Lessons from the Pros

There are a lot of ways to do things right.

That’s why this chapter includes excerpts from the work of seven different scriptwriters. The idea is to show you not The One True Path, but a variety of styles and techniques and approaches.

Since today’s film industry is in a constant state of flux, with emphasis strongly on the “different” slant, the “different” touch, all these case studies are new with this edition, with two exceptions. In those two instances (Charles A. Palmer’s The Gullies and Jack Turley’s Terror on the Fortieth Floor), I felt that handling was so uniquely instructive that it would be doing you a disservice to leave them out.

Circled numbers in the margins of the script excerpts/materials that follow refer to the numbered comments that follow each excerpt.

Where each of the five new scripts is concerned, I’ll comment on points illustrated as we go along, starting with:

NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET (original screenplay) by Wes Craven.

Originally from Cleveland and hooked on film from his teens, Wes Craven gave up college teaching (Freshman Writing, Modern Drama, Survey of Western Civilization) to try for a career in the field of motion pictures in New York. There, within a year and a half, he won the chance to write, direct, and edit a low-budget picture, Last House on the Left.

All of which makes it sound easier than it was, of course. Jobs that intervened ranged from grocery stock clerk to apprentice meat cutter, professional guitarist to illustrator to translator for a Lithuanian poet, apprentice cable splicer to nightwatchman to Manhattan cab driver. As a writer, he began with poetry, at 14; did a humorous column (Craven’s Raven’s) for his high school paper; edited (and later was fired from) his college’s literary magazine; and wrote (and failed to sell) a mass of fiction before hitting the cinematic jackpot.

The far-out has become his trademark. His credits include such titles as The Hills Have Eyes, Deadly Blessing, and Swamp Thing, plus a number of two-hour TV movies and some “Twilight Zones.” As this is written, he’s in Haiti, directing The Serpent and the Rainbow, a film based on a book by Harvard ethnobiologist Wade Davis. Craven says it represents a radical departure from his past work; it has an adult theme, looks at voodoo as a real religion, and has “a cast, literally, of thousands.”

Nightmare on Elm Street remains special, however. Its success is attested to by the fact that it has generated two sequels and a bulky paperback book.

The film focuses on supernatural horror, a recurring nightmare that comes to life. To make it all the more terrifying, it’s played against a totally down-to-earth setting.

Throughout, Craven demonstrates his awareness that the issue in any superior film is feeling, emotion. His ability to devise incidents and pick significant details to communicate the feelings he seeks to rouse in his chosen audience is outstanding, as is the way he manipulates the ebb and flow of tension to the film’s nerve-shattering climax.

an

original

filmscript

by

Wes Craven

Registered

WGA 1984

(c) 1984 New Line Productions, Inc.

The numbered paragraphs that follow refer to the marginal numbers in the script excerpts.

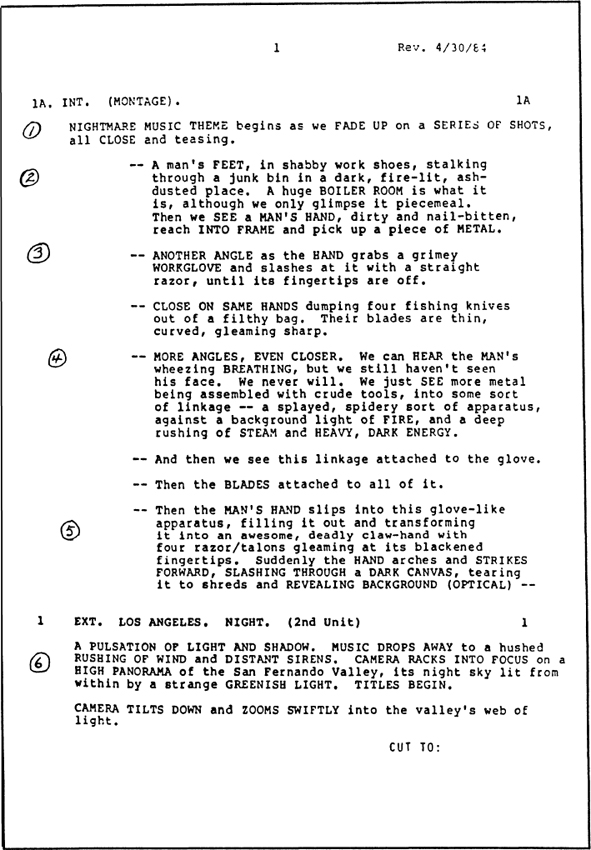

1. Actions speak louder than words, a point well demonstrated in this montage. The pictures tell the story. Further, they’re pictures chosen to capture emotion … establish a menace-pulsing mood, with music to help create and build the feeling.

2. Note how Craven heightens tension through his selection, arrangement, and description of shots. We don’t see the man … merely his feet, stalking through a fragmented and hence sinister place. Then, we see his hand—a “dirty and nail-bitten” hand as it performs a simple act … unexplained but, we assume, foreshadowing something fearsome.

3. Still no explanation, but the razor and the slashing project further menace.

4. More mysterious action, with tension heightened by the faceless man’s breathing, the steam sounds, the background firelight.

5. Climax of the buildup: We see the pattern, the purpose, behind the earlier shots. A horrifying weapon has been created; its potential for destruction revealed.

6. Title background. Setting’s established … then menace.

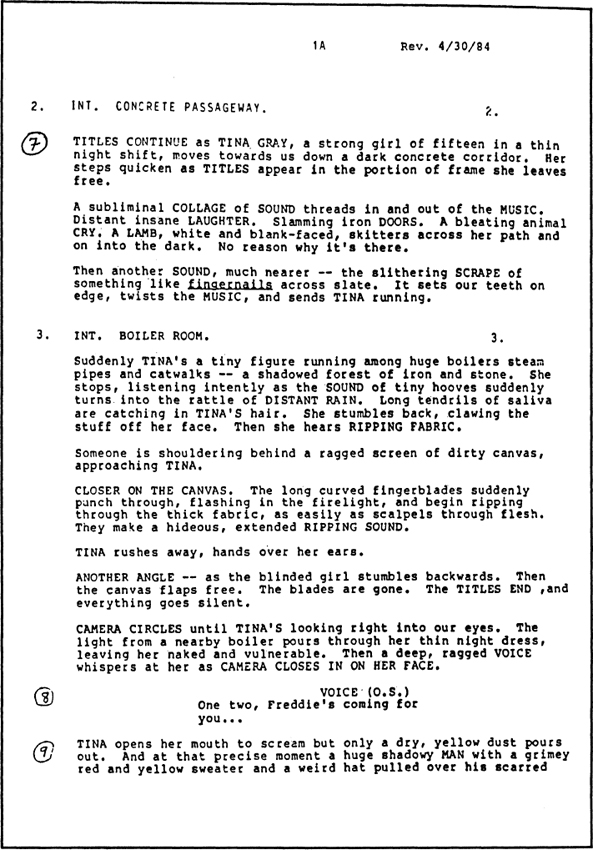

7. We meet a victim-to-be, Tina … move into footage designed to establish that this is a nightmare … her nightmare, the nightmare from which the film takes its title.

Why start with Tina, rather than our heroine, Nancy? Because her doom foreshadows Nancy’s potential fate; gives viewers something to fear will happen.

“The device of killing Tina was quite premeditated,” Craven observes. “Investing the audience’s confidence in the apparently stronger of the two girls, I then destroyed that confidence along with Tina. It left the audience to identify with what it could only assume upon initial evidence was the weaker woman. I like that psychic situation—the discovery of greater strength out of what first appears to be greater weakness.”

8. At last, a voice… introducing us to the doggerel chant that’s to constitute our theme.

9. Our villain—a “shadowy” figure, in keeping with the dream atmosphere, but tagged with “red and yellow sweater,” “weird hat,” and “scarred face” for easy identification later.

* * *

Note how this opening has clearly set up genre, mood, and color, yet has done so with minimum footage and without dialogue.

* * *

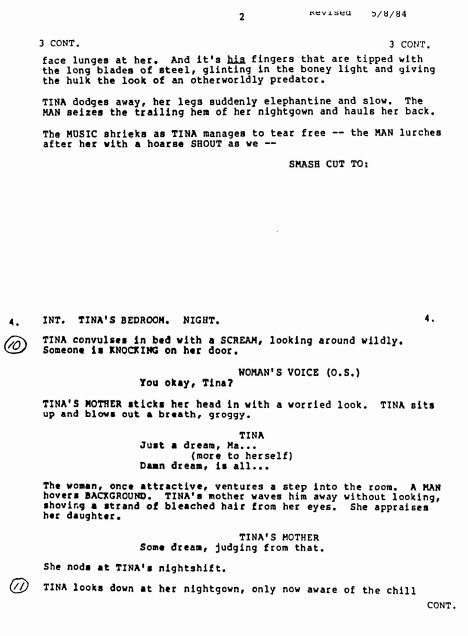

10. Reality at last. The opening’s all just a dream.

11. Well, maybe.

12. The cross brings the intensity of Tina’s fear into focus.

13. Our running theme: the jump-rope song, foreshadowing the horror to come.

14. Which reality shall Tina—and we—believe? Craven has set up a contradiction that’s a cinch to lock in any horror film audience for the duration of the picture.

15. Enter our heroine, Nancy … introduced visually, sans a lot of verbal exposition.

16. Our theme and threat spelled out: … never sleep again …

* * *

17. The long jump from Nightmare’s page 3 to page 86 sees Craven develop his characters as warmly human young people—individuals we can understand and believe in. Also, there’s a lowering of immediate tension from time to time, plus the introduction of more information on the menace.

These are important issues in the building of any picture. Stick-figure story people just aren’t good enough. Viewers need to see characters in such circumstances that they can come to care about them, worry as to what’s going to happen to them.

They need periodic relief from high-voltage tension, too. If they don’t get it, sheer nervous strain may take over and lead them to burst out laughing at the most suspenseful moments.

So it goes with Nightmare: an alternation of peaks and valleys that builds tension higher and higher by the very fact that periodic relief is provided.

Then, at last, page 86, the pinnacle of a particularly harrowing scene, and heroine’s reaction to the horror. And that, too, is important, for it’s not enough for a heroine, jeopardized, to palpitate in panic. Your audience wants to see her rise to meet the challenge.

Here, Craven lets Nancy realize that she’s on her own; that she’s going to have to fight her own battle if she’s to survive. And since that’s the case, he gives her intelligence, nerve, a plan of action … then has her do, not just talk; counterpunch as well as quiver.

18. Focus on audience psychology … the teenage conviction that adults don’t really pay attention to them or take them seriously. In line with this attitude, viewers take it for granted that Lt. Thompson will give no serious heed to Nancy’s pleas. Thus the scene extends time and the anticipation/fear of what’s to come, and tension builds even higher.

19. Setting the stopwatch is Step 1 in Nancy’s plan of attack. It’s specific action, and everyone can understand it. But we don’t know what she plans to do, what Step 2 is to be, so we’re glued to the screen, panting to find out.

20. We still don’t know what’s ahead. But clearly, something is, so we’ll keep watching.

21. More unexplained action to intrigue us. It all adds up to some kind of booby-trap designed to trap Fred Krueger. But how?

22. Craven inserts a brief scene designed to isolate Nancy further. Clearly, her mother has no potential for helping her.

23. A young girl, challenging the powers of darkness with her own courage and a child’s prayer. It builds on every level.

Craven says: “This scene completes one of the more subtle but powerful transformations in Nancy’s character—the total reversal of roles between her and her parents in a time of utter crisis. I believe this is one of the most profound passages in life—one we all must some day do. Nancy, as Everyman, does it at the beginning of her third act, much as we all do personally within the ‘movie’ of our own life. In the next scene, with her child’s prayer, she includes her most precious, creative self—the child. Then she takes action as the full adult—child, parent and Present Self unified in one powerful whole—utterly awake, terrified by this unvarnished awareness, but in possession of will—and acting in free autonomy to survive and prevail.”

24. The truth dawns on us. Despite all peril, Nancy is going to play bait for Krueger by letting herself go to sleep.

* * *

25. From page 92 to page 104 Craven builds through scene after scene of violent, blood-chilling action, pulsing with horror as Nancy meets and defeats her unearthly foe—a brilliant example of how a skilled craftsman manipulates time and circumstance to create a climax.

Then, at last, on page 104, resolution—we think. The end of nightmare and tension, dissolving into day’s release and light, birds singing, children at play.

26. Full circle back to reality. The menace faded to memory, the dead risen. Only the strange fog strikes a discordant note … hints that not everything is quite as it seems.

27. And then—Fred Krueger. Total switch, total reversal, total shock.

28. The slam of the car-top, the snap of the trap. The final twist, to bring adrenalin surging.

29. We FADE OUT on a reiterated note, our jump-song/horror theme.

* * *

There’s more to Nightmare on Elm Street, of course. A lot more. But by now the pattern should be clear. From beginning to end, Craven works with threat, menace … the fear that something will or won’t happen. At no point does he allow his audience to truly relax or get off the hook.

Further, ending as he does, we conclude with a blaze of new peril; and, in so doing, leave viewers something to shiver over and talk about after the show. It’s an open ending, the kind designed to bring audiences back to the theater for yet another round.

Was Craven’s approach successful? Nightmare’s box-office jackpot and the fact that more than two sequels already have followed tell the story.

SECRETS OF THE TITANIC (original film-on-tape script), by Nicolas Noxon.

On the night of April 14–15, 1912, the “unsinkable” British liner Titanic, largest ship afloat, struck an iceberg on her maiden voyage and went down with a loss of more than 1,500 lives. It was the greatest maritime disaster of all time.

Seventy-three years later, in the North Atlantic 350 miles southeast of Newfoundland, a deep-sea expedition sponsored jointly by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and the U.S. Navy reached and explored the sunken Titanic, 2½ miles down.

The National Geographic Society felt that a film should be made to bring the full impact of his well-nigh incredible feat to the public. Preparation of the film’s script was assigned to Nicolas Noxon. He was also named the producer.

London born, Canadian reared, U.S. educated and a citizen here since the 1950s, Noxon was a natural selection. Enamored of film from childhood, at Antioch College he majored in “what in those days was called Mass Communications. That meant drama and theater arts and sociology.” His first student film was a pantomime of about 15 minutes called Masquerade.

Preferring “true” stories to fictional ones from the beginning, his first major post-college film was Time of Migration, a documentary about a herring “run” in New England. Since then, films produced and/or written by him have won virtually every award in American television, as well as prizes at many film festivals. His work for The National Geographic Society includes writing and producing The Sharks, the highest rated program of any type ever broadcast on PBS. Other Noxon productions have been in association with David L. Wolper, Columbia Pictures, MGM, and Sports Illustrated.

Today, after 25 years in film, Noxon sees himself as equally writer and producer; to a lesser degree, as a director. His work in Secrets is particularly notable as an example of his outstanding ability to find the tension and drama in factual and technical material. Here, history comes alive in his script as he captures, builds, and communicates the interest and excitement that went with the location and exploration of the Titanic.

The pages shown here are from his final script.

Excerpts from Secrets of the Titanic used with permission of Nicolas Noxon and the National Geographic Society. All rights reserved.

1. The National Geographic Society follows the traditional two-column informational film format in its productions: video on the left, audio on the right.

2. The video side here, what the audience is to see, clearly is “pickup footage,” documentary coverage chosen from various film archives.

3. The narration track is packed—infinitely more wordy than would be the case in the average picture. Yet as Noxon points out later, the information given is essential to understanding of the film’s subject.

Note, too, how Noxon translates generalities/abstractions into concrete terms that viewers can understand: “3,000 men”, working “more than two years”, “a mountain of steel”, a hull that would span “four city blocks”, engines “the size of a three story house”.

* * *

Jumping ahead to the present day, and page 22 of Noxon’s script, we’re introduced to the first attempt to reach the Titanic by the Woods Hole/U.S. Navy expedition:

4. An interest-focused device: the hint that something may go wrong almost automatically grips viewer attention.

5. Curiosity satisfied: a look at the submarine’s interior.

6. On the one hand, information about Alvin. On the other, a testimonial as the submarine’s merit in terms of past accomplishments.

7. Intensely aware of how much narration he’s packed into this script, Noxon takes advantage of an opportunity to add life by introducing a fragment of lip-sync speech.

8. Lip-sync has its limitations too, however. Often, as in this bit, narration conveys information more concisely than can speech.

9. Virtually an entire page of lip-sync builds a sense of “experiencing” (and tension) in the audience. Lines like “I can’t believe they can only see 20–30 feet” and “we’re running low on power” build viewer excitement higher and higher.

10. Back to narration, covering a decision and 2½ hours of tedium in 24 words.

11. Confidence, competence, indomitability, served up in a single speech by an authority figure.

* * *

On to page 39:

12. The Titanic located and the Alvin repaired, exploration of the sunken ship continues. First the exterior is surveyed; then, the interior probed. Thousands of pictures are taken, a detailed map of the Titanic’s remains developed. A model of the wreck site makes the situation underwater more easily understandable. Ingenuity in devising such approaches is tremendously important for a writer.

13. Here Noxon uses animation and footage from old feature films to take us into the past … the night the Titanic sank.

14. Still photos help to build a sense of reality. Others follow, plus underwater footage and more animation.

* * *

The script’s final pages—45, 46, 47:

15. Narration, visuals, and human interest build to the conclusion.

16. Noxon wraps up the Titanic’s story. But he leaves it to Dr. Ballard, as the expedition’s leader, to voice the great ship’s epitaph,

17. A shot of the plaque provides a lead-in to Ballard’s voice-over closing words. It’s a touch that helps to avoid audience confusion.

18. A film like The Secrets of the Titanic develops a spirit all its own, born of the insights the writer develops into his subject and his feeling for it. Noxon captures that feeling/insight when, concluding, he links this final photo of the Titanic with underwater footage.

19. It’s in total keeping, too, with Ballard’s words … a memorial that acknowledges arrogance as a form of fate, laid to rest now in the quiet of the ocean’s depths.

* * *

NOXON ANSWERS SOME QUESTIONS

Do you work entirely free-lance?

Noxon: I’m free-lance, but I do projects that tend to be long-range. This thing I’m working on now will be at least a year.

What’s the project?

Noxon: It’s another for the National Geographic Society—a film for its centennial. I’m in charge as far as the script is concerned.

How did you get the Titanic assignment?

Noxon: I guess I got chosen because I’d done a lot of underwater subjects before. Also, I was acceptable both to Ballard (Dr. Robert Ballard, the geologist and undersea explorer who headed the expeditions to locate and explore the Titanic) and to the Geographic Society.

How long did the Titanic script take you?

Noxon: Beginning to end, the whole Titanic production took about four months. The actual narration writing took two-and-a-half weeks.

What made it go so fast?

Noxon: The immense advantage I had was actually going along on the expedition. It gave me unpressured time to think and plan. I did most of my Titanic reading on the ship, right over the wreck. It was a crash course. If the script’s good, in part it’s because it had very good preparation.

Clearly, your script isn’t a complete shot list.

Noxon: It couldn’t be. On a job like this, you can’t predict precisely what will happen. Sometimes things you plan just don’t work out. Others, you run into details you didn’t anticipate that add interest. You’d be a fool not to take advantage of them. So your best bet is to hang loose, play by ear, move with the flow of developing action.

But the script was written before the fact? Where the live action of the expedition was concerned, you pre-planned the line of development insofar as possible? You didn’t just write to the footage after the fact?

Noxon: On Titanic and most of my films, no narration is written until the editing is complete. Until then the written evolution of the film is as follows:

Sales presentation or treatment (if necessary)

Shooting outline (often revised during shooting)

Editing outline (also often revised)

“Scratch” rough narration for approval screenings (if required)

Final narration—written to fit final picture

To explain the process as briefly as possible, you plan everything you can and change the plan to accommodate reality. But in the end pictures dominate words and the final narration is written to support the visual story.

Do you consider this film a compilation job: a gathering together of bits and pieces from all sorts of sources?

Noxon: Yes and no. Some of the background stuff was pickup, of course. But the bulk of it—the preparations for the expedition, the expedition itself—we shot ourselves.

In other words, you were actually able to prescribe the footage that you wanted.

Noxon: To a degree. I was working in cooperation with an English crew, so both their requirements and ours had to be satisfied. A certain amount of negotiation was involved. But I did get a good bit that I wouldn’t have had otherwise.

Would you class Secrets of the Titanic as primarily film, or primarily videotape, or what? Or, if you see it as a mix, what do you consider to be the advantages of each method in this particular situation?

Noxon: Titanic is a “film on tape.” We shot tape exactly as we would have film and the editing process was very similar. In this context the big advantage of tape is the ease with which you can shoot great amounts of footage. That’s the disadvantage too. You get careless and lazy.

Were you in on the editing?

Noxon: Yes, I directed the editing. do that in almost every case.

For what reason?

Noxon: You know what you’re thinking, how you’ve conceived the film. Someone else is bound to see it differently. More often than not, they’ll miss the points you want to make. When that happens—well, it can be pretty hard to come in at the end.

It struck me that as scripts go, this one is short in terms of the number of pages.

Noxon: Yes, but I think anyone in the business is going to notice that it’s also very heavily narrated. It’s by far the longest script I’ve ever written for an hour; it has far more words. I belong to the school that less is more. I try to write as little as possible. I get very suspicious of my own motives if anything is even slightly long. I wonder if I’m falling in love with my own words.

Noxon: This script is so enormous I doubted my own sanity. I went back over it and back over it and back over it. I gave every line the acid test of necessity. And I found that I needed it all. I mean, it worked very well, even though it’s very, very wordy. I don’t think the story could be told as well in many fewer words, but it still worried me.

Why do you think it ran so long? Can you pin down any general reason?

Noxon: Well, I think that sometimes people need to know more than they need to sit and look at things that otherwise are meaningless. To understand this film, people needed background, and words, narration, were the only way to give it to them.

Putting aside the script for a moment … the meld of video and music in Secrets struck me as tremendously effective. Did you—as writer; as producer—play a major role in its selection?

Noxon: I worked with the composer and decided when and where music was needed. This close involvement with every phase of production is my “method.” Every writer (at least in documentary) should strive for this if only to gain experience and respect for the different arts and crafts involved. This is how and why many writers become producers. They discover that merely writing a film doesn’t guarantee its quality. Seeking better control, they end up as producers. There are few “pure” writers in documentary. The authorship is too much a part of the process of production.

The film was an enormous success, wasn’t it?

Noxon: It certainly was. To me, though, what’s even more interesting is that it’s been an equally big success in home video. In fact, it’s the best selling non-fiction video to date. At one point it was number five in video cassette sales. Which makes it a breakthrough for all of us who do this kind of work. I knew that it would get on television, but at the time I was working on it, I didn’t know when, and I wasn’t sure how the commercial breaks would be arranged. But I was face to face with my television editing console every day, so I found myself thinking about it in terms of how I’d react and what I’d want to know if I was watching it in my living room. So that became my guideline; I edited it in terms of that.

Titanic continues to amaze me with its success. When aired by Turner Broadcasting it posted the highest rating ever for a basic (non-pay) cable program. It’s very pleasing to have a film run away from the competition as this one has. Now the question is, “Can we do it again?”

THE GULLIES (fact film proposal), by Charles A. Palmer.

THE GULLIES (shooting script, Episode B), by Charles A. Palmer and Audrey Kaczenski.

Once upon a time there was a highly successful New England businessman named Charles A. (“Cap”) Palmer. Later he became a highly successful film writer. Then, tiring of the major studio routine, he abandoned it in order to set up his own corporation to produce business films for such firms as Kaiser Aluminum, Western Electric, International Harvester, and Hilton Hotels, among others.

Two-hundred-fifty pictures and innumerable awards later, Palmer continues today as executive producer of Parthenon Pictures, the firm he founded.

He also continues to develop and script films, with The Gullies an intriguing example of how to promote and package a fact piece.

The proposal

How do you sell a concept? It’s a fine art, certainly, and each picture demands its own approach. But this excerpt from Palmer’s handling of his Gullies proposal is a good example of a highly skilled pro in action.

Excerpts from The Gullies used with permission of Charles A. Palmer and Parthenon Pictures.

1. Fact films come in all shapes and sizes. Witness that this proposal is concerned with a series of five five-minute pictures.

2. Palmer says he’s simply a good explainer, not a salesman. Here he explains why he’s giving his explanation.

3. The prevailing situation, briefly outlined.

4. Why Palmer feels the traditional approach isn’t the best, in view of said prevailing situation. Observe that this is presented in terms of purpose and audience.

5. Having shot down the traditional approach in flames, Palmer now introduces his first sales—pardon me; explanation—point: the virtue of repetition.

6. Point 2: an attack on the normal-length picture as a solution to the client’s problem.

7. Now, the Palmer solution: a series of mini-pictures, each devoted to one technique by which consumers are conned.

8. Next: What approach to take in order to catch and hold an audience.

… and so it goes, point after point. The final product adds up to a pleasant, informal, low-key presentation.

A proposal, outline, or treatment can, to a degree, stay general. A shooting script, in contrast, must spell out what happens in such detail that a production crew can capture the desired action effectively on film, as witness these excerpts.

1. Like most fact film producers, Parthenon favors the two-column format—visuals to the left, sound to the right.

2. Shooting instructions are abbreviated to a sort of shorthand. In some instances orders are extremely specific (“SHOOT 15 times @ 5’ “), but often they’re looser and less rigid than in many shops. Which same is a good example of why it makes sense to ask to see a sample script when you tackle a job for a company with whose format style you’re not familiar.

3. This picture and the others in the series are basically brief fact films. But because they’re also designed for TV use wherever possible, as per the proposal, they’re set up in TV series style, with fast establishment of characters, setting, and general circumstance.

4. Ordinarily the proliferation of “G” names here (the Gus, Gracie, Gil, Gloria, etc., thing) would be a no-no. But The Gullies’ slant is comedic, so the matching initials add rather than detract from the effect.

5. Voice-over narration cuts costs and simplifies shooting. Note that only one narrator is used, although many passages (5a and 5b, for example) simulate speech by individual actors as they mime their roles. It’s one of the many devices by which life and interest can be added to a narrated film.

6. This is the kind of thing that in many scripts would be labeled “INSERT.”

7. Frequent use of exaggeration and incongruity help give the narration/dialogue a comedic tone to help build the overall style set for the film.

8. The basic “bait and switch” angle—a low-price come-on, to bring in customers who then will be coaxed and cajoled into buying something more expensive—of the episode is established.

Now we move ahead to page 10: the episode’s climax and payoff.

9. By using an art background—that is, one painted on a flat or the like—instead of dressing and lighting an elaborate set or shooting on location, costs are reduced.

10. A time lapse, and a DISSOLVE to cover it.

11. A final twist, a final laugh: After all the furore, Gus still ends up with the music he loathes.

12. Well-chosen fast cuts (that is, a montage) from what has gone before is a useful device for visually summarizing the points previously made.

13. Meanwhile, our narrator hammers home the message.

PLATOON (original story and screenplay), by Oliver Stone

Himself 15 months in Vietnam with the 25th Infantry Division, complete with Bronze Star for bravery and multiple Purple Hearts, Oliver Stone created Platoon as a labor of personal passion, a blood-drenched morality tale that arouses fierce emotion and clings in memory like a jungle leech. Surely one of the most controversial films of recent years, it focuses on the experiences in the field of a young soldier, a “cherry,” from his arrival at a base camp airstrip through his survival of four patrols to his shot-up, pain-racked evacuation by helicopter at the end.

Born in 1946, Stone grew up in Connecticut and New York City. He was tuned in to writing from childhood, but otherwise tended to a loose-ends style of life—traveling, dropping in and out of college, writing a novel that failed to sell.

Then, Vietnam. Discharged and returning to the United States in 1968, he wrote Platoon in 1976. The years between saw him attend New York University on the G.I. Bill, studying film under famed director Martin Scorsese. Graduated in 1971, he wrote and/or directed a spate of minor films, largely horror, later connecting more solidly with such scripts as Midnight Express (which won him an Academy Award in 1979), Scarface, and Salvador.

Platoon remained words on paper only, however. Although it was shopped around to virtually everyone in Hollywood, no one was willing to gamble on its commercial potential for nearly 10 years, until 1986.

Once the picture was released, reaction flipped over. Audiences and reviewers alike came to appreciate the devastating realism Stone brought to his work, and the way he interwove explosive action with aching lulls and anticipatory tension. Even viewers who argued that much of the picture he painted was distorted acknowledged his skill at capturing character and the manner in which he suffused the whole panorama of war in Vietnam with a strange, bitter lyricism.

The end result was a film that packed theaters, won the cover and featured treatment in Time, and claimed Academy Awards for both script and Best Picture.

Excerpts from Platoon, © 1976 by Oliver Stone, used with permission of Oliver Stone and Ixtlan, Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Note that the film’s title was The Platoon in Stone’s script, but the picture was released as Platoon. Clearly, someone somewhere along the line felt that the title carried more impact without the article.

2. The script was totally Stone’s work. He claimed credit for both story and screenplay.

3. The 10-year lapse between script and Ixtlan’s production is brought into focus by the two dates.

Page 1 of the script:

4. Irony and bitterness in a Biblical quotation keynote the opening shot.

5. New recruits come on center stage. Their condition and status is established visually, without words, by their haircuts and new fatigues.

6. Our central character, Chris Taylor, is introduced, his importance made clear via the “tight closeup,” an emphasis shot. Stone also makes it obvious that he’s out to “sell” a mood, a feeling, by his line, “eyes searching for the truth”—“eyes searching” can be photographed; “for the truth” can’t. It’s the kind of device Stone uses frequently in this script.

7. The tension-building shock of contrast: life, personified in the recruits, played against the shadow of death carried by the body bags and flies.

8. Veterans: more contrast, more tension. These are survivors. Their happiness sharpens the implication of the danger ahead for the recruits.

Page 15:

Too often, critics of Platoon have viewed the picture in terms of blood and violence, focusing on dope, rape, blood lust, degradation, and the murder of soldier by soldier. Its philosophical elements and ethical concerns have been lost in its rush of action.

Actually, there’s more than a little thoughtful dialogue sifted through the rage and turmoil. Character development is strong and solid, as witness Stone’s work on this page of script.

9. Chris’s letter to his grandma … another of Stone’s devices for introducing ideas not easily set forth or interpreted in pictures. Here, we gain insight into Chris’s goals and feelings, his reactions to his previous life.

Also worthy of note is the fact that Chris’s letter is to his grandmother. In having his central character write to her, rather than to his parents, Stone has made it possible for him to express his deepest feelings more honestly and candidly, with less restraint and inhibition, than he might otherwise.

10. Pride and duty, we see here, are prime components of Chris’s character. He has a heritage he wants to live up to.

11. Stone’s Vietnam-shaped attitudes and insights where his fellow-grunts are concerned are seen here through Chris’s eyes.

12. Clearly, the soldiers who serve with him have helped to shape him. He sees through the ego-armor war has forced them to wear to hide their doubts and fears and inadequacies. And out of the understanding he’s gained he’s found new values for himself … a humility that acknowledges that what you want often is what you’re afraid you haven’t got.

Page 74:

13. Moving through the jungle, Chris’s squad comes under fire—an ambush. One of those hit is Lerner, the point man. He’s isolated, cut off from the others. Chris, coming forward, sees him.

The page of battle action that follows is developed in master scenes. Stone describes what’s happening, what the audience is to see and hear, leaving it to the director (Stone himself in this case, as it worked out) to break it down into shots. It’s a veteran’s battlefield experience made visual, translated into photographable action-images, the kind of thing Stone does ever so well.

14. Stone establishes danger—and with it, heightened audience tension …

15. … then releases that tension (at least temporarily) with Chris’s successful throw of the grenade.

Page 122; the script’s final page:

16. Rhah, a strongly tagged secondary character, here emerges as a climactic symbol both of defiance and of the eternal conflict of love versus hate which Stone has built.

17. This voice-over monologue by Chris is a good example of why Platoon is as much philosophy and morality play as action film. When he says that Vietnam’s survivors have an obligation “to try with what’s left of our lives to find a goodness and meaning to this life …” duty and rectitude and principle are put into words.

18. The wrap-up. Clips of the film’s various characters sum up Platoon’s message of the oneness and differences of all men as brought into sharp silhouette by war.

Especially to the point is the fact that we conclude on Barnes and Elias, for in essence the picture hinges on them. Both sergeants, both superior soldiers, each in his own way personifies the clash between evil and good that lies at the heart of Platoon: Barnes, who earlier has been described by Rhah as “That man is mean, man, red in his soul … Barnes comes from hell … He’s roaming these jungles looking for litde yellow devils to kill”; and Elias, the handsome, graceful Indian three years in Nam who thinks killing’s cheap, “the cheapest thing I know,” and who describes death as “like a giant garbage can,” and hopes that if he’s reincarnated he’ll come back “as wind or fire—or a deer.”

Stone’s message could hardly be clearer.

TERROR ON THE FORTIETH FLOOR (outline), by Jack Turley.

TERROR ON THE FORTIETH FLOOR (sequence cards), by Jack Turley.

TERROR ON THE FORTIETH FLOOR (treatment/step outline), by Jack Turley.

TERROR ON THE FORTIETH FLOOR (elaborating notes), by Jack Turley.

TERROR ON THE FORTIETH FLOOR (teleplay), by Jack Turley.

Jack Turley prepared for a scriptwriting career with TV production experience in such places as Oklahoma City and Albuquerque, then moved to Los Angeles and enrolled in TV writing courses at UCLA. His first sale was to Route 66—a collaboration with his instructor, Milton Gelmer. Now, with 20 years’ experience behind him, he is turning more and more to the movie-of-the-week type of thing. Pray for the Wildcats, Hurricane, and The Day the Earth Moved are among his recent credits.

Terror on the Fortieth Floor, airing as a two-hour, seven-act show, kicked off NBC’s 1974 season. It also has been released in Europe as a theatrical film, as well as rerun in the U.S.

Turley’s handling of Terror offers excellent insights into the entire process of script development. Here we see how it was built step by step from a story by Turley and Ed Montagne.

Excerpts from Terror on the Fortieth Floor used with permission of Jack Turley.

1. Titles do tend to change. The Only Way Is Down, Turley’s choice, stayed with his script most of the way.

2. Turley’s presentation of his materials is an interesting variation on the traditional outline. His use of subheaded groupings of data (“THE PHYSICAL ELEMENTS,” “THE DISASTER,” “THE PEOPLE,” “THE OVERALL STORY APPROACH”) breaks a complex mass down into easily grasped components.

3. “THE PHYSICAL ELEMENTS” is really a statement of the background of the action, the circumstances under which the story takes place.

4. In choosing Christmas as the time for the action, Turley establishes a strong joy/tragedy contrast. Similarly, the disaster stands out starkly against the background of office party revelry.

5. Here Turley establishes the plausibility and logic of his situation, anticipating and answering possible viewer questions even before they arise.

6. More holes are plugged, the sense of jeopardy intensified.

7. It’s easy to lose readers—even experienced script-readers—in a mass of details. By simplifying his people to the label level, Turley makes them instantly understandable stick figures.

8. The image of each person established via label, Turley now elaborates them into believable human beings, giving them attributes and backgrounds as required.

Skipping ahead to page 11 …

9. “THE OVER-ALL STORY APPROACH” reveals the broad outlines of Turley’s plan of attack in thumbnail form.

10. No one exists in a vacuum. Here characters are revealed in greater depth by showing their interrelationships with others beyond the scene of the fire.

11. Plot angles, tension factors, are developed.

12. The mechanics of resolution. No producer wants to take chances on a writer writing himself into a corner.

13. Character’s great, but viewers like excitement too.

14. Tension released; physical problems and peril resolved. But a good character has a future as well as a past, and an effective denouement must at least foreshadow it.

15. Tone and residual impression are important. Turley sets forth his own views on the subject.

The sequence cards

A few of Turley’s sequence cards: a writer’s notes to himself on how to develop his play. These all are from Act 1.

Turley prepares neither a treatment nor a step outline as such, preferring instead this combination form that includes elements of each.

1. Presentation is, in effect, by sequences. Each is labeled as to location and, if necessary, by DAY/NIGHT or the like.

2. Handling in this sequence ranges from impressionism to “telling” summary.

3. Key plot factors are included, even though not yet fully developed.

4. Characters also are introduced, within the same general framework in which they’ll come on in the final script. Now, too, the characters have names as well as traits and backgrounds.

The elaborating notes

An actual screenplay or teleplay requires infinitely more detail than the summarized versions that go before. Turley works these out on yellow legal pads.

1. Credits are important to every scriptwriter. Here, Turley gets a joint story credit, plus solo teleplay credit. (And though the script terms this a teleplay, remember that the finished picture was released as a feature film in Europe—a clear indication of how much the two media tend to overlap today.)

2. Check the first sequence of Turley’s treatment/step outline, above, against these three paragraphs. Time and place now are established in terms of specific images. Thus, the Santa Claus in effect says Christmas; the bit with the watch and kettle sets the time. The camera’s upward sweep tells us where the party’s taking place.

3. Mood and general situation are established swiftly. Turley begins to zero in on his story people.

A jump ahead to page 41 now:

4. Action here is at the party.

5. Now, a cut to parallel action: strong contrast, extreme jeopardy.

6. A different scene; more parallel action. Turley brings in necessary exposition via the dialogue between the TV newsman and Captain Thomas.

7. An important plot line here. Captain Thomas’s assumption that the top floors are deserted can’t help but heighten viewer suspense as jeopardy to the trapped party leaps higher.

8. Back to the party again, but centering on Ginger, one individual, with a consequent concentration of attention.

9. Suspense is heightened and attention focused even more sharply by shooting Ginger’s panic reaction before revealing its cause … an excellent technique, but dangerous unless motivation not only follows immediately, but is instantly understandable to viewers.

10. Now, the payoff to Ginger’s reaction—not to mention the jeopardy pinpointed in 5, above, and Captain Thomas’s assumption (in 7) that the building’s upper floors are deserted. A tremendous visual cliffhanger for an Act 2 curtain, it’s intensified even more by the music “sting”—a sudden, jarring musical note struck for emphasis, like an exclamation point at the end of a sentence.

11. The pickup after the act break: swift, wordless reestablishment of peril.

12. Back to the fortieth floor. Our characters react characteristically to the crisis—Overland coolly, Ginger naively, Darlene in terms that, in effect, make possessions worth more than life itself. All of which is, of course, highly important storywise—for our story concerns not just a fire, but the reactions of people with whom viewers are emotionally involved to the character-testing jeopardy the fire represents.

13. A suspense-heightening return to parallel action.

Again we jump forward … this time to the final scenes of the picture’s resolution.

14. The fate of one character after another is resolved. And since we see this through Darlene’s eyes, she becomes increasingly the focal point of viewer interest.

15. Christmas morning has arrived. The night of terror is over.

16. There’s still no happiness for Darlene, or for Kelly. But Darlene has strength. She’s still in there fighting. It’s the kind of thing that makes a character admirable to viewers.

17. Kelly, too, gains sympathy, as we discover he has a conscience. And since Darlene understands, at least there’s hope for them, even if not instant happiness. Which is fine, for a quick save would have come through as both corny and unbelievable.

18. There’s a larger world beyond the problems of Turley’s story people, however. Now, it takes over, with Harper clarifying the situation where the fire is concerned.

19. Harper voices a feeling which most viewers will share.

20. A new day … peace, and a return to reality for viewers, in contrast to the night’s fear and tension.

INTERNAL CRIME PREVENTION (informational video script), by Benjamin S. Walker.

Scriptwriters come from all kinds of backgrounds and operate on all sorts of levels.

Benjamin S. Walker offers a good case in point. Born in Omaha, Nebraska, and brought to Washington, D.C., at the age of 11, he won a scholarship to Auburn and earned a degree in chemistry as a Navy ROTC student.

He wound up not caring much for chemistry, however—“I always was a reader and a writer,” he says. After paying for his education with an obligatory three years of Navy service, he took a job as a technical writer with RCA, later worked for other firms, and ended up in 1960 with a newly formed film group at Johns Hopkins University.

Today, he’s supervisor for production with Johns Hopkins’ audiovisual team, successor to the film unit, turning out slide shows, films, and (mostly) television. As such, he estimates he’s written more than 300 scripts for Johns Hopkins.

That’s only part of the story, however. For 20 years Walker also has free-lanced scripts (at least 200 of them) for other organizations: a total of more than 500 writing jobs completed, on topics ranging from medicine to computers to satellites to human interest to recruitment to training—“and just about anything else you want to name.”

Most of Walker’s outside chores are on assignment. The rest he wins on bid. His free-lance client list includes the U.S. Postal Service, for whom he did Internal Crime Prevention.

It’s a script particularly worth noting for the manner in which it combines interest with information, interweaving factual content—that is, the client message—with a presentation designed to catch and hold its target audience. Yet it does this in a straightforward, down-to-earth fashion in keeping with its topic, with none of the hype or hoke that too often is injected into informational films.

Excerpts of Internal Crime Prevention used with permission of Benjamin S. Walker and the U.S. Postal Service. All rights reserved.

1. Setting/situation and a degree of interest are established from the start by the background against which the titles are superimposed. And the rock music indicates that handling isn’t likely to be overly pontifical.

2. A wordless focusing of attention on the kind of people who are going to make up our cast.

3. The producer’s warned of a potential casting problem: the narrator’s going to do double duty—acting, as well as reading commentary.

4. Narration here is voice-over. Which both simplifies the job and cuts costs—by and large, no location sound man will be needed in this show, save where there’s lip-sync dialogue.

5. The narration itself uses contrast—“But, are they?”—to raise the tape’s lead-in question fast.

6. Walker flips our narrator from disembodied voice to living person—an authority figure, identifiable by badge and doing his job as an observer.

7. The motivational message, delivered lip-sync for impact… narrowing down at the end to the immediate issue.

8. We begin a sequence in which both major types of thieves and techniques of theft are established, via zeroing in on individuals.

9. This “capturing the moment” continues as Walker picks specific action, significant behavior, to make his points.

10. Interweaving of lip-sync and voice-over narration continues, and we meet a second authority figure, the local postmaster, a key target of this film.

* * *

11. Skipping forward in our Internal Crime Prevention script, we again encounter Joyce, the window clerk whom we first met on page 3. But where there we caught her in the briefest of capsules, here we observe her theft technique in more detail. Equally vital, Walker shows us that a thief doesn’t necessarily look like a thief.

12. A fragmentary scene in lip-sync—but limited lip-sync. Why? Because not everyone can read lines effectively. Also, shooting lip-sync means controlling set/location noise, not to mention adding a sound man to the crew.

13. Racetrack noise creates atmosphere with no strain on the budget.

14. Again, keeping it simple, holding down costs. Joyce doesn’t even have to be present.

15. No law says fact films have to be dull or devoid of humor. Here, Walker has combined a play on words and action into unanticipated contrast that’s a cinch to get a laugh even while it drives home a point.

* * *

16. Page 10 has our narrator explain steps to take to help prevent thefts. Here, on page 11, Walker gives further practical help to his audience, as well as information. Action and narration pinpoint behavioral red flags, things to watch for that may indicate thievery in the offing.

17. Walker and his technical advisors are aware that paranoia can be just as dangerous as playing patsy. Hence this warning against any temptation on viewers’ part to develop a Sherlock Holmes syndrome. The message is clear: Leave action to the Postal Inspectors. They know the law, the rules; what can and can’t be done.

18. Page 15, now; next to the last page of the script. With the Film’s conclusion approaching, Walker introduces the time-tested psychological device of a testimonial: Larry, the postmaster, is an authority figure, but a friendly one. Up from the ranks, broadly experienced, he points up a specific fault that illustrates the kind of thing that can lead to problems.

19. Finally, another laugh line, to close the film on a positive note and leave viewers feeling good, not browbeaten or hostile.

* * *

How did Walker research and develop Internal Crime Prevention?

“I talked to an inspection service agent,” he reports. “She told me what sort of guidelines they had in mind—what they wanted the show to do. Their goal was to alert postmasters and other supervisors on how to spot and therefore prevent theft by postal employees.

“Then I went to a post office and spent half a day interviewing the postmaster there. He showed me the ways that theft ordinarily is accomplished. And of course I grabbed all available printed information.

“After that, it was just a matter of thinking through and writing the script and having it checked.”

On a technical/format level, note that Walker has limited his use of optical effects to FADE IN and FADE OUT. This isn’t unusual today, both because there’s a tendency to eliminate dissolves and wipes in favor of straight cuts wherever possible, and because directors are inclined to ignore them even if the writer does insert them.

CHARIOTS OF FIRE (original screenplay), by Colin Welland.

In his native land they call Colin Welland a “professional Northerner”—north of England, that is. Well known as a TV actor and writer, characterized by a frizzy mop of curls and upon occasion described as “Harpo Marx with a double chin,” he’s achieved even greater respect in cinematic circles as the man who scripted Chariots of Fire, winner of the 1981 Academy Award for “screenplay written directly for the screen.” The film also claimed that year’s “Best Picture” honors and went on to become the highest-grossing imported film in the United States up to that time.

Chariots of Fire was by no means Welland’s first success. His previous major screenplays included Bangelstein’s Boys (1969), Roll On Four O’Clock (1970), Kisses at Fifty (1973), and Leeds United (1974). And in the years since, he’s gone on to Chaplin (1983), and The Yellow Jersey and Twice in a Lifetime, both still in the scripting stage.

Produced by famed David Puttnam for Britain’s Enigma Productions, Chariots is a totally unique picture. It centers on the true story of two sprinters as they clash in the 1924 Olympic Games. One, Harold Abrahams, is English and Jewish. The other, Eric Liddell, is the son of Scottish missionaries. The contrast between their divergent personalities, attitudes, and motivations, coupled with Welland’s refusal to resort to cheap shots and traditional hype in his script, is such as to create one of the period’s most memorable films.

People clearly are Welland’s passion. In every film he’s written, they are the focus.

Yet beyond this lie the factors of judgment and choice. A dozen times, a hundred, he must decide on the dynamics of each personality, and then pick and develop the incidents and color and details of setting that will best reveal the true nature of the man—or woman—under consideration.

It’s here that Chariots best provides us with insight into Welland’s talent. With deep practical knowledge of both psychology and film technique, he translates anti-semitism into Abraham’s experiences at King’s College, Calvinism into Edinburgh and the Scottish Highlands and Liddell’s preaching. Races become far more than running. Tags, traits, and relationships are made meaningful in terms of speech and action.

Rather than attempt to dissect the script itself, we’ll concentrate here on the creativity which Welland brought to bear on his project.

Excerpts of Chariots of Fire used with permission of David Puttnam and Enigma Productions, Ltd. All rights reserved.

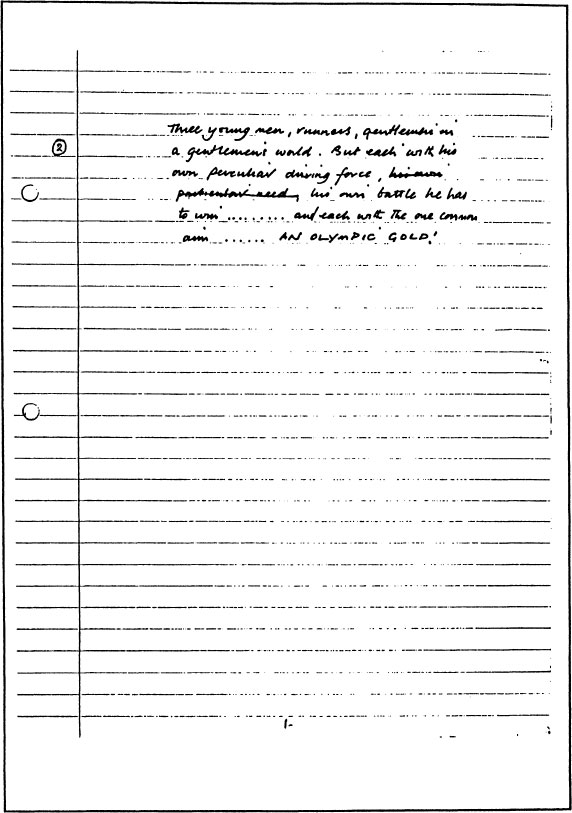

1. The cover sheet on Welland’s original treatment. Note that at this time, the project was titled 1924 Runners, rather than the ultimate Chariots of Fire.

Observe, too, that the date is 1978.

2. The concept for the film, captured in a single brief paragraph: “Three young men, runners, gentlemen in a gentlemen’s world. But each with his own peculiar driving force, his own battle he has to win … and each with the one common aim … AN OLYMPIC GOLD!”

3. The first page of Welland’s handwritten notes for the picture. Although he heads the presentation “Introduction,” it clearly is a laying-out of his own thinking as he ponders the background against which the proposed film must develop: a Europe still reeling in the aftermath of World War I, with all the political, sociological, and psychological trauma that implies. The very fact that Welland probed the situation in such depth can’t but have had an influence on the way he built the script.

4. “Breakdown of Story Line”: another step forward in the concept’s unfolding.

Note, too, that the title is now simply Runners.

5. The two major characters: their development; the events and heritage that have shaped them.

6. Passage of time, too. These men don’t spring onto the screen full-blown, nor are they one-dimensional. They’re different, unique human beings, each with a depth that gives him individual fascination for us, the audience.

7. As timespan and exploration of divergent aspects of characters’ lives grows, footage lengthens. Welland uses montage to hold it down, compress it.

8. Welland has thought through his characters and their contrasting values. Which means that he has a standard to write to for each. He’s established guidelines not only to tell him in advance how each will react in any given situation, but to help him devise appropriate, tension-building scenes and incidents … essential even in a “true” account such as this one.

9. We find more insight into Welland’s thinking in this undated letter to producer David Puttnam: “It’s an atmospheric film this,” he writes, “depending so much on mood and the creation of a visual time and place. If this is done successfully then my characters will suddenly take on a reality.”

The paragraph that follows makes clear how he’s feeling his way into the atmosphere he knows is so important and, simultaneously, is integrating his characters into it.

He also has “the complete story line laid out how”—worth noting here because it points up the stop-at-a-time procedure that goes with scripting: a denial that screenplays flash into a writer’s mind full blown.

This is perhaps a good place, too, to note that Welland is working with David Puttnam, a brilliant producer. Without in any way diminishing Welland’s role, undoubtedly the final script reflects the interplay of two creative minds.

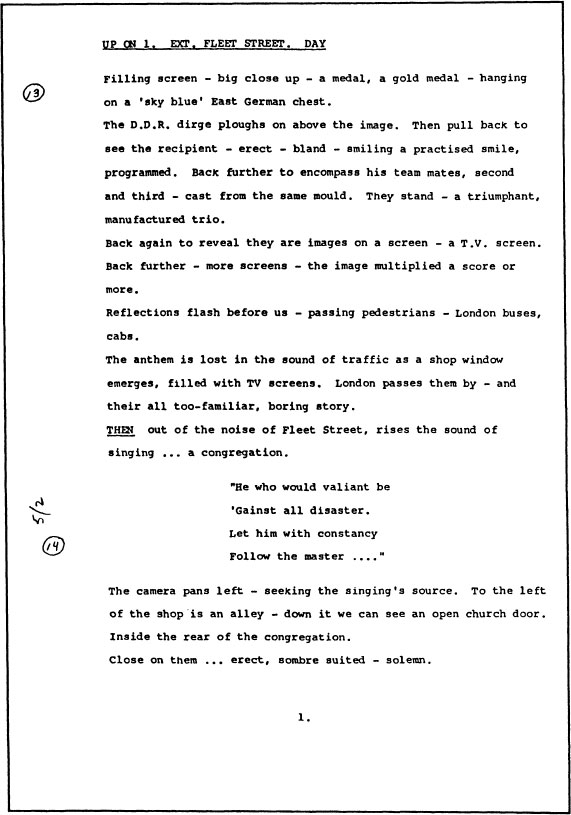

10. First draft of the script. It’s now April, 1979; nearly a year has elapsed since Welland submitted his treatment. Also, the title now has changed from Runners to Chariots of Fire.

11. Note the church interior setting.

12. June, 1979, and the second draft.

13. The church interior of the first draft has changed to a Fleet Street exterior, with television screens picking up East German Olympic winners.

14. Not for long, though. We return to the church interior from the first draft, with only minor changes.

15. February 13, 1980, and another version of the second draft.

16. A preface has been inserted. It helps to orient the film’s audience to the time, place, and circumstance of the picture. Yet in all likelihood it also was rooted in more than a little nail-gnawing and floor-pacing, for in film any delay in getting into the action is bound to constitute a calculated risk where the box office is concerned.

17. The script page that follows remains as before, however.

The point to be made here is that writing a film script—any film script—is a big job. To produce one as superior as Chariots of Fire is even more so. It took at least two years—probably more—of Colin Welland’s time and talent, not to mention the tedium and frustration that go with what sometimes seems like endless revision. Which is to say, it’s not a job for anyone who lacks staying power and the ability to work with others.

Observe, too, how many bits and pieces and ideas have been introduced and discarded in the course of the script’s development.

And if you’ve seen the finished film, you’ll recognize that even more changes took place while the picture was being shot and edited … par for the course in the very nature of things, no matter how upsetting to the person who wrote the script.

* * *

So, at last, we end these lessons from the pros; this glimpse at the way the old hands solve script problems.

But there’s still the question of where you fit into the world of film. It’s the topic of our final chapter.