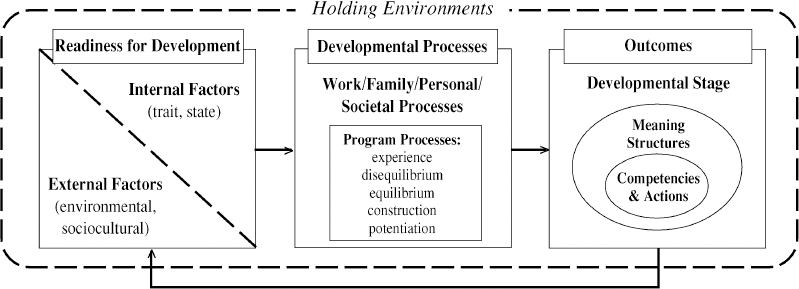

The model we offer (see Figure 2) shows a cyclic process of three time-linked categories: readiness for development, developmental processes, and outcomes. At first glance these categories might not seem different from those used in training for the learning of specific content. As we discuss the makeup of these categories and their processes, it should be clear that we are concerned not so much with imparting skills but with the evolution of more encompassing and adaptive meaning structures.4

The term readiness for development refers to a simple and important observation: There are developmental differences among people entering leadership development programs, and within an individual at different points in his or her life. The basic diagnostic question for readiness is, “What kind of developmental work is each person best prepared to do?” Or perhaps, “Where are they at, what do they need, and how do they need it?” Adding to the complexity introduced by this basic observation is a related point: There will be cultural differences in the supportiveness of the home environments (organizational, familial, societal) for these differing developmental positions. And this: Some people will be well-prepared to engage a potentially stressful developmental experience; others will not be ready for additional stress in their lives. Some strategy for comprehending and handling diverse needs within the program context, including screening and sorting participants, is necessary.

We propose four types of readiness factors: trait, state, environmental, and sociocultural. Trait and state refer to a person’s internal condition. Environmental and sociocultural refer to a person’s external milieu. Table 1 lists selected factors we propose for each type. Two cautions are in order. First, although it can be useful to focus on the role of various specific readiness factors—as a diagnostic strategy, in research, or in a process of programmatic feedback—it must be kept in mind that the diagnosis of readiness involves a consideration of the pattern which is emergent from the totality of factors—that is, consideration of the “whole person”—rather than of abstract factors taken one at a time. And, second, there is typically a great deal of interdependence among these four types of readiness factors, and distinctions among the types are not always clear-cut. For example, a person’s age is a state that is laden with sociocultural significance. This typology is meant to be a heuristic device with which to draw more elements into a perception of the patterned whole.

Table 1. A Selected List of Proposed Developmental Readiness Factors

INTERNAL |

|

Trait |

State |

enduring character |

developmental stage |

chronic problems |

stability of life structure |

life-story |

|

age |

|

satisfaction |

|

acute problems |

|

EXTERNAL |

|

Environmental |

Sociocultural |

holding environments: work, family, community |

developmental norms: age, gender, race, class, ethnicity |

job challenges stressful events |

social milieu / world events and conditions |

fortuitous events |

|

Our present understanding of readiness is far from complete; diagnosis of readiness is still more of an art than a science. The following discussion is selective and often speculative. We invite readers to build on our understanding.

Trait readiness factors. By traits we mean relatively enduring psychological characteristics of the individual. Traits typically don’t change much over time, although the way a trait is expressed is subject to learning and development. For example, introversion/extraversion is an enduring trait dimension, and introversion is identifiable in infancy and tends to persist throughout adulthood (Kagan, 1971; McCrae & Costa, 1984). However, an introverted person may learn to moderate introverted behavior as appropriate, and may become adept at, and more valuing of, extraverted behavior.

What “character” is and how enduring it is is a matter of many alternative definitions and much debate. William James (1890) saw it as that which is “set like plaster” by about age 30. Freud held the die to be cast by age seven or so, the routine fate of adulthood being to relive early patterns. Much developmental theory is at odds with the more extreme versions of “plaster theory.” What we are interested in is how a person’s character traits affect the development of meaning-making—the substantial aspect of a person which need not harden.

Kaplan (1990, 1991) and his colleagues (Kaplan, Drath, & Kofodimos, 1991) have described a trait that is apparent in high-achieving executives called expansiveness: an aggressive need for mastery and the urge to “expand” one’s domains. A kind of readiness is revealed in the observation that expansive executives tend to become elevated and isolated by their position, such that they become insulated from valid and useful feedback from others. Thus, an effective intervention has been to flood the individual with data in a supportive yet challenging program context so that any case for change is made comprehensively and convincingly.

Drath (1990) argued that expansive executives tend to be in what Kegan (1982) has called the “Institutional Stage” of development (a stage that features a strong sense of individualized personal identity). Thus strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities for growth derive from a developmental logic that includes “expansive character” as but one element. In this view, some aspects of character that appear to be set in plaster are in fact plastic, and there is the potential for further development.

Palus and his colleagues analyzed the case of Dodge Morgan, a CEO who quit his job in order to pursue his dream of sailing around the world alone. The authors looked at the circumstances that led this consummate expansive into—and then away from—meaning structures oriented toward individual achievement (Palus, Nasby, & Easton, 1991). A life-story perspective (mentioned below) was used to examine readiness in this case study.

A trait that shows promise as a readiness factor is called openness to experience (hereafter referred to as openness). High openness is characterized by a flexible and inviting (hence “open”) approach to new ideas and new experiences. Costa and McCrae (1978) described openness as “marked by toleration for and exploration of the unfamiliar, a playful approach to ideas and problem solving, and an appreciation of experience for its own sake” (p. 127). Openness has been shown to be moderately correlated to the ego-developmental stage as measured on Loevinger’s scale (McCrae & Costa, 1990), and to the stage of moral reasoning as measured on Rest’s (1979) scale (Rybash, 1982). The trait of openness, at least in some modest amount, would appear to be favorable to the evolution of a person’s meaning structures.

Musselwhite (1985) described a constellation of traits, quite similar to openness, which contributed to increased “readiness for learning” in a study of outcomes of a leadership development program. He used the descriptor “facilitator of change” to describe a person who is “innovative, ready to explore, plow new ground,” “not a defensive person who hopes to maintain the status quo” (pp. 79, 106).

But high openness is not necessarily desirable: “Individuals [with] excessively high levels of openness may be so easily drawn to each new idea or belief that they are unable to form a coherent and integrated life structure” (McCrae & Costa, in press, p. 31). It does appear that some capacity for openness—and a modest capacity may be sufficient—must be mobilized or “spoken to” during a leadership development program.

Interesting research questions abound: Can openness itself be changed by a transformative experience (Palus, 1993)? Does openness promote the examination and revision of imperatives from childhood (Gould, 1978)? Are open individuals more likely to periodically reshape their life structures (Levinson, Darrow, Klein, Levinson, & McKee, 1978)?

The literature of psychology is filled with descriptions of afflictions that often prove to be more-or-less enduring traits—one might consider these chronic problems—which play havoc with the individual evolution of meaning structures. Chronic schizophrenia is an extreme example of a persistent impairment that is likely to interfere with leadership development. A discussion of this literature, however, is beyond the scope of this paper. Some screening method for severe psychological problems (such as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, interpreted by a trained clinician) is appropriate when the methods of the program are particularly stressful, prolonged, and intrusive.

We have just scratched the surface with respect to traits and readiness. Any dimension purported to be an enduring psychological trait may conceivably be viewed in relation to readiness—that is, in relation to where the person is and what he or she needs developmentally. However, the research relating traits to developmental readiness is sparse. The best approach may be a clinical one in which rich data is collected with an effort to understand the whole person, including how one’s enduring traits affect evolving structures of personal meaning, as well as the collective meanings in which the person participates.

State readiness factors. State readiness factors are changing characteristics of the individual that influence readiness for development. While the term trait emphasizes the “entity” or constant aspects of individual being, the term state emphasizes the “process” or changing aspects of individual being. Because development is itself a process, it is more directly dependent upon state than trait readiness factors. Indeed, as Table 1 indicates, there are more state factors than trait factors that can currently be identified as pertinent to developmental readiness.

Developmental stage is itself an important readiness factor. There is merit in the idea of targeting a program to a stage-homogeneous (or roughly so) audience, so that common issues can be addressed directly. Alternatively, deep differences in stages among participants in a program may itself be used as a source of the disequilibrium (see below) necessary for development.

William Perry’s (1970, 1981) scheme of developmental positions (or stages) has been used extensively, especially with college learners, to stretch—but not deny—the epistemology (or meta meaning-structure) of the learner (for instance, Moore, 1989).

The stability of one’s stage of development is a readiness factor. For example, a person may be in an unstable developmental state by virtue of just entering or just leaving a stage. Developmental needs at each of these points are quite different: A person entering a stage cautiously embraces perspectives that a person leaving that stage repudiates (Lahey, Souvaine, Kegan, Goodman, & Felix, 1985). Appearances may be deceiving: A person might appear, to themselves and others, to be in a stable developmental position but in fact be ripe (with respect to other readiness factors) for substantial change. Obvious disruption, such as a major job change or crisis, divorce, or an illness, may be an opportunity for the restructuring of meaning. Because a crisis includes danger as well as opportunity, it is not enough to notice a state of developmental stability or instability without reference to the whole picture, as partly revealed by other readiness factors.

The state of satisfaction with various aspects of life may be understood as a readiness factor. Global dissatisfaction often indicates an opening for new perspectives. Satisfaction is often to some degree a barrier to new perspectives. But as with stability, a person may feel satisfied and yet by other indications (other readiness factors) be ripe for developmental movement.

Chronological age is related to readiness in two ways. Age is a gross predictor of stage, and some particular ages are associated with transition. Consider Erikson’s developmental schema, in which biological, psychological, and social demands intersect to produce stages with broad age norms. For example, the tasks of “the Generativity Stage” (such as producing, reproducing, and providing) typically fall into the middle decades of the life span (Erikson, 1963). The pinnacle of generativity is closely connected in our society with Kegan’s (1982) “Institutional Stage”—that is, seeing the world with the lens of a strong personal identity. Erikson’s final stage, “the Integrity Stage,” is identified with late-middle to old age, a time for review and integration, and taking on the roles of the elder—including the objectification and possible transcendence of personal identity. This meaning structure is similar to that of Kegan’s “Interindividual Stage,” suggesting that while it may be typically found in later life, it need not be limited to that age period.

Daniel Levinson and his colleagues (1978) postulated a number of age ranges in which transitions in life structure were likely (that is, ages 17-22, 28-33, 40-45, 50-55, 60-65). Palus (1993) found clusterings of transformative life experiences reported around ages 30, 40, and 50 and concluded that social expectations frame these “decade age markers” as a kind of developmental precipice, establishing in some cases a self-fulfilling prophecy for transition. Gail Sheehy’s popular book Passages (1976) has served to reinforce such expectations, making it even more likely that people crossing into a new decade will feel ready (or feel pressured) for development.

Lives are in many ways like stories, sometimes so much so that the “script” of one’s life story indicates periods of developmental readiness (Gergen & Gergen, 1987; McAdams, 1988). McAdams asserts that people know their own lives as stories. Some people are self-conscious about these stories, and some are able to sense the necessity of a new “chapter.” Or one might look at a person’s life story and see a history of development and infer that further development is likely. An individual’s personal theory of development is thus of interest to readiness (and it is an underexplored facet of life-story theory and research).

One aspect of personal identity as a story is what Levinson et al. (1978, p. 91) called “the Dream”: a “personal myth, an imagined drama,” “a vision.” Consider the dream of Dodge Morgan, the CEO who quit his job, built a boat, and sailed around the world, nonstop and alone. Morgan lived for twenty years with his dream, a promise to himself that he would someday make a “very significant sail alone with a boat built specifically for the job” (Palus et al., 1991, p. 16). Not only did Morgan’s dream culminate in a major transition in his external condition and his activities, but his meaning structures also appeared to undergo a profound shift—all in tune with an identifiable life story.

Finally, we wish to mention the role of some acute problem as a state readiness factor. A person who is temporarily under the malaise of severe anxiety or depression is not a good candidate for a powerful development program that deliberately introduces an element of disequilibrium into a person’s perspectives. Of course, such a condition may represent the disequilibrium of development-in-progress, in which case the person probably needs a “natural” or clinical therapeutic milieu (Kegan, 1982) rather than a leadership program.

It would be a mistake to look only at the internal, psychological condition of the individual when considering readiness for development. External factors are of substantial importance. We divide these external factors into the categories of environmental and sociocultural. The former refers to factors in the immediate environment of the individual. The latter refers to more general factors.

Environmental readiness factors. Developmental stages are more than just individually situated perspectives. According to Kegan (1982, p. 116), stages are “held”—validated, echoed, and supported in various ways—by holding environments, consisting of various milieus of the workplace, family, community, and society (see also Winnicott, 1965). The “individual” is more than that; a person is at the same time an “embeddual” (that is, one who is embedded) and made whole and buoyant and meaningful (or not) according to how well the holding environment is holding.

Meaning structures reside in the environment as well as in the individual. You can offer someone a new meaning structure, but structures are embedded in environments as well as in minds, and so environments as well as minds must change. This focus on development draws our attention not only to the workplace but also to other holding environments—other realms of meaning-making that might be able to support and affirm new meanings.

Well-functioning holding environments also “let go”—that is, they recognize and support development in the form of timely emergence and separation. For example, parents support their child within a web of relationship that defines his or her being. These same parents firmly insist that the painful separation of leaving home is to be endured in the face of various manifestations of loss of meaning (such as homesickness, religious crisis, and identity crisis). This separation eventually culminates in a new mode of self-authorship and autonomous identity, and their offspring finds new holding environments for this new meaning structure within specific work and social organizations.

Torbert (1987) reported that organizations seemed supportive, to varying degrees, of “Interpersonal” and “Institutional” stages (in Kegan’s, 1982, terms), as well as an intermediate stage Torbert calls the “Technician Stage.” The “Institutional Stage,” in which one is subject to the meanings of self-authorship and identity, appears to be currently upheld as an ideal by most organizations—and yet there is a growing need for the competencies supported by stages beyond this. Readiness for advanced development in individuals is thus facilitated by organizations—as well as by familial, personal, and community relationships—which have the ability to hold meaning beyond the “Institutional Stage.”

The significance of holding environments is paramount in our model of leadership development and not limited to readiness. We will revisit the concept of holding environments below as we discuss the processes and outcomes of development.

The nature of a person’s job challenges, particularly certain kinds of changes in type and degree of job challenge, contribute to readiness for development (McCauley, Ruderman, Ohlott, & Morrow, 1994). In a study of the self-reported outcomes of a leadership development program, Musselwhite (1985) identified a number of job-challenge-based readiness factors. Promotions and major changes in responsibility that occurred before the leadership development program were seen by participants as beneficial to the impact of the program, whereas the same events occurring after the program distracted from the impact of the program. In particular, moving into a management role for the first time, moving into an executive role for the first time, and being newly appointed as president or CEO typically required a substantial shift in perspective (see also Kaplan, Drath, & Kofodimos, 1985) and accentuated readiness for the program. Finally, Musselwhite identified a group that felt that readiness stemmed from a lack of a personally significant job challenge, including burnout and what has been described as a midlife identity crisis.

The occurrence of various kinds of stressful events can affect readiness in two possible ways. First, accumulated life stress might bring a person to the point where new meaning structures are embraced in order to cope (Lazarus, 1966; Taylor, 1989). However, the same amount of stress in another person might place them in a fragile state, one that does not warrant the additional stress of a developmental program. To our knowledge research has not been done that would resolve this individual difference, and again we suggest that this factor be dealt with in the context of all available information on readiness.

The second way in which a stress may influence readiness is as a single event which sends a person down a particular road of life’s possibilities. For example, being laid off from one’s job may lead to a new circle of friends and new holding environments. Bandura (1986) has called this type of event, when the outcome is favorable, a fortuitous event—that is, any life event (stressful or not) that opens up to a positive circumstance.

Sociocultural readiness factors. With the label sociocultural readiness factors we mean to draw attention to influences on developmental readiness that operate on a larger scale than the proximate environment of the individual.

Every society has developmental norms—ingrained standards, assumptions, rules, and expectations—for how, when, why, and to whom development (however defined) occurs. For example, the phenomenon of “decade age markers” discussed above points to a cultural norm which channels development. And we tend to make assumptions about what kind of developmental experiences are appropriate for old people versus young people—and what the age brackets of “old” and “young” are. Likewise, women and people of color have been subject to restrictions on their development based, partly, in assumptions about their potential. Recently, these restrictions have become more subtle but they have resulted nonetheless in “glass ceilings” and increased levels of poverty.

Thinking about developmental readiness requires that we examine such norms. We suggest that there are three ways in which developmental norms influence assessment of readiness. First, norms may produce undesirable barriers (for example, “glass ceilings”) that may falsely characterize people as “not ready.” Second, norms may accentuate feelings and perceptions of readiness in some cases (for example, “I’ll be thirty next year; it’s time to rethink my life.”). Finally, cross-cultural differences in developmental norms can deeply complicate the assessment of readiness: How can I, as a person from the United States, understand what development—readiness, processes, outcomes—means to a native of Japan?

Also, what we have labeled as social milieu influences readiness. By social milieu, we mean the larger context of events and conditions in the society. For example, in the United States, the current upheaval of economic restructuring affects readiness for development, albeit in ways we do not understand very well. The overall social milieu has changed; each corporate restructuring is no longer an isolated event but an aspect of a social movement. Having experienced years of this movement, we know that downsizing may lead to trauma in those laid off and to “survivor sickness” among those remaining (Noer, 1993).

One useful way to frame such trauma or sickness is as a “neutral zone” (Bridges, 1988; see also 1980), a period in which prior meaning structures have been disrupted and new ones have not yet been found or consolidated. Understanding the inherent pain and dangers, Bridges cites ways in which this neutral zone can—or must—be used as a period of creativity, reflection, and renewal. In assessing readiness for development, it would be useful to understand the nature of not only the particular individual’s neutral zone but the associated organizational and societal neutral zones as well. The challenges for those of us contemplating leadership development are enormous: For example, how might we assess readiness for development in light of the neutral zones in the former Soviet republics?

By developmental processes, we are referring to how development occurs. How do individuals and systems evolve the capacity to make more encompassing, adaptive, and sufficiently complex meaning? Our model focuses on a particular aspect of leadership development processes: individuals in programs. However, as the second box in the diagram of the model in Figure 2 illustrates, a leadership development program is embedded in a larger set of ongoing developmental processes with respect to workplace, family, social, and personal dynamics. Consideration of these “big picture” processes is vital in any developmental program aiming for a nontrivial impact on leadership.

According to our model, leadership development programs aim to provide an engaging experience, which produces disequilibrium in how the participants make meaning, which creates the potential for eventual reequilibration into a more encompassing and adaptive stage of being and behaving. A good program will provide and facilitate appropriate holding environments (including the functions of holding and letting go) for participants “where they are” (that is, the “old” stages) as well as for the emergent stages.

The program should provide support for an emerging set of meaning structures, while recognizing that the “new” equilibrium may be unstable, the often-tentative leading edge of a relatively slow and unsteady developmental movement. Thus, in our model, “regression” after the intervention is not necessarily seen as a failure of the intervention to properly transfer back to the real world. Rather, regression along with an increased potential for eventually stable new meaning structures is recognized as essential to the nature of developmental evolution. The recognition of this sort of potential is tricky, because potential is hard to observe, measure, or otherwise sense; this is where the readiness and outcomes portions of the model should prove useful.

According to our model, then, leadership development programs have five requisite, interwoven processes: experience, disequilibrium, equilibrium, construction, and potentiation.

Experience. Leadership development requires experience as one of its component processes. Experience as used here refers to circumstances that fully, broadly, and actively engage the person’s meaning structures. Experience utilizes—and challenges—the depth and breadth of our abilities to construe the past, present, and future. What we mean by experience excludes, for example, purely rote learning, skill learning divorced from context, and circumstances in which the person is substantially hiding, disguising, or disengaging his usual mode of being.

A trainer from the LeaderLab program explains it this way: “When you’re working with people’s real-life experience—to me this is a key—you invite people to bring their ‘real’ selves in. Now, what does it mean to bring their real selves in? Well, I would say that it has a lot to do with their real-life experiences being invited to be front and center. Unfortunately, I think sometimes in our educational efforts we invite people to set aside their life experience and to take in some kind of abstract model” (R. M. Burnside, personal communication, October 18, 1994).

The idea that development requires the full engagement of life experiences (see also Dewey, 1963; James, 1890; Kegan, 1982; Kelly, 1955) can be contrasted with the idea that development is the unfolding of innate capacities (as expressed for example by Jaques & Clement, 1991, who maintain that leadership capacities develop according to a trajectory established at a very young age, if not in the womb) or is merely the imprinting of information via the senses onto a blank slate (as seen in much textbook and lecture-based training that takes a checklist approach to appropriate competencies). It may seem obvious that development results from an intense interaction between inner capacities and outer realities (Piaget, 1954), but this has often been ignored. And although the unfolding and imprinting perspectives have their place, they have too often been used as the primary engines in the pursuit of developmental goals.5

Leadership development in our view requires that individual and collective abilities to make effective sense of what’s happening are at least occasionally stretched to the limit and beyond, in some context that provides for “holding” emergent new meaning structures. The trick for leadership development programs is to promote this kind of experience within the program constraints. Defining the role of the experience in this way puts such constraints in a new light, as illustrated in the case study in Appendix A.

Disequilibrium. Experience by itself is not enough for development. Everyday experience is quite often a rut—an engaging rut, to be sure, but a rut in that we tend to select and interpret experiences in line with our existing ways of understanding. The holding environment can conspire in this rut-making. Meaning structures tend to form self-confirming, self-sealing, apparently seamless wholes (Sullivan, 1953), rendering most experience familiar and tractable. However, the degree of clarity, and the apparent comprehensiveness which this condition provides, tends to preclude the evolution of new forms of meaning at more comprehensive and complex levels of adaptability—our definition of development.

Structures of meaning maintain equilibrium by efficiently assimilating and accommodating new experiences. Assimilation means interpreting new experience to fit one’s existing meaning structures. When an experience does not fully assimilate, the meaning structures may accommodate; that is, they may stretch their forms (sometimes only temporarily) to take in the experience (Block, 1982, p. 286).

The metaphor Piaget used for equilibration is digestion: food (or an experience) is chewed up to fit the “digestive tract” of the organism (assimilation), while at the same time the “digestive tract” stretches and changes its “chemistry” (accommodation). At the conclusion of “digestion” the experience has been dealt with, and the person remains in balance without having changed in any substantial way. The belt comes out a notch but everything still fits, more or less. Minor accommodation acts to preserve rather than transform the essential structure.

Disequilibrium occurs when this routine of assimilation and accommodation becomes turbulent. The person attempting to take in an experience gets “indigestion.” The experience will not assimilate into the person’s existing framework, even with some stretching of the framework. Yet it cannot be completely rejected as nonsense (labeling something as nonsense is a form of assimilation). The facts don’t behave. They don’t all add up. Meaning gets patched together, whereas before it was seamless. The experience is one of loss of meaning, or confusion, and is frequently accompanied by feelings of threat, anxiety, and pain. There may be anger at the messenger or agent of the offending material. Interestingly, developmental disequilibrium may also sometimes be experienced as exhilarating, as some combination of relief and the sense of the onset of new possibilities.

This state of disequilibrium can be a most creative state, leading to the potential for fundamental development (Bridges, 1988; Kelly, 1955; Mezirow, 1991; Palus, 1993; Perry, 1981).

There are few experiences in the biography of a man more distressing than that of feeling himself utterly confused…. The more deeply the confusion enters into my life the more alarmed I become….

Yet almost everything new starts in some moment of confusion. In fact, I cannot imagine just now how it could be otherwise. But this is not to say that confusion always serves to produce something new. It can just as well have the opposite effect, especially if the person finds the confusion so intolerable that he reverts to some older interpretation of what is going on….

But there is another stage in the creative process that stands midway between the confusion that we try to dispel by seeking either something new or regressing to something old, and the structured view of our surroundings that makes it appear that we know what’s what. It is that transitional moment when the confusion has partly cleared and we catch a glimpse of what is emerging, but with it are confronted with the stark realization that we are to be profoundly affected if we continue on course. This is the moment of threat. It is the threshold between confusion and certainty, between anxiety and boredom. It is precisely at this moment when we are most tempted to turn back.

Let us concentrate on this moment of threat—or these moments of threat—in the life of man. Let me suggest that if we can find some way of helping man pass this kind of crisis we will have helped him in one of the most important ways imaginable. (Kelly, 1969, pp. 151-152)

Equilibrium. Thus far we have established that leadership development programs provide experiences that disequilibrate meaning structures. Yet the experiences of living also do this (Kegan, 1982)—sometimes quite thoroughly in these days of organizational restructuring (Bridges, 1988; Noer, 1993)—and people often come to programs in considerable disequilibrium. The artful task of a program is to provide disequilibrium when necessary but also to provide timely and appropriate support and balance (equilibrium). This means appropriately affirming existing modes of being, as well as affirming newer, potentially more adaptive modes of being. A leadership development program thus has the difficult task of being a holding environment for both the old and the new, as well as acting as a medium of disequilibrium.

Not all developmental programs should be oriented toward the next stage of development. Piaget warned against the urge to accelerate the advent of the next stage (he called that urge “the American question”). Some participants in leadership development programs will have as their greatest developmental needs the affirmation and the continued exploration of their current stage of development. For example, a person at Kegan’s (1982) “Institutional Stage” may still be building an autonomous identity and will need support in building awareness and confidence about the meaning structure of personal identity. “Going against the grain” as a learning strategy (Bunker & Webb, 1992)—that is, experimenting with experiences that appear to be counter to our own identity—must come after (or alongside) going with the grain—that is, learning in support of identity, “in line with” our character. “With the grain” learning is perhaps less likely to be an unsettling event than it is to be part of a flow along the lines of underlying strengths and proclivities. Although strengths that are used to excess eventually become weaknesses (McCall, Lombardo, & Morrison, 1988), developmentally it is necessary to first acquire those strengths.

Construction. Experience, equilibrium, and disequilibrium provide the necessary processes and contexts for development. What one does with these is critical. Simply experiencing, sensing, knowing, feeling, or reacting is not enough. Attention to the processes of making sense—making meaning—is essential.

Developmentalists know something now about how to join the environment to stimulate development; but have we learned how to join or accompany the meaning-maker when he or she faces a world that is already heated up, already stimulating, even to the point of being meaning-threatening?

The greatest limit to the present model of developmental intervention is that it ends up being an address to a stage rather than a person, an address to made meanings rather than meaning-making. (Kegan, 1982, pp. 276-277, emphasis in original)

We believe that requisite leadership capacities for facing emerging challenges include the ability to take alternative perspectives and the ability to create, shape, and negotiate changed perspectives, both for oneself and within one’s community (see the “Outcomes” section of this paper for more on this). In order to do this, one comes to an awareness that the imposing and seemingly unambiguous truth and reality of the world are substantially the result of our constructed perspectives, paradigms, and frameworks—and that these perspectives are not final but potentially open to various kinds of rebuilding.

Development is a journey; let’s take a look at two highway signs. One is “Pedestrians Cross Here.” Bridges (1988) points out that changing to a new set of meaning structures is often treated as if it were crossing a street and the goal only to get quickly to the other side. A more appropriate sign from our view is “Under Construction.” It would be a mistake to think that the end is attained by crossing the street. There will always be streets to cross. Rather, adeptness with construction—with consciously visioning and revisioning, framing and reframing, personally and in community—is the real prize of leadership development.

Potentiation. Development, we believe, is not necessarily a uniform, linear, unidirectional progression through a sequence of meaning structures.6 It has at least a bit of the swirling, stuttering movements that systems theorists have referred to as chaos (Wheatley, 1992). A linear motion would be the following: A person has a perspective, disequilibrates, and then finds a new and stable equilibration and a new perspective. More likely, a person disequilibrates, has some glimpse of or experience within a new perspective, and then returns to his or her original perspective—but with a greater potential for future movement along this newly created “fault line.” Potentiation refers to the increased possibility of future sustained change in meaning structures. The person has been sensitized to the possibility that a meaning structure can in fact lose its ability to “make sense.” Continued experience in the vicinity of this fault line increases the chances for additional glimpses of the new perspective until, eventually, a new structure of meaning develops and a new equilibration results. This will probably not happen as a result of a single leadership development program, of course. Such programs must be seen in the context of the overall role they play in a stream of disequilibrations that will be different for each person.

The loss of the glimpse of “a new meaning” may set up a kind of yearning to reengage the process of development. The experience of disequilibrium and reequilibration that are undergone in such an intervention often become a memory after a program, but a memory with important consequences for further evolution in the system of meaning-making. It can be part of the leading edge of a growing awareness of the possibility of a new, more adequate way of knowing. It is an important link in a chain of events that makes it successively more likely that a new way of knowing—and hence a new way of acting in the world—will be found. Perhaps, then, part of a program’s power to foster development may be related to its power to stay in the memory.

William Perry (1970) offered an intriguing slant on developmental-stage potentiation in terms of a process he calls “the Trojan Horse.” Perry observed that the Harvard undergraduate students he was studying would tend to make the transition from a comprehensively dualistic mode to a comprehensively relativistic mode7 in a particular manner. Their professors would not reward their characteristic stage of “tell us the True Facts we should learn” (dualism) with good grades, instead requiring that they analyze and critique the utility of a variety of viewpoints (relativism). He also observed that at first the students would use relativism as a specific tool to approach assignments and tests for the purpose of getting a grade. Often they would use this tool quite well, albeit with cynicism. Their broader worldviews remained distinctly dualistic. Over the course of a year or two, however, the relativism would come out of where it had been lying in wait (as if from a Trojan Horse) and overcome the city. That is, the students would become relativistic in many of their affairs, scholarly, civic, relationships, and so on.

Thus, we extend the concept of potentiation to include the Trojan Horse. The “glimpse” of a new stage may be in the form of a useful tool, even if the stage represented in the tool is at first viewed with suspicion.

A leadership development program, to be most effective, should take some responsibility for actualizing the potential it creates. The lessons of the Trojan Horse, for example, do not support the idea that actualization of developmental potential unfolds automatically or without help. The elements of the intervention should include features such as long-term support systems, reconnection with fellow participants, follow-up (as opposed to one-shot deals), and ongoing activities begun during the program. Ideally, these features will be coordinated with those aspects of the organization and family-life holding environments that support development.

Safely taking risks in a leadership development program. We have discussed how leadership development must at some point threaten established ways of making meaning. Development can be seen as problematizing what was once taken for granted: “Probably … one should see the [developmental] sequence as one of coping with increasingly deeper problems rather than to see it as one of the successful negotiation of solutions” (Loevinger & Wessler, 1970, p. 7). Even when some new and more robust ways of making meaning are established by a person, feelings of loss can be profound: “It may be a great joy to discover a new and more complex way of thinking and seeing, but what do we do with all those hopes we had invested in those simpler terms (Perry, 1981)?” Those who run leadership development programs have a deep responsibility to address the risks involved, including maximizing the possibilities for beneficial outcomes, and obtaining informed consent from participants (Kaplan & Palus, 1994). Recognizing that programs differ greatly in focus and intensity, we consider the key points for maximizing the possibility for beneficial outcomes to be as follows:

Attention to readiness. The work in the program should be matched to the readiness of the participants. Participants should be assisted in self-selecting for the program based on an assessment of their own readiness for the work proposed. This means taking a “whole life” perspective on development—that is, being aware of possible influences of, and impacts on, personal, community, and family life as well as work life.

Equilibration. Attention must be given to appropriately stabilizing meaning structures, because much of the work of development involves disequilibrium—and extreme disequilibrium can be threatening, painful, and even harmful. The support capability of the participant’s organization should be assessed, and work should be done to insure that the program fits in well with the other developmental initiatives of the organization.

Follow-up. Participants must be helped with getting back to their lives after having been put off-balance. They must be helped in identifying their own resources. The program itself should provide ongoing developmental resources. Other initiatives by the sponsoring organization should be in place to continue the work of development.

We have described leadership development as the increasing capacity to make encompassing and adaptive meaning in a community. We can list a number of meaning-making processes that, according to this perspective, are potential leadership processes: problem solving, questioning and suspending assumptions, relating, influencing, valuing, engaging in dialogue, telling stories, planning/acting/reflecting, framing, and creating environments. These, however, cannot be viewed simply as skills to be learned. Neither can we expect these to pop out in finished form at the end of a leadership development program. How can we best conceptualize the nature of the outcomes we might hope for?

Our model specifies four categories of potential outcomes for a leadership development program: (1) competencies and taking action; (2) meaning structures; (3) the particular kind of superordinate meaning structures we call developmental stages; and (4) holding environments. As Figure 2 indicates, these are nested: One’s developmental stage frames other meaning structures, all of which frame competencies and action—all of which are supported (or not) by the holding environments. Each of these categories presents targets for development.

For example, taking action by going “against the grain” (or attempting to) can eventually lead to a change in developmental stage via the processes of experience, disequilibration, and potentiation. And vice versa: The equilibration of a new developmental stage makes it possible to take certain unaccustomed actions with a degree of integrity and competence (Drath, 1990).

Attention to each of these four categories is necessary in planning, implementing, following-up, and evaluating a leadership development program.

Competencies and taking action. The bottom line for any intervention is a significant increase in effective actions taken—for example, toward some goal or toward solving problems. The problem is that leadership requires facility with processes that cannot be treated as mere techniques, as if competencies were modular building blocks (Vaill, 1991). Truly effective empowerment, for example, is dependent on the long-term evolution in developmental stages and holding environments (Drath, 1990) and cannot normally be imparted as a competency (at least by the usual meanings of the word competent) during a leadership development program.

What can be done is to experiment with taking actions intending empowerment, see what happens, and then use the experiments to reveal and revise one’s assumptions, biases, perspectives, and so on (that is, revise one’s meaning structures). We call these reflective experiments with actions developmental experiments. Over the long term, developmental experiments may result in a new developmental stage and a step-change in the capacity to practice effective empowerment. During the course of such action-learning, we might reasonably hope that more—and more effective—action is taken.

Developmental programs in general are not expected to show broad, immediate transfer. What is expected to be carried back to the workplace is some facility for engaging the processes of development, including an experimental, reflective approach to taking action, and a better map of where these developmental experiments may lead.

Are there any competencies which a leadership development program might hope to impart by the end of a program? We believe that competencies having to do with engaging the processes of action-learning and development in one’s own world are achievable by the end of a multiple-contact leadership development program. “The idea is that it’s an experiment and you are the thing that is being experimented on and you are in charge of it” (R. M. Burnside, personal communication, October 18, 1994).

In general, these competencies include concepts and techniques for the enhancement of reflection, action planning, experimenting with new or improved actions in one’s world, self-diagnosis and understanding, involving others in learning processes, and diagnosing and understanding one’s holding environments. For example, LeaderLab participants learn how to keep journals as a tool for reflection; develop, test, and revise personal visions and action plans; and practice a holistic “head, heart, and feet” learning model. These learning competencies are pursued as tools in service of the long-term development of leadership capacities.

Thus, according to our model, if LeaderLab fails to immediately “transfer” the competencies it teaches (for instance, system thinking and maintaining flexibility) back to the workplace, it is not necessarily an indication that the program has not promoted development. In the words of one participant, “You can hear the song, but it may be that you’re unable to sing the words yet. It’s difficult.”

Meaning structures. Leadership development programs help people acquire new, revised, and alternative ideas, maps, insights, and perspectives. These will almost certainly not be integrated immediately into a whole new developmental stage—neither will they easily assimilate into one’s present stage of development (assuming the participant is matched with a program meant to challenge the person beyond his or her own present stage of making meaning). At first, these new meaning structures may be exercised as tools—with a longer-term potential of fostering a whole new way of looking at things (as discussed above with respect to the idea of potentiation and “the Trojan Horse”).

For example, Senge (1990) describes systems thinking (in our present terms) as a new meaning structure. Systems thinking can be trained for and can be evaluated as an outcome. An individual can be formally and rigorously assessed on how well he or she can utilize the meaning structure of systems thinking. Per our model, the meaning structure of systems thinking can serve as a framework for increased competency in analyzing a situation and taking action. Beyond its use as a tool, systems thinking can become the basis for a new developmental epistemology, what Basseches (1984) calls “the dialectical mode.”

Likewise, the meaning structure of total quality management (TQM) serves as a framework for taking action and can be fostered by the use of tools (such as fishbone diagrams). But it is important not to be obsessed by competency with tools as developmental outcomes. It is possible to acquire tools and still not “get it”—that is, still not be able to discern the underlying connections, values, and aims of total quality. It is quite possible that the Trojan Horse will be subjugated by the prior entrenched attitudes, rather than vice versa. Indeed, TQM often serves as a veneer over underlying traditional worldviews (Torbert, 1992).

Developmental stages. People undergoing a developmental experience at different points in transition will experience the program differently and have different outcomes (Lahey et al., 1985; Perry, 1981).

For a person in equilibrium within a stage, the outcome might be the temporary loss of balance associated with glimpsing the limits of that stage—with some potentiation for long-term movement in the same direction. Alternatively, if the program is set up such that it denies the participant’s epistemology, then the outcome for the person might only be an indignant feeling of having wasted time.

For a person who has already begun to encounter the limits of a stage, the outcome might be frustration and confusion—and potentiation brought on by a full confrontation of those limits. William Perry (1981) described a dualistic-stage student enrolled in his “Strategies of Reading” course who expected to have Knowledge ladled out by an Authority. This was not at all Perry’s style. Although the student improved immensely according to comparative scores on pre- and postcourse tests of reading speed and comprehension, he exhibited extreme frustration and apparent potentiation: “This has been the most sloppy, disorganized course I’ve ever taken. Of course I have made some improvement, but this has been due entirely to my own efforts” (p. 77, emphasis in original).8

For a person who has already begun to transcend a stage, the outcome might be the elation of discovering a new way to understand one’s self and the world. Also, the outcome might include a need to affirm the new structure by denying or rejecting the older structure and its trappings.

Finally, a person who had already begun to deny an older stage might achieve a kind of awakening, coming fully into the new stage, and assimilating (rather than denying) the older stage. A person who achieves such an awakening might be able to offer a whole new mode of being to their work and to their organization. On the other hand, if the organization does not have a holding environment sufficient to sustain that person in his or her new stage of development, that person might feel compelled to leave (Bushe & Gibbs, 1990).

There are a number of methods available for assessing stage and stage changes. Such changes typically take place over a span of years (depending on what one defines as a stage) and usually cannot be attributed to specific programs or events (Kegan, 1982; Perry, 1981; Torbert, 1987). Yet according to our model, stage assessment can be useful for understanding and facilitating the overall course of development in an individual—including readiness, process, and outcomes. Methods of stage assessment include:

(1) The Washington University Sentence Completion Test (WUSCT). The WUSCT was developed by Jane Loevinger (Loevinger & Wessler, 1970) as a measure of stage of ego development. A version of the instrument was used by Torbert (1987) and his colleagues in their research, with different labels for the stages.

(2) A number of assessment methods have been developed using the Perry scheme for the assessment of stages of intellectual development. The Center for the Study of Intellectual Development offers a full range of services facilitating use of the Perry scheme.9

(3) Formal assessment of the Kegan stages of meaning-making and transitional substages requires training in the Subject-Object Interview methodology (Lahey et al., 1985).

(4) Michael Commons has developed a method for assessing stages of cognitive development from interview transcriptions (Commons & Richards, 1982).

(5) Michael Basseches (1984) has developed a method of assessing the use and coordination of dialectical schemata (although not primarily from a stage perspective).

Holding environments. The ability of environments—not just individuals—to hold and develop certain forms of meaning is essential to leadership development. Communities of practice are holding environments for leadership. According to our own view, we have emphasized individual development in this paper, and have said fairly little about how such an evolution of community would look like. One reason for this is that we at the Center have historically focused on individual development; we have paid relatively less attention to the evolution of processes of leadership as embedded in communities. However, our recent work in understanding, for example, dialogue, learning groups, total quality systems, and leadership as processes are efforts to broaden our view.

See Appendix A for an example of how readiness for development, developmental processes, and outcomes play out with an individual in a leadership development program.