THE CHANGING DYNAMIC OF INSTITUTIONAL CARE

The Western Counties Idiot Asylum 1864–19141

I

There have been at least two consequences of the much publicised closure of the long-stay hospitals for people with mental handicap or learning disability that has taken place over the past decade. The first has been a concern with the effectiveness or adequacy of community care for those discharged from the long-stay institutions: media headlines and more scholarly research have both drawn attention to the ‘holes in the net’ and the shortcomings of both policy and practice. The second has been to stimulate an interest in the history of institutional care. It is this aspect which this chapter seeks to explore.

This chapter examines the five voluntary institutions for idiots founded in England in the twenty-year period between the late 1840s and the late 1860s. Regionally dispersed, they represented the main institutional provision specifically for people with learning disabilities and were, along with smaller private establishments, Poor Law workhouses and the county lunatic asylums, an important short- or long-term alternative to family care. The second section of this chapter looks at selected aspects of this charitable enterprise; the third and fourth sections more specifically examine the experience of the Western Counties Idiot Asylum at Starcross near Exeter, in the fifty years between its foundation and the outbreak of the First World War. ‘The historian may observe the institutions from a distance and note remarkable similarities between them: under the microscope the differences are equally striking.’2 The Western Counties Asylum was similar in many respects to its counterparts in other parts of the country. But its principal distinguishing feature was its developing reliance on Poor Law-funded patients; a factor which, it is suggested here, owed much to the Institution’s continuing search for financial viability and security as well as to the original conception and aims of its founders.

Despite the aura which continues to surround them, public institutions have had a comparatively short history. They have only been part of our welfare history in Britain for the past 150 years. Private madhouses, gaols and parish workhouses, of course, had all existed before the nineteenth century. But it was the nineteenth century itself – with its national system of Poor Law workhouses, the construction of lunatic asylums, the beginning of long-stay hospitals for the mentally handicapped and the development of ‘model’ prisons – that conceived and implemented the institutional panacea. That fact is reflected in the increase of buildings, their scale and size and the number of inmates they housed. Its legacy has been a persisting negative image of residential establishments which has been reinforced by reported cases of the abuse of inmates, the enforced association and routine of institutional life and the compulsion often associated with entry as well as with subsequent detention.

If that largely negative image of residential establishments has ‘embedded itself in popular consciousness’,3 it has also been an important theme in the sociological and historical writing on institutions. This is symbolised especially by Goffman’s discussion of the ‘total institution’,4 Foucault’s writing on the ‘structures of confinement’5 and Scull’s analysis of the ‘capture of the mad’ by the emergent medical profession. Once asylums were established they represented ‘a culturally legitimate alternative, for both the community as a whole and the separate families which made it up, to keeping the intolerable individual in the family’.6 According to this analysis asylums came to represent a dumping ground for deviants where, within a closely regulated and separate community, a controlling environment – be it physical or psychological in nature – was established.

More recent research, focusing on patterns of admission and discharge as well as average length of stay, has called into question the ‘total’ nature of the nineteenth-century institution.7 It has also concentrated much more on the dynamics of the institution: the relationship between its component system of management and administration, and in the case of the voluntary asylums, the philanthropic committees, the Superintendents, the staff of attendants and the inmate population; the pattern of admission and discharge; the nature of the inmate experience – in education, training and recreation; the changing legal framework within which the asylums operated and the shifting discourse on mental deficiency in Victorian and Edwardian England which moved from a conscientious commitment to individual improvement to a fin de siècle pessimism redolent with images of degeneration.8

Such an agenda necessarily represents an attempt to reconstruct the public and private life of the voluntary asylums. For its sources it depends mainly on printed materials such as relevant Parliamentary Papers and Royal Commissions, Reports of the Commissioners of Lunacy, the Annual Reports, Committee Papers, correspondence and case notes of the institutions themselves (where these have survived) as well as other documentary sources such as local newspapers and, where they still remain, the evidence of the buildings and their physical layout. For more recent times these sources can, of course, be complemented by interview material from residents and their relatives, staff of all grades, managers and administrators and members of the local community. But the questions which such research is especially required to address concern the increasing scale and size of such institutions and the ways in which such growth impacted upon their internal structure and regime.

Those research questions I suggest need to address first of all the interrelationship of national legislation and local practice. On the one hand the institutions grew and changed because of the changing definitions in the legislation of those who were to be committed to such institutions. On the other hand, these institutions were also affected by local policies about admission and discharge developed and implemented by the Managing Committees of the various institutions themselves. They also need to address the inter-relationship of political and professional factors. This is especially the case at national level, for example, in relation to the Mental Deficiency Act of 1913 and its category of ‘moral defective’ which brought into the asylums women who had given birth to an illegitimate child while receiving poor relief. In that example, an extension was occurring in the social construction of mental deficiency. But increasingly political decisions about how the socially incompetent could be segregated into institutions came to depend upon professional practice and expertise: compulsory education, age-related pedagogic expectations and increasingly sophisticated methods of testing intellectual ability, with the schoolroom as a laboratory, became the means for differentiating among the population. It was issues such as these that the Defective and Epileptic Children Committee of the Education Department highlighted in its 1898 Report:

From the normal child down to the lowest idiot there are degrees of deficiency of mental power; and it is only a difference of degree which distinguishes the feeble minded children from the backward children who are found in every school … and from the children who are too deficient to receive proper benefit from any teaching which the School Authorities can give … Though the difference of mental power is one of degree only, the difference of treatment is such as to make these children … a distinct class.9

The paradigm for understanding change in the voluntary asylums in the years with which this chapter is concerned is thus a complex intermingling between a variety of arenas: national and local, political and professional.

II

The creation of the five voluntary institutions for idiots occurred between the end of the 1840s and the late 1860s. The Western Counties Asylum at Starcross near Exeter was opened in 1864, the same year as the Northern Counties Asylum (subsequently the Royal Albert Institution) at Lancaster. In 1868 the Midland Counties Asylum at Knowle in Staffordshire began in a temporary building and, though six years later it moved to a 12-acre site, its financial difficulties were by no means at an end.

Each of these institutions was based on the initial model created by the Charity for the Asylum for Idiots established in 1847 by the Rev. Dr Andrew Reed, a Nonconformist minister and established charity organiser. Its initial property, Park House at Highgate in London, was soon full and the charity accepted the offer of a lease on Essex Hall, Colchester from Samuel Morton Peto, the wealthy railway magnate, which was used as a branch asylum of the London Charity until 1858. In 1859 Essex Hall became independently established as the Eastern Counties Idiot Asylum electing patients from the counties of Essex, Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. Meanwhile, in the earlier 1850s the Charity for the Asylum for Idiots had acquired a much larger site at Earlswood Common near Redhill in Surrey with space sufficient for a large asylum for 500 patients. Even though the buildings were not complete, it began to move patients there in 1855 from Park House and Essex Hall despite financial insecurity and a potentially damaging confrontation with the Commissioners in Lunacy. The award of its Royal Charter in 1863, however, marked the beginning of a significant period in Earlswood’s history:

Within the next ten years the asylum would expand both its patient numbers and subscribers, revamp its administrative system, create a comprehensive system of case books and admission records and, through its new medical superintendent, receive prominence as a medical institution of some repute.10

Not all the institutions founded in its image would be able to claim so much so quickly. The Eastern, Western and Midland Counties operated on a much smaller scale in relation to patient numbers than Earlswood or Lancaster; and financial vulnerability and uncertainty were to be a recurrent experience at the Western and Midland Counties until much later in the century.

What each of these institutions had in common, however, was a commitment to the training of those who, in the language of the time, were defined as educable idiots. The prominence accorded to the twentieth-century ‘warehouse’ model11 of institutional care means that it is difficult now to recapture the sense of positive optimism that pervaded the origins of the voluntary asylums in mid-nineteenth-century England. The Western Counties Asylum, for example, had as its principal object to provide opportunities for those ‘likely by careful treatment to be capable of mental improvement’.12 ‘Buildings that now fill us with despair were seen as model environments full of promise’13 in which could occur the creation of economically independent and morally competent individuals by a combination of moral training and task-centred learning in an environment that emphasised health, nutrition, exercise and the creation of habits of discipline.

The notion that ‘the idiot may be educated’14 owed much to the pioneering work of Itard and his pupil Seguing, in relation to the Wild Boy of Aveyron and the publicity that attended it. The latter’s work at the Bicêtre in Paris seeking to prove that idiots were trainable by a combination of experience and association led to the publication in 1846 of Traitement Moral, Hygiène et Education des Idiots which ‘soon secured him an international reputation’15 and which was translated into English in 1855. Meanwhile, almost simultaneously the work with cretins of Dr Guggenbühl, who had himself been influenced by the work of Itard, ‘became more readily available in English following William Twining’s visit to his establishment … near Interlaken which led to the publication of his Some Account of Cretinism and Institution for its Cure (1843)’.16 Periodicals such as the Edinburgh Journal and the Westminster Review also contributed to the dissemination of information about these schemes by articles published later in the 1840s.17

Since, ‘tis not decreed the idiot born, Must a poor idiot die’,18 the voluntary institutions were established within a climate of optimistic expectations of improvement. That optimism and the benefits which the institutions thought they could provide:

are not limited to the advantages which result to the idiots themselves, but they extend in large measure to the poverty stricken homes of their parents, to the relief of many a respectable hardworking family and even to the neighbourhood where the poor lad used to wander a forlorn outcast of society.19

If the institutions lifted the burdens of financial vulnerability and constant care from families, they were also concerned to emphasise the benefits accruing to individual inmates themselves. Often this took the form of comparisons of the inmates’ behaviour before and after admission published, for example, in Annual Reports or used in fund-raising speeches. Frequently before admission, the medical officer at the Western Counties Asylum pointed out in one such address, the children ‘have not been well fed, clothed or cared for’. Once in the Asylum ‘they are well clothed, well, judiciously and regularly fed and exercised … (and) from the affection and kindness shewn to them, they are at once much happier’. For the idiot of the lowest class – ‘speechless, inexpressibly filthy in his habits, unfit to sit at meals with his family, cramming the food into mouth with his hands, nay choking himself and vomiting it back on his plate’ – the institution’s training regime held out the prospect of teaching

him to walk, to eat his food decently with a knife and fork, to leave off his filthy habits, to dress and undress himself instead of tearing his clothes to pieces, perhaps to articulate a few words … make him fit to be kept in the same room with the rest of his family

while for its higher grades reading, writing, acquiring the skills of certain trades and attending in an orderly manner the services of the church were all indicators of improvement.20

Sometimes particular instances of individual improvement were cited to illustrate what the Asylum had achieved:

O.P. a boy of twelve when admitted was very backward in all branches of learning and could not use a pencil … by careful and continuous training … he is now able to write fairly in a copy book and to do sums of long division.

L.F. This girl came to us from a home for feeble minded girls and could neither read nor write. She can now read easy tales and write so well that her friends are delighted with the letters she sends home to them. She has moreover become quite a good housemaid.21

Less frequently, letters from former inmates were published extolling the benefits they had received, as in the case of this example, printed as it was received:

I am trying to be a good girl I often think and talk to mother of what you are doing at Starcross … thank you for all you have done for me whilst I was with you. Mother says it done me good.22

Such stories of individual improvement played an important part in the publicity for institutions, especially for those dependent on subscription income. In the competition for their initial income and continued support, subscribers needed to be constantly reminded that their money was achieving results.

But if such opportunities for improvement existed, they were available to only a small section of the population who might potentially benefit from them. In 1881, for example, only some 3 per cent of the estimated 29,542 idiot inmates of institutions were in special idiot asylums. ‘The remainder were still inter-mingled with criminals, lunatics, indigents and others in workhouses, lunatic asylums and prisons.’23 But Gelband’s research has suggested that the number of mentally retarded paupers outside institutions nearly equalled the number of those of that category who were in institutions of all kinds.24 Progressively, however, during the 1860s the Poor Law Board had sought to abolish outdoor relief where it could, including the small allowances often paid to families looking after a mentally deficient person. At the same time the Commissioners in Lunacy increasingly advocated separate provision for pauper idiots either within, or completely distinct from, the Poor Law workhouse or the county lunatic asylum. In this context the voluntary institutions occupied a small but significant niche. For a considerable section of the population private madhouses were too expensive while the Poor Law workhouses were socially unacceptable.25 For them the voluntary institutions represented an alternative to the only other available source of help: that of care provided by family or kin.

If individual improvement represented the goal of the voluntary institutions, philanthropic endeavour was to be the means by which it would be attained. In that respect, too, the response to those with the condition of mental deficiency was part of the broader fabric of Victorian society. Notwithstanding the growth of government in social affairs and the development of mutual aid and self-help organisations, philanthropy played a major role in the supply of welfare in Victorian England. ‘So many good causes were catered for – stray dogs, stray children, fallen women and drunken men.’26 If there was no subject which could not arouse the philanthropic urge of the Victorian public, the practice of mental improvement for children would appear to have much to commend it to potential supporters. In fact, as I showed earlier, the financial experience of the various voluntary asylums of nineteenth-century England was by no means comprehensively successful.

What the institutions had in common was a system, already well established in the voluntary hospitals, whereby subscribers were entitled to vote for the election of inmates. It was only the Western Counties which significantly deviated from this practice as it increasingly drew the majority of its inmates from among those publicly funded by the Poor Law Boards of Guardians. At its inception, however, the Western Counties, in common with the other voluntary idiot asylums, looked to subscriptions and donations as its principal source of funding.

The various benefits associated with the philanthropic gift have been discussed in a number of studies.27 On the one hand it gave subscribers the opportunity of social fraternisation with the aristocratic (and, in some cases, royal) patrons at the frequent social functions which took place both to raise additional funds and to publicise the work of the charity. On the other, in the case of the idiot asylums and the voluntary hospitals on which they were closely modelled, it gave subscribers an entitlement to vote in the election of potential patients or inmates. At Earlswood, for example, in return for the minimum subscription of one half guinea, an individual received the right to vote in the year’s two elections of inmates held in April and October, attend its social events and vote on policy at the Annual General Meeting. A life vote was given to each individual who subscribed five guineas which entitled subscribers to one vote at every election until their death. Both general and life votes increased pro rata. This meant that wealthier subscribers had more ‘political clout’ and potentially disproportionate influence in the competition for inmate selection.28

There was general agreement among the superintendents and medical staff of the idiot asylums that children should be admitted at an early age; and the original intention was that they should usually remain for a maximum period of five years and not beyond the age of 15. ‘It cannot be too strongly impressed upon persons interested in the education of the feeble minded,’ the Superintendent of the Western Counties affirmed, that:

experience proves childhood and youth to be the best time for developing any latent faculties they may possess … Better results are obtained when the pupils are between the ages of six and fifteen than at any subsequent period of their lives.29

But by the end of the nineteenth century that aspiration was already beginning to be in contrast to the practical reality of the Asylum. In 1898, for example, only a minority (125) of the inmate population (282) at the Western Counties were aged between 5 and 15; the remainder were all older, 64 being aged 20 and upwards.30 Several factors may, separately or in combination, explain this change: the declining employment opportunities outside the Institution; the need of the Asylum itself to retain trained workers to produce goods themselves and transmit their skills to those who were younger; the shifting discourse on mental deficiency that occurred in late Victorian England. The consequences, however, are less contentious: even before the 1913 Mental Deficiency Act the tendency towards larger-scale, longer-stay institutions with a more adult population was already occurring. In that context it becomes all too easy to attribute their failure to return their inmates to a life outside the institution ‘to the hopeless nature of the idiots themselves as well as to the allegedly unrealistic ideas that their educators had about improvement’.31

By the beginning of the twentieth century the world of the voluntary asylums looked set for substantial change. There was considerably less emphasis – politically and professionally – on improvement and an increasing discourse on containment which structured the form of the 1913 legislation. Equally, not only in relation to the voluntary institutions for mental defectives but more generally in the debate about social and individual welfare, the boundaries between state activity and philanthropic endeavour were being significantly re-negotiated. And within the institutions themselves, size and scale meant an increasingly segregated and differentiated environment which reinforced the geographical separation of the large purpose-built asylums in their pleasure grounds and agricultural pasturage that had occurred in the second half of the nineteenth century. ‘Collecting idiots together as a means of alleviating their solitude and isolation was (evolving) into the mass organisation of their daily life and the denial of their individuality.’32

The origins of the Western Counties Idiot Asylum lie in a public meeting held at the Castle in Exeter in November 1862 at which it was decided that ‘it is desirable to establish an Institution for those idiot children of the poor who shall appear to be likely by careful treatment to be capable of mental improvement’.33 The first admissions took place exactly two years later in November 1864. Since its sole object was the training of children, the Commissioners in Lunacy decided that it should be exempt from the strict operation of the Lunacy laws, and in March 1865 it was certified by the Poor Law Board as a school to which Boards of Guardians might send their children. Exemption from the Lunacy laws meant that the Institution avoided the annual expense of applying for a licence and the requirement of a resident medical practitioner. The Commissioners in Lunacy did, however, pay occasional visits of inspection. As the Institution became more settled and established, its Management Committee successfully applied in 1875 to the Devon Quarter Sessions and was licensed as an establishment for the reception of idiots. The licence allowed the Institution to accommodate forty inmates and ended the age restriction which had originally been only for children between the ages of 6 and 15.

In 1887 the Institution sought registration under the 1886 Idiots Act for 180 cases. Five years later its official designation, as recorded in the Commissioners in Lunacy returns, changed from being one of the provincial licensed houses devoted entirely to the reception of idiots to that of an ‘idiot institution’. By that time there were 200 inmates resident in the Asylum. But, unlike several of the other establishments, there was still no requirement of a resident medical practitioner. The first such appointment was not made until 1937. He became Superintendent in 1945 when the long family tradition of the successors of William Locke, appointed Superintendent seventy years before, came to an end.

Another family with a long-standing influence on the affairs of the Institution was the Courtneys, the Earls of Devon. William Reginald Courtney, eleventh Earl of Devon, chaired both the initial public meeting in 1862 and the provisional committee of Devon nobility and gentry which was established to formalise plans for the Institution. In the process he began a continuing association between the Asylum and the Courtney family which lasted for a long period of its history, even after the Institution became part of the National Health Service in 1948. Successive Earls of Devon served as Presidents of the Institution in unbroken sequence between 1864 and 1935: and, with the exception of the years between 1908 and 1920, members of the Courtney family were also Chairmen of the Managing or General Committee. It was the eleventh Earl of Devon who leased a house and two acres of land adjacent to his own estate at Powderham near Exeter to the fledgling Institution, corresponded with the Commissioners in Lunacy about its legal status, prepared its draft constitution and played an active role in the recruitment of its initial staff. That same Earl of Devon also played a part on the national stage in matters of mental deficiency, as a member of the Charity Organisation Society’s ‘committee for considering the best means of making a satisfactory provision for Idiots, Imbeciles and Harmless Lunatics’. With its call for a greater recognition of the difference between lunatics and idiots it was one of the influences behind the legislative distinction introduced by the Idiots Act of 1886. Its attempt at clarification, however, was short-lived. The 1890 Lunacy Act ‘completely overlooked this distinction, continuing to treat the terms “idiot” and “lunatic” as synonymous’.34

In common with many other nineteenth-century residential establishments, the management of the Western Counties Institution was vested in the General or Managing Committee and its House Committee. In addition, specialist sub-committees concerned with buildings and finance were also established. At its monthly meetings, the Managing Committee had general oversight of matters relating to the Institution. These included arrangements for the admission of inmates, appointment of staff, conditions of employment, receiving accounts, stimulating interest in the work of the institution in the Western Counties and contact with statutory bodies such as Boards of Guardians, the Local Government Board and the Commissioners in Lunacy. The remit of the House Committee, which met weekly at the Institution, was to superintend all the domestic arrangements, to inspect the whole establishment and to receive written reports. Initially these were supplied by the Matron – subsequently by the Superintendent – as well as by the Honorary Medical Officer.35

Membership of the General Committee was determined by election at the Institution’s Annual General Meeting, while the House Committee was chosen from among the members of the General Committee. Both, however, were exclusively male in membership. It was not until the appointment of local authority representatives in the 1920s that women became members of any of the Institution’s Committees. While women played no direct role in the management of the Asylum before the First World War, they were involved in its work in ‘separate spheres’. Female relatives of the Earl of Devon opened bazaars and helped with other fund-raising activities, while other female supporters provided extra ‘treats’ for patients including outings, books, magazines and games, and presents at Christmas. Women, of course, were also among those who provided financial support to the Institution by means of their own individual subscriptions and donations. This was of no small importance: for financial viability was one of the major issues in the management of the Institution for at least the first thirty years of its existence.

At its inception there appears little doubt that the officers of the Western Counties Asylum expected that its funds would come mainly from subscriptions and donations, both of which would offer an entitlement to vote for the election of inmates. The first list of subscribers and donors, printed in the 1869 Annual Report, indicated a total of 367, drawn overwhelmingly from Devon.36 The 1904 Annual Report listed 219 subscribers and donors who contributed less than 2 per cent of the Asylum’s income.37 Thirty years before, in 1874 almost 30 per cent of the Asylum’s income had come from that source. That in itself was a proportion much below what the officers of the Asylum expected. Successive Annual Reports drew attention to the problem. In its first Report the Committee made ‘an earnest appeal for increased support’.38 Two years later only forty-one new subscribers had been added with a total level of subscription of £44 9s Od, while the contributions of nine subscribers totalling £20 had been lost to the Asylum through death.39 Establishing local committees in many centres of the Western Counties to provide information about mental deficiency and to raise money for the Asylum met with only limited success. While thirty local secretaries were listed in 1876,40 ten years later there appeared to be only three local committees in Plymouth, Truro and for the county of Dorset.41 Writing against the background of a deficit of £350 in 1880, the Committee lamented that ‘they can only attribute the want of support to the fact that the Asylum, its objects and its aims are not sufficiently known and understood’.42 By the 1890s the explanation for low subscription income was ‘the growing feeling among the public that institutions of this sort should be supported by the State’.43 This experience was by no means unique to the Western Counties Asylum. In 1875 the Commissioners in Lunacy regretted that ‘sufficient funds have not been obtained in this wealthy district’ to aid the construction of an adequate building for the Midland Counties Asylum at Knowle near Birmingham;44 while David Wright has pointed out that at the more financially successful Earlswood Asylum the level of subscription income depended significantly on the wider economic circumstances of the nation in general.45

Income, however, was only one side of the equation. Expenditure was the other element that contributed to financial volatility. Initially at the Western Counties food and salaries consumed a significant proportion of the budget. Interestingly, though the number of attendants and other staff increased as the patient population grew in size, the proportion of total expenditure spent on salaries varied very little, from 27 per cent in 1874 to 28 per cent in 1904 (within a range of from 21 per cent to 31 per cent between the same dates).46 In 1883 when the patient population had increased by thirteen over the previous year there was no increase in staff, with the Committee anxiously considering ways of reducing its debt on buildings and the recurrent deficit on general expenditure. That represented an exceptional attempt to contain costs, though the Asylum officers were always concerned to emphasise its economic and efficient management especially in relation to average costs per inmate at other voluntary and public institutions.

Writing more generally of the voluntary system of residential care for children in the nineteenth century, Roy Parker points out that while land and buildings were often freely or cheaply available from wealthy patrons (such as the Earl of Devon at the Western Counties) ‘homes were expensive to establish and to keep open; charitable donations were rarely sufficient or sufficiently reliable’.47 Maintaining the buildings in a good state of repair, upgrading them to provide additional facilities and fulfilling requirements such as those ensuring safe exit in case of fire, became increasingly important at the Western Counties once the Asylum had been licensed in 1875 and all aspects of its provision became subject to the scrutiny of visits by the Commissioners in Lunacy. In the case of new buildings the cost was met by special appeals designated specifically for the Building Fund and by events such as the Elizabethan Fancy Fayre, a three-day event held in Exeter in 1882, and a Grand Bazaar under the patronage of the Prince and Princess of Wales. But significant as were such fund-raising events, they were insufficient by themselves to meet the costs involved and borrowing to build became a pattern of the Asylum’s financial management.

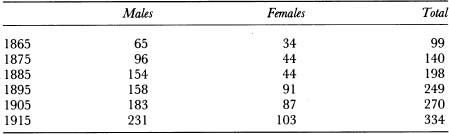

Building was a response to the growth in size of the Institution (and partly a cause of it) as well as a reflection of its growing diversification. Table 7.1 shows the pattern of growth in the inmate population at the Western Counties over its first fifty years. The particularly large increase between 1885 and 1895 is mainly explained by the completion in the late 1880s of accommodation for seventy-five extra children. Expressing its pleasure that such an expansion had been undertaken at this ‘very useful Asylum’, the Commissioners in Lunacy pointedly drew attention to ‘the great need throughout the country for institutions of this character’.48 Size seems also to have been a criterion in its change of status from a provincial licensed house to an institution for idiots in the early 1890s.

Table 7.1 Growth of the inmate population at the Western Counties Idiot Asylum (1865–1915)

Source: Commissioners in Lunacy Reports’, Western Counties Idiot Asylum Annual Reports

But its growth, both in absolute and relative terms, had been much slower than that at either Earlswood or the Royal Albert. Built originally for 400 occupants, the asylum at Earlswood became full in 1866 and, after it had expanded its potential size to 600 residents, reached full capacity again in 1878.49 The growth of the patient population at the Royal Albert was also significantly greater than at the Western Counties. Though they were founded in the same year, by 1874 at Lancaster there were already 196 inmates, with a range of buildings including schoolrooms, workshops, sick rooms, laundry and dormitories already in operation.50 Different financial experiences would mainly seem to account for the differences between them. At its foundation the Royal Albert was already much more financially secure than its counterpart in Devon. But especially in the twenty years after its formal licensing in 1875 the Western Counties significantly increased in scale and size.

Its commitment to expansion was at least in part an attempt to provide accommodation for those considered eligible who were waiting for admission. During its first forty years 1,023 children had been admitted to the Western Counties Asylum. But, as its Committee of Management report recorded, these figures represented a very small proportion of the numbers who had applied for admission.51 Unmet demand was only one factor explaining expansion. It came to be more frequently argued by the Superintendent that increased numbers would facilitate a more rigorous classification of the patient population, both in relation to education and its developing programme of industrial training: ‘One great benefit attaches to an increase of numbers,’ he pointed out in 1877, ‘viz. that a better classification of the pupils’ training and teaching can be made.’52 Expansion too could bring the benefits associated with economy of scale.

That applied especially as the Institution began to move in the direction of increased self-sufficiency in relation to foodstuffs and other necessary items from the mid-1870s; and then, in turn, in a second phase towards the end of the nineteenth century, began commercially to sell the products of its expanding training workshops. In 1874 spending on food constituted over 40 per cent of the Asylum’s expenditure. The much broader but undifferentiated category of housekeeping and provisions had been reduced to 28 per cent in 1904.53 Half of the seven acres owned by the Asylum in 1888 were given over to the kitchen garden ‘which supplies all the fresh vegetables, potatoes and fruit required for the Asylum’.54 The acquisition of animals and poultry further consolidated its self-sufficiency and provided training in agricultural pursuits to some of its inmates. In the late 1890s the Commissioners in Lunacy endorsed the Managing Committee’s hope that extra land could be acquired especially to provide pasturage for additional cows. ‘A good supply of pure milk,’ they pointed out, ‘is essential in an establishment for idiots.’55

Once it was recognised that increased self-sufficiency and the sale of goods could bring the financial security which had eluded the Institution in its early years, the selection of suitable inmates became increasingly important. While the education and training of the improvable idiot had always been part of its raison d’être, they increasingly became more central to its economic strategy. This expressed itself in the Managing Committee and Superintendent’s opposition to degeneration into a ‘mere custodial establishment for helpless and unimprovable idiots’,56 on the one hand and, on the other, to a ‘judicious weeding out’57 of those unlikely to benefit either themselves or the Institution from the training that was offered.

Increasingly, in the later nineteenth century the Institution was able to select its prospective inmates from a geographically wider catchment area. In the years from its foundation to 1877, children from the Western Counties – of Cornwall, Devon and Somerset – accounted for the vast proportion of its inmate population, with children from its local catchment county of Devon accounting for just over two-thirds of the total. In 1914 Devon-born inmates still predominated in relation to those from the four Western Counties: but, by then, patients from South West England (including Dorset) were in a minority compared to those from elsewhere in the country. Of the total of 306 inmates only 103 (34 per cent) were from the Western Counties. This is a reflection of the extent to which the Institution had carved out a distinctive niche for itself not only in relation to the training which it provided (which was not dissimilar to that provided in the other idiot establishments) but also for the specific category of pauper idiots. In contrast to the other establishments with their mainly private, fee-paying inmates elected by subscribers, the Western Counties came increasingly to specialise in the education and training of pauper idiots. It was in fact only the Royal Albert Asylum with 219 pauper patients in 1904 which approached the 261 at the Western Counties at the same date.58 But as a proportion of the total inmate population its 35 per cent of pauper inmates paled into insignificance compared to the 96 per cent at the Western Counties.

Though the Superintendent was still lamenting in 1901 that ‘there are still many Boards of Guardians who endeavour to send us only their helpless and unimprovable cases’,59 the Asylum’s own policy of careful and rigorous selection, together with the swift discharge of those unsuited to its regime, transformed it from a purely local and regional institution into one with a national catchment area. In this way the Western Counties Asylum became increasingly dependent on the revenues which flowed in from Boards of Guardians all over the country, in contrast to the static and then declining proportion of subscription and donation income from its more regionally based local supporters. If such a solution had been part of an organised quest for greater financial stability, it had served both to differentiate the Western Counties from other idiot establishments and to fulfil its original purpose as an institution for the idiot children of the poor.

IV

The decision about which prospective candidates should be admitted to the Institution was taken by the General or Managing Committee. The constitution and rules agreed when the Western Counties Asylum was established and confirmed by the Poor Law Board had set the broad parameters. These related to age, likelihood of improvement and financial guarantees. No child was to be admitted before the age of 6 or after they had reached 15, with an expectation that the usual length of stay would be five years. Though there remained a commitment to an early age of admission, by the end of the nineteenth century, as I pointed out above, the upper age limit had been significantly breached.

The child’s potential for improvement was another important feature of selection for admission. Children who were blind, deaf or suffered from epilepsy were usually automatically excluded from further consideration. While for the remainder, no case was to be approved ‘unless there be a reasonable expectation … that it will derive benefit from the treatment to be adopted in the Institution’.60 Those who slipped through this net and entered the Asylum, but who showed no sign of improvement there, were discharged back to their families or to the Poor Law workhouse. Financial guarantees were also sought prior to admission. Written arrangements were entered into with Boards of Guardians or parents and friends for the maintenance and support of the children while in the Asylum and the defrayment of all expenses concerned with their removal or burial.

From its earliest years the Management Committee relied heavily on the assessment provided by George Pycroft, a local medical practitioner and long-serving honorary Medical Officer to the Institution. His view was especially important in guiding the Committee to consider the likelihood of improvement. It was based upon his own examination, usually conducted in the Asylum, letters from family and friends and established figures (such as clergymen) in the local communities from which the applicants came. In addition, he had available the answers to specific questions on the application form for admission. In the early 1880s Pycroft described the details of his initial assessment:

I look him all over, test his mind and the state of his bodily health. I enter his description in a book which is called the Case Book … I put down whether he can speak, count, read, write, walk, dress himself, feed himself, whether he has the use of his hands, is mischievous, what his temper is, what the cause of his idiocy is and so forth.61

At the same date, Pycroft also had available the details from the Application Form which asked both about the child’s mental condition, sensory abilities and general health as well as the circumstances of the family, the health and intelligence of any other children and whether there was any history of insanity, idiocy or epilepsy in the family.

Pycroft himself became an important advocate for the Asylum. His address to its 1882 Annual General Meeting showed him to be well acquainted with the alternative theories about the causes of idiocy and moving towards an elementary classification in his distinction between low ‘little better than an animal’; not quite so low ‘where the child can speak a little or make signs’; while those of a higher grade ‘can converse tolerably and understand what is said’ but have all ‘the passions of an ordinary man without the mind of a man to control them’.62 While he counselled his hearers against unrealistic expectations of what institutions could achieve by way of complete independence, he saw their value in the relief which they offered to parents. An Order of Admission offered them, he suggested, ‘joy of happiness, hope of improvement, hope that at last he may possibly be raised out of the gloom of his mental darkness … a response in place of a blank, vacant stare’.63

For most of its first fifty years the Western Counties Asylum had more boys in residence than girls. In 1877 there were 34 boys and 19 girls; in 1912, 210 and 94 respectively.64 There can be little doubt that this distinction by gender was the result of cultural assumptions held by those in charge of selecting from potential applicants, whose numbers always exceeded the available accommodation. While the 1881 Census indicated ‘no great disparity between the number of males and females described as Idiots and Imbeciles’, the national figures of those admitted to all the voluntary idiot establishments between 1875 and 1884 showed that only one third were female.65 William Locke, the Superintendent of the Western Counties Asylum, found the preponderance of boys in institutions not at all surprising:

Weak minded girls with a certain amount of intelligence are more amenable to treatment at home, and in some instances may even be helpful to their mother in small things, while boys soon get beyond maternal control and, being allowed more freedom out of doors, too often become troublesome to their neighbours and the public and their seclusion is then called for.66

Seclusion, however, was in a rigorously segregated environment. Supervised meals, church services and organised entertainments were the only occasions on which the sexes were together. Classes, workshops and recreation areas were either for boys or girls and their dormitory accommodation was in separate wings of the large main house, with the accommodation for the Superintendent and his family in between.

Those admitted to the Western Counties Asylum in its early years became part of a training regime which emphasised the three Rs, and lessons in colour and form, singing, speaking, dressing and time, with drill as the means of inculcating habits of discipline and orderliness. In the subsequent phase, in the final quarter of the nineteenth century, the child entered into an Institution which was structured around the acquisition of basic educational skills in the morning and occupational training in the workshops during the afternoon. Once an appropriately qualified schoolmaster and schoolmistress had been appointed in the late 1890s, they took over the preliminary educational assessment which formerly had been undertaken by the Superintendent. In the early years of this century boys were assigned to one of six classes on the basis of age and ability, girls to one of five. In the upper classes the three Rs were taught; in the lower, object lessons were used to awaken an interest and curiosity. Walks and excursions to coast and country were part of the educational programme. So too was character learning. Writing of the teaching staff, the Superintendent pointed out, ‘By their precept and example they help to form the tone and character of the more intelligent pupils, whose example, in turn beneficially affects the children of a lower grade.’67

Successive reports during the 1890s suggest that as a result of its conscientious commitment to a selective admissions procedure and the education provided in the Institution, a rising proportion of its inmates were by no means ineducable. Thus, of 181 inmates in 1890, 68 could speak well, 31 could read well, 52 could write fairly from dictation, with 36 able to do simple addition and 19 to work sums in either the first four or compound rules. Ten years later in 1900 from a total population of 250, 219 could speak well, 90 could read well, 143 write fairly from dictation, 66 could do simple addition with 80 able to work sums in either the first four or compound rules. By contrast the numbers at the other end of the ability range had significantly decreased over the same decade. Forty-four of the 181 were dumb in 1890 compared to 4 out of 250 in 1900; likewise, 66 knew no letters or words in 1890 compared to only 14 in 1900; 48 could do nothing but scribble in 1890, a figure reduced to 17 in 1900; while 58 could not count at all in 1890, only 8 were unable to do so by 1900. By the same date only 20 were unable to attend service in chapel and 74 were able to recite alone.68

But it was its developing programme of industrial training which came increasingly to characterise the regime for the inmates of the institution. The development of an industrial training regime owes much to the appointment of William Locke as Superintendent in 1874 and the licensing of the Institution the following year. It was enthusiastically carried on by his son and successor, Ernest Locke, and by the latter’s brother-in-law and sister who continued that family’s association with the Institution until succeeded by its first Medical Superintendent in 1945. Before William Locke’s appointment, girl inmates assisted the housemaids in making beds and sweeping, boys cleaned knives and shoes, tended the gardens and helped with other outdoor work. In one of its early reports the Committee pointed out that ‘very little can be done in the way of education or industrial training’.69 Locke’s appointment brought about change. Initially the limited range of trades were supplied for the institution itself. Thus the children’s boots and uniforms and all the window sash cord for its new buildings were made in the Asylum’s workshops. But increasingly, as the number of trades increased and diversified, commercial sales began to develop which, in time, contributed to the Asylum’s improved and more stable financial position.

By the end of the 1880s boys especially were engaged in a more comprehensive set of occupations: shoemaking, tailoring, sash-cord-making, in addition to gardening, laundry and domestic work and basket-making. At that date the occupation of girls was still severely restricted to sweeping, dusting, bed-making, sewing and knitting and laundry work. By 1904, however, there had been a considerable expansion in the occupations available to both boys and girls. Mat- and brush-making together with carpentry, wood-carving and fretwork as well as work in the bakery had been added for boys; while girls’ occupations by that date included dress-making, Honiton lace-making, straw hat-making and embroidery. Much of the occupational training was on an alternate week system which provided a variety of experience for the large proportion of the Asylum’s population who participated in such activities. In 1897 only 21 out of 247 residents undertook no work.70

Such work not only made the Institution more self-sufficient. The sale of products made in its workshops increasingly added to the Asylum’s income. The sale of work brought in £44 5s 11d in the year ended 31 December 1895, by 1904 £234 8s 5d and by 1914 £632 4s 7d.71 Almost as important was the publicity which the products – such as embroidery and Honiton lace-making – gained for the Institution. No opportunity was missed to exhibit such work in local craft and agricultural shows and to take part in the exhibition of the goods produced by the inmates of all the voluntary institutions such as that held at the Royal Albert in Lancaster in 1897 to mark the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria.

Recreation constituted the third element of the inmate day. Here, too, the trend was one of expansion. In 1880 there was music and dancing on two evenings each week, while swings and gymnastic apparatus were available in the playground. Winter evenings created an especial problem for the attendants. A variety of indoor games – billiards, draughts, bagatelle, dominoes and house building with bricks – were popular amusements. Many of them were donated by friends of the Institution along with toys, scrapbooks and a rocking horse. Dissolving view entertainments, magic lantern shows, visits by conjurers, pantomime performers and a Welsh male voice choir also helped to pass the winter evenings. At other times athletic games – cricket, football, running and jumping – and drill occurred either outdoors or in the Recreation Hall which was gifted in the early 1880s. Educational visits have already been mentioned, but there were also outings for picnics on the nearby Dawlish Warren, to Powderham Rectory, where one of the Courtney family gave an annual picnic, and, in winter, to the pantomime in Exeter.

Annual events marked the passing of the individual and collective year. Birthdays were celebrated with special tea parties, while Christmas came to be an especially important event. The Recreation Hall ‘decorated with flags and evergreens and lighted by 150 electric lamps’72 was the scene for an annual entertainment provided by the inmates to which the public were invited. Musical drill, action songs by pupils in costume and sometimes a pantomime performance preceded the distribution of presents and toys which had been given by friends of the Institution.

As in its financial affairs, so too the Asylum became increasingly self-reliant in recreation. By the outbreak of the First World War, a Fife and Drum Band had been established as well as a brass band taught by the schoolmaster and one or two members of the staff band; a Rifle Club was also in operation for male attendants. By the same date a separate sitting room had been created where those older inmates who acted as monitors or foremen in the workshops could sit and read, write letters or play draughts.

Events of national importance generated a particular enthusiasm. The fiftieth anniversary of Queen Victoria’s accession was celebrated by a Jubilee Fête in the Asylum’s grounds; while the coronation of her grandson King George V in 1911 was marked by a day of special events to which the public were invited: a military spectacle resembling Trooping the Colour was held in the morning, organised sports in the afternoon, while in the evening, against the illuminated buildings of the Asylum, a Flag Drill took place accompanied by the Boys Band.

The consequence of this diversification in the Institution’s activities was an increase in the number of its buildings. As the Institution sought to house more inmates, extend its facilities and comply with the standards laid down by the Commissioners in Lunacy, its regular routine was frequently interrupted by building work in progress on its expanding site. On more than one occasion the Committee acknowledged the extra strain placed upon its staff of attendants as the adaptation of existing premises as well as new building work prevented outside recreation and confined the children to their schoolrooms and dormitories.73

Such a pattern was by no means limited to the Western Counties Asylum. In one of its annual reports the Commissioners in Lunacy referred to recent developments at Earlswood which included the construction of extensive farm buildings, the roofing of the gymnasium and additional staircases to aid escape in case of fire. At the same time it noted that a considerable sum of money was already in hand for building a detached hospital.74

If building work was one sign of the developing Institution, another sign of change was the pressure to alter its title. Keen to do away with the ‘obnoxious terms of “Asylum” and “Idiot” ‘, at the beginning of the twentieth century the Superintendent proposed a change of considerable significance: the development by the recently created County Councils of Homes for Helpless and Unimprovable Idiots, but sought for his own Institution a title such as the Western Counties Training Institution for the Feeble-minded to delineate its distinctive character.75 After some controversy ‘Idiot’ was deleted, but ‘Asylum’ remained in its title: though after 1903 the Superintendent and Committee of Management were allowed to amplify its objective as a Training Institution for the Feeble-minded.

V

Ernest Locke’s proposals concerned more than simply a change of designation. They were an attempt to respond to broader changes that were taking place in relation to mental deficiency. These broader changes can be considered as the ‘reconceptualisation of mental deficiency as a social rather than a private problem’.76 One facet of this reconceptualisation was the supply of special education. By 1903 special schools had been established in London and fifty other authorities.77 The origin of such provision in the public sector lay with the establishment in 1880 by the Metropolitan Asylums Board of a school with accommodation for 1,000 pupils at Darenth in Kent. In the event, pressure on space for adults, since its other asylums at Leavesden (Herts.) and Caterham (Surrey) were already full, meant that by 1890 ‘the fruit of the first attempt by a statutory body to develop the potentialities of subnormal children’ housed only 300 boys and 168 girls.78 The 1890s, however, were a decade which experienced the beginnings of a serious attempt by local School Boards to establish special provision for those who were judged incapable or unsuitable for receiving education in a ‘normal’ school.

Initially this principally applied to children whose blindness or deafness prevented them from benefiting from such an environment. But in the ‘laboratory’ presented by the school classroom, ‘there were also found to be children who, while apparently fully provided with their complement of senses, appeared unable to learn the lessons of the school’.79 It was this group who became the focus of the Defective and Epileptic Children Committee of the Education Department, and its proposals embodied in legislation in 1899 gave local authorities permissive powers to create special schools and classes for those who were ‘by means of mental defect incapable of receiving proper benefit from the instruction in ordinary schools’.80 This legislation became compulsory in 1914 but not until after much controversial discussion had taken place in central government concerning the respective interests of the Board of Education and the Home Office.81

Such legislation and the growing responsibility of statutory authorities in the education of mentally deficient children posed a significant challenge to institutions like the Western Counties Asylum just at the time when its internal regime was beginning to produce a degree of financial stability in its affairs. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that Locke proposed an alternative scenario which looked to the statutory authorities to make provision for the helpless idiot while proposing that institutions ‘outside the state’ such as his own should continue to offer education and training to those it deemed capable of benefiting from its regime.

If the voluntary asylum, on the one hand, was increasingly having to come to terms with the implications of universal schooling, on the other was the challenge presented by the changing discourse on mental deficiency. ‘Edwardian doctors, psychologists, social workers and social theorists differed widely about the precise causes and symptoms of feeble-mindedness; but … they were virtually unanimous in their belief that the condition was largely incurable.’82 This was in sharp contrast to the optimism that had attended the foundation of the voluntary asylums in the mid-nineteenth century and the regimes of education and training which they had established. But it reflected the growing prominence of eugenic ideas in the discussion both of mental deficiency and national efficiency in which the idiot came to be perceived less as ‘a challenge for scientific and philanthropic pedagogy than as a burden on the nation’.83

In the later nineteenth century the public debate on mental deficiency shifted, especially in its gender focus, away ‘from the prisons and the habitually criminal imbecile to the workhouses and their transient weak-minded inmates, feeble-minded women in particular’.84 Whereas the former suggested a discourse predominantly structured around men, the ‘faces of degeneration’ in the early twentieth-century debate were inescapably female. Not only were mentally deficient women ‘seen as the biological source of mental deficiency, they also posed a deep threat to existing middle-class and respectable working-class notions of sexuality and familial morality’. It is this, it has been suggested, which accounts for ‘the near hysteria which characterises discussions about the social problem of mentally deficient women’.85 It also explains the outcome both of the Royal Commission on the Feeble Minded and the 1913 Mental Deficiency Act in the shift towards compulsory segregation and a more custodial system.

The implications of such a shift were clear for institutions like the Western Counties Asylum. Not only were they in danger of losing the educable idiot child to special schools, they would also be less able to select among a more adult population. This too explains Locke’s advocacy of different client groups within the general category of the mentally deficient for the statutory sector and the voluntary establishments. It was a defence against change: the compulsory containment of undifferentiated degenerates, as the early twentieth-century debate constructed them, had no place in the regime of his Institution.

This was the background to the emotional outburst by Major Nevil Thomas, Chairman of the Western Counties Management Committee, at its Annual General Meeting in 1914:

The Committee are most determined to keep this House full of the same class of patients we have always had … We spent a tremendous lot of money on rooms and appliances for teaching and are not going to have them wasted by having a lot of blithering idiots who cannot learn. We are going to take the very highest class of mental defectives and teach them to the best of our ability.86

Such sentiments represented an understandable determination on the part of the Western Counties Asylum to continue its hard-won achievements against the encroachment of change. But, in the event, it would be national policy, especially after the First World War, that would take the Institution into a very different environment from the final vestiges of its nineteenth-century inheritance which Major Thomas so emotionally defended.

1 The material in this chapter was collected as part of a longer historical study of the Western Counties Asylum (subsequently the Royal Western Counties Hospital) funded by the Northcott Devon Medical Foundation. I am grateful to the trustees for their support. For access to documents in their possession I wish to thank the Exeter Health Authority and Mr A. B. Rowland.

2 M. A. Crowther, The Workhouse System 1834–1929, London, 1981, p. 67.

3 R. A. Parker, ‘An Historical Background to Residential Care’, in I. Sinclair (ed.) Residential Care: The Research Reviewed, London, 1988, p. 14.

4 E. Goffman, Asylums, New York, 1961.

5 M. Foucault, Discipline and Punish, London, 1977.

6 A. Scull, Museums of Madness, London, 1979, p. 240.

7 L. J. Ray, ‘Models of Madness in Victorian Asylum Practice’, European Journal of Sociology, 1981, vol. 22, pp. 229–64; J. K. Walton, ‘Lunacy in the Industrial Revolution: A Study of Asylum Admissions in Lancashire 1848–50’, Journal of Social History, 1979, vol. 13, pp. 1–22; J. K. Walton, ‘Casting Out and Bringing Back in Victorian England: Pauper Lunatics, 1840–70’, in W. F. Bynum et al. (eds) Anatomy of Madness, vol. 2, London, 1985.

8 M. A. Barrett, ‘From Education to Segregation: An Inquiry into the Changing Character of Special Provision for the Retarded in England c. 1846–1918’, unpublished PhD thesis, University of Lancaster, 1987; H.S. Gelband, ‘Mental Retardation and Institutional Treatment in Nineteenth Century England’, unpublished PhD thesis, University of Maryland, 1979; D. Wright, ‘The National Asylum for Idiots, Earlswood, 1847–1886’, unpublished DPhil thesis, University of Oxford, 1993.

9 Cited in N. Rose, The Psychological Complex: Psychology, Politics and Society in England 1869–1939, London, 1985, p. 99.

10 Wright, ‘Earlswood’, p. 47.

11 E.J. Miller and G. V. Gwynne, A Life Apart, London, 1972.

12 Western Counties Asylum [W.C.A.] Constitution, 1864.

13 J. Ryan with F. Thomas, The Politics of Mental Handicap, London, 1980, p. 94.

14 Cited in K.Jones, A History of the Mental Health Services, London, 1972, p. 183.

15 J. S. Hurt, Outside the Mainstream: A History of Special Education, London, 1988, p. 110.

16 Ibid., p. 111.

17 Wright, ‘Earlswood’, p. 67.

18 E. Grove, A Beam for Mental Darkness: for the benefit of the Idiot and his Institution, London, 1856, p. 4.

19 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1883, p. 13.

20 G. Pycroft, An Address on Idiocy, Exeter, 1882, pp. 10–11.

21 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1901, p. 14.

22 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1902, p. 16.

23 Rose, Psychological Complex, p. 95.

24 Gelband, ‘Mental Retardation and Institutional Treatment’, p. 359.

25 Wright, ‘Earlswood’, p. 24.

26 D. Fraser, The Evolution of the British Welfare State, London, 1984, p. 124.

27 R. Porter, ‘The Gift Relation: Philanthropy and Provincial Hospitals in Eighteenth-Century England’, in L. Granshaw and R. Porter (eds) The Hospital in History, London, 1989; F. Prochaska, The Voluntary Impulse, London, 1988; ‘Philanthropy’, in F. M. L. Thompson (ed.) The Cambridge Social History of Britain 1750–1950, Cambridge, 1990.

28 Wright, ‘Earlswood’, pp. 115, 124.

29 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1899, p. 13.

30 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1898, p. 22.

31 Ryan with Thomas, The Politics of Mental Handicap, p. 102.

32 Ibid., p. 99.

33 Cited in J. Radford and A. Tipper, Starcross: Out of the Mainstream, Toronto, 1988, p. 27.

34 Jones, Mental Health Services, p. 185.

35 W.C.A. Minute Book, 25 November 1864.

36 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1869, pp. 18–28.

37 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1904, pp. 38–44.

38 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1865, p. 1.

39 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1867, p. 1.

40 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1876, p. 12.

41 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1886, p. 4.

42 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1880, p. 10.

43 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1893, p. 5.

44 ‘Annual Report of the Commissioners in Lunacy to the Lord Chancellor’, P.P. [1875], p. 49.

45 Wright, ‘Earlswood’, p. 122.

46 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1904, p. 5.

47 Parker, ‘An Historical Background’, p. 27.

48 ‘Annual Report of the Commissioners in Lunacy to the Lord Chancellor’, [1886], p. 65.

49 Wright, ‘Earlswood’, p. 76.

50 ‘Annual Report of the Commissioners in Lunacy to the Lord Chancellor’, [1875], p. 243.

51 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1904, p. 5.

52 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1877, p. 19.

53 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1874, p. 11; 1904, p. 37.

54 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1888, p. 6.

55 ‘Annual Report of the Commissioners in Lunacy to the Lord Chancellor’, [1897], p. 381.

56 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1905, p. 14.

57 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1898, p. 14.

58 Radford and Tipper, Starcross, p. 48.

59 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1901, p. 12.

60 W.C.A. Rules.

61 Pycroft, An Address on Idiocy, p. 10.

62 Ibid., p. 6.

63 Ibid., p. 15.

64 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1877, p. 20; 1912, p. 13.

65 ‘Annual Report of the Commissioners in Lunacy to the Lord Chancellor’, [1884–5], p. 21.

66 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1894, p. 4.

67 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1898, p. 15.

68 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1890, pp. 15–16; 1900, pp. 24–25.

69 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1869, p. 1.

70 W.C.A. Visitor’s Book, 19 March, 1897.

71 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1896, p. 18; 1905, p. 34; 1914, p. 36.

72 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1902, p. 33.

73 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1886, p. 8.

74 ‘Annual Report of the Commissioners in Lunacy to the Lord Chancellor’, [1875], p. 254.

75 W.C.A. Annual Report, 1901, pp. 12–13.

76 H. G. Simmons, ‘Explaining Social Policy: the English Mental Deficiency Act of 1913’, Journal of Social History, 1978, vol. 11, p. 389.

77 Rose, Psychological Complex, p. 103.

78 Hurt, Outside the Mainstream, p. 118.

79 Rose, Psychological Complex, p. 99.

80 Ibid., p. 103.

81 G. Sutherland, Ability, Merit and Measurement, Oxford, 1984.

82 J. Harris, Private Lives, Public Spirit, Oxford, 1993, p. 244.

83 Rose, Psychological Complex, p. 95.

84 J. Saunders, ‘Quarantining the Weak-minded: Psychiatric Definitions of Degeneracy and the Late Victorian Asylum’, in W. F. Bynum et al. (eds) The Anatomy of Madness, vol. 3, London, 1988, p. 291.

85 Simmons, ‘Mental Deficiency Act’, p. 394.

86 Radford and Tipper, Starcross, p. 52.