Chapter 8

Getting Real: The Truth about Documentary

In This Chapter

![]() Analysing documentaries, including their ethical dilemmas

Analysing documentaries, including their ethical dilemmas

![]() Considering the development of documentary film

Considering the development of documentary film

![]() Untangling the real from the unreal in documentaries

Untangling the real from the unreal in documentaries

Documentary theorist Bill Nichols has claimed that, in a sense, all films are documentaries. Even the most fantastical fiction film provides information about the culture that produces it, as well as representing the actors and any physical locations used. With this thought in mind, he divides ‘documentaries’ into two categories: wish fulfilment (fiction films) and social representation (what people normally call documentaries).

You can accept Nichols’s argument for its own merits, while also noting the clear and significant differences between fiction and documentary films, specifically the elements that make each genuinely powerful. Documentary films are also notable for the ethical questions they raise by filming real people in their own environments, the decisions film-makers take to intervene and change events or to stand back and observe, and the relationship of the film image to a pre-existing reality. So read on; things are about to get real.

Shaping Reality with Documentary Films

Scottish director and producer John Grierson provided the most famous definition of documentary film. He may not have coined the term, but he certainly made it his own in a newspaper review of Robert Flaherty’s film about Polynesian culture, Moana, in 1926. A few years later he defined the documentary as ‘the creative treatment of actuality’. This definition is so influential because it acknowledges a surprisingly modern view of the documentary – viewers aren’t watching pure, simple reality on the screen, but a ‘creative treatment’ of it.

Comparing the documentary to fiction and to real life

The principal point of comparison for documentary film has always been its apparent opposite – the fictional narrative film. Early advocates of the documentary, including John Grierson and especially artist and film-maker Dziga Vertov, saw narrative cinema as a waste of the medium’s potential to show viewers the truth.

This analysis sees fictional films as problematic, because they obscure the deeper truths of society: in turn, the documentary is the solution to this problem. This argument has aesthetic and political implications. It places a set of public responsibilities upon the documentary, including the requirement to educate, inform and empower the viewing public by putting real life up on the cinema screen.

Table 8-1 Comparing Realism in Fiction and Documentary Film

|

Fiction Film |

Documentary |

|

Mise-en-scène (locations, props, costumes, though see Chapter 4 for a full discussion of the term) can be real (shot on location) or ‘faked’ in a studio. |

Mise-en-scène is found in real life. |

|

Even if the characters are real people, they’re played by actors, often stars. |

The characters are real people apparently being themselves. |

|

The camera, lights and other film-making apparatus remain unseen. |

The film-making apparatus can sometimes be seen within the film. |

|

The film-maker is an off-screen creative presence. |

The film-maker can appear in the film and may even be the star. |

|

Screenwriters create a narrative structure and dialogue. |

The story events unfold with their own logic, and dialogue is natural speech. |

|

Audiences accept the illusion of reality according to codes and conventions. |

Audiences expect a degree of truthfulness and transparency. |

Of course the boundary between documentary and fiction film is often far more blurred than the simple analysis in Table 8-1 suggests. Grierson and Flaherty’s notion of the documentary allowed film-makers to reconstruct or even stage moments, as well as give participants explicit directions. In Flaherty’s Nanook of the North (1922), his Inuit subject reacts with amazement and confusion at a phonograph, biting the record between his teeth. Flaherty admitted that Nanook was actually well accustomed to such technology and that the moment was a contrivance. (Flip to the later section ‘Exploring the world and its people’ for more on Flaherty and Nanook.) Reconstructions, whether subtle or spectacular – such as the thrilling climbing re-enactments in Touching the Void (2003) – are an essential element of the documentary film-maker’s toolkit.

- The relationship of the image to reality was a central question of philosophy well before film studies. Ancient Greek philosopher Plato described a cave with shadow images projected onto the wall. If you were a prisoner chained to the wall in that cave for your whole life, you’d perceive the shadows as reality, at least until you were released. The implication is that images are representation, not reality, but they nonetheless have to power to feel real under certain circumstances.

- Film can be thought of as a language that uses signs and symbols, and for this reason it has often been studied using methods borrowed from linguistics. Film semiotics thinks of images or shots as ‘signs’ or ‘indexes’ of a pre-existing reality. Semiotics stresses that the way humans think is through language, and that therefore reality only exists for humans as signs and indexes. (Flip to Chapter 11 for more on semiotics.)

- Postmodern theorists such as Jean Baudrillard argue that modern mass media have saturated people with images to the extent that these images have replaced reality. As an example, think about the terrorist attacks of 9/11: what do you see in your mind? I bet that your head is replaying the images broadcast in constant rotation on television: the plane hitting the second tower, the dust avalanche in the Manhattan streets. These images, to all intents and purposes, are 9/11.

You don’t need to go quite as far as Baudrillard – by disputing the existence of reality outside of images – to recognise that the truth value of the image is a crucial issue for producers and consumers of documentaries. An unspoken trust between film-maker and audience states that what you’re seeing on the screen is a close approximation of a real (or pro-filmic) event. Television news and reportage wouldn’t exist without this contract, which is constantly under renegotiation in the face of new recording technologies. For example, in recent years poor-quality digital video of news events recorded on bystanders’ mobile phones has taken on greater truth value than professionally captured images.

Sorting documentaries: Six modes

When attempting to define the documentary film, you realise quickly that many different styles of such film-making exist, each with its own formal structure and aesthetic strategies. Responding to this diversity, Bill Nichols came up with a set of six subcategories, or modes, of the documentary:

- Expository documentaries: The traditional form, which uses an authoritative voice-over or presenter to address viewers directly and argue a case about history, nature or politics. A good recent example is Al Gore’s passionate plea for action against global warming, An Inconvenient Truth (2006).

- Observational documentaries: Aim to show everyday life as it is, with minimal intrusion by the film-maker or film-making process. Also known as ‘fly on the wall’ films, they’re most commonly found on television, but influential film examples include Frederick Wiseman’s Titicut Follies (1967), an exposé of the treatment of mental-health patients.

- Participatory documentaries: Feature the film-maker as an on- or off-screen presence, who nonetheless retains an objective stance on events. Participants are interviewed as witnesses who testify for or against a particular case, and these films may also use archive footage or reconstructions. The Oscar-winning Man on Wire (2008) demonstrates a creative use of this mode.

- Performative documentaries: Share similarity with participatory documentaries, but the film-maker appears on-screen and also intervenes directly in events. Interviews are staged and encounters are often dramatic and surprising. The documentary becomes as much about the film-maker as the subject. Michael Moore’s films (such as Bowling for Columbine (2002)) are great recent examples.

- Poetic documentaries: May be based on any of the six modes but have strong aesthetic or sensual forms that bring them closer to the feeling of poetry than prose. This mode includes many early documentaries, such as Night Mail (1936) with its rhythmic commentary written by poet WH Auden, or avant-garde films such as Stan Brakhage’s Window Water Baby Moving (1959) (see Chapter 7).

- Reflexive documentaries: Explicitly comment on their own status as documentaries, through stylistic means (for example, by disrupting conventions such as the voice-over) or by featuring conversations about the nature of documentary truth. See Nick Broomfield’s Driving Me Crazy (1988), which is about the film-maker’s failed attempts to make a documentary.

Weighing documentary ethics

A long-standing story in Western culture claims that when members of primitive tribes are faced with a camera for the first time they cower, fearing that the technology is going to steal their souls. Whether based on truth or not, this story is a useful analogy of a dilemma that documentary film-makers encounter. How can you capture the truth about your subjects when your presence and your equipment inevitably change your subjects’ behaviour? And in ethical terms: how should you treat the human subjects of documentary? Even if the camera doesn’t steal subjects’ souls, it may damage their lives after the film is released.

Film-makers have to make countless ethical decisions to maintain a balance between observation and intervention. Where this balance lies is a fundamental measurement of the different philosophies of documentary making, from classic works of cinéma vérité (check out the later section ‘Reclaiming objectivity: Direct cinema and cinéma vérité’) to today’s omnipresent reality TV.

The observational style of Titicut Follies appears to show the real world without intervention. But of course this impression is a carefully crafted illusion. Wiseman’s methodology of spending several weeks within an institution in order to shoot his material results in a huge amount of footage, and so every editing choice becomes an ethical decision on what to show and what to leave out. Documentary film-makers often see part of their role as confronting society’s taboos, the things that people are too scared to talk about, but they must do so sensitively.

Capturing the 20th Century on Camera

The term documentary relies upon the notion of the document, a piece of evidence in all senses, for lawyers, scientists and historians. For future historians looking back on the 20th century, documentary films are likely to be among the richest documents. Covering the entire 100-year span, from the earliest so-called actualities produced by the Lumière brothers in France to the digital experiments of 1999 such as the BBC’s Walking with Dinosaurs, film-makers used a bewildering array of styles, techniques and methodologies to document the world on screen.

Faced with this rich history and diversity, knowing where to start can be difficult. So this section focuses on a few specific moments and places where documentary flourished.

Meeting plain-speaking Russians

Cinephiles may regard John Grierson (whom you can meet in the earlier section ‘Shaping Reality with Documentary Films’) as the father of the documentary movement in Britain and the West, but he was by no means the only pioneer in the field.

- Narrative film, with its reliance on devices from other art forms such as literature and theatre, is ABSURD and DANGEROUS.

- The camera and the camera operator MUST join together as one organism to observe TRUTH through the KINO EYE (‘kino’ is Russian for ‘cinema’).

- KINO-PRAVDA (‘cinema truth’) OPENS up the film-making process to the audience and BREAKS THE SPELL of the cinema.

As good as his word, Vertov formed a group known as Kino Eye, made up of his editor wife, Elizaveta Svilova, and his cameraman brother, Mikhail Kaufman, to produce newsreels under the banner Kino-Pravda. The results are rather different to the static newsreel style with which you may be familiar, and they feel more like avant-garde experiments than pieces of journalism. Vertov filmed everyday life (schools, factories and so on), without the permission of his subjects, and used cinematic tricks in order to reveal deeper truths about society. For example, in a sequence designed to illustrate how bread is made, the bread pops out of the oven first and is then visually rewound into a field of corn. INGENIOUS.

Exploring the world and its people

During the first half of the 20th century the British Empire still covered a quarter of the globe, but even the Brits hadn’t reached a few bits of the world. Explorers gripped the public imagination with reports of high-profile expeditions to the North or South Poles and even the ‘top of the world’, Mount Everest. But obvious logistical challenges blocked these pioneers from capturing their adventures on film.

Camera operators needed to be explorers in their own right, and famous examples from the 1910s included the Australian Robert Hurley (whose South (1919) documents Herbert Shackleton’s Antarctic expeditions) and the British Herbert Ponting. Ponting accompanied the ill-fated Terra Nova expedition to the South Pole from 1910 to 1913 in which Robert Scott and his four comrades lost their lives.

The travelogue form proved open to detailed studies of places or people, with explorers providing footage for scientific or economic reasons. Robert Flaherty saw himself as an explorer first and film-maker second. He was the son of a prospector who searched large areas of the Canadian wilderness on behalf of steel companies, and as an adult he entered the profession establishing routes for railroads. During these expeditions Flaherty built close relationships with a tribe of Inuit people and began to take short films of them. The resulting footage was accidentally destroyed, and so he set out again, this time specifically to make a film about an Inuit family with whom he was well acquainted. The resulting film, Nanook of the North (1922), was one of the first feature-length films to resemble today’s documentaries.

Filming poetry or propaganda? World War II on film

World War II wasn’t the first conflict to be committed to celluloid. Extensive newsreels of World War I survive, as well as some longer propaganda films, such as the partly re-enacted Battle of the Somme (1916). Even the Boer war of 1899 to 1902 leaves a few cinematic traces. But World War II arrived at the peak of film’s popularity as an art form, and the circumstances of war triggered record cinema audiences. Before television was the primary news medium, cinema newsreels were the only way for people to see the war for themselves. Unsurprisingly governments on both sides waged war on public hearts and minds with propaganda films.

- Target for Tonight (1941): Director Harry Watt used dramatic reconstructions to create an effective and exciting recreation of an RAF bombing raid over Germany; audiences loved it.

- Listen to Britain (1942): Humphrey Jennings’s impressionistic account of the sounds of wartime Britain included spitfire engines and heavy industry but also birdsong and classical and popular music.

- Western Approaches (1944): An ambitious Technicolor film shot by the master of colour cinematography, Jack Cardiff, which blends documentary footage with dramatic reconstruction using real members of the Merchant Navy.

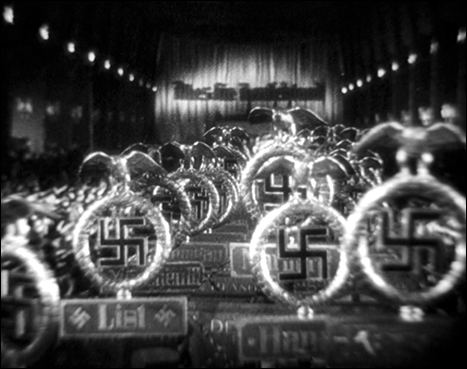

Propaganda is a difficult term to define, but you can think about it simply as documentaries that your enemies make. From the Nazi perspective, the films of Humphrey Jennings were hardly poetry – after all, one scene in Listen to Britain depicts a recital by the Jewish pianist Myra Hess being attended by Queen Elizabeth II. Similarly, the films produced under the Nazi regime, most famously Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph des Willens (Triumph of the Will) (1935), can never escape the circumstances of their production. Riefenstahl remains a divisive figure within cinema history because her obvious talents as a film-maker are weighed against her terrible ideological compromises.

Above all, the documentaries that both sides produced during World War II demonstrate that ‘truth’ is a relative concept, inescapably tied to politics and historical context.

Courtesy Everett Collection/REX

Figure 8-1: The fearful symmetry of Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will (1935).

Reclaiming objectivity: Direct cinema and cinéma vérité

After World War II demonstrated the heroic and horrific consequences of claiming cinematic truth for political ends (see the preceding section), the documentary form seemed inevitably compromised. After wartime propaganda revealed the manipulative nature of apparently objective documentaries, how do you put that genie back in the bottle? Restoring the truth value of the documentary took some time, as well as a radical technological shift.

The technology required to record images and sound is particularly important for documentary film-makers who most often work on location (as opposed to on a sound stage):

- In the days before sound on film, the silent, hand-cranked camera was relatively portable, although hardly unobtrusive. Watch Man with a Movie Camera for examples of how this type of camera looked in action on the streets.

- During the 1930s and 1940s, the requirement to shoot lip-synced dialogue on 35-millimetre film meant that cameras and recorders became much larger and heavier, reducing portability and the ability to record spontaneous action.

- By the end of the 1950s, several technological advances came together, including better 16-millimetre film stock, lenses for shooting with natural light and especially smaller, lighter (and sometimes integrated) sound recorders.

- By 1962, camera operators were able to hand-hold or rest on their shoulders the Nagra IIIB camera, allowing mobile shooting with minimal interference.

Although the new portable film-making technology reinforced the truth value of the recorded images and sounds, the ethical problem of the film-maker’s own presence didn’t go away (see the earlier section ‘Weighing documentary ethics’). In fact in some ways it became heightened, because the possibility of entirely secret, unauthorised shooting opened up new ethical issues.

Table 8-2 Differences between Direct Cinema and Cinéma Vérité

|

Direct Cinema |

Cinéma Vérité |

|

To obtain truth from the subject, the film-maker should be as unobtrusive as possible. |

To obtain truth from the subject, the presence of the film-maker must be acknowledged or even discussed. |

|

The principal method is observation of subjects behaving within their environment. |

The principal method is participation between film-maker and subject, often through interviews. |

|

Commentary is minimal or absent so that subjects can speak for themselves. |

Commentary is vital, whether in voice-over or through on-screen presence. |

|

The audience members should forget the film-makers and feel as if they’re in the room with the subjects. |

The audience is free to identify with the film-maker’s or the subject’s position and point of view. |

|

The film-maker is a ‘fly on the wall’, watching but practically invisible. |

The film-maker is a ‘fly in the soup’, intervening to get a response. |

Blending the Real and the Unreal: Documentary Today

Surprisingly, a significant number of feature-length documentaries have achieved financial success in cinemas in the 21st century, most notably the political films of Michael Moore and the nature documentary March of the Penguins (2005). But popularity has led to an increased level of concern about the depictions of ‘reality’ in these films. Similar concerns apply to documentaries in today’s digital world: if documentaries are real human stories on film, what happens to the form in the age of social media, when many people’s stories, if not their very identities, are constructed online?

In today’s multiplexes, the real and the unreal seem increasingly intertwined.

Questioning America the beautiful

The American independent film-making sector has produced a recent spate of hit cinematic documentaries, characterised by a left-wing political agenda that launches attacks on big business and government policy. But these films are a world away from didactic history lessons or even the cool detachment of direct cinema (see ‘Reclaiming objectivity: Direct cinema and cinéma vérité’ earlier in this chapter). On the contrary, they feature big personalities, passionate rhetoric and emotional as well as political engagement.

The key figure of this style of documentary is an apparently unassuming regular Joe in baseball cap and jeans: Michael Moore. His first film, Roger & Me (1989), is an account of the damage done by General Motors to his hometown of Flint, Michigan, and his later films build upon this highly personalised, subjective approach.

- Personal biography: Moore starts the film in his hometown where he attempts to open a bank account that includes a free gun.

- Interviews: Moore interviews witnesses to the 1999 Columbine school shootings, as well as representatives from organisations such as weapons manufacturers Lockheed Martin and celebrities including Marilyn Manson.

- Animation: Moore parodies the animation style used in children’s educational films to illustrate the history of America’s relationship with firearms.

- Archive footage: Moore assembles a montage sequence of US foreign policy from 1953, which claims that the CIA trained Osama Bin Laden against the Soviet Union some 30 years before 9/11. It’s set to the ironic counterpoint music of ‘Wonderful World’ sung by Louis Armstrong.

Moore’s grand claim concerns America’s addiction to fear, which politicians, the media and big business peddle to further their own interests.

Bowling for Columbine paved the way not only for Moore’s even more controversial and financially successful Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004), but also for other documentary film-makers using maverick techniques, such as Morgan Spurlock. Spurlock put his own health in jeopardy to make Super Size Me (2004) by eating only McDonald’s food for a month. Although he offers clear and indisputable evidence that doing so isn’t good for human health, his experiment raises interesting questions about a documentary film-maker’s right to damage his own body to make a point. His doctors and his mother advise him to stop, but he goes on with his ‘challenge’ regardless. In this case, the ends did justify the means, because McDonald’s officially withdrew Supersize meals soon after the film’s release.

Marching with penguins and other creatures

Eadweard Muybridge, pioneer of the series photography that made cinema possible, invented his proto-projector zoopraxiscope device (in 1879) in order to settle an argument: namely, when horses run do all four legs ever leave the ground at one time? Turns out, they do. This event is the earliest example of the potential of cinema to help people understand the natural world. Cinema audiences have shown a keen interest in wildlife films ever since:

- Robert Flaherty and Herbert Ponting’s exploratory films of the 1920s contain many scenes of animals in their natural habitat.

- Walt Disney produced a popular series of ‘True Life Adventure’ films in the 1950s, such as the Oscar-winning The Living Desert (1953); Disney recently re-entered the market with films such as African Cats (2011).

- The ultra-large IMAX format, which grew in popularity during the 1990s and 2000s, reinforced the spectacular nature of wildlife films (Alaska: Spirit of the Wild (1997), for instance).

- On television, the BBC’s flagship nature documentaries narrated by David Attenborough are popular with audiences across the world, with some being adapted for cinema release (notably The Blue Planet (2001)).

The fact that the revival of the cinema documentary in the 2000s was partly led by waddling penguins therefore seems appropriate. March of the Penguins (2005) started life as a French independent production. Warner Bros. picked it up, gave it a new score and a Morgan Freeman voice-over, and heavily marketed it at family audiences. The campaign clearly worked; the film’s gross of $77 million in the US alone makes it the second most successful documentary of all time (behind Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11).

Documenting digitally

New technology has reinvigorated documentary film in the 21st century. The digital revolution puts cameras into people’s pockets, and the Internet allows them to create and share instantly video of their lives with millions of users around the globe. In such a world, as a film student you have a responsibility to question how real these stories (and indeed these people) are. (Chapter 16 explores the digital revolution in greater detail.)

You can also view the sharing of identities online in a far more positive, utopian fashion. Crowd-sourcing via the Internet has become a possible source of finance for film-makers and also presents opportunities for ambitious collaborative projects such as Life in a Day (2011). Instigated by Ridley Scott and Kevin Macdonald, the team chose a date (24 July 2010) at random and asked volunteers to film what they were doing, answer a few specific questions (such as ‘What is in your pocket?’) and upload the results. Nobody on the team was sure that they’d receive enough high-quality footage to produce a feature-length film. In the end the team were sent more than 81,000 submissions from 192 countries, totalling more than 4,500 hours of video.

Even in the digital age, however, the spread of technology is far from universal, and the team resorted to sending digital cameras to the developing world in order to guarantee global coverage. Macdonald later conceded that better training would have resulted in more of this footage being used, because even the concept of ‘documentary’ was foreign to many in the most far-flung regions. Despite this unwelcome puncturing of New-Age Internet universality with old-world problems, the team worked hard to assemble a coherent film from the many hours of material, using the temporal structure of a single day to unite people across the world doing mundane or life-changing things. It is this clarity of purpose brought by impressive editorial control that makes the film truly memorable.

Nichols is deliberately overstating his case in order to emphasise the similarities and crossovers between the two forms of film-making. In particular, he wants to overturn the notion that only fiction films tell stories. Documentaries are often as exciting and dramatic as narrative films, and generally less predictable, because they draw their subject matter from real life. Of course, the boundaries between the two forms are notoriously flexible, with many documentaries using techniques from fiction film to recreate events – and fiction borrowing heavily from documentary for its enhanced ‘truth value’ (that is, the implied authority of the documentary image).

Nichols is deliberately overstating his case in order to emphasise the similarities and crossovers between the two forms of film-making. In particular, he wants to overturn the notion that only fiction films tell stories. Documentaries are often as exciting and dramatic as narrative films, and generally less predictable, because they draw their subject matter from real life. Of course, the boundaries between the two forms are notoriously flexible, with many documentaries using techniques from fiction film to recreate events – and fiction borrowing heavily from documentary for its enhanced ‘truth value’ (that is, the implied authority of the documentary image). Film-makers make documentaries that are more than simply reality captured on camera. The decisions they make before, during and after shooting alter that reality into something else, like Grierson’s notion of a ‘creative treatment’. But what about the status of the individual image or shot in relation to real life? How real is real? Time to go deeper for a moment. Stick with me:

Film-makers make documentaries that are more than simply reality captured on camera. The decisions they make before, during and after shooting alter that reality into something else, like Grierson’s notion of a ‘creative treatment’. But what about the status of the individual image or shot in relation to real life? How real is real? Time to go deeper for a moment. Stick with me: In order to decide whether a documentary fits into one of Nichols’s six modes, compare the use of one particular element across different films – the interview. The interview is a formal device common to almost all documentaries, but film-makers can employ it to very different ends. In expository or observational films, the film-maker gives interviewees visual preference and allows them to speak for themselves with little intervention or prompting. Participatory, reflexive and performative documentaries include dialogue between film-maker and interviewee, but the differences lie in the levels of intervention and insertion of the film-maker’s personality. Poetic treatments may focus on the interviewee’s voice or body language rather than the content of what the person says.

In order to decide whether a documentary fits into one of Nichols’s six modes, compare the use of one particular element across different films – the interview. The interview is a formal device common to almost all documentaries, but film-makers can employ it to very different ends. In expository or observational films, the film-maker gives interviewees visual preference and allows them to speak for themselves with little intervention or prompting. Participatory, reflexive and performative documentaries include dialogue between film-maker and interviewee, but the differences lie in the levels of intervention and insertion of the film-maker’s personality. Poetic treatments may focus on the interviewee’s voice or body language rather than the content of what the person says. Frederick Wiseman’s Titicut Follies, which observes life inside a home for the criminally insane in Massachusetts, was a controversial film for many reasons. It displays practices of which the American public were generally unaware, including patients being force-fed, bullied or forced to wander round naked. Although Wiseman was careful to obtain permissions from all participants (or their legal guardians), after the film was completed in 1967 the state government of Massachusetts banned it, giving the reason that it violated the privacy of patients. Despite Wiseman’s continued appeals on the grounds of infringement of civil liberties, the film remained off-limits to all audiences except health professionals until 1991.

Frederick Wiseman’s Titicut Follies, which observes life inside a home for the criminally insane in Massachusetts, was a controversial film for many reasons. It displays practices of which the American public were generally unaware, including patients being force-fed, bullied or forced to wander round naked. Although Wiseman was careful to obtain permissions from all participants (or their legal guardians), after the film was completed in 1967 the state government of Massachusetts banned it, giving the reason that it violated the privacy of patients. Despite Wiseman’s continued appeals on the grounds of infringement of civil liberties, the film remained off-limits to all audiences except health professionals until 1991. Like many a mad genius, his contemporaries at home or abroad didn’t widely appreciate Vertov. Eisenstein critiqued his attack on fiction film and called him a ‘film hooligan’ – a label that probably pleased Vertov. For Grierson, whose very different vision of the documentary was to become the dominant expository mode, Vertov’s tricks and self-reflexivity were ‘ridiculous’ and ‘too clever by half’. Yet Vertov later influenced cinéma vérité, a movement that agreed that the film-maker should be in the film (see ‘

Like many a mad genius, his contemporaries at home or abroad didn’t widely appreciate Vertov. Eisenstein critiqued his attack on fiction film and called him a ‘film hooligan’ – a label that probably pleased Vertov. For Grierson, whose very different vision of the documentary was to become the dominant expository mode, Vertov’s tricks and self-reflexivity were ‘ridiculous’ and ‘too clever by half’. Yet Vertov later influenced cinéma vérité, a movement that agreed that the film-maker should be in the film (see ‘