Although leadership development is widely acknowledged as important, our understanding of it is largely implicit. This has made programs that seek to promote it difficult to design and implement, and challenging to evaluate effectively.

In this paper we will present an explicit model of how leadership development can be promoted using programs. We are speaking here primarily to people who are responsible for leadership development in organizations or who design or evaluate programs. The model, however, should also be of interest to researchers who are studying leadership and to practicing leaders who are seeking to understand their own development.

Because the model we present here is the product of a distinct view of leadership and development, we should briefly describe our perspective (see Drath & Palus, 1994).

Historically, leadership has been understood in terms of dominance and influence: An individual called a leader acts in some way to change the behavior or attitudes of others called followers. We think that this notion of leadership can be seen within a larger context, one which includes more general social processes. In brief, we regard leadership as meaning-making in a community of practice: People engaged in a shared activity make sense of their experience together so that they can communicate, cooperate, and agree about what is happening, and so that they can interpret, anticipate, plan, and act. From this perspective it is possible to see the common underlying leadership processes in a range of situations from dictatorships to so-called leaderless work groups.

Also from this perspective, leadership development takes on a different look. It is usually seen as an almost exclusively individual process in which a leader gains additional skills to influence followers. If leadership is understood as a social activity, though, then leadership development must involve some change in the collective activity, in addition to some change in individuals.

More specifically, any meaning structure (or interpretation, construction) that a community uses to make sense of things will eventually come up against something that it cannot handle. The process of adaptation takes place as people try to collectively evolve a new meaning structure that can explain the changed conditions. It involves the development of the leadership process and can thus be included in the idea of leadership development (Heifetz, 1994).

The adaptive processes of leadership development can happen in three ways: when new forms of practice are created; when people are brought into new ways of relating to others in the community; and when individual members develop psychologically. Our model in this paper deals primarily with the last of these—individual psychological development—in light of the requirements of the first two.

Thus, our focus is on the use of programs to enhance the growth of the individual’s ability to participate in the leadership processes of the community of practice.

We are concentrating on that aspect here because we believe that individual development is a key component of leadership development. Also, the use of programs in support of individual leader development is common and widely valued, even if poorly understood.

Before we can say how individual psychological development (and, through it, leadership development) can be promoted in a program, we have to say more about individual development in general.

Just as communities create meaning structures to make sense of their experience, so do individuals. We take the position that, typically, for each of us there is one meaning structure that organizes and comprehends all the others. Jean Piaget (1954) referred to this metastructure as an “epistemology.” Throughout our lives we evolve a succession of such structures, which may therefore be thought of as stages of development (there are also smaller, partial, or more idiosyncratic shifts in meaning structure within the larger wholes). According to this view, there is a general pattern to development, such that everyone tends to go through the same stages in the same order.

A key concept of stage development is that each stage is qualitatively distinct but depends on—and, in fact, incorporates and transcends—the previous one.1 Later stages are built upon earlier ones: A person must sufficiently address the inherent tasks of earlier stages to ensure success in later stages (Erikson, 1963). The abilities of earlier stages may remain available, but in ways that are reorganized and coordinated by the later stage.

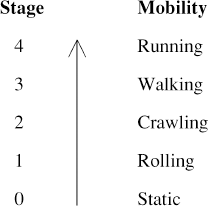

As a simple example of stages of development, consider the sequence involved in learning how to walk, illustrated in Figure 1.2 At first the infant is immobile. A step change occurs when it is able to repeatedly organize its movements in order to roll. This has a revolutionary effect: The infant’s experience of the world becomes fundamentally reorganized by its ability to roll around in it. Likewise, crawling is a reorganization of movement that has a profound effect on experience. And so on, with walking, then running.

Figure 1. A Stage Developmental Model of Learning to Walk

(adapted from Boydell, Leary, Megginson, & Pedler, 1991)

This view of development makes it possible to distinguish between development and something it is often confused or equated with: learning. When a single new insight or piece of information is assimilated into the underlying frameworks of one’s current stage, this can be understood as learning. Sometimes, however, the stage cannot adequately assimilate new information, and a new stage that is more encompassing is generated to better organize complex and diverse information. This process of accommodation—more specifically, reorganization of one’s epistemology—is the essential motion of development (Piaget, 1954).3

It also allows us to draw a distinction between training programs and development programs. A training program attempts to impart skills within a person’s existing stage of development. A program that teaches a person to type is a simple example of a training program. A development program, in comparison, helps a person stretch toward a qualitatively new set of meaning structures, toward a new stage (Boydell, Leary, Megginson, & Pedler, 1991).

A development program may also help a person acquire skills but in ways that challenge his or her overall ways of making meaning. Thus “going to college” is an example of a development program (Perry, 1970): Individual classes may involve only learning or training, but the entire course of study (if successful) imparts a comprehensive new meaning structure. Of course, the distinction between training programs and development programs is rarely clear-cut, because training and development interpenetrate: Rigorous training tends to stretch a person’s frameworks, and development requires the learning of new skills.