1

Introduction: Too Many Soloists, Not Enough Music

Kevin Oakes and Pat Galagan

The term “talent management” is such an enigma. In an industry like learning and development that consistently reinvents its vocabulary, never before has a human resources term garnered so much attention and yet been so misunderstood and overly hyped—and, by some, overly scorned. Ironically, given the many articles, books, presentations, and rhetorical efforts that have been devoted to it over the years, talent management remains a mystery to most.

So why did we decide to add to this proliferation with this book? Our years of observing and opining about the learning and development industry led to growing puzzlement and some persistent questions related to talent management:

How does organizational talent become a capability?

Why do so many otherwise exemplary companies continue to acquire, develop, and deploy their talent with isolated practices that, if put together and coordinated, could become so much more effective?

Why do so many leaders proclaim that people are their most important asset but then not manage this asset from a unified perspective?

Why do organizations go to so much trouble to acquire the best talent, only to keep those soloists in private studios and never assemble the orchestra for virtuoso performances?

Our perspective comes from observation, research, and conversations over many years. Our two organizations—the Institute for Corporate Productivity (i4cp) and ASTD—have collected data through multiple studies of how companies acquire their talent, how they develop it and manage it, and what works and what doesn’t. Between us, we’ve had conversations with thousands of people whose professional lives center on the effort to make organizations perform better through their people.

Often there is understandable logic to the way companies approach the acquisition and development of talent today, but typically it’s an approach built on the avoidance of pain—the pain of breaking familiar patterns and doing things differently. So whole industries behave this way, following rigid and outmoded practices like these:

the five-year plan

the selection of people with high potential by some calcified numerical formula

succession planning that ignores the reality of a mobile work force

recruiting in a vacuum

development divorced from strategic direction.

You probably have your own list of talent-related practices that no longer make sense in a fast-moving world.

Abolishing Silos

Herein lies the real puzzle. Although many companies know that talent matters for growth as well as survival, managing it as a coherent strategy is still very rare. Despite all the attention paid to the idea of talent and its management—remember the “war for talent” breaking out nearly 15 years ago?—the practices surrounding it are largely unchanged. In many companies, even several with dedicated talent officers, talent management is still regarded as just another term for succession planning and executive development. And though research clearly shows that functions such as performance management are most easily integrated with learning and development, why do so few companies actually integrate them?

We’ve seen too many companies whose talent management practices continue to be stuck in silos—a metaphor, we like to point out, from the agricultural era. In today’s knowledge worker era, these silos, all under the umbrella of HR, often have their own agendas, compete with each other for available budget, and actively work against each other to gain political power. We believe that this too-common reality in companies is not only immature but also unproductive. True integration is long overdue and deeply necessary. Even the talent management pundits and zealots will secretly admit that there are too few examples of companies that are actively and successfully integrating the silos. For practical ideas on how to do this, see the sidebar.

|

Slicing Through the Silos With Software By Kevin Oakes Almost a decade ago, the overly anxious CEO of an HR technology company began pitching to me the idea of merging his company with my company to form the ultimate entity: a complete talent management suite. At the time, I was CEO and chairman of Click2learn, a leading learning management company (I would later merge Click2learn with Docent to create SumTotal Systems). The landscape of human capital technological solutions was still very nascent, but the idea of a suite of applications that would address all aspects of HR had, for a few years, already been envisioned by many in the learning and development industry. This particular CEO was not the first to approach me with the idea of joining forces, but he was easily the most aggressive. His pitch: “Together, we can be the only provider to offer end-to-end HR and learning products and services in the attain–train–retain continuum. let’s seize this opportunity now, and drive the market!!!” is the way he ended one memorable email. The problem, as I unconvincingly kept describing to him, was that the potential buyers in corporations are in silos. Very few—if any—companies at the time were positioned organizationally to take advantage of such a holistic solution. Almost all firms ran their HR groups separately. Their recruiting people couldn’t have cared less about their performance management people—who often fought for budget with their learning and development people—who were typically not even in the same building as the compensation and benefits group. In short, we could preach all we wanted, but there was no one congregation ready to hear our message. Today, the landscape has changed. Though the preaching has only increased in volume over the years, companies now are much more prepared to take advantage of the fully integrated talent management technology suite. And technology providers finally are ready to deliver, primarily because of what that aggressive CEO wanted in the first place: the merging of complementary companies. You probably remember some of the names: DigitalThink, Thinq, Pathlore, GeoLearning, Learn.com, Centra, Interwise, Softscape, RecruitForce, Resumix, Hire.com, BrassRing, Vurv, Salary.com. You and I could list hundreds more. The obvious commonality among these companies, of course, is that they all were purchased. But their maybe-not-so-obvious similarity is that they all, arguably, were considered “point solutions,” addressing and excelling at only a small portion of the talent management life cycle. Today’s mergers-andacquisitions activity is all about seeking the holy grail of the fully integrated talent management suite, a quest that no vendor—despite the propaganda—has yet to fully achieve. But that’s quickly changing. The talent management field is maturing both technically and in helping corporations realize how to use integrated talent management for their strategic benefit. However, the term “talent management” is still thrown around too loosely by suppliers. It’s no wonder that buyers get confused. As this book goes to print, I’ve just returned from an investor conference featuring several human capital vendors. Almost every single CEO and chief financial officer talked about their firm’s strength in “talent management.” I witnessed the CEOs of two staffing companies say they were “leaders in talent management.” Their definition obviously differs from ours in this book. Although mergers in general help achieve the technical functionality needed, the benefits of a merger often take much longer to take effect than projections claim. The truth is that most firms tend to be strongest at their roots. Thus, not only are vendors more technically capable with their original products, but it’s also how they think. If you are a hammer, everything looks like a nail, so most firms continue to approach the market from the mindset that helped them succeed in the first place. Although this situation is an understandable and natural fact of this talent evolution, buyers need to be prepared for it as they begin to adopt the integrated talent management suite. There will be strengths, and there will be weaknesses, and many will be based on the heritage of the vendor. The “complete suite” is unlikely to be truly complete for some time, and as a result, many companies will continue to integrate multiple vendors’ products to achieve the functionality they need. This evolving integration, whether between vendors or within one vendor’s complementary applications, typically centers on mapping data between human capital functions. And the data most in demand are the skills and competencies of the workforce. A common refrain from corporate practitioners is, why can’t I centrally store the skills of job applicants when they are hired, and pass those to the performance function along with the skills deficits that we identified, and they in turn pass data on to the learning function, which ties into the compensation function? Up until recently, the answer was lack of data integration—both among the technology platforms and modules currently on the market and among the HR functions. Integration continues to be the primary challenge in the learning and development industry, according to a study conducted by ASTD in cooperation with i4cp. Only 19 percent of the respondents said that their companies integrated talent management components to a high or very high extent, and only one in five said their firm has the technological capability to do so. Though capabilities keep getting added, the easiest prediction to make is that integration will continue to be an issue for years to come. However, when it comes to integration, the same study found that the two components integrated the most in successful implementations were the learning and development function and performance management. This is the easiest place to begin in many companies, because these functions naturally go hand in hand, and several providers of technological solutions focused on this link early in the development of their integrated suites. Identifying performance issues, and recommending learning and development opportunities that address those issues, is a hallmark of good performance management, but it’s amazing how many companies don’t do this today. In the future, it’s easy to envision these two functions never being separated, but today it’s still rare to see them completely integrated. Other core elements that are germane to top integrated talent management programs include leadership and high-potential development, retention, and engagement. Although the integration of talent management poses many challenges, it’s important to point out the core strategies that organizations can follow to improve their chances of success in integrating:

Advances in software as a service, cloud computing, and an increased understanding of data mapping are helping to make the integration of talent management easier and are allowing companies to see the light at the end of the tunnel when they will be able to take full advantage of the integrated talent management suite. This, according to our research, will benefit the bottom line of corporations by leveraging internal talent more strategically. Although the learning and development industry will never be at a loss for preachers willing to deliver this particular sermon, there’s obviously still much missionary work left to do. |

Yet despite the generally sad state of talent management, the landscape is slowly changing. In our recent work, we have come across several corporate practitioners and industry experts who have success stories to share—sometimes small, sometimes revolutionary—which frankly are what encouraged us to create this book.

However, we started this project with an admitted bias: From our research and observations, it is clear to us that the learning and development function has a critical role to play in integration. We firmly believe that all the traditional HR silos can and should be integrated on some level with learning and development. Therefore, we explicitly invited the contributors to this book to reflect our perspective. Most actually did. By and large, the authors of the chapters that follow highlight how a particular silo or HR function is integrated into the whole of talent management and how it utilizes learning and development to be more strategic and productive for the organization.

Definitions Abound

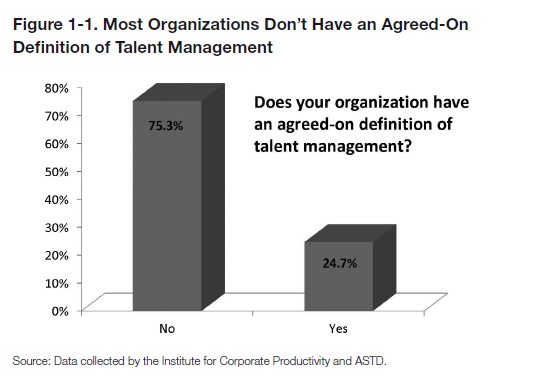

It’s amazing that today, more than a decade since the term “talent management” was introduced, nearly everything spoken or written about it still starts with a definition. Many of these definitions, including some that we’ve written, are so comprehensive that they verge on being incomprehensible. Though this may be a symptom of a practice undergoing growing pains, it has only added to the confusion. The upshot is that most organizations don’t have an agreed-on definition of talent management (see figure 1-1).

Most of the definitional issue centers on which HR components are to be included in integrated talent management. And this is one part of the confusion that makes sense. Not every organization has the same kinds of talent challenges. Some need frequent fresh supplies of frontline workers who are quickly ready to serve customers. Others need seasoned engineers who can innovate in highly competitive, technical fields. Many need versatile global talent who can develop into the leaders of the future. And all need their talent to turn on a dime when events such as deep recessions and market upheavals change the rules of the game.

Source: Data collected by the Institute for Corporate Productivity and ASTD.

On the basis of our research into the various human capital functions that reside in companies today, we identified six key components of talent management:

recruiting

compensation and rewards

performance management

succession management

engagement and retention

leadership development.

We organized this book so that each of these components constitutes one section containing two or three chapters addressing important aspects of the topic. Yet though these six topics are the major practice areas that corporations typically cite as making up their integrated talent management strategies, that doesn’t mean they are the only ones for your organization.

In chapter 2, Wharton professor Peter Cappelli provides a logical way to think about what components of talent management to emphasize. You’ll note that his choice of components differs somewhat from ours. Let that be fair warning: This is not a book of rules. It’s a collection of viewpoints and working practices described from two angles—the thought leader’s and the senior practitioner’s. Accordingly, the first chapter in each section reflects on research-based theory informed by many years of observation and thought, and the second (and in one case third) chapter describes practices under way in large, successful enterprises.

A Menu, Not a Recipe

As you pursue integrated talent management in your organization, when deciding which components to emphasize, your obvious choices will be the functions that will most quickly put the right talent in the right jobs at the right time. So it won’t matter if your effort is “disproportionately” focused on top executives, or key scientific jobs, or super sales generators—as long as it makes strategic sense and supports your key business goals.

Moreover, despite our bias for integrating the role of learning and development, we aren’t campaigning for the primacy of one component over another. In the chapters that follow, you’ll see from the practitioners’ accounts that while finding, developing, and keeping talent are common to all the companies featured in the book, most emphasize one component over another for reasons that make good business sense to them.

At 3M, for instance, where innovation is the lifeblood of the organization, there’s a strong focus on engaging people and encouraging them to stretch (see chapter 13). At Edwards Lifesciences, where CEO Michael Mussallem drives a culture of execution and accountability, talent management focuses strongly on succession planning, to put at least two candidates in line for every key job (chapter 11). And at GE, the überincubator of leadership development in our time, the emphasis is on “judgment capacity” arrived at through industry-leading practices such as leaders teaching leaders and action learning (chapter 15). From Hertz’s focus on rewarding knowledge transfer (chapter 7), to Cisco’s linkage of performance plans to the CEO’s vision (chapter 9), to Agilent’s embracing of evidence-based HR (chapter 3), this book is full of both practical examples and strategic viewpoints for today’s corporations.

Although similarities abound, every company is unique. Therefore, we’re not strict constructionists when it comes to processes, as long as you have one for stitching things together around the common goal of better performance. And that’s really what this book is about: achieving higher organizational performance and workforce productivity through optimized talent management.

Every chapter describes a talent management process in both theory and practice for the component it covers. And the authors address how to integrate these processes with other talent management efforts in other parts of the organization:

linking skills uncovered in the recruiting process to the succession planning process

leveraging compensation plans to create a pay-for-performance culture

enabling greater employee engagement for greater corporate innovation and less unwanted attrition.

Thus, the authors of the following chapters reveal what is working for their high performance organizations, and how others can adopt these practices. We invite you to join the conversation.