A shooting script is the detailed plan for a proposed film. Sometimes called a “shot list,” it consists of a description of each shot to be incorporated into the picture.

Though largely supplanted by the master scene script (see Chapter 13) where the writing of feature films is concerned, the shooting script remains more or less standard in the fact film field. In effect an instruction sheet for technical people and talent, it tells the actors what to say and do; the crew, what to take pictures of. In major measure, it determines what the audience will see when they view the finished film.

Because these things are so, the shooting script should at all costs avoid (a) pictures which confuse the audience, and (b) instructions which confuse cast and/or crew.

To this end, you need to learn how to break down action, how to describe shots, and how to set up a shooting script in proper format.

1. How to break down action.

The first step in writing a shooting script is to break down each sequence from your sequence outline into its component individual shots.

The trick here is to get in the habit of projecting the finished film in your head as you write it. Visualize each scene in careful detail as it develops. Watch the flow of action in your imagination.

Simultaneously, break down said action into shots: single runs of the camera.

This is a knack, believe me. The simplest way to master it, in my own experience, is to make contact with some amateur or professional worker in the field who will grant you the loan of some reels of edited film, a couple of film winds, and a tabletop rear screen projection device called a viewer. You then wind the film back and forth through the viewer, as slowly as need be, until you’re aware of shots as shots, not just a flow of action. Or, in a pinch, you can rent a couple of videotapes and play small segments over and over and achieve much the same effect.

Indeed, there are worse ways to learn to write a shooting script than to maneuver yourself into involvement in the process of film editing, whether as participant or as observer. Watching, watching, watching over some old hand’s shoulder as he labors at editing bench or Moviola, asking as many questions as you can get away with as to where and why he’s cutting, can prove a major step in your education as a scriptwriter.

Another possible though tedious procedure is to sit through the screening of a feature half a dozen or more times, till you’re so totally bored with the story that you can see the cuts—that is, the individual shots.

In any event, and whatever route you take: Do learn to see not-yet-filmed action in your mind’s eye.

Simultaneously, keep asking yourself, “What do I need to have the audience look at next?”

Your primary guideline in answering this question is of course the point you’re trying to make in the particular sequence: the subassertion it’s designed to prove. This is why it’s so devastatingly important that you write a sequence outline before you start your shooting script, whether anyone demands such of you or not. Without it, you can wander in endless circles, getting nowhere. It’s a major reason for films that drag and jerk and ramble.

So: What do you need to have the audience look at next? A tight closeup that will call some crucial detail to their attention? An establishing or reestablishing shot, far enough back to orient them to the broader action? A reaction shot, to help shape their attitudes?

And always, the issue will be the subassertion you’re trying to back with visual proof.

Break the question down, if need be. Consider such matters as

— What point am I trying to make in this shot?

— How does said shot tie in or relate to the point I’m trying to make in the sequence? In the film as whole?

— What should the action be, in order to make the point most convincingly?

— Am I forgetting anything, leaving something out that needs to be included?

Again, a guideline: The answer, in one word, is always pertinence … logical fitness, applicability, relevance. Every shot should be designed to intensify the effect you seek.

Visual pertinence … shots that sustain the flow of action or impression.

Emotional pertinence … shots which create the audience reaction you seek.

Naturally, in a host of instances—perhaps most—these tend to overlap. But both are elements you create with malice aforethought… products of thinking, pre-planning, floor-pacing, organization … calculated selection and arrangement of action/footage. And while a large part of the responsibility for the finished product of necessity falls on director and/or editor, the fact remains that the writer plays a major role just by the way he blocks things in. The better he understands film principles, the more likely he is to come up with a script that offers the other people involved ways to put an effective presentation on the screen.

a. Problems of visual pertinence.

Visual pertinence consists of visual flow honed razor-sharp with applicability to the point you’re trying to make.

In the continuity sequence, the issue will be to maintain the flow of action. To this end,

1. Coverage must be functional. That is, image size and angle must fit the needs of viewers where the particular situation is concerned. Thus, at certain times, it’s essential to orient your audience by establishing the relationship of characters to the background and to each other. At others, the action and/or appearance of characters and/or objects are what’s important. Or, the issue may be attention to certain key details.

The writer must anticipate these needs, this functional aspect of visual continuity, and provide for them in the script.

2. Coverage must be logical. Here the issue is less viewer needs than viewer desires, anticipations. If a character gives sudden, intent attention to his watch, Viewer is going to want to see the watch face. If murky shadows stir, Viewer will want to see what’s stirring; or, perhaps, Character’s reaction to it. If Character races down the street, Viewer will want to see what he’s pursuing, what’s pursuing him, or what hazards lie ahead.

3. Coverage must give the illusion of continuity. Confusion is a grave sin indeed in the continuity sequence. Change of angle, image size, or the like must be motivated, as when the camera jumps from a position aside and behind a running character to aside and ahead, in order to prepare for his sudden veering into an alley. It must also be substantial enough not to appear accidental. Yet on the other hand, it must not take so great a leap as to leave the audience groping as to where the action is taking place, who’s who, or what’s going on.

The shots must also be so smoothly joined that no break in the action is apparent.

To this end, continuity sequences are developed in terms of match cuts and cutaways.

A match cut is one in which the second of two shots of continuing action includes part of the action in the first shot. The shots are cut together where the action overlaps in a manner to insure smooth transition from shot to shot.

The cutaway, in contrast, does not include any part of the preceding shot.

Thus, we might open with a shot of an office, complete with desks, chairs, filing cabinets, and the like, but devoid of people. A door opens. A man and woman enter.

A second shot gives us a closer view of the pair. Woman moves a few steps further into the room. Shot 3 concentrates on Man as he closes door. Shot 4 sees Man cross to Woman. They embrace. Man unbuttons top button of Woman’s blouse. A fifth shot zeroes in on the doorknob, out of frame in shot 4. Knob turns slowly.

Since shot 2 includes part of what was seen in shot 1, it’s a match cut. Shot 3 includes part of what was seen in shot 2—again, a match cut. Shot 4? Another match cut.

Shot 5, however, was not included in shot 4. In consequence, it’s a cutaway.

The value of the cutaway in maintaining the illusion of continuity is beyond measure. Among other things, cutaways can successfully mask spots where the flow of action in two shots doesn’t quite mesh together properly. They can introduce parallel lines of action. They can clarify situations. They can break up an otherwise static scene. They can add suspense. They can speed up time passage.

Take our example. The cutaway of the doorknob introduces a parallel line of action, breaks up what might otherwise be a static scene, adds suspense. Perhaps, if we have been wondering what’s become of some other character, it clarifies the situation. If, after the cutaway, we cut back to Man and Woman and discover that three of Woman’s blouse buttons are now unbuttoned, we’ve speeded up time passage. And if this new shot reveals that Man is doing the unbuttoning with his left hand, when he was using his right in shot 4, we’ve also masked a break where two shots don’t cut together properly.

Visual pertinence operates a little differently where the compilation sequence is concerned—for in such, unity is provided by topic and narration.

In consequence, the goal in cutting often is to avoid the impression of continuity, continuing flow of action. Shots very well may be chosen for contrast, with emphasis on dissimilar colors, dissimilar sizes, dissimilar objects or action. Extreme closeups may be juxtaposed with extreme long shots, high angles with low, books with bursting bombs, people with machines or monsters.

So much for visual pertinence. In and of itself a fascinating subject, it rates intensive study on the part of every would-be screenwriter. The best place to carry out said study is in the cutting room, under the tutelage of an experienced film editor. Lacking the opportunity for that, much can be learned from the books in Appendix C.

b. Building emotional pertinence.

Emotional pertinence—shots which create the audience reaction you seek—is at least equally vital to visual, in that it has in it the power to make interesting what might otherwise be dull footage. Indeed, when someone tells you that you need to “build” a particular sequence, what he often means is that you need to add shots that will give it greater emotional pertinence.

You give a sequence emotional pertinence through your control of (1) time, (2) emphasis, and (3) reaction.

Take time. In a typical factory tour—live, not filmed—90 per cent of the actual, chronological time may be waste motion devoted to chitchat, bad jokes, walking from department to department, and so on. To include it in a film is to reduce effectiveness via boredom. Therefore, in building the tour from sequence outline to shooting script, you eliminate such immaterialities, leaving only essentials to be filmed—a montage that catches the key action in each unit, perhaps.

Emphasis may be the issue where a new widget-stamping machine is concerned. Though each step in its operation occupies only a fraction of a second, one particular meshing of gears or junction of parts is tremendously important. Made aware of this by your research, you break the overall process down, filling the screen with strong, pertinent extreme closeups which emphasize the details to which you want to draw attention. The split second involved in the actual stamping thus may end up stretching to a minute or more on the screen.

Or consider a continuity sequence in a home accident film. Our hero, disgruntled after a fight with his wife, goes out to move a heavy trunk from the garage to the basement via an old-fashioned outside stairwell. A broom lies across the threshold. Tossing it into the basement, and more irked than ever, Hero begins backing down the steps, bracing himself against the trunk’s weight. Past him, as we watch from above, we can see the broom, now caught crosswise across the stairs close to the bottom.

Cutting back and forth between man and broom, emphasizing each in turn, we can prolong Hero’s descent to an endless agony of suspense: Will he trip? Will he fall? Will the trunk crush him? Witness Alfred Hitchcock’s famous Psycho scene of Tony Perkins stabbing Janet Leigh in the shower; it built through 78 shots!

Reaction? In a compilation sequence, it quite possibly will be provided by a narrator, who in effect tells the audience what to think, how to interpret the mixed shots on the screen. Or, perhaps a dialogue interchange between actors calls attention to the emotionally pertinent points.

In the same way, a reaction factor can be injected into a continuity sequence on squirrel hunting by appropriate interpretation via narrator. Or, the reaction—and emotional pertinence—may be supplied by the enthusiastic behavior of the hunters themselves.

So much for the principles and procedures by which you build a shooting script. Now, on to mechanics:

2. How to describe a shot.

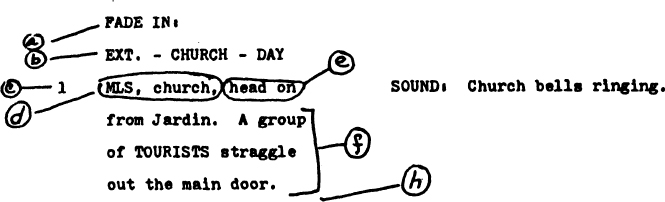

For clarity’s sake, let’s work from a sample, checking it against eight points:

Now, our checklist:

a. How do you get into the shot?

That is, does the shot come onto the screen by means of a FADE (the screen black at first… then the picture appearing, brighter and brighter) … a DISSOLVE (one picture gradually fading out while another fades in) … a WIPE (one picture pushing another off the screen in any one of a wild variety of ways, from straight vertical or horizontal to explosion), or what have you?

(If one shot follows another instantaneously, with no transition device specified, a CUT—the end of one piece of film simply pasted to the next—is taken for granted. Ordinarily, it isn’t mentioned in the script, unless perhaps used for shock effect.)

In our example, we FADE IN—all caps, note—because every shooting script so begins.

b. What are the conditions of work?

Three items are included here. All go on one line of the script, all are typed all caps, and all always go in the same order. They’re omitted if no change in conditions from the previous shot has taken place.

The three items, all essential information for the crew, are:

1. Interior (INT.) or exterior (EXT.).

2. Place (MACHINE SHOP, BEDROOM, STREET, RIVER BANK, etc.).

3. Time (DAY or NIGHT).

c. What’s the numerical designation?

Shots are numbered in sequence from a film’s beginning to its end. In production, before the action of a given shot starts, the shot itself is “slated.” That is, its number and other identifying data are chalked on a slate and filmed. This enables the director to avoid confusing the editor when he shoots out of sequence—as he almost certainly will, at one point or another.

d. What’s the image size and subject?

Both size and subject must be included. There’s no such thing as a “medium shot,” or whatever, in and of itself. But more of that later.

e. What’s the camera position?

This is the kind of thing you mention only if a particular position is essential to the point to be made—“high angle,” “low angle,” “shooting from back window,” etc. Fool around with such too much, or try to get fancy, and the director will both hate you and ignore your instructions.

f. What action is seen?

What—if anything—happens? Does an actor move? Does a machine function? And remember, the closeup of a knife on a table may be vital and highly dramatic, yet involve no action.

g. What sound is heard?

The thing to bear in mind here is that sound includes effects (motors roaring, hooves pounding, bells ringing) and music (which may or may not be designated according to type—BACKGROUND-PASTORAL, MYSTERIOSO, FANFARE, BACKGROUND-INDUSTRIAL, etc.) as well as narration and dialogue.

Any sound element you specify should be labeled, ALL CAPS, each time there’s a change—as from narrator to actor, actor to actor, sound effects to music, music to narrator/actor, etc.

h. How do you get out of the shot?

The issue here is precisely as in item a, above. Since no technical effect is mentioned, we assume that the shot closes with a cut.

So much for how you describe a shot. Beyond this, however, in item d, above, we made mention of image size. This is such an important—and potentially confusing—subject as to be worth particularly detailed treatment.

How large should a given object and/or action appear on the screen at a given time—and how do you label it in your script so it will come out within gunshot of the way you want it?

Your three basic image sizes are long shot, medium shot, and closeup. More often than not, scripts abbreviate these to LS, MS, and CU … or to such variations as ELS (extreme long shot), MLS (medium long shot), MCU (medium closeup), ECU (extreme closeup), and so on.

The key principle to bear in mind in using these various shots is relativism. That is, a long shot of a man may very well be a medium shot of the car he’s driving—and a closeup of the spotlight in the foreground.

In essence, each type of shot has its special function. You don’t use it just as a matter of whim, but because you have a particular job that needs doing.

Thus, a long shot is an orientation shot, an establishing shot. It relates a particular object and/or action to its surroundings, its background. In consequence, there’s no such thing as a “long shot,” per se … only “LS, Susie. Wearily, head down, rain hat pulled about her face, she plods up the walk.”

A medium shot is a subject shot… the object and/or action in and of itself, with a minimum of distracting background. “MS, Susie. She reaches the porch steps,” probably will include Susie, head to toe, but very little else save perhaps enough of the steps to make them identifiable.

A closeup is an emphasis shot—one which calls attention to the specific detail of the subject which makes the factual or emotional point you seek. Thus, in our imaginary sequence, we might very well follow the two shots above with “CU, Susie’s head. She raises it full face to camera. Her right eye is blackened, her cheek scraped and bruised. Tears stream down her face.”

And there you have it. No matter what story you seek to tell, what information you want to convey, you forever work with LS-MS-CU and their variations, even though for effect you choose to combine them in all sorts of outlandish orders.

Remember, however, that too great a jump—from ECU to ELS, for example—quite possibly may confuse your viewers; that too many closeups in a row may disorient your audience: frequent reestablishment of characters or whatever in relation to background is a must; and that your inspired dream of a shot that zooms in on Earth from outer space to a closeup of a gnat’s eyebrow may of necessity have to be tempered a bit in view of technical limitations.

Remember also that a given director or cameraman may not see a given image size as you do. Your “long shot” of a dining table may, in his eyes, be a “medium long shot”—or even a “medium shot” or “medium closeup.” Your only defense is clarity and precision of description every step of the way. If you want someone’s eyeball to fill the frame, say so!

And yes, there are other terms in use, almost unto infinity. A full shot takes in a person, head to toe; a knee shot chops him off at the knees; a waist shot, at the waist and so on. A close shot is a sloppy designation which indicates only that the camera is near the subject. In Britain, you’ll run into the BCU (big closeup)—we’d probably call it an ECU. But don’t worry about such; you’ll pick up the terms you really need as you go along. (I’ve listed some in Appendix D, the Terms You’ll Use section.)

3. Shooting script format.

The fact film shooting script ordinarily utilizes a two-column format, as per the sample in the following pages. Shot descriptions are in the left-hand column. Sound (a term which here includes dialogue, narration, music, and effects, remember) is on the right.

Set up with your paper’s left edge at zero in your typewriter. Assuming your machine has pica type (and industry practice says it should have), the following horizontal spacing will ordinarily be observed:

10—shot numbers

15—shot descriptions—40

30—transitions

45—sound descriptions—70

75—page numbers

Vertical spacing:

Page number—two spaces below top of page

First line—four spaces below page number

Conditions of work, shot descriptions—four spaces below preceding copy

Transitions—two spaces below preceding copy

Note that while directions, speeches, etc., are single spaced in the master scene script (see Chapter 13), the tendency in most fact film shooting scripts is to double space both shot descriptions and speeches. This will vary from shop to shop, however, so it’s always wise to try to check a sample.

Note also that sometimes the fact film will use master scene format.

Where capitalization is concerned, the following should be typed ALL CAPS:

Character names (often on first appearance only)

Conditions of work

Camera movement

Transitions

The pages which follow are designed to give you an idea of how a typical two-column fact film shooting script looks. Probably it spells things out more than is necessary. But the director can always adapt to his own taste and style, whereas too sparse a presentation may give him too little to work with.

BOOKS AFIELD

(Shooting Script)

TITLES COME ON OVER:

… and so, onward and upward, through 10 to 20 minutes of script.

But we can’t take time right now for all that. It’s more urgent that we move on to the next chapter and learn a bit about how to write narration.