Chapter 3 The Ten Steps Process

I have been impressed with the urgency of doing.

Knowledge is not enough; we must apply.

Being willing is not enough; we must do.

– Leonardo da Vinci

In This Chapter

Step 1—Define Business Need and Approach

Step 2—Analyze Information Environment

Step 6—Develop Improvement Plans

Step 7—Prevent Future Data Errors

Step 8—Correct Current Data Errors

Step 10—Communicate Actions and Results

Introduction

Remember the map example at the beginning of Chapter 2? Maps come in different levels of detail and you will use those different levels depending on your needs at a particular moment. Suppose you are driving across the country. You might start with a high-level map of the country in which you are traveling (we will use the United States for our example here). You get an idea of the layout of the country, the number of states you will travel through, and the location of the cities in the various states, and you outline a plan to drive from your current location to your final destination.

Alternatively, you may decide that with the amount of time you have for the trip driving is not the best way to get to your location, so you book an airplane flight for the first leg of the journey. Once you arrive at your destination city, the U.S. and state maps do not help you get from the airport to your hotel. A different level of detail is needed, so you look at a street-level map.

All along the way, there are a number of approaches to get to your goal. You could plan the complete trip yourself, using maps and travel books to provide necessary information. You could ask friends and family who have taken similar trips in the past for suggestions. Or you could use a travel agent to plan the complete trip or just book the transportation. Once you reach your city, you could hire a tour guide for a specific activity. You might use GPS or an online map tool to provide step-by-step driving instructions.

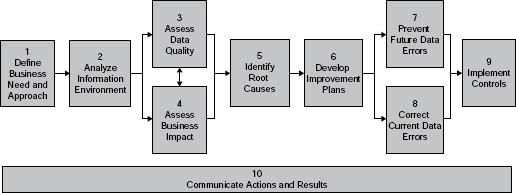

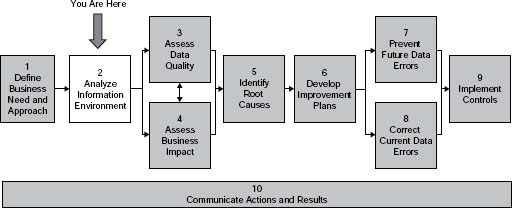

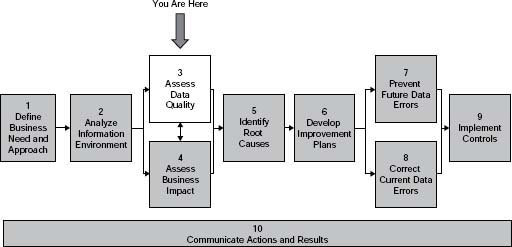

Think of The Ten Steps as your map (Figure 3.1). Apply them to meet your needs—with different combinations of steps and high-level or detailed instructions depending on your requirements at the time. The instructions, techniques, examples, and templates in the steps are meant to provide enough direction so you can understand your options. It is up to you to decide what is relevant and appropriate to your situation.

Figure 3.1 • The Ten Steps process.

Source: Copyright © 2005–2008 Danette McGilvray, Granite Falls Consulting, Inc.

The Ten Steps Conventions

As you know The Ten Steps process was introduced in Chapter 2. This chapter provides detailed instructions and examples for each of those steps. The Ten Steps conventions are described here:

You Are Here Graph—Each step (1–10) is introduced by the graph of The Ten Step process and an indication of where you are in it.

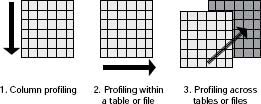

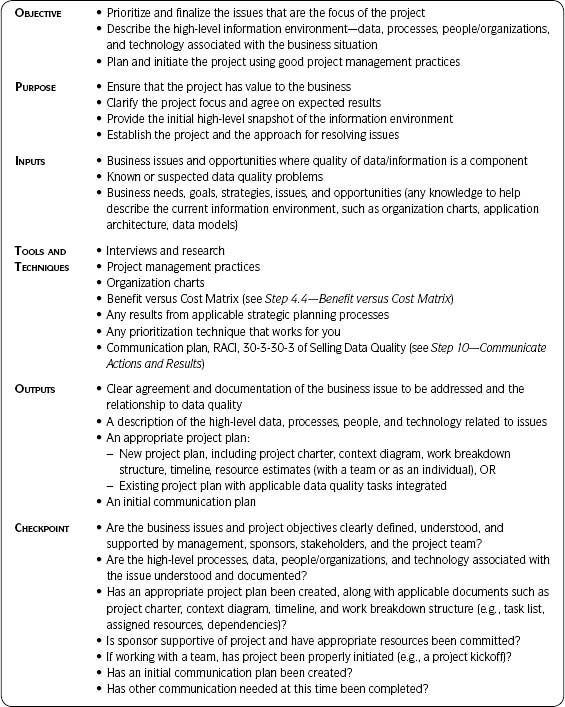

Step Summary Table—This table describes (for that step) the objective, purpose, inputs, tools and techniques, outputs, and checkpoint. See Table 3.1 for further detail.

Business Benefit and Context—This section contains background helpful for understanding the step and benefits from completing the step.

Approach—This section contains the step-by-step instructions for completing the step.

Sample Output and Templates—This section contains examples of forms and tables that projects can use to structure their own outputs.

Note that the first five steps of The Ten Steps also contain substeps and a further detailed process flow. The substeps are also presented according to the format of Business Benefit and Context, Approach, and Sample Output and Templates.

The Step Summary Table

The steps’ summary in Table 3.1 provides a quick reference to the main objectives, inputs, outputs, and checkpoints for each of the Ten Steps.

Table 3.1 • Step Summary Table Explained

Step 1 Define Business Need and Approach

Introduction

The importance of this step cannot be overstated. Business goals and strategies should drive all actions and decisions. Information-related projects should always start with the question, “Why is this important to the business?” Anything done with information should support the business in meeting its goals, and this step ensures that you are working on situations of importance to the business.

You may be focusing on issues (situations that are suboptimal) or opportunities (something new to be used to your advantage). This step shows how to implement the first section in the Framework for Information Quality—Business Goals/Strategy/Issues/Opportunities. (See the Framework for Information Quality section in Chapter 2.)

Businesses embarking on information and data quality improvement projects are often already aware of the issues affecting them most urgently. Step 1.1—Prioritize the Business Issue builds on that awareness and prioritizes the business issues or opportunities where data quality is suspected to be a major component. This is also where the information environment is described at a high level. The information environment comprises the data, processes, people/organizations, and technology associated with the issues to be addressed. Step 1.2—Plan the Project initiates the project to deal with the issues chosen.

Whether you are embarking on a data quality project with a team, focusing as an individual contributor on one data quality issue for which you are responsible, or integrating data quality activities into another project or methodology, this step is critical. Many a project has failed because of misunderstanding between those involved (sponsors, management, teams, business, IT, etc.). Don’t let lack of clarity regarding what will be accomplished and why keep your project from succeeding.

Effective planning is essential to the successful execution of any project, and defining the business need and approach provides the necessary focus for your project activities (see Table 3.2). I’m a big believer in taking enough planning time to ensure that you are looking at those issues or opportunities worth investing in and in good project management planning.

Kimberly Wiefling, in Scrappy Project Management™: The 12 Predictable and Avoidable Pitfalls Every Project Faces, puts it well when she says, “Just enough planning to optimize results. Not a drop more! … But not a drop less either.”

Table 3.2 • Step Summary Table Explained

Step 1.1 Prioritize the Business Issue

Business Benefit and Context

Your project should only spend time on those issues where you expect to get results worth the time and money spent. In many cases there will be several issues or opportunities from which you will have to choose. You need to prioritize where to focus your efforts. There are multiple ways to prioritize issues, and this step mentions just one. If you have a favorite technique for prioritization, use it here. If you are already very clear about the business issues or opportunities to address, you only need to document and confirm agreement on the data quality issues your project will address before devising your project plan.

Who should be involved in this step? A draft list of the issues should be created by the responsible management and project manager. (Remember, if you are working on a data quality issue yourself you are the project manager and the project team in one.) Ensure that appropriate stakeholders are engaged.

A stakeholder is a person or group with a direct interest, involvement, or investment in the information quality work. Stakeholders are those “actively involved in the project or those whose interests may be positively or negatively affected by execution or completion of the project and its deliverables.”1 For example, the person responsible for manufacturing processes would be a stakeholder for any data quality improvements that impact the supply chain. Stakeholders may also exert influence over the project and its deliverables. Examples of stakeholders include customers, project sponsors, the public, or organizations whose personnel are most directly involved in doing the work of the project.

The list of stakeholders may be long or short depending on the expected scope of the project. The point is that stakeholders must agree on the business issue that will be addressed by the data quality project.

Approach

1. List the specific issues or problems.

Focus on those data quality issues deemed critical—based on what you know at this time.

Consider issues or opportunities in the following areas:

Lost revenue and missed opportunities—where revenue could increase if the data quality issue were addressed—for example, increasing the products or services purchased because the customer information was correct and therefore more customers were able to be contacted. Put another way, the customer did not get the chance or choice of doing business with your company because they were never contacted as a result of incorrect address, phone, or email data.

Lost business—where your company once had a customer or vendor, but they chose not to do business with you because of some type of problem where data quality was a contributing factor. For example, the inability to ship products correctly may influence the customer to work with another company. The inability to pay invoices in a timely manner may influence the vendor to refuse to provide parts, materials, or supplies to your company.

Unnecessary or excessive costs—where the company incurs costs due to wasted time and materials from rework, data correction, cost to recover lost business, impact to processes, and so forth. For example, manufacturing stops because materials were not ordered and available in a timely fashion due to incorrect inventory data.

Catastrophe—where poor data quality contributed to disastrous results such as legal repercussions, loss of property, or loss of life.

Increased risk—where data quality issues increase risk to your company. Examples are compliance and security failures due to poor-quality data or exposure to credit risks when purchases by one customer are associated with duplicate customer master records, causing the credit limit for that customer to be exceeded.

Shared processes and shared data—where several business processes share the same information, and quality problems in the data impact all of them; or one key business process central to the organization is affected by the lack of good data quality. For example, supplier (or vendor) master records impact the ability to quickly place an order with your supplier and also impact the timely payment of that supplier’s invoices. If your company only interfaces with its customer via the website, then the quality of information presented on the website is of critical importance.

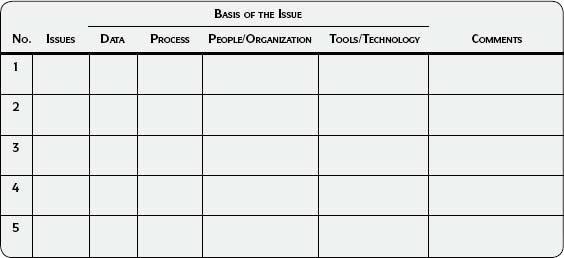

2. Indicate the basis of each issue.

Based on what you know now, indicate if the basis of each issue is data, processes, people/organizations, and/or technology. Brainstorm and capture your ideas about importance and precedence. Use the Issue Capture Worksheet (Template 3.1) in the Sample Output and Templates section at the end of this step.

3. Discuss and prioritize the issues.

Choose the issues in which you suspect data quality to be a large component and contributing factor. Use your favorite technique for prioritizing, or you may want to use Step 4.4—Benefit versus Cost Matrix to determine which issue should be the focus of your project. Invite data and process stakeholders to contribute their concerns and perspectives.

4. Identify the associated data, processes, people/organizations, and technology associated with the issue(s) chosen.

Answer the following questions:

- Which business processes are impacted?

- Who are the people or organizations involved?

- Which data subject areas are impacted?

- Where do the data reside (i.e., applications, systems, databases involved)?

- Are there other tools associated with the issue?

Sample Output and Templates

There are many ways to capture and prioritize issues. The Issue Capture Worksheet (Template 3.1) is one simple example of capturing and categorizing business issues at this early stage of the project.

Template 3.1 • Issue Capture Worksheet

Step 1.2 Plan the Project

Business Benefit and Context

Using good project management techniques is essential to the success of any project. The intent of this step is not to teach project management in detail, but to show how to use project management skills as they relate to data quality. If you are new to project management, there are many books, articles, conferences, and websites devoted to this topic. Effective planning is essential to the successful execution of an information improvement project, and defining the business need and approach will provide the necessary focus for the improvement activities.

Approach

1. Identify the steps from The Ten Steps process needed to meet the business need.

Does the sponsor need a high-level assessment to seek further funding/support? Study your environment and business context. Are there specific items that need to be assessed?

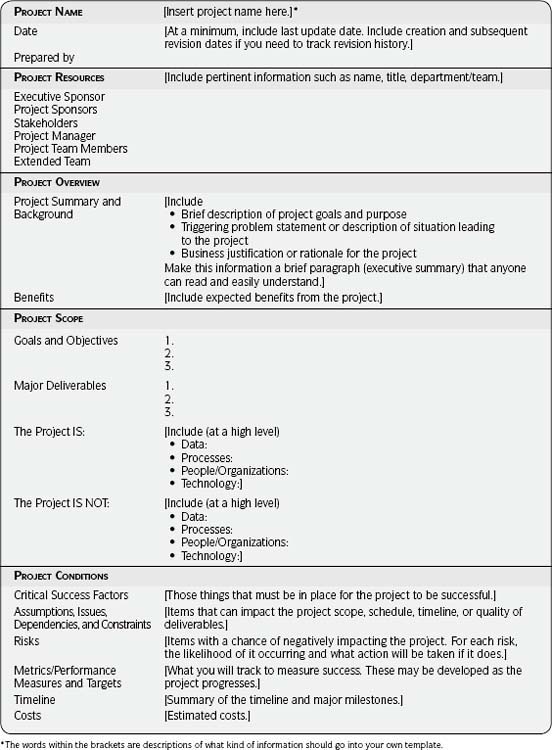

2. Create a project charter.

Create a project charter that is “right-sized” for your project. See the Project Charter template (Template 3.2) in the Sample Output and Templates section of this step.

3. Create a high-level context diagram.

Visually describe the high-level data, processes, people/organizations, and technology involved. A picture is really worth a thousand words at this point. A good context diagram is very useful for communicating the scope of the project.

4. Develop a project plan and timeline.

Use The Ten Steps process to plan your project and work breakdown structure. Choose the appropriate steps and techniques for your individual work or for a data quality project. Choose the appropriate steps and techniques if incorporating into another methodology or project, and ensure that the activities are integrated into it.

5. Use other good project management practices.

For example, create a template and process for tracking action items and issues. See the Tracking Issues/Action Items template (Template 3.3) in the Sample Output and Templates section of this step.

6. Create your initial communication plan.

See Step 10—Communicate Actions and Results.

7. Document all information gathered in Step 1—Define Business Need and Approach.

8. Confirm and ensure

- Management support

- Approval for the project

- Resources committed to the project

9. Kickoff!

Sample Output and Templates

Project Charter

If your company does not have a required template for project charters, use Template 3.2 as a starting point. Discard those sections that do not apply and add sections relevant to your situation. Try to keep the charter to one to two pages. You may need a more detailed project charter than the one shown in Template 3.2. If you do, maintain a one-to two-page summary version and update it throughout the project to provide an at-a-glance view that anyone involved with the project should see. Refer to the summary for content when summarizing your project in various communications. Even if you are an individual, spend 30–60 minutes considering these categories for yourself—it will provide a basis for discussion with your manager to ensure that you are both in agreement as to your activities and goals.

Template 3.2 • Project Charter

Template 3.3 • Tracking Issues/Action Items

Action Items

Use your preferred method for tracking action items throughout the project. The Tracking Issues/Action Items template (Template 3.3) shows one option. This template also works well in a spreadsheet format. Keep one sheet for open action items. As the items are closed, move to a different sheet. That way you can easily see all open items and all closed items in their respective sheets.

Step 1 Summary

Determining your business need and approach sets the foundation for all future data quality activities. All projects require some level of prioritization and planning—whether as a focused data quality project, as an individual contributor implementing ideas yourself to support your own job responsibilities, or if integrating data quality into another project or methodology.

Completing this step at the right level of detail and focusing on what is relevant and appropriate are critical. If you ignore this step or do it poorly, you have already guaranteed failure, no more than partial success, or lots of time and effort focusing on the wrong thing. But if you do it well, you have a springboard for a successful project and the real opportunity to bring value to your organization.

![]() Communicate

Communicate

Here are a few ideas for communicating at this point in the project:

![]() If working with a project team, communicate with and get support from IT and business management, sponsors, stakeholders, and team members.

If working with a project team, communicate with and get support from IT and business management, sponsors, stakeholders, and team members.

![]() If integrating data quality activities into another project or methodology, communicate closely with the project manager and ensure that the tasks are integrated into the project plan and known by team members.

If integrating data quality activities into another project or methodology, communicate closely with the project manager and ensure that the tasks are integrated into the project plan and known by team members.

![]() If working on a specific data quality issue yourself, clarify with your manager that you both agree on the focus of your project.

If working on a specific data quality issue yourself, clarify with your manager that you both agree on the focus of your project.

![]() Use your one- to two-page project charter as input to your communications.

Use your one- to two-page project charter as input to your communications.

![]() Create a draft of your communication plan.

Create a draft of your communication plan.

![]() Checkpoint

Checkpoint

Step 1—Define Business Need and Approach

How can I tell whether I’m ready to move to the next step? Following are guidelines to determine completeness of the step:

![]() Are the business issues and project objectives clearly defined, understood, and supported by management, sponsors, stakeholders, and the project team?

Are the business issues and project objectives clearly defined, understood, and supported by management, sponsors, stakeholders, and the project team?

![]() Are the high-level processes, data, people/organizations, and technology associated with the issue understood and documented?

Are the high-level processes, data, people/organizations, and technology associated with the issue understood and documented?

![]() Has an appropriate project plan been created, along with applicable documents such as a project charter, context diagram, timeline, and work breakdown structure (i.e., task list, assigned resources, dependencies)?

Has an appropriate project plan been created, along with applicable documents such as a project charter, context diagram, timeline, and work breakdown structure (i.e., task list, assigned resources, dependencies)?

![]() Is the sponsor supportive of the project and have the appropriate resources been committed?

Is the sponsor supportive of the project and have the appropriate resources been committed?

![]() If working with a project team, has the project been properly initiated (e.g., a project kickoff)?

If working with a project team, has the project been properly initiated (e.g., a project kickoff)?

![]() Has an initial communication plan been created?

Has an initial communication plan been created?

![]() Has other communication needed at this time been completed?

Has other communication needed at this time been completed?

Step 2 Analyze Information Environment

Introduction

This is the step at which you first put on your investigator hat (see figure above and Table 3.3 on page 78). Whether you relate to Sherlock Holmes or CSI (Crime Scene Investigation), the common theme is using techniques to solve a mystery. Solving the “Case of Poor Data Quality” requires interpreting clues that can only be uncovered by investigating the information environment.

Read Chapter 2 before starting this step. The concepts combined with the process (Steps 2.1–2.7) will help you understand what can often be a complex environment. When you understand the environment you will do better analysis and make better decisions on where to focus as you continue throughout your project.

The natural inclination is to skip this step and jump right into data quality assessment. However, completing Step 2—Analyze Information Environment ensures that the data extracted and assessed are the data associated with the business issue. Otherwise, it is not unusual to find that data have to be extracted multiple times before getting the data you really need. Analyzing the information environment will usually be more in-depth for a data quality assessment than for a business impact assessment.

![]() Key Concept

Key Concept

Step 2—Analyze Information Environment provides a foundation of understanding that will be used throughout the project:

- Ensures that you are assessing the relevant data associated with the business issue.

- Provides an understanding of requirements—the specifications against which data quality is compared.

- Provides a context for understanding the results of the data assessments and helps in root causes analysis. The more you understand the context and the environment that affect the data, the better you will understand what you see when you assess the data.

- Provides an understanding of the processes, people/organizations, and technology that affect the quality and/or value of the data.

- Allows you to develop a realistic data capture and assessment plan.

For business impact assessments, focus on the Apply phase of the Information Life Cycle POSMAD. Spend enough time on this step to link the business issues so there is confidence that a detailed impact assessment will focus in the right areas.

No matter what type of assessment is next in your project, everything learned in this step will help you interpret your results after completing your assessments, find root causes, and identify people with the knowledge that should be included in the project.

![]() Warning

Warning

If you are going to assess data quality in any depth, avoid wasting time and money by resisting the temptation to immediately start extracting and analyzing data. Immediately extracting without understanding the information environment often results in multiple extracts and rework before you get to the actual data relevant to the business issue.

Spend just enough time in Step 2 to understand your information environment so you can ensure that the data being assessed for data quality and the information being assessed for business impact are actually related to the business issue to be resolved.

There are seven substeps within Step 2. The flow of this step is shown in Figure 3.2 on page 80. Use Step 2—Analyze Information Environment to

- Understand relevant requirements—Not understanding requirements is often a factor in data quality problems.

- Understand relevant data, processes, people/organizations, and technology—the four key components in the Framework for Information Quality.

- Document the Information Life Cycle—in which you combine the data, processes, people/organizations, and technology to define and understand the life cycle through the POSMAD phases.

- Develop a realistic data capture and assessment plan—based on your background investigation.

IMPORTANT!!! Each of the substeps in Step 2 are interrelated. Start with the area in which you have the most information or with which you are most familiar (requirements, data, process, people/organizations, or technology) and work out from there in any order until you have obtained the relevant information at the appropriate level of detail. Define the Information Life Cycle and Design Data Capture and Assessment Plan will most likely be the last steps, as they require understanding from the previous steps.

You will make many choices along the way about what is relevant to the business issues. Table 3.4 (see page 80) discusses three extremely important questions you need to consider throughout the life of your project: What is relevant? What is appropriate? What is the right level of detail? The answers to these questions will impact where you focus your efforts, how much time is spent, and the nature of your results. Make rapid decisions based on what you know at the time and move on. If circumstances change or new knowledge comes to light, you can make adjustments from there.

Table 3.3 • Step 2—Analyze Information Environment

Table 3.4 • Learning to Scope

What is relevant? What is appropriate? What is the right level of detail?

Determining what is relevant, what is appropriate, and what is the right level of detail needed to meet your objectives is important throughout The Ten Steps process. Using good judgment regarding these three ideas starts in Step 2—Analyze the Information Environment. Use the following information to help:

Relevant—in this context means that what you are looking at is associated with the business issue to be resolved. Focus on that issue.

Human Element—As you explore the business issue, you may find that the problem is broader than you imagined. This can feel overwhelming. Thinking about what is relevant helps you to narrow your focus to the business issue at hand.

Manageable—If the scope is too broad, can you focus on specific parts of an issue and build upon results?

Appropriate—Choosing the applicable steps from The Ten Steps process and understanding the key components and other factors affecting information quality and the Information Life Cycle at the suitable level of detail.

Level of Detail—The level of detail required for each step will vary depending on the business needs and your project scope. Start at a high level and work to lower levels of detail only if useful.

Questions to Ask:

- Will the detail have a significant and demonstrable bearing on the business issue?

- Will the detail provide evidence to prove or disprove a hypothesis about the quality of the data?

Use your best judgment and move on:

As you proceed throughout the step and the rest of the methodology, if you find that more information is needed, gather more detail at that time. You will be most successful if you implement this step as an iterative process.

You will uncover many items of interest. On one project team we gave each other permission at any time to ask, “Are we going down a rat hole?” This was the signal to stop and ask ourselves if the level of detail or item of interest was relevant to the business issue. If yes, we agreed to spend more time. If no, we refocused our efforts on the activities and analysis that kept our eyes on the business issue. This method helped us stay on track and use our time well.

Spend enough time to get the foundational information needed to proceed effectively. Don’t skip this step, but don’t get too far into detail that may be unnecessary. You can always come back later and get additional detail if needed.

Step 2.1 Understand Relevant Requirements

Business Benefit and Context

Requirements indicate those things necessary for the business to succeed, such as processes, security, or technology. Some requirements may be external—those with which the business is obligated to comply, such as privacy, legal, governmental, regulatory, and industry. Because the data should support compliance with all these requirements, it is important to understand them as soon as possible in the project.

![]() Key Concept

Key Concept

As Olson notes in Data Profiling: The Accuracy Dimension: “You cannot tell if something is wrong unless you can define what being right is.”

– Jack E. Olson

Approach

1. Gather requirements.

Ensure that the requirements are relevant to the business issues, associated data, and data specifications necessary for compliance with them. Consider requirements in the following areas: business, technology, legal, contractual, industry, internal policies, privacy, security, compliance, and regulatory. You may need to contact your company’s finance, legal, or other departments for help.

Use the Requirements Gathering template (Template 3.4) as a starting point to capture requirements and pertinent information.

Following is a sampling of regulatory and legal requirements that impact data or require high levels of data quality in order to achieve compliance2:

- The National Data Privacy Law

- Federal credit laws

- Federal privacy and information security laws (e.g., HIPAA)

- State laws

- Data laws affecting the Indian Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) industry

- The California Security Breach Notification Law

- The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002

- The Data Quality Act

- The U.S.A. Patriot Act

- The Corporate Information Security Accountability Act of 2003

2. Identify constraints.

Identify any constraints such as security, permissions, or access to data that may impact your project.

3. Analyze the requirements gathered.

Look at the various requirements for the same information, for the same organizations, and so on. These requirements will eventually need to turn into detailed data specifications to ensure that the data support adherence to them.

You will eventually need to detail how to comply with requirements from a data quality point of view. This can take place in Step 2.2—Understand Relevant Data and Specifications or in Step 3—Assess Data Quality. Also see the section Projects and The Ten Steps in Chapter 4 for suggestions on including data quality requirements gathering as part of the project life cycle.

4. Document results.

In your project documentation, list the requirements and constraints that will affect your project, and make action items to address them. Start tracking analysis results. See the Analyze and Document Results section in Chapter 5 for a template to help you track results.

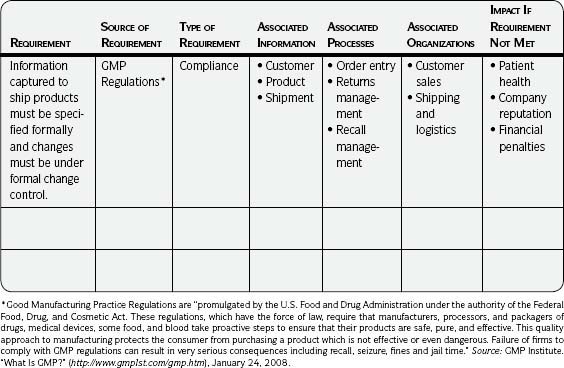

Sample Output and Templates

Following are explanations of the information to insert into the Requirements Gathering template (Template 3.4):

Requirement—Title and brief description.

Source of Requirement—The person who provided the information along with the specific source such as a particular law or internal policy.

Type of Requirement—Business, technology, legal, contractual, industry, internal policies, privacy, security, compliance, or regulatory. (Other categories may apply to your situation; discuss a meaningful way to categorize them.)

Associated Information—Information that must be in place in order to comply with the requirement OR the information itself that must comply with the requirement (if the requirement specifies the information).

Associated Processes—Processes in place when the information is collected or used. (You may decide to expand to processes that impact the information throughout the POSMAD life cycle at some point.)

Associated Organizations—Organizations, teams, departments, and the like, impacted by the requirement.

Impact If Requirement Not Met—The result if the requirement is not met: legal action, risk of fines, and the like. (Be as specific as possible with what is known at this time. This will drive decisions if trade-offs need to be made based on resources and time, or if there are conflicting requirements.)

Template 3.4 • Requirements Gathering

Step 2.2 Understand Relevant Data and Specifications

Business Benefit and Context

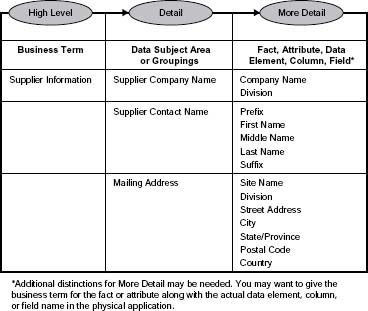

In this step you will identify in detail the data and the related data specifications relevant to the business issue. (See the Data Specifications section in Chapter 2 for more information.) The step will help you ensure that the data you assess for quality or business impact are the same information the business is concerned with. Data and information can be described at a high level by common business terms or by data subject areas or groupings. These subject areas or groupings can be further broken down to the detail of field names.3

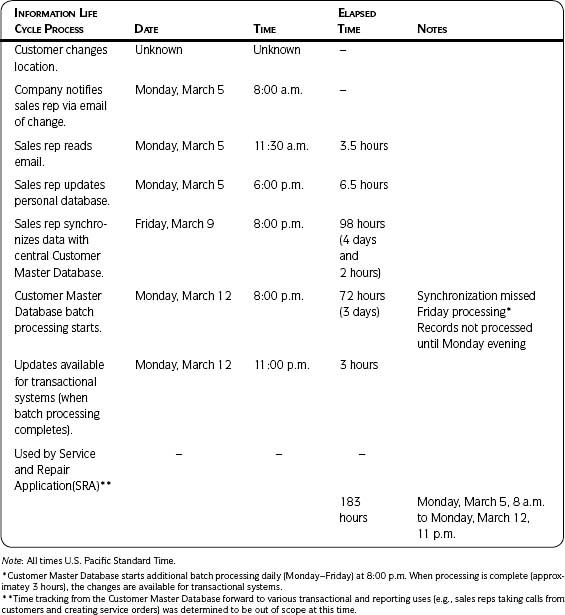

Figure 3.3 illustrates different levels of data detail. The business terms are usually related to how the business sees and thinks about the information. The most detailed are the actual tables and fields where the data are stored. In between are the data subject areas or groupings. It is critical that the information terms used by the business are linked to the actual data to be assessed.

![]() Best Practice

Best Practice

Use Information Already Available: You may expect that 80 percent of what is asked for in Step 2—Analyze Information Environment already exists. The value of this step is in bringing together existing knowledge in such a way that you can understand it better now than you did before.

You may start with the business terms or data subject areas relevant to the business issue. Then move to the detail of where the data are stored. Conversely, if you are more familiar with the fields where the data are stored, start with those terms. Trace fields in the database back to the business terms if you start with the database elements. This step is closely related to Step 2.3—Understand Relevant Technology; you may want to complete these two steps in parallel.

Approach

1. Identify the business terms and data subject areas or groupings relevant to the business issue and associated requirements.

- Capture the language used by the business through interviews, evaluation of documents, and examination of current system screens.

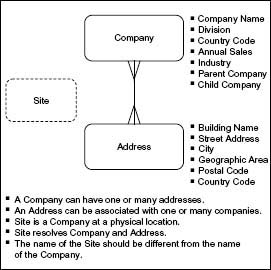

- Understand and document the data model, entities, and relationships, with a focus on what is relevant to the business issue and at the appropriate level of detail. A good data modeler is a valuable resource. Find one, get him or her on your project, and make use of his or her expertise!

The data model should be captured at one or both of the first two levels of abstraction as described in Table 2.5 in Chapter 2. Figure 3.4 shows an example of a context model that is useful for providing an overview of the scope of your assessment. In addition, a detailed conceptual model can be useful to show system scope, processes that can and cannot be supported because data do or do not exist, and related business rules. At a minimum, you need to know relationships at a very high level. This is yet another case when you will have to use your judgment as to the level of detail needed at this time. If there is no data model, developing one should be one of the first items on your recommendations list.

2. Identify the systems/applications/databases where the data are used and the corresponding databases where the data are stored.

This activity is closely related to Step 2.3—Understand Relevant Technology.

3. Correlate the business terms or data subject areas with the specific fields that store the data in the database.

See the example in Figure 3.3. The business terms will most likely be associated with how the information is applied; the more detailed terms, with where the data are stored. This is a key activity to ensure that the data you will be assessing are actually the data the business cares about.

4. Create a detailed data list for the data of interest.

See the Detailed Data List template (Template 3.5) in the Sample Output and Templates section of this step. Include all data that you may assess. Even if you actually assess only a subset of the data, it is easier to collect them all at this time. If you already have this information documented in another format, use that. Remember, the goal is to have a clear understanding of the data you plan to assess—not to put it in the exact format shown as an example.

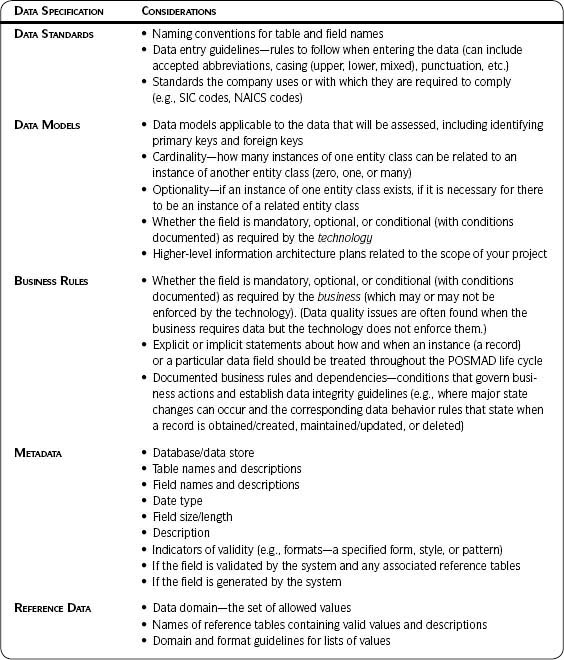

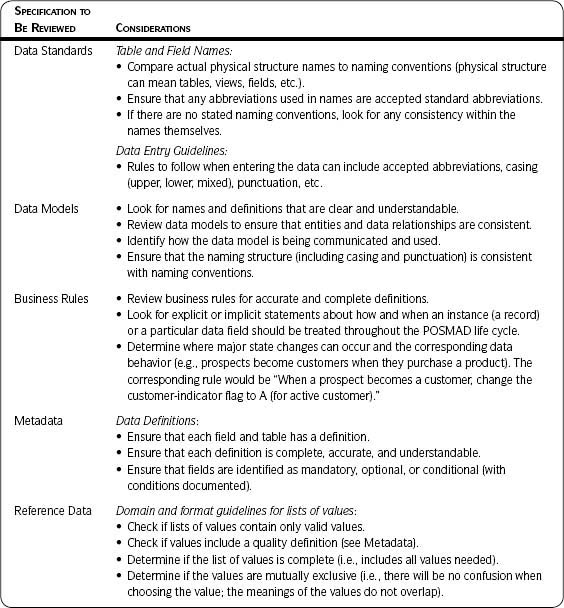

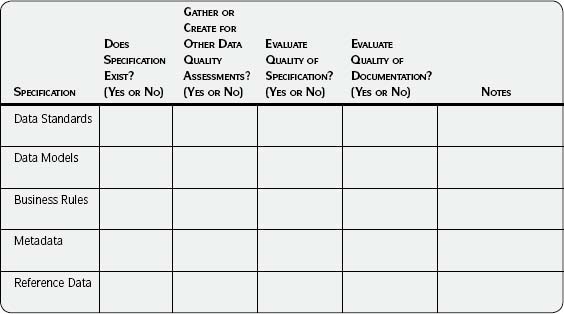

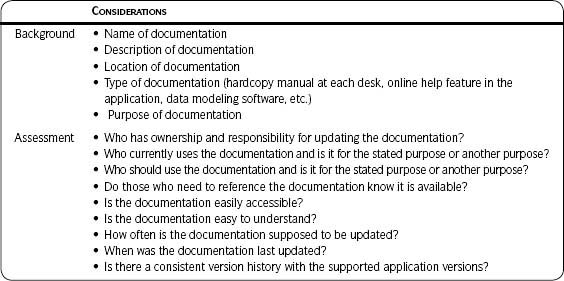

5. Collect relevant data specifications for each of the fields of interest.

See the section Data Specifications in Chapter 2 for more detail. Describe the data standards, data models, business rules, metadata and reference data, and other pertinent information known at this time. See Table 3.5 in the Sample Output and Templates section for examples.

Data specifications can be obtained from the following:

- Relevant requirements gathered in Step 2.1—Understand Relevant Requirements. (You may need to create specifications, such as detailed business rules and associated data quality checks, to support those requirements.)

- People knowledgeable about the data: business analysts, data analysts, data modelers, developers, database administrators (DBAs), and the like. Remember subject matter experts and knowledge workers applying the information in the course of their work, especially for business rules.

- Descriptions of the data available in existing data dictionaries, metadata repositories, or other documentation forms

- A relational database directory or catalog for data in a relational system for metadata on the column-level layout of the data

- Other sources that give you the layout that best represents the data according to the most likely extraction method

- A COBOL copybook or a PL/1 INCLUDE file that lays out the data if accessing an IMS or VSAM data source

- Interface definitions to application programs that feed data to the data source

- Structural information within the database management system (For example, in relational systems you can extract primary key, foreign key, and other referential constraint information.)

- Any TRIGGER or STORED PROCEDURE logic embedded within the relational system to find data-filtering and validation rules being enforced

- The program specification block (PSB) in IMS, which gives insight into the hierarchical structure being enforced by IMS

6. Understand and document the relevant data model, entities, and relationships.

Understand the data model, focusing on what is relevant to the business issue at the appropriate level of detail. Use and understand a detailed data model if available. As suggested previously, make a good data modeler a member of your project team.

The data model can show the system’s scope, processes that can and cannot be supported because data do or do not exist, and business rules supported by it. You may need to simplify a detailed model when speaking with those in the business. At a minimum, you need to know data relationships at a very high level.

7. If more than one data store is being assessed and compared, create a detailed data list for each one.

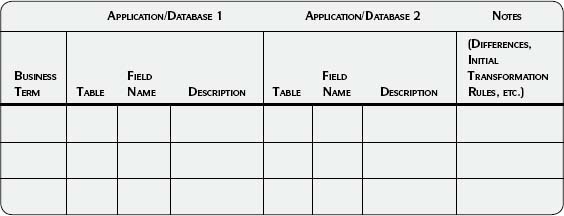

Once you have a detailed data list for each of the data stores, map the fields in each data store to the corresponding fields in the others. See the Data Mapping template (Template 3.6, page 89) in the Sample Output and Templates section of this step.

![]() Best Practice

Best Practice

Source-to-Target Mappings: You may be including source-to-target mapping activities in another project (such as a data migration). If so, document what you know about the mappings at this point. You will increase their quality and the speed at which they can be completed if you profile your data. See Step 3.2—Data Integrity Fundamentals for techniques to help you assess data for the purpose of mapping. You will confirm or change anything that you suspect about the mappings after you have completed your profiling.

8. Document additional information needed for the assessment.

See the Capture Data section in Chapter 5 for more information. Include what you know at this point for each of the data populations:

- Population to be assessed and associated selection criteria

- Output format needed for the assessment

- Anything you know about the sampling method

- Timing for extracts

- Anything else applicable and known now

All of these will be refined as needed in Step 2.7—Design Data Capture and Assessment Plan and finalized just before the data are extracted for the various quality and value assessments in Step 3 and Step 4.

9. Document any potential effects on data quality or business impacts recognized at this time.

For example, do you anticipate any problems with permissions and access to the data you want to assess?

If you haven’t already started systematically tracking results, do so now. See the Analyze and Document Results section in Chapter 5 for a template to help you do this. Remember, anything learned in Step 2 is valuable input to your data quality or business impact assessments.

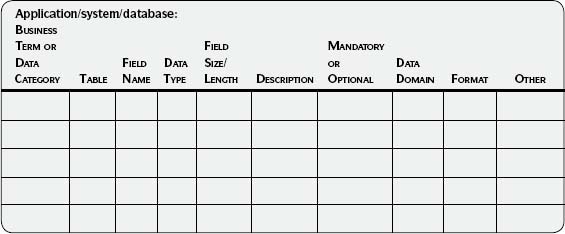

Sample Output and Templates

Use the Detailed Data List template (Template 3.5), to document the data of interest. Use the suggestions in Table 3.5 when collecting relevant data specifications for the data to be assessed.

Template 3.5 • Detailed Data List

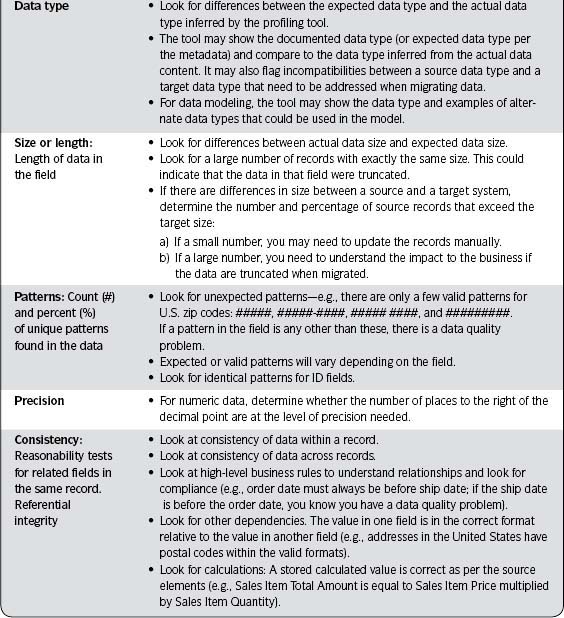

Table 3.5 • Collecting Data Specifications

Template 3.6 • Data Mapping

Use the Data Mapping template (Template 3.6) as a starting point if you will be assessing data in more than one application or database or if you are creating source-to-target mappings as part of another project.

Step 2.3 Understand Relevant Technology

Business Benefit and Context

Much of the information about technology will be discovered in the course of understanding the relevant data and specifications. This step is included to ensure that other technology is considered besides the obvious technology of the database where the data are stored. You may want to consider technology involved throughout the POSMAD life cycle—for example, any networks or messaging technology involved with sharing the data.

![]() Definition

Definition

Technology can be both high tech, such as databases, and low tech, such as paper copies. Examples are forms, applications, databases, files, programs, code, or media that store, share, or manipulate the data, are involved with the processes, or are used by people and organizations.

There are different levels of detail for technology (see Figure 3.5). If preparing for a data quality assessment, understanding technology related to the data at a table and field level will usually be required. If preparing for a business impact assessment, knowing an application and database may provide enough information to proceed.

This step is closely related to Step 2.2—Understand Relevant Data and Specifications. You may want to complete both steps in parallel.

Approach

1. Understand and document the technical environment.

Understand the applications and associated data stores. A data store is a repository for data, such as a relational database, an XML document, a file, or file repository, or a hierarchical database (LDAP, IMS).

For each type of technology understand the name of the software (the common name used by the business and the “legal name” used by the vendor if a third-party package), the version in use, the teams responsible for supporting the technology, the platform, and so forth.

You may need to understand the technology associated with sharing the data, such as networks or an enterprise service bus. Look at supporting technology throughout the POSMAD life cycle.

2. Make use of already-existing documentation and knowledge from Information Technology (IT) resources.

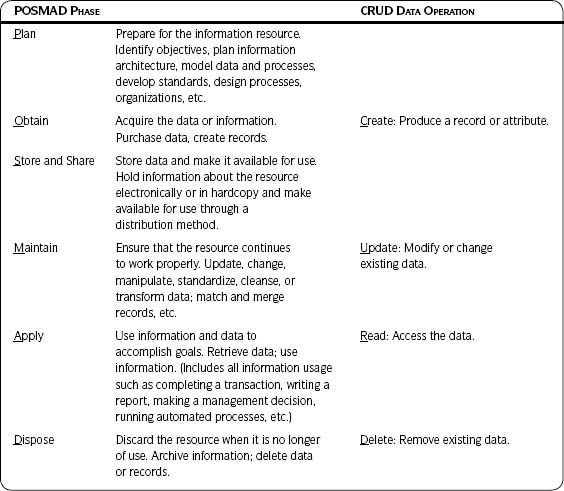

Those with a background in IT may be familiar with four data operations known as CRUD (Create, Read, Update, and Delete). CRUD indicates the four basic data operations—that is, how the data are processed in the technology. Many IT resources will relate to the CRUD point of view and you can learn valuable information about the POSMAD life cycle by discussing it in terms with which they are familiar. (It’s also a good idea to make them aware of the life cycle.)

If you are focusing on a business impact assessment, see how many programs relate to the Read phase of CRUD. This can also give you an idea of how the information is being applied.

Table 3.6 maps the six phases of the POSMAD life cycle to the four data operations (CRUD). It also illustrates how technology is just one aspect to be considered when understanding the Information Life Cycle.

Understanding how the POSMAD phases map to the data operations will help in tracing potential causes of data quality problems within the application—for example, if an issue is found during the Maintain phase when a knowledge worker is changing a record, a starting point for investigating possible technical causes would be the application’s update programs.

Table 3.6 • Mapping the POSMAD Life Cycle to CRUD Data Operations

3. Capture any impact to data quality that can be seen through understanding the technology.

For example, data may be moved between data stores using some kind of messaging technology. Mapping or transformation of the data takes place to put the data in alignment with the format required for messaging. Any time you have these changes you increase your chances of negatively impacting data quality.

You may also be looking ahead at the types of data quality assessments you will be conducting. Do you anticipate the need to purchase any tools to help in the assessments? What is the cost and lead time for purchase? What training will be needed? (See the Data Quality Tools section in Chapter 5 for a summary of data quality tools.)

4. Document results.

Capture any insights, observations, potential impacts to the business or to data quality, and initial recommendations as a result of this step. If you haven’t already created a form for tracking results, see the section Analyze and Document Results in Chapter 5 for a template to help you get started.

Step 2.4 Understand Relevant Processes

Business Benefit and Context

Focus on the processes that affect the quality of data and information throughout the six phases of the POSMAD life cycle—Plan, Obtain, Store and Share, Apply, and Dispose. (See the Information Life Cycle section in Chapter 2 for more detail.)

A quality assessment may look at some or all phases of the Information Life Cycle since the quality of the data is affected by activity within any of the six phases. A value assessment focuses on the Apply phase—those processes that apply and use the information. Applying the data means any use to accomplish business objectives.

For example, the data may be used to complete a transaction or it may be in the form of a report to support decision making. The data may also be used by an automated program such as electronic funds transfer where money is pulled from a customer’s account on the date a payment is due. Some may consider this IT use (and it is), but it is also a process on which the business depends.

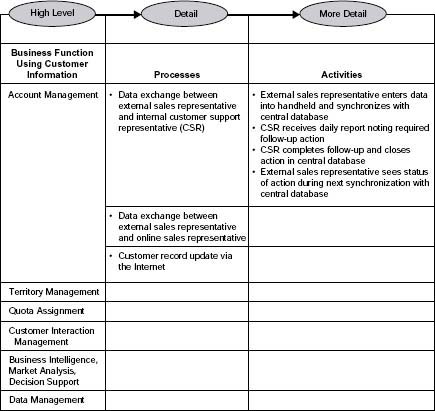

As with data, technology, and people and organizations, there are different levels of detail for processes. See Figure 3.6 for an example of an account management process. Only go to the level of detail necessary to explore the business need you are addressing.

Approach

1. List and identify processes at the appropriate level of detail.

Refer to the high-level business functions and processes described in Step 1—Define Business Need and Approach. Use these as your starting point.

Functions—Major high-level areas of the business organization (Sales, Marketing, Finance, Manufacturing, etc.) or high-level areas of responsibility (lead generation, vendor management, etc.).

Processes—Activities or procedures executed to accomplish business functions (e.g., “External sales rep enters customer data into handheld and synchronizes with central database” is one activity relating to the account management function). Processes can also be activities that trigger a response by the business (e.g., “Customer sends request for more information via company website”).

Function versus process is a relative relationship, with function being higher level and process being more detailed. What could be called a function in one project may be a process in another. Determine which level of process detail is most helpful at this time for your project.

![]() Best Practice

Best Practice

To determine relevance ask

- Which processes are affected by the business issue?

- Which processes impact the data relevant to the issue?

2. Determine the business functions and processes within scope.

List and describe those functions and processes associated with the business issue, the data, the technology, and the people/organizations within the scope of your project. Account for the activities throughout the Information Life Cycle at the level of detail to meet your needs. Research and use existing documentation related to the processes of interest.

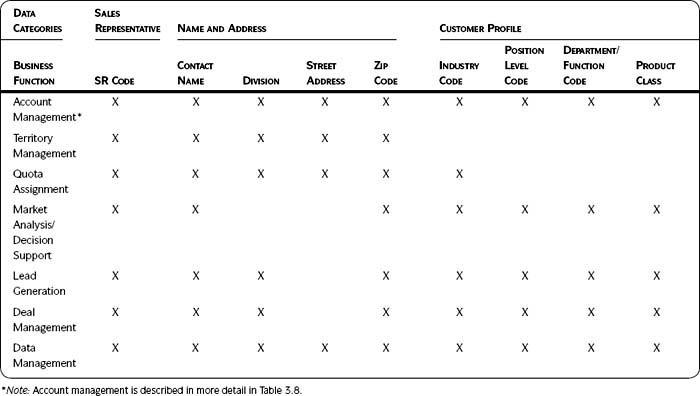

3. Relate the relevant data to the relevant business processes and indicate the life cycle phase or data operation taking place.

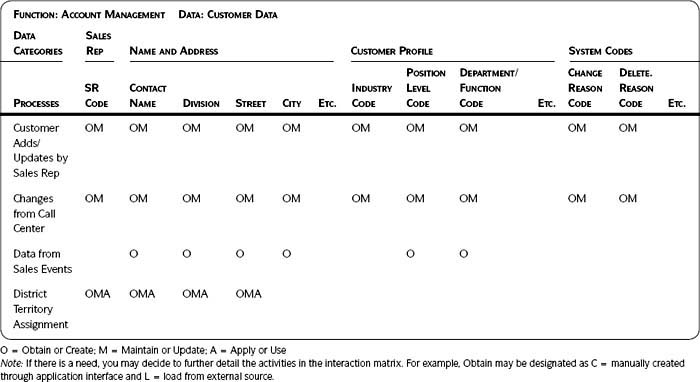

This can be done by creating a Business Process/Data Interaction Matrix. There are examples of two levels of detail in the Sample

Output and Templates section at the end of this step. Table 3.7 shows the interaction between business functions and data groupings. An X indicates where data are applied or used, but no further detail is provided.

Table 3.8 on page 97 uses one of the business functions, account management, from Table 3.7 and indicates which account management processes obtain, maintain, and apply the specific data. (Note that they chose to include only three of the six POSMAD life cycle phases.) You may need both or only one level of detail to understand your data. Using a matrix is just one approach.

4. Analyze and document results.

Look for patterns of similarities and differences across the rows and down the columns. For instance, in Table 3.8 there are four processes that obtain the data but only three that maintain them. Since data from sales events only result in adding records, there is a possibility that duplicates could be created. All processes that obtain and maintain data should be similar and training should be instituted to encourage consistency in data entry.

![]() Key Concept

Key Concept

Be aware that the actual output of the substeps in Step 2—Analyze Information Environment may take a different form than in the examples shown. For instance, for Step 2.4—Understand Relevant Processes, the output shown is in the form of a matrix. However, the output is not really a matrix; the output is knowledge about the processes and related data, how they interact, and how that interaction can impact data quality. Your output may physically take the form of a matrix, a diagram, or a textual explanation. The format used should enhance understanding. It is the learning that comes out of completing a step that is important. This applies to all steps.

Capture lessons learned, impact to the business, potential impact to data quality and/or value, and initial recommendations learned from analyzing processes.

Sample Output and Templates

In Table 3.7 an X indicates where data are applied or used during the associated business function. The function account management is further described in Table 3.8.

Table 3.7 • High-Level Function/Data Interaction Matrix: Business Functions That Use Customer Information

Table 3.8 • Detailed Process/Data Interaction Matrix: Account Management Processes That Obtain, Maintain, or Apply Customer Information

Step 2.5 Understand Relevant People/Organizations

Business Benefit and Context

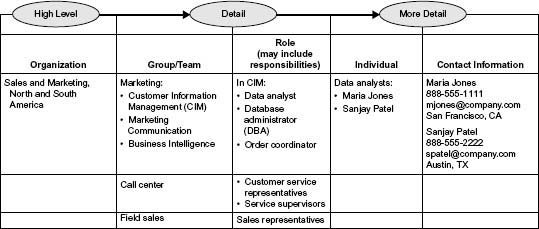

The purpose of this task is to understand people and organizations as they affect information quality and value. Choose the appropriate level of detail needed to meet your business needs (see Figure 3.7). Understanding organizations at a group/team/department level may be sufficient; knowing roles, titles, and job responsibilities may be necessary. At some point, knowing the individuals who fulfill roles of interest, along with pertinent contact information, may be needed as well. Remember, you can look at a higher level the first time through and go back for more detail later.

Connect Information Quality to Roles

Information roles fit into the POSMAD life cycle, and understanding the connection will lead you to people who can provide input to the project and impact to the data. Table 3.9 describes concepts about information roles that affect information quality. Understanding the concepts can help you look for people within your company who fit the descriptions.

Approach

1. Identify appropriate people and organizations.

Look at organizations, teams, roles, responsibilities, or individuals throughout the Information Life Cycle. Identify the various groups utilizing information relevant to your business issue. Gather and use existing documentation such as organization charts and job descriptions.

2. Relate the data to be assessed to the people and organizations.

An interaction matrix can be used to show how the various roles impact each of the data subject areas or fields. (See the example in Table 3.10 of this step.) The goal is to understand how the people and organizations impact the data or information. Use your best judgment as to the level of detail for both the people/organization axis and the data axis.

Table 3.9 • Information Quality Roles and POSMAD

3. Analyze and document results.

In Table 3.10, look at the rows across and the columns going down for similarities and differences. For example, one project team knew that many departments could apply or use the data, but they thought that only one could create or update them. Through this exercise the team found that people in other departments actually had the ability to create and update data as well. They could immediately see the impact to data quality: There were no consistent standards for entering data across the departments. Initial recommendations included looking at the organization to determine if it was appropriate to have create and update ability distributed across departments or if it should be centralized in one. At a minimum, all teams creating and updating data should have training.

![]() Best Practice

Best Practice

Identify Allies and Advocates: If you can identify people who may be suffering from data quality problems, they can be good advocates and sources of information to support many of your project activities.

Document lessons learned, potential impact to data quality and to the business, potential root causes, and initial recommendations in your results tracking sheet.

Table 3.10 • Role/Data Interaction Matrix

Step 2.6 Define the Information Life Cycle

Business Benefit and Context

In this activity, you will describe the flow of the Information Life Cycle POSMAD from planning or creation to disposal. The goal is to represent and summarize the life cycle by bringing together what you have learned about the data, processes, people/organizations, and technology. Focus on the POSMAD phases that apply to your business issue—Plan, Obtain, Store and Share, Maintain, Apply, and Dispose.

Understanding the Information Life Cycle is important to

- A quality assessment—All of the POSMAD phases affect the quality of the data. Your quality assessment will focus on those phases relevant to your business issues; therefore, you may choose to focus on only a few of the phases during your quality assessment.

- A business impact assessment—You will focus on the Apply phase—value is only received when the information is retrieved, applied, and used.

- An understanding of how the data currently flows—so you can better determine what to look at for each type of assessment.

The Information Life Cycle can be used to

- Develop new processes. Use the steps, techniques, and concepts to help you create a new life cycle that produces quality data, prevents quality problems, and increases the value of the information by promoting its use.

- Review current processes for improvement. This will show gaps, unexpected complexity, problem areas, redundant activities, and unnecessary loops.

- Further identify and improve key control activities needed. This will show where simplification and standardization may be possible and where to minimize complexity and redundancy (therefore minimizing cost) and maximize the use of the information (therefore maximizing value).

- Determine if associated people/organizations, technology, and data have been accounted for.

See Framework for Information Quality and Information Life Cycle sections in Chapter 2 for more background on the Information Life Cycle.

![]() Key Concept

Key Concept

The business receives value from information only during the POSMAD life cycle Apply phase—when information is retrieved, applied, and used.

Approach

1. Determine the scope of the Information Life Cycle.

If your project is for an initial assessment, depict the Information Life Cycle as it is currently, not as it should be. The life cycle will help show gaps, duplicate work, and inefficiencies that could be affecting the quality of information. You can use the “as is” view of the life cycle at a later time to change or improve it. If you are improving processes or creating new ones, create an Information Life Cycle that will fulfill your data quality and business needs.

Focus on the business issue affected by the information. You may be interested in the Information Life Cycle for a specific data subject area or for information used in a particular business process.

If a process/data matrix was created earlier (see Step 2.4—Understand Relevant Processes) look for pieces of information that have similar entries for the various data operations as one life cycle. Each type of information—for example, customer name and address or inquiries—could have a separate life cycle of its own.

2. Determine the appropriate level of detail for the life cycle.

Determine the level of detail needed to understand the process and identify problem areas. Your life cycle may be a simple high-level flowchart showing only sufficient information to understand the general process flow. Or it might be very detailed to show every action and decision point. If you are unsure which level is appropriate, start out at a high level and add detail later or only where it is needed.

3. Determine the approach for illustrating and documenting the life cycle.

Various methods for depicting the life cycle have been used successfully. For example, some process flows use a swim lane approach; others use a table approach. The approach you use will be influenced by the level of detail and the scope of your life cycle. (See the Information Life Cycle Approaches section in Chapter 5 for details, templates, and examples.)

4. Determine the steps in the life cycle and sequence them.

One technique is to write the life cycle steps on sticky notes or large index cards so they can be moved as the life cycle is developed. Place notes on a whiteboard and move them around until you are satisfied with the sequence and dependencies. This allows you to easily make changes as you go along. (Refer to the outputs from the previous substeps in Step 2—Analyze Information Environment.)

5. Document the life cycle.

Record the life cycle in a tool such as Visio or PowerPoint. Your company may have other tools available that will allow reuse. Remember to label and identify your work. Include the title of your process, the date the life cycle was created, any needed definitions or explanation, and so forth.

6. Analyze the life cycle.

The Information Life Cycle will show gaps, unexpected complexity, problem areas, redundancy, and unnecessary loops. It will also show where simplification and standardization may be possible. Note the hand-offs between operations. These are areas where there is potential for error, thus affecting the quality of the data. For example, the life cycle may show that more than one team is maintaining the same data. This is important to know so the business can determine if this is still the best organizational model. If so, the business will want to ensure that both groups receive the same training in data entry, updating, and the like. If the organizational model, roles, or responsibilities should be changed, the life cycle can help the business understand possible alternatives and serve as a high-level checklist to make sure various processes are being covered in the reorganization or realignment of duties.

If reviewed on a periodic basis, the Information Life Cycle will provide a systematic way to detect change. The life cycle can be used to answer the following questions:

- Has the process changed?

- Did any of the tasks change?

- Did the timing change?

- Did the roles change?

- Did any of the people filling the roles change?

- Did the technology change?

- Did the data requirements change?

- What impact do the changes have on the quality of information?

7. Document the results, lessons learned, possible impact to data quality and the business, and preliminary recommendations.

Capture what you have learned to this point. (See the Analyze and Document Results section in Chapter 5.) After the quality and/or value assessments have been completed, one of the recommendations may be to return to this step to create and implement a more effective life cycle.

Sample Output and Templates

See the Information Life Cycle Approaches section in Chapter 5 for ways to represent your life cycle.

Step 2.7 Design Data Capture and Assessment Plan

Business Benefit and Context

Based on what you have learned so far in this step, you are now ready to design how you will capture and assess the data. Capturing the data refers to either extracting them (such as to a flat file) or accessing them in some manner (such as via a direct connect to a database).

Approach

1. If needed, further prioritize the data to be assessed to fit within your project scope, schedule, and resources.

2. Finalize the population to be assessed and describe the selection criteria.

3. Develop the plan for data capture. Include:

- Data access method and tools required (For example, is there a front-end application currently in use that can provide the needed access or files?)

- Output format (For example, extract to a flat file, copy tables to a test server.)

- Sampling method

- Timing (Coordinate extracts across multiple platforms.)

- People who will be involved with the data extraction and assessment activities

Be sure to refer to the Capture Data section and Table 5.2 in Chapter 5 for additional information to help complete this step.

4. Develop the sequence for your data assessment.

5. Document the plan and ensure that those involved are aware of and agree to their responsibilities.

Step 2 Summary

Before starting on Step 2, you already knew something about your data, something about your processes, something about your technology, and something about your people and organizations. This step gave you the chance to bring together existing knowledge in such a way that you now better understand all these components and their impact on information quality. You delved into more detail when necessary and uncovered gaps where additional information needed to be gathered. This step gave you the opportunity to see all of this knowledge in new ways, and you have made (and will continue to make) better decisions about information quality because of it.

The main deliverables from Step 2—Analyze Information Environment include:

- Data capture and data quality assessment plan

- Results of analyzing the information environment

- Documentation with lessons learned (such as impact to the business, potential impact to data quality, suspected root causes, and initial recommendations discovered to this point)

Additional outputs that will be used during your assessments include

- Detailed data list

- Data specifications (enough detail to understand the structure and relationships of the data so data can be extracted correctly and assessment results can be interpreted)

- Detailed data mapping (if assessing more than one application/database or if source-to-target mappings for migrating data are needed)

- Requirements

- Information roles and their descriptions

- Information Life Cycle (at the level of detail appropriate to your needs)

- Updates to your communication plan

Tracking of results was mentioned at the end of every substep within Step 2. Take the time now to organize your thoughts and document your results if you have not yet done so. (If I mention it enough times you might actually do it!) Documentation gives you the ability to easily recall results. It provides a reminder of things to look out for when conducting your assessments—you will prove or disprove the opinions about the data you have acquired as part of analyzing your information environment. Documenting your observations and theories as they are discovered will save you time when uncovering root causes and developing specific improvement recommendations and actions.

![]() Communicate

Communicate

![]() Have management, business, and stakeholders been appropriately apprised of project progress?

Have management, business, and stakeholders been appropriately apprised of project progress?

![]() Are periodic status reports being sent?

Are periodic status reports being sent?

![]() Are all members of the project team aware of progress and of the reasons for the project?

Are all members of the project team aware of progress and of the reasons for the project?

![]() Checkpoint

Checkpoint

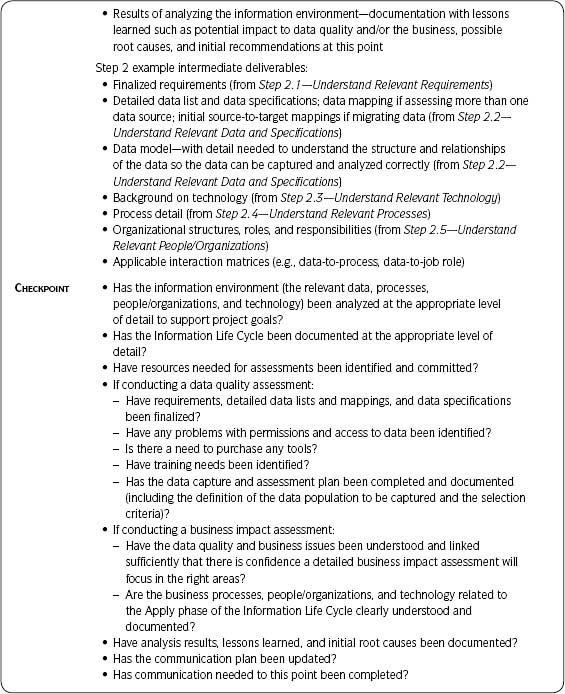

Step 2—Analyze Information Environment

How can I tell whether I’m ready to move to the next step? Following are guidelines to determine completeness of the step:

![]() Has the information environment (the relevant data, processes, people/organizations, and technology) been analyzed at the appropriate level of detail to support the project goals?

Has the information environment (the relevant data, processes, people/organizations, and technology) been analyzed at the appropriate level of detail to support the project goals?

![]() Has the Information Life Cycle been documented at the appropriate level of detail?

Has the Information Life Cycle been documented at the appropriate level of detail?

![]() Have resources needed for assessments been identified and committed?

Have resources needed for assessments been identified and committed?

![]() If conducting a data quality assessment:

If conducting a data quality assessment:

- Have requirements, detailed data lists and mappings, and data specifications been finalized?

- Have any problems with permissions and access to data been identified?

- Is there a need to purchase any tools?

- Have training needs been identified?

- Has the data capture and assessment plan been completed and documented (including the definition of the data population to be captured and the selection criteria)?

![]() If conducting a business impact assessment:

If conducting a business impact assessment:

- Have the data quality and business issues been understood and linked sufficiently that there is confidence a detailed business impact assessment will focus in the right areas?

- Are the business processes, people/organizations, and technology related to the Apply phase of the Information Life Cycle clearly understood and documented?

![]() Have analysis results, lessons learned, and initial root causes been documented?

Have analysis results, lessons learned, and initial root causes been documented?

![]() Has the communication plan been updated?

Has the communication plan been updated?

![]() Has communication needed at this point been completed?

Has communication needed at this point been completed?

Step 3 Assess Data Quality

Introduction

You have been introduced to data quality dimensions—aspects or features of information and a way to classify information and data quality needs. Dimensions are used to define, measure, and manage the quality of the data and information. (See the Data Quality Dimensions section in Chapter 2 if you need a reminder.) As noted in Table 3.11, Step 3—Assess Data Quality provides one substep with detailed instructions for each of the 12 dimensions of quality listed in Table 3.12 (see page 111). The assessments provide a picture of the actual quality of your data and information.

The most rewarding benefit of the data quality dimension assessment will be concrete evidence of the problems that underlie the business issue you identified in Step 1—Define Business Need and Approach. The assessment results also provide background information needed to investigate root causes, correct data errors, and prevent future data errors.

If by chance you decided to skip Step 2, please reconsider! Every successful project has needed to analyze the information environment in some form or another. Feedback from project teams confirms that analyzing the information environment is essential before quality assessments and is needed to ensure meaningful results. Start at a high level of detail and work down only if needed. It is much more efficient to get at least some background prior to your quality assessment.

Approach to Step 3

The overall approach to Step 3 is straightforward: First, make a conscious decision about which dimensions to assess; second, complete the assessments for the dimensions chosen; and third, synthesize the results from your assessments (if more than one data quality assessment is performed).

Choose the Data Quality Dimensions to Assess

Familiarize yourself with the various data quality dimensions and what is required to complete an assessment for each one. Revisit your project goals and the output from Step 1—Define Business Need and Approach. Ensure that the business situation and needs have not changed. If the needs have changed, make a deliberate decision to modify your data quality approach to meet the new needs and ensure that everyone involved is informed and supportive of the modifications.

Prioritize and finalize the appropriate quality tests to be performed. If you are considering several dimensions and need to minimize the scope to meet your timeline, prioritize the tests that will return the most value. Any investment in assessing data quality will yield valuable results, the long-term benefit will only be realized when the root causes of the issues found during the assessment have been addressed.

Assess Quality for the Dimensions Chosen

Become familiar with the details of each quality dimension chosen. Review and finalize the data capture and assessment plan from Step 2.7—Design Data Capture and Assessment Plan. You may need to modify the plan based on your current scope, timeline, and resources. You will need a data capture and assessment plan for each of the quality dimensions chosen. Use the detailed instructions for each dimension to help you complete its quality assessment.

Document the lessons learned, possible impact to the business, root causes, and preliminary recommendations from each quality assessment. (See the Analyze and Document Results section in Chapter 5.) Capture these results throughout the project, not just at the end. Almost everyone has had the experience where the team has a very productive working session, results are analyzed, and good ideas about root causes or impact to the business are discovered—but no one documents what was learned. Two weeks later everyone remembers the good meeting, but can’t remember the details. In the worst case that knowledge is lost and at a minimum time has to be spent to recover what was already learned. Capture those flashes of insight when they appear!

![]() Best Practice

Best Practice

Document results throughout the project, not just at the end. Use the template in the Analyze and Document Results section in Chapter 5 to get started. This will ensure that the knowledge and insight learned during each step are retained. It will save you time when specific recommendations and action plans are prepared.

Synthesize Results from Completed Quality Assessments

Combine and analyze the results from all of the quality assessments. Look for correlations among them. For example, if you conducted a survey of the knowledge workers’ perceptions of data quality, do those perceptions match the actual quality results from other dimensions assessed? Interpret the combined results and tie them into the original business issues. (See the Analyze and Document Results section in Chapter 5 for suggestions.) Document the lessons learned, possible impact to the business, root causes, and preliminary recommendations from all quality assessments performed.

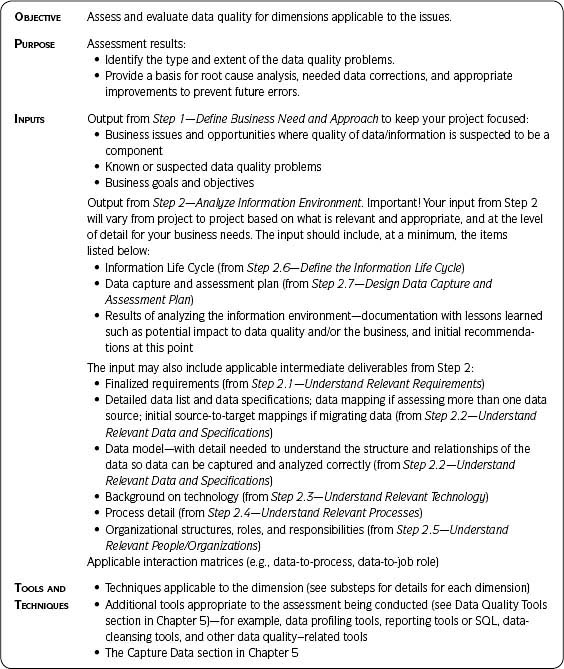

Table 3.11 • Step 3—Assess Data Quality

Table 3.12 • Data Quality Dimensions

Determine how the results of the quality assessment(s) will impact the rest of the project. Estimating the full project timeline before the assessment is difficult. The reason is that until you actually assess the data, you don’t know how large a problem you may have. What you find in Step 3—Assess Data Quality will impact the time needed for the remaining steps. Once completed you have actual results to determine your next steps and how they will affect the project scope, timeline, and resources needed.

Frequently Asked Questions about Data Quality Dimensions

Do Multiple Data Quality Dimensions Make Assessments more Complicated?

Having multiple dimensions actually makes the assessments less complex because you can

- Match actions against a business priority—choose only those dimensions that support the priority

- Perform tasks in the most effective order—assess dimensions in the most useful sequence with the result of

- A better defined and managed sequence of activities within time and resource constraints

- An understanding of what you will and will not get from the various quality assessments

How Do I Choose Which Dimensions of Quality to Assess?

When choosing dimensions of quality to assess, ask yourself these questions:

- Should I assess the data? Only spend time testing when you expect the results to give you actionable information related to your business needs.

- Can I assess the data? Is it possible or practical to look at this quality dimension? Sometimes you cannot assess/test the data, or the cost to do so is prohibitive.

Only assess those dimensions when you can answer yes to both questions! If you need help prioritizing, a useful technique can be found in Step 4.4—Benefit versus Cost Matrix. Table 3.25 (page 180) in the Sample Output and Templates section of that step lists decisions resulting from the use of the matrix to prioritize the data quality dimensions to be assessed. Don’t make this too difficult. Simply list each quality dimension, quickly determine the possible benefit to the business (high to low) and estimated/perceived effort (high to low), and map to the matrix. Don’t do in-depth research—make your best judgment based on what you know now.

The costs associated with assessing data quality dimensions can vary widely, depending on the dimension you choose to assess and whether you will use third-party data profiling or data cleansing tools. The best way to decide which dimensions to assess is to balance your business need against the resources available. Document the dimensions chosen, the rationale behind the decision, and the assumptions on which the decision was made.

Any Suggestions Regarding Which Dimensions to Assess First?

You will have already collected requirements in Step 2—Analyze Information Environment (see Step 2.1—Understand Relevant Requirements). Those requirements form the basis of Step 3.1—Data Specifications. You will need to take higherlevel requirements and turn them into the more detailed data specifications (or match them to already existing specifications) to ensure that you will be able to interpret the results of your data quality assessments. If you have concerns that the data specifications are missing or incomplete, you may want to start with Step 3.1.

In practice, at this point most people are ready to look at the actual data and do not want to spend time on more specifications and requirements. If you really can’t convince the team otherwise, at least have a minimum level of specifications and add to that as you go through your other assessments. If you begin data quality assessments with no requirements, just realize that the analysis will take longer as you gather the specifications needed to interpret your results.

It will not be unusual to find that poor-quality data specifications and business rules end up being one of the root causes of the data quality problems you find when assessing the other dimensions. Once you have proven the need for good data specifications, you can come back to this dimension. However, if you are fortunate enough to have support to start with data specifications, by all means do so!

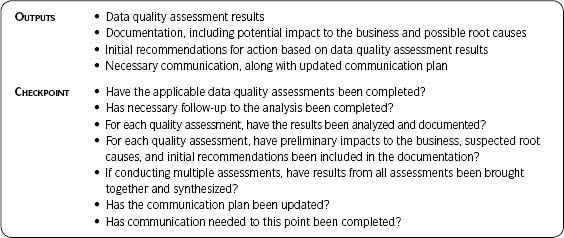

Once you have your data specifications (at whatever level of detail), it is strongly recommended that you start with Step 3.2—Data Integrity Fundamentals. These are fundamental measures of validity, structure, and content, and data profiling is a technique often employed here. If you don’t know anything else about your data, you need to know what this dimension provides. Often people will say they are really interested in accuracy or in understanding levels of duplication. Even if that is your end goal, you should still profile your data first.

For example, to determine duplication you have to understand which data field or combination of data fields indicates uniqueness. If you do not know the basic completeness (or fill rate) and content of each of the data elements, you can develop an algorithm for determining duplication based on fields that are missing the data expected or that contain data you didn’t know were there. These situations lead to incorrect duplication assessment results.