CHAPTER 3

State of the Practice

To better understand how expert judgment is employed in the project management context, a global study of project management professionals was conducted.

3.1 Method

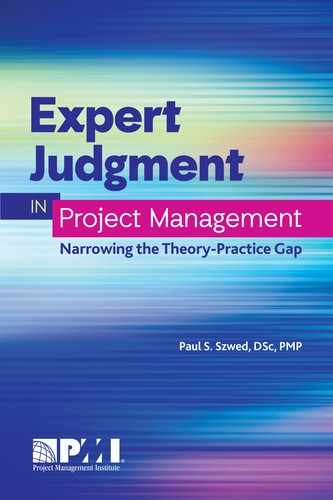

This phase of the research examined the state of the practice of expert judgment in project management. Figure 8 illustrates the model being explored by this study.

A descriptive survey was selected as an effective means to gather information that is not easily observed (Buckingham & Saunders, 2004). The survey was developed in 2013 and underwent institutional board review and then blind peer review according to the sponsoring organization’s grant process. (See Appendix A for a complete listing of the instrument.) The survey was designed to do the following:

- Determine current expert judgment practices in the project management context.

- Compare expert judgment practices across different industries and regions.

- Elicit best or effective expert judgment practices.

In order to achieve those objectives, two categories of questions were developed. The first group of questions gathered demographic information about the project management professionals (e.g., job function, experience, certification) and the context within which they work (e.g., industry, location, policy, and process). The second group of questions gathered expert judgment practice information (e.g., usage, process, tools).

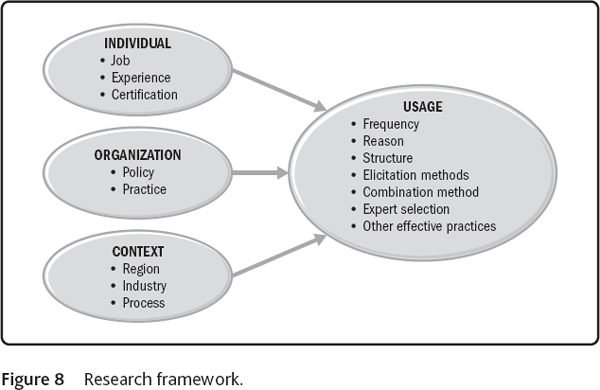

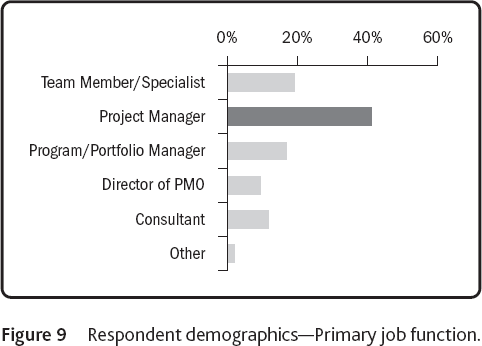

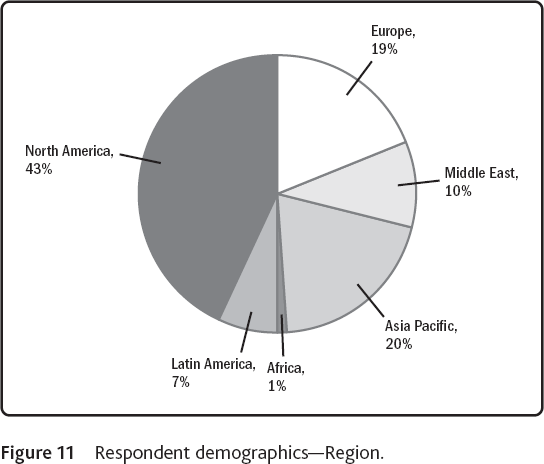

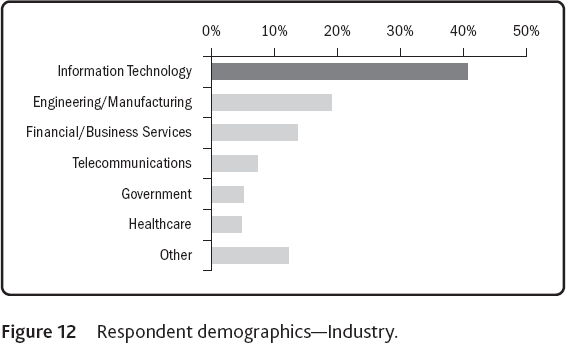

3.2 Data and Sample

An online survey was administered during the second half of 2014. It was posted to the Project Management Institute’s website during the first four months. The Project Management Institute is the largest global professional society for project and program managers with more than 450,000 members; it has 273 chartered chapters in 105 countries (Project Management Institute, 2015). Because there was insufficient response resulting from the passive deployment and because survey participation is declining in general (Kennedy & Vargus, 2001), in November and December, the survey was sent electronically to each of the chartered chapters requesting that the survey be shared with their local membership. This direct appeal, using a modified Dillman technique (2011), yielded 449 responses to the survey, of which 382 were complete (i.e., a completion rate of 85.1%). Figures 9 through 12 provide a summary of the demographic data. The most frequently occurring responses (i.e., the modal response) have the darkest shading.

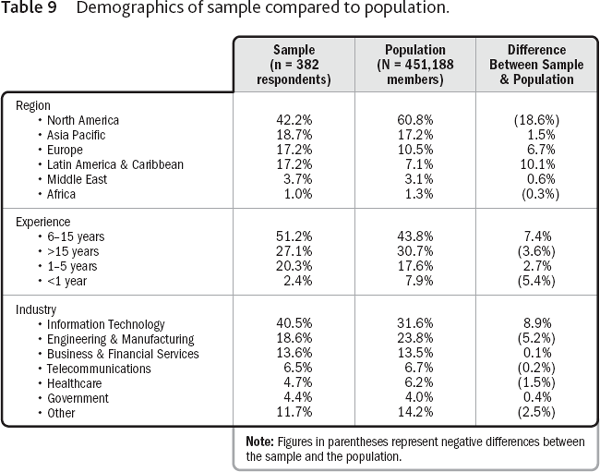

This sample is approximately representative of the population for the professional society membership (K. Dunn, personal communication, January 15, 2015). Table 9 describes the demographic breakdown of the sample as compared to the population from which the survey was drawn.

In general, the sample did not suffer coverage sampling error (Couper, 2000). The sample was slightly overrepresented in respondents from Europe and Latin America (and significantly underrepresented in North America—an increasingly common result [Cook, Heath, & Thompson, 2000]). The distribution of experience level of the respondents was representative of the population. Adjustments were made for the categories of experience to facilitate comparison. Additionally, the sample was moderately overrepresented in respondents from the information technology industry. Overall, the order of relative representation was consistent between the sample and the population, which illustrates an adequate sample (Groves et al., 2011).

3.3 Analysis and Results

Because this phase of the research set out to determine the state of the practice, the descriptive summary results were as important as the analytical results. First, it was observed that a vast majority of respondents (95.1%) indicated using expert judgment for the projects they manage.

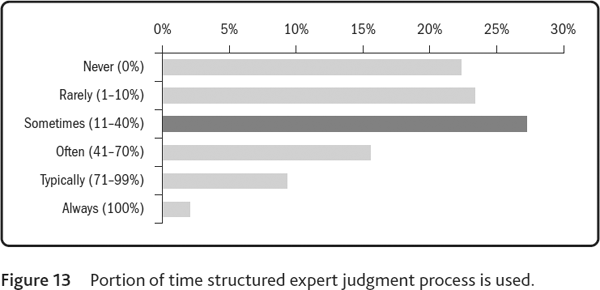

Since one of the underlying motivations of this entire research project was to determine if the practice of expert judgment in project management is ad hoc and ill-defined (as suggested by the limited definition), one of the most important questions in the survey was “How often do you use a predefined structured process for eliciting expert judgment?” Figure 13 provides a summary of responses to that question.

Respondents were provided a scale of frequency (on the lefthand side of Figure 13) with which they indicated how often they used a structured process for the elicitation of expert judgment. The majority of respondents (almost three quarters) used a structured process infrequently or not at all. If these responses were combined, we would see that expert judgment is only elicited 25.5% of the time using a predefined structured process. Therefore, expert judgment is not usually elicited using a predefined structured process. Overall, just one in 10 project management professionals uses written guidance for eliciting expert judgment.

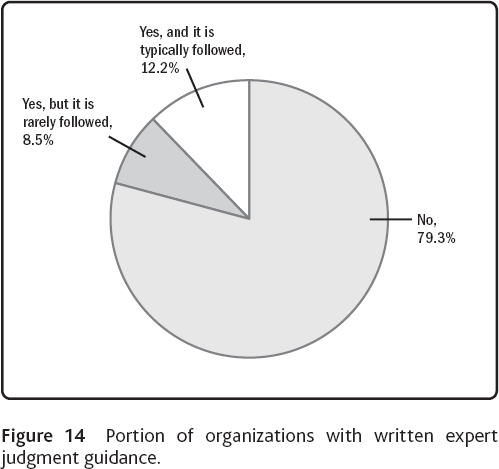

Figure 14 describes whether or not the organizations within which the respondents worked offered written guidance on expert judgment elicitation.

Almost four out of every five respondents worked in organizations that did not have any written guidance on expert judgment. Of those who responded that they did work in an organization that had written guidance, only about 60% indicated that the guidance was typically followed. The other roughly 40% indicated that the guidance was rarely followed, effectively indicating that 87.8% of respondents had not used written guidance about eliciting expert judgment.

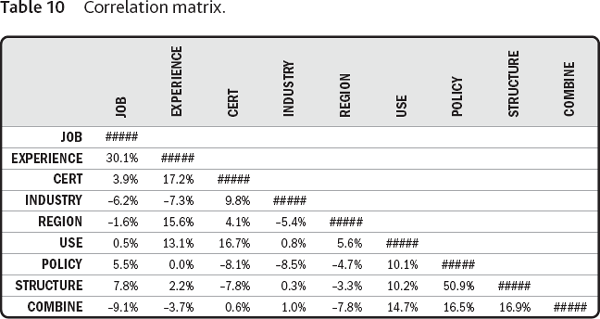

Several of the hypotheses suggested relationships between demographic variables and practice variables. Analysis of variation (ANOVA) was performed, and Table 10 provides the correlation matrix. All of these values were tested at the 95% significance level.

There was not a significant relationship between project management experience and frequency with which a predefined structured elicitation process was used. Therefore, there was insufficient evidence to support the idea that the usage of a predefined process was independent of and not correlated to project management experience. Note also that there was no correlation between the region where the respondent project manager worked and whether a predefined structured process for eliciting expert judgment was used. Therefore, there was insufficient evidence to support the notion that the usage of a predefined process was independent of and not correlated to the region in which the project manager worked.

Observing the strongest correlations, the greatest is the 50.9% association between whether or not an organization has written guidance on expert elicitation and how often a project manager uses a predefined structured process for eliciting expert judgment. This was the strongest correlation and marginally upheld the notion that the use of a predefined structured process increases when an organization has written guidance for conducting expert judgment elicitation. The next strongest was between project management experience and job function. Although not a part of this study, this relationship could be expected because as project managers gain experience, they likely move from serving on a team to leading a team to leading several teams to leading an organization.

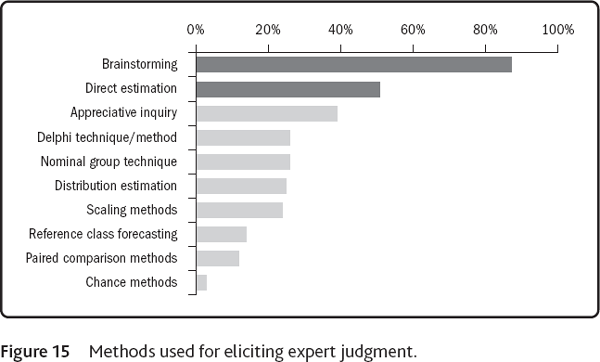

Figure 15 provides an overview of the most frequently used expert judgment elicitation methods; brainstorming and direct estimation were the two most frequently used.

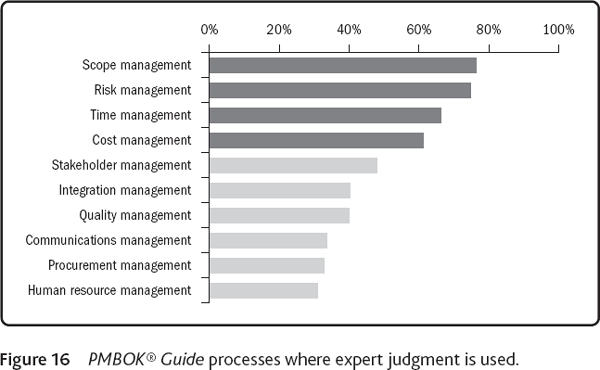

The Project Management Institute publishes a set of guidelines that includes standard definitions, terminology, processes, and procedures for conducting project management. The most recent edition of this 589-page foundational standard, known as A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) – Fifth Edition, was published in 2013 and was organized into 10 Knowledge Areas. Figure 16 provides a summary of the Knowledge Areas, where expert judgment is most frequently used according to the survey results.

There was no correlation between the expert judgment processes (seen in Figure 16) and the methods used (seen in Figure 15).

3.4 Limitations

There were several limitations to this study. Some are common to survey methodology and others are unique to this study.

3.4.1 Population

Because the survey was posted to the Project Management Institute website on Survey Links and later sent to local PMI chapters, the population of the survey was taken to be the membership of the Project Management Institute or its local chapters. At nearly half a million members strong, the population was concentrated on members of the Project Management Institute. Even though PMI is the largest professional society and provider of certifications devoted to the advancement of project management, this study neglected the vast number of project management practitioners who are not affiliated with PMI, who may work independently of a professional membership organization, who may work with a different organization, or who may possess other credentials. Future studies may consider alternative populations to identify and confirm differences in practices.

3.4.2 Sample Randomness

The set of respondents was not a purely random sample in that the respondents were voluntary in nature and were not selected at random from the population. For a probabilistic data sample, one would need to target specific project management practitioners drawn randomly from the population. Without access to a master database of Project Management Institute members, this is not possible. Therefore, a chi-square test of goodness of fit was performed for each of the demographic variables provided in Table 9 to determine whether the region, experience, and industry of the sample was representative. The proportion of respondents from each region was not equally distributed in the population, χ2 (dof = 5, N = 392) = 95.3, p > 0.005. The proportion of respondents from each level of experience was equally distributed in the population, χ2 (dof = 3, N = 392) = 11.5, p > 0.005. The proportion of respondents from each level of industry sector was equally distributed in the population, χ2 (dof = 6, N = 392) = 17.3, p > 0.005. Therefore, this sample was representative of the population at large across all but one of the demographic dimensions (i.e., region). This was largely because of the fact that the sample was significantly underrepresented for North America and overrepresented for Latin America and the Caribbean.

3.4.3 Sample Size

Despite 449 responses (of which 382 were complete), the sample represents less than one tenth of 1% of the population. The sample size was sufficiently large to analyze, but in the case of certain subsets (e.g., specific industry sectors or regions), the sample may have been too small for fine analysis. Therefore, most of the findings will focus on the entire response rather than examining responses of specific demographic elements. This was the scope of the study, and the analysis indicated that there were not statistically significant differences between subgroups (when size permitted this analysis).

Furthermore, because this was a pilot study (since a similar practice survey of expert judgment in project management has not been published), it is not possible to ascertain the actual effect size in order to conduct a formal power analysis. However, if we make some assumptions about anticipated effect based upon knowledge of the state of the practice of expert judgment in project management, we can perform a post hoc power analysis. To demonstrate, we will examine the portion of time a structured expert judgment process is used (see Figure 13). In practice, we would conservatively expect project management professionals to use such a process “more often than not” (or roughly 65% of the time), which would yield a mean response of “often” on the survey scale. In reality, respondents indicated that, on average, they used a structured process “sometimes” (or about 25% of the time, with a standard deviation of about 30%). If we assume the standard significance probability of 5% and set statistical power at the recommended level of 0.8 (Cohen, 1992), our post hoc power analysis would indicate that such a sample size (n = 382) would yield a power approach 1.0, meaning that it would correctly reject the null hypothesis when it was false.

3.4.4 Self-Reported Data

Based on its nature, this survey relied on the self-reporting of respondents regarding their practices. Though many have noted that self-report data is inherently biased and validity suffers as a result, there is an increasing body of evidence to support the use of self-report data (Chan, 2009; Specter, 2006). Also, although the interpretation of the terms of the survey may have varied between industries, regions, or applications, efforts were made to standardize the terminology and anchor it to the project management body of knowledge and lexicon. Additionally, the survey was field-tested using a think-aloud protocol to identify interpretation issues. Adjustments were made to help alleviate the interpretation issues.

3.4.5 Scope of Study

This survey was descriptive in nature and was focused on identifying the current state of the practice of expert judgment elicitation in project management. Explanatory research, which attempts to explain the reasons behind certain phenomena, was not conducted in this study. This may be a topic of future investigation.

3.5 Findings and Implications

There were several key findings in this descriptive survey that helped to shed light on the state of the practice:

- Expert judgment is widely used in project management. Over 95% of respondents indicated using expert judgment for the projects they manage.

- In most instances, expert judgment is conducted in an ad hoc manner. Almost three quarters of respondents indicated that they used a predefined structured process sometimes, rarely, or never (i.e., less than 40% of the time).

- Most practitioners work in organizations that do not have specific policies about using expert judgment. Only one in five respondents indicated he or she worked in an organization with written guidance for expert judgment elicitation.

- Most (57%) practitioners will use the written guidance for conducting expert judgment elicitation when it is available. Therefore, currently, only one in 10 project management practitioners uses written guidance to elicit expert judgment.

- There is a moderate correlation between the presence of written policy on expert judgment elicitation and practitioner use of a predefined structured process.

- Brainstorming, a free-form technique for generating ideas, is by far the most commonly used expert judgment tool/technique. Eighty-seven percent of respondents indicated using brainstorming for conducting expert elicitation.

- Practitioners use expert judgment most frequently during scope, time, cost, and risk management processes. Respectively, 76%, 66%, 61%, and 75% of respondents reported using expert judgement in these processes (as compared to less than 50% reporting using expert judgment in the other process groups).

These findings strongly suggest that there is an opportunity to improve the state of the practice when it comes to using expert judgment in project management.