definitions. These are essential elements in risk appetite and tolerance statements. The organization's purpose and supporting strategy determine the inherent risks in the organization and the risk capacity and capability determine the ability to effectively manage these risks through appropriate identification, assessment/measurement, monitoring and reporting, and resiliency planning.

In summary, when considering risk appetite and tolerance, we are considering the risks that an organization chooses to take in order to effectively pursue its strategic objectives. It identifies those risks and sets the range of acceptable exposures both in aggregate and across each risk type.

ABILITY TO TAKE RISK

An organization's ability to take risk is governed by seven factors. The importance of each factor may vary by industry and individual organization. However, the first two factors are universally applicable, and are common sense. They are:

- An organization must only take risks in support of its board-approved corporate strategy.

This should be self-evident. Unfortunately, organizations sometimes do take risks without considering the strategic fit or implications and may, as a result, take risks not acceptable within the board approval.

Later we build out how strategy and risk need to be integrated to create a competitive position. For now, we simply note that every strategy introduces, amplifies, diversifies, or otherwise affects the risks taken by the organization.

A couple of examples can illustrate this in simple terms.

An organization that is focused on cost efficiencies may be able to weather price volatility more easily than a higher-cost producer. On the other hand, a low-cost organization may not be able to build the capital reserves to allow for additional risk taking.

An organization with a high-growth or innovative strategy faces risks associated with new product or new market development, depending on the source(s) of the desired growth. Examples would include Walmart as a high-growth organization and Apple as a highly innovative organization. As Walmart's market becomes saturated, it needs a new business model to sustain growth with new segments and this transforms its risks and introduces new risks. At some point Apple's ability to create new market demand may hit the wall and it will turn to focusing on cost reductions to grow profits, and this change will also affect the risks faced.

The key is that establishing the organizational strategy and objectives determines many of the risks being taken and the ability to take risk. The strategy and risk conversations are intrinsically linked and must be considered together in an integrated manner.

- An organization should only take risks it understands.

Implied in risk understanding is risk identification. The organization must identify the risks relevant to the business. This will be developed further in the Strategy section later in this chapter.

Risks span across the organization and this understanding must extend beyond the engineer, business leader, trader, or any other individual responsible for taking and managing the risk. The understanding needs to be in place in every part of the organization involved in the taking, managing, processing, monitoring, reporting, and resiliency planning. Given that a key role of the board of directors is the creation and protection of value,4 the directors must understand the risks being taken and the manner in which they will be managed and overseen.

The organization, or collective of individuals within the organization, may be able to understand many risks beyond those appropriate for the purpose and strategy of the organization and it is necessary to always test risk taking against the corporate strategy. An example with which one of us is familiar is an attempted move from trading in commodity derivatives to support client needs, to physical delivery on expiry of the forwards offered. As a financial institution, the holding and managing of physical commodities did not fit within the client strategy (or corporate capability) and was declined by the risk function supported by the board's committee with risk oversight responsibilities.

There are two additional factors that limit the types of risk the organization can take:

- An organization should only take risks it can assess and/or measure, manage, monitor, report, and for which it can develop effective resiliency plans.

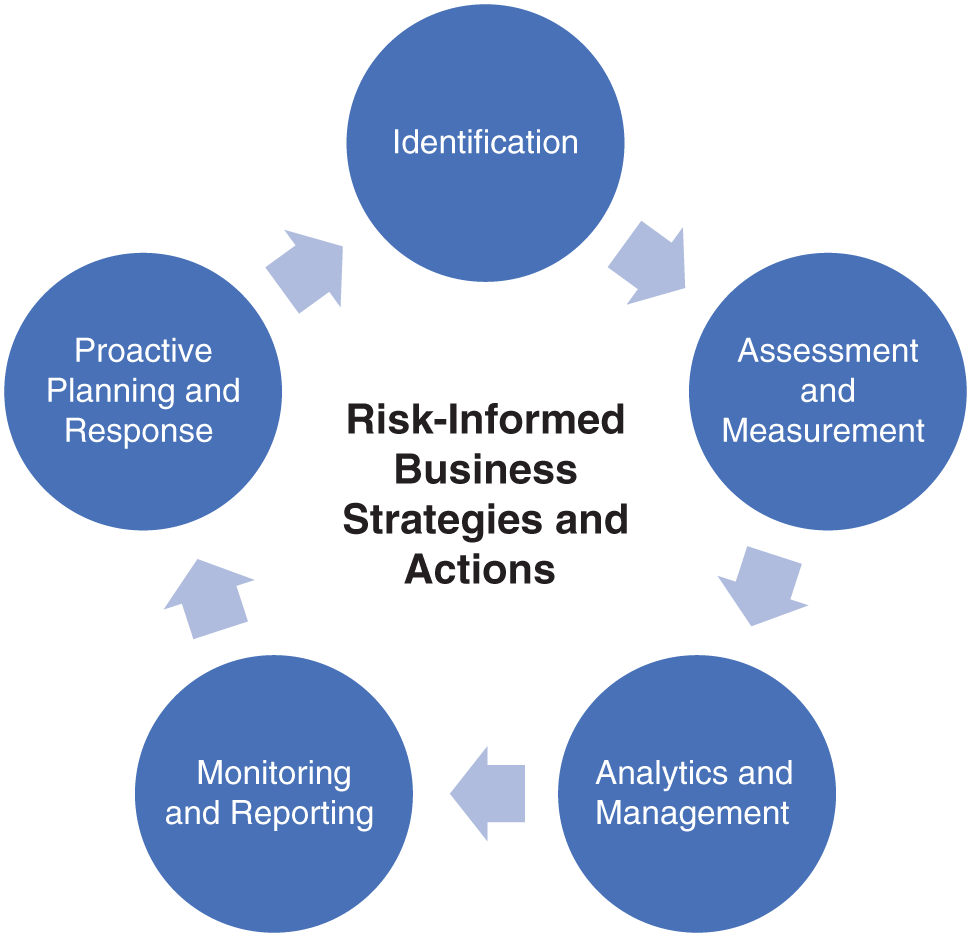

In combination with risk identification, these elements form a series of steps and actions often labeled the risk process. The objective of the risk process is to ensure that business strategies and actions are risk-informed and risk-appropriate. While this sounds simple, the span of business decisions affected is very broad. Exhibit 18.1 provides a graphic of the process.

Exhibit 18.1 The Risk Process

Risk identification involves the detection and description of risks that could compromise the ability of the organization to achieve its business objectives. The identification process begins with a clear statement of the business purpose. The purpose should provide information on the inherent risks in the business. For example, at a minimum, a lending business includes the risk of borrower defaults (credit risk), the asset/liability risk involved in funding the lending assets (market and liquidity risk), and the operational risks, including handling the ongoing interest and principal payments for both assets and liabilities, monitoring adherence to any covenants, and perfecting any security.

Each process within Exhibit 18.1 interacts with other strategic and risk management factors (e.g., risk identification with the strategic objectives, the assessment with risk criteria, analytics and management with use of resources, monitoring and reporting with the chain of command up and down the organization, the response with resources, contingency planning and review of the strategic objectives), and all loop back to the strategic process to, in combination, create competitive positioning and drive performance. In their forthcoming book on strategy, risk, and governance, Darroch and Finnie develop and explain these linkages and how integration across these factors is essential.

Risk assessment and measurement is about building an understanding of the magnitude, sources and direction, and key drivers of the risk exposures. There are risks that can be measured, and those that can only be assessed. Assessment is largely a qualitative exercise relying on experience and analytical and intuitive thinking. There may be the possibility of using some existing risk measurement approaches, although the lack of data and clear insight into the performance and risk drivers imply that this must be done with caution. Measurement approaches provide the ability to convert the barrage of data into insightful and actionable information. This provides the ability to better understand the forces driving the risks faced and opportunities available. If used properly, measurement approaches allow complex performance and risk information to be communicated in a common language, a business language.

Effective risk analytics and management is a journey of discovery. Risks transform and migrate; they emerge and dissipate. Business needs change and risk exposures and management actions change with them. Markets also change and experience different conditions that may not be adequately reflected in risk measures based on past conditions. It is necessary to undertake ongoing analysis to fully understand the possible factors driving business performance through time. The objective of this process step is to develop risk insights and a deeper understanding of possible performance outcomes to inform business management. Business management, including risk management, results in the inherent risks being managed, to the extent practical or affordable, and only residual risks being retained.

Monitoring and reporting are linked from the perspective of needing to report past and current risk positions. Reporting also requires a forward-looking view so it is also related to risk analytics. Combined, the objective is to capture risk exposures and clearly communicate with key stakeholders, including risk takers, business leaders, regulators, and the board. Under risk identification, it was noted that all risks should be identified. In risk monitoring and reporting, there is the need to include only material risks and risks that are changing (they may become material).

The key to creating effective business plans, including contingency plans, to address risks is a clear understanding of exposures and the underlying risk drivers and the critical business vulnerabilities. The identification, assessment, and analytics process steps provide this capability. The monitoring process step allows for the identification of risk-driver changes and an assessment of the level of risk in the environment. A crisis may not be able to be predicted but increasing risk can be. The plans must consider the volatility of underlying risk drivers. How quickly the environment can change affects the materiality of the risks and the nature of the required plans.

The risk process never ends. As the business environment changes and new strategic opportunities are developed, the risks must be reviewed and new risks identified, and the process continues.

The process of identifying risks and determining risk-taking capability may result in the identification of the need to build greater capability within the organization. In these cases, the capabilities to understand and complete the risk process captured in point 2 above must be developed prior to the taking of the risks.

- An organization should only take risks from which it creates and claims value.

This factor ties risk taking directly to the organization's strategy. The strategy is the pursuit of value and only those risks for which the organization earns profits or are operationally necessary to the strategy or cost prohibitive to reduce, transform, or transfer should be taken.

The first element, only take risks for which one can get paid, ties into the Investment 101 teaching in college—the risk/return trade-off, and modern portfolio theory first advanced by Harry Markowitz.5 In making investments, lending, and many other business decisions, the risk taker seeks the maximum expected return for the minimum amount of risk. An efficient portfolio, in modern portfolio theory, is a portfolio that provides the greatest amount of return for a given level of risk.

An example of a corporate business decision implicitly or explicitly employing this thinking is the willingness to accept some level of bad debts in the accounts receivable. Trying to eliminate bad debts results in sales constraints while ignoring their possibility may result in greater sales, but much lower realization of revenue.

Since the 1990s, this concept underlies the construction of most financial institution lending portfolios. Financial institutions calculate the expected loss6 of their lending portfolios and price their loans to cover those calculated losses and other operating expenses and provide a return appropriate to the level of risk. This latter concept is called risk-adjusted return on capital (RAROC) or return on risk-adjusted capital (RORAC). Oldrich Vasicek pioneered the use of structural models for credit valuation and advanced these risk-adjusted return models.7

The second element, only take risks that are operationally necessary to the strategy or cost prohibitive to reduce, transform, or transfer, reflects the fact that not all risks are directly revenue generating. Organizations take operational risks associated with transaction processing, plant operations, vendor relationships, staffing, and, increasingly, cybersecurity, among many others. These risks are necessary, although some can be reduced, transformed, or transferred.

Risk reduction approaches often result in business constraints. For example, an organization can reduce exposure to foreign exchange rates by limiting nondomestic business (including purchases of supplies), requiring payment in their domestic currency, or matching revenue and expenses by currency. Limiting foreign business can result in lost market opportunities or increased cost or limited supply of required materials. Requiring payment in the organization's domestic currency may limit market opportunities and matching may constrain growth or profitability.

Risk transformations can be taken through hedging activities. By hedging, the underlying risk is transformed into operational risk associated with the transaction processing and counterparty operations. The counterparty operations and financial condition result in counterparty risk. Risks should only be transformed if the organization has a greater understanding and capability to manage, monitor, report, and develop effective resiliency plans for the resulting risks than for the original risks and if the exchange of risks is done at a cost-effective price.

Risk transfer is an activity to shift the risks from one party to another, often considered an underlying tenet of the insurance business. Insuring risks, however, is still a form of risk transformation. The insurance company may take the risk of an event, but the organization has transaction risk, legal or contract risk, and counterparty risk. Often insuring against loss is appropriate given the expertise in certain risks and the diversification across many risks and counterparties that insurance companies have and manage. As earlier, risks should only be insured if it can be done at a cost-effective price. The insurance premium monetizes a portion of the risk in the organization's financial statements and that portion is certain and no longer dependent on a negative outcome.

The previous four factors place limitations on the types of risk an organization can take, but not the amount. In our definitions, this is the risk capability of the organization.

The following factors address the amount of risk an organization can take, or the risk capacity.

- As an organization's financial leverage increases its capacity to take other risks declines (all other things staying the same).

Up to a point, funding the capital structure through debt makes sense given tax advantages. However, at higher levels of debt, the organizational risk of bankruptcy increases, and shareholder and debtholders demand higher returns, thereby increasing the cost of capital.8 This higher level of risk and higher cost of capital result in lower resiliency to negative outcomes and constrains an organization's ability to take other risks to pursue its strategy.

This financial leverage relationship with risk is well understood in financial institutions and by financial institution regulators. Capital, particularly high-quality, liquid capital, provides the reserves to weather unforeseen circumstances. Losses arising in this way are termed unexpected losses9 by financial institutions. This concept has resulted in the concepts of risk-adjusted returns, noted earlier, and economic capital.

Economic capital in many organizations is defined as the capital required to provide a buffer for unexpected losses. The size of this buffer is set on a number of factors, which may include regulatory requirements as for financial institutions. The overall buffer size often reflects the organization's credit rating. An organization seeking a higher rating will hold more capital than a similar organization seeking a lower rating.

For clarity, we would like to define risk capital as the capital required to cover unexpected losses from all risk-taking activities of the organization. The amount can be calculated using a risk capital model that covers credit, market, and operational risks. Regulatory and rating agency models employ risk-based approaches to assess an organization's capital needs. We would like to define economic capital as the capital required to support the economics of the business, including the necessary infrastructure (critical assets for operations) and risks. This broader definition reflects the organizational need to fund and maintain critical assets necessary to its operation. The capital funding of these assets is not available to offset any losses the organization experiences.

The availability of capital to support the organization during difficult times or unexpected losses leads to the concept of the quality and fungibility of capital. Financial institution regulators have long understood the quality of capital as established through capital structures. For example, Tier 1 capital in financial regulations,10 the highest quality of capital, is the common stock, retained earnings, and some forms of preferred shares of the financial institution. This is the capital that absorbs the first losses experienced.

Going back to our definition of economic capital, not all of the Tier 1 capital, or its equivalent in commercial firms, is fungible or available for loss without compromising the sustainability of the organization. Capital needed for assets critical to the business, perhaps plant and equipment, cannot be compromised beyond a certain point. Plant and equipment can only be leveraged to a certain extent and that creates a limitation on the capital available from that source. Liquidity of capital is also an important consideration and the available capital from different assets must be viewed in the context of time necessary to realize funds. The time to realize should, of course, consider different market conditions which may be driving the need for capital.

- As an organization's operating leverage increases its capacity to take other risks declines (all other things staying the same).

Operating leverage is an organization's fixed costs as a percentage of total costs. The greater the proportion of fixed costs, the less flexibility an organization has to manage costs to weather a business downturn or loss event.

A corollary to this statement is the less understanding of costs effects and management capabilities, the less risk an organization should take. An example of understanding cost effects is the relation that advertising or promotion activities have with sales and the effect of a suspension of these activities. Management should understand the effect on revenue and net profit, as these expenses are cut for certain durations of time. Other costs can be understood in the same manner.

- As the level of uncertainty in an organization's socioeconomic and political environment increases, its capacity to take other risks declines (all other things staying the same).

This is simply a statement of preexisting risks facing the organization. The riskier the environment within which the organization pursues its performance objectives, the less risk it should take within its strategy and through its levels of financial and operating leverage.

Thus, an organization operating within a very stable, mature industry is able to take more risk in other ways (e.g., higher financial leverage) than one operating within a fast-paced, rapidly changing industry. Similarly, an organization with a stable political environment or stable social environment (i.e., society's beliefs, customs, practices, and behaviors) is also able to take more risk in other ways. The core environmental factors within its strategy and operating plans and approaches are unlikely to change and compromise its performance.

That being said, organizations within stable environments must monitor for emerging risks. These are risks that are unknown and not experienced before or known but changing in unexpected ways. Even a stable environment can be disrupted, as many industries and organizations have experienced.

Organizations can affect the first two of these risk-limiting factors by building capital reserves and/or changing the cost structure, but the last factor, the riskiness of the environment within which it operates, is beyond an organization's influence. However, management should pay attention to the environment to ensure that a previously stable environment doesn't become volatile and more limiting to the organization's ability to take risk. Certain environments become less volatile as markets, competitors, or other factors mature.

STRATEGY AND GOVERNANCE

With the organization's capability and capacity for risk understood, the organization must still identify and understand the risks inherent in its purpose and, through an iterative process, the risks introduced through its strategy. Earlier we noted that the organization can only take risks in support of its corporate strategy.

Organizational economics is about comprehensive recognition and understanding of the key elements affecting the business activities of the organization. Further, it is the market dynamics, competitor behavior, and social and demographic trends that further establish the key economics. All of these are what we consider to be performance drivers and, by extension, risk drivers.

The organization's strategy is about creating value for customers and claiming value for stakeholders. The organization's strategic position establishes a promise to meet the needs or solve the problem for a specific target market. Delivering on this promise to the target market clearly establishes a range of outcomes acceptable to the target market. Consequently the organization must have the risk capacity to ensure the range of possible outcomes can be managed to be consistent with the established risk appetite. Michael Porter has emphasized that genuine strategy must be unique to an organization11—that is, create unique value for a targeted segment of customers—and this would require a unique set of activities, and hence a unique set of risks. While not all may agree with Porter concerning uniqueness, most would agree that a good strategy is intentional and specific and hence would create a specific set of risks, ranging from creditworthiness of the targeted segment to operational risks related to delivering on the value creation. The leading strategy approaches, such as Porter's Five Forces, SWOT, PESTEL, and so on, can then be used to identify the risks specific to the value creation and positioning of the firm. Strategic and risk analysis have much in common.

WILLINGNESS TO TAKE RISKS

We have covered an organization's ability to take risk and outlined the linkage between strategy and risk taking. We need to consider an organization's willingness to take risks. This consideration helps differentiate risks. The establishment of strategy and corporate objectives has determined the types and aggregate level of risk that the organization will take, but the mix of risks and individual levels can be affected through an understanding of willingness to take risk.

Although the overall aggregate level of risk capacity and capability has been established based on earlier material, the level of individual risks must be fit within this. This is a balancing act and depends on risk-return dynamics and the willingness to take certain risks. To aid this discussion, we will differentiate between risks taken to earn an additional return and those risks necessary to the business and cost-prohibitive to eliminate.

If a firm is to create economic value, the risk must earn a commensurate return. Risks taken to earn a return are often the financial risks and this thinking is prevalent in financial institutions and by investors. Let's consider one financial risk—credit risk—that affects financial institutions and any other organization that offers payment terms to customers. This example can be extended to other risks taken to earn a return.

In a portfolio of accounts or loans receivable, there are a number of counterparties and each of these individually introduce risk. An organization can calculate the expected loss and unexpected loss from the portfolio and the revenue and capital requirements based on these calculations. Recall that expected loss flows through the income statement, and the product creating the possibility of loss must be priced to cover that possibility in addition to other costs. Further recall that the balance sheet needs to maintain sufficient capital to cover unexpected losses up to a defined and accepted amount. The organization can calculate the expected net income over economic capital to arrive at the risk-adjusted return on capital (either RORAC or RAROC). In combination, these two establish the ability to capture value from the taking of the risk.

The organization might pursue higher returns by taking on more risk. In financial institutions, this is done through lending to higher-risk individuals and companies at higher interest rates. In accounts receivable, this is selling on credit terms to a greater market base and accepting a higher level of bad debts. The level of risk taken depends on willingness and capability. For example, an organization may have the skills necessary to lend to sub-investment-grade borrowers but may not wish to be in that market with that level of risk. The organization decides on the level of risk to take based on its strategy and objectives, assuming it has the capability and capacity. The statement of risk appetite and tolerance for these types of risks, risks taken to generate returns, may be financial in nature. For example, a certain minimum risk-adjusted return may be required, with only a certain amount of value, earnings, cash flow, and/or capital put at risk by the activities (value at risk, earnings at risk, cash flow at risk, risk capital, and economic capital—brief definitions provided in Box 18.1).

A statement of willingness to take risks in qualitative terms helps establish the guidelines for risks that are difficult to approximate or measure.12 There are a number of examples that most readers will immediately recognize. Many regulated organizations would state that compliance with regulatory requirements is mandatory and that risk taking in this area is not acceptable. In today's world it is common to hear of the sanctity of the brand and reputation and most companies would not put these at risk. However, an organization may be willing to take a greater level of risk with respect to a competitor's reaction to a product or service pricing or placement strategy.

Many organizations use rating scales to capture their willingness to take risk. Included in these scales are the ratings against several statements such as preference, tolerance for the resulting uncertainty, selection of choice, and willingness and ability to trade off against other risk-taking activities. A sample scale is provided in Exhibit 18.2. The scale shown in the exhibit has been used at Hydro One and was the product of the development efforts of Rob Quail and his risk team.13

An example of a scale is the one that was developed within Hydro One, using Hydro One's language and understanding of risk and business terms. Hydro One's business is the transmission and delivery of electrical power to Ontario households and this business purpose is one of several business outcomes that influences the statement for Rating 3: “Preference for safe delivery.” Any organization deploying a rating system must ensure that it is designed for and appropriate to their business, fully understood across the organization, and that it is used in decision making.

To return to the risks associated with reputation, the rating may be at the most stringent level of risk taking (1 on the five-point scale in the exhibit) which would, for Hydro One, equate to reputation being considered “sacred” with an extremely low tolerance for uncertainty, an unwillingness to select any option that would increase risk to reputation, and that no trade-off between options would be considered if risk to reputation increases.

Previously we defined risk appetite and risk tolerance and suggested that each has a role to play in establishing an organization's thinking on risk taking. The two approaches provided here, the quantitative measures and the rating approach, can be used in the context of either. For reputation risk, the appetite and tolerance may be identical; for example, Rating 5 using the Hydro One scale. For other risks, the tolerance in certain circumstances and for defined periods of time may allow for greater risk than the risk appetite measure or rating indicates. The required circumstances, conditions, and documentation need to be clearly identified for the tolerance level to be taken if this approach is adopted. We provide examples later in this chapter when we discuss risk appetite and tolerance statement requirements.

Exhibit 18.2 Risk Appetite—Rating Scale

| Rating | Philosophy | Tolerance for Uncertainty | Choice | Trade-Off |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall risk-taking philosophy | Willingness to accept uncertain outcomes or period-to-period variation | When faced with multiple options, willingness to select an option that puts objectives at risk | Willingness to trade off against achievement of other objectives | |

| 5 Open | Will take justified risks | Fully anticipated | Will choose option with highest return, accept possibility of failure | Willing |

| 4 Flexible | Will take strongly justified risks | Expect some | Will choose to put at risk but will manage the impact | Willing under right conditions |

| 3 Cautious | Preference for safe delivery | Limited | Will accept if limited and heavily outweighed by benefits | Prefer to avoid |

| 2 Minimalist | Extremely conservative | Low | Will accept only if essential and limited possibility/extent of failure | With extreme reluctance |

| 1 Averse | “Sacred”—Avoidance of risk is core objective | Extremely low | Will always select the lowest risk option | Never |

There are risks that organizations take because they are inherent in their business operations. These risks can be transaction processing risks, human or people risks, and many others. Many of these risks can be mitigated through management action or transferred through insurance.

The current example on business leaders' minds is cybersecurity and cyber risk. Costs are associated with the level of security embedded in systems, the level and frequency of testing undertaken, and the insurance purchased. These costs reduce the risk to the firm but also materialize the risk loss to some extent by making associated expenses certain. In short, an organization does not want to spend thousands of dollars to avoid improbable and infrequent losses of dollars and cents. Of course, in terms of cybersecurity, the losses can be large and, as is often said today, it is not if but when a loss will occur. Digital breaches and losses should be expected for organizations with digital assets and processes and many organizations retain some loss exposure to digital breaches. Any remaining exposure must be consciously accepted, and any insurance purchased, or other management actions taken, must carefully consider cost relative to the risk reduction.

WHICH RISKS TO KEEP

We previously considered risk capacity and capability and have now considered willingness to take risk. We have stressed that risks should only be taken in the context of the approved corporate strategy and to further the accomplishment of its corporate objectives. We have also stressed the need to capture value for risks taken and to consider cost-benefit dynamics in considering risk mitigation and management actions. The outcome of these activities is to develop a clear understanding of how risk taking affects strategic and financial performance and to actively select activities incurring risk to enhance performance. The combination of these activities with core organizational capabilities associated with strategic operations creates the competitive advantage organizations seek.

In an age of lists and summary statements, the following may be useful but cannot be considered without the context provided earlier in this chapter and throughout this book:

Only keep risks that:

- Are integral to the organizational strategy and the accomplishment of corporate objectives.

- Are understood throughout all areas affected by or dealing with the risk, including executive management and the board of directors.

- Create and capture value for the organization.

- Can be dealt with the application of an organization-appropriate risk process (identification, assessment/measurement, analytics and management, monitoring and reporting, and proactive response and planning).

- Are within the approved risk appetite and tolerance statements and conditions.

KEY ELEMENTS IN THE ARTICULATION OF THE RISK APPETITE AND TOLERANCE

An organization's risk appetite and tolerance statements provide a critical component of the organization's governance materials and must be reviewed and approved by the board of directors on an annual basis, or as conditions warrant, which includes changes in the organization's strategy, business operations, operating environment, or financial condition.

Fortunately, risk appetite and tolerance statements have garnered a lot of attention over the past few years. Every financial institution is expected to have one and most do. Many other organizations have also adopted this approach to explicitly recognize the risks being taken and managed. Several approaches have been developed by consultants and vendors and many articles have been posted on various media. There is no shortage of advice, paid for or otherwise.

There is a great deal of commonality in the frameworks and advice. Key elements of risk appetite and tolerance documentation invariably include:

- The concepts of risk capacity, appetite, and tolerance.

- Governance requirements in terms of policies, authorities, principles, and ongoing monitoring and reporting.

- Metrics, limits, and triggers linked to income and capital or other performance metrics for approved risk taking.

- Management plans for risk incident responses.

- Statements cascading from the organization level down to individual risk-taking operations.

- Communication requirements to ensure that all risk takers are aware of the organization's appetite and requirements.

Increasingly, good risk appetite statements begin with a statement meant to capture the strategy–risk relationship:

- [Organization] will only take risks in support of executing on its business strategy.

Also, increasingly, these statements explicitly address reputation and/or brand as a key part of the organization's identity and valuable assets not to be put at risk. Individual organizations may have specific elements of their brand that they identify as core and not to be put at risk. Food and pharmaceutical organizations may state that the health and well-being of their purchasers are central to their product offering and not to be put at risk. These statements, if clearly articulated, enhance brand identity and support decision making consistent with the brand.

There may be other risk-taking activities that could fit within the strategy and brand but are still not acceptable to the organization. Increasingly, organizations are concerned about environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors when considering business alternatives.14 For example, an investor may avoid a firm with a poor environmental record, or a financial institution may not lend to gun manufacturers or gun shops. A key document that provides clarity on risk taking is an organization's Code of Conduct or equivalent. This document is a key risk document outlining ethical conduct requirements.

The organization may also want to send a message to stakeholders through a specific risk statement identifying certain activities as inappropriate. For example, a financial institution may state that it does not take speculative positions in its market-trading operations.

The foregoing implies that the risk appetite and tolerance statements employed by an organization are key elements in the articulation of strategy and brand. They are also key authority documents. The board-approved statements provide management with the authority to act within the specific requirements and constraints consistent with the authorities granted through the approved strategy, corporate policies, and resource plans.

Implicit in the foregoing is the connection between strategy, risk, resource allocation, and performance. Resource allocation is provided through expense and capital budgets and human resource plans and these must be consistent with the risk appetite and tolerance statements. They affect the organizational capabilities and risk capacity and they directly impact organizational performance. An integrated performance, resource, and risk appetite and tolerance approach can be the mechanism to bring these planning activities together to provide the businesses with clear performance objectives and risk and resource allocations and constraints.

What might this look like? A few simple additions to the risk appetite and tolerance approach can provide the clear linkage required.

Organizations already have financially based return metrics and they employ them in business target setting and associated incentive plans. It is also well understood that any losses from realized risks first flow through the income statement and that strong, stable earnings is a powerful defense. The risk appetite and tolerance statement could include clear earnings and performance expectations to provide greater context to the risk taking activities, and financial metrics should include key risk elements. An obvious and easy approach is the already mentioned use of risk-adjusted returns (RORAC or RAROC) that work well for financial institutions. Other measures could be used to limit and monitor income or expense volatilities or others in use in other parts of the organization could be brought into the statement; manufacturing defects and customer satisfaction, for example.

This approach would then allow performance and risk monitoring to track the underlying drivers that affect earnings in a consistent manner. The reporting would provide a comprehensive view to the business leaders and would clearly indicate how changing one element affects the earnings and risk levels. Trade-offs would become clearer and strategic and day-to-day business decisions would be able to take all factors into account. This approach, if done appropriately, would also help identify and reduce risk, resource, and performance conflicts.

It is important to note that the risk appetite and tolerance statements are forward looking, consistent with performance objectives. The monitoring and reporting of the recent and historical outcomes is important to ensure that the organization stays within its authorized risk profile, but the greatest benefit comes from analyzing performance and risk drivers (often termed key performance indicators, KPIs, and key risk indicators, KRIs) and forecasting the range of future possibilities. This allows the organization to recognize increasing risk trends, possibilities of future limit encroachments, and opportunities to shift risk taking to advance particular strategic objectives. The risk appetite and tolerance statements need to provide the organization with the risk metrics to be met as the future unfolds.

Previously we noted that some risks can be approximated using quantitative approaches and others can only be assessed qualitatively.

The financial risks are most able to use quantitative metrics. Examples include cash-flow coverage, financial leverage, and operating leverage requirements as well as value and earnings volatility constraints from market prices and yields. Other risks can also use quantitative metrics such as transaction processing errors and manufacturing defect limitations.

Some metrics are only indicative of the underlying risk, but they can still add value in expressing desired outcomes and acceptable limits. While metrics may be employed, these are qualitative approaches. The level and change in employee engagement scores, trust barometer scores, and staff turnover are three examples of HR metrics that are used to indicate the level of people risk. With respect to brand or reputation risk, an organization can monitor media sources and track the tone of the discourse relevant to its brand. Any limits established for this type of metric are really triggers or thresholds that demand management action.

For each identified risk within the organization, consistent with its strategy, there needs to be a statement of the appetite and tolerance for the level of risk. The statement needs to identify the risk clearly and not simply note a risk category such as people risk or credit risk. The objective potentially impacted by the source of the risk should be included and the acceptable (risk appetite) and maximum (risk tolerance) level of risk allowed. Exhibit 18.3 shows an example of a statement for a liquidity risk component.

Exhibit 18.3 Risk Appetite and Tolerance Sample Statement

| Performance and Risk Driver | Purpose | Appetite | Tolerance | Link to Strategy | Risk Manager |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90-day cash-flow coverage ratio | Maintain adequate liquidity to meet current cash flow obligations | 125:100 | 105:100 | Must maintain access to supply chain and production to meet market demand | Corporate Treasurer |

This limit employs what should be a clearly defined term: 90-day cash-flow coverage ratio. The organization must have this term defined and readily available and its calculation clearly stated to ensure that it is fully understood and that its monitoring and reporting are consistent over time.

It is important to re-emphasize the integrated nature of risk limits. This limit may appear to stand in isolation, but it must be consistent with financing policies and approaches, including accounts payable treatment and late payment processes, sales objectives and credit terms, and investment objectives and approaches. There may be other limits upon which this limit is dependent, such as the credit quality of counterparties allowed credit terms and the ratings requirements for short-term investments. All of these need to be developed together to result in mutually supportive risk taking across the organization.

The limit statement includes identification of a risk manager. This is the individual with the responsibility to ensure that the organization stays within the board-approved appetite and tolerance for this specific risk. This is the beginning of the cascading of limits, authorities, and responsibilities. Whether any cascading is the responsibility of the board can be considered philosophical in nature. In some organizations, the board delegates authority and responsibility to the chief executive officer (CEO), who then delegates to the executive team consistent with mandates and departmental roles. Department objectives are then developed to fulfill respective mandates. Using this approach, each executive leader would receive its own risk appetite and tolerance statement, and this would be further cascaded down into the departments under that executive's purview.

It is important to note that in successful, high-performance, and risk-mature organizations, every executive, every corporate function, may receive a risk appetite and tolerance statement, including the CEO. A CEO's statement may articulate responsibility for the formulation of strategy, ensuring that the executive leadership is sound and effective, establishing and maintaining a strong and healthy corporate culture consistent with the organization's values, and establishing the day-to-day operational requirements to ensure execution of its strategy, the accomplishment of its corporate objectives, and the establishment of an appropriate organizational culture consistent with its values. The appetite and tolerance requirements and limits would then follow directly from this role statement.

To further illustrate, there may be a statement for strategic risk and compliance that documents the CEO's responsibility for establishing and recommending for board approval the strategic plan and ensuring that it aligns with legislative and regulatory requirements and company bylaws. The limit statements may then provide a preferred level of risk (risk appetite) for strategic risk to be very low in terms of probability of causing material financial, operational or reputational loss, or exposure due to lack of compliance with legislative and regulatory requirements. It may even be very specific and state that there is no appetite for this type of compliance risk. The risk tolerance statement may simply state that no deviation from risk appetite is allowed.

Similar statements can be developed to provide clarity of risk appetite and tolerance for each of the roles and responsibilities maintained at the CEO level—executive team performance, organization culture, and so forth.

While the board delegates authority to the CEO to take risks, it too takes risks that cannot be delegated and, therefore, the board should have a clearly articulated risk appetite and tolerance statement. Exhibit 18.4 shows a sample board risk appetite and tolerance statement constructed for a moderately sized organization. This statement must be consistent with the board of directors and committee mandates and is meant to complement those with clear risk authority information.

Exhibit 18.4 provides a narrative approach to providing a risk appetite and tolerance statement and captures the appetite and tolerance using broad risk categories such as strategic risk. However, the description of the risk and the possible sources of loss bring the risk category down to the operating level. For example, strategic risk for the board is specifically related to the approving strategy in compliance with legislative and regulatory requirements (see Exhibit 18.5).

Communication of the statements is critical to success. The reader of the risk appetite and tolerance statement relevant to their area of responsibility should be able to readily discern the strategic intent, authority provided, and the constraints on levels of individual risks and aggregate risk. The reader should also be able to clearly relate to the statement and connect it to performance targets and expectations.

Communication is not a one-way street. The statements must be communicated down the organization, and those closest to the business and risk taking must communicate up, to support effective risk identification. The front line will realize that risks are changing or increasing more quickly than those higher in the organization and particularly those in support functions. The front line is also the best place to identify emerging risks. This two-way communication ensures that the organization always has its most important, most changeable, and most threatening risks included in the strategy-risk conversation and its day-to-day business decision-making processes.

Functional Background

The members of the Board of Directors (the Directors) have overall oversight responsibility for the operations of [organization name]. In their role they are, individually and collectively, responsible for reviewing, assessing, and approving [the organization's] strategy, ensuring that the executive leadership is sound and effective and establishing the governance requirements to ensure that [the organization] executes on its strategy, accomplishes its corporate objectives, and establishes an appropriate organizational culture consistent with its values.

Exhibit 18.4 Risk Appetite and Risk Tolerance—Board of Directors and Board Committees

The Directors are responsible for establishing and approving [the organization's] strategic plan and ensuring that it aligns with legislative and regulatory requirements and company bylaws. In approving the strategic plan, the Directors are responsible for strategic risk and elements of compliance risk for the organization as a whole.

Risk Appetite

The preferred level of risk for strategic risk is minimal in terms of probability of causing material financial, operational or reputational loss, or exposure due to lack of compliance with legislative and regulatory requirements. More specifically, the Directors have no appetite for this type of compliance risk.

Operational Risk

People Risk

The Directors are responsible for the hiring, evaluation, coaching, and, if necessary, firing of the CEO. They are also responsible for the existence and quality of the CEO succession plan. The capabilities, performance, attitude, and ethics of the CEO affect the performance, culture, ethics, and reputation of [organization name].

The Directors are accountable for people risk as it relates to the CEO.

Risk Appetite

The preferred level of risk for people risk is termed minimal in terms of probability of causing material financial, operational, or reputational loss or exposure. More specifically, the Directors have no appetite for this type of risk to [organization's] reputation, brand, or ethical performance.

Risk Tolerance

No deviation from the risk appetite requirements is allowed.

The Directors consider the following to be unacceptable in terms of this risk:

- A breach of the [organization name] Code of Conduct by the CEO.

- An adverse impact on [organization's] ability to deliver appropriate service levels or jeopardize service quality, integrity, or security standards.

- Potential occurrence of injury, harassment, or bullying to an employee of [organization name].

- CEO-approved business practices that may damage [the organization's] reputation.

- Loss of customer, intermediary, or regulator confidence in [the organization's] ability to conduct business compliantly.

- Incidents of legislative or regulatory noncompliance.

Exhibit 18.5 Strategic Risk and Compliance Risk

SUMMARY OF KEY ELEMENTS

The foregoing material links risk appetite statements to an organization's strategic purpose and process, organizational capabilities, and risk capacity and governance structure. The narrative can be summarized into several key elements for risk appetite and tolerance statements. However, this summary should always be considered within the context of the material provided.

The organization's risk appetite and tolerance statements should:

- Clearly link to the organization's strategy and corporate objectives.

- Reflect the organization's culture and values.

- Be aligned with specific business and operational activities.

- Be integrated with performance metrics.

- Be enabled by the organization's resource planning and allocation.

- Be enabled by organizational capabilities.

- Be appropriate given the organization's capacity to take risk.

- Be clearly expressed and communicated throughout the organization.

The reader of a risk appetite and tolerance statement should be able to discern, without too much effort, the organization's or functional area's strategy, objectives, business model (approach to executing the strategy), and authority to take risk, both type of risk and amount of risk.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

James Darroch is the CIT Chair in Financial Services at the Schulich School of Business, York University.

He teaches strategy and risk management with an emphasis on financial institutions. His book, co-authored with Pat Meredith, Stumbling Giants: Transforming Canada's Banks for the Information Age (Rotman UTP Publishing, 2017), was the winner of the 2018 Donner Prize.

James is married and has a son.

He holds an MBA and PhD from the Schulich School, where he has taught for over 30 years.

David Finnie has over 20 years of executive leadership experience in finance, risk, and strategy in global financial services organizations.

He has held senior leadership roles in Central 1 Credit Union, Global Risk Institute in Financial Services, American Express Company, and Bank of Montreal.

David is married and has three adult children.

David has an MBA, with a specialization in Finance and Financial Accounting, from the Schulich School of Business at York University and a Bachelor of Arts (Honours) in Economics from Western University.

NOTES

- 1. Frank Knight (1885–1972) was an American economist, one of the founders of the Chicago School, the Morton D. Hall Distinguished Service Professor, Emeritus, of Social Science and Philosophy, and the recipient of the American Economic Association Francis A. Walker Award. Knight is best known as the author of the book Risk, Uncertainty and Profit (1921), based on his PhD dissertation at Cornell University.

- 2. Some risks are managed down to what are considered (sometimes incorrectly) immaterial levels. An example would be a mining company: It can create great safety measures and oversight, but it cannot remove the entire safety risk at a reasonable cost. Some risk is left and becomes a cost of doing business that is not explicitly priced.

- 3. ISO Guide 73, Risk management—Vocabulary.

- 4. Carol Hansell, “Understanding the Directors' Duty of Care,” Module I of the Directors Education Program, Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto.

- 5. Harry Markowitz, “Portfolio Selection,” Journal of Finance 7, no. 1 (March 1952): 77–91.

- 6. Expected loss is the average loss predicted to occur using historical loss analysis in normal business conditions over a specified period of time.

- 7. Oldrich Vasicek, “An Equilibrium Characterization of the Term Structure,” Journal of Financial Economics 5, no. 2 (1977): 177–188 introduced the Vasicek Model and led to the creation of KMV by Stephen Kealhofer, John McQuown, and Oldřich Vašíček.

- 8. Franco Modigliani and Merton H. Miller, “The Cost of Capital, Corporation Finance and the Theory of Investment,” American Economic Review 48, no. 3 (June 1958): 261–297.

- 9. Unexpected loss is the potential for loss above expectations due to extreme events and is often expressed as the average total loss above the expected loss, using a defined confidence level.

- 10. Tier 1 capital was introduced in the 1988 Basel Capital Accord, International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards, Bank of International Settlements (July 1988, updated to April 1998).

- 11. Michael E. Porter, “What Is Strategy?” Harvard Business Review (November–December 1996).

- 12. We want to be careful with expressing risks as measurable—the outcomes from risk taking occur in the future and part of our premise is that the future is uncertain. Risk measurements are based on historical performance and assume the future will look like the past. As we have seen countless times, this is a weak assumption.

- 13. Rob Quail, “Defining Your Taste for Risk,” Corporate Risk Canada (Spring 2012): 24–30.

- 14. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors measure the sustainability and societal impact of an investment in a company or business.