Chapter 13

Theorising about Film: How Movies Work

In This Chapter

![]() Revealing the big ideas of film theory

Revealing the big ideas of film theory

![]() Theorising film texts with Marxism

Theorising film texts with Marxism

![]() Using other academic disciplines to analyse films

Using other academic disciplines to analyse films

I’m going to be upfront with you: film theory isn’t easy. Most theory involves outdated, jargon-laden language, and even after you decode the written style, the central concepts can be tricky to get your head around. Add to that the fact that many of the important film-theory books and articles take part in a philosophical conversation with other complex, jargon-heavy ideas that you’ve probably never heard of, and you have a recipe for giving up, throwing your film-theory book across the room and going to watch The Hunger Games movies on Netflix to work through your frustration. So, why bother?

If you don’t think these questions are worth thinking about, you can skip this chapter. But then again you’re reading this book, and so I hope that you do care about this stuff. Plus, millions of film students around the world have grasped these ideas successfully and you can too. So stick at it, soldier. One day you’ll be glad that you read this chapter and therefore know how film connects to some of the great ideas of the last hundred years or so: formalism, Marxism, structuralism and psychoanalysis.

Building a Foundation of Film Theory: Text, Context and Spectator

Not all types of film theory engage with all three elements to the same extent: some focus on just one (such as formalism) and others concern themselves with the relationship between two elements. For example, as well as formalism, in this section I describe notions of realism, which are largely about the relationship between the text and its context, and reception theory, which examines the relationship between the spectator and the text.

Formalism: What is a film?

In order to understand something, you have first to know what it is. This statement may sound blindingly obvious – it’s a film, you fool. But how do you know it’s a film? What are its basic formal properties and how are these similar or different from other cultural forms?

Formalism tries to address several specific issues, notably:

- What makes art different from communication? The formalists identified that poetry and metaphor are vital elements of literature. Viktor Shklovsky argued that artists defamiliarise the everyday world by making it seem strange and unfamiliar. This idea often relates to avant-garde film or art cinema (check out Chapter 7).

- Do groups of texts work in similar ways? Several formalists laid the foundations for genre theory and structuralism (see Chapter 5 and the later section ‘Taking Films to Bits: Structuralism’, respectively) by linking groups of texts together. They analysed folk tales, for example, and yielded common characters and narrative elements. Literary theorist Tzvetan Todorov applied psychoanalysis (flip to the later section ‘Getting into Your Head: Psychoanalysis and Film’ for details) to discover new genres, such as the fantastic, which blurs the lines between reality and fantasy.

- How is a text affected by its context (how it is made, for example)? More recent neoformalist critics such as Kristin Thompson rethink formalist ideas with renewed focus on production context. Thompson points out that the notion of defamiliarisation requires you to first understand the everyday world of a film’s contemporary audience.

Realism: Does film reflect reality?

Whereas formalism is mainly about the film text itself, the many theories that come under the banner of realism investigate the complex relationship between a text and its context.

Some key debates around realism include:

- Which of film’s particular qualities are more realistic than others? André Bazin was a key critic of the French film journal Cahiers du Cinéma and a firm advocate of realism as the destiny and the goal of cinema. Bazin praised not only the documentary-style aesthetics of Neorealism, but also commercial film-makers such as Orson Welles for his use of deep focus and long takes, which both avoid the artificial intervention of editing.

- What’s the relationship between realism and fantasy in cinema? Early film historians noted two primary drives of film represented by the actualities (everyday scenes) of the Lumière brothers on the one hand and the fantasy of George Méliès on the other. In particular, Jewish German sociologist Siegfried Kracauer argued that the Expressionist flight from reality in 1920s films indicated a fear of chaos and disorder within German society that made it vulnerable to fascist control (for more on Nazi aesthetics in documentary film, see Chapter 8).

- How does digital film-making relate to the real world? Film theorist Stephen Prince suggests that computer-generated imagery (CGI) compromises the direct relationship between photographic cinema images and reality, and that a different kind of perceptual realism will replace photographic realism, asking: do the images look real or move realistically?

Reception: What is a spectator?

The obvious danger of the formalist approach to cinema (check out the earlier section ‘Formalism: What is a film?’) is that if you spend too much time thinking about what a film is, you can forget that a film doesn’t provide the same experience for each individual spectator.

Other important questions that reception theory poses include:

- How do individual spectators respond to real texts? Early film theory presented a model of a passive spectator who believed everything she saw. In contrast, cultural theorist Stuart Hall argues that spectators can read a film in many possible ways, including in an oppositional mode where the viewer rejects prescribed meaning and creates her own.

- What’s the role of viewing context in understanding a film? Major currents of film theory, such as structuralism (see ‘Taking Films to Bits: Structuralism’ later in this chapter), remove spectators from their historical context. Film theorist Janet Staiger argues instead for a focus on context as the fertile middle ground between the text and spectator, and for historical rigour when collecting evidence.

- How do people remember their viewing experiences? Research on memories of cinema-going suggests that people remember snippets rather than entire films, and that where you see films and with whom can dominate your recall. Annette Kuhn’s work on cinema memory combines autobiographical and historical approaches.

Shaping Society with Film: Marxism

American president John F Kennedy was apparently fond of an anecdote about the revolutionary philosopher Karl Marx. Marx struggled financially for most of his life, working mainly as a journalist, and while employed by the New York Herald Tribune as a foreign correspondent he repeatedly complained about his meagre salary. When his complaints fell on deaf ears, Marx quit journalism to write books including Das Kapital (1867–1894), which, directly or indirectly, led to the Russian Revolution, Stalinism and the Cold War. If only the editor of the newspaper had been a little more generous, the 20th century may have turned out a little differently.

This section comes over all radical, as I describe how film theorists have employed Marx’s ideas, fortunately to less violent ends.

Meeting Marx (Karl, not Groucho)

For Marx, Hegel’s model of history was used to explain the development from medieval feudalism (where lords and kings controlled serfs) to capitalism, and to predict that capitalism would eventually give way to communism.

Figure 13-1: The place of culture in Karl Marx’s model of society.

- The structure of the Hollywood studio system during the 1920s, including the dominance of Paramount, against which new competitors such as Warner Bros. were forced to take risks with new technology.

- The amount of leisure time and disposable income of the film’s large urban audiences.

- The celebrity of Al Jolson, a Broadway star who drew on long traditions of Jewish theatrical performance that pre-date US society.

- The tension between family and fame that drives the narrative, including the importance of family within Jewish immigrant populations.

Spending time with the Frankfurt School: Fun is bad

The Frankfurt Marxists’ account of culture also suffers from a disregard for the individual spectator and what she may do with a text. The Frankfort critique of mass media assumes that people simply accept what they’re told at face value and then go about their proletariat business. This approach is sometimes called a hypodermic needle model of the audience, because they remain passive while being injected with culture, to which, as with an illegal drug, they may become addicted.

Subsequent Marxists maintained their belief in Marx’s model of society, but sought to correct this imbalance by paying greater attention to how the spectator engages with the text.

Negotiating between culture and behaviour: Ideology

If James Brown is the Godfather of Soul, Louis Althusser is the Godfather of film studies (though with less sweating!). Althusser recast the Marxist critique of culture with an absolutely essential additional concept: ideology.

Living under capitalism, people constantly encounter logical contradictions or tensions between opposing ideas. Ideology works by dispelling these tensions with false but convincing solutions. For example, managers often find that the needs of their business conflict with their workers’ personal lives, but they can rely on the ideology of ‘competitiveness’, which is encouraged by government policy, to help them sleep at night.

Taking Films to Bits: Structuralism

Structuralism grew out of formalism, but instead of studying individual texts it takes groups of films to bits to discover their underlying commonalities. The following sections break apart the pieces.

Linking linguistics and film: Saussure

Here’s a word: ‘cinema’. When you read this word, you probably conjure up an image in your mind of a large, dark room where people go to watch films together in public. But why? Nothing about the word ‘cinema’ directly links it to that darkened room. In itself, ‘cinema’ is just a sequence of six letters, a collection of individual sounds that join together to form the word. If you’re an English speaker, at an early age you connect the large dark room with the sequence of sounds that is cinema, and then later you discover how to read and write the word. This process becomes instinctive.

- The signifier is the set of letters on a page or the sounds made when the word is spoken.

- The signified is their meaning.

The relationship between the signifier and signified is arbitrary. The word ‘cinema’ contains nothing inherently cinema-like about it. Other languages use different signifiers for the same sign (for example, kino in German). Language also creates meaning through difference, and so ‘cinema’ isn’t ‘theatre’ or ‘museum’.

So what does all this talk about language have to do with film? Well, a sign doesn’t have to be a written or spoken word – it can also be an image. If a film opens with a shot of the Empire State Building, you probably assume that the story is set in New York City. Here the image of the famous building functions as a signifier for the larger sign of New York. If the following shots are streets filled with yellow cabs, you know that you were correct in your assumption. But if, on the other hand, the Empire State is followed by shots of Big Ben in London and the Eiffel Tower in Paris, you guess that the story is international in setting, such as a James Bond film.

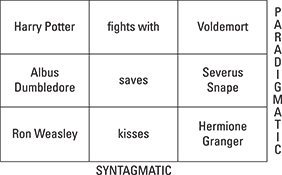

This example illustrates that meaning isn’t only produced by individual signs, but also by signs linked together, as with a sentence on a page or a sequence within a film. Saussure pointed out that these meanings can be changed in two ways (see Figure 13-2). Meaning and, in this case, narrative accumulates through the combinations on the syntagmatic axis (derived from the more familiar term ‘syntax’, meaning sentence structure), whereas different choices made on the paradigmatic (from ‘paradigm’, or pattern of thought) axis can create very different narrative outcomes.

Whereas in theory Harry could choose to kiss either Hermione or Voldemort, we know that these choices have already been set by JK Rowling and the film’s screenwriters. Nonetheless, less conventional possibilities exist, thanks to the variety and flexibility of language and storytelling. Consider the phenomenon of internet fan or slash fiction, which takes well-known characters in unpredictable directions.

Figure 13-2: Saussure’s semiotic possibilities applied to the Harry Potter universe

Sampling film semiotics: Metz

Saussure’s theories of semiotics were designed to be applied to written and spoken language. Applying the theories to other types of communication presents exciting possibilities for new critical interpretations – but also highlights the differences between language and other cultural forms.

French theorist Christian Metz was the first to think through the complex implications of applying semiotics to film. His work is driven by two central questions:

- Is film really a language?

- If so, how do you map the constituent elements of the two systems (language and film) onto each other?

- With Saussure’s sign, the relationship between the signifier and the signified is arbitrary. Metz argued that the mechanical reproduction of reality found in the photograph and hence cinema image meant that this relationship wasn’t down to chance. Cinema directly reflects reality instead of recreating it in symbolic fashion as language does.

- Saussure’s rules of language (which he called la langue) depend on difference between a limited number of options (for instance, cinema isn’t theatre). But cinema images are potentially infinite in variety, meaning that the paradigmatic axis is open, not closed as with la langue. In other words, we can’t define an image of a dog by saying that it isn’t a cat, or a pig, or a hamster, because this process could potentially go on forever.

- Metz argued that an image of a revolver in cinema means not just ‘revolver’ but ‘here is a revolver!’, which raises the question: does this make an image more like a sentence than a single sign or word? The problem here is that an individual image can’t be broken down into smaller units of meaning.

Despite the complicating issues, Metz concluded that the syntagmatic axis of language, where meaning accumulates sequentially, is applicable to narrative cinema, because it constructs time and space using shots that produce meaning in relation to one another (again, consider the New York City establishing sequence).

Meeting mythic structures: Lévi-Strauss

As well as producing hard-wearing jeans (no, not really), the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss was so impressed with Saussure’s linguistic structuralism that he decided to apply it to entire cultures. He claimed that you can discuss anything from cooking to clothing as a language in terms of its use of signs and structure.

But here I’m most concerned with Lévi-Strauss’s structural analysis of mythology, because it examines the status of stories within culture. His argument is pretty straightforward:

- Myths and legends told across the globe are hugely diverse but can all be boiled down to similar structures in their essence.

- Myths work like language in that they’re comprised of individual units of meaning, or mythemes, combined into particular patterns.

The underlying structures of myths are organised as binary oppositions, such as culture/nature, man/woman, good/bad and so on.

The underlying structures of myths are organised as binary oppositions, such as culture/nature, man/woman, good/bad and so on.- The purpose of myths is to solve magically all the tensions and oppositions that you observe in the world and make you feel better.

Although culture has moved on a little since the days of myths and legends, clearly people still tell stories to make themselves feel better. Therefore, suggesting that film-making has taken on this function within society isn’t much of a leap, particularly when you consider that film genres exhibit remarkably similar basic structures over time and across different cultures.

Lévi-Strauss’s mythic structures operate at an unconscious level, and so bear in mind that storytellers aren’t necessarily aware of why they use them or why audiences enjoy them.

Getting into Your Head: Psychoanalysis and Film

As a method of criticism, psychoanalysis works for all films, not just those that use the therapeutic process as a storytelling device or seek to explain the behaviours of heroes or villains through reference to traumatic childhoods. Also, a film doesn’t need to be explicitly surreal in visual style or dreamlike in structure. If psychoanalytic film theory works, it works universally. In this section I discuss the connections between dreaming and cinema, and how films may help to create our sense of ourselves. I also trace the importance of psychoanalysis within feminist film theory.

Delving into dreams: Freud and film

Sigmund Freud is credited with creating the practice of psychoanalysis, and his ideas on how the mind works are so influential that many of them have seeped into common usage. If someone unwittingly says something revealing, you attribute the slip to Freud. If a middle-aged man pulls up next to you in a bright red sports car, you roll your eyes and conclude that he’s overcompensating for a lack of sexual prowess.

- The human condition is an eternal conflict between your own drives and desires and the requirements that civilisation and culture impose.

- This conflict helps to create the three-part structure of your psyche: the id, the ego and the superego. You’re born with your id, which is a seething mass of unregulated desire. Becoming an adult means developing a conscious and rational ego to moderate the id, as well as a strict superego, which is the internalised voice of authority.

- The poor, overworked ego spends its days negotiating between the chaotic, unruly id and the dry, authoritarian superego in order to keep just about sane. In the process, much of what your id desires is repressed into your psyche. But repression doesn’t destroy desire, it merely delays it or converts it into other drives.

- While your rational ego is asleep, your dark, repressed desires escape into your dreams, typically in disguised, symbolic forms. Therefore, interpreting dreams can provide the key to understanding your psyche.

- Cinema can be viewed as a kind of collective dream, and so applying Freud’s methods of interpretation to films can reveal the hidden desires of the author, or, more interestingly, those of the audience, who use the film as a fantasy space to play out their own desires.

Freud started this work by analysing myths, most famously the story of Oedipus from Greek legend. Oedipus is a tragic figure who, due to a long sequence of events, ends up killing his father and marrying his own mother. Freud claimed that this narrative was an analogy for psychological development in children, with all people going through phases of desiring their mothers and wanting to kill their fathers. As disturbing and bizarre as this sounds, you can easily find similar structures in mainstream cinema when you choose to look for them: Luke, I am your father… .

Leaping through the looking glass: Lacan

Okay, take a deep breath, because in this section things start to get complicated. Jacques Lacan was a French psychoanalyst who picked up Freud’s ideas about how human consciousness develops (such as the Oedipus analogy) and reformed them into a much more complex system. Why bother with it? Well, because a great deal of film theory already does.

Lacan, rather than Freud, was in vogue in the 1960s and 1970s, during the formative stage of much modern film theory. If you read classic film theory from that period, you almost certainly come across Lacan or his ideas. These discussions become incredibly annoying unless you can grasp the basics beforehand.

You can probably see some tempting connections to draw between Lacan’s notion of the imaginary and the experience of cinema. Christian Metz (see ‘Sampling film semiotics: Metz’ earlier in this chapter) is responsible for opening this particular can of worms:

- Metz drew on Lacan’s notion of the mirror phase with one important qualification: what you see in the mirror isn’t yourself but an idealised notion of what you may be. As a baby, you can’t yet control your own body. So the image is a fiction, and babies soon realise and accept that images are different to themselves.

- Metz proposed that the cinema screen operates as a kind of mirror, reflecting idealised versions of yourself. This idea is one possible explanation for the process of identification with fictional characters that you experience when involved with a film.

- Alternatively, Metz suggested that you identify not only with people on screen, but also with the cinematic apparatus itself. Sitting in the cinema watching a film, you feel as if you somehow create the images on screen, functioning as camera and projector. Yet you also know that this is an illusion, just like babies misrecognising themselves in mirrors.

All these ideas may sound sweet and innocent – babies and mirrors, how adorable! But don’t worry, Lacan also gives plenty of messy ideas about sex and death to come to terms with. He follows Freud by discussing the Oedipus complex as the encounter with sexual difference that turns you into an adult. Lacan states that after you make it through this stage, you’re forever in a state of lack, wanting subconsciously to go back to being baby, united with your mother’s body. This impossible desire defines your entire life, leading you into relationships that can never fully satisfy. Cheery, huh? But just think about Hollywood’s version of romance – such as Jerry Maguire proclaiming ‘You complete me!’ in the 1996 film named after him – and tell me that Lacan doesn’t have a point. Even if it’s buried beneath layers of interminable psychobabble.

Rejecting the male gaze: Mulvey

The pleasure of the male gaze comprises two elements:

- Scopophilia: The pleasure of looking at a sexual object, which according to Freud is associated with power, because doing so subjects the object to a controlling gaze.

- Narcissism: The pleasure of looking at an image of oneself, drawing on Lacan’s mirror stage (see the preceding section) to imply identification between male audience members and male characters on screen.

These two looks are magnified as men in the audience look at men on screen looking at women.

But here’s a twist in the tale for the male bearer of the look. The image of the woman being looked at means sexual difference, which creates a primal fear in the male viewer – that of castration. No, seriously. Fear of castration is a big deal in psychoanalytic theory. It’s important because the castration fear helps to explain the common and unsettling link between sex and violence on cinema screens, such as in slasher movies. Even if this fear doesn’t manifest in real violence, it can justify the narrative ‘punishment’ of sexuality that crops up in most films noir, where the femme fatale has to die. Alternatively, women are fetishised and turned into abstract objects, for example in those famous Busby Berkeley dance routines of the 1930s.

As the saying goes, nothing good ever comes easy. Film theory can be difficult, but if you really want to understand how movies work, the effort is well worthwhile. Film theory aims to help answer the seriously big questions of film studies, such as: why do you enjoy watching films? Does a film reflect the culture that creates it – or does it help to shape that culture?

As the saying goes, nothing good ever comes easy. Film theory can be difficult, but if you really want to understand how movies work, the effort is well worthwhile. Film theory aims to help answer the seriously big questions of film studies, such as: why do you enjoy watching films? Does a film reflect the culture that creates it – or does it help to shape that culture? Few examples of defamiliarisation beat the opening sequence of Blue Velvet (1986), which features a clear blue sky before gently panning down to reveal crimson red roses and a white picket fence. Bobby Vinton croons ‘Blue Velvet’ on the soundtrack as happy firemen wave, children cross wide streets and a middle-aged man waters his garden with a hose: the perfect picture of sunny suburbia. But then … the man clutches his neck in agony before collapsing on the grass. His dog plays with the spraying hose regardless. The camera gets closer to the grass until you see an extreme close-up of beetles and insects living off garden decay. From familiar to defamiliarised in just a few shots – that’s David Lynch.

Few examples of defamiliarisation beat the opening sequence of Blue Velvet (1986), which features a clear blue sky before gently panning down to reveal crimson red roses and a white picket fence. Bobby Vinton croons ‘Blue Velvet’ on the soundtrack as happy firemen wave, children cross wide streets and a middle-aged man waters his garden with a hose: the perfect picture of sunny suburbia. But then … the man clutches his neck in agony before collapsing on the grass. His dog plays with the spraying hose regardless. The camera gets closer to the grass until you see an extreme close-up of beetles and insects living off garden decay. From familiar to defamiliarised in just a few shots – that’s David Lynch. So you can think through your responses in relation to Stuart Hall’s reading strategies – or follow Bourdieu and consider your levels of cultural capital at different points in your life.

So you can think through your responses in relation to Stuart Hall’s reading strategies – or follow Bourdieu and consider your levels of cultural capital at different points in your life.