Appendix A

A Case Example of Applying the Model to an Individual in a Development Program

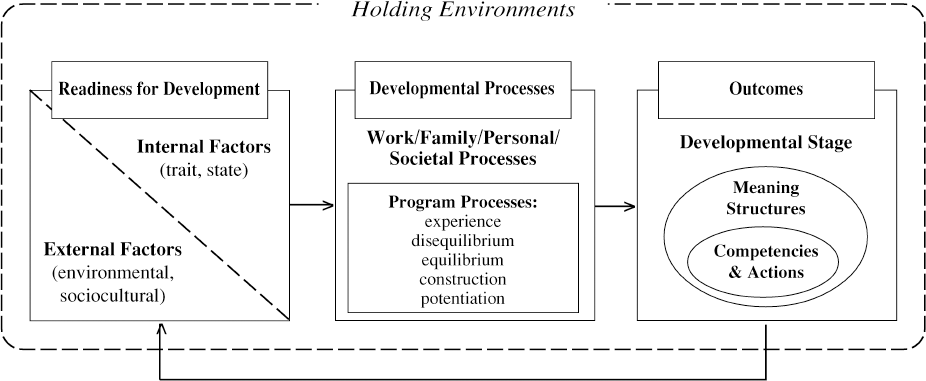

To illustrate how elements of our model (see Figure A1)—readiness, developmental processes, and outcomes—play out in a leadership development program, we use examples here drawn from a program offered by the Center for Creative Leadership. LeaderLab® (see Burnside & Guthrie, 1992; Young et al., 1993) is a six-month-long, extended-contact program. It begins with one week of class time at the Center, followed by three months of action and application at the workplace. Participants then return to the Center for another week of class time, followed by another two and a half months of action and application.

Throughout the six months a Center-employed “consultative coach” called a process advisor is assigned to work one-on-one with the participant. Participants also select a co-worker, called a change partner, to assist them as they implement action plans developed in the program. A guiding idea of the program is “head, heart, and feet”—indicating the values of an intellectual understanding of one’s leadership situation (“head”), an emotionally satisfying integration of life pursuits (“heart”), and appropriately changing behavior and taking action (“feet”).

The case materials we use below have been disguised to ensure confidentiality.

Tony Smith is a senior manager in a manufacturing organization we will call ABC Co. In what sense was he ready—or not—to participate in LeaderLab?

ABC had reorganized in order to emphasize team, rather than individual, performance. Smith did not have the requisite team skills or attitudes. He was, in fact, the opposite of a team player: abrasive, aggressive, always setting things up for a win-lose situation so that he could win. He would do his homework up to the wee hours of the night in order to hammer one of his peers the next day at a meeting. He had gotten a lot of feedback about this, from his boss, from his team, and from an internal consultant. His boss would not support Smith for any advancement in the organization. Smith was also in some personal pain, having been estranged from his two adult children for several years. He had tried psychological therapy. Things really weren’t working for him and he knew it. He had tried to change without much success. Before the program, he said, “I feel as if this is make-it-or-break-it time.” He was very explicit about what he needed to work on and why.

In Smith’s profile we can see a high level of readiness to engage in developmental work. His considerable ambition had become painfully bounded by his habitual behaviors and attitudes. His work environment offered a certain level of affirmation about his accomplishment. The environment provided adequate feedback and support but demanded further development. His company was being fairly clear that it was serious about expecting a new set of team competencies as criteria for advancement. He was at an age—forty—when society almost expects a psychological transition. Smith himself had become more open to change and had expressed willingness to do hard work, to “make it or break it.”

Experience. LeaderLab is experiential in two ways. First, it uses the participants’ worklife and, to some self-selective degree, personal life as its materials for action and reflection. For example, each participant receives the results of 360-degree feedback (from peers, superiors, and subordinates) early in the program; this informs an action plan that is then tested in the workplace and revised during the second in-residence session of the program. Second, it uses self-contained experiential elements. For example, participants are selected to represent a diversity of backgrounds. Coupled with elements emphasizing group interaction and self-expression, this typically leads to the kind of comprehensive engagement of values, attitudes, assumptions, and so on that signify experience.

In the case of Tony Smith, although he had heard some of the critical messages given in feedback to him before, the program provided the support necessary to reflect on them. He was able to bring the issues contained in his feedback into the events of the program, to reflect and work on the issues, thereby turning those events into valid developmental experiences.

Participants are asked to keep journals when they return home, and Tony Smith would sometimes stay at his office until midnight journaling. He overdid it, just as he did everything else in his life, but he was still able to use that tool to see what was going on with himself. For example, in this journaling he wrote about his wife’s concern that he was changing and that she didn’t feel part of the change process. The process of development in programs can be expected to interact with meaning-making in real-life experience. As in many such cases, Smith’s spouse was drawn into the dynamics of the leadership development program.

Disequilibrium and equilibrium. Tony Smith entered LeaderLab with a high level of pain and anxiety. Fear became added to these emotions as he began the program work. The case observer reported that “it was real frightening because the changes he was working on were changes that were affecting him at home too.” Tony Smith also found a variety of sources of equilibrium in his development work. The LeaderLab process advisor is a kind of personal coach. In Tony’s case, that relationship came to work fairly well: affirming him, encouraging him, helping him to remember what his strengths were—not just focusing on his weaknesses.

Construction. Tony Smith was working on constructing his world in new ways—that is, he looked at the ways he thought about and engaged his world and how those might evolve. One of these was a nagging sense of his own inferiority. With his process advisor, Tony worked out a more balanced self-appraisal that helped him think about his strengths and weaknesses in a more hopeful way. In order to make and sustain changes, he had to look at his role in the organization differently, and he had to understand what a team really is. This involved giving and getting information in new ways. In the words of the case observer, “He flew around the country and met one-on-one with every peer, and he actually said to them, ‘This is what I have learned about myself in going through this process. Here’s who I really am; here are the things that I am trying to work on, that I have made a commitment to try and change. I need your help in that process. Will you work with me? Will you give me feedback? Will you call me on it when you see me doing the old behaviors? Are you willing to be a partner? I really need you.’”

Potentiation. Like many program participants, Tony reverted back to his “old ways” in the months after the program. Underlying meaning structures are slow to change. With respect to potentiation, the key question is: “Has a seed been planted, and is the seed alive and growing?” In talking with Tony a year later, we saw an enhanced potential for further development: “I’m still hard on people in meetings too often, but I catch myself. Sometimes I catch myself during a meeting, and I back off. Before, I had no idea, really, of my harsh effect on people. Now I have this bigger idea about how teams work and that excites me, even though I don’t always live up to it. It makes sense to me now. I think I’m making progress.”

Using the model, we can see a set of nested outcomes for Tony. At the broadest level, Tony is working on a new stage of development. This stage is one in which his relationships are no longer automatic but rather are based on a clearer self-identity and an honest sense of his own strengths and weaknesses. Within this new stage, Tony is able to use the meaning structure of teamwork: that is, he sees himself as being able to make informed choices about his roles and the way he relates in teams. At the level of actions, Tony has become less impulsive. He asks more questions in meetings. A year later, one peer said to us: “He no longer bangs his fist on the table and shouts ‘This is how it is!’”

Figure A1. Leadership Development Program Model

Source: Evolving Leaders: A Model for Promoting Leadership Development in Programs, by Charles J. Palus and Wilfred H. Drath. Copyright ©1995 by Center for Creative Leadership. Permission to reproduce and distribute this figure, with © notice visible, is hereby granted. If it is to be used in a compilation that is for profit, please contact the publisher for permission.