What is editing?

Now that you have media clips gathered in the project tab of your Browser window, what do you do with them? Edit, of course. But what is editing? Most good editors will tell you that it is telling a story with a series of images and sounds. This is certainly correct. Editing means being able to take isolated pieces of media and arrange them to communicate an idea. That is the gratifying and artistic part of the process.

But there is a technical aspect to editing that has more to do with the tools and less to do with your message. Video Editing is the process of modifying and arranging video and audio resources so that they play back in the linear order you desire. The flexibility and functionality of the tool you use to accomplish this really defines how easy it is to achieve that goal. And there are some fairly standard tools among nonlinear editors for accomplishing this.

Final Cut Pro is a very flexible editing application. It is open-ended enough to allow for many different editing styles. Your own working style will ultimately develop as you get used to the different tools available to you within the Final Cut Pro interface. Unlike the project setup process, which is very rigid and defined by the specific hardware and software configuration you work with, your editing style depends on how you feel most comfortable working and the type of projects you work on.

As we saw earlier, the various windows in Final Cut Pro are linked together based on the media passing through them. We load clips into the Viewer window to manipulate them prior to editing them into a sequence. The Canvas displays what is currently active in the Timeline. And the Timeline is the linear window, displaying the order of clips as they are played back. But this is only one way to view the usefulness of these windows.

The Timeline window is not only useful for arranging the horizontal linear order of clips, it can also be used to stack many vertical layers of video. We can thus control exactly which layer is seen and how much of each layer is seen, much as with the Photoshop layers discussed in the preceding chapter, but over time rather than as a still image. Clips can be loaded into the Viewer window for further manipulation directly from the sequence in the Timeline instead of being loaded from the project tab in the Browser window. You can trim or cut the length of a clip from directly where it sits in the sequence rather than trimming it in the Viewer. The Viewer can do more than simply load and manipulate clips from the project tab and the sequence. You can load up whole sequences as if they were individual clips and manipulate them as well. It will be up to the individual editor to become adept at fully utilizing the many possible methods of completing an edit. Let’s step through the process of building a first, simple edit.

Working in the Viewer window

The Viewer window

Editing is a process of arranging pieces of media so that they can be replayed in a particular order. To perform such an action, each media clip must be prepared based on two editing decisions: the clip duration (how short or long each clip will be in the sequence), and the edit type (how the incoming clip will meet the clip occurring before it and after it in the sequence).

Determining the duration of a clip is initially performed in the Viewer by setting In and Out points. When you originally captured the clip, you gave it In and Out points, but they were probably rough decisions. You will want to trim frames away and adjust the clip’s duration before you put it into the sequence. The beauty of a nonlinear editor is that such actions are very simple. Since we are dealing with a clip, we can put In and Out points wherever we want, or change them later on a whim if they don’t suit us.

STEP 1

Double-click one of your captured clips in the Project tab to load it into the Viewer. You will be happy to find that the playback controls of the Viewer utilize the exact same conventions as the Log and Capture window. The Viewer window, and all other windows in the Final Cut Pro interface, use the same keyboard navigation conventions (J-K-L, I, O, and Right and Left Arrow keys), even though they are playing back clips that exist on a hard drive rather than on an external tape.

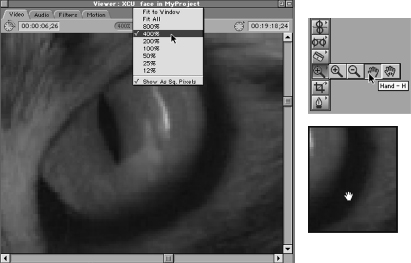

As with the Log and Capture window, the top left timecode field displays the duration of the clip loaded into the Viewer. The top right-hand field displays the frame the playhead is currently parked on in the clip. Below the Viewer’s video window, you will see that there are no timecode fields for In and Out points, which have been replaced by a few buttons as described next.

Match Frame button

The first button on the left is the Match Frame button (Figure 5-1). If a clip loaded into the Viewer window is already being used somewhere in a sequence, the Match Frame button will call up the sequence in the Canvas and Timeline windows, and it will place the sequence playhead on the same frame of the clip in the sequence that the playhead is parked on in the clip in the Viewer window. It is used for quickly finding the exact same frame that is being used elsewhere in a project. This is an invaluable tool if you want to make sure you are not accidentally reusing footage. You will find that there is also a similar Match Frame command for the sequence that allows you to call up a clip in the Viewer.

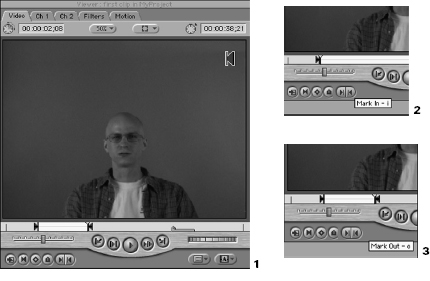

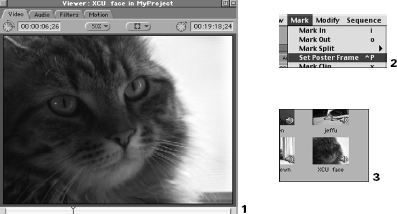

Mark Clip button

The next button, the Mark Clip button, is like a quick reset button for In and Out points in the clip (Figure 5-2). Clicking it immediately places In and Out points at the beginning and end of the clip. If you want to quickly clear the In and Out points you have already placed in the clip, or if you know that you want them to encompass the entire clip, click this button. You will see two sideways triangles appear in the clip’s timeline area defining the duration of the portion of the clip to be used in an edit.

Of course these points are totally malleable, and setting them is as temporary as you want it to be. You can grab the points themselves and move them manually, set them using the In and Out point commands to be described in a moment, or simply Mark Clip them back to the beginning and end limits of the media file associated with the clip.

Add Keyframe button

Add Keyframe, the next button, allows you to quickly manipulate the clip’s physical attributes that are located in the Motion tab of the Viewer window (Figure 5-3). It’s simply a shortcut for defining a change in the way the clip’s video and audio is displayed or heard. Keyframing will be addressed in more detail in the chapter on Compositing and Special Effects.

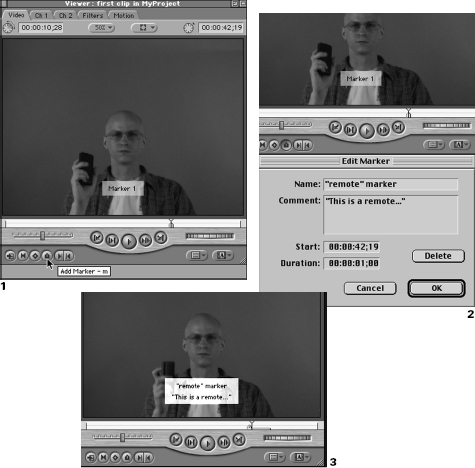

Add Marker button

Add a Marker applies a Marker to the frame on which the Viewer playhead is currently parked (Figure 5-4). Markers are very useful tools for editors. Although they do not affect playback at all and are visible only to the editor of the clip in the Viewer window, Markers allow you to insert detailed information about a frame or entire sections of your clip. Do not confuse the Markers with the Mark Clip button. Mark Clip addresses In and Out editing points for the clip, while Markers are just accessory information about the clip that is linked to a frame or range of frames.

Click this button to add a Marker to the clip loaded in the Viewer window. Then, making sure that you see the word Marker 1 in the video window, press the M key (if you do not see the Marker 1 in the Viewer’s video window, move the playhead around the Marker point in the Viewer playhead timeline until you see it). This brings up the Edit Marker dialog box.

STEP 3

Here in the Edit Marker dialog box, you can rename the Marker anything you want, type a message about the area covered by the Marker, and give it a duration so that the details of the Marker can be clearly linked to more than one frame. All this information will be displayed in the Viewer window whenever the Viewer playhead is in the Markered area of the clip. Best of all, the Marker does not affect your edit at all. It only provides another means of adding information about the clip so that you can be better organized.

Adding Markers to clips is especially useful when two or more editors collaborate on a project. Since they may not be working at the same time, it’s often critical to leave notes about specific footage that cannot be missed as the editing process moves forward. Markers, it will be recalled from the last chapter, can also be set in the clip during the Log and Capture process. Those Markers will still exist within the clip after capture, being available to the editor long after the process of logging is completed. This is an excellent way for producers to communicate their desires for a clip’s manipulation to the editor, who may start working on a project long after the producer has become unavailable for questioning.

In and Out Point buttons

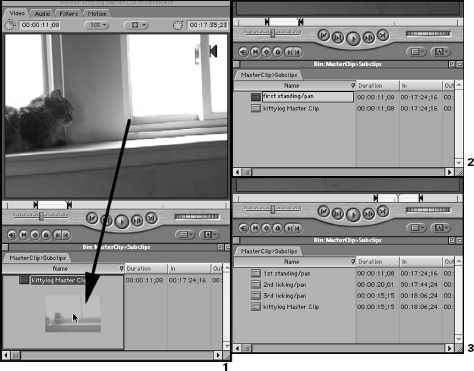

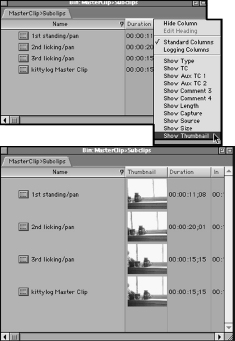

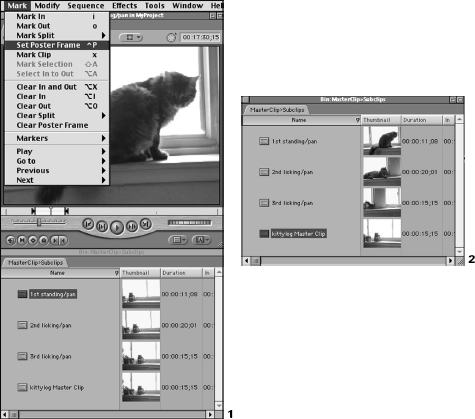

The remaining two buttons here are the In and Out points for the clips (Figure 5-5). The In and Out points will determine the first and last frame from this original, or Master clip, that will be used when the clip is edited into the sequence. The idea of Master clip and subclips is important here. The clip you load into the Viewer window from the Project tab is what is referred to as a Master clip. The Master clip is the original clip brought into the project that contains all the footage you choose your edits from. It likely contains far too much footage and must be whittled down using In and Out points before moving to the sequence.

A funny thing happens, though, once this Master clip is dragged from the Viewer window to the sequence. Instead of the Master clip itself appearing in the sequence, a subclip, or an edited and shortened version of the Master clip, is created in the sequence. This subclip is exactly like the Master clip in the Viewer it was created from, with one exception. When you load the Master clip into the Viewer window, you see all the frames of the clip, regardless of where the In and Out points are positioned. But the new subclip in the sequence uses the In and Out points you applied in the Viewer to determine the beginning and end of the clip on the sequence.

The Master clips and subclips used here should not be confused with the Final Cut Pro Subclip, which is a special command to be discussed later. The use of Master and subclip here is standard usage for describing the way that any nonlinear editing systems relate an initially captured clip to subsequently edited versions of that clip. The reason for belaboring the point is to make the reader aware that the clip edited into the sequence is not the same clip as the one in the Project tab or the Viewer, although they relate back to the same media file on the media drive. You can create as many subclips from a Master clip as you wish, and indeed you do so each time you drag a Master clip from the Viewer window into a sequence.

Remember that the Log and Capture keyboard conventions apply in the Viewer window as well, so use the I and O keys to set the clip’s In and Out points and the J-K-L keys to shuttle around the clip quickly. Hitting an In or Out point clears the previously selected In or Out point, so you can constantly reset them to your heart’s desire.

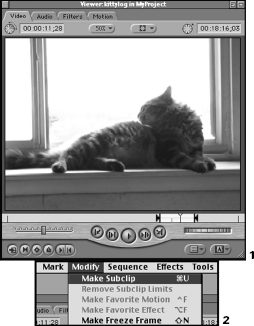

Drag and Drop to the Sequence: Insert and Overwrite

Once you have selected a new In and Out point for the Viewer window clip, it’s time to edit it into your sequence. There are a couple of ways to do this, and the best way really depends not only on how you like to edit but what sort of project you are working on. Once you master the two main methods, you’ll be able to judge which is best suited to any particular situation.

The first and most basic method is to simply drag the clip from the Viewer video window into the sequence in the Timeline window.

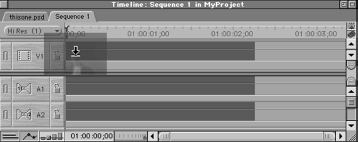

STEP 4

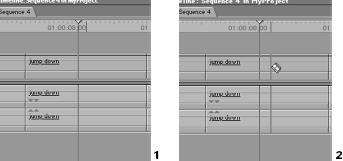

Click in the video window of the Viewer, and drag the clip down to the sequence without releasing the mouse button (Figure 5-6). Keep the mouse button pressed as you move it around the sequence, and watch the mouse pointer change shape as the sequence prepares to receive the clip.

As you drag the clip around the sequence Timeline, a ghost of each of the clip’s video and audio tracks appears there, showing you which sequence tracks the clip will be dropped into if you let go. Notice that the ghost clip may also appear to sit outside the visible tracks in the sequence. This is because Final Cut Pro will allow you to drop the clips where a new video or audio track should be, and then it will automatically create the new track to accommodate it.

STEP 5

Continue to hold the ghost clip so that it appears to sit in Video 1 and its audio tracks sit in Audio 1 and 2. Move the mouse pointer around the base line of the tracks in the sequence, and pay close attention as its shape changes (Figure 5-7).

Notice that depending on where in the sequence track you hold the ghost clip, the mouse pointer sometimes appears as a white arrow pointing either down or to the right and down. This indicates whether the edit you accomplish here will be an Overwrite or an Insert edit. Insert and Overwrite are the two most basic edit actions in a nonlinear system.

An Insert edit, represented by the “right and down arrow” mouse pointer, neatly slips your clip into a sequence. If the sequence already contains clips, Inserting will move all those occurring after the edit In point (the frame where the sequence playhead is parked) over to make room. If the sequence playhead was parked on a frame in the middle of a clip, that clip will be split into two sections, and the section of the clip after the playhead position will be moved to the right to make space for the incoming Inserted clip. No frames or clips are removed from the sequence; clips occurring after the edit In point are merely moved further down the Timeline.

An Overwrite edit, represented by the “down arrow” mouse pointer, lays the clip down wherever you drop it in the sequence regardless of what is currently sitting on the Timeline. If any clips occupy an area of the sequence where the incoming clip will sit, it overwrites them. Unlike the Insert edit, which maintained the same clips in the sequence by moving them out of the way, the Overwrite edit deletes any frames of any clips in the sequence that it encounters.

The fundamental difference is that Insert editing changes the duration of the sequence. Since the new clip moves everything over to the right and adds its duration to the sequence’s total duration, the result is more footage in the sequence Timeline. Overwrite, on the other hand, keeps the duration of the sequence exactly the same, since it is replacing whatever clip it overwrites with itself. No clips are moved over to compensate, and the duration stays the same unless the overwrite clip extends beyond the clips it is overwriting. These two types of editing require more than one clip to highlight the difference between them.

STEP 6

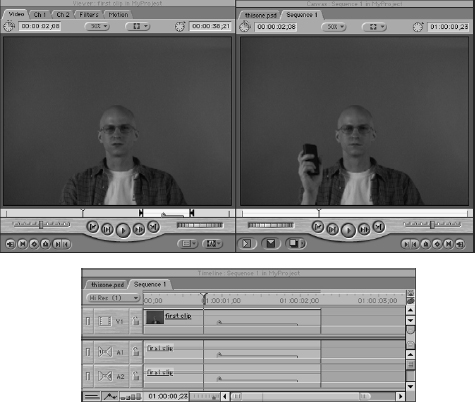

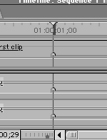

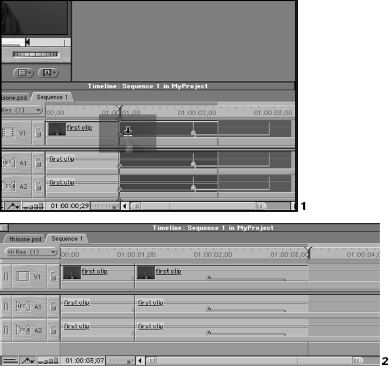

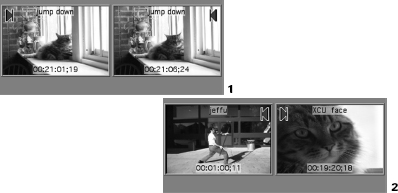

Using either the Insert or the Overwrite arrow, drop the clip you dragged from the Viewer window onto the first frame at the beginning of the sequence so that there is only one clip in the sequence (Figure 5-8). If there are no clips present in the sequence, the effect of Insert and Overwrite is exactly the same, since there is no clip to overwrite or insert into.

Notice that the clip, once dropped in the sequence Timeline, appears in the Canvas window (Figure 5-9). Wherever the playhead is moved to in the sequence Timeline, the playhead in the Canvas moves there as well; conversely, when you click and drag the playhead in the Canvas, the playhead in the sequence Timeline moves around, mirroring the action in the other window. We say that the Canvas window is a video preview of the sequence in the Timeline window.

For this example, we will edit in the same clip already loaded into the Viewer window, although you could load another clip and set In and Out points for it just as easily. Until you close the Viewer window or load another clip into it, the previous clip you loaded will still be sitting there.

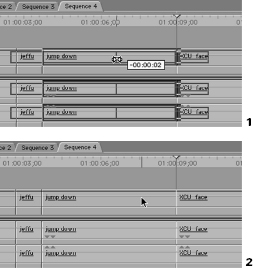

Play through the clip in the sequence and park the playhead on a frame somewhere halfway through the clip (Figure 5-10). The position of the playhead will be parked on the target frame we intend to drag the new incoming clip to in the sequence.

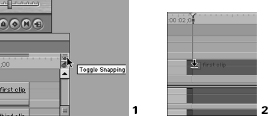

Return to the Viewer window where your previous clip is still loaded. Once again, click and drag the clip from the video window and move it down to the sequence without releasing the mouse button. When you bring the ghost clip down to the area where you previously parked the playhead in the first clip, the mouse pointer will snap to the playhead in the sequence timeline (if the clip does not snap to the playhead in the sequence window, hit the N key to enable Snapping, which may have been disabled. The Snapping feature will be more thoroughly described further on in the chapter.)

STEP 9

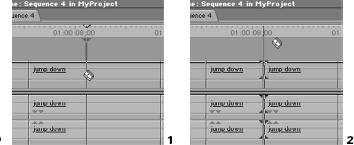

As you move the mouse pointer around this area, you will see the Insert/Overwrite arrows appear (Figure 5-11). When the arrow is pointing to the right and down indicating an Insert edit, let go of the mouse button to perform the edit.

You will see that the first clip was split in two and that the second incoming clip was inserted into the newly created gap between the first and second half of the initial clip. No footage was removed from the sequence; footage after the playhead was moved over to create the space necessary to insert the incoming video clip.

Hit Command-Z to undo the Insert edit from Step 9 so that you are once again looking at a single clip on the sequence Timeline. You can always quickly undo the last action performed by hitting the Command-Z shortcut. Once again, play through the clip in the sequence and park the playhead on a frame somewhere halfway through the clip. Now perform the same action again, but this time, perform an Overwrite edit by letting go of the mouse button when the arrow is pointing down.

STEP 10

Return to the Viewer window where the previous clip is still loaded (Figure 5-12). Click and drag the clip from the video window and move it down to the sequence without releasing the mouse button. When you bring the ghost clip down and it snaps to the playhead on the sequence Timeline, you will see the Insert/Overwrite arrows appear again. When the arrow is pointing directly down, let go of the mouse button to perform an Overwrite edit.

Instead of splitting the clip in half, moving the remaining footage over and inserting the incoming clip, Final Cut Pro simply lays down the second clip in the place of whatever was after the playhead position. It overwrites any footage that lies in the path of the incoming video clip.

Drag and drop to the Canvas: Insert and Overwrite with a Transition

There is another way to perform Insert and Overwrite edits, this time with the option of adding another important element, the Transition. Instead of dragging the clip from the Viewer window directly to the sequence Timeline, we will use the Canvas window. As we perform the edit using the Canvas, we will also address the second important issue in the process of editing: how we will have the clips cut from one clip to the next in the sequence.

We use the venerable old tape-editing terms straight-cut editing and A-B roll editing to describe the two primarily different ways of getting from one clip to the next in a sequence. Straight-cut editing means that when the playhead reaches the end of the first clip, it immediately cuts to the second clip. There is no transitional area in which both clips are simultaneously in view, and clips do not overlap or fade into one another. One clip stops on one frame and another one starts on the very next frame.

A-B roll editing allows for a different sort of cut between clips called a Transition. A Transition is a juncture between two clips. But unlike the straight-cut juncture, which allows no overlapping, the transition lets us see a portion of both the outgoing and the incoming clip simultaneously. This can be a Dissolve, in which the outgoing clip fades out and the incoming clip materializes. It can be a Wipe, in which a line crosses the screen covering the outgoing clip and revealing the incoming clip. It can be any number of stylistic effects, but the main point is that the two clips are both seen simultaneously for the duration of the transition.

The transition originated in the old film and video tape-based editing systems with a mixing system called A-B Roll editing. With film, an optical printing process was used to mix an outgoing and incoming edit. To perform video A-B Roll editing, you need to have three decks. The first two decks, A and B, contain the outgoing and incoming clip footage respectively that is being edited onto the third deck, the edit (or record) deck. A video mixer lies between A and B decks and the edit deck. The video mixer takes video sources A and B and mixes them together in whichever transition was required as they pass out to the edit deck. A transition from clip A to clip B is performed by mixing out clip A and mixing in Clip B during a short period in the recording. Once the transition is complete, clip A is no longer playing and clip B is being recorded.

The editor decides where the transition should occur and then uses the video mixer to switch from source A to source B, using one or another of the many possible transitions. Which transition is used and how long the transition takes depend on the editor, as does the length of the overlap between the two clips being transitioned. Although the term A-B Roll isn’t common any more outside of expensive online tape editing suites, the process of transitioning between clips on the sequence is essentially handled the same way. The A and B decks correspond to the first and second clip that we want a transition to separate in our sequence. As we pass out of clip A, we want to transition into clip B.

There are two things to remember about the A-B Roll editing example. First, there was a video mixer involved in the A-B roll example; second, there was an overlap between the two video clips in order to perform the transition. The mixer from our example will be the transition that we apply to the cut where the two clips abut. And the overlap that is required will be the extra, unused footage that lies beyond the In and Out points of the clips we edited into the sequence. Since the transition requires overlap area between the two clips, you need to make sure there is trimmed footage that the transition can access from beyond the In and Out points of each clip. The extra footage on either side of the In and Out points of the clip is the handles you were just being recommended to capture with your clips.

Once again, we take advantage of Final Cut Pro’s drag and drop technique to create this transition.

STEP 11

On the sequence, move the playhead a little further down to an area where there are presently no clips. Now go back to the Viewer window where your clip is still loaded. This time, create new In and Out points, making sure that there are at least 30 frames between the beginning of the Master clip’s media and the In point you apply to it. Likewise, make sure that there are at least 30 frames between the end of the Master clip’s media and the Out point you apply.

These 30 frame handles on either side of the In and Out points will provide plenty of overlap frames for our transition. The overlap space for each clip is the footage that lies before the In point or after the Out point of the clip.

STEP 12

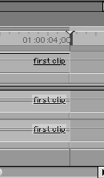

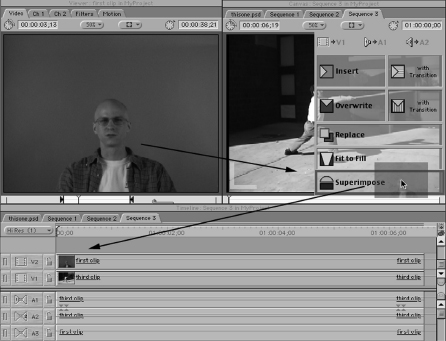

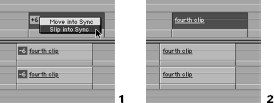

Click the clip in the Viewer video window and this time drag it into the video window of the Canvas without releasing the mouse button (Figure 5-13). As you hold it over the Canvas, you will see overlay windows appear offering the choice of Insert, Overwrite, Replace, Fit to Fill, and Superimpose. In addition, the Insert and Overwrite areas will have an optional extra window for including a transition.

Because there is currently no video clip in the sequence, we could choose either Insert or Overwrite with equal results. You will perform the exact same edit as you did when dragging directly to the sequence earlier. This time, however, instead of determining the frame to edit into the sequence with the mouse pointer, you will simply edit to the place where the sequence playhead is currently parked.

STEP 13

Hold the clip over either Insert or Overwrite (do not choose the transition option just yet), and you will see the choice highlighted. Release the mouse button, and you will see the clip appear on the sequence exactly where the playhead was parked.

STEP 14

To add the second clip with a transition, first make sure that the playhead is parked at the end of the clip you just inserted into the sequence (Figure 5-14). When you edit a clip into a sequence, the playhead immediately moves to the last frame of the incoming clip, since it assumes your next edit will follow that clip. If the playhead has been moved, drag it back over to the end of the clip you just added to the sequence, making sure that it is on, not following, the last frame of the clip.

Transitions, such as the default Cross Dissolve that we are about to use, are difficult to see if the clip being transitioned to is very similar to the clip being transitioned from. Since the Cross Dissolve fades from one clip to the next, you might not even be able to see the transition. For this reason, pick a new clip from your Project tab that looks substantially different from the clip you have just edited into the sequence.

STEP 15

Double-click another clip in the Project tab to load it into the Viewer window. Once again, set In and Out points, making sure that you leave at least 30 frames on either side of the In point and the Out point to provide adequate overlap space for the transition.

STEP 16

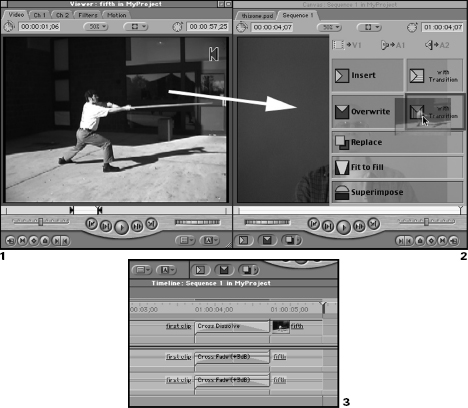

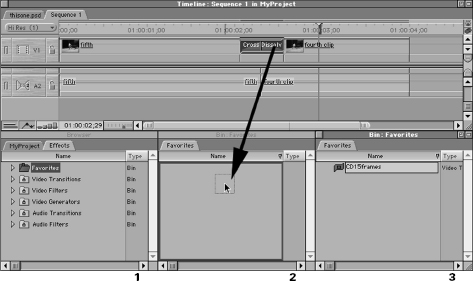

Pick up the clip in the Viewer window and drag it into the Canvas window, this time releasing it as it hovers over the Overwrite with Transition area (Figure 5-15). Instantly, the clip appears on the sequence following the first clip, but this time there is a small gray patch connecting the two.

The small gray patch between the two clips is the Transition. It is an area in which footage from both clips is present, although it is actually composed of footage that exists beyond the previously established In or Out points of the clips. In this nonlinear system, Final Cut Pro can reach back into the media file associated with your clip when it needs more footage as long as there is more footage in the clip’s media file to access. The benefits of adding frame handles in the capture process of the last chapter become more obvious now that footage beyond our In and Out points becomes valuable as transition overlap footage.

If you receive a message stating “Insufficient Content for Edit,” it means that you do not have enough footage beyond the In or Out point of either one or both of the clips for Final Cut Pro to create the transition. Remember that an overlap of footage means that both clips must have at least some footage outside the In and Out points. Although the number of frames outside the In and Out points does not have to be equal, it does have to exist.

By default, this transition is a Cross Dissolve, which will fade one clip out and the other in over the length of the transition. You can change the default transition to something you use more frequently, or choose any other transition available to replace the Cross Dissolve after it has been applied.

After applying the transition, place the sequence playhead directly in the center of the transition (Figure 5-16). You will be able to see both the first and second clips at half their opacity or visual strength, since one is fading out and the other is fading in. If you try to play this short sequence back, you will probably notice that when the playhead crosses the transition, the footage disappears and the word Unrendered appears. Once the playhead is past the transition, the video footage appears again. This is because transitions must be rendered to be played back correctly.

The reason that your normal captured footage can be played back without rendering is because the footage exists on your hard drive as captured media. There is media that the clip is related to. When the playhead encounters the clip, the media is accessed and the video plays back. But the transition is different. There is no media clip yet that corresponds to the dissolve between the two clips. Final Cut Pro knows that the transition footage needs to be created or rendered to be played back correctly, so it warns you that the material is unrendered with this message.

Any footage in a sequence that must be rendered will have a red bar over it in the Timeline window (Figure 5-17). The red bar indicates that render files have not been created for the clip and that it will not be displayed properly upon playback. Anytime you see this red bar, it means that there is an effect of some sort—a Motion tab effect, an Effects filter, or a Transition that must be rendered. The only exception to this is if your Preferences and/or Audio/Video Settings have been incorrectly configured, in which case your captured footage will likely display the red bar as well. In those instances, do not render; go back and fix your settings!

STEP 17

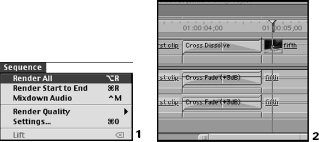

Rendering the transition is simple. Make sure the Timeline window is active, then go to the Sequence drop-down menu and select Render All (Figure 5-18). There are other choices available for rendering in this drop-down menu. What choices are available depends on what clips, if any, are selected on the sequence Timeline. If an individual clip or transition is selected, you can choose Render Selection to avoid rendering all clips or transitions you may not be presently concerned with. If no clips or transitions are selected, then Render Selection will render all clips in the sequence.

A render progress bar will come up showing you where the rendering process is. After the render is complete, the red bar will be replaced by a barely perceptible light gray bar, indicating that the material has been rendered. Go back to the sequence and play through the transition. You will now see the dissolve properly played back.

Of course you are not limited to the way this dissolve performs. You are looking at the default settings for the Cross Dissolve transition. You can easily change the parameters of the transition itself, being limited only by the number of overlap frames available past the In or Out points of either the outgoing or the incoming clip.

STEP 18

To change the parameters of the transition, go to the sequence and double-click on the gray transition itself (Figure 5-19). Make sure that you click on the gray transition and not the cut, or edit point, between the two clips (if a Trim Edit double video window appears, close it and try again). When you successfully double-click on the transition, it will load up in the Viewer window, as if the transition were a clip, but with a control tab for the transition itself.

When the transition is loaded into the Viewer window, you can adjust how long the transition lasts, where the middle point of transition occurs, and many other factors that depend on the type of transition you have created. You will see that as you adjust the parameters in the Viewer window the transition in the sequence is updated. You will also see that the red render bar has returned, because the render files you created no longer reflect what the transition does. To view the new transition parameters, you will need to render again.

Drag-and-drop transitions

The method discussed in the preceding text is not the only way to apply a transition to two abutting clips. There is yet another simple drag-and drop technique for applying transitions.

STEP 19

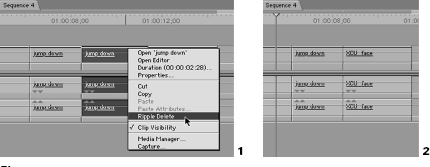

Clear off the sequence by activating the Timeline window, clicking on the dark gray area of the sequence Timeline and clicking and dragging through the clips with the mouse button pressed (Figure 5-20). This action is called a marquee selection. You will notice that each clip marqueed this way turns brown, indicating that the clip was selected.

You can also quickly select more than one clip by clicking on clips with the Shift key depressed (i.e., Shift-clicking). As you Shift-click more clips, they all stay selected, whereas if you were not Shift-clicking, selecting one clip would deselect the previously selected clip(s). Shift-clicking changes the selection status of a single clip without changing the selection status of other clips. To deselect an individual clip while Shift-clicking clips, simply Shift-click the clip again to remove it from the group of selected clips.

STEP 20

Once all the clips in the sequence have been selected, hit the Delete key to remove them from the sequence. When the sequence is again empty, quickly perform two Overwrite edits into the sequence so that two clips are abutted with no transition but have the previously described overlap frames on either side of their In and Out points.

STEP 21

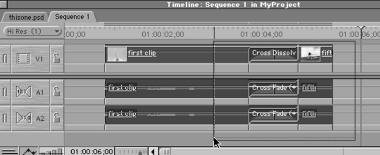

Go to the Browser window and select the Effects tab. Double-click the bin named Video Transitions (Figure 5-21). Inside the Video Transitions bin that opens up, double-click the Dissolve bin. Inside the Dissolve bin, click the Cross Dissolve icon and drag it over onto the cut between the two clips you just edited into the sequence. When released onto the edit point between the two clips, the transition will pop right in, just as if you had applied it from the Canvas.

STEP 22

Double-click the gray transition you just dropped onto the edit point between the clips so that it loads into the Viewer window. Once again, adjust the various parameters of the transition until you are satisfied with the results. Click on the Timeline window again, hit Command-R (the keyboard shortcut for Render Selection) and after the brief render process, play the transition back.

Using the drag-and-drop method of applying transitions to edit points between clips, you can select any of the available transitions in the Video Transitions bin of the Effects tab.

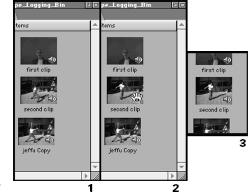

Creating customized transition favorites

Once you have adjusted the parameters of a transition the way you want them, you can save a new version of the transition that retains the parameters you have changed for quick access in the future. Instead of having to change the parameters for a transition every time you use it, you will make a copy of the transition you have customized and apply that instead of the default one you started with. This is called creating a Favorite.

As an example, let’s say that you prefer for your Cross Dissolve to last for 15 frames instead of the full one second that the default Cross Dissolve transition is set to last.

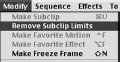

STEP 23

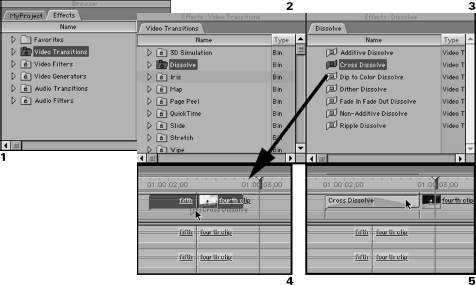

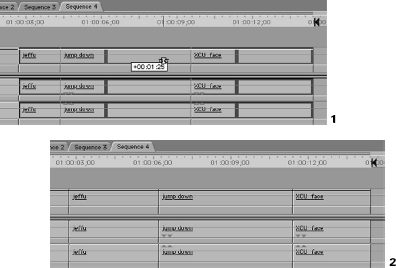

In the sequence, double-click on the transition so that it loads into the Viewer window (Figure 5-22). In the timecode field to the upper left of the window, change the value from 00:00:01:00, or 1 second (29.97 frames for NTSC and 25 for PAL), to 00:00:00:15, or fifteen frames. The transition will automatically shrink both in the Viewer and in the sequence.

Now that the transition in the sequence has a new customized parameter that differs from the one in the Video Transitions bin, we will create a Favorite of it.

STEP 24

Double-click the Favorites bin in the Effects tab of the Browser window so that it opens up (Figure 5-23). Go back to the sequence, grab the gray transition, and drag it to the opened Favorites bin.

STEP 25

A new Cross Dissolve transition bearing the parameters you changed is in the Favorites bin. Although it is still named Cross Dissolve, it actually has a different length than the Cross Dissolve you originally pulled from the Video Transitions bin. Before you can confuse one for the other, click on the name of the Cross Dissolve transition in the Favorites bin to highlight it. Type in the new name “CD15frames” to distinguish it from the original Cross Dissolve or any further variations of the Cross Dissolve transition you may create as Favorites.

Now whenever you wish to apply a 15-frame Cross Dissolve, you can simply drag this transition from the Favorites bin and apply it. The transition will also be available from the Effects drop-down menu under the heading Favorites (Figure 5-24). You can make this transition the default for use in applying transitions from the Canvas as we did earlier in this lesson by selecting your “CD15frames” transition in the Favorites bin and choosing Set Default in the Effects drop-down menu.

You could also have placed the transition on the edit point by moving the playhead in the sequence to the point between the clips and going to the Effects drop-down menu. There, under the Video Transitions submenu, you will find all the Final Cut Pro transitions available to you. The Effects drop-down menu is your access menu for many other effects to be described later in the Compositing and Special Effects chapter.

If it seems arbitrary to have waited until this point to describe the drop-down menu items for performing transitions and effects, there is a reason. Your speed and agility within Final Cut Pro, as well as other production applications, greatly depends on your ability to use the interface of the application directly rather than hunting through menu items one by one to find what you are looking for. The risk of carpal tunnel syndrome is another reason for avoiding the repetitive action of pulling down drop-down menus. Learning the keyboard shortcuts for actions and using the mouse only for things like dragging clips around will save your wrist a lot of work and speed up your process into the bargain.

At this point, you can bring clips into Final Cut Pro, select In and Out points for them, and get them to the sequence in the Timeline window with or without a transition. That is enough to edit with. But it implies that we don’t want to change things once they make it to the sequence.

What we have done up to this point isn’t really that far removed from the process of tape editing. With tape editing, cuts follow cuts. You lay down an edit onto the edit deck, and then you lay down the next edit, possibly with a transition. You continue doing so until you complete the piece.

But that is linear editing. If you discovered that you’ve extended a clip a little too long, you have to go back through and re-edit the whole thing from the offending clip on. But we are using a nonlinear editor here, and we should take full advantage of its unique ability to alter clips from within the sequence itself, instead of simply adding edit to edit in a linear fashion.

Of course we’ve already seen a little nonlinear action with the Insert edit. With the Insert edit, we put a clip exactly where we wanted it to occur without overwriting what was already there. But we can do much more with our nonlinear editor. We can trim our clips with great precision in the sequence itself, using tools that are dedicated to helping you arrive at the most appropriate cut between any two clips that adjoin.

There are a few ways of trimming clips on the Timeline. These include directly grabbing the edge of the clip and moving its In or Out point, using the dedicated Trim Edit window, or using certain dedicated tools that live on the Toolbar. These different methods offer differing conveniences. One is less precise but easily accessible, one is more precise but must be accessed in a separate window, and another is a unique mixture of both.

The key is to master them all so that you can access each one where it becomes valuable. Only experience can instill the quick appropriate use of each one, so try them all until you get the hang of them, and then access them frequently. Trim functions often confuse new users because the relationship between clips and other clips or between clips and their media is unclear.

Trimming is not difficult however, as long as you remember that each clip on the sequence is only a small carved-out section of a larger Master clip that you originally captured or imported into the Project tab. Because it is only a section of the clip, Final Cut can easily change the In and Out points for that section on the fly without the need to revisit the Viewer window’s edit tools. As you change the In and Out points for the clip, you are only defining which section of the Master clip the smaller section in the sequence refers to. Trimming a clip that exists in a sequence does not affect the Master clip, which exists in the Project tab.

Mastery of the various Trim functions will turn your Final Cut Pro station from a nice editing package into a real professional editor. It will give you control over every aspect of the sequence and allow you the ability to make quick changes that drastically alter the nature of your production without having to rebuild entire editing structures from scratch. Trim is the secret weapon of all good editors and is an essential tool to master.

The easiest trimming technique

The simplest trim function you can perform involves trimming the In or Out point of a clip directly on the edges of the clip itself in the sequence. This trim is so basic it does not require more than one clip. You are simply changing the In or Out point for the clip based on the amount of media associated with the Master clip.

STEP 26

Start with a fresh clean sequence in the Timeline by selecting and deleting all the clips there. Insert edit a clip onto the sequence. Move the mouse pointer near either the beginning or end of the clip until you see it change from the generic Selection arrow to a vertical line with an arrow pointing in either direction (Figure 5-25). When the mouse pointer is shaped like this, it has assumed a trim function.

STEP 27

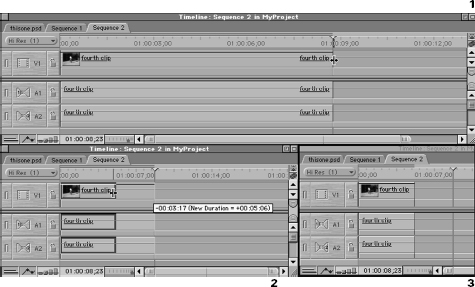

Click on the end of the clip and drag in either direction. You will see that the length of the clip adjusts following this tool. When you let go of the mouse button, the new In or Out point for the clip will stick and you will have changed the duration of the clip. Also notice that as you adjust the trim, a small text box appears next to the clip indicating the number of frames you have added or subtracted to the clip in the trim operation and the new total length of the clip measured in duration.

STEP 28

Click the clip edge again and perform the same drag motion, dragging as far to the left or the right as the tool will allow. At some point, you will reach the limit of the media file that the Master clip refers back to. Obviously, you cannot extend a clip beyond the limits of the media file or the Master clip it refers to, so this is the limit of the trim for the clip.

This tool can be very limiting for a couple of reasons. When you trim a clip, you are usually doing so to refine an edit point, something that you want to approach with precision that may require removal or addition of only a single frame. Unfortunately, this direct trimming action can be very unwieldy for precise editing. Much of the time, you will be looking at your Timeline scaled out so that you can see several seconds or even minutes at a time. In such situations, trimming a single frame using the direct method is practically impossible, like using your entire fist to dial a number on a touch-tone telephone. Although it can be done, the edit make take several hair-raising and frustrating moments, during which all your creative juices leak away.

Another problem with using the direct trimming tool is that you can trim only one end of one clip at a time. This may not seem limiting at first glance. But what if you have two clips abutted as a straight cut in a sequence and you want to take one frame away from the first and add one frame to the second? Using the direct trim method described above would require clicking on both clips, probably more than one time. And if you weren’t sure that’s what you wanted, you’d have to go back through the same motions to change it back.

More trimming precision: the Trim Edit window

Final Cut Pro has a solution for such issues. It’s called the Trim Edit window, and it is a dedicated window for allowing extreme precision in selecting the exact point at which two adjoining clips meet each other. Using the dedicated Trim Edit window, you will be able to quickly add or remove frames from the Out point of the first clip and the In point of the second clip. You will also be able to easily preview the trimmed edit from inside the window so that you can adjust it again before committing to it. And best of all, you can choose to adjust the first, the second, or both clips simultaneously. It is very flexible.

Calling up the Trim Edit Window

To use the Trim Edit window effectively, you need to have two abutting clips.

Clear off the sequence of clips using Select and Delete so that you start with a fresh sequence. Perform two edits so that you have two clips abutting on the sequence in a straight cut.

STEP 30

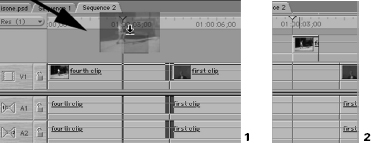

Go to the sequence and double-click the edit point between the two clips (Figure 5-26). Doing so will immediately open a large double video window called the Trim Edit window.

The two video windows of the Trim Edit window each correspond to one of the video clips; the left window is for the first or outgoing clip, and the right is for the second or incoming clip. Inside this window are all the tools you need to prepare a frame-specific edit between any two clips.

Some of the navigation tools will appear familiar, but make no mistake; this window functions according to its own rules. What you do here updates the sequence it was opened from, as one would expect. Until you are familiar with the functioning of the Trim Edit window, make sure to keep the Timeline window in view so that you can monitor the effect the Trim Edit window has on the sequence it originated from.

On the top left-hand and top right-hand corners of the Trim Edit window, you will find the familiar clip duration fields. These give the present duration of their respective clips, based on the current In and Out points of the clips in the sequence. This number does not reflect the duration of the Master clips from the Project tab that the clips from the sequence reference. The duration will change as you trim the clips using the tools in the window. The name of each clip is included for reference as well.

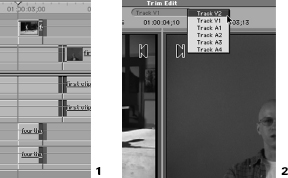

The Track drop-down bar

In the center of the top of the window is a Track drop-down bar that lets you select which video or audio tracks you are basing your trim adjustments on (Figure 5-27). You can actually apply the same trim action to more than one track at the same time, which can be a big help in keeping two or more clips equal in duration or alignment.

There are many reasons for trimming multiple edit points at once. Chances are that you will encounter situations in which you need to extend or retract the edit points for more than one clip to keep a group of clips aligned with each other. By Command-clicking the additional edit points between two abutting clips in the sequence, those edit points are added to the choices in the Track drop-down bar at the top of the Trim Edit window.

The only two restrictions on this activity are that there can be only one edit point selected per track and that the trim applied in the Trim Edit window is applied equally to all selected edit points, regardless of which edit point is selected in the Track drop-down bar. This lets you base the trim effect of many different edit points across all the video and audio tracks on how you trim one critical edit point in any one of the video or audio tracks.

STEP 31

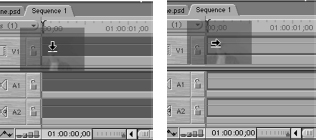

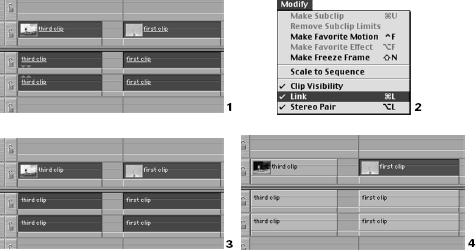

Leave the abutting video clips in the Video 1 track. Next, edit in a new clip from the Viewer window, but this time, drag it from the Viewer and drop it into the sequence in the space above the Video 1 track so that it creates a new Video 2 track (Figure 5-28). Make sure that this new clip’s edge is not vertically lined up with the edit point of the two clips you have abutted on the Video 1 track.

Single-click an edge of the clip in the Video 2 track, then Command-click the original edit point division between the other two clips in Video 1 (Figure 5-29). You will see that each edit point becomes brown as it is selected.

STEP 33

Double-click one of the two selected edit points to open up the Trim Edit window.

STEP 34

Go to the Trim Edit window that opens and click on the Track drop-down bar at the top and center of the Trim Edit window. You will see that you now have an option between using the Video 2, the Video 1, or any of the four accompanying audio tracks as the basis for the trim.

Any trimming that takes place will be applied to all the clips that are selected. And since any trim is applied to all these edit points, this also means that any clip with media file limits will limit the amount of trimming that can be applied to any of the clips. If you had more tracks and you wanted to add additional edit points to the group already selected and present in the Track drop-down bar, just Command-click to add them to the selection. But remember that you can have only one edit point selected per track.

You will also notice that as you switch between the choices in the Track drop-down bar, the timecode value just below it changes and the playhead moves from edit point to edit point in the sequence. This center value always reflects the sequence frame number that the edit point currently selected in the Track drop-down bar is positioned on. As you trim the edits, this number will likely change as you move the In and Out points back and forth.

STEP 35

Make sure that the Track drop-down bar is set on Video 1, so that there is both an outgoing (left) clip and an incoming (right) clip.

Look directly below the two video windows in the Trim Edit window to find a little timeline track containing a couple of items. The playhead of the track is a little vertical line topped with a yellow triangle. Accompanying this in the track will be an In or Out point marker, depending on the video window in question. There will be an Out point marker on the clip in the left, outgoing window and an In point marker on the right, incoming window.

STEP 36

Move the playhead around in this little timeline and you will see that it is previewing the media available for use by the clip, giving you the opportunity to quickly scan through it for the optimal new edit point. Make sure that as you move the playhead around, the mouse pointer is shaped like an arrow; otherwise, you are probably adjusting the trim. Do not touch the In or Out points just yet. Use Command-Z or undo to quickly negate an accidental trim action.

The range of frames you can preview for the new edit point is equal to the limits of the Master clip and the media file associated with the clip. The lighter area of the little timeline is the range of frames that are already in the clip in the sequence. The darker area is the range of frames that exist in the Master clip and the media file associated with the clip but are not yet included in the clip in the sequence.

Navigating the clips in the Trim Edit window

Underneath this track bar are the familiar tools for navigating around a clip (Figure 5-31). There is a Jog and a Shuttle for moving around. Predictably enough, there is J-K-L support for each separate window, although the response will not be nearly as rapid as in the Viewer or the Canvas. The Trim Edit window is best suited for precise, hair-splitting, one-frame cuts, so it is not optimized for normal playback out to video. There is also a Play button and an advance and retreat one frame button.

![]()

![]()

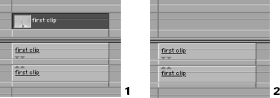

Beneath each of these video windows is an Out Shift or an In Shift button for the outgoing or incoming video windows, respectively (Figure 5-32). This button will move the Out or In point to where the playhead is parked in the Trim Edit’s little timeline. It is accompanied by a timecode value that displays how many frames the new Out or In point is from the original edit point position when the Trim Edit window was first open. Of course, this In Shift and Out Shift uses the I and O keys as keyboard shortcuts, moving the In or Out point to wherever the playhead is parked in the little timeline of the Trim Edit window, just as with the In and Out functions in the Viewer and the Log and Capture windows.

Trimming edits using this window can be done in two ways. As is usual for Final Cut Pro, there is a direct click-and-drag method and a more precise numerical entry. Care must be taken when performing the trim, though, because you have to tell Final Cut Pro which of the Incoming or Outgoing clips you want to trim, or if you want to simultaneously trim both.

It is pretty easy to identify which clip is to be affected by the trim action you initiate. Above each video window in the Trim Edit window is a long green bar. If the bar is present above a video window, trimming actions will affect the clip in that window. You can choose to have one, the other, or both clips enabled. To enable the green bar and trim actions for a clip, simply click in its video window. You will notice that clicking in one video window enables it while disabling the other. To enable both video windows so that trim actions are applied to both clips, either Shift-click the second video window or click in the thin space between the two video windows.

When you move the mouse pointer over the video windows, you’ll notice that its shape changes again. This time it appears in one of three shapes, dependent on where in the Trim Edit window you have it (Figure 5-33). If it lies in the left outgoing clip window, it appears as a little filmstrip roll with the tongue hanging out to the left. This shape, referred to as a Ripple Edit, is a metaphor for a film take-up reel. It’s called a Ripple Edit because as you trim using it, the change in duration ripples back through the rest of the sequence the trim applies to, shortening the length and eliminating the possibility of creating a gap between any of the clips. When a clip is ripple trimmed, as it is shortened or lengthened, all other clips in its track are moved over either to give it more room or to cover any gaps the trim might have created.

If the mouse pointer is lying in the right video window, predictably, the mouse pointer becomes a Ripple Edit take-up reel for the incoming video clip. It performs exactly the same function as the other Ripple Edit tool, except that it applies to the incoming clip. Once again, the tongue is hanging in the direction of the clip that will be trimmed by the tool.

The third possible shape is actually just a combination of the two and is called a roll edit. If you place the pointer between the two video windows, you will see a combination of the two Ripple Edit spools and tongues, symbolizing that the trim function will now be applied to both outgoing and incoming clips. Do not be confused though, because the roll edit actually is just moving the edit point relatively for each clip. Rather than taking away a frame from or adding a frame to each separate clip, the roll edit takes away from one clip and adds to the other. The net effect of this action is that the new edit point occurs earlier or later in both clips. The clips themselves are not moved, and the total duration is not changed, only the edit point at which one of them stops and the other starts.

The gist of this is as follows. If you want to trim frames only from or to the outgoing left clip, you click on the left video window to select the outgoing Ripple Edit. If you want to trim frames from or to the incoming right clip, click on the right video window to select the incoming Ripple Edit. If you want to trim from one clip and add to the other so that you move the edit point between the clips without moving the clips themselves, click in between the video windows and select the roll edit. You can always easily tell which window is enabled for trimming by seeing which window has the green bar on top.

There are two ways to perform the trim, one of which is imprecise, but fast, the other of which is frame-specific but much slower. After you have chosen the roll edit or either of the Ripple Edits, you will notice that clicking in the video window has no effect other than enabling that window for trimming.

STEP 37

Click on the left video window to enable the Outgoing Ripple edit (Figure 5-34). Position the mouse pointer over the Out point in the little timeline track of the left video window. Clicking on the Out point and dragging it will trim the incoming clip. Continue to drag the Ripple tool in either direction and watch the sequence Timeline update as you adjust the trim.

STEP 38

Click on the right video window to enable the Incoming Ripple edit. Position the mouse pointer over the In point in the little timeline track of the right video window. Clicking on the In point and dragging it will trim the outgoing clip. Continue to drag the Ripple tool in either direction and watch the sequence Timeline update as you adjust the trim.

Click in between the two video windows to select the Roll Edit. Position the mouse pointer over the In or the Out point in either of the two little timeline tracks. Clicking on either point and dragging it will trim both clips. Continue to drag the Roll tool in either direction and watch the sequence Timeline update as you adjust the trim.

As you trim using these tools, watch the Out Shift and In Shift numbers in the bottom left- and right-hand corners respectively to see how far you have adjusted in either direction as you drag. As you will notice, this sort of click-and-drag trimming is very imprecise. Once you’ve moved the edit point for either clip, it’s difficult to get the Out Shift and In Shift numbers back to zero such that the points are in the exact same position as they were when the Trim Edit window was opened. If you made a change to the edit points and then decided you didn’t like it, it could take you all day to get the original edit points back.

For this purpose, Final Cut Pro has a much more precise method. At the very bottom and center of the Trim Edit window, you will find four buttons with the values –5, –1, +1 and +5 (Figure 5-35). These buttons simply perform the same trimming action described previously but for the value of the button. The –1 button, for example, will move the edit point one frame to the left for either or both clips, depending on whether a Ripple or a Roll is enabled. The +1 button will move the edit point one frame in the opposite direction. The –5 and +5 buttons move the edit point even more quickly. You still need to select which side of the Trim Edit window you want to affect using these buttons if you’re not performing a Roll edit—that is, applying the trim to both sides equally.

![]()

You will in all likelihood find that using the precise buttons is easier and faster than the click-and-drag technique. Since it’s pretty easy to count as you mouse-click, you can always quickly click in corrections without having to struggle and wear your wrist out. To make things even easier, there is a keyboard shortcut for these precise trim buttons. The [ and ] keys correspond to the –1 and +1 buttons. Shift-[ and Shift-] correspond to the –5 and +5 buttons. You can actually customize the number of frames that appear in the –5 and +5 buttons by setting a value higher or lower in the Multi-Frame Trim Size field in the General tab in the Final Cut Pro Preferences.

Previewing the trim before leaving the Trim Edit window

Finally, there are a few buttons for previewing your edit before leaving the Trim Edit window. Remember that when you close this window, the Out Shift and In Shift values will reset. Once the In or Out Shift value is gone, it can be difficult to get your edit point back to where it was before you changed it. If you catch a mistake before leaving the window, it’s easy to make the adjustment based on the number of frames that the new edit points have shifted from what they were when the window opened. Previewing the edit to make sure it is what you want is a good way to avoid having to go back and piece together your previous edit points.

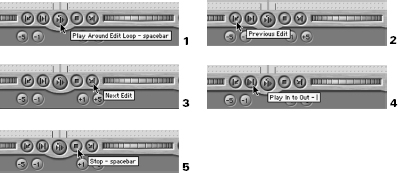

There is a tool specifically for this purpose. Just below and between the two video windows are a few play buttons (Figure 5-36). The one in the center is called Play Around Edit Loop. When you press this button, Final Cut Pro previews the edit by playing from a few seconds before the edit to a few seconds after it. You actually customize the amount of Play Around either before or after the edit by changing the values for Preview Pre-Roll and Preview Post-Roll in the General tab of the Final Cut Pro Preferences.

The furthest left of the five buttons, Previous Edit, is for moving the current edit point loaded into the Trim Edit window to the previous edit. Be careful, though, because it refers to the previous edit point that occupies the same track as the current edit point. If you were looking for the previous edit point on another track, you might end up quite far from where you expected to be. The furthest right button of the five, Next Edit, performs the same function, except that it moves forward in the track rather than going in reverse.

The button just to the left of the Play Around Edit Loop is the Play In to Out. This will preview from the beginning of the outgoing left clip to the end of the incoming right clip, regardless of how your Preview Pre- and Post-Roll Preferences have been set.

The preview playback is a loop, so to stop the loop, there is a button to the right of the Play Around Edit Loop. You can also hit the Spacebar to start or stop it.

Trimming is fast and easy using the Trim Edit window. Just double-click on the edit point you want to trim in the sequence. When the Trim Edit window pops up, select which clip you want to Ripple edit, or you may choose to perform a Roll edit of both clips. Click the plus or minus frame buttons, or the [ and the ] to define the points the way you want them. Preview the cut to make sure it performs the way you want it to. Then close the window, and you’re done.

The Timeline and the Toolbar, a deadly duo

A lot of the material that has been discussed previously has been about how Final Cut Pro allows you to edit in the Timeline from other areas of the application. We created In and Out points in the Viewer window to edit clips into the sequence Timeline. We saw Insert and Overwrite editing from the Canvas window. We learned to trim our sequence’s edit points from inside the Trim Edit window. We’ll even see later on how to load up a sequence in the Viewer as if it were just another clip.

But don’t get me wrong. The sequence and the Timeline window it lives in are powerful tools. Many of the preceding trimming actions can be accomplished directly on clips within the sequence itself. It’s necessary to include the Toolbar in this discussion as well, because, with only a few exceptions, the Toolbar tools work directly within the Timeline window. Although editing on the Timeline can sometimes feel a little sloppy and imprecise, there are times when quickly grabbing a clip and nudging it into place will do the trick. It’s the editor’s job to figure out the fastest, most efficient way of working so that more thought process goes into the “why” of editing and less into the “how.”

Let’s quickly go through the Timeline window and take a closer look at its features and controls. From the top left-hand corner of the window, the tabs for the open sequences are displayed. If you have more than one open sequence, you can switch between them by clicking on their tabs. You will notice that when you switch tabs, the tab in the Canvas window switches to match. Every sequence in the Timeline has a sister tab in the Canvas window. The Canvas will always reflect what is taking place in the sequence, and until we address how Compositing and Effects work, it should be regarded as a video preview monitor for the sequence.

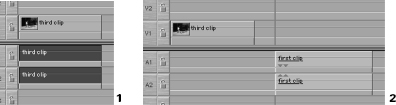

The Timeline tracks

Moving down into the Timeline itself, we find tracks (Figure 5-37). The default number of tracks when you create a new sequence was set back in the Timeline Options tab of the Preferences. Unless you changed that Preference, the default for a newly created sequence will still be one video and two audio tracks.

The video track area is separated from the audio track area by a thick gray double line. You can adjust how much of the window is dedicated to the video tracks versus the audio tracks by clicking this line and dragging it. If you have only a few tracks currently in a sequence, you won’t see much difference from moving it around. But when you have 10 tracks of video and audio, you’ll see that being able to prioritize the window for video or audio tracks will make a big difference.

As we saw in the previous section on trimming, it’s easy to create a new video or audio track in the sequence by simply dropping a clip into the space where the next video or audio track should be. When you let go of the clip, the track will be automatically created. You can also create new tracks or remove tracks you don’t want by selecting Insert Tracks or Delete Tracks respectively from the Sequence drop-down menu. You can have up to 99 tracks of video and 99 tracks of audio in any sequence.

The only serious limitation to the number of possible tracks in your project is the number of audio tracks that Final Cut Pro and your Macintosh hardware can play at once, or what is referred to as real-time audio mixing. We know, for example, that when video must be displayed that does not exist yet (e.g., a dissolve or a wipe), it must be rendered. The render is a mixdown of all the video elements into one composite video clip that can be played out to Firewire.

Video has a much higher data rate than audio, and the processing to show a real time playback of such unrendered material requires extra hardware and processing power from a real-time video card, such as the MatroxRTMac or the Promax RTMAX. Audio, on the other hand, can be mixed and output to Firewire without rendering, up to a certain point. The rule of thumb is that eight tracks of audio that have no effects applied to them can be mixed together down to two channels and sent out to Firewire along with video. This is referred to as real-time audio mixing.

So what do you do if you need more than eight tracks? You can simply perform a quick Mixdown Audio from the Sequence drop-down menu for the sequence. The ensuing render is quite fast; it’s much faster than video rendering. At the end of the render process, the audio tracks in the sequence will still be discrete and editable, but the audio tracks in the sequence will be linked to a render file so that everything above eight tracks can be mixed together and played correctly. If you have too many audio tracks to play back without Mixdown Audio, you will hear a pulsing beep alarm as you play back.

Sometimes, your system may not have the wherewithal to mix all the eight tracks of audio that it is generally capable of doing. This can yield Dropped Frame errors and can be the result of disk fragmentation, sluggish system performance, or any of various other reasons. In these instances, a quick Mixdown Audio will usually take the stress off of your processor or drives and allow your system to do what you want. Remember that the number of tracks you assigned in the Real Time Audio Mixing field of the General tab in the Preferences is the number of tracks you are limiting Final Cut Pro to attempting to mix real time in the sequence. Setting this number higher than eight will not make your system perform better; it will just try to real time mix more tracks than most Macs are generally able to. Keep this preference set to 8 tracks or less.

The track portion of the sequence is divided into two parts: the Target Track Selection Area to the left and the actual Timeline area to the right. The target track selection area is of crucial importance for editing, because of the flexibility it allows you when editing into the sequence. There’s more than one way to skin a cat, but some ways provide quicker skinning than others. Properly controlling the target track selection area can save you lots of time.

The target track selection area

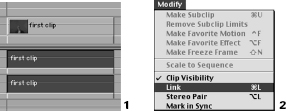

To the far left of the target track selection area, there is a green light for each track (Figure 5-38). This is called the Track Visibility switch. Clicking off this green light grays out the track and makes it unavailable to the sequence. It’s basically a way to hide a track’s contents temporarily. Any audio in the track would not be heard, and any video in the track would not be seen. Some care must be taken with this; turning tracks off irrevocably breaks the link between a clip and its render files. If you have rendered a clip, you want to avoid turning its track off.

The middle item in the target track selection area is the Target Track assignment. For video tracks, this is displayed as a small film frame next to the track’s name. For audio tracks, this is displayed as two little speakers pointed in opposite directions. In either case, the track of which the icon is displayed in yellow is a current target track. A target track is the track into which clips will be accepted when they are brought into a sequence. When you perform an Insert or Overwrite edit from the Canvas, the clip is automatically routed into whichever tracks are set as the target tracks.

In our examples of Insert and Overwrite earlier, there were only an initial video and two audio tracks in the sequence. This was sufficient for the requirements of our standard, DV-captured clips that are composed of one video and two audio tracks. But in some instances, you will need to create more tracks than this. To make sure that your edits get sent to the proper tracks, you must make sure that they are targeted.

Clicking on a track icon turns it yellow and sets it as the target track. For audio tracks, there can be two target tracks, since the Firewire connection with our DV device supports two channels out. The target track allows for a designation of a left and right, or stereo pair, in the target track box, since most clips will have two channels of audio and many will also have hard panning, or extreme left-right differentiation between the two tracks. Only one track of video can be targeted at a time, since an individual clip will have only one associated layer of video (although through Nesting, which is covered further on, it’s easy to include many layers within that one layer).

Setting the target track is critical for editing when using more than one video and more than two audio tracks. Target track assignments do not change until you change them. If you are using the Drag to Canvas method of editing, the target tracks are the only way Final Cut Pro knows where to send the incoming clips. As you speed up your editing process by accessing keyboard shortcuts and automated features such as Drag to Canvas editing, you can easily screw up by not defining things like target tracks.

Finally, there is a Track Lock feature to the right of the target track selection area, symbolized by a padlock. Normally, this is in the unlocked position, given that you want to be able to work in the tracks, which locking them would disallow. But Track Locking can be very useful. No matter how experienced you are with Final Cut Pro, it can sometimes be tricky to see all the consequences of a single action. One false move could undo hours of precise cutting through an accidental series of edits. Locking tracks in these instances is a good way of making sure that nothing happens to a track or tracks when you are sure they are complete. It’s also a good way to lock two tracks that have been manually synced so that they cannot be accidentally shifted by subsequent edits.

Timeline customization controls

Below the tracks are various controls for adjusting the Timeline so that you can customize what you see and how much you see of the clips in your sequences. There are tools for changing the time scale of the Timeline so that you are looking at larger or smaller increments of time, a timecode field for indicating where the playhead is at the moment, and, finally, buttons that can provide additional control and display of the tracks themselves.

The Time Scale of the sequence Timeline is the variable increment your sequence contents are displayed with. Because your clips may range in length from several seconds to several minutes, it can sometimes be difficult to view all the contents of the sequence at once. Similarly, you may need to edit your clips on a very large scale so that you can distinguish between frames in a clip. You need to be able to adjust the time scale of the Timeline so that you can alternate between looking at all the contents of your sequence and focusing on a smaller section of it.

The time scale bar

At the bottom right-hand corner of the Timeline window, there are two controls that adjust the time scale of the Timeline: The Zoom Slider and the Zoom Control Meter. The Zoom Slider is a manual scrolling bar control with a handle on either end (Figure 5-39). The Zoom Scroll bar only works when there is a clip on the Timelime to change the scale of. If you grab either one of the handles and drag it, you will see that the increments above the tracks become larger or smaller. Drag the bar out longer, and you will be looking at seconds—even minutes, depending on the length of the clips in the sequence. Drag either of the handles in to make the bar shorter, and you will be looking at smaller increments, down to single frames of video. This can be especially helpful when you need to make very specific adjustments to positioning of clips or if you need to select many different clips at once. Adjusting the time scale allows you to put as little or as much of your sequence contents into the viewing area as you need.

This bar can actually move the viewing area of the Timeline as well. Grabbing the bar anywhere between the handles and dragging moves the whole viewing area forward and back along a sequence’s length, allowing you to move to areas quickly without having to get there by moving the playhead. Remember that this movement does not move the position of the playhead itself and that you will need to move it up to the window by clicking within the view area.

![]()

![]()

Navigating on the Timeline efficiently is a skill in itself. There is no correct timescale. The appropriate timescale depends as much on the relative lengths of your clips as it does on the type of editing you need to do at the moment. Your ability to quickly change the scale and move to the next area of the sequence takes time and practice, but to work efficiently you really need to master it.

The Zoom Control meter

Because Timeline navigation is so important, Final Cut Pro provides a couple of other tools for quick and precise Timeline redefinition (Figure 5-40). The next tool to the left of the navigation bar is the Zoom Control. It is shaped like a meter and redefines the time scale based on where the marker is in the Zoom Control box. When the marker is further to the right, the time increments will be larger, meaning that you will be looking at whole minutes and can see more of the sequence at a time. Moving the marker to the left makes the increments smaller and more precise. Move the marker to the extreme left and you will see each individual frame; move it to the extreme right and you will be looking at a much larger scale that allows you to see every clip that sits in the sequence. In between these two positions are jumps in scale that you can access based on your needs.

Playhead Timecode Field

To the left of this meter is the sequence Playhead Timecode Field (Figure 5-41). This field has two major functions. The first is to display the frame that the playhead is currently parked on. Since this is a timecode value for the sequence and not for the clips within it, the first frame of the sequence will be the Starting Timecode value you entered in the Timeline Options tab in the Preferences. If you did not change the default value there when you set the Preferences, the Starting Timecode value will be 01:00:00:00. You can of course change this value to any number that you want, given your system of organizing timecode values for your project.

![]()

The second function of the field is to manually position the playhead at a specific timecode location (Figure 5-42). Navigating to a specific frame to make an edit can be crucial. Entering values into this box is simple; you don’t even have to click on the box to do so. Because this box is the only place you can enter numeric information into the Timeline window, simply typing numbers when the Timeline window is active will enter them there.

Final Cut Pro makes things even easier. Although timecode values require colons or semicolons to delineate hours, minutes, seconds, and frames, Final Cut Pro can insert these for you. All you need to do is type in the numbers and make sure that you enter zeros where applicable—for example, type 01000300, and Final Cut Pro will convert this to 01:00:03:00, or the third second of the Timeline. When you hit the enter key, Final Cut Pro will insert the colons and move the playhead to the new location. It can even intuit that the earlier values stay the same if you enter only a few. For example, typing in the above value lands the playhead on 01:00:03:00. Then typing in 15 will move it up to 01:00:03:15. Typing in 215 will then move it to 01:00:02:15.

To make things even more convenient, you can type in a certain number of frames to retreat or advance. Instead of having to do the math to figure which frame to move to, simply type in + or – followed by a number, and the playhead advances or retreats that many frames, seconds, minutes, or even hours. For example, if you are at 01:00:02:00 and you want to move up to 01:00:03:00, simply type in +100, or plus one second and zero frames.

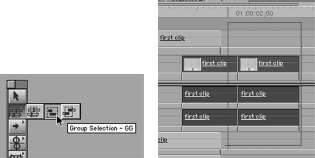

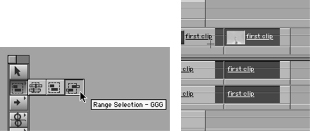

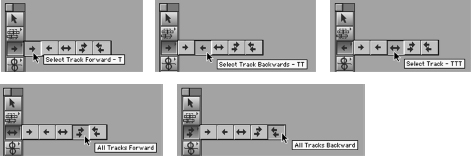

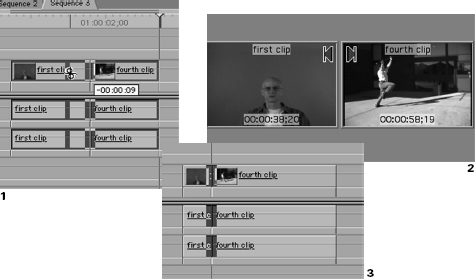

Using the numeric keypad for navigation is the easiest way to work. Rather than wear your wrist out using the mouse to drag a playhead around, move it exactly the distance you want. But what if you want to advance or retreat only one frame? The keyboard shortcut for advance/retreat one frame is the Left and Right Arrow key. Holding the Shift key and hitting the Left and Right Arrow key changes this to advance/retreat one second.