3

On Business Models

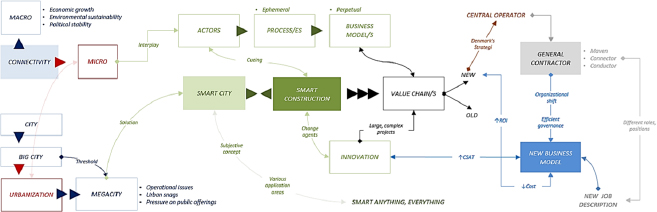

This chapter examines the existing academic literature on business models. This is fundamental because the prime aim of this study is to design a new business model that would be a better fit, say more appropriate for the handling of large construction projects. The business model that we intend to build is that of a general contractor (strategi or central operator) who would be consigned (by a project owner) for the administration of smart developments, from conception until delivery of the final product. Yet, for this to be conceivable, we, to begin, endeavor to comprehend the specificities of business models. We will then search to recognize the various paths to business model innovation. In other words, we intend to describe the rationales based on which companies seek to create and capture value in various settings (economic, social and environmental) and elucidate the process of business model innovation which, we believe, is part of a company’s open set of business strategies. With that said, Chapter 3 is structured as follows:

- – First, the business model notion is clarified – an overview of the most prominent representations of business models is presented – and the relationship between different sets of business model arrangements and value creation is embarked upon.

- – Next, we demonstrate how business models are forthrightly linked to a company’s business strategies and, as a result, are decisive regarding its business tactics.

- – Then, we examine the process of business model innovation, as a means for crafting, applying and authenticating new business models. Also, we pinpoint the major gaps in the research on business model innovation today.

- – Finally, we provide some real-world business model innovation examples. By discussing the best managerial practices that could help executives in general, specifically those in the construction industry, we take business model innovation to the level of a consistent and corrigible discipline.

3.1. Definitions

Almost 30 years ago, following the rise of the World Wide Web in the mid-nineties, the BM (Business Model) concept has been envisaged by numerous authors via distinct subject-matter lenses, and has been gaining ground since then (Zott et al. 2011). It is only after the advent of computers and spreadsheets that BMs became popular (Magretta 2002). Prior to that, successful BMs were created unintentionally – neither by design nor by foresight – and became clear only after the fact. At the outset, BMs were only concerned with e-business (e.g. e-commerce and e-market) and it was only after a short while that the scope of BMs became protracted (Timmers 1998) and BMs were used to assess other phenomena (e.g. innovation and technology management). Indeed, BMs came to be the new basis of competition, replacing product features and benefits as the playing field on which companies emerge as dominant or laggards (Chesbrough and Rosenbloom 2002). Nowadays, the existing literature on BMs suggests the prevalence of four school of thought1 (Zott et al. 2011), explicitly: (1) BM as a central unit of analysis; (2) BM as a system-level, holistic approach to expounding how companies capture value and generate profit; (3) BM as a strategic means to explain both value creation and value capture phenomena; and (4) BM as a platform where the activities of focal companies and their partners are expected to play a key role in the conceptualization of BMs in force.

Moving on, we wonder: What exactly is a BM? In spite of the recent deluge in the literature on BMs, we affirm that a definitional clarity on BMs is still nonexistent today (Zott et al. 2011; Bucherer et al. 2012), and BMs are repeatedly studied without a clear definition of their concept (we remain optimistic nonetheless, trusting that these emerging themes may one day lead to a more fused study of BMs). According to Massa et al. (2017), BMs constitute a key vehicle for innovation at the corporate level – and this, in two ways: (1) by allowing executives to connect innovative products and technologies to a realized output in a market; and (2) by being a distinct source of innovation per se, paired to customary dimensions of innovation (product, process, managerial and others). Likewise, Lambert and Davidson (2013) and DaSilva and Trkman (2014) acknowledged that a BM exhibits how a company generates, conveys and captures value. It underlines the content, configuration and management of the activity system that carries a value proposition to the customer.

For Ferrero et al. (2015), BMs are the method that a company uses for its functioning – encompassing the aim, schemes and persons who join forces to bring added value to customers. A simple case of customer needs being fulfilled by totally distinct BMs, the authors specified, is car transportation. Getting from point A to point B could be served by a car that is either bought, leased, rented or shared. The main product is basically the same, while the activity system underlying the product shields a spectrum of distinct BM design choices. Overall, value capture is enabled by the company’s ability to homogenize and mechanize operations across the activity system – and the purpose is not to add intricacy, but to allow for scalability via simple, operative activity systems.

Going forward, Micheal Lewis in his book entitled The New, New Thing: A Silicon Valley Story2 spoke of BMs as artworks. And like any artistic production, he emphasized, it is one of those things that people sense they could spot at first sight without being able to explain them. Indeed, he suggested the meekest of definitions: “it is how a company plans to make money”. By the same token, Magretta (2002) avowed that BMs are stories – stories that elucidate how companies work. The author declared, “any decent BM would be able to answer the following age-old questions: Who is the customer? What does the customer value? How does the business work? And how could value be delivered to customers at an appropriate cost?” In the same context, Weill and Vitale (2001) recognized that BMs depict roles and rapports among a company’s customers, partners, suppliers and manufacturers. Similarly, Morris et al. (2005) associated BMs with the manner – or the art – of conducting business to ensure the sustainability of the company, providing the following definition: “a BM is a method of doing business by which a company could sustain itself by generating revenues”. “A BM tells how a company makes money by identifying where it is positioned in the value chain”, the authors added.

As for Amit and Zott (2001), a BM describes the content, structure and governance of transactions designed to create value through the exploitation of business opportunities. A BM, they added, is conceived by a company to create and capture the largest market value possible from the products and/or technologies it is commercializing. The quality and the level of the economic outcomes, they concluded, depend on the efficiency of the BM being used. Subsequently, they asserted, “the more a BM is efficient and ingenious, the more the market value of the newly commercialized products, created and captured through it, would be great”. Osterwalder (2004), we proclaim, had a significant contribution in this respect too – defining a BM as a conceptual tool that contains a set of interconnected elements – and allows one to express a company’s logic of making money. In a similar manner, Demil and Lecocq (2010) demarcated a BM as the way a company operates to ensure its sustainability: “Companies should focus on sources of value creation that are inherent in the BM itself and could be accessed through it”.

On another note, Zott and Amit (2010) signposted that BM design is a key decision for start-ups – and a critical, perhaps more difficult one for established companies with prospective plans to redefine their existing business structures. The authors pictured a BM as an activity-system-design framework that encourages holistic thinking (see Table 3.1). As reported, “a BM is geared towards total value creation for all parties; the greater the total, the greater the company’s bargaining power, and the greater the amount of value it could appropriate; it is a template of how a company conducts business and how it delivers value to its stakeholders.”

Table 3.1. Table 3.1. An activity system design framework

(source: adapted from Zott and Amit (2010))

| Design Elements | |

| Content | What activities should be performed? |

| Structure | How should they be linked and sequenced? |

| Governance | Who should perform them, and where? |

| Design Themes | |

| Novelty | Adopt innovative content, structure or governance |

| Lock-In | Build in elements to retain business model stakeholders |

| Complementarities | Bundle activities to generate more value |

| Efficiency | Reorganize activities to reduce transaction costs |

A fairly comparable definition can be found in Demil et al. (2015): “a BM enlightens the logic of a company, the way it operates, and how it creates and captures value for its stakeholders.” Table 3.2 lists some other prevalent definitions suggested for BMs.

To finish, we say, given the scope of our book and the objectives assigned to it, we choose to adopt Timmer’s (1998) definition of BMs; also, to some extent that of Demil et al. (2015). As we see it, BMs are meek strategic tools that companies resort to, to better depict the relationships they hold with different actors (suppliers, customers, etc.) along the industry value chain. These tools, we affirm, enable companies to better visualize the practices through which they capture and create value. From our perspective (as an expert in the French construction industry), a BM is a give-and-take, looping process that describes a company’s moneymaking rationale.

Table 3.2. BM definitions

(source: compiled from various sources)

| Definition | Author/s |

| The BM is an architecture of the product, service and information flows, including a description of the various business actors and their roles; a description of the potential benefits for the various business actors; a description of the sources of revenues. | Timmers (1998) |

| The BM is the heuristic logic that connects technical potential with the realization of economic value. | Chesbrough and Rosenbloom (2002) |

| BMs consist of four interlocking elements, which, taken together, create and deliver value. These are customer value proposition, profit formula, key resources, and key processes. | Johnson et al. (2008) |

| A BM is a reflection of the company’s realized strategy. | Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart (2010) |

| A BM articulates the logic, the data and other evidence that support a value proposition for the customer, and a viable structure of revenues and costs for the company delivering that value. | Teece (2010) |

| A BM is a meta concept to exemplify the business strategy of a company. There are four components of a BM: customer, customer engagement, monetization and value chain, and linking mechanisms — which aim at capturing the essence of the cause-effect rapports between customers, the company and money. | Baden-Fuller and Mangematin (2013) |

The next section delves into the main constituents and représentations of BMs – exactly as found in the literature stream on BMs.

3.2. Constituents and illustrations

The Internet was the prime driver that led to the growth of interest in BMs – and the resulting rise of an extensive literature that spins around the topic (Magretta 2002; Yip 2004). In fact, the number of e-business scholars who aimed to differentiate between primary- and secondary-class3 areas of BMs’ constituents has significantly grown over time. A listing of those is available in Table 3.3.

Table 3.3. The constituents of business models

(source: adapted from Zott et al. (2011))

| Primary-class areas | Secondary-class areas | Author/s |

• Value stream for partners and buyers network • Revenue stream • Logistical stream | n/a | Mahadevan (2000) |

| • Profit stream | • Customer selection • Value capture • Differentiation and strategic control • Scope | Stewart and Zhao (2000) |

• A system made of components, linkages between components, and dynamics • Customer value • Revenue sources | • Scope • Price • Connected activities • Implementation • Capabilities • Sustainability | Afuah and Tucci (2001) |

• Mission • Structure • Processes • Revenues • Legal issues • Technology | • Mission: goals, vision, value proposition • Structure: actors and governance, focus • Processes: customer orientation, coordination mechanism • Revenues: source, business logic | Alt and Zimmerman (2001) |

• Concept • Capabilities • Value | • Concept: market opportunity, product and service offered, competitive dynamics, strategy for capturing a dominant position, strategic options for evolving the business • Capabilities: people and partners, organization and culture, operating model, marketing sales model, management model, business development model, infrastructure model • Value: benefits returned to stakeholders, benefits returned to the company, market share and performance, brand and reputation, financial performance | Applegate (2001) |

• Sustainability • Revenue stream • Cost structure • Value chain positioning | n/a | Rappa (2001) |

• Value proposition • Customer segments • Partners’ network • Delivery channel • Revenue stream | • Relationship • Value configuration • Capability • Cost structure | Osterwalder (2004) |

• Products and services delivery • Customers • Costs structure • Income | • Network • Network externalities | Bonaccorsi et al. (2006) |

• Costs • Revenue stream • Sustainable income generation • Goods and services production and exchanges | • Pricing strategies • Relationships • Network externalities | Brousseau and Penard (2006) |

To make a long story short, scholars (Amit and Zott 2001; Lucking-Reiley and Spulber 2001; Afuah 2004) who concentrated on e-business as an area of research on BMs have been interested in understanding the functioning and operability of companies engaging in unusual, Internet-based ways of doing business – as well as in the first-hand roles that those companies could play in their respective ecosystems. To do so, they have invested lots of time and effort in defining and representing generic BMs, rather than propose causal justifications or conduct empirical analyses. Their descriptive contributions, we assert, highlighted, to some extent, the notion of value (customer value, value proposition and others), financial aspects (e.g. revenue streams and cost structures) and other elements associated with the architecture of the network between the company and its partners (delivery channels, network relationships and others).

As per Zott et al. (2011), each of these constituents are possibly to account for part of a generic BM, and could help scholars set different arrangements (types) of BMs apart. In fact, the authors added, a BM is neither a value proposition, a revenue model, nor a network of relationships per se – but instead is all of these elements combined.

Up until now, many academic researchers have tried to embody BMs via a blend of informal textual and/or purposeful graphical illustrations. Weill and Vitale (2001), for instance, presented a set of simple graphics envisioned to provide tools for the study and design of e-business initiatives. The graphics of their BM focused on three classes of matters: participants, rapports and flows.

Equally importantly, Tapscott et al. (2000) suggested a value mapping approach to portray how a business web actually works. The latter shows all key classes of participants and value exchanges between them – and exhibits the shape and nature of a BM, thus enabling companies to run plausible BM simulations before engaging in real-life projects. Other scholars have provided a BM ontology – being a conceptualization and validation of the elements, rapports and lexis of a BM (Osterwalder 2004), organized into several stages of decomposition with snowballing levels of complexity. In the same manner, Gordijn and Akkermans (2001) came up with a conceptual modeling approach for the representation of BMs. Their ontology scrounges notions from the business literature (actors, value exchanges and activities, and others) – and uses them to model networked assemblages of companies and end-users who create, dispense and consume things of economic value.

The upcoming sections list and explain four noticeable BM representations as well as clarify how those representations (not all, but some of them!) serve the purpose of our empirical research in this book – and to what extent.

3.2.1. Business model canvas

Osterwalder’s (2004) conceptual tool encloses a set of interrelated elements, which set the path to the clear-cut expression of a company’s BM. As indicated by the author, “it is implausible for companies to be able to develop or design innovative and effective BMs unless they pay thorough attention to their constituents”. The competent conception of a new BM – whether a company intends to redesign or reinvent an existing BM, or even create an entirely new one – is indisputably a tricky event (Gassman et al. 2014).

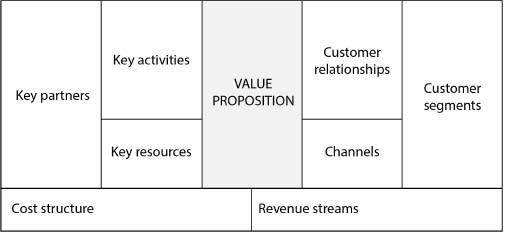

Overall, companies often use Osterwalder’s BM canvas as aid to develop new BMs – or to help analyze and map existing ones. Originally, the latter was inspired by the works of various scholars (Afuah and Tucci 2001; Amit and Zott 2001; Applegate 2001; Weill and Vitale 2001; Chesbrough and Rosenbloom 2002; Magretta 2002); specifically, Osterwalder (2004) identified the building blocks of existing BMs – as exhibited in the literature, then synthetized and conceptualized them, and then put them together to create one puzzle, a distinctive BM (Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1. Osterwalder’s business model canvas

(source: adapted from Osterwalder (2004))

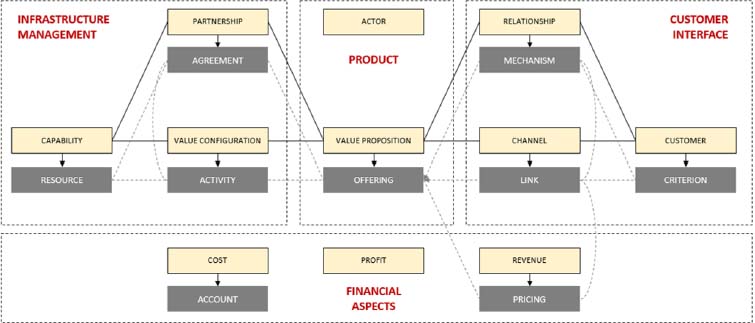

If we focus in on the BM under examination, we get a vision of the latter’s ontology (Figure 3.2), that is, a detailed sight of the various elements and rapports describing the money-earning logic of a company. Largely, the ontology comprises nine building blocks, the so-called BM elements, where each element (e.g. the value proposition) could be broken down into a distinctive sub-element (e.g. the offering). This breakdown allows for the reconsideration of BMs on different levels of granularity and based on particular needs. Indeed, in order to better comprehend value and to construct innovative offerings, Osterwalder (2004) suggested a conceptual (systematic) approach outlined in the value proposition element that makes value innovation easier. This, according to the author, would enable companies to identify and map their existing value proposition and compare it to that of their rivals. Osterwalder’s BM, we stress, revolves around one dominant notion: value proposition. It is the first and most central of the nine elements of BM ontology, perceived as the declarations of remunerations that are transported by the company to its external populations (Bagchi and Tulskie 2000). Plainly, value proposition denotes how items of value are swathed and offered to satisfy customer needs; it describes the way a company sets itself apart from the competition and is the main reason why customers choose to deal with one company instead of another4.

Figure 3.2. Osterwalder’s business model ontology

(source: adapted from Osterwalder (2004) and Osterwalder et al. (2005)). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/karam/general.zip

By itself, Osterwalder’s BM canvas is global and comprehensive, at least from an economic standpoint. This is accurate as it covers all BM elements spread along the value chain, up- and down-stream – going from the company’s dealings with partners to production activities, bearing in mind the availability of resources (infrastructure management) – and then protracting to shield the logistics needed for the commercialization of products or services to targeted market and customer segments (customer interface). Also, it helps a company ensure a better trade-off between its cost structures, on the one hand, and its revenue streams, on the other hand (financial aspects). The limit of the model, nevertheless, lies in the fact that it is profit-oriented, solely focusing on the economic aspect of business activities, hence overlooking some other, equally important aspects, for example, those that are social and environmental.

3.2.2. Causal loop diagram

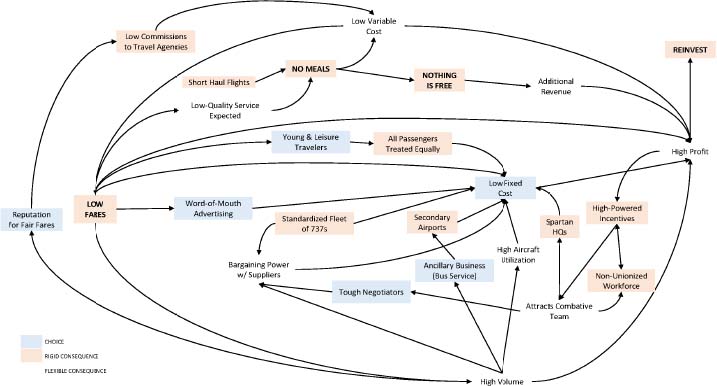

Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart (2007) indicated that developing new BMs would enable companies to strengthen and sustain their current market positions by developing and implementing new products, services or even technologies. The authors praised the inductive perspective to building BMs in general – through a CLD (Causal Loop Diagram)5. “A BM consists of different part sets”, the authors professed, “and the choices made on how the company should operate – and the prospective consequences that might ensue from these choices are interrelated [...] which infers that every corporate choice made would inevitably lead to some consequences, one or more, positive or negative”. Indeed, as put by Kiani et al. (2009), CLD is a valuable tool that helps companies capture the gestalt of BMs and provide executives with significant insight into BMs to better apply them. BMs, they said, show how companies operate by choosing how to liaise with their adjacent environments.

Looking at Figure 3.3, Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart (2011) divulged that corporate decisions are threefold. First comes policy choices, which slot in all means of action that a company employs to cover the different facets of its operations. Asset choices follows, invoking decisions made vis-à-vis tangible resources. Third and last, there are the governance choices, which designate the structure of contractual arrangements that confer decision rights over policies and assets. In order to better elucidate the imbrications of choices versus consequences, the authors gave the example of the BM of a company that operates a fleet of trucks (asset choice). The company, they said, has a governance choice to make between buying and owning the trucks, or leasing and operating them. No matter the company’s choice, they added, the decision made, true or false, right or wrong, would potentially pointedly sway its ability to create and capture value, positively or negatively.

Figure 3.3. Elements of a business model

(source: adapted from Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart (2011))

Table 3.4. Ryanair: choices and consequences

(source: adapted from Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart (2011))

| Choices | Consequences |

| Secondary airports | ↓ Airport fees |

| ↓Tickets prices | ↑ Volume |

| ↓Commissions to travel agents | ↓ Cost |

| Standardized fleet of 737s | Bargaining power with suppliers |

| Single-class | Economies of scale |

| High-powered incentives | Attracts combative team |

| No meals | Faster turnaround |

| Nothing free | ↑ Revenue |

| Spartan headquarters | ↓ Fixed cost |

| No unions | Flexibility in rostering staff |

Figure 3.4. Ryanair’s (low-cost strategy) business model

(source: adapted from Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart (2011)). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/karam/general.zip

Ryanair6 is another great real-world example that exhibits how a company could use CLD to depict its own operating BM. Table 3.4 summarizes the choices made (or the business strategies opted for) by Ryanair versus the consequences that later ensued as a result of these choices – which eventually resulted in the creation of the so-called Ryanair BM – also known as Ryanair’s low-cost strategy BM. According to Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart (2010, 2011), it is the recurrent process of dotting the causality linkages between various choices and consequences that would convert a company’s BM into a CLD (Figure 3.4). “The choices made and the suing consequences are creators of BMs”, the authors added. “And the rigidity or flexibility of a given consequence is measured by its elasticity or inelasticity to the variations in the choices made.”

Before we jump on to explaining the RCOV framework, we end this section by mentioning that the logic behind the CLD is partially espoused in our empirical research to build and conceptualize the stage-based construction process map, a piloting tool by which we mark all the potential connections among and within the elements of our envisioned BM.

3.2.3. RCOV framework

Similarly to other scholars, Demil and Lecocq (2010) contemplated BMs from a configurational viewpoint, and came up with the RCOV framework (Figure 3.5) which is currently one of the most cited representations in the academic literature on BMs. Because of its dynamism, features and parsimony, the latter seems to have a certain edge over other comparable BMs. The RCOV model was first known as the RCOA model (Lecocq et al. 2006; Demil and Lecocq 2008) but as a result of subsequent refinement, it took a new form and was therefore labeled otherwise. RCOV stands for Resources & Competences (RC), Organization (O) and Value proposition (V), denoting the three basic elements of the BM under examination, whereas RCOA is short for Resources & Competences (RC), Offerings (O) and Activities (A).

In a broad sense, the RCOV model follows a defined logic that could be precised in the following manner: a company builds its BM by making various choices to generate revenue from different sources. And the choices made comprise a chain of resources and competences to be valued, namely: a business-to-customer value proposition and the business organization per se, internal and external. Moving forward, the resources and competences are valued through the supply of products or services on markets. The organization, on the other hand, refers to the set of operations that a company deals with and chooses from (value chain) and the associations it holds with other stakeholders or partners (value network).

Figure 3.5. RCOV framework

(source: adapted from Demil and Lecocq (2010)). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/karam/general.zip

The model’s three basic elements determine the structure and the size of costs and revenues of a business and therefore its profit margin, as well as the sustainability of its BM. The cost structure is driven by a company’s organizational configuration, while the revenue structure is based on the exclusivity and appeal of the products or services it offers to its customers.

To summarize, we note that, while the customer is not a direct part of the RCOV model, it is – or at least may be – a constituent of a company’s external managerial structure, thus part of one of its main elements (Organization). This is important because customers are certain to play a decisive role in the success (or failure) of a company’s BM. Thus, incorporating customers into a company’s BM is crucial, both in theoretical and practical terms. A comparable proclamation was repeatedly made throughout this book (see Chapter 1) to underline the pivotal role that people (a primary smart city component) could play (as producers of data and value) in the conception and design of successful smart cities. Moreover, based on the RCOV framework, it is sort of palpable that the positioning of a given company within the value network is critical for its long-term business success; also, the way the latter chooses to integrate both Resources & Competences components in its own BM would eventually sway its organizational structure and influence its ability to create and capture value:

Recapping, the TLBMC (triple layered business model canvas) constitutes the foundation of our envisioned solution-based BM, which aims at identifying the main problems faced at the construction industry level – as well as at suggesting actionable insights as to what the possible solutions might be. The CLD on the other hand informs the carcass of our piloting tool. Through dependency graphs, the latter would enable construction companies to track their works every step of the way. As for the RCOV framework, we take the rationale behind it, especially its R-C-O components, to further elucidate the budding changes in our new BM.

Now that we have defined BMs, demarcated their integral components, and explained their conceptual representations, the next section identifies different business model arrangements that describe and clarify the various ways companies engage with stakeholders to create and capture value.

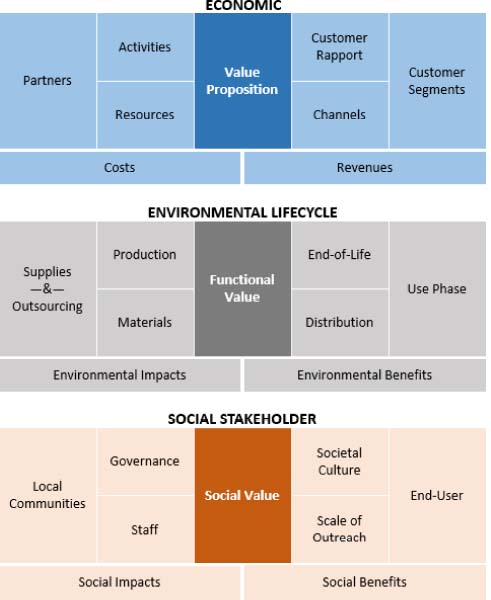

3.2.4. Triple layered business model canvas

Pigneur et al. (2015) expanded on Osterwalder’s BM canvas – which consisted of only one layer (economic) – by adding two extra layers to it: environmental and social, thus rendering it more sustainable and customer-integrated (Figure 3.6).

As per Sherman (2012), these supplementary layers parallel Osterwalder’s BM canvas by underlining the interconnections, which support environmental and social impacts disjointedly, and lengthen it by drawing links across all three layers to bear a cohesive triple bottom line perspective of managerial impact. The TLBMC (triple layered business model canvas) is one of the best strategic management tools that companies can use to explore the sustainability of their new BMs, as it explicitly shows how they could bring value to their businesses (Abraham 2013). The said BM representation is interesting by itself because it did well by converting a profit-oriented BM (Osterwalder’s original representation) into a human-centric one. At its core, the TLBMC promotes a shift from incremental and secluded innovations towards more integrated and complete sustainability-oriented innovations, which, we trust, are better suited to meeting ongoing international crises, and energy and factor constraints (Adams et al. 2015).

As a tool, the TLBMC bridges business model innovation (Spieth et al. 2014) and sustainable BM development (Boons and Lüdeke-Freund 2013), and helps companies overcome barriers to sustainability-oriented change (Shrivastava and Statler 2012; Lozano 2013) by allowing them to creatively rethink their current BMs and communicate potential innovations.

Furthermore, as a multi-layer BM canvas, the TLBMC endows companies with a clear and somewhat easy way to visualize and discuss the multiple and diverse impacts of their BMs. Therefore, instead of attempting to condense multiple types of values into a single canvas, the TLBMC allows companies to explore economic, environmental and social values in a bidirectional manner, horizontally and vertically, among and within layers (and building blocks). Simply put, the TLBMC provides a concise framework to encourage visualization, communication and collaboration around innovating more sustainable BMs (Boons and Lüdeke-Freund 2013). In contrast to Osterwalder’s BM canvas, the TLBMC offers companies the opportunity to address a triple bottom line where each canvas layer is dedicated to a single dimension, and together they provide a means to integrate the associations and impacts across layers.

Putting the economic layer aside, the environmental layer of the TLBMC, as mentioned by Abu-Jbara (2019), stems from research and practice on LCA (Lifecycle Assessments), which offers an assessment of environmental impacts across multiple types of indicators over the entire lifecycle of a product. Linking LCA to business innovation may possibly support competitive product and business model innovation, and hearten continuing impact measurement and improvement of sustainability-oriented innovations over time (Chun and Lee 2013). With regard to the TLBMC’s social layer, it strives to balance the interests of a company’s stakeholders rather than just focus on profit maximization. Much like the environmental layer, the social layer extends the original BM canvas by scrutinizing a company’s BM based on a stakeholder perspective (Mitchell and Coles 2003). Upon reexamining Figure 3.3, we recognize that the TLBMC’s environmental layer revolves around one chief element, the functional value, which defines the focal output of a product or service delivered by a company. The social value, on the other hand, is the TLBMC’s social layer’s chief element, and relates to a company’s mission which focuses on creating advantages for both its stakeholders and the society as a whole.

Figure 3.6. The triple layered business model canvas

(source: adapted from Pigneur et al. (2015)). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/karam/general.zip

As far as we are concerned, for the purpose of this book, we choose to adopt the TLBMC as a means or strategic tool for conducting BM analysis and innovating towards a more sustainable, human-centric BM in construction (that of a general contractor for the managing of smart developments). The TLBMC, we believe, constitutes the foundation for our envisioned BM, which accounts for smart city components (people, living, governance, economy, mobility and environment). The similarities between smart city components (on the one hand), and the TLBMC’s layers and building blocks (on the other hand) are obvious, even at first sight; hence our choice of BM canvas (continue reading for more details in this regard).

3.3. Business model arrangements and value

This section builds on various insights on customer7 value to identify the different sets of arrangements (types) depicted in BMs that describe how companies prompt value creation (for customers) through value networking (with partners). The most relevant filament of the literature that links with our research goal is the conceptual approach, which gives value a chief role (Teece 2010) and sees the BM as a hasty and simple illustration (see previous sections) of how companies generate financial earnings (Chesbrough 2010; Baden-Fuller and Haefliger 2013).

As formerly noted, the BM literature which was, customarily, to some extent, regardless of the reasons, careless about customer value (Pauwels and Weiss 2008; Osterwalder and Pigneur 2010; Zott and Amit 2010; Zott et al. 2011) has now become (unsurprisingly!) more and more customer-oriented (Baden-Fuller and Haefliger 2013):

The evolution of the smart city concept followed a somehow similar path. After the advent of the World Wide Web, the modern city archetype has become a mere technology demonstrator – and it is only recently that it became people-centered, conceived, and administered following a bottom-up approach.

The main idea conversed herein borrows from the marketing literature (Vargo and Lusch 2004; Gronroos and Voima 2013), spins around the fact that customers have become co-producers of value, and comes hand in hand with the sociological view that value creation necessitates social construction (Pinch and Bijker 1984):

These assertions fit perfectly with the rationale behind our envisioned BM, where end-users – as creators of innovation – are expected to play a vital role in the building of smart cities and the handling of smart construction projects.

We take these ideas as given, and explore the first pair of BM dyadic arrangements (Baden-Fuller et al. 2017) for the co-creation of value: product BM versus solution BM. Yet, before we delve into an explanation of these, we reasonably start by settling on what value is. For this research, we assume value to denote use-value, standing for the utility that customers may gain from using a particular product or service. This is because, as put by Vargo and Lusch (2004), a product or service is considered worthless unless the customer could (literally!) use it or do something beneficial with it, for enjoyment or any other purpose.

The PBM (Product Business Model): when use-value activities are performed, succeeding the act of purchase, and away from the provider. In such a case, the providers’ arrangements for engaging with customers are labeled the PBM (Baden-Fuller et al. 2017). Even though this conception of the product and its use-value is captured in the sphere of the final customer only, the exact same logic could also apply to a middle agent representing the final customer – such as in business-to-business situations where an actor in the value chain may step on the scene on behalf of the end-user.

The SBM (Solution Business Model): when the provider directly engages the final customer in the production process, resulting in the latter’s use-value being co-created. This situation is labeled the SBM (Gronroos and Voima 2013; Baden-Fuller et al. 2017). From the standpoint of the provider, the skills and assets needed to produce a solution are not the same – being far greater than those required by a product. In such a setting, the end-user is more involved in the process and sometimes forced to change their demeanor to fit new situations. We add that an SBM is said to be meaningful to the end-user – but if and only if the ensuing use-value is larger than that gotten from the PBM:

Our envisioned general contractor BM is human-centric, based on the active involvement of end-users throughout the whole project management construction process, as data providers and creators of innovation. Unmistakably, the PBM relates to the old construction value chain where construction companies tend to care more about the expected value of their profit margins and less about the well-being of their customers and the quality of their deliverables. In contrast, the SBM bears a resemblance to the new construction value chain, involving a central operator who will oversee the resourceful running of construction projects and ensure end-users are engaged every step of the way.

In the first pair of BM arrangements (the product- and solution-based BMs), there are only two players involved in the process of value creation. However, in certain cases, when the product is far more complex, there might be more than just one provider on stage, thus transforming the dyadic rapport into a triadic one. This is mainly the case of paired providers, selling complementary products (printers on one side, and paper and ink on the other). In such a case, the essential dyadic, two-player rapport remains unchanged – because only one final customer would ultimately benefit from use-value when all the elements have been put together (Teece 2010).

Our distinction between dyadic and triadic BMs echoes the literature on technology strategy – particularly the contributions of Zott and Amit (2010) and Thompson and MacMillan (2010), who disclosed that companies could have access to several value networks – meaning that technology has endowed companies with new forms of value creation gears, which are orchestrated in the sense that value is currently being created together, by a company and a surfeit of partners – for multiple end-users.

Now sliding to the triadic BM arrangements, we note that there are two of them (Baden-Fuller et al. 2017): the matchmaking BM and the multisided BM, explained below.

The MMBM (Matchmaking Business Model): involves three players: the company that arranges the market (the platform owner) and two customer segments, buyers and sellers who trade an underlying product or service. If we take the case of Uber for instance; Uber, being the matchmaker, would be behind value creation. For buyers (the persons looking for rides), the condensed search time and effort to find a ride means that they may enjoy greater use-value from the service provided via the matchmaker. For Uber, this increase in use-value is a source of potential yield. As for the sellers, they are paid on a ride-by-ride basis – therefore, the more rides they achieve (the more buyers they serve), the bigger their pays will be.

The MSBM (Multisided Business Model): entails three or more players, where the company (the platform owner) creates a set of dealings among two or more otherwise detached customer segments. The first customer segment is called the customer beneficiary; they receive a set of products or services at a trifling price, paid for by a second segment called the paying-customer who profits from creating value for the consumption of the first segment. Central to this BM is the win-win process by which the two customer segments are brought together, as follows: the paying customer profits from the customer beneficiary, using the product or service, and the customer beneficiary profits from the presence of the paying customer, paying for the product or service. Specialized magazines offering the option of free-of-charge advertisement constitute a great example of an MSBM arrangement (see Table 3.5 shown below for a quick overview of all four BM arrangements).

We finish by affirming that the list of BM arrangements exposed herein is extensive, yet non-exhaustive; also, we point out that technology has no objective value by itself and remains latent until it is commercialized via a competent BM (Chesbrough 2010). Indeed, according to the author, BM change is not solely driven by technology, but also by how we think and why we think that way; therefore, in most cases, managerial processes must be changed too.

Do you remember the case of Songdo City in South Korea, where technology has been broadly used to improve the capital product (the creation of a smart city), but failed to do so? In this case, technology did not bring any value at any level; the final product, a mere demonstration of technology, has been deemed unusable and unlivable, and so, no value has ultimately ensued from it, neither for construction companies nor for the citizens of the city. In opposition to South Korea’s experience, capital products are now being offered on an SBM basis with noticeable improvements in value for end-users (Baden-Fuller et al. 2017). It is in line with our envisioned BM, centering on managerial rather than solely technological perfections:

Our envisioned BM follows a two-sided dyadic, solution-based arrangement – encompassing three key actors: the general contractor (the construction company, a middle agent, a conductor) and two different customer segments, up- and down-stream the construction value chain – the project owner (first customer, represented by the general contractor) and the end-user (final customer).

Before we embark upon business model innovation, we reserve the following few sections to clarify the nuances between the two notions of business strategy and business model, and extend our investigation to cover business tactics too. On the surface, these notions seem to be identical – yet, in fact, they are not, and are different constructs (Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart 2010). As put by the authors, a business model is a reflection of a company’s realized strategy; “it is the direct result of strategy, but it is not strategy itself”. By the same token, Magretta (2002) acknowledged that a business model is not the same thing as a strategy, despite the fact that many people use both terms interchangeably today. A business model describes, as a system or platform, how the pieces of a given business fit together, but it does not factor in one critical dimension of performance (e.g. competition). In reality, every company is expected to run into rivals at one point in time and, when it does, it will be the job of the business strategy to deal with it8. And so, we assert that by clearly separating the realms of strategy, business models and tactics, we would have access to an integrative framework based on which better business models could be built and further progress in the field of business model innovation could be made.

Table 3.5. Fundamental business model arrangements

(source: adapted from Baden-Fuller et al. (2017))

3.4. An amalgam of strategies and tactics

A BM, we recap, is a simplified representation of how a company makes money (Casadesus-Masanell and Tarzijan 2012). Referring to the decision-making model shown in Figure 3.7 below, it seems quite evident that it is the fundamental set of decisions that form the business and allow for its continued existence and profitability (Lee and Stinson 2014).

Figure 3.7. The decision-making model

(source: created by the author – inspired by Lee and Stinson (2014)). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/karam/general.zip

Essentially, a company’s business plan documents these key decisions, adding information that supports the alternatives chosen and demonstrating a viable BM. After viability, the company should identify how to sustain its operations in the face of rivalry (Massa and Tucci 2014).

As per Magretta (2002), choosing a competitive-advantage strategy typically identifies the areas where the company should focus its innovation (or investment) efforts to boost customer value proposition over time. To incorporate the concepts of strategy, BM and tactics however, we set off by introducing the generic two-stage competitive process framework (Figure 3.8). The rationale behind the latter, we add, is quite straightforward; it is as follows: normally, companies start by choosing a logic of (strategy for) value creation and value capture, which would be reflected in their BMs. Later, they make tactical choices driven by their intents to maximize stakeholder value. Therefore, sequentially, strategy comes first and tactic follows; and the BM falls in between the two. With that said, we use the term stractics in the next sections to denote BMs, being concurrently a reflection of a company’s sets of strategies and an influencer of its sets of tactics.

Figure 3.8. The generic two-stage competitive process framework

(source: adapted from Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart (2010))

3.4.1. Strategies

A strategy is defined as a provisional plan of action intended to realize a precise objective. It is the art of creating value (Normann and Ramirez 1993). Moreover, as described by Eisenmann (2002), a critical element of strategy is the set of committed choices made by management. Similarly, Porter (2001) points out: “strategy is the creation of a unique and valuable position, involving different sets of activity systems”.

In line with the aforementioned, in this book strategy refers to the provisional plan for which BM to use and at what point to use it. The word provisional is of great significance here, indicating that strategies include provision for eventualities that may not even arise. For example, a given company (Y) facing a potential entrant (X) in the industry would normally have as a strategy, a plan (A) as to what to do if (X) enters the market; a plan (B) as to what to do if (X) refrains from doing so. Assuredly, only one of the two options would actually take place, thus forcing (Y) to take necessary action. However, in the case of an outsider looking at (Y), as reported by Chesbrough and Rosenbloom (2002) and by Johnson et al. (2008), they would only be able to perceive the company’s realized strategy (A or B), not the complete one (A and B).

Returning to the case of Ryanair, when the company was on the brink of bankruptcy back in 1991, its strategy was an action plan to transform its standard full service airline BM. Rivkin (2000), in his article “Dogfight over Europe: Ryanair (A)” richly describes the four alternative action plans that Ryanair’s executives opted for to escape the imminent collapse of this business: (1) become the airline operator of the southwest of Europe; (2) add a business class; (3) become a feeder airline operating from Shannon airport; or (4) exit the industry. Aside from the fourth option, we believe all of the others demanded a different BM, and the specific way Ryanair executed these plans was through one realized strategy linked to one specific BM.

3.4.2. Tactics

Tactics (in comparison to strategies) describe the remaining choices available to a company by virtue of the strategy, and so, the BM currently in use. Consider the case of Metro, for instance, the world’s largest newspaper in circulation (Khanna et al. 2007; Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart 2010). It is free and ad-sponsored (advertising-sponsored) and is published in over one hundred cities. In each city it enters, it competes with local newspapers sold at positive prices. As the Metro is ad-sponsored, it specifies the rates it charges to companies wishing to advertise in it. Metro also chooses the exact number of pages that each edition of the newspaper has, the exact number of ads, the precise balance between news and opinion pieces and so on and so forth. All of these choices are part of Metro’s tactics. However, Metro cannot amend the price of its product because its BM is ad-sponsored, and therefore, the product must be given away for free. In other words, Metro’s BM prevents the company from using newspaper price as a parameter that could be altered depending on level of competition and other external factors. For that reason, we conclude, the latter is not part of Metro’s set of tactics.

Now, we proceed by enquiring: Why are tactics essential anyhow? They are because they play a crucial role in determining how much value is created and captured by the company (Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart 2010). In the case of Metro, advertising rates and the number of ads displayed in the newspaper ended up influencing readership-and-advertising revenues. In fact, as progressively more ads were included, readers became increasingly annoyed and less disposed to reading the newspaper. Equally, as the advertising rates rose, the count of advertisers wishing to advertise in the newspaper plunged, thus crushing Metro’s revenue, profit and value capture:

To further illustrate the essentiality of tactics in the business world, we raise the case of cars – where the car itself designales the BM. Certainly, the way the car is built places constraints on its use-value that is, what the driver could or could not do with it. A large, powerful 4×4 car, for instance, makes it stiff for a driver to maneuver on the narrow streets of the city of Paris. In contrast, a small, powerless compact car would create more value for the driver by making this task far less cumbersome. Thus, under specific settings, there are tactics that are possible with the compact car that would be impossible with the 4×4. Put differently, we conclude that the shape of the car – being an element of the BM – is decisive, in some particular cases at least, of its use-value and so, its overall worth.

So far, we have argued that tactical choices define how much value is created and captured by the company using them – however, as per Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart (2010), there is still much more to tactics than this – with their influence, the authors alleged, reaching out, now and then, to other companies with which the focal company interacts. At this level, we are referring to the idea of tactical interactions, which denote the various ways companies influence each other by acting within the bounds set by their respective BMs. Generally, tactical interactions arise when a company’s BM is put in contact with that of another company (e.g. mom and pop stores and discount retailers)9. And when this materializes, there would be consequences on both companies’ BMs – where feedback to the rest of the system is dogged not only by the focal company’s tactical choices, but also by those made by the other company (McGrath 2010).

Finally, we affirm, a BM employed by a company determines the set of tactics available for it to compete against, or to cooperate with, other companies in the marketplace. Therefore, BMs and tactics are closely related and mutually dependent, with the likelihood of one influencing the other (Yip 2004).

3.4.3. Stractics

Having introduced the notions of strategies and tactics (and earlier, BMs), we – once again – use the generic two-stage competitive process framework to conceptually integrate and relate them (see Figure 3.9). As described by Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart (2010), BMs are presumed to lie in between strategies and tactics. And the linkage between the two concepts is called stractics, a real-world terminology that we use in our text to designate the amalgam of strategies and tactics at the corporate level.

Precisely so, it is a company’s choice of a strategy that would depict which BM to espouse – and so, which set of tactics to apply based on circumstances and needs. As formerly noted, a strategy is a provisional plan of action as to which BM to use, and the available actions for strategy are choices that constitute the raw material of BMs. Based on the strategy, companies define long-term goals and ways to fulfill them. Consequently, strategy entails designing (redesigning) BMs to allow for companies to reach their prefixed durable business objectives. With regard to BMs in particular, they are nothing but a plain reflection of a company’s realized strategy. As for tactics, much like strategies, they are concrete action plans, courses of action that occur within the bounds drawn by the company’s BM. Nonetheless, in contrast to strategies, tactics are generally oriented towards smaller steps and shorter timeframes.

Within this framework, and to better cement the prevalent dependencies between all three notions, we recall the car example put forward earlier – but this time, we suppose that the driver has been given the chance to bring all the changes he wants to the car (e.g. color, fuel consumption capacity, power engine and others) prior to operating it. Business-wise, the changes made (one or more, minor or major) symbolize strategies because they ipso facto alter the car (BM) in its entirety. And the company’s competitive process framework would discharge in the following manner – in order:

- – (1) the design and building of the car are the strategy;

- – (2) the car itself is a BM; and

- – (3) the driving of the car is the tactics.

This reasoning relates to our research project in so many ways. Mainly, by the fact that what we are proposing is an industry-level BM change, an organizational innovation (a new business strategy) that construction companies may opt for to better manage smart developments. Also, given that construction companies may have one or several BMs (moneymaking logics), we, through this study, offer them one more, plainly, a new set of stractics they could rely on for the resourceful achievement of their smart construction projects.

Figure 3.9. Strategy, business model and tactics

(source: adapted from Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart (2010)). For a color versionof this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/karam/general.zip

The upcoming sections present a lengthy primer on the passage from BM to BMI (Business Model Innovation), describe the four main streams of research on BMI and underscore the main gaps in the research on BMI today.

3.5. On business model innovation: a long primer

Over the years, the scope of creating CVP (customer value propositions) has extended from delivering basic products and services to crafting advanced BMs (Stonehouse and Snowdon 2007; Massa and Tucci 2014, Laszczuk et al. 2017). Porter (2001) netted this paradigmatic shift by declaring that a strategic fit among many activities is crucial, not only for a competitive advantage, but also for the sustainability of that advantage. Indeed, it would be stiffer, the author stated, for a competing company to match a collection of interlocked activities than to copy a specific sales force approach, match a technology process or duplicate a set of product features. And positions built on systems of activities, the author later on concluded, are far more sustainable than those built on individual activities.

Within this context, the old dictum of building a better mousetrap10 – as a means to make the world beat an innovation path to a company’s doorstep – springs to mind. Knowing that all companies (evidently!) have some sort of a BM, we, as a result, assume that the key questions that should be asked at this level are the following (Morris et al. 2006): Have the elements of the BM purposely been thought through following a customer-centric approach? Does a company decisively design all elements of the BM or does it focus most of its innovation on upgrading the core product? As put by Carassus (2004), all eggs are often put into one basket, that of product innovation, with the majority of companies constantly searching for differentiation through superior products while at the same time neglecting opportunities in other parts of the BM. Actually, to grasp the entire activity system is a complex task that frequently ensues in both overlooked areas and designs that are built on the dominant logic of the industry (Massa et al. 2017).

We carry on by asking: How could a company guarantee that its newly designed BM would end up delivering as planned? According to Christensen et al. (2006), four areas should be investigated for a company to establish a systematic overview of opportunities, exploit BM design and enhance customer value creation (Figure 3.10).

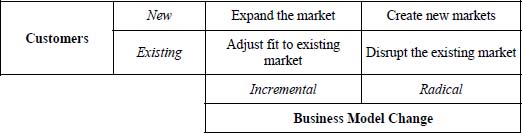

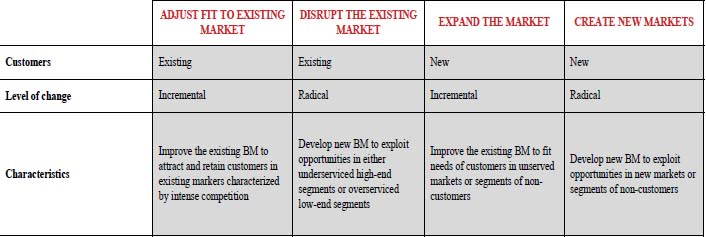

Figure 3.10. Typology of business model innovation opportunities

(source: created by the author – inspired by Christensen et al. (2006))

It is all about adjusting the current BM to exploit opportunities in existing markets. In fact, the shifting needs of existing customers and a turbulent environmental context constitute a window of opportunity for companies to amend their BMs (Chesbrough 2010). Under similar settings, simple incremental moves in some areas of the BM could be subjugated to achieve significant business goals. TDC (Tele Denmark Communications)11 is a great example of a company which, via the introduction of a free-music service layer, has vividly changed the stickiness of its BM, and diminished loss in market shares via improved customer loyalty and satisfaction. And so, as informed by Souto (2015) and Foss and Saebi (2017), changes brought to the table for the creation and design of new BMs do not necessarily always have to be radical – because simple moves, time and again, suffice to clutch new differentiation factors and accomplish great results in existing markets. But then, what about redesigning the current BM to expand the market?

Incremental change in the current BM may be leveraged to expand the market by attracting non-customers, thus converting latent demand into real demand (Lindgart et al. 2009; Koen et al. 2011). The practice of serving products in small, reasonable sizes is a broadly used strategy by global consumer brands to enter emerging markets. In the Philippines, for instance, 7 out of 10 smokers purchase their cigarettes by the stick rather than by the pack; also, 8 out of 10 Filipinos buy their shampoos by sachet rather than bottles (Rodolfo and Sy-Changco 2015). Here again, similarly to TDC’s case, the core product is left intact, while both innovative distribution setups and packaging designs became recipes for business success. So, now, how about tossing in a new BM that would disrupt the existing market? In some cases, inspecting the needs of current customers might lead to the discovery of attractive sub-segments which are not suitably served by the current BM (Kumaraswamy et al. 2018). Certainly, the detection of underserved or overserved customer segments could pave the way for important managerial decisions. This is chiefly the case of Nestlé’s Nespresso12 which, by eliminating the risk of failing to brew the perfect cup of coffee, and decreasing the time it takes to make a nice single-shot espresso, succeeded to identify and acquire an attractive niche of espresso drinkers (Söderberg 2019). In contrast to high-end disruptions typically achieved via notable technology leaps, low-end disruptions, on the contrary, are accomplished via simple cost-cutting measures (e.g. Ryanair).

Moving forward, we enquire: What about designing entirely new BMs? Schiavi and Behr (2018) precised that designing new BMs could be leveraged to create wholly new markets where large groups of customers have been, intentionally or unintentionally, locked out. Nevertheless, the authors added, in some specific cases, minor BM tweaks such as sachet marketing are just not enough. And so, a complete overhaul is required at times for a company to commercialize CVP for new markets. Table 3.6 shown below describes the growth opportunities that could be grasped through BMI. These opportunities, we say, could be explored and exploited by any company to sustain growth and delight customers. As per Markides (2013), introducing a better BM into an existing market is the definition of a disruptive innovation. Obviously, new BMs are not launched out of the blue, the author indicated, but rather closely aligned with overarching the strategic growth ambitions of the company. And so, the author added, a diagnosis of the strengths and weaknesses of current BMs must form the basis for any thoughtful attempt to pursue any generic growth opportunity.

To date, several scholars have suggested signs that could indicate that a company’s current BM is running out of gas. According to McGrath (2010) for instance, the first symptom is when innovation to a company’s current offerings create smaller and smaller improvements. In such as case, the author suggested, BMI is the only solution available. Similarly, Foss and Saebi (2017) affirmed that BMI is a crucial route for companies seeking to reinvigorate a lagging core, defend against industry disruption or decline, or even drive breakthrough growth. Amazon13 is a good example of a company that drove BM change in a resourceful way. At the start, the company was the Earth’s biggest bookstore; 20 years later, that bookstore turned into a leader in cloud computing, and started delivering groceries and producing Emmy Award-winning television series.

Table 3.6. Generic growth opportunities

(source: created by the author, inspired by Markides (2006, 2013))

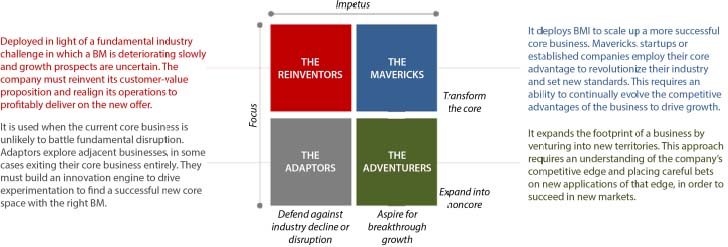

Figure 3.11. The four approaches to business model innovation

(source: inspired and adapted from Deimler and Kachaner (2020)). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/karam/general.zip

Unlike other types of innovation, changes to the BM infer changes to the foundational decisions upon which the business operates (Massa and Tucci 2014) – meaning that BMI is most likely to be radical and transformational. Changing the entire BM design (relative to incremental innovation: mere product innovation or technology enhancements) is possibly to be associated with higher risks, the authors said, with the possibility of disrupting the current business. Hence, “to find the right timing for a BM change is fundamental to business success”, they concluded. For well-established businesses, recognizing and managing this kind of radical change could be critical to their long-term survival, whereas for start-ups, such a change may be advantageous. With that said, although present-day changes in customer behavior, globalization and technological innovation have left the door wide open for the advent of new BMs (Schiavi and Behr 2018), we must realize that not all BMI efforts are alike (see Figure 3.11 for an illustration of the various approaches to BMI).

3.5.1. Definitions

To date, the BM concept has been embarked upon in the fields of innovation and technology management, with two chief ideas typifying the academic research pertaining to it: (1) companies promote original ideas and technologies via their BMs; and (2) the BM is a new substance of innovation by itself. Chesbrough and Rosenbloom (2002) advanced the case of Xerox to pinpoint the ability of a BM to unlock the value potential embedded in new technologies and convert it into a concrete outcome. From their side, Calia et al. (2007) affirmed that BMs could not only entail consequences for technological innovations, but could also be shaped by them. Moreover, as put by Johnson and Suskewicz (2009), BMs play a vital role in the commercialization of technologies at two levels, that of an individual company, and of an entire industry. In large, in infrastructural change, the authors argued, the key intent is to shift the focus from developing distinct technologies to creating completely new systems. The BM in such a case is introduced as part of an all-inclusive framework for thinking about systemic change. Although the BM looks like a terrific thing, we recap that studies on BM, innovation and technology management have shown that technology might not be enough by itself to guarantee business success (Doganova and Eyquem-Renault 2009), for it lacks inherent value (Chesbrough 2007).

Apart from embedding technology in outstanding products or services, Mitchell and Coles (2003) said that a company should design a unique BM to fully grasp its operating potential. Indeed, as per the authors, companies will possibly view the BM itself as a substance of innovation – hence, the notion of open innovation introduced by Chesbrough (2003). Generally, open innovation – being a mode of innovation in which companies look outside their boundaries in order to leverage internal and external sources of ideas – entails the espousal of new BMs designed for sharing or licensing technologies (Chesbrough 2010). Today, there is a swelling agreement that BMI is decisive of business performance (Foss and Saebi 2017), and the number of scholars investigating BMI as a means for corporate conversion and rejuvenation is on the rise (Johnson et al. 2008; Demil and Lecocq 2010).

At this point, now that we have concisely presented the concept of BMI, it seems opportune to define it. Overall, we proclaim, the definitions that we could come across while reviewing the academic literature on BMI diverge greatly, thus revealing some deep vagueness with regard to what the latter really is (Foss and Saebi 2017).

For some scholars, BMI is a process – while for some others, it is more of an outcome. Such variances, we proclaim, are expected to have significant implications for subsequent research on BMI. Indeed, studies that perceive BMI as a process often take a dynamic approach and look into the managerial physiognomies that facilitate or hinder the process of BMI (Demil and Lecocq 2010; Doz and Kosonen 2010), whereas studies focusing on the outcome tend to be more descriptive and identify the content of the BMI ex post (Bucherer et al. 2012; Günzel and Holm 2013). As put by Foss and Saebi (2017), even though both types of studies have their merits, they do deal with distinct phenomena, each requiring a different empirical approach to be scrutinized. Like for BMs, the definitions suggested for BMI are numerous (see Table 3.7), yet they tend to lack specificity. This, again, infers that there is no clarity in the literature about the nature of a BMI.

Table 3.7. Definitions of BMI

(source: adapted from Foss and Saebi (2017))

| Definitions | Author/s |

| BMI means BM replacements that provide product or service offerings to customers and end-users that were not previously available. The process of developing these novel replacements is also referred to as BMI. | Mitchel and Coles (2004) |

| BMI is the discovery of a fundamentally different BM in an existing business. | Markides (2006) |

| BMI is a reconfiguration of activities in the existing BM of a company that is new to the product service market in which it competes. | Santos et al. (2009) |

| Initiatives to create novel value by challenging existing industry specific BMs, roles and relations in certain geographical market areas. | Aspara et al. (2010) |

| BMI occurs when a company adopts a novel approach to commercializing its underlying assets. | Gambardella and McGahan (2010) |

| BMI is about generating new sources of profit by finding novel value proposition/value constellation combinations. | Yunus et al. (2010) |

| Innovate BMs by redefining: content (adding new activities), structure (linking activities differently), and governance (changing parties that do the activities). | Amit and Zott (2012) |

| BMI is the process that deliberately changes the core elements of a company and its business logic. | Bucherer et al. (2012) |

| A BMI happens when the company modifies or improves at least one of the value dimensions. | Abdelkafi et al. (2013) |

| Corporate BM transformation is defined as a change in the perceived logic of how value is created by the company, when it comes to the value-creating links among the company’s portfolio of businesses, from one point of time to another. | Aspara et al. (2013) |

| A BMI could be thought of as the introduction of a new BM aimed to create commercial value. | Berglund and Sandström (2013) |

| BMI refers to the search for new logics of the company and new ways to create and capture value for its stakeholders; it focuses primarily on finding new ways to generate revenues and define value propositions for customers, suppliers and partners. | Casadesus-Masanell and Zhu (2013) |

| BMI refers to (a) the design of novel BMs for newly formed companies (i.e. the activity of creating, implementing and validating a BM), or (b) the reconfiguration of existing BMs for established companies (the phenomenon by which executives reconfigure organizational resources and acquires new ones). Both phenomena are change phenomena and could lead to BMI. | Massa and Tucci (2014) |

| BMI activities could range from incremental changes in individual components of BMs, extension of the existing BM, introduction of parallel BMs, right through to disruption of the BM, which may potentially entail replacing the existing model with a fundamentally different one. | Khanagha et al. (2014) |

For the purpose of our research, we adopt the definition suggested by Pavie et al. (2013) for BMI. According to the authors, BMI is the art of enhancing advantage and value creation by making simultaneous, mutually supportive changes both to a company’s CVP, as well as to its underlying operating model. At the value proposition level, the authors affirmed, these changes could address the choice of the target segment, product and service offering, and revenue model. While, at the operating model level, they added, the focus is more on how to drive profitability, competitive advantage and value creation. Put differently, BMI describes a fundamental change (technology-driven or not) in how a company delivers value to its customers.

The next section exposes the four main streams of research on BMI.

3.5.2. Streams of research on BMI

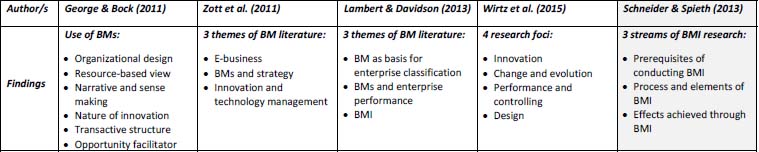

Although there is today a noteworthy number of studies that revise the existing literature on BMI (Zott et al. 2011; Lambert and Davidson 2013; Wirtz et al. 2015; Foss and Saebi 2017), there is only one that we believe to be complete and exhaustive – that written by Schneider and Spieth (2013), which appraises over 30 scientific papers on BMI. Foss and Saebi (2017), too, did a great job gathering and summarizing data linking to BMI research. Specifically, they reviewed nearly 150 publications in terms of their conceptual, theoretical, and empirical developments and contributions (Table 3.8), and distinguished four fairly overlapping streams of BMI research (Table 3.9). Those streams, the authors added, embody weighty evolutions, as well as limitations in the arena of BMI research in general. They are discussed as follows.

The first stream, conceptualizing BMI, centers on the phenomenon of BMI itself, suggesting definitions and conceptualizations of BMI (e.g. Teece 2010; Amit and Zott 2012). It also focuses on issues such as the least significant definition of BMI, and the dimensions along which companies could innovate their BMs (e.g. Santos et al. 2009). At this level, the purpose seems to revolve around the development of definitive, pictorial schemes; nevertheless, as formerly noted, most definitions available, though abundant, vary strikingly and are often unclear. When it comes to the second stream, BMI as an organizational change process, innovation is said to strongly defy prevalent managerial structures (Damanpour 1996). In contrast to the first stream, the second one goes farther by underscoring the competences, governance and scholastic systems required for prolific BMI. Indeed, studies carried out within the second stream define BMI as a vigorous process by: (1) recognizing the various stages of the BMI process (e.g. Gassman et al. 2014); (2) categorizing the different administrative know-hows and procedures needed to support such a change process (e.g. Demil and Lecocq 2010); (3) revealing the significance of research and knowledge (e.g. Andries and Debackere 2013); and (4) putting practical tools forward for the implementation of the process (e.g. Evans and Johnson 2013).

Table 3.8. Table 3.8. Streams of BMI research

(source: adapted from Foss and Saebi (2017)). For a color version of this table, see www.iste.co.uk/karam/general.zip

Table 3.9. Research on BMs and BMI

(source: Ibid)

Moving forward, the third stream, BMI as an outcome, embarks upon the yield of the second stream. Commonly, it addresses the advent of new BMs in a specific sector or industry (e.g. Schneider and Spieth 2013; Souto 2015). Also, some studies within this stream concentrate on scrutinizing a precise type of new BM – one that is conceived for low-income markets, for instance (e.g. Sánchez and Ricart 2010). Other publications within this stream (e.g. Matzler et al. 2013), we assert, tend to be descriptive rather than exploratory, limiting their contributions to commentaries on the creativity of some prominent companies’ BMs (e.g. Nestlé’s Nespresso). For some reason (one or more), the third stream does not build on the first one, yet, instead, the emphasis is put on unfolding one specific type of change in BMs – often said to be of a new kind. This stream is limited; it does not provide any discussion of the standards based on which the proper BM change could be seen as new.

Finally, the fourth stream, the managerial consequences of BMI, tackles the managerial performance repercussions of BMI. In this stream, we could distinguish between studies that link the BMI process to outcome implications (e.g. Cucculelli and Bettinelli 2015), and those that inspect the influence of various types of BMs on company performance (e.g. Zott and Amit 2008). In the first case, studies assume a process view and investigate whether an innovative change in the existing BM leads to larger performance outcomes (Giesen et al. 2007; Aspara et al. 2010; Cucculelli and Bettinelli 2015). In the second case however, studies do not directly link BMI to performance outcomes; instead, they test, following an empirical approach, the impact of various BM designs on innovation performance (Zott and Amit 2008; Wei et al. 2014).

To say the least, the BMI literature has so far yielded several key insights, allowing for a better understanding of the nature of BMI in general. One central contribution of BMI research links to the ability of companies to incorporate change in the design and architecture of their BMs as a strategic vehicle for the creation of both value and competitive advantage (Massa and Tucci 2014). Within the scope of our investigation, two lines of argumentation seem to be obvious; academic researches either follow a dynamic view of BMI or conceptualize it as a managerial change process (first stream), or view BMI as a new type of innovative schemes (third stream) that could ultimately influence business performance (fourth stream). We conclude by pointing out that the literature on BMI lacks academic works that plainly deal with the antecedents of BMI – yet, we note that the four research streams discussed earlier have largely evolved over time, perhaps disconnectedly, because no direct correlation could be spotted among them (Foss and Saebi 2017).

In connection with the present section, the next one demarcates the gaps in the academic literature on BMI.

3.5.3. Gaps and challenges

According to Foss and Saebi (2017), the existing literature on BMI is highly fragmented, and the gaps in the studies carried out over the years to investigate it are copious. For simplicity reasons, the identified gaps are categorized under six specific headers (themes), namely: (1) definitions; (2) dimensions; (3) antecedents; (4) outcomes; (5) variables; and (6) boundaries (see Table 3.10). They are clarified hereunder.

Definitions: up until now, we have plainly exposed the various inconsistencies in the definitions suggested for BMI, pointing altogether to a lack of clarity and specificity in the literature stream regarding the nature of BMI. Although this might not be a bad thing, a characteristic of a nascent research field that has not formed yet, such conjectural heterogeneity, we believe, may be challenging in the long run since research efforts would end up branching off in various, random directions14.

Dimensions: advances in research frequently occur when constructs are clearly dimensionalized, that is, when scholars succeed to capture the heterogeneity of a construct in terms of its key components that have relevant inferences for outcomes. Our review of the literature suggests that BMIs differ in terms of at least two dimensions: scope and novelty. The degree of novelty of BMI relates to whether BMIs are seen as novel at the company or industry level (e.g. Johnson et al. 2008; Santos et al. 2009). As for its scope, reflecting how much a BM is reflected by BMI, it could start small (BMI influencing only one component of a BM) (e.g. Amit and Zott 2012; Schneider and Spieth 2013), yet grow larger and larger over time (BMI influencing two components, three, four, or even all components of a BM – plus the architecture connecting them) (e.g. Yunus et al. 2010).