An Introduction to Forensic Accounting

Executive Summary

Business and accounting scandals (Madoff, Satyam, Stanford Financial, and subprime mortgage fraud) have dominated the business news in the past several decades. Numerous cases of high-profile alleged FSF (e.g., Enron, WorldCom, Parmalat, Satyam) as well as the investment Ponzi schemes and credit crunch scandals have negatively affected the financial markets and investors’ confidence in public financial information. Forensic accounting has advanced as an important and rewarding field of accounting to prevent, detect, and correct these financial scandals and other types of fraud. In such an increasingly unstable economic and litigious environment, there has been significant growth in the demand for and interest in forensic accounting and investigative services. Forensic accountants provide litigation consulting, expert witnessing, valuation, and fraud investigation services. This chapter presents an introduction to forensic and investigative accounting.

Introduction

Forensic accounting is a growing and ever-changing field of accounting with tremendous opportunities for advancements. Forensic accounting services of fraud investigations, litigation consulting, valuation, and expert witnessing are both rewarding and exiting. For example, tracking down criminals by holding them accountable for committed illegal acts can be a tedious task but rewarding in making our society safer and free from material wrongdoings and frauds. The field of forensic accounting has grown significantly over the past decades and is expected to make further progress as the demand for, and interest in, forensic accounting services increases.

There is also a growing need for business schools and accounting programs to train and educate the most competent and ethical future forensic and investigative accountants. This field is not specific to any country, industry, or organization; as such, there are numerous employment opportunities available. Forensic and investigative accounting is viewed by many as one of the most exciting, rewarding, and secured career tracks.1 However, there appears to be a gap between forensic and investigative accounting practice and education, given that there is only a limited number of forensic accounting modules/courses offered within accounting and business curricula in universities worldwide.2 A few existing textbooks in this area all primarily focus on occupation fraud with a limited coverage of Financial Statement Fraud (FSF). This chapter develops an awareness and understanding of the main themes, perspectives, frameworks, and issues pertaining to forensic and investigative accounting. This chapter presents an introduction to forensic accounting with a keen focus on the knowledge and the professional and personal skills needed to become successful forensic and investigative accountants, such as adequate knowledge in accounting, law, criminology, psychology, auditing, and business and (FSF) examination.

Definition of Forensic Accounting

Forensic accounting is the application of technical accounting, investigative, and law as well as analytical and communication skills for the purpose of resolving financial and nonfinancial issues in a manner that meets the standards required by courts of law.3 Forensic and investigative accounting is generally defined as the practice of rigorous data collection and analysis in the areas of litigation support consulting, expert witnessing, valuation, and fraud examination.4 Thus, forensic accountants conduct investigative, financial analysis, and valuation services, the result of which could be used in a court of law. Forensic accountants apply special skills in accounting, auditing, finance, business, psychology, quantitative methods, analytical analyses, law, criminology, research, and investigative skills to collect, analyze, and evaluate evidential matters and to interpret and communicate findings.5 Forensic accounting is a field in which accountants use their accounting knowledge along with complex investigation skills to assist in fraud investigation, expert witnessing, valuation and litigation, and investigative services. Forensic accounting is a process of gathering and evaluating evidence and reaching conclusions when conducting a fraud investigation, performing litigation services, determining asset and liability valuation, or testing as an expert witness.

Forensic and investigative accounting practices include fraud examination, investigation of corruption and bribery, business valuation, being an expert witness, cybercrime management/cybersecurity, and litigation support.6 Furthermore, forensic and investigative accounting services range from expert report preparation to appearing in the witness box and from carrying out a fraud investigation to interviewing witnesses and securing evidence. As a rapidly growing area within the accounting profession, forensic accounting has gradually been recognized by professionals, including the formation of a new professional certification—Certified Fraud Examiner, American Accounting Association forensic accounting section, development of new continuing professional development courses on the subject of fraud, Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) focus on fraud, and forensic accounting divisions of public accounting firms. The academic community and research scholars have, in recent years, shown much interest in forensic accounting by publishing new forensic accounting textbooks and developing modules/courses about forensic accounting and conducting research on various aspects of forensic accounting published in the accounting and business journals. Exhibit 1.1 shows a list of selected books in forensic and fraud-related subjects. Within forensic accounting, fraud in general is defined as an intentional wrongful act to injure, damage, or deceive others, and thus, FSF is viewed as intentional manipulation or misstatement of material financial information to mislead users of financial statements.7 The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) classifies occupational fraud in three primary categories: asset misappropriation, corruption, and (FSF).8 This book is different and complements existing books listed in Exhibit 1.1 by focusing on both FSF and nonfraud (valuation, expert witnessing, litigation consulting) forensic accounting services.

Status of Forensic Accounting

Forensic accounting has been practiced for many decades and has become more relevant in the aftermath of the wave of financial scandals at the turn of the twenty-first century and the 2007 to 2009 global financial crisis. In 2013, CNNMoney reported that 1,216,900 individuals were employed as forensic accountants with an expected 10-year growth of approximately 16 percent.9 The median salary was $103,000 in 2013, which, when compared with over median auditor and tax accountant salary in 2016, is 51 percent higher.10 Employment in forensic accounting has significantly grown in the past decade with a steady annual rate of 18% from 2012 to 2017 according to a report published by market research firm IBISWorld.11 This increasing growth in forensic accounting services is expected to continue in foreseeable years as the accounting profession establishing more robust guidelines for forensic accounting engagements of a forensic standard is intended to improve consistency and quality. The growth rate for other accountants and auditors is only 10 percent, in comparison; thus, the steady growth in the forensic accounting profession is expected to continue.12

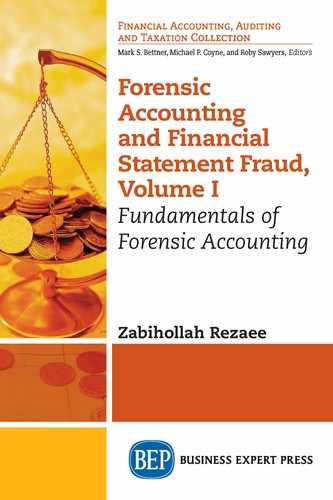

One important area of forensic accounting practices is fraud examination. FSF has been detrimental to the integrity and quality of public financial information, and Congress passed the Sarbanes–Oxley Act (SOX) of 2002, which was intended to combat FSF. However, in the several years post-SOX, the Department of Justice has obtained nearly 1,300 fraud convictions between 2002 and 2009.13 The 2010 Committee of Sponsoring Organizations (COSO) report indicates the following: (1) FSF persisted in the past two decades with 347 incidents between 1998 and 2007 compared with 294 cases from 1987 to 1997; (2) the magnitude (mean per cases) of FSF during 1998 to 2007 was about $400 million compared with a mean of $25 million per case between 1998 and 1997; (3) FSF cases were committed with some level of involvement of senior executives (CEO, CFO) in 89 percent of studied cases in 1998 to 2007 and about 83 percent of cases in 1987 to 1997; (4) almost 20 percent of alleged fraudulent executives were indicted from which more than 60 percent were convicted; (5) the most common FSF schemes continue to be improper revenue recognition followed by overstatement of assets; (6) over one-fourth of fraud firms changed auditors either during the fraud period or in the fiscal year preceding the fraud period; and (7) fraud firms experienced negative consequences of fraud either in terms of decline in stock prices, bankruptcy, or delisting from major stock exchanges.14 Exhibit 1.2 presents many career opportunities in forensic accounting.

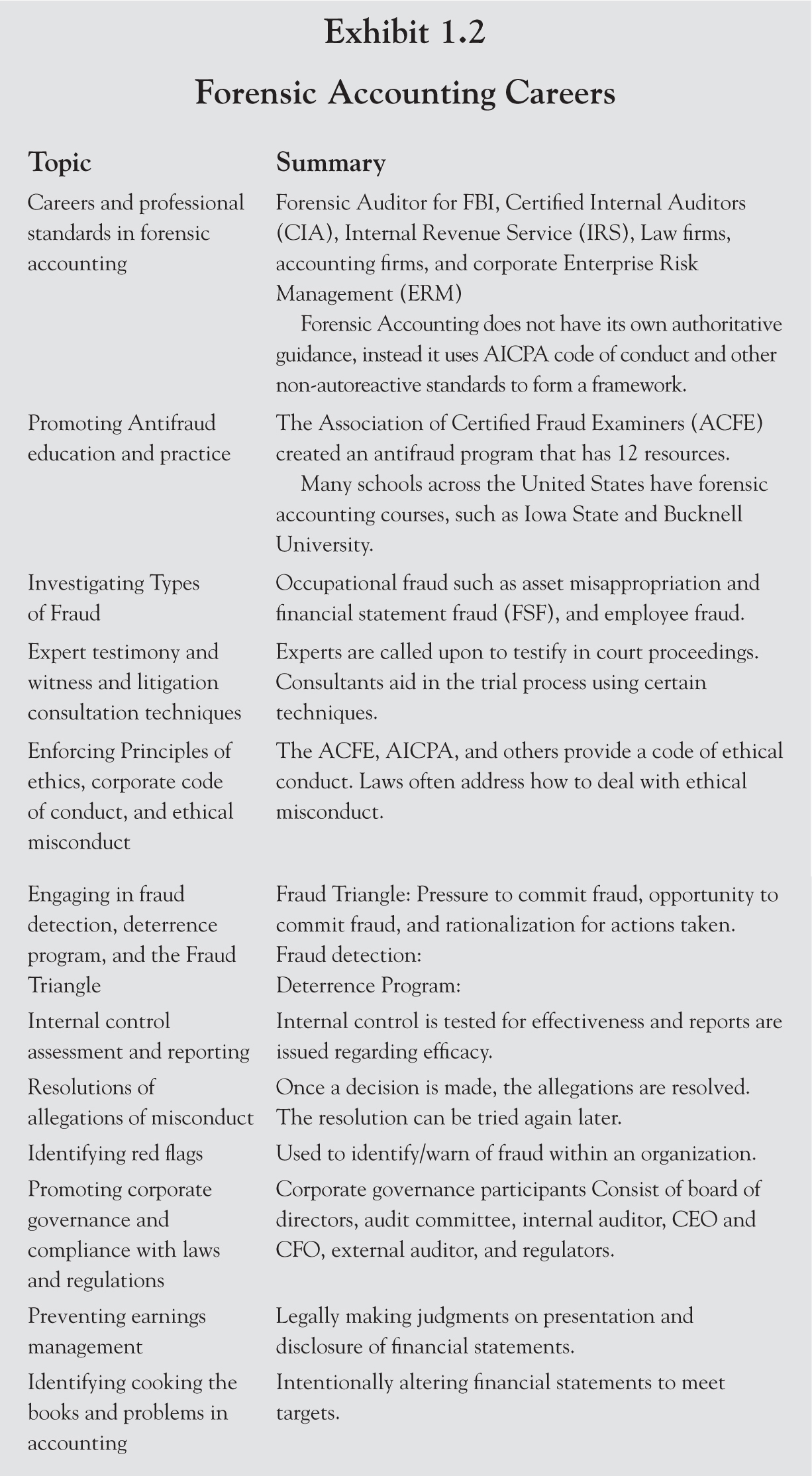

Forensic accounting is a growing field of accounting. All “Big 4” accounting firms of Deloitte, Ernst and Young, KPMG, and PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) and many of other national and international accounting firms have forensic accounting departments and specialists now and are hiring forensic experts in increasing numbers. Common services include all manner of cyber risk management (security, risk, and analytics), eDiscovery, computer and cybercrime forensics, managing fraud risk, and all manner of dispute resolution. Exhibit 1.3 presents specifications of the forensic accounting departments of top 10 public accounting firms, including the Big 4, as well as their forensic accounting services provided, their roles, responsibilities, commitments, and websites. The steady growth and expansion of forensic accounting services is driven by the downturn in the economy and financial challenges and as corporations struggle, crime and FSF increase.

As the forensic accounting field is growing, there is a noticeable disconnect between the number of jobs available and the number of professionals available. With a high demand for forensic accountants, firms have been able to raise their fees and have higher hiring standards. This is evidenced by many professionals expecting growth in forensic accounting from 2015 to 2020.15 Each Big four firm, as well as other accounting firms, has its own website. On the website, there is a page related to forensic accounting services that the firm offers. For example, PwC offers digital forensics, fraud risk mitigation, a crime unit, investigation solutions, and many others. The services offered by PwC, KPMG, Deloitte, and Ernst & Young (EY) are similar but deviate highly from the smaller firms, such as Moss Adams and Baker, Tilly, Virchow, and Krause. The existence of this gap can be explained by firm size, technological capability, human capital, and revenue available to spend on forensic services.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)’s forensic accountants investigate terrorists, spies, and criminals who are involved in financial crime. For the FBI, these accountants participate in court proceedings using knowledge of legal procedure and policies, principles for evidence gathering and presentation, and security protocols dictated by law. Prior to engaging forensic accountants to practice, the FBI administers a live course to understand the systems, skills, techniques, and expertise that the field offices require.16 The responsibilities of FBI forensic accountants include performing thorough forensic financial analyses of the records of those suspected of illegal activity, gathering evidence, preparing search warrants/affidavits, going with case agents on subject/key witness interviews, piecing together funding sources and interrelated transactions, generating investigative reports, meeting with prosecutors to strategize, offering support during proceedings, and acting as expert witnesses. After the training session, the FBI assigns accountants to various teams, including forensic accounting squads and the Forensic Accountant Support Team.17

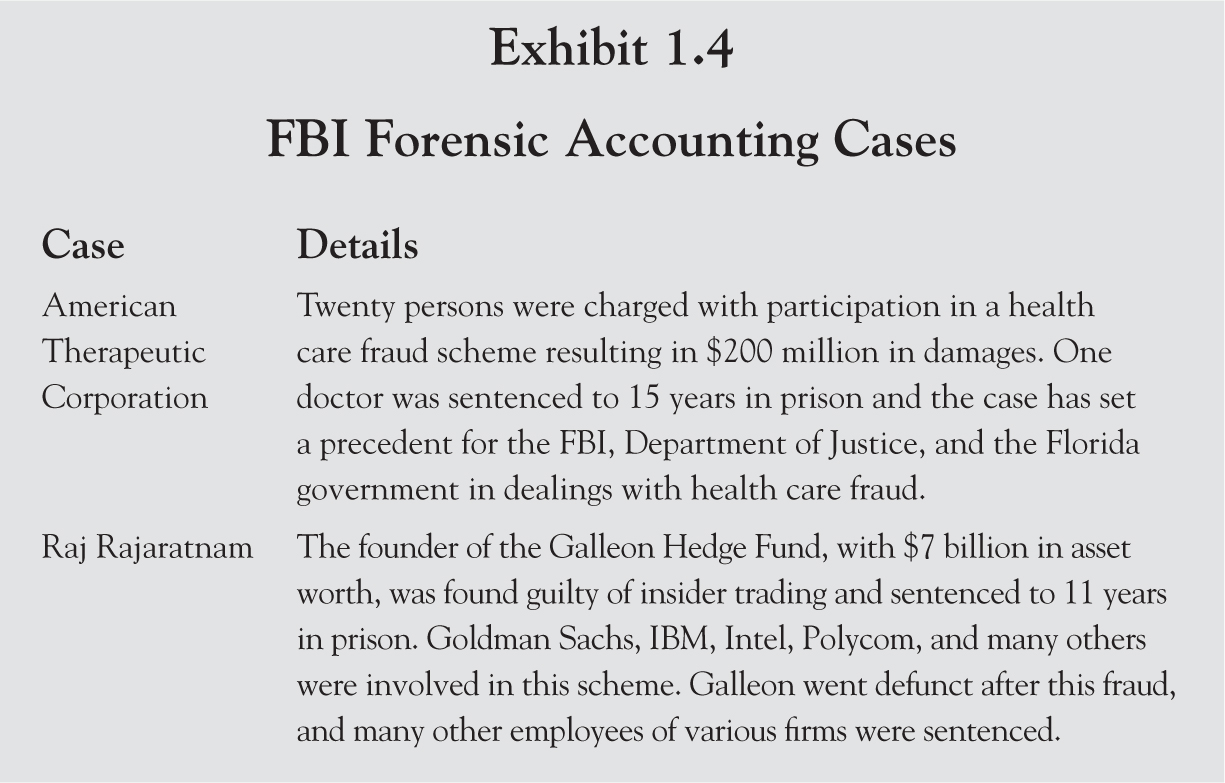

Forensic accountants can be employed by public accounting firms, the FBI, insurance firms, governmental agencies, law firms, and/or finance companies.18 A prominent case in recent history is a $200 million Medicare fraud in which two employees of American Therapeutic Corporation recruited beneficiaries. Another case involved insider trading of hedge funds by Raj Rajaratnam. More information on these cases is included in Exhibit 1.4. On the cases, several techniques were used to help find the perpetrators guilty. First, interviewing was used heavily in these cases. Interviewing is often used to gather specific information to be used during trial. Second, the verification of red flags is used. In the above-mentioned cases, kickbacks and prior legal troubles are probable causes of wrongdoing as illustrated in Exhibit 1.4. In the aftermath of financial scandals and the 2007 to 2009 global financial crisis, the focus on FSF prevention and detection has become more important as regulators, investors, and companies seek better understanding of corporate malfeasance and misconduct. However, nonfraud forensic accounting services such as litigation consulting, valuation, and expert witnessing are gaining considerable attention in recent years.

Crime occurs across countries and continents, so forensic accountants have opportunities for careers worldwide. Even though technology has brought the world closer together, technology has not changed cultural differences or human beings’ responses to pressure, incentives, and opportunities to engage in fraudulent and wrongful actions. The role of information technology has greatly increased in the detection of fraud and the committing of fraud. Forensic accountants need to possess a different skill set from that of traditional accountants. They need to be analytical, detail-oriented, skeptical, and ethical. Forensic accountants provide a wide range of services, including financial data analysis, evidence integrity analysis, computer application design, writing reports, compiling information, testifying as an expert witness, eliciting other experts’ assistance, maintaining documentation, making damage assessment, tracing illicit funds, locating hidden assets, exercising due diligence reviews, gathering forensic intelligence, and conducting business valuation.

The ACFE’s 2016 report to the nations indicates that the median loss caused by the occupational fraud cases was $160,000; the most common form of fraud was FSF, causing a median loss of $975,000; corruption schemes were in the middle, comprising just under one-third of cases and causing a median loss of $200,000; and asset misappropriation schemes were the least costly, causing a median loss of less than $125,000.19 More than 80 percent of fraud cases were committed by individuals in one of six departments: accounting, operations, sales, executive/upper management, customer service, or purchasing, and about 85 percent of fraudsters had never been previously charged or convicted for a fraud-related offense.20 The ACFE has updated its report to the nations on occupation, fraud, and abuse annually in the past several years. The ACFE’s 2018 report focuses on five critical areas of occupational fraud. These five areas include the methods and means by which occupational frauds are committed and detected, the characteristics of the organizations that are victimized, and people who commit occupational fraud and results of the cases.21 The 2018 study shows the analysis of 2,690 cases of occupational fraud, and results are similar to those of 2016 study, with 89 percent of occupational fraud committed being related to asset misappropriation with the median loss of $114,000, 38 percent of cases pertaining to corruption with the median loss of $250,000, and 10 percent of cases being related to FSF with the median of $800,000 loss per year.22

The long-term sustainability of the specialized field of forensic accounting and fraud examination will depend on the ability to test (using scientific methodologies) those tools and techniques currently used in the field, as well as the ability to research new innovative ideas to address fraud and forensic accounting issues, but also issues associated with law, sociology, psychology, criminal justice, intelligence, computer forensics, and application tools and techniques pulled from other forensic sciences. The need for trained fraud and forensic experts continues to growth.

Contrasting Forensic Accounting with Conversional Accounting and Auditing

Forensic and investigative accounting is a subfield of accounting with its own set of purposes, specializations, skills, and requirements. However, there are many similarities and differences between conventional accounting/auditing and forensic accounting. Similarities are the common goal of identifying, measuring, classifying, analyzing financial information, preparing reports, and communicating results to interested users of these reports. The main differences between a conventional accounting and forensic accounting are the intended purposes and users. Conventional accounting is a process of identifying economic events and business transactions, measuring, classifying, and recognizing their financial impacts, preparing a set of financial statements reflecting results of operations and financial positions, and conveying such useful, reliable, and relevant financial information to interested users of financial statements including investors and other users of financial statements. Users of financial reports use financial information in making decisions.

There are also some similarities and differences between traditional auditing and forensic accounting. Auditors typically gather evidence relevant to reported financial statements, evaluate its sufficiency and competency, reach audit conclusions, and communicate their audit opinions to users of financial statements. The audit opinions are intended to lend more credibility to the reported financial statements. Auditors provide reasonable assurance that the audited financial statements are free from material misstatements whether caused by error or fraud. Auditors are professional independent contractors who opine on financial statements by maintaining their objectivity, independence, and impartiality from their clients and do not compromise their professionalism in benefiting one user at the expense of other users of financial statements.

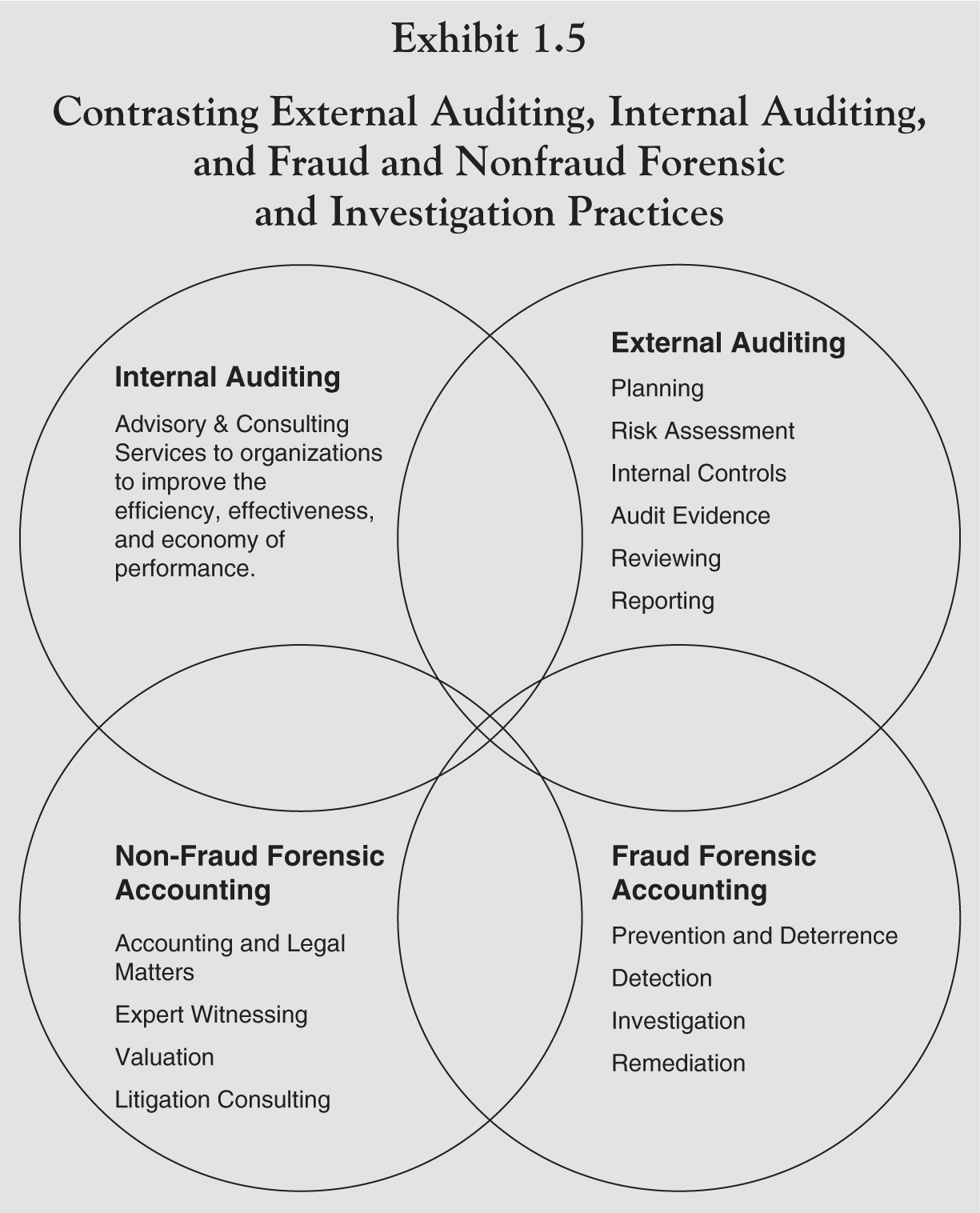

Forensic accountants often use the same methods as traditional auditors in gathering and evaluating both financial and nonfinancial information in reaching conclusions about its relevance and reliability and use such information in expressing professional opinions on issues pertaining to judicial guidelines on evidence and the applicable law. In this respect, forensic accounting is similar to conventional auditing. Forensic accountants use similar audit procedures in gathering and evaluating evidence and use professional skepticism in expressing opinions. There are some overlaps between the work of fraud forensic accounting, nonfraud forensic accounting, and internal and external auditing as depicted in Exhibit 1.4. However, the objectives of audit engagements are different from those of forensic accounting.

The objectives of a traditional audit are to provide reasonable assurance that audited financial statements are free from material misstatements whether caused by error or fraud. The objectives of a forensic accounting engagement are also to express an opinion on a set of financial and nonfinancial information and communicate findings and make recommendations and testify to the findings.23 Exhibit 1.5 compares traditional internal and external auditing with fraud and nonfraud forensic accounting. In fraud forensic accounting, investigators investigate allegation of fraud, gather evidence to substantiate the fraud allegation, and report on the findings. In nonfraud forensic accounting, accountants serve as litigation consultants, expert witnesses, or valuation experts in gathering evidence and opining on the disputed matters.

Professional guidelines and standards used by auditors and forensic accountants are different. Audits of public companies in the United States, post-SOX, should be performed in compliance with the auditing standards of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB).24 Forensic accountants comply with all applicable laws, rules, regulations, and standards, rules of evidence, criminal and civil procedures, and other professional guidelines and pronouncements in conducting their forensic accounting services. Forensic accounting and traditional financial auditing have a different foundation. For example, the certified public accountants (CPAs) who perform forensic accounting services should observe Consulting Services section 100 of “consulting Services: definitions and Standards of the American Institute of CPA (AICPA) Professional Standards.”25

Forensic accounting standards arise from courts and the precedents (law) set by them. Financial accounting standards are developed by the SEC and its designated professional organization, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) in establishing guidelines for the preparation of financial statements of public companies. The accounting standards provide guidelines for identification, classification, measurement, and recognition of business transactions and for the preparation of related financial statements (balance sheet, income statement, the statement of cash flow, and the statement of owners’ equity). Auditing standards for auditors of public companies are set forth by the PCAOB in the post-SOX era to provide guidelines for auditors in lending more credibility to published financial statements. Forensic accounting standards are tailored to identification and prevention procedures. External auditors primarily focus on discovery of material misstatements whether caused by error or fraud, whereas forensic accountants focus on fraud prevention and detection. When auditors detect allegations of fraud through the normal practice of audit of financial statements, it becomes cumbersome for them to prove that fraud occurred. External auditors typically employ and retain forensic accountants to detect the alleged FSF. On the contrary, forensic accountants consider fraud detection as their main goal, and when they discover fraud, they have fulfilled their responsibility.

Audit procedures and processes are essential to any investigative effort, and they differ between forensic accountants and traditional auditors. Both forensic accounting and auditing involve standard auditing procedures, such as evidence gathering, future analytical tests, and sampling. Forensic accountants also utilize several, unique areas to benefit the workload. These areas are criminalistics, forensic evidence, testimony from experts, and using computer technology to conduct forensic investigations. Criminalistics is a process in which gathering and analysis of evidence occurs. The evidence can range from fingerprints taken to computer and handwritten documentation. Forensic accountants mostly use evidence relating to computer and written documentation. This type of evidence is defined as being physical and tangible in nature. The two above-mentioned specialties of forensic accountants are applied through practice and instruction; however, to apply these correctly, the accountant must be knowledgeable in expert testimony. This requires the accountant to have sufficient and competent evidence to present in court. The forensic accountant works alongside lawyers to aid in the resolution of cases. In recent years, computer technology has provided forensic accountants, the ability to assimilate data and decipher it at an ever-increasing rate. This process is referred to as digital forensics when using forensic investigation on digital devices such as computers.

Conclusion

Forensic accounting is a growing and changing field that is both challenging and rewarding. Forensic accountants are commonly hired to uncover fraud, discover fraudsters, minimalize the effects of fraud, and try to prevent fraud in the future. They can also be utilized in other cases such as divorce, terrorist activities, business valuations and criminal investigations. Forensic accountants must be able to detect fraud, trace illicit funds, implement activities to prevent future fraud, and provide an adequate burden of proof. Forensic accountants need to possess different skill sets, from traditional accountants to investigators and digital forensic practitioners. They need to be technical, analytical, detail-oriented, good communicators and ethical. This specific set of skills for forensic accountants helps plead the case for higher education institutions to provide courses that will train future forensic professionals. The need for formal and consistent educational programs focusing on the indicators of fraud and nonfraud schemes is beneficial to all business students. Moving forward, this will hopefully become a priority in higher education to prepare all students, not just accounting students, to become competent and ethical future leaders in the business world.

Action Items

- Forensic accounting is a field of accounting with specific expertise, knowledge, and skill sets.

- Forensic accounting skill sets are in areas of technical skills (accounting, auditing, finance, law, psychology, and criminology), analytical skills (data gathering and analyses), and soft skills (communication and interviewing).

- Forensic accounting is gaining considerable attention in the aftermath of the financial scandals at the turn of the twenty-first century and the 2007 to 2009 global financial crisis.

- Forensic accounting is a challenging, demanding, and rewarding field of accounting.

Endnotes

1. Z. Rezaee, J. Wang, and B. Lam. January–June, 2018. “Toward the Integration of Big Data into Forensic Accounting Education,” Journal of Forensic & Investigative Accounting 10, no. 1.

2. Ibid.

3. Z. Rezaee, L. Crumbley, and R. Elmore. 2004. “Forensic Accounting Education: A Survey of Academics and Practitioners,” Advances in Accounting Education Teaching and Curriculum Innovations 6, pp. 193–232.

4. Ibid.

5. W.S. Hopwood, J.J. Leiner, and G.R. Young. 2008. Forensic Accounting (1st ed., Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Irwin).

6. L. Crumbley, L. Heitger, and S. Smith. 2015. Forensic and Investigative Accounting (7th ed., Chicago, IL: Commerce Clearing House).

7. Z. Rezaee, and R. Riley. 2009. Financial Statement Fraud: Prevention and Detection (2nd ed., Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons).

8. D. James, and C. Ratley 2016. Report to the Nations on Occupational Fraud and Abuse (Austin, TX: Association of Certified Fraud Examiners).

9. CNNMoney. 2013. Best Jobs in America. http://money.cnn.com/pf/best-jobs/2013/snapshots/24.html

10. Ibid.

11. IBISWorld. 2019. IBISWorld Industry Report 54121c: Accounting Services in the US, February 2019. Available at https://clients1.ibisworld.com/search/default.aspx?st=Forensic%20Accounting%20Jobs

12. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2016. Accountants and Auditors. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/business-and-financial/accountants-and-auditors.htm#tab-1

13. Rezaee and Riley. 2009.

14. Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO). 2010. Fraudulent Financial Reporting: 1998-2007: An Analysis of U.S. Public Companies. https://www.coso.org

15. F. Vinluan. March 1, 2015. “Finding Growth in FVS,” Journal of Accountancy. https://www.journalofaccountancy.com/issues/2015/mar/cpa-forensic-and-valuation-services.html

16. FBI. March 9, 2012. FBI Forensic Accountants. https://www.fbi.gov/news/stories/fbi-forensic-accountants

17. Ibid.

18. ACFE. n.d. Career Path—Forensic Accountant. http://www.acfe.com/career-path-forensic-accountant.aspx, (accessed November 21, 2017).

19. Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE). 2016. ACFE Report to the Nations, Downloads. https://www.acfe.com/rttn2016/resources/downloads.aspx, (accessed October 7, 2017).

20. Ibid.

21. Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE). 2018. Report to the Nations: 2018 Global Study on Occupational Fraud and Abuse. https://www.acfe.com/uploadedFiles/ACFE_Website/Content/rttn/2018/RTTN-Government-Edition.pdf

22. Ibid.

23. D. Gray. 2008. “Forensic Accounting and Auditing: Compared and Contrasted to Traditional Accounting and Auditing,” American Journal of Business Education 2, no. 2.

24. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB). 2018. Auditing Standards. https://pcaobus.org/Standards/Pages/default.aspx

25. The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). 2018. Professional Standards: Forensic and Valuation Services Professional Standards. https://www.aicpa.org/interestareas/forensicandvaluation/resources/standards.html