CHAPTER 7

Create Peaks and Avoid Valleys

No matter how hard you try to improve your organization’s customer experience, the reality is that your customers won’t remember much of it.

That’s because our brains aren’t wired like a video camera, recording every second of every experience. Rather, what we remember are a series of snapshots. And those snapshots aren’t taken at random. The camera shutter opens to capture the peaks and the valleys in the experience—the really high points and the really low points. Most everything else, all the parts of the experience that are just “meh,” fade into the background and disappear from our memory.

This insight about the inner workings of our memory was first explored in 1993 by the renowned behavioral psychologist Daniel Kahneman, who dubbed this the “peak-end rule.”1 Years later, management professors Richard Chase and Sriram Dasu built on Kahneman’s research and considered how the peak-end rule could be applied to service interactions.2 (Note that we’re going to focus on “peaks” in this chapter and “ends” in the next.)

Kahneman’s work led to a surprise conclusion: what we experience in the world can actually be quite different than what we remember about our experiences in the world. In our encounters with people and businesses, we might live through the minutia of an experience, but we won’t consciously remember all of those details.

Our recollections are less “streaming video” and more “still photograph,” and that has important implications for the customer experience, because what smart companies recognize is that they’re not just in the business of shaping customers’ experiences, they’re in the business of shaping customers’ memories.

Indeed, how customers remember their interactions with you is arguably more important than the interactions themselves. When someone asks you, “What do you think of [Company X] or [Product Y]?” the next thing that comes out of your mouth won’t be based on your experience with those companies or products; rather, it will be based on your recollection of the experience.

That recollection (which will be the basis for your repurchase and referral behavior) won’t be derived from some meticulous calculation of the ratio between pleasantness and unpleasantness. Rather, you’ll be making that judgment based on the snapshots that your memory has captured from the encounter: the peaks and the valleys.

If the experience has relatively more (and higher) peaks, then customers will emerge with an overall positive memory of the interaction. Conversely, if the experience has relatively more (and deeper) valleys, then it will sour the customer’s recollection of the encounter.

This is the cognitive science behind customer experience. To leave a lasting, positive impression on customers, one must influence what they remember, strategically creating peaks in the experience that will outnumber and outweigh the valleys.

Let’s look at an example to see how this works.

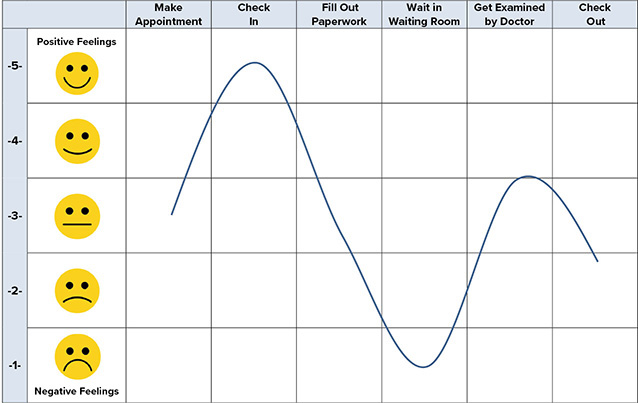

Figure 7.1 is a rudimentary customer journey map. Journey maps are essentially visual depictions of how the average customer feels while interacting with a particular business. In this case, we’re looking at a journey map for the customer experience associated with being a new patient at a doctor’s office.

FIGURE 7.1

Customer journey map for the “new patient” customer experience.

The columns at the top of the diagram outline (in sequential order from left to right) the principal interaction points associated with this customer experience: The new patient first contacts the doctor’s office to make an appointment. Then on the day of the appointment the patient checks in at the front desk, fills out new patient paperwork, waits in the waiting room, gets examined by the doctor, and then checks out at the front desk to pay the bill or make a follow-up appointment before leaving the office.†

On the left axis of the diagram, there is a five-point scale for gauging how the typical customer feels at various points in the experience, from very negative to very positive.

At this particular doctor’s office, things get off to an average start when the new patient first makes an appointment. There appears to be nothing about that interaction that is meaningfully positive or negative.

That changes on the day of the appointment, where an emotional peak is apparent at the point of check-in. Perhaps the check-in area is well adorned, taking on an almost spa-like appearance, and the check-in personnel are extremely bright and cheery.

Then things go downhill. The patient is asked to fill out some paperwork and wait in the waiting room. Whatever’s happening in that waiting room isn’t good, because it’s leaving a very negative impression on the patient. Maybe the wait was excessive, there was poor cell coverage and no free Wi-Fi, or it was crowded without enough seating.

Things improve a bit when the patient sees the doctor, but ultimately the visit ends on a slightly unfavorable note at check-out.

Now here’s the key takeaway: the typical new patient at this doctor’s office will really only remember two things about this experience—the peak (checking in upon arrival) and the valley (waiting in the waiting room). Everything else about the experience will just sort of evaporate from memory and not play a meaningful role in shaping the patient’s impression. (There is one caveat to that statement, regarding how the customer remembers the end of the experience, which we explore in the next chapter.)

The “fragility” of our memories has important implications for customer experience design. It means a business’s customer experience doesn’t have to be perfect. Parts of it could be decidedly mediocre—even somewhat unpleasant—provided there are positive peaks in the experience that will serve as the ultimate memory makers.

Lots of people enjoy going to Disney World, even though the park can feel hotter than the surface of the sun through much of the year, and guests need to wait in long lines to see the attractions. Costco has legions of raving fans, even though finding what you need in the retailer’s cavernous warehouse stores can be quite challenging. Grocery store Aldi is a perennial leader in customer experience rankings, even though patrons must pay a quarter to get a shopping cart (which is refunded when returned) as well as bag their own groceries.

These are all examples of companies whose customers love them, even though there are parts of their customer experience that are far from delightful. They succeed, however, and customers reflect on their patronage positively, because these businesses are creating memorable peaks in other parts of the experience. (We’ll see examples in later chapters about exactly how Disney, Costco, and Aldi create those peaks.)

The challenge, then, when designing and delivering the customer experience is to create more and higher peaks, as well as fewer and less-deep valleys. So, do more stuff well, and less stuff poorly—right? That’s the big secret?

Not quite. Yes, infusing your customer experience with more good stuff (peaks) and less bad stuff (valleys) is obviously a smart strategy to follow. However, there are also more nuanced ways to create peaks and avoid valleys.

Spread the Pleasure

In 2013, Southwest Airlines (an air carrier that routinely tops customer experience rankings) teamed up with Dish Network to offer live, streaming television on its flights.3 The service was simple. Just connect your laptop, tablet, or phone to the aircraft’s Wi-Fi, and you’re ready to stream live TV as well as on-demand content. There was no mobile app to download, no preflight preparation required.

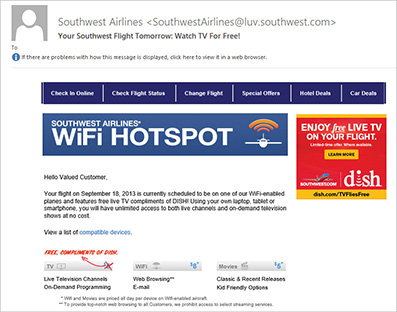

Why, then, did Southwest go through the trouble of emailing passengers (shown in Figure 7.2) the night before their flights, with the jubilant subject line, “Your Southwest Flight Tomorrow: Watch TV For Free!”

FIGURE 7.2

Preflight email communication from Southwest Airlines.

Passengers surely didn’t need to be reminded to bring their mobile devices onboard; most everybody already traveled with those. There was nothing they had to download or purchase in advance. So, why the email?

One might just chalk this up as good marketing, but it’s also smart customer experience choreography. By virtue of messaging passengers the night before, Southwest was essentially creating a second, memorable peak from one element of its onboard experience that it already knew was unique and positive.

Live, streaming TV was not a common inflight entertainment option on US airlines at that time. As such, when Southwest passengers fired up the Wi-Fi and laid back, relaxing, watching live TV, it created a memorable peak in the experience.

The email the night before, by teasing the TV streaming service and creating a sense of anticipation around the inflight entertainment, helped create a second peak, derived from the same experiential feature. That additional peak would be especially pronounced with customers who were new to Southwest and weren’t familiar with the Dish streaming service.

What Southwest essentially did in this example was to “spread the pleasure.” They were not just offering live, streaming TV once onboard. They were also accentuating the service in a preflight communication that created excitement and anticipation. That’s one peak in the experience that gets multiplied by two, thereby creating more snapshots to positively influence the customer’s recollection of their experience with Southwest.

If there’s something that’s already positive in the customer experience you deliver, a component that you know is well-received by your clientele, consider how you can spread that pleasure more widely across the experience. That could involve “parceling out” the good stuff in the experience, such as sharing positive news or developments with your customer in pieces, rather than all together. Or it could be accomplished by strategically reminding your customers of all the peaks in the experience that they’ve already enjoyed, such as a year-end communication recap of all the value they’ve derived from your goods or services.

Compress the Pain

If creating more peaks in the experience requires spreading the pleasure, then minimizing valleys in the experience necessitates the opposite—compressing the pain. By combining unpleasant interactions in the experience, by aggregating the ugliness, it’s possible to turn what could have been multiple experience-degrading valleys into just one bad touchpoint.

Think of it this way: it’s better to put a customer on hold once for six minutes than to put them on hold twice for three minutes. Nobody enjoys being put on hold, and the total hold time in these two scenarios is, of course, the same. But if during the course of the call, the conversation has to be paused twice while the customer is put on hold, that’s going to create two distinct valleys in the experience, each one weighing down on the caller’s impression of the interaction. However, by putting the customer on hold just once (even if it individually is a longer hold), it will feel less onerous to the customer and leave him or her with just one instead of two unfavorable snapshots.

To be sure, the resulting valley can’t be so deep, so agonizing, that it leaves a scar on the customer’s memory from which no recovery is feasible. Put a customer on hold once for 15 minutes, and even though it’s just a single valley, it’ll surely send the individual over the “cliff of dissatisfaction,” as it’s often called. That’s the point-of-no-return in customer experience, where nothing you can do can eclipse the negativity that’s created.

Most every type of customer experience has its share of ugliness—elements that are annoying, aggravating, or frustrating. Once you identify those unpleasantries, explore ways of lumping them together into a single (or at least a smaller) set of interaction points. That way, instead of creating multiple iterations of customer pain, you can limit the duration and intensity of the distress felt by the customer, paving the way for a better remembered experience.

Create Tentpoles

In 2014, the customer insight team at one of the largest publicly traded US insurers pored over volumes of the company’s policyholder survey data in an attempt to answer one key question: What customer touchpoints should they focus on to elevate policyholders’ overall impression of the insurer’s experience?

As they sliced and diced the data every which way, they stumbled across a surprising finding. When policyholders were happy with their insurance agent, they tended to be happier with all other aspects of the insurer’s customer experience—even those that had nothing to do with the insurance agent.

Customers who gave high marks to their agents also expressed greater satisfaction with the insurer’s website, billing statements, coverage parameters, and even premium rates—which are all things that the local agent had no influence on or control over. It was as though the positivity of policyholders’ interactions with their agent “bled” into their perceptions of completely unrelated components of the insurer’s customer experience.

The customer insight team was seeing the impact of what I call the “Tentpole Effect.” Imagine the pole at the center of a circus tent. As you lift the center pole higher and higher, what happens to the rest of the surface of the tent? It rises, even though it’s not directly above the center pole.

This is how our perceptions of an experience work, as well. One very positive part of the experience can actually elevate our impressions of entirely different parts of the experience—like the surface of a tent rising with the center pole, or a tide that lifts all boats.

This concept is a descendant of the “halo effect,” a type of cognitive “confirmation bias” first described by Edward Thorndike in his 1920 paper, “A Constant Error in Psychological Ratings.”4 Thorndike observed that people’s perceptions of others are (inappropriately) influenced by unrelated attributes. For example, we tend to view people who are physically attractive as being more intelligent and knowledgeable than those who are unattractive. One appealing personal characteristic casts a positive glow on everything else, as we have a tendency to see and hear things that confirm our beliefs, rather than refute them.

(The converse is also true. A single negative characteristic can unduly influence people’s overall impressions, leading them to view a person or thing more unfavorably than would otherwise be the case. That’s the “horn effect,” which is the opposite of the halo effect.)

The halo effect bias manifests itself in similar fashion when people are evaluating their customer experiences. An insurer with great local agents gets high marks for its billing practices, even if they aren’t objectively all that good. A retailer with a slick, visually appealing website is viewed as being more reliable and trustworthy than a competitor whose online presence looks more amateurish. An airline with super-friendly flight attendants is perceived as having better on-time performance.

The lesson to be learned here is that it’s important for you to excel in at least one aspect of your customer experience. It could be how you onboard new customers, or your responsiveness to inquiries, or the ease of product installation. Whatever it is, just make sure to create at least one high peak in the experience, because that tentpole will actually make your customers feel better about the rest of the experience you deliver—even if you don’t lift a finger to improve those other parts.

PUTTING THE PRINCIPLES INTO PRACTICE

How to “Create Peaks and Avoid Valleys”

Be deliberate in how you “sculpt” the customer experience, paying particular attention to the creation of peaks (really good parts that people will remember) and the avoidance of valleys (really bad parts that people, unfortunately, will also remember). While that’s obviously an exercise in doing more things well and less things poorly, a customer’s memories of the peaks and valleys can also be influenced by how the experience is sequenced and presented.

• Compress the pain. Make unpleasant parts of the customer experience less memorable by aggregating them into a single touchpoint, so as to avoid creating multiple negative impressions that could weigh on people’s perceptions of the encounter.

• Lump “homework assignments” together. One way of compressing the pain can be found in how you engage customers when you need something that might create a burden on them (giving them “homework,” if you will). For example, if you need customers to fill out forms or complete paperwork, give it to them all at once, rather than “dripping” it on them over a period of time. Similarly, when requesting information from your customers, go to the well once—try to avoid saddling them with multiple inquiries spread out over a period of time.

• Limit the number of steps in unfavorable transitions. Waiting in a waiting room. Having your call transferred to another department. Being put on hold. Navigating through multiple levels of an 800-line menu. These are all examples of transitions in the experience, where customers navigate across touchpoints in a way that (from their perspective) adds little value. In these situations, it’s advisable to minimize the number of transitional steps, as each one might leave a valley-like impression on the customer. In a doctor’s office, for example, instead of making patients wait in a waiting room and then wait again in an exam room, just bring them into the exam room when the physician is ready to see them. Similarly, avoid putting customers on hold repeatedly or transferring their call multiple times.

• Spread the pleasure. Look for ways to amplify and extend favorable aspects of the customer experience by strategically sequencing the pleasurable parts, creating multiple positive peak impressions that will help enhance people’s recollection of the encounter.

• Create anticipation. One way to create additional peaks is through communication that helps heighten the customer’s anticipation for some other appealing part of the experience. For example, you could email customers as the product they ordered is being manufactured, assembled, or customized for them. Or as Southwest did with their livestreaming entertainment, service providers can message customers to preview the benefits they’ll soon enjoy. Either way, the key is to pique customers’ interest in all the goodness they’re about to experience.

• Establish echoes. Peaks can also be spread by creating “echoes”—communications that essentially serve to remind the customer of earlier high points in the experience. For example, you could use a year-end message or an annual stewardship report to recap all of the value you’ve delivered to a customer or that the customer has derived from your products/services during the course of the past 12 months. The same approach can be used with workforce communications to highlight significant individual or team accomplishments, thereby fostering pride and engagement.

• Parcel out the positives. If you have good developments to share with a customer or achievements to celebrate, break the communication up into parts. Instead of highlighting all the positive news once, consider separating the message into parts to create distinct memorable peaks, provided it won’t be confusing as a result. In the employee arena, this translates into “parceling out the praise,” meaning that—for deserving staff—compliments are more impactful if communicated across multiple interactions instead of a single one.

• Do at least one thing exceptionally well. Select one aspect of your customer experience where you will be sure to overperform, creating the tentpole that will help elevate customers’ impressions of the entire encounter. It could be, for example, a particular episode in the experience, such as the purchase interaction or postsale onboarding activities. It could be a particular artifact in the experience, maybe a website, the product packaging, or the ambience created within a physical store. Or it could be an experiential attribute that weaves its way through all customer interactions, such as extremely knowledgeable or friendly staff, or super-fast responsiveness to inquiries.

• Don’t try to peg the needle at every touchpoint. Accept the idea that certain elements of your customer experience might not be outstanding. That’s fine, as long as those parts aren’t memorable, while others (better ones) are. As long as you’re creating some peaks in the experience (and avoiding too many or too deep valleys), it’s all right if certain interactions just leave a neutral impression on the customer. Be intentional, however, about where those neutral impressions are made. They shouldn’t happen during interactions that are especially important to the customer (so-called moments of truth). Nor, as we’ll see in the next chapter, should they occur toward the end of the experience.

CHAPTER 7 KEY TAKEAWAYS

• How people remember their customer experience is arguably more important than the experience itself, since it is individuals’ recollection of these interactions that will ultimately drive repurchase and referral behavior.

• We remember our experiences as a series of snapshots. Not just any snapshots, but rather, the peaks and the valleys in the experience. Everything in between basically melts away from our memories and doesn’t materially influence customer perceptions.

• Cognitive science can be used to sculpt the customer experience in a way that helps cement the memory of good parts, while muting the memory of bad parts. It’s about creating more and higher peaks, as well as fewer and less-deep valleys.

• Peaks can be created not just by doing more things well, but also by taking good parts of the experience and spreading the pleasure to create multiple, memorable peaks from a single positive aspect of the experience.

• The converse is true with the valleys. Their drag on customer perceptions can be minimized by “compressing the pain”—aggregating unpleasant parts of the experience into a single interaction, instead of spreading the pain more widely.

• Peaks are great in and of themselves, but they also provide a halo effect. When you create at least one tall peak in the experience, it actually elevates people’s impressions about the rest of the experience even if no improvements are made to those other parts.

![]()

† This journey map is highly simplified for the purposes of this example. A real journey map describing this experience would need to be more detailed, dissecting the encounter’s touchpoints with greater granularity.