14

Global Leadership Development

Noel M. Tichy

An organization that develops leaders at all levels gains a competitive advantage in today’s global, increasingly knowledge-based economy. At the end of the last century, leaders won with brains, not brawn. Thus, in developing leadership, the dependent variable is honing leaders’ judgment capacity. In our book Judgment, Warren Bennis and I conclude that the essential genome of leadership is judgment. To make good leadership judgments, leaders need to develop skill and knowledge in three fundamental areas:

People —deciding who is on the team or off the team and how to develop those who are on the team.

Strategy —deciding what direction to take the organization.

Crises —dealing with the inevitable crises that all organizations face.

Figure 14-1 illustrates a framework for leadership development based on the process of enabling the leader to hone his or her capacity to make judgments. We argue that like medical doctors in training, leaders only really learn in a clinical practice—by actually making real judgments. This is why residency programs for young doctors are built around making clinical judgments. Even though a resident can make life-changing judgments, the residency framework does include some safety nets. Senior resident leaders and the head of residency provide continuous coaching and feedback. In the analogous case of action learning in companies, we create the equivalent of a residency program by giving teams of leaders real projects with real consequences, requiring the application and development of good business acumen, good leadership, and teamwork. To provide safety nets, the CEO frames and guides each project, and each team also has a senior leader coach and sponsor. Projects require both leaders and team members to follow good leadership judgment, as outlined in figure 14-1. The process of good judgment is the same whether the judgment concerns people, strategy, or a crisis. Because judgment is a clinical skill, it requires real clinical practice and feedback.

Figure 14-1. The Importance of Following Good Leadership Judgment During All Project Phases

| PREPARATION PHASE | CALL PHASE | EXECUTION PHASE | ||||

in the environment the future |

essence of an issue paramaters and establishes a shared language |

stakeholders energizes stakeholders from anywhere |

yes/no call the call |

yes/no call the call |

feedback Makes adjustments |

|

environment Fails to acknowledge reality instincts |

the issue ultimate goal old paradigm |

expectations people on board previous mistakes |

it’s time to make a call how issues intersect and how the call will play out |

the call is made important information what good execution requires |

outcomes to resistance in the organization mechanisms to make necessary changes |

Source: Tichy and Bennis, 2007.

This framework guides leadership development at all levels. For example, as a consultant at Best Buy, I worked with the store managers, who then tasked the young staff in the stores with defining the value propositions for customers, with teaching each other, running real-time experiments, reviewing daily profit and loss statements for their stores, making adjustments, and engaging in the critical process of hiring and firing colleagues. The goal was to develop good leadership judgment at the front line to drive performance and develop field-tested leaders.

At the associate level, the developing leaders needed to do a good job in the preparation phase by identifying emerging customer trends and needs, framing and naming the judgment that needed to be made, and then aligning key stakeholders to set up the call phase. The execution phase is equally important. At Best Buy, a key strategic judgment was the acquisition and growth of the Geek Squad to do home installations and provide computer services. Associates at the floor level saw the need and helped frame the judgment for the CEO, Brad Anderson, to buy the Geek Squad company and make it a part of Best Buy to support home installation and computer servicing. The execution phase was supported by an action learning project in 2002 that focused on how to better integrate services in the stores and grow the service business. This is now a multibillion-dollar Best Buy business. For another pertinent story that provides a framework for the discussion that follows, see the sidebar.

|

Historical Context: Action Learning as an Evolutionary Journey In the early 1970s, as a faculty member at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Business, I launched an executive program, Organization Development and Human Resources Management, based on an action learning model—so students could work on real change projects while developing as leaders. When I moved to the University of Michigan, I launched the Advanced Human Resource Management Program in 1981, which was an action learning, three-workshop platform for human resource leaders to lead transformations in their companies. This led to the creation of action learning programs at companies including Honeywell, Exxon, and Whirlpool, before I took over as head of GE’s fabled leadership center, Crotonville, in 1985. That experience set the stage for working with other global companies including MercedesBenz, Intuit, Royal Dutch Shell, Nokia, Numera Securities, Best Buy, Walmart, Pepsi, Ford, Mexico’s Grupo Salinas, and Thailand’s CP, among others, to design and build world-class leadership development. I have also worked with the Navy SEALS, hospitals, and school systems as they build their leadership pipelines. Surprising to some, the fundamentals translate across cultures, industries, and sectors. Thus this sidebar provides a framework for guiding the social architecture of a robust leadership pipeline that integrates senior leadership ownership, on-the-job leadership development, and powerful leadership development programs. GE’S Global Development Strategy: Crotonville Benchmark General Electric’s management development operation headquartered at Crotonville, New York, provides formal development experiences for GE professionals and managers worldwide. Each year, approximately 5,000 employees come to Crotonville’s 53-acre campus, which has a 200-plus bed residential education center. In the mid-1980s, while I ran Crotonville in collaboration with CEO Jack Welch, we changed its mission to focus on global development. The new objective became “to leverage GE’s global competitiveness as an instrument of cultural change, by improving the business acumen, leadership abilities, and organizational effectiveness of General Electric professionals.” From that point forward, Crotonville has served as a transformational lever for GE, as well as an individual leadership development tool. Therefore, many of the premises that guided CEO Jack Welch’s actions in the 1980s have generalized applicability to transnational companies around the world. The GE case illustrates how the training and development infrastructure of large companies can serve to bring about much more compressed, higher-impact change than currently experienced. Such global change will require that CEOs have a new mindset, similar to the one that Welch developed. He grasped that winning globally requires continuous employee development at all levels, ensuring that GE develops a culture in which the need for speed, continuous experimentation, and action is met. Welch perceived himself to be a leader of a major cultural revolution at GE. He had been looking for ways to best utilize GE’s Crotonville resources. In keeping with this imperative, one of the fundamental premises guiding the transformation of Crotonville during the 1980s was that revolutionaries do not rely solely on the chain of command to catalyze quantum change. They carefully develop multichannel, two-way, interactive networks throughout the organization:

The Crotonville Transformation Similar to most university business schools, the primary focus at Crotonville had historically been on the individual participant’s cognitive understanding. The shift in the Crotonville mindset has been from a training mentality to a workshop mentality, which ultimately leads to a completely new program design. It has resulted in a greater number of teams attending sessions whenever possible. Also, participants increasingly bring real business problems to the table and leave with real action plans. Before going to Crotonville, participants’ individual leadership behaviors are rated by their direct reports, peers, and bosses. The aim is for changes in leadership behavior to be linked back to the work setting. Other action learning tools include having executives consult real GE businesses on unresolved strategic issues. Teams spend up to a week in the field consulting with these businesses. In addition, members of the CEO’s team and officers come to Crotonville to conduct workshops on key GE strategic challenges. Along the way, participants find the development experiences increasingly unsettling and emotionally charged. They experience discomfort with the feedback from their back-home organization. They wrestle with very difficult, unresolved, real-life problems. They make presentations to senior executives, argue among themselves, and work through intensive team-building experiences that include a good deal of Outward Bound–type activity. The measure of program success shifts from participants’ evaluation of how good they felt about the learning experience to how the experience has affected their organizations and their own leadership behavior over time. For the Crotonville program to deliver on its new global mission in the 1980s, the total curriculum was revamped to provide a targeted “core development” experience at key career transition points for people at all levels—from new professional hires up through the top management offices. |

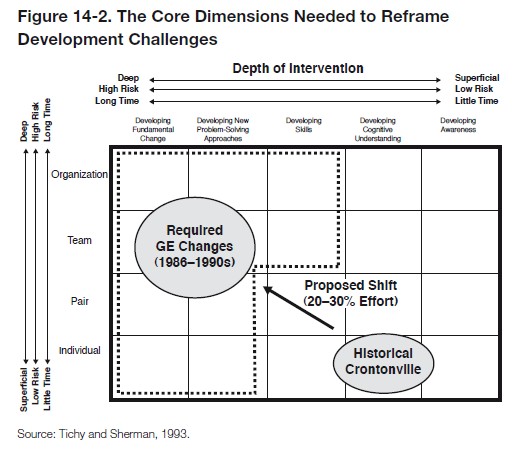

Figure 14-2 shows the core dimensions necessary for reframing development challenges. This figure illustrates the depth of the training solution. As solutions like these become deeper, leaders move from a focus on developing (1) awareness and (2) cognitive and conceptual understanding to (3) actual skills, (4) new problem-solving approaches, and ultimately to (5) fundamental change. The level of risk goes up at each stage. More time is required to develop the deeper training solution.

The other dimension in figure 14-2 is the focus (or target) of the training solution, with one end of the spectrum being anchored at the individual level and the other at the organizational level. Traditional programs commonly send individuals either to internal management development programs or to external business school programs. Occasionally, boss–subordinate pairs or two colleagues attend programs. Less rarely, but still part of the repertoire of traditional development programs,

Figure 14-2. The Core Dimensions Needed to Reframe Development Challenges

teams are sent, and finally, the target is sometimes the total organization. In contrast, the development matrix shown in figure 14-2 asserts that the challenge is to move development toward the upper left portion of the matrix, “developing fundamental change.”

Guidelines for Linking Development With Reality

When management development programs are reconceptualized as action workshops, real “live” problems, not case studies, command attention. People in the action experience are at real risk, and there are tangible organizational goals for transformation that are linked to the development activities. Add globalization to the agenda, and the model for successful compressed action learning becomes clear: intense cross-culture problem solving that requires multicultural teams, a faculty that is transcultural as well as multilingual, and breaking free of the classroom into real cross-cultural settings. Only when these cross-cultural teams of executives are required to deliver with real stakes and real risks involved, can there be a quantum development breakthrough.

As organizations compete on the global playing field of the 21st century, competitive leaders at all levels rise to a new level. The lessons learned in the past 20 years have led to the development of five guidelines for building the competitive leadership pipeline of the future. Leadership development is both on the job as well as in special programs. Thus there needs to be an integration of leadership development and overall talent and succession management that follows these five guidelines:

Articulate a teachable point of view.

Embrace the 80/20 rule.

Utilize action learning.

Move from the top down.

Build the rest of the leadership development institute.

Let’s look briefly at each guideline.

The First Guideline: Articulate a Teachable Point of View

The first guideline is to articulate a teachable point of view. The CEO and the top management team need to clearly articulate a teachable point of view for how the organization will succeed in the future. This includes the need to clearly articulate ideas (a global business strategy) and a set of values (how all employees need to behave to support the ideas; a set of assumptions about how to emotionally energize all employees by using rewards and consequences) and the ability to exercise yes/no judgments about people, strategy, and crises consistent with the ideas and values of the company. This teachable point of view must be embedded at all levels by leaders teaching leaders, not by outsourcing teaching to consultants and professors.

An example of this is Brad Anderson, who, when he was CEO of Best Buy, worked with the top management team to change the strategy from commodity, low-cost, volume selling of consumer electronics to a customer-centric model. The teachable point of view required new strategic ideas to segment the customer base, to identify key segments, and to develop clear value propositions for how to make money in major segments, such as high-end customers, female customers, and small business customers. This further required a new set of values for working with customers in the store, such as empowering store associates with the tools and freedom to solve customer needs. This teachable point of view was then made the framework for using an action learning platform to reach all 100,000 associates.

The Second Guideline: Embrace the 80/20 Rule

The second guideline is that the 80/20 rule must be embraced by the leadership. Because 80 percent of leadership development is on-the-job and life experience, designing career paths to build leaders is a critical task of senior leadership. Cross-functional, cross-cultural, and cross-business experiences with coaching, learning, and assessment at all stages are critical. The 20 percent that can be influenced by formal development needs to be extraordinarily effective, and thus the dial is turned up very high on action learning—for real projects with real results.

At GE, the 80/20 rule was tied to succession planning at all levels. The leadership team gave careful consideration to assignments of leaders for both the sake of the business and the development of the leader. Specific development agendas were articulated for leaders as they moved into new assignments, and they were tracked and reviewed systematically.

To implement the 80/20 rule at GE, we followed the set of guidelines shown in figure 14-3, the leadership pipeline audit, which highlights the important elements in building the leadership pipeline infrastructure in a company.

Figure 14-3. Leadership Pipeline Audit

| Leader identification | |||

| Score | |||

| Not at all | Definitely | ||

| 1. There are at least three viable contenders for each senior position on the team. | |||

| 2. Our leadership pipeline screens leaders for their Teachable Point of View. | |||

| 3. The leaders who are contenders to move up have demonstrated that the can develop other leaders behind them by creating Virtuous Teaching Cycles. | |||

| Pipeline architecture | |||

| 4. Deliberate development opportunities are created at each career stage. | |||

| 5. We have identified competencies and values required of future leaders, not those of the past. | |||

| 6. There is deliberate effort to ensure that leaders have a broad base of experience to understand the business (across geography, business unit, P&L apability, etc.). | |||

Source: Tichy and Cardwell, 2002.

To guide succession planning at GE, Jack Welch personally led an effort to define the leadership pipeline. When I was running Crotonville, GE’s leadership institute, Welch had my colleague, Don Kane, and I work with him and then–vice chairman, Larry Bossidy, to articulate what leadership characteristics were going to be needed in the future. Welch said, “However I got to be CEO is irrelevant: The world has changed, our values have changed, we need to create leaders for tomorrow’s world.” We spent more than 18 months with Welch and Bossidy discussing, debating, and agreeing upon what we wanted in the way of leadership characteristics across all of GE’s businesses anywhere in the world, whether Jet Engines, Medical Systems, or Capital. We incorporated interpersonal skills, functional/product skills, and organizational skills. Table 14-1 presents a summary of the framework.

This framework provided Welch, the CEO, as well as the heads of the businesses and the human resource staff with a template for position assignments. It was used in succession planning discussions throughout the company.

Developing a leadership pipeline for the company is not a consultant or staff activity; it is a CEO responsibility and needs to be done regularly as the world changes. The same fundamental process was used at Best Buy, Intuit, and Shell. It is not industry specific: It is a thoughtful, disciplined, strategic talent planning process.

The Third Guideline: Utilize Action Learning

The third guideline is to utilize action learning. Action learning entails simultaneous leadership development and work to solve real problems. If done right, you get 1 + 1 = 4:

1 [leadership development] + 1 [task force] = 4

(twice the impact on leadership development and twice the impact on task force results)

With action learning, there is better leadership development due to feedback based on the leader’s regular job, 360-degree feedback before the start of the program, and improvement plans and feedback from teammates during the action learning program, complete with rigorous

| Employee | Interpersonal Skills | Functional/Product Skills | Organizational Skills |

| Individual contributor | Build effective communication and relationship skillsEffectively deal with personal strengths and weaknesses | Develop specific functionalskillsLearn roles and relationships within the functional/product unitDevelop work planning,programming, and performance assessmentskills | Reconcile personal values withorganizational value systemUnderstand how his/her function and business relates to the entire companyGrasp role of the company in the global marketplaceLearn about customers and suppliers |

| New manager | Learn to delegate work and get things done through other peopleLearn to effectively appraise the performance of subordinates and secure their improved performanceAcquire and effectively apply team-building skillsLearn to share insights and values with others so that effect is multiplied | Acquire basic managerial skills, such as budgetingor program planning | Reconcile personal values withcompany’s shared valuesLearn to integrate work of unit with related units |

| Experienced manager | Develop negotiation skills and effectiveness in dealing with conflict situationsGain executive communication skills required for broad-scale communicationsIncrease ability to deal with ambiguity, paradox, and situations where there is not a single “right” answer | Gain deep, well-rounded understanding of allrelated functional skills in area of prime assignment | Develop strategic thinking skillsand the capacity to useboth inductive and deductive problem solvingLearn how to effectively implement organizational changeUnderstand the difference between what is best forthe customer and what iseasiest for the businessMaximize understanding ofglobal business dynamics and interfunctionalrelationships |

| General manager | Gain capacity to deal concurrently with multiple issues of increasing complexity and ambiguityDevelop a recognition that he or she cannot and should not try to solve all problems personallyBuild skill in framing problems for others to solveUnderstand how to maximize contributions ofindividual, team, and staffDevelop a recognition that asking for help is a sign of maturity rather than a weaknessDevelop the sensitivity to respond to the needs of others based on limited stimulus or cues | Refine broad perspective that extends to the well-being ofthe entire organizationSharpen analytical and criticalthinking skills for organizational problem solvingPlay an active role in the development of the vision for hisor her business | |

| Business leader | Learn to effectively exercise power in making those decisions that only the leader canmakeDevelop projection and extrapolation skills to deal with situations where he or she has no firsthand knowledgeDevelop sensitivity to the forces that motivate people to behave as they do | Develop multifunctional integration skills to manage abusiness based on profit and lossDevelop and effectively articulate the vision for thebusinessDevelop the capacity toconceive, not just adopt,changeDevelop an effective understanding of the dynamics ofthe industryDevelop a balanced posture between leadership of thebusiness and integration/cooperation among thefunctions or other businesses in the companyDevelop the capacity to effectively manage communityrelations |

Source: Tichy and Cohen, 1997.

improvement plans. In the equation on page 156, the second “1,” which represents the project task force, is better because it is inserted into a disciplined process led by the CEO and top management team.

The Fourth Guideline: Move From the Top Down

The fourth guideline is to move from the top down. The CEO and the top management team need to build their leadership institute from the “penthouse” down. That is, start with the CEO leading an action learning program by engaging six teams of about six senior up-and-coming leaders working on strategic projects owned and framed by the CEO and the top management team. The participants are selected and assigned to teams by the CEO and the top management team. This project and selection process typically take about a half day to a full day working with the CEO and the top management team. In addition, each team has a senior leader, a coach, and a sponsor who are just that—a coach and a sponsor, not members or leaders of the team.

Why top down? Because this approach intellectually and emotionally commits the top management team to action learning. These are strategic projects done by emerging senior leaders on topics they truly care about.

We have implemented this CEO-driven action learning program at GE Medical Systems, Numera Securities, Royal Dutch Shell, Ford, Intuit, the Royal Bank of Canada, Intel, Grupo Salinas, and CP in Thailand.

The Fifth Guideline: Build the Rest of the Leadership Development Institute

The fifth guideline is to build the rest of the leadership development institute. First you need to identify appropriate career transition points, similar to GE’s pipeline, and then you can design action learning experiences appropriate to leaders at that level.

To show how these five guidelines work in practice, let’s look at a very illuminating case study of action learning, the Global Leadership Program at GE.

A Case Study of Action Learning: GE’s Global Leadership Program

The GE Global Leadership Program is a change process designed to speed up the company’s globalization. The GLP simultaneously solves global strategic challenges while developing the global leadership and team skills of individual participants. This is accomplished through “compressed action learning.”

Compressed action learning puts teams (typically six to eight six-person teams) and individuals under extreme pressure to solve real organizational problems within tight time constraints, while activity paradoxically takes place in a supportive learning environment where there is time to learn new skills and concepts, which then are immediately put into practice to solve strategic challenges.

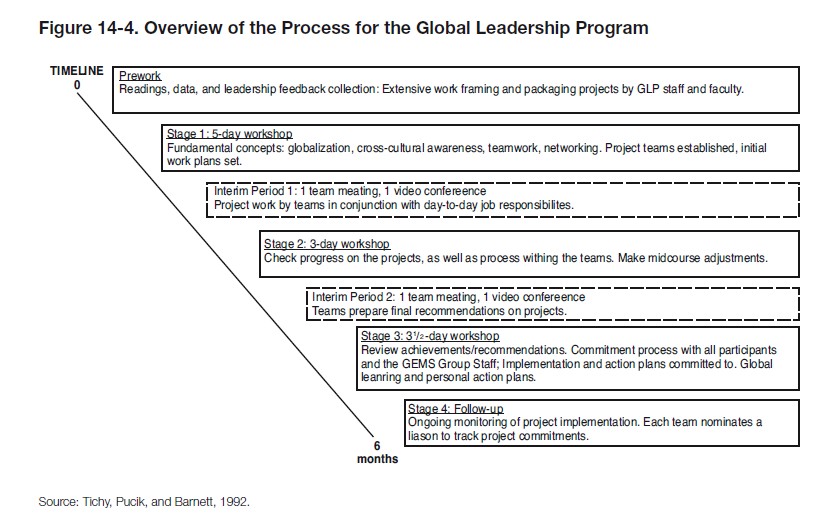

The GLP is led by the CEO and the senior management team, whose members actively participate as coaches, project sponsors, and active participants in the commitment change process. The GLP’s nine-month process starts with senior managers selecting key global projects, then selecting teams from different regions of the world (see figure 14-4). Before the first of three workshops, each selected individual goes through an extensive personal assessment as a global leader that includes having surveys filled out by six to eight colleagues on specific global leadership behaviors. Each GLP participant receives feedback on how he or she is seen by self versus how others see him or her. The first workshop lasts five days and is aimed at launching the global teams, getting the strategic projects under way, and starting the journey to develop more global mindsets and networks.

Following the first workshop, teams return to their regular jobs while simultaneously working on their global projects. There is a midcourse, three-day workshop to give help and feedback on the projects and to work on team processes, share best practices, and get coaching support.

The final step is an intensive commitment workshop. The participants work with senior managers focused on each project for a half day to review their achievements and realizations, work through the recom

mendations, and make real implementation commitments. In addition, time is taken to assess the “soft” human global leadership learning.

The final workshop, stage 3 in figure 14-4, has four objectives.

Run the best global meeting ever.

Make commitments to implement recommendations from all projects.

Continue global individual, team, and organizational learning and development.

Prepare for passing learning to the next GLP group of participants.

The final workshop is a change implementation meeting. The team assignments were given because they are critical to the company’s global success. The leaders of the company are asked to help make change happen. Therefore, the final workshop is an opportunity to mobilize a critical mass of leadership to implement a change plan. It is designed to help get people to buy in through discussion, debate, compromise, and ultimately by commitments to implementation.

The design of the final workshop is not a typical “old way” company presentation. It is a “new way” high participation process for the company leaders to take ownership of all the projects (typically six to eight); see table 14-2.

Each team’s written report should recommend a concrete action plan with specific steps to make change happen. The text should be no longer than 15 pages plus exhibits. The reports should include

mission

methodology

analysis of issue(s)

recommendation(s) for action (1 page)

specific action steps: who, what, when, and so on (1 page).

The recommendation(s) should deal with the real challenge of change— the technical, political, and cultural domains. The object is to have real change happen.

| “Old Way” | “New Way” |

| No reports ahead of time No preparation by nonpresenting teams Formal “pitch” Little debate Passive audience All energy focused on the boss No one has ownership | Written report prepared for everyone Reading and preparation ahead of time Minimal formal “pitch” Thorough discussion/debate Real-time modification to improve recommendations Total GLP commitment and “buy-in” to make change happen Continuous learning and development |

Source: Tichy, Pucik, and Barnett, 1992.

A responsibility of all GLP participants and the group staff is to read each of the reports before the presentations. It assumes that the global leaders within the company have ownership of all the GLP projects and are prepared to help with implementation.

Table 14-3 summarizes the leadership impact of the program.

The GLP is both a lever for transforming the company and a powerful leadership experience. A unique set of building blocks, or social technologies, is used in the GLP to achieve the results. There are five primary goals for the GLP:

Deliver on the global projects—to make changes in the company.

Develop global mindsets.

Develop global leadership skills.

Develop global team skills.

Develop global networks.

The GLP is delivered by creating a temporary system, that is, building a social organization with its own structure, leadership, and values.

| Impact on the Senior Leadership Team: • A global team-building process—The Global Leadership Program forces teamwork through selection of projects, guidance of program, and then commitment to take action. • A tool for developing global leadership skills—senior leaders are tested and learn as leaders in a global context. • Global role model—the group is on “stage” in the final workshop—making decisions publicly and demonstrating global leadership. |

| Impact on the overall organization: • GLP is an R&D lab for new global behaviors; experimentation and learning are key to GLP. • Global networks are formed and reinforced across the poles of Asia, the United States, and Europe. • Global information sharing—best practices. • Assessment mechanism for succession moves. • External viewpoints/benchmarks—from global faculty. |

| Impact on individual participants: • Develop a global mindset—new ways of framing business power. • Global leadership skills practiced and developed. • Global team skills practiced in program. |

Source: Tichy, Pucik, and Barnett, 1992.

Compressed action learning puts individuals and teams under intense time and performance pressures. They must deliver strategic change to the company while acquiring new skills and immediately use them to deliver on the projects.

One problem I uncovered at Crotonville, and was aware of for years looking at business school executive programs, was what I call the plug-in module approach. In a four-week executive program in most universities and corporate universities, one day might be spent on strategy, another on finance, marketing, team building, leadership, and so on. These modules often stand alone and are not connected to application. This is akin to a medical student taking chemistry, biology, physiology, and so forth in medical school and only combining that knowledge when the student becomes a resident making real clinical judgments.

Action learning is a platform for learning multiple lessons over time about self, leadership, teamwork, and organizational acumen while applying them along the way in solving real-life problems. One reason for the six-month process is that the projects can be much more robust, giving time for benchmarking and working with key constituencies. It also provides another learning platform—overload. We use the action learning platform, which adds 25 percent above and beyond the participant’s regular job, as a way to teach and coach time management and delegation. Participants receive coaching from their regular bosses as well as the sponsor and faculty.

At each stage, action learning appropriate to the level is used as the developmental driver. For example, at GE we had a three-day workshop for 2,000 mostly young engineers. They came to learn about global competition, GE’s strategy, GE’s values, and how to get their careers off to a fast start as individual contributors. They had to come to Crotonville with an improvement project to which their bosses had agreed, such as quality improvement or a work process improvement. As you move up the hierarchy, projects get broader and broader, but they all have the same criteria—importance to the organization at that level, being jointly owned with the boss, and having measurable consequences—or else they fail the reality test.

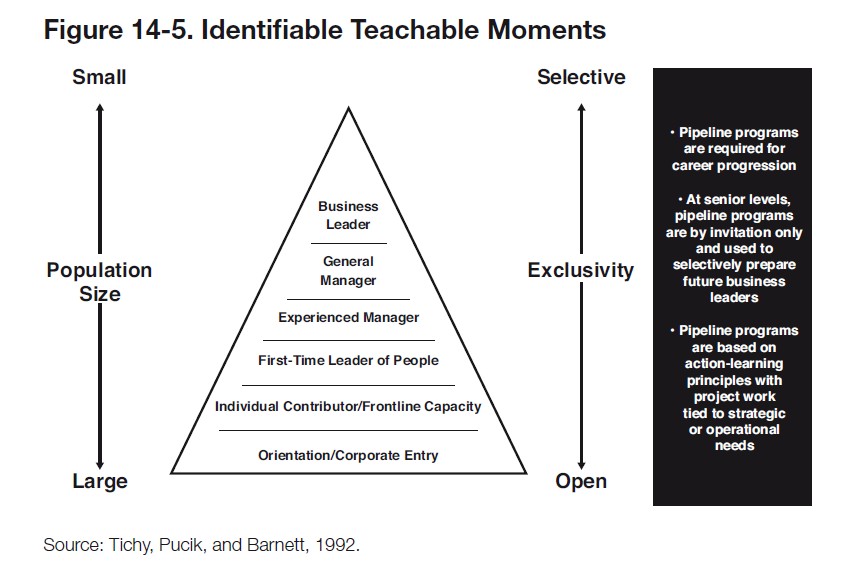

The identifiable teachable moments portrayed in figure 14-5 are typical of the careers of the leaders in most large organizations. They start with new hires, where there is an opportunity to imprint the company’s values and culture as well as fundamental work skills. For first-time leaders, there is an opportunity to imprint on them as they transition from being individual contributors to leaders of other people. Key elements are how to hire, appraise, develop, build a team, teach values, and deal with difficult people issues.

The next level in most organizations is the midlevel manager function, which involves programs aimed at broadening finance, human resources, IT, manufacturing, and other functional leaders. We then

move to the broader leadership population, which in large organizations requires a second-level action learning program below the strategic one described above. Rather than focus on strategic global issues, this program focuses on broadening the leaders to work cross-functionally. The teams are typically made up of multifunctional members who work on organizational improvement projects such as getting manufacturing to cooperate better with engineering or improving the relation between marketing and sales. The skills here are more along the lines of organization development skills than global strategic skills.

Conclusion

The demands on global organizations are going to get tougher and tougher. For Google, Facebook, or older line companies such as Micro-soft, Infosys, Lenovo, and the GEs of the world to compete, they must look at tomorrow’s leadership pipeline. The leadership pipeline is not limited to the middle and top of the organization but also runs from individual contributors to the next CEO. The more the frontline employees are using their brains to come up with new products and services— which is the case at Google, Amazon, and Best Buy—the more important it becomes to have a frontline-to-CEO leadership development pipeline. This requires the CEO and top management team, with involvement and support from the Board of Directors, to own the process as both social architects and leader-teachers using action learning platforms. Once a CEO grasps the 1 [leadership development] + 1 [task force output] = 4 formula, with twice the return on both, the battle is won. In my experience, the CEO then becomes available for teaching, which in turn sheds a light on the whole organization, and leaders at all levels then become leader-teachers.

Further Reading

Kane, Donald, Noel Tichy, and Eugene Andrews. 1987, November. “Organizational Effectiveness Whitepaper: A Leadership Development Framework.” Unpublished.

Tichy, Noel. 1983. Managing Strategic Change: Technical, Political and Cultural Dynamics. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Tichy, Noel. 2003. “The Death and Rebirth of Organizational Development,” chapter 10 in Organization 21C. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Financial Times Prentice Hall, 2003.

Tichy, Noel, and Warren Bennis. 2007. Judgment: How Winning Leaders Make Great Calls. New York: Penguin Group, 2007.

Tichy, Noel, with Warren Bennis. 2007, October. “Making Judgment Calls.” Harvard Business Review. Available at http://www.noeltichy .com/pdfs/HBR.pdf.

Tichy, Noel, with Nancy Cardwell. 2002. The Cycle of Leadership: How Great Leaders Teach Their Companies to Win. New York: HarperCollins, 2002.

Tichy, Noel, with Eli Cohen. 1997. The Leadership Engine: How Winning Companies Create Leaders at All Levels. New York: HarperCollins, 1997. Tichy, Noel, with Mary Anne Devanna. 1986. The Transformational Leader.

New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Tichy, Noel, with Andy McGill. 2003. The University of Michigan Business School’s Guide to the Ethical Challenge: How to Lead with Unyielding Integrity. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Tichy, Noel, with Vladimir Pucik and Carole Barnett, eds. 1992. Globalizing Management: Creating and Leading the Competitive Organization. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Tichy, Noel, with Stratford Sherman. 1993, January. Control Your Destiny or Someone Else Will: How Jack Welch is Making General Electric the World’s Most Competitive Company. New York: Doubleday/Currency.

Welch, Jack, with John A. Byrne. 2001. Jack: Straight from the Gut. New York: Warner Books.

About the Author

Noel M. Tichy is a professor of management and organizations at the Ross School of Business at the University of Michigan, where he is the director of the Global Business Partnership, which for more than a decade ran the Global Leadership Program, a consortium of 36 companies around the world that partnered to develop senior executives and conduct action research on globalization. In 2003, he launched the Global Corporate Citizenship Initiative in partnership with General Electric, Procter & Gamble, and 3M to create a national model for partnership opportunities between business and civil society. To encourage leadership development, he has partnered with a variety of medical systems, the Boys & Girls Clubs of America, and two charter schools in Texas. He also conducts a leadership judgment executive workshop at the University of Michigan. In the mid-1980s, he was head of GE’s Leadership Center, the fabled Crotonville, where he led the company’s transformation to action learning. Before joining the University of Michigan faculty, he served for nine years on the Columbia University Business School faculty. He is the author of numerous books and articles. His most recent book, with Warren Bennis, is Judgment: How Winning

Leaders Make Great Calls (Penguin Group, 2007). He has also co-authored a number of other books, including Michigan Business School’s Guide to The Ethical Challenge: How to Lead with Unyielding Integrity (with Andrew McGill; Jossey-Bass, 2003); and The Cycle of Leadership: How Great Leaders Teach Their Companies to Win (with Nancy Cardwell; HarperCollins, 2002). He has long been regarded as a staple of management literacy, as noted by his rating as one of the top 10 management gurus by BusinessWeek.