CHAPTER 1

Roles and Processes of Forensic Accounting

Executive Summary

Forensic accountants are often hired to investigate allegations of wrongdoing such as financial statement fraud (FSF), employee fraud, misappropriation of assets, misrepresentation of financial information, kickbacks, bribery, conspiracy, inside trading, valuation disputes, and money laundering, among other forensic accounting services. It is important for forensic accountants to understand the role of evidence, methods of gathering sufficient and competent evidence, evaluate evidence, reach conclusions, communicate findings, make recommendations, and testify before courts. This chapter discusses the roles of forensic accountants and processes of forensic accounting, including the types of evidence (i.e., direct and circumstantial), evidence-gathering procedures, evidence assessment, conclusions, opinions, recommendations, and testimony.

Introduction

Forensic accountants gather evidence by conducting evidence-gathering procedures, evaluate evidence in terms of sufficiency and competency, use evidence in forming opinions, communicate their opinions, make recommendations, and testify in courts about their opinions. This chapter presents fundamentals of forensic accounting in performing fraud and nonfraud services by examining the types of evidence (e.g., direct, circumstantial, testimonial, physical, and documentary), rules of evidence, methods of gathering and evaluating evidence, and reaching evidence-based conclusions. The expertise of forensic accountants is in higher demand than expected in the areas of expert witnessing, litigation consulting, and fraud investigation, because the advancement of technology has augmented the specialized skills of forensic accountants. The increasing prevalence of fraud justifies the growing demand for and interest in forensic accounting.

The Role of Forensic Accountants

Forensic accountants, also known as investigative auditors or forensic auditors, are professionals that are usually employed to investigate financial and nonfinancial matters owing to a dispute, fraudulent, or imminent legal proceedings. Effective performance of forensic accounting services require gathering of a huge amount of both structured (e.g., general ledger or transaction data) and unstructured data (e.g., e-mail, voice, or free-text fields in a database), together with an increasing amount of nontraditional data sources such as third-party watch lists, news media, free-text payment descriptions, e-mail communications, and social media. Data analytics with the use of Big Data has been employed by forensic accountants to transform unstructured data into useful, structured, and relevant information for decision making in performing forensic accounting services. Forensic accounting services are often performed by individuals, with multidisciplinary knowledge and experience in accounting, technology, criminology, psychology, and laws, who are professionally skeptical in asking the right questions, utilizing data science and data management expertise to translate questions into meaningful analytics and use systems and information technology (IT) infrastructures.1

Individuals performing forensic accounting services are often working with professionals that are considered to have certifications such as the Certified Public Accountants (CPA), Certified Forensic Accounting Credential (CFAC), Certified Fraud Examiner (CFE), Forensic Certified Public Accountant (FCPA), Certified in Financial Forensics (CFF), and Certified Valuation Analyst (CVA), among others. These certifications enhance forensic accountants’ competency, skill sets, and reputation. The new AICPA proposed standards, released in December 2018, classify forensic accounting engagements as services provided by members for “investigation” or “litigation”.2 The investigation engagements are services performed to reach a conclusion regarding concerns of wrongdoing in which the CPA performs necessary procedures to collect, analyze, evaluate, or interpret evidence on the merits of the concerns. The litigation engagements are actual or potential litigation services performed in connection with the resolution of disputes between parties in which the engagement does not need to be formal and may include alternative dispute resolution forum.

Forensic accountants should obtain sufficient understanding of how to plan and prepare for a forensic engagement, including considerations of whether to accept an engagement, defining the terms of the engagement, working with attorneys, identifying and managing resources, planning the engagement, and conducting the investigation. Accepting an engagement is an important step in the process of performing forensic accounting services. Forensic accountants base their opinion on the evidence gathered during their investigation. For example, a fraud investigation is the process of examining allegations of fraud, gathering convincing evidence, and reaching a resolution on the basis of evidence, reporting, testifying, and detection and prevention. Evidence is used as the foundation of a fraud examination, which is the basis for reaching conclusions. The evidence needs to be thorough, sufficient, competent, and credible in nature for the investigation to be appropriate. The sufficiency of the evidence is a matter of quantity about how much evidence is enough. The competency of the evidence is a matter of quality regarding whether the evidence is persuasive and credible.

The two main types of sufficient and competent evidence are documents and witness statements. The evidence should be evaluated and used as a basis for forming an opinion and writing a report. The report details the investigative process and the findings from the evidence used. Information often included in fraud reports are activities of the perpetrator(s), findings, and suggestions for improvement. Forensic accounting reports should be submitted to the interested parties. After the report has been issued, forensic accountants may be required to testify in court regarding the report and its findings. When testifying, the forensic accountant must take an oath to be honest and clear in communication and opinion.3 The effective planning for fraud and nonfraud forensic accounting services requires that forensic accountants understand the scope, type, and motives of fraud explained in the following sections.

Fraud Models

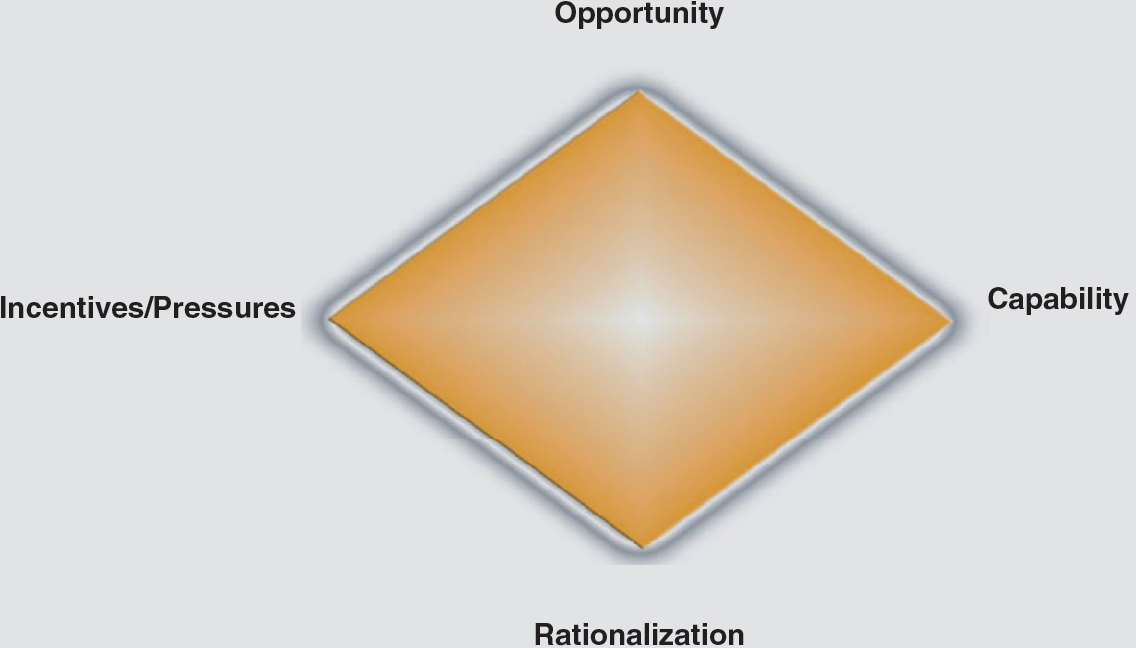

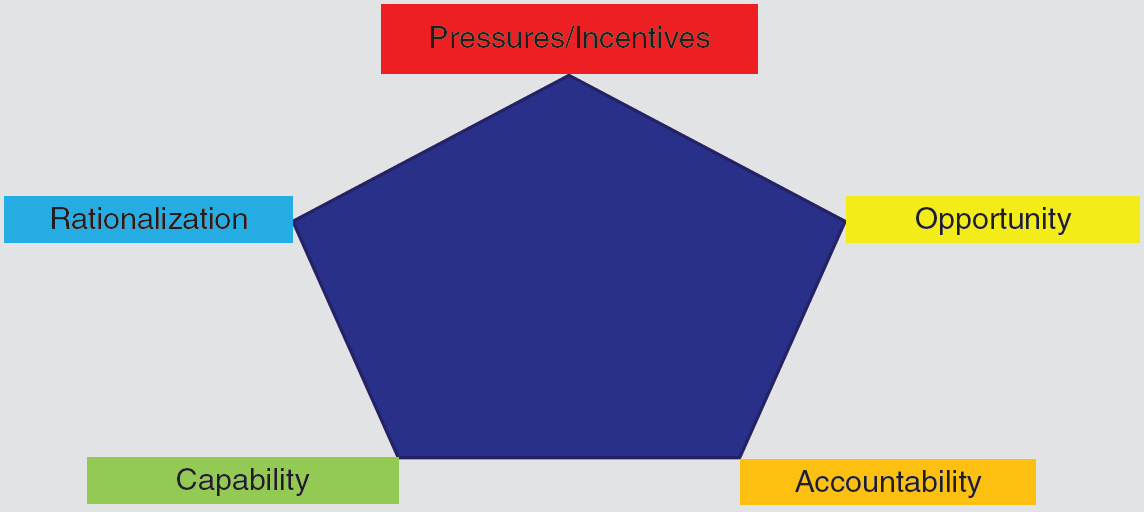

The nature, scope, and drivers of fraud can be defined in many ways, including the fraud triangle. The fraud triangle was initially conceptualized by Donald Cressey (1953) and consists of three components—incentive, opportunity, and rationalization.4 Fraud occurs when there are pressures or incentives to engage in fraud, opportunities to commit the fraud, and there is a rationalization for the actions taken; these can either be real or simply perceived by the fraudster. The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) issued the Statement of Auditing Standards No. 82 (SAS No. 82)5 and then SAS No. 99, “Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit” in 2002,6 which promotes the fraud triangle as a theoretical framework in the investigation of FSF. The fraud diamond was later developed by Wolfe and Hermanson (2004) who added “capability component” as the fourth dimension of the fraud diamond.7 The fraud diamond model includes incentives/pressures, opportunities, rationalization, and capability. The fraud pentagon model consists of five components—pressures/incentives, opportunity, capability, rationalization, and accountability. The inclusion of enforcement/compliance was introduced by Hossain, Mitera, and Rezaee (2016).8 Exhibit 1.1 (Panels A, B, and C) presents all three models—fraud triangle, diamond, and pentagon—and they are further explained in the following paragraphs.

Incentive is the motivation driven from conflicts of interest or a perceived pressure on individuals to commit FSF. In a corporate setting, incentive is typically examined in the context of operational/financial characteristics and as a motivating factor for management to adopt aggressive accounting policies and practices. Opportunity describes the conditions or corporate culture and environment that would allow management to commit FSF, which is often examined in the context of corporate governance effectiveness, adequate regulatory reforms, and vigorous enforcement of laws, rules, and regulations. Rationalization is a process by which management justifies its action in committing FSF and it can be addressed through psychological effects or mistakes in judgments in assessing the consequences of compromising ethical values or committing wrongdoings. Whereas incentive has been examined through the existence of internal and external pressures on management to achieve earnings targets or beat analyst earnings forecast and opportunity has been investigated through board and audit committee effectiveness and audit quality, rationalization has been difficult to examine because it is not easily measured.

To commit fraud, the fraudster must have adequate knowledge of the accounting systems and how they interact. Alongside the fraud models are four conditions that increase the likelihood of a person committing fraud; they are pressing financial need, opportunity, reasonable justification, and a lack of moral principle. The most serious of these aforementioned conditions is the lack of moral principle. This fraudster sees nothing wrong with committing fraud and will often continue to commit fraud as long as the opportunity is present. The conditions of people likely to commit fraud and all the fraud models have overlapping themes. The opportunity to commit fraud usually comes from a lack of or ineffective internal controls. Ineffective controls include the ability to override activities, no password constraints, and no preventions against collusion. If there is a strong separation of duties and multiple checks for areas with higher inherent risk, it is harder to commit fraud and easier to identify fraud. Rationalization, or justification, can stem from a real or perceived slight against the employee. It can also be rationalized by the employee by perceiving that the act is not actually stealing from the company. Also, the employee thinking that he or she is not hurting anyone or will be able to pay back the money before it is been noticed is also popular rationalization. This is important for forensic accountants to consider, so they can adequately examine the situations they are involved.

The pentagon model of financial reporting fraud (FRF) consists of five components: pressures/incentives, opportunity, capability, rationalization, and accountability through enforcement and compliance with all applicable laws, rules, and regulations. FRF occurs for a wide variety of reasons, more so when motives combine with opportunities. Corporate strategy to meet or beat analysts’ earnings forecasts pressures management to achieve earnings targets. Managers are motivated, in most cases, by pressure and reward when their bonuses are tied to reported earnings. This may induce managers to adopt accounting techniques that may often result in misreported earnings. Companies are more likely to engage in FRF when their actual earnings are predicted to fall short of certain thresholds. In such a situation, managers have incentives and pressures to manipulate earnings and engage in FRF by exercising their accounting discretion/flexibility available within the bounds of accounting standards. This is more likely when the benefits of manipulating earnings outweigh the associated costs and risks imposed by the adverse consequence of such frauds being detected.

The accountability element of the pentagon model of FRF is an extension of the fraud triangle model. All three factors—opportunity, incentive, and rationalization—must be in place for fraud to occur, and fraudsters must be able to commit fraud. Although the above-mentioned fraud elements deal with FRF prevention and detection, the accountability component is more relevant for FRF deterrence. The deterrence of FRF can be achieved when fraudsters realize that they will pay for the crime either through capital punishment or alternative severe criminal and civil penalties. The fifth component of FRF deterrence—“prevention and detection”—is accountability measured by effective compliance and vigorous enforcement of antifraud policies and procedures as well as severe punishment of fraud predators. Rezaee and Kedia (2012) present the following antifraud policies, procedures, and best practices of corporate gatekeepers, including the board of directors, management, internal auditors, and external auditors.9

The board of directors should establish the “tone at the top” by promoting competent and ethical behavior throughout the organization, effectively evaluating management performance and compensation as related to risk assessment, and vigilantly overseeing the financial reporting process and internal control system in preventing and detecting FRF. Management must design and implement an effective financial reporting process and internal control system while establishing a proactive approach to deter, prevent, and detect FRF. Internal auditors should provide both assurance and consulting services to their organization in the areas of operational efficiency, risk management, internal controls, financial reporting, antifraud, and governance processes. External auditors should provide reasonable assurance that financial reports are free from material fraud by integrating forensic procedures and fraud risk into audit strategies and tests and establishing open and frank dialogue with the board, audit committee, and management about the organization’s vulnerability to fraud.

FRF occurs for a wide variety of reasons, including when motives combine with opportunity. Corporations’ strategies to meet or exceed analysts’ earnings forecasts pressure management to achieve earnings targets. Managers are motivated and rewarded by achieving or exceeding target earnings, which can lead managers to choose accounting principles that may result in the misrepresentation of earnings. Companies are more likely to engage in FRF when quality and quantity of earnings are deteriorating, management has incentives and pressures to manipulate earnings, opportunities to engage in FRF exist, and management can have rationalized that the benefits outweigh the associated costs calculated using the probability and consequences of detection.

Economic incentives are common in FRF, even though other types of incentives such as psychotic, egocentric, or ideological motives may play a role. Pressure on management to meet analysts’ earnings forecast may give them the perception that their only option is to manipulate earnings. Management evaluates the opportunity for earnings manipulation and the benefit of earnings management in terms of the positive effect it will have on the company’s stock price against the possible cost of consequences of engaging in FRF and the probability of detection, prosecution, and sanction.

Antifraud roles and responsibilities of corporate gatekeepers are important because FRF is typically committed at the level of the top management team rather than lower management or employees. Senior executives are primarily responsible for fair presentation of financial statements, whereas the board of directors oversees the financial reporting process and auditors (external and internal) provide assurance regarding the reliability of financial reports. Both the 199910 and 201011 reports of Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO) find senior executives’ involvement in the high majority of FRF cases (i.e., 83 and 89 percent, respectively). When management has incentives to meet financial targets through earnings management and the opportunities to override internal controls exist, senior executives may engage in FRF as further explained in the next section.

Misstatements

Any material misstatements can result in fraud. Management fraud is a deliberate action by the management to mislead users of financial statements through preparation of materially misstated financial reports. These deliberate misstatements or omissions of amounts or disclosures of financial statements attempt to deceive users of financial statements, including shareholders, creditors, governments, and other stakeholders. There are two types of misstatements that can mislead investors and other users of financial statements. These two misstatements are “fraudulent financial reporting” and “misappropriation of assets” accompanied by misleading financial information. There are many types of fraud schemes including occupational fraud, in which employees defraud their employer, FSF, in which management defraud users of financial statements, and other frauds, including vendor fraud, supplier fraud, customer fraud, and digital fraud.

Fraudulent Misstatements

There are many ways in which misstatements can occur, and fraudulent financial statements can be committed, including (1) fictitious revenues, (2) timing differences, (3) concealed liabilities and expenses, (4) improper disclosure, (5) improper asset valuation, and (6) earnings management.

Fictitious Revenues

This scheme is used to overstate revenues during periods of financial distress and duress or to improve outlook for a given period. There are several ways of recording fictitious revenues, including false journal entries, inaccurate sales to existing customers, sales to fake customers, and round tripping. False journal entries typically take the form of a debit to accounts receivable and a credit to sales. This method is often supported by internally generated phony supporting documents to mislead auditors. Also, if other journal entries are not created to offset the imbalance created, auditors will easily identify the misbalanced accounting equation. Fictitious revenues can also be recorded by inaccurately accounting for sales to existing customers or by claiming sales to fake customers. Both schemes involve the forgery of documentation to support the fraudulent distortion of the financial statements. Forgery would be committed on documents such as sales invoices, shipping documents, and purchase orders.12 Similar to other revenue schemes, patterns exist, such as revenue at the end of a period, customers outside of the industry, and increasing sales with a drastic decrease in cost of goods sold. The same fraud detection techniques used under revenue recognition fraud can be used for this scheme too. Round tripping occurs when a transaction proves to be of little benefit but is recorded as if it were beneficial.13 According to the 2018 Report to the Nations by Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE), FSF schema had the greatest median loss at $975,000 per incident.14

Timing Differences in Revenue and Expense Recognition

The timing differences in revenue and expense recognition include the following schemes:

• Not matching revenues with expenses: The effect of this error overstates the net income of the company in the period in which the sales were recorded and understates net income when the expenses are reported.

• Early revenue recognition: The result of this not only leads to statement misrepresentation but also can serve as a catalyst to further fraud.

• Recording expenses in wrong period: The motivation of doing this comes from the pressures to meet budget projections and goods and lack of proper accounting controls.

Timing difference fraud, also known as cut-off fraud, includes the recognition of revenues before they were earned, postponing the recording of expenses and liabilities, and shipping merchandise to customers before the sale is approved or finalized. Under generally accepted accounting principle (GAAP), revenue is recognized when they are realized or realizable, when goods change ownership, or when services are rendered. The company could also keep the books open after the accounting period ends to accumulate more sales. The purpose behind these forms of fraud is, much like the previous form, to improve the apparent financial position of the company to encourage stock purchases, increase the availability of debt funding and decrease its cost, and to meet analyst forecasts of sales and net income. If the company of interest is avidly seeking funding through equity or debt, this could be a sign to carefully examine it for the aforementioned forms of fraud. Forensic accountants can uncover most forms of timing difference fraud by sampling a selection of transactions from the sales journal and inspecting the credit terms, comparing shipping documents and invoices for discrepancies, comparing invoice prices with published or established sales prices, or by simply verifying major sales. Forensic accountants can also look for increased shipping costs or decreased expenses near the end of the accounting period, indicating an irregularity that requires further assessment.15

Concealed Liabilities

Concealed liabilities, as the name suggests, involve hiding certain obligations from investors and the public to improve the apparent health of the company’s balance sheet similar to special purpose entities that were created by Enron to hide liabilities. Liabilities can be concealed by either hiding their existence or creating fictitious journal entries indicating that they have been paid down or paid off completely. A key component of financial health of a business is the leveraging of debt to generate returns. However, there is a delicate balance of debt-to-equity in every industry and it is not uncommon for businesses to be overburdened by debt. If this is the case, management may hide certain debt obligations that harm buy-ins to the company or reduce access to additional debt borrowing.

Companies that are in poor financial health, because of exorbitant amounts of debt, are likely suffocated by fixed costs associated with debt financing. If a company, struggling to pay bills as they become due, does secure additional debt funding by concealing liabilities, it only makes the fixed cost burden greater, thus making their financial position even more precarious than before. Liabilities could also be shifted from short term to long term to improve working capital figures, consequently increasing the apparent liquidity of the company. Liquidity, or solvency, is a key metric evaluated by creditors when making the decision to lend company money. Misclassification of the term of liabilities can be identified by identifying debt that was reclassified near the company’s fiscal year-end or in interim financial statements submitted to creditors with the purpose of obtaining additional debt funding.16

Improper Disclosure

The disclosure of financial and nonfinancial is crucial and often required by law such as SOX Act of 2002, SEC regulations and accounting standards. Disclosed information may include footnotes, nonfinancial key performance indicators (KPIs), and other important items located in public reports that could have an adverse effect on the company’s financial position. Disclosure schema include failure to disclose related party transactions, asset impairments, liabilities, and material departures from GAAP.17 Fraudulent behavior may frequently arise when the disclosures are manipulated to exclude pertinent information, mentioned earlier. This is often done by management to hide data that may dissuade investors from investing. If a subsequent event occurs after the balance sheet date but before the statements are filed, public companies are required to disclose the information if it is material.

The Sarbanes–Oxley (SOX) Act addresses many issues with disclosures to increase investor confidence in the accuracy and completeness of financial information of reporting by public companies. It has been noted by many experts that potential fraud schema can arise from the strict requirements of the SOX Act. Although less common, it is also possible that disclosures include fictitious or overstated benefits. For example, disclosing a harmful significant transaction in a positive manner to deceive investors, when the effect on the company’s financial health will be negative, is considered as fraud.

Valuation is the act of determining the intrinsic value of an asset. Improper asset valuation often involves the overstatement of an asset’s value, positively skewing earnings. The primary areas where improper asset valuation occurs are inventory, accounts receivable, and business combinations. Inventory can be overstated by falsifying physical count, and inflating its cost, among others. Accounts receivable is typically manipulated by either recording fictitious and related transactions in the accounts receivable, failure to write off uncollectible accounts, or manipulation of allowances for doubtful accounts. When a company acquires another business, it typically revalues its assets. The company could choose to falsely write up the assets to increase total asset value.18

There are several reasons for overvaluation fraud to occur. First, financial ratios are often used by investors to evaluate company performance. If the ratio is below the industry average or poor in comparison to previous years, investors are less likely to buy into the company. Also, certain debt covenants might be contingent on the company maintaining certain financial ratios. If the company falls below a contractually agreed-upon threshold, the creditor has the right to recall the debt and demand repayment in full. Management may intentionally overinflate assets to make ratios such as return on assets (ROA) appear better. Second, when more investors buy into a company, upper management may receive a bonus or the value of stock they own could increase. This is another incentive to erroneously report an asset’s or group of assets’ value(s).

Earnings Management

Earnings management is defined as a process of managing earnings to achieve the desired or targeted earnings. It can be done legitimately in creating sustainable performance, or in manipulating earnings. Earnings manipulation can be achieved by using accounting techniques to produce financial reports that present an overly positive view of a company’s business activities and financial position. Although accounting rules and standards often require management to make judgment calls, earnings management takes advantage of the gray areas of these standards and rules to inflate revenue and assets and manipulate liabilities and expenses.

Earnings management needs to be properly monitored after being implemented in a business. There are currently many methods a business can use to evaluate earnings. The methods usually fall under the purview of U.S. GAAP and therefore comply with accounting standards. These methods include inventory flow (e.g., first-in-first-out (FIFO), last-in-first-out (LIFO), and cost method), timing principles, estimates, and classification of earnings. These methods can conflict under certain circumstances and be used by management to manipulate earnings. For instance, when a company has financial statement items that are non-GAAP, they are excluded from earnings management. The reason for this is that the reconciliation of non-GAAP to GAAP standards can cause earnings management to become inaccurate and, in turn, a poor methodology for running a successful business.19

In summary, material misstatements in financial reporting can be classified into several categories. The first and most common scheme is the intentional manipulation of financial reports by management as discussed earlier. The second most common is the timing differences in revenue and expense recognition. The third category is concealed liabilities. The forth category is improper disclosures. The fifth category is improper asset valuation. The Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) released Auditing Standard (AS)2401 in 2003 and made amendments to the standard in 2015, which outlines the importance of this audit function when detecting FSF. During the audit, the auditor looks for fraud during financial statement analysis by assessing the risk of material misstatement and using the audit risk (AR) to establish the level of acceptable materiality and detection risk. The lower the acceptable detection risk to the auditor, the more the procedures required to verify the validity of audit evidence.20 On December 15, 2012, Au-C section 240 became effective. This standard, established by the AICPA, is similar in nature to AS 2041 released by the PCAOB. It requires the auditors to consider the possibility of management committing FSF. The standard also lays out auditor’s responsibilities, requirements, and objectives.21

The most commonly used method for concealing liabilities/expenses is through liability/expense omissions because it is easy not to record liabilities and expenses, which makes it more difficult to discover the related fraud. Perpetrators of liability and expense omissions often plan to conceal their fraud until it can be compensated with future sources of income. For example, by increasing the sale price in the future when the omitted expenses can be recorded. These types of fraud can be prevented through effective internal controls and can be discovered through abnormal changes in accounts payable by recording unusual transactions in the postfinancial statement date.

Fraud can be committed by intentionally overstating inventory by falsely increasing inventory value and decreasing cost of goods sold. The fraud perpetrator can conduct the fraud of overstating inventory. An effective inventory internal control system using just-in-time and perpetual system can prevent fraudulent inventory overstatements. Four types of tools to discover fraud include inventory physical counting, review of accounts receivable, aging report, and analytical procedures. Inventory counting involves using inventory scanners, physical counts, and inventory logs to compare estimated count with actual inventory count. Massive discrepancies can indicate inventory fraud. Accounts receivable is an account used to measure sales that have been completed but of which payment has not been received yet. Reviewing accounts receivable can determine if sales were recorded when the transaction(s) were not completed. An aging report is a methodology applied to accounts receivable that determines “how long” or the useful life of account receivable. The older the receivable, the less likely it is to be collected and thus, more allowance for uncollectible/doubtful accounts should be considered. Analytical procedures allow for in-depth analysis of factors that can impact inventory, cost of goods sold and accounts receivable.

Asset misappropriation, usually pertaining to occupational fraud, involves the theft or misuse of the organizations’ assets and can be conducted by any employee, including management and even nonemployees. However, employees are usually the perpetrator of asset misappropriations, whereas management typically engage in FRF, including asset misappropriations. The four current classifications of asset misappropriation are cash schemes, accounts receivables, inventory, and fixed assets schemes. These are discussed in the following paragraphs.

Cash schemes include skimming, larceny, and fraud cash payments. Skimming is defined as removing cash from company hands before it enters into the record books (accounting software). This fraudulent behavior often affects the revenues/sales account and checkbooks. Cash larceny is the theft of money from an employer without consent of the employer and the intension to give back. Lastly, fraudulent cash payments occur when an employee (usually in a management position) disburses cash to others unrelated to the business dealings. Examples of this type of scheme include payroll alterations, check forgery, and unrelated business expense reimbursement. This type of scheme is also the most prevalent form of asset misappropriation.

Accounts receivable is also subject to varying degrees of fraudulent behavior. The types of schemes prevalent to accounts receivable are lapping, made-up receivables, and posting unnecessary credits. First, lapping is recording a payment twice or recording another payment after the money was already received. Relating to fictitious sales mentioned in the previous paragraph, fictitious accounts receivables are only created to match phony and fake sales account. The reason for this is most businesses use the accrual accounting system, which records a debit to receivable and credits sale revenue when a revenue transaction has occurred not when a cash collected. Finally, the improper use of discounts, returns, and allowance for uncollectible accounts is often misused. An employee can manipulate an account as it was written off and then pocket the money for personal use.

Inventory fraud schemes happen in many types and sizes of retail and manufacturing companies, particularly in big warehouses of various businesses. The most common schemes are inventory theft, selling scrap, and use of inventory for one’s personal use. The final category of asset misappropriation is fixed asset schema. This is the manipulation of a company’s property, plant, and equipment, usually for personal use or gain. Theft of smaller equipment such as drills, hammers, and other lightweight objects is frequent.22

Employee fraud is committed by employees other than owners and executives. Employees are much more likely to commit fraud according to ACFE’s 2016 Report to the Nations.23 The median loss attributed to employee occupational fraud was $65,000, the median loss for managers was $173,000, and the median loss for owners/executives was $703,000. The reason for the high disparity in the dollar amounts is due to executives being able to bypass and control functions of the corporation, allowing them higher opportunities for fraudulent activity. The losses were also attributable more to males than to females. Out of the 2,410 cases analyzed by the ACFE, males contributed a median loss of $187,000, whereas females contributed only $100,000.24 In the past 3 years, there was about 10 percent increase in median loss for females and a 6.5 percent decrease for males. When comparing positions held in the company, the gender breakdown between males and females matches the overall losses stated earlier. Owners and executives of both genders were more likely to steal more from the company. When fraud is broken down by schema, males engaged in FSF and corruption, whereas females engaged more in asset misappropriation. For both genders, as age increased, so did the frequency of fraud. Also, the higher the level of education, the more likely an employee is to commit fraud. Overall, 82.5 percent of perpetrators are never punished for their actions.25

A key component to analyze regarding employee fraud is the method of detection used. The three most common detection methods were tips, management reviews, and internal audits with the average of 36.55 percent, 13.6 percent, and 15.3 percent, respectively.26 Across the regions of the United States, South Africa, Asia-Pacific, and Latin America and the Caribbean tips were the highest surveying in at 37 percent, 37.3 percent, 45.2 percent, and 36.9 percent, respectively. The average for all four regions is 39.1 percent. Management reviews in all four regions, polled in at 14.3 percent, 10.2 percent, 13.1 percent and, 17.1 percent, respectively, for an average of 13.68 percent. Lastly, internal audit detection across all four regions sampled at 14.1 percent, 16.2 percent, 15.8 percent, and 19.8 percent, correspondingly, for an average of 16.48 percent. These methods differed between size of firm, confession, management review, and surveillance. Larger firms preferred tips and internal audit, whereas smaller firms favored external and minor internal activities such as external audits.27

Employee fraud can be prevented and detected in many ways as follows:

1. Sound code of conduct: A proper and effective code of conduct for employees promotes a corporate culture of integrity and competency. The code of conduct should provide guidelines for ethical behavior and accountability.

a. The ACFE states in their Code of Ethics that any illegal activity or activity that leads to a conflict of interest between parties is strictly prohibited. This standard adheres strictly to professionalism, which is a positive quality associated with one’s business career. It is also important for a CFE to remain a confidant in all times throughout his or her career. Accounting ethics strongly supports the foundational pillar of accountability and confidentiality.28

2. Implementing an effective system of internal control and establishing a system of checks and balances in preventing employee fraud: An effective system of internal control should prevent, detect, and correct any errors, irregularities, and fraud.

3. Policies and procedures in observing employee’s behavior: Employees tend to be more ethical when they know there is an accountability system that monitors their behavior and actions without invading their privacy.

Identifying and Gathering Evidence

Evidence identification, gathering, and evaluation during legal matters and independent investigations are crucial. This section discusses various services that can be performed by forensic accountants and the type of evidence they need to gather to effectively support their decisions to be able to defend in the court of law. Forensic accountants need to know where evidence (paper and electronic) can be found and how it should be evaluated and processed. For example, more credible and persuasive materials need to be gathered for fraud allegations regarding revenue manipulation because the majority of FSF cases involved improper revenue recognition even though revenue manipulation could be the most expensive form of earnings management. Revenue manipulation is the most common type of FSF, even though it can be very costly because of the higher likelihood of receiving comment letters from the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), short interest, restatements, increased audit fees and unfavorable audit reports, litigation, investigations, sanctions by regulators and standard setters, and negative market reactions.

Management is also responsible for cash flows generated from operating, financing, and investment activities because cash flows determine stock prices, firm valuation, and debt-service capacity, eventually influencing costs of capital. Manipulation of cash flows from operations is most common. For example, management can manipulate cash flow by classifying operating leases as capital expenditures that could shift the payments from the operating section of the cash flow statement to the investing section.

Rules and Types of Evidence

Evidence can be defined as things, matters, or issues—physical, verbal, or electronic—that can be relevant in an investigation to support assertions, propositions, or factual statements. The rule of evidence is whether a case is held before a judge or a jury or whether it is presented in court. There are two general categories of evidence. First, the direct evidence that provides the existence of a fact under investigation without any need for inferences or presentation of any other facts. Circumstantial evidence is the evidence that requires an inference on the basis of indirect evidence. Each of these two categories of evidence can be further classified into testimonial, demonstrative, and real evidence.

Testimonial evidence is an oral declaration of fact or a written statement by witness that is used in trial. This witness could be involved in the subject of litigation, to an extent, or could be an expert witness hired to provide credible testimony regarding a matter requiring specialized knowledge. These witnesses are typically subject to cross-examination by the opposing side. The aim of the cross-examination would be to discredit the individual’s testimony or credibility within the circumstances of the case.29

Demonstrative evidence, by definition, includes all evidence that is not substantive or testimonial in nature. This form of evidence is often meant to demonstrate or represent testimonial evidence in a physical form and is only admissible when it precisely mirrors the witness’s testimony. Examples of this type of evidence are pictures, charts, and objects that can be used in litigation to support the case. Demonstrative evidence can be immensely useful when testimonial evidence is complex in nature, because it can provide a visual representation of the facts that can be more easily understood by a jury.30

Real, or physical, evidence simply relates to any object used in trial and litigation. It is similar to demonstrative evidence in the sense of its physical nature; however, this form of evidence is not generated from testimony. Real evidence can include an alleged murder weapon, narcotics, fingerprints, clothing, or any material object used to prove or disprove an issue in a trial. An important concept relating to real evidence is its chain of custody. This describes the chronological possession of the evidence, aiming to reduce the chance of admitting tampered or contaminated evidence into the trial.31

Evidence-Gathering Procedures

Forensic accountants perform a variety of investigative, litigation, and expert witnessing services for their clients that range from a simple asset valuation to a more complex fraud and dispute investigation. Regardless of the type and complexity of the engagement, forensic accountants should do the following steps of planning and preparation, evidence gathering and evaluation, and conclusions and communication.

Planning and Preparation

Forensic accountants should plan the engagement by deciding to accept the engagement, evaluate the client, obtaining an understanding of the engagement case, assess their resources and ability to perform the service, and the commitment to do thorough investigation. The decision to accept the client is extremely important, particularly in the case of expert testimony and requires proper negotiation and understanding of the scope of forensic accounting services. Forensic accountants should obtain either verbal or written agreement from their client before performing the service. Terms of the agreement should be specified in the engagement letter. During the planning stage, forensic accountants should consider the factors that increase the likelihood of FSF. These factors should be addressed and considered in planning an investigation absolute power, greed, incompetence, capability, pressures/incentives, opportunity, collusion, and lack of proper business codes of conduct. Factors that may decrease the possibility of FSF are effective corporate governance; compliance with applicable laws, rules, regulations, and standards; effective internal controls; and tone at the top.

Gathering Evidence, Reporting, and Court Proceedings

After the engagement has been planned, the forensic accounting team must gather evidence. In the current forensic landscape, there are various procedures that can be used to gather sufficient, accurate, reliable, and timely evidence. These procedures include testing controls, which can be used to identify security loopholes, and analytical procedures to conduct trend or comparative analysis. This will enable accountants to detect paradigms or cycles on a business using advanced computer techniques and software, interviewing, and reconciliations. The aforementioned processes will allow enough evidence to be gathered to report to the client. The report includes the fraud scheme and information supporting the schema. This report is used in court proceedings as evidence to determine the guilt, or lack therefore, of the defendant.32

Evidence-Gathering Methods

Brainstorming Sessions

Mind-mapping, open-ended, computer-mediated, and strategic reasoning are the four types of brainstorming techniques, according to the Tennessee Society of CPAs (TSCPA).33 These methods each involve the forensic team holding meetings to create means to interact with fraud.34 Opened-ended brainstorming involves practitioners selecting an arbiter that allows the free flow of ideas. A notetaker is present and is not allowed to participate in the discussion. This technique has a shortcoming though; not all ideas may be heard because of time constraints and number of individuals speaking per session. In relation to fraud, this technique is frequently cited has discovering fraud risk factors at a higher rate.

Computer-mediated brainstorming is the use of a computerized environment to simulate face-to-face interaction via electronic transmissions. Examples of this technique include telecommunications, Skype, and Blue Jeans. Electronic data transmission allows quicker exchange of information when compared with other methods. It also allows for anonymous transfer of information, if necessary. Mind-mapping is real-time diagramming placing the discussion title in the center and major elements branch from the center. This approach is evidence of the use of visualization technologies, which are becoming more prevalent as data sizes increase (Big Data). Both computer-mediated and mind-mapping uses software such as XMind, iMindMap, and StormBoard to host these visualizations and communication networks. Lastly, strategic reasoning evaluates how managers commit fraud. This perspective enables auditors to think in the shoes of management when conducting an audit and looking for fraudulent behavior.35

Red Flag Identification

Red flags are defined the early symptoms that would indicate a higher risk of potential fraud or intentional misstatement of financial statements. Forensic accountants can assess fraud by focusing on using fraud risk factors, “red flags,” to assess the overall risk of fraudulent financial reporting as suggested in SAS No. 99.36 In this approach, the forensic accountant identifies the presence or absence of certain red flags and then assesses the risk of fraud. To facilitate the use of red flags, various decision aids have been developed, such as checklists, regression models, and expert systems. One major limitation of current red flag approaches is that they are developed to assess the overall fraud risk without considering the impact of fraud schemes that are used by management to perpetrate and conceal fraud.

A checklist consists of a list of potential red flags that the auditor can use to assess fraud risk. Various decision aids have been developed, including checklists, regression models, and expert systems to facilitate the use of red flags. A checklist consists of a list of potential red flags or sympathies that forensic accountants can use to assess fraud risk. Checklists are the most common decision aid for forensic accountants. One major drawback of the checklist is that it ignores the structure and interrelations between fraud risk factors.

Examples of red flags checklists of FSF are:

• Personal financial pressure

• Vices (e.g., drugs, alcohol, or gambling)

• Extravagant lifestyles

• Real or imagined grievances against company

• Related parties

• Increased stress

• Internal pressures

Red flag lists are often used to spot and warn about fraudulent activity by degree of severity. A red flag is defined as a circumstance that is outside the norm. There are several categories of red flags that can enable forensic accountants to identify and detect errors, irregularities, and fraud. These categories include:

• Employee red flags: Can be identified by changes in expenses, turnover, working overtime frequently, or lack of separation of duties. For example, if an employee buys a Porsche not affordable with the salary made in the position held, this is an employee red flag.

• Management red flags: Signs include noncompliance with accounting standards and policies, lack of internal control environment, too many bank accounts, decisions made by a select few managers, too many year-end transactions, or nonresponses and waiver of auditors suggested adjustments and closing entries.

• Change in behavior red flags: This category can apply signs including borrowing money from coworkers, excessive drinking or other negative habits, carrying unusually large amounts of cash, overworking, or gambling beyond reasonable means.

Statistics have been released that enable forensic accountants and auditors to search for specific red flags. An overwhelming 42.1 percent of occupational fraud violations are committed by employees and 61 percent of fraudulent actions were perpetrated by males. Despite these statistics to help narrow down red flags, 88 percent of individuals who commit fraud are never caught by the legal system.37

Regression Models

The most common regression models are linear and logistic. Different model selections can be used with these regression types, including backward, forward, and stepwise. Regressions are often used to perform statistical analysis on data sets, in which relationships among input and target variables must be discovered. There are many software providers that produce software that aids in regression modeling. An example of regression software is SAS Enterprise Miner.38

A logistic regression model can be used in fraud detection by analyzing a company’s financial information in a model to identify irregularities and anomalies for further inspection. For example, the timing of a company’s journal entries could be examined using a linear regression model, where the relationship between number of journal entries of a specific category and time are analyzed. If the number of journal entries in specific accounts with a high propensity for fraud increases drastically at year-end, forensic accountants would be alerted to closely inspect that specific account for potential fraud. A predictive model can be used in a similar fashion by using historical data to project certain financial ratios. If the projected ratios are drastically different from the ratios on financial statements, that would be an indication for the auditor to see if the over- or underperformance caused by fraud.

Expert System Aids

Expert system aids are commonly computer-based design consultation systems that verify completeness, consistency, and accuracy of transactions or events. These computer-based expert system aids are often used to mimic the decision-making process and reasoning capabilities of the human mind. Forensic accountants can use expert system aids to increase the efficiency and accuracy of their work. Expert systems mimic the auditors’ and forensic accountants’ professional judgment to arrive at similar conclusions as the human. These systems are fed large amounts of test data and professional knowledge and reduced to “if-then” rules to build a basis for decision making and analysis. As expert systems have progressed over time, they are capable of processing increasingly complex issues and providing thorough solutions, similar to that of a human expert. The benefit of expert systems from a fraud detection standpoint is that forensic accountants are able to analyze 100 percent of the data in the area of interest to detect anomalies, in a significantly shorter amount of time.39

Analytical Procedures

Analytical procedures are techniques used by forensic accountants and auditors in gathering and evaluating evidence by studying plausible relationships between financial data and their link to nonfinancial data. Analytical procedures can be an effective tool for forensic accountants in all phases of an investigative engagement, including the planning phase of deciding on the extent and types of tests, in substantive testing of gathering and evaluating evidence, and in the overall review of an investigation in justifying results and opinions. Like auditors, forensic accountants can perform analytical procedures during the planning stage of the investigation to enhance understanding of the client’s business and to assist in planning the nature, timing, and extent of their testing. During the planning stage, analytical procedures are typically performed by comparing financial data with nonfinancial data and developing expectation for the investigation. Forensic accountants’ expectations should be developed through a comprehensive understanding of the client and its industry and knowledge of the client’s financial and internal control systems. Forensic accountants may use several sources of information to develop expectations, including financial information from prior periods, nonfinancial information (client standing in the industry with peers, management style, and integrity), anticipated results (budgets or forecasts), information on the industry in which the client operates, and the relationships of financial information with nonfinancial information.

Financial ratios are often used to detect FSF. Research from the past 30 years has shown that specific ratios are more useful at fraud detection than others. The ratios of total debt-to-total assets (TD/TA), total liabilities-to-total assets (TL/TA), total debt-to-equity (TD/E), current assets-to-current liabilities (CA/CL), and working capital-to-total assets (WC/TA) have proven to be most effective in establishing relationship among financial data. Managers have more incentives to commit FSF when liquidity is low, and that the above-mentioned ratios aid in determining liquidity of a business. Financial ratios are typically classified into profitability, solvency, and operating ratios that enable forensic accountants to detect financial anomalies and items that are out of norm.

Scanning is an eye-open approach looking for unusual items and is considered as analytical procedure that relies on the professional judgment, which has been developed through education and work experience, to identify suspect items during an audit or a forensic investigation. These can include overstated or understated accounts, new accounts, and balances that are high or too low in comparison with the industry average.40 A combination of financial ratio analyses, scanning, and time-series analyses can enable forensic accountants to identify unusual items and anomalies. For example, if a company has historically grown 5 percent annually, managers could be under pressure to misstate financial statements if the internally expected growth is less than 5 percent. Additionally, analyst projections can exacerbate the pressure felt by management, as often when the consensus of analyst projections is not met, the company is punished by the market with a fall in stock price.41 A comparison of financial data with nonfinancial KPIs such as budgets can assist forensic accountants to establish benchmark for assessing management expectations and incentives.

Financial reporting analysis techniques can help detect FSF. The first is vertical analysis for analyzing the relationships between the items on an income statement, balance sheet, or statement of cash flows by expressing components as percentages. This method is often referred to as “common size” financial statement analyses. In the vertical analysis of an income statement, net sales are assigned 100 percent; for a balance sheet, total assets are assigned 100 percent. All other items in the financial statements are expressed as a percentage of these numbers. It is the expression of the relationship or percentage of component part items to a specific base item. Vertical analysis emphasizes the relationship of statement items within each accounting period. These relationships can be used with historical average to determine statement anomalies.

The second type is horizontal analysis, also known as “trend analysis,” to determine changes (increase/decrease) in a series of financial data over a period of time expressed as either an amount or a percentage commonly over several years. The third type is ratio analysis, which is the study of relationship among financial items. Traditionally, financial statement ratios are used in comparison to an entity’s industry average or other norms in identifying red flags of FSF.

Benford’s Law

Benford’s law, founded by Simon Newcomb, uses the occurrence of digits to show a trend.42 The law compares the actual frequency of the digits in a data set, using a digit-by-digit approach. This output is compared with the expected occurrence to find holes in data. The deviations in the frequency are then investigated. For example, a forensic accountant may use Benford’s law to spot fraud in an assigned case. The forensic accountant uses the standard Benford curve to identify an area for further investigation.

A Benford curve resembles an exponentially decreasing function, as it increases toward the y-axis and decreases as it moves away. Benford’s law states that the number 1 will be the leading digit in a set of numbers approximately 30 percent of the time and the following numbers have a proportionally less chance of appearing as a leading number, relating to their respective order. A comparison between actual results and expected results can be analyzed simply by comparing graphs of the two. If the actual results do not approximately line up with the Benford curve, further investigation is needed. If a forensic accountant examines a large data set and finds that the number 1 is the leading digit only 8 percent of the time, it could be an indication that the data set is not genuine and fraud could be present.43

Artificial neural networks (ANNs) are computer scientists’ attempts in mimicking the thought process of a human brain in technology, which has proven success in detecting and preventing credit card fraud. The revolutionary feature of ANNs is their ability to model linear and nonlinear relationships, learn these relationships directly from the data being used, and apply them to future situations. Consequently, ANNs can be used as a tool in fraud detection, such as creating expectations for account balances that can be compared with actual balances. Previously used fraud detection systems would determine fraudulent events on the basis of a predetermined and static pattern; however, ANNs can gauge a transaction’s variance from the pattern to determine a more accurate determination if the transaction is fraudulent.44

Forensic Data Analytics

Data analytics is the process of identifying, mapping, cleaning, examining, analyzing, and converting a set of raw data into formatted and useful information for decision making. This process is often conducted using specialized systems and software. Business organizations have increasingly used data analytics processes, techniques, and technologies as a decision aid to make more-informed business decisions. In recent years, Big Data analytics are employed to study and investigate large amounts of data to discover patterns, correlations, and other insights in the database as descriptive, predictive, or prescriptive modeling and analyses. Forensic data analytics help organizations by preemptively preventing fraud, improving internal controls, improving the regulatory and compliance environment, and controlling the degree of fraud reactively. Forensic data analytics provide forensic accountants with the predictive tools to deter FSF and establish fraud-protection solutions rather than attempting to manage damage after it has occurred.45 The concept of Big Data and data analytics has been around for many years to capture and transform huge data into a set of manageable and useful information for decision making. Forensic accountants can use Big Data and data analytics to:

1. Discover patterns among data.

2. Connect the dots in discovering fraud.

3. Store large amounts of data.

4. Analyze new sources of data.

5. Effectively and efficiently, discover fraud.

The application of Big Data and data analytics to forensic accounting is currently at an early stage of initiation and development and forensic accountants have taken a scattershot approach in addressing capabilities of Big Data in identifying patterns in financial and nonfinancial information in annual and quarterly financial reports, management discussion and analysis (MD&A), and management earnings forecast. Forensic analytics is powerful enough to be used singularly, or alongside the practices of investigations, audits, and process review, and with such a large amount of data flowing in, forensic data analysis can be used to transform raw data into intelligible information.46 It is expected that Big Data will grow bigger, and thus, forensic accountants should proactively search for patterns, including irregularities in Big Data, and assess and manage their risk profile in detecting fraud.

Forensic accountants can use Big Data, which has the capability to store huge amounts of data, and data analytics, the algorithms through which data are transformed to information, as valuable evidence. The use of both Big Data and data analytics is changing the way forensic accountants gather and assess evidence in their investigation and in discovering fraud. This affects planning, evidence gathering, and reporting phases of a forensic investigation. During the planning phase, forensic accountants should make sure to adopt some of the new tools that enable them to take full advantage of Big Data and data analytics. Forensic accountants should change their way of making decisions to take advantage of analytics. Building a foundation of Big Data and data analytics into the investigation process is now possible because of the new tools available. Forensic accountants have a wider set of options to use computerized-assisted investigation tools and techniques to perform descriptive and predictive analytics on Big Data in detecting fraud and providing early signals of fraud. The scale and complexity of Big Data, however, requires advanced levels of analytical skills by forensic accountants for data mining, deriving algorithms, and predictive analytics.

In summary, analytical procedures with the use of ratio analysis is the most conventional approach used in detecting fraud, despite its subjectivity in selecting the ratios that are likely to indicate fraud.47 Data mining is another technique that can discover the implicit, previously unknown and actionable knowledge and include techniques such as logistic regression, neural networks, decision trees, and text mining. Time-series and regression analyses can be used to identify critical risk factors, financial and nonfinancial, and develops a regression model combining these factors to predict fraud. Expert systems, by incorporating judgment of auditors during the fraud risk assessment process, perform better than checklists or regression models.

Conclusion

In performing forensic accounting services of fraud investigation, expert witnessing, and litigation consulting, forensic accountants investigate allegations of wrongdoing such as FSF, employee fraud, kickbacks, bribery, conspiracy, inside trading, valuation disputes, and money laundering, among other forensic accounting services. It is important for forensic accountants to understand the role of evidence, methods of gathering sufficient and competence evidence, evaluate evidence, reach conclusions, communicate findings, write a report, make recommendations, and testify before courts. This chapter discusses fundamentals of forensic accounting, including types of evidence (i.e., direct and circumstantial), evidence-gathering procedures, evidence assessment, risk assessment, internal control evaluation, reach conclusions, express opinions, make recommendations, and testimony by the court.

Action Items

1. Rules of evidence determine whether evidence is permissible into various types of judicial and administrative proceedings.

2. Evidence is all things, matters, and issues relevant to the matter under investigation.

3. Evidence can be direct or circumstantial, physical, documentary, and verbal.

4. Evidence-gathering procedures are all methods of gathering sufficient and competent evidence.

5. Evidence should be used in forming an opinion and reaching conclusions.

6. Recommendations should be made on the basis of evidence gathered and opinion expressed.

Endnotes

1. Ernst and Young (EY). 2016. Global Forensic Data Analytics Survey 2016. Shifting into Higher Gear: Mitigating Risks and Demonstrating Returns. http://www.ey.com/gl/en/services/assurance/fraud-investigation---dispute-services/ey-shifting-into-high-gear-mitigating-risks-and-demonstrating-returns, (accessed January 4, 2017).

2. American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). 2018. Exposure Draft: Statement on Standards for Forensic Services No. 1 (SSFS 1). Available at https://www.aicpa.org/interestareas/forensicandvaluation/resources/standards/exposure-draft-statement-on-standards-for-forensic-services.html

3. ACFE. 2018. Planning and Conducting a Fraud Examination. http://www.acfe.com/uploadedFiles/Shared_Content/Products/Books_and_Manuals/2018%20US%20FEM%20Sample%20Chapter.pdf, (accessed December 10, 2017).

4. D. Cressey. 1953. Other People’s Money: A Study in the Social Psychology of Embezzlement (Glencoe, IL: Free Press).

5. American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). 1997. Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit. SAS No. 82 (New York, NY: AICPA).

6. AICPA. 2002. Statement on Auditing Standards (SAS No. 99): Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit (November) (New York, NY: AICPA).

7. D.T. Wolfe, and D.R Hermanson. 2004. “The Fraud Diamond: Considering the Four Elements of Fraud”, The CPA Journal 74, no. 12, pp. 38–42.

8. M. Hossain, S. Mitra, and Z. Rezaee. October, 2016. “Can Capital Punishment Deter Financial Reporting Fraud,” Advances in Financial Planning and Forecasting (AFPF), pp. 15–25.

9. Z. Rezaee, and B. Kedia. 2012. “The Role of Corporate Governance Participants in Preventing and Detecting Financial Statement Fraud,” Journal of Forensic and Investigative Accounting 4, no. 2, pp. 176–205.

10. Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO). 1999. Fraudulent Financial Reporting: 1987–1997, an Analysis of U.S. Public Companies (New York, NY: AICPA).

11. Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO). 2010. “Fraudulent Financial Reporting: 1998–2007: An Analysis of U.S. Public Companies.” www.coso.org

12. Wells, J.T. 2001. “Follow Fraud to the Likely Perp,” Journal of Accountancy 191, no. 3, pp. 91–94. https://www.journalofaccountancy.com/issues/2001/mar/followfraudtothelikelyperp.html, (accessed September 11, 2018).

13. J. Ahmad, D. Jansen, and J.J. Frank. May, 2003. “Common Financial Statement Fraud Schemes,” Yale University.http://faculty.som.yale.edu/shyamsunder/FinancialFraud/Frank-Common%20Financial%20Fraud%20Schemes%207May%2003v1.doc

14. ACFE. 2018. Report to the Nations. https://www.acfe.com/rttn2016/costs.aspx

15. J.T. Wells. 2001. “Timing Is of the Essence,” Journal of Accountancy. https://www.journalofaccountancy.com/issues/2001/may/timingisoftheessence.html, (accessed September 12, 2018).

16. ACFE. 2018. Common Financial Statement Frauds. https://brisbaneacfe.org/library/third-party-fraud/common-financial-statement-frauds/

17. Deloitte. 2009. Sample Listing of Fraud Schema. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/in/Documents/risk/Corporate%20Governance/Audit%20Committee/in-gc-fraud-schemes-questions-to-consider-noexp.pdf, (accessed September 13, 2018).

18. ACFE. 2016. Financial Transactions and Fraud Schemes. http://www.acfe.com/uploadedFiles/ACFE_Website/Content/review/examreview/12-accoutning-concepts.pdf, (accessed September 13, 2018).

19. J. Ronen, and V. Yaari. 2008. Earnings Management: Emerging Insights in Theory, Practice, and Research. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-0-387-25771-6.pdf

20. PACOB. 2015. AS 2401: Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit. https://pcaobus.org/Standards/Auditing/Pages/AS2401.aspx

21. AICPA. 2012. AU-C Section 240. https://www.aicpa.org/Research/Standards/AuditAttest/DownloadableDocuments/AU-C-00240.pdf

22. ACFE. 2011. Introduction to Fraud Examination. https://www.acfe.com/uploadedFiles/Shared_Content/Products/Self-Study_CPE/intro-to-fraud-exam-2011-extract.pdf

23. ACFE. 2016. Report to the Nations on Occupational Fraud and Abuse. http://www.acfe.com/rttn2016.aspx, (accessed March 14, 2018).

24. Ibid.

25. Ibid.

26. Ibid.

27. ACFE. 2016. Report to the Nations. https://www.acfe.com/rttn2016/docs/2016-report-to-the-nations.pdf, (accessed October 21, 2017).

28. ACFE. 2017. ACFE Code of Professional Ethics. http://www.acfe.com/uploadedFiles/ACFE_Website/Content/documents/Code-Of-Ethics.pdf, (accessed October 21, 2017).

29. Cornell. Legal Information Institute. https://www.law.cornell.edu/

30. Ibid.

31. ACFE. 2016.

32. ACCA. 2018. Forensic Auditing. http://www.accaglobal.com/us/en/student/exam-support-resources/professional-exams-study-resources/p7/technical-articles/forensic-accounting.html

33. Tennessee Society of CPAs (TSCPA). June, 2015. Conducting Effective Fraud Brainstorming Sessions. https://www.tscpa.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/cpe_fraudbrainstorm_mayjune2015.pdf?sfvrsn=2

34. Ibid.

35. Ibid.

36. AICPA. 2002.

37. T.P. DiNapoli. n.d. Red Flags for Fraud. https://www.osc.state.ny.us/localgov/pubs/red_flags_fraud.pdf

38. SAS. 2017. How It Works. https://www.sas.com/en_us/insights/analytics/predictive-analytics.html

39. L.M. Smith. 1994. “Accounting Expert Systems,” The CPA Journal Online. http://archives.cpajournal.com/old/16458936.htm, (accessed September 17, 2018).

40. AICIPA. 2017. AU-C Section 520: Analytical Procedures. https://www.aicpa.org/Research/Standards/AuditAttest/DownloadableDocuments/AU-C-00520.pdf

41. R. Kanapickiene, and Z. Grundiene. 2015. The Model of Fraud Detection in Financial Statements by Means of Financial Ratios. https://ac.els-cdn.com/S1877042815059005/1-s2.0-S1877042815059005-main.pdf?_tid=8312b854-0b54-11e8-a8c5-00000aab0f26&acdnat=1517932004_f34c411fb7391be5aef7c5d940699e39

42. J.C. Collins. April 1, 2017. “Using Excel and Benford’s Law to Detect Fraud,” Journal of Accountancy. https://www.journalofaccountancy.com/issues/2017/apr/excel-and-benfords-law-to-detect-fraud.html

43. Ibid.

44. R. Patidar, and L. Sharma. September 18, 2018. “Credit Card Fraud Detection Using Neural Network,” International Journal of Soft Computing and Engineering. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/0419/c275f05841d87ab9a4c9767a4f997b61a50e.pdf

45. Ernst Young. 2013. Forensic Data Analytics. https://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/EY_-_Forensic_Data_Analysis/$FILE/Forensics-Data-Analytics.pdf

46. Ibid.

47. C.E. Hogan, Z. Rezaee, R.A. Riley, and U.K. Velury. 2008. “Financial Statement Fraud: Insights from the Academic Literature,” AUDITING: A Journal of Practice and Theory 27, pp. 231–52.