9

The female investor

When comparing those who identify as women and those who identify as men, in the stock market the average female investor makes more gains than men. They also lose less money than men. A 2021 Fidelity study analysed over 5 million investors and found that the women made 0.4 per cent better returns than the men. Now 0.4 per cent may not sound like a lot, but remember that beautiful concept of compound interest? These small gains compound over time.

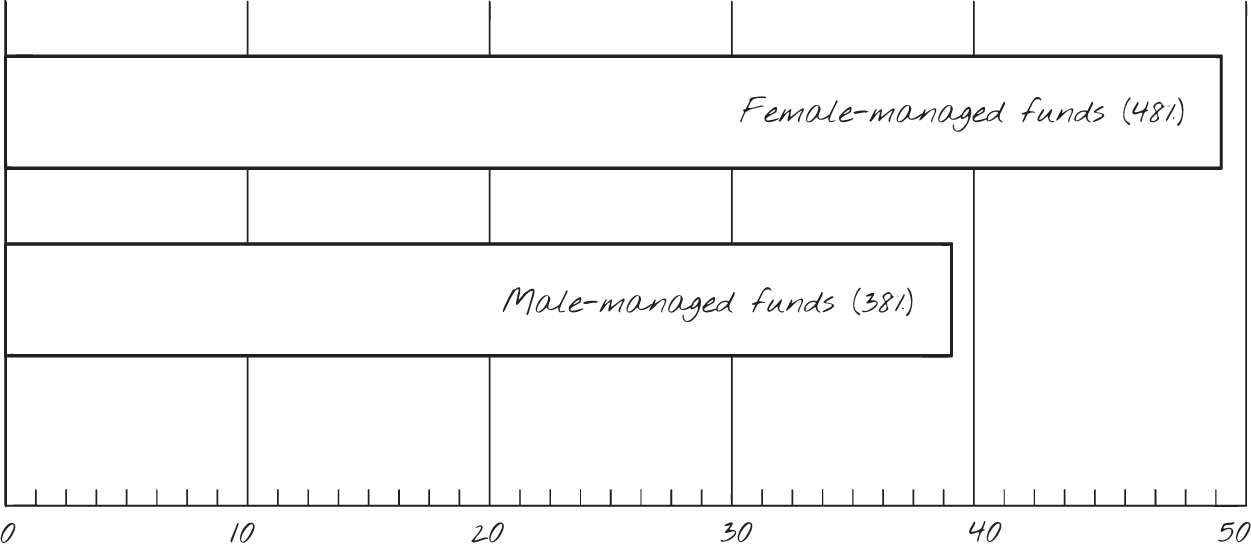

This is also seen in the professional sphere: a 2021 study by Goldman Sachs (reported by Forbes) found that 48 per cent of female‐managed hedge funds beat the market in 2020, while only 38 per cent of male‐managed funds did the same. See figure 9.1 (overleaf).

While we are better investors, only four in 10 women investors are comfortable with their investing knowledge.

We're better investors when we do invest, but in general don't feel comfortable to begin investing. What is the gap?

It's a lack of knowledge. Specifically, a knowledge of investing strategies. Understanding what a stock or a bond is may be one half of the equation, but what about the strategies used by everyday female investors that give them a leg up? What are they doing differently?

Figure 9.1: percentage of fund managers beating the market in 2021

Source: Based on data from a study by Goldman Sachs. Reported by Jacob Wolinsky. Here Is Why Female Hedge Fund Managers Outperform Men. 31 July 2021. Forbes

A lot of research has been done into this. In this chapter I'll get into the findings of that research, discussing the investing strategies women tend to use.

Women are told we’re risk averse, but we’re not. We’re just risk aware.

Once we understand the risk and strategies involved in the world of investing, we're happy to dive in — we just need that foundational knowledge to begin with. If we know why we're better when we invest, we can start out on the right foot and have confidence that we're making the best decisions as investors in training.

One surprising thing is that many of these ‘female‐led’ strategies are basically how the famous investor Warren Buffett invests. When Buffett was asked if he invested ‘like a girl’, Buffett replied: ‘I plead guilty.’

Let's go through the seven investing strategies that have made female investors outperform their male counterparts consistently. This is how you ‘invest like a girl’:

- passively invest

- dollar cost average

- emotions and the market

- don't fall for FOMO

- check your portfolios less

- invest for the long term

- invest in what you understand.

#1: Passively invest

You can try active investing: investing in individual stocks, where you try and pick companies that will beat the market. Or you can just invest in the market itself through a passive index fund. Female investors in general have shown a preference for the passive investing strategy. Let me tell you a secret: I know a female Wall Street trader who, while she actively trades professionally for her job, only personally invests in index funds. There are no stocks in individual companies in her personal portfolio. She knows trying to pick stocks is not worth her time, despite doing it for her full‐time job.

We prefer to invest for the greatest gains with the minimum effort and involvement possible, which is where passive investing through index funds fits in perfectly.

With passive investing into index funds or ETFs, you end up diversifying your portfolio naturally as well. If you have even one share of the S&P 500, you're now a shareholder in 500 companies across a multitude of sectors in the US. By diversifying your risk, you're able to ride out the fluctuations in the market as well. For example, during the COVID‐19 pandemic airline stocks dropped, but it wouldn't have mattered if you also had Zoom stocks, which went up. The even better part is that passive investors didn't have to rush to buy and sell once those Zoom or Microsoft shares started to soar; it was all adjusted automatically for them through their fund. That is the beauty of passive investing.

This is one of the few ‘female’ strategies that Warren Buffett doesn't use. Buffett is an active value investor; he tries to actively pick stocks that he thinks are undervalued. Basically, he's looking for Tatcha skincare at Nivea prices.

However, despite being an active investor, Warren Buffett is a huge advocate for the average person investing in index funds rather than trading. In fact, he believes that for everyday investors, active investing will only lead to ‘worse than average results’. (Remember chapter 5 where I talked about his bet with a hedge fund that a passive index would beat the actively managed hedge fund's performance over 10 years?) When it comes to his family, he wants 90 per cent of his estate invested into index funds, specifically the S&P 500, when he passes away.

When you focus on passive investing you’re looking at all the research that is stacked against you in terms of trying to pick winning stocks. Studies like those by the Research Affiliates in 2013 have found monkeys perform better in picking random stocks than investors. I can’t say I’m any better at picking stocks than those monkeys.

#2: Dollar cost average instead of trying to time the market

Many people save up their first lump sum to invest and can't decide if they should put it all in at once or slowly over time. Should you wait for the market to drop?

Investors in training know that there is no point trying to time the market. If someone could perfectly time when the markets dropped and peaked, they would have become millionaires by now with their ability to always buy stocks at the bottom of the market and sell them when they knew the market was at its highest. But the reality is, you only know the bottom and the peak once they're gone, and by then it's too late.

Investors in training tend to know it's futile to try timing the market and instead use the strategy of dollar cost averaging. Let me explain this further.

How dollar cost averaging works

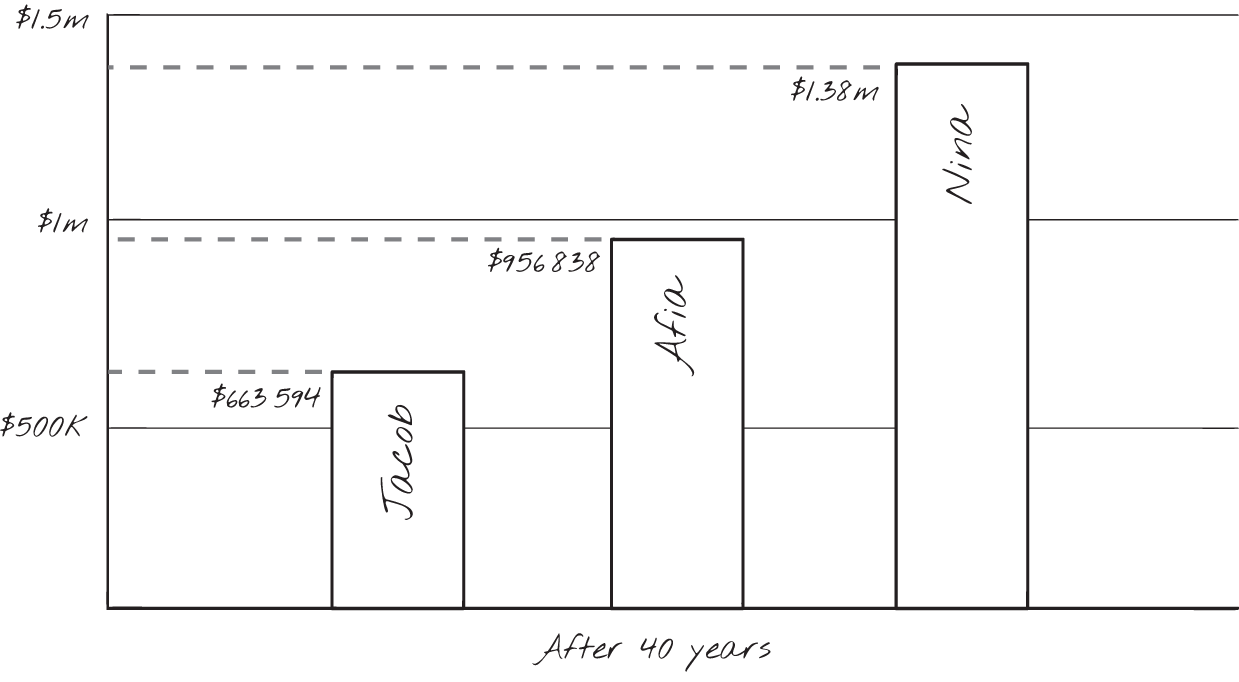

Imagine three friends. The first friend, Jacob, decided he wanted to save $200 a month and keep it in a high‐yield savings account with a 3 per cent interest rate, saving it up to invest when the market drops. Let's say Jacob has been doing this over the last 40 years and ends up having the world's worst timing. In fact, he invests the day before all of the four big crashes, meaning he makes an immediate loss the day after he puts his money in … four times. Poor Jacob.

But let's say Jacob has some sense in him, and he doesn't panic‐sell and instead holds on to his investments. By the end of the 40‐year period he'll have made $663 594.

Then there's Afia. Afia is like Jacob and wants to time the market. She also saves $200 a month and keeps it in a high‐yield (3 per cent) savings account. She ends up having the best timing in the market and somehow ends up investing in the lowest point of the four biggest crashes.

Afia ends up with a portfolio worth $956 838.

Now there is a third friend, Nina. She decides to not worry about timing the market and simply invests $200 every month into the same fund, through all the highs and lows.

Nina ends up with $1.38 million at the end of 40 years. How? It's the beauty of dollar cost averaging: that you ride out the highs and lows of the market, and you reap the rewards of compound interest. See figure 9.2 (overleaf) for a graph of all three different investment approaches.

Figure 9.2: Jacob's, Afia's and Nina's investments

Some days you'll invest in the funds when they're a bit higher, some days you'll invest in funds when they're slightly lower, but by averaging out your chances of investing at a ‘good price’, you end up doing better in the long term.

The thing with the stock market is that a lot of big gains in the market can be concentrated in a few days; the market doesn't go up the same percentage every day. The Bank of America analysed data from over 91 years, all the way back to 1930, and found that there were only 10 days each decade that made a huge difference to an investor's portfolio. In fact, if an investor had missed out on the S&P 500's 10 best days each decade, their total return would be 28 per cent lower. But if they bought and held their investments through the ups and downs instead of trying to time the market, their return over the 91 years would have been around 15 000 per cent. They also found that some of the best days in the market actually follow big drops, as seen in the COVID‐19 crash, where stocks rallied (a jargon term which means ‘rose upwards’) significantly.

No‐one can time the market. Investors in training dollar cost average and keep some cash, perhaps $1000 to $2000, aside just in case they see a drop and want to add extra money into their fund. But that's their extent of ‘trying to time the market’.

Time is money, and investors in training would rather spend their time enjoying their lives and having meaningful experiences than hunching over a screen daily trying to work out the next drop. After all, aren't we investing for more freedom of time?

You can dollar cost average every week, fortnight or month. If you are unsure which timeframe is better, the rule of thumb is that the more money you have to invest the more often you can invest to counteract the brokerage fees you might face at each investment. Investing $10 a week with a $2 fee may not be wise, but investing $500 a week for a $2 fee suddenly isn't so bad.

Another downside of trying to time the market is that sometimes people get so much analysis paralysis they miss out on the market completely.

You don't want to be the person who keeps waiting for the best time to invest and ends up never investing at all.

#3: Emotions and the market

One of our top traits is that we have good emotional control when the markets fluctuate. (A bit ironic since we've always been told that we're an overly emotional gender and any bad mood is due to probably being ‘on our periods’. I guess our investing portfolios say otherwise.)

You know those stock photos of men with their heads in their hands during stock market news? You do not want to react like those men during volatile times in the market, because you know as an investor in training that volatility is to be expected and that you're investing for the long term. Bet they feel really silly now.

When emotions take over our strategy, investors tend to elevate risks that they could otherwise avoid. This is not exactly brand‐new information; we all know you don't make the best decisions when your judgement is clouded by emotions.

Having emotional discipline during a bear market isn't easy for anyone. It takes guts to look at your stocks ‘all in red’ and not want to panic and pull your money out. Remember, if you have 10 shares, even if they're in the red, you still have 10 shares. The number of shares you have during a market downturn hasn't changed, it's just the value of them that's changed, and, if you invest in a diversified low‐cost broad market fund, you should eventually see the value rise back up.

Instead, when the market drops, investors in training with good emotional control see it as an opportunity to buy more stocks they love — it's a sale day for your favourite stocks and funds. Like seeing that MacBook you wanted, but it's now $999 instead of $1999. (It's important to note that you don't want to just buy any falling stocks during market drops. How many times have you regretted impulse buying something you didn't need just because it was a ‘good deal’?)

The other side of the emotional coin is being overconfident when the stock market is doing well. There's a saying in the investing world that a rising tide lifts all boats. When the market itself is doing well, like what we experienced in late 2020 to late 2021, you could take a punt at a few companies and see them rise in value. Investors in training know not to mistake good luck or good timing as skill. They also know not to over‐invest in a recent winner. If their Microsoft stock went up 200 per cent, it doesn't mean they should necessarily invest more money into it. It's still important to stick to the fundamentals of analysing the company's future growth. One of the worst mistakes an investor in training can make is selling what has done poorly and putting more money into what has done well. (That's buying high and selling low, the opposite of what you're supposed to do!)

One of Warren Buffett's famous quotes is to be greedy when others are fearful and fearful when others are greedy. He's essentially saying to invest in the opposite way from what your emotions are telling you. It's not an easy skill to learn, but investors in training will be rewarded for their ability to strengthen their emotional discipline.

#4: Don't fall for FOMO — stick to a strategy

Fear of missing out (or FOMO) investing is when investors feel pressured to invest in a company or fund because they are scared they'll miss out on a big opportunity.

No‐one wants to be left behind in a gold rush. No‐one wants to be the person who laughed at Bill Gates when he shared his views about how the internet would change the world. Everyone wants to find the next Apple: stocks that skyrocket after their IPO and make many people wealthy.

However, for every Apple there are hundreds of stocks that don't make it. After all, small‐cap stocks, smaller companies looking to grow quickly, are often more volatile.

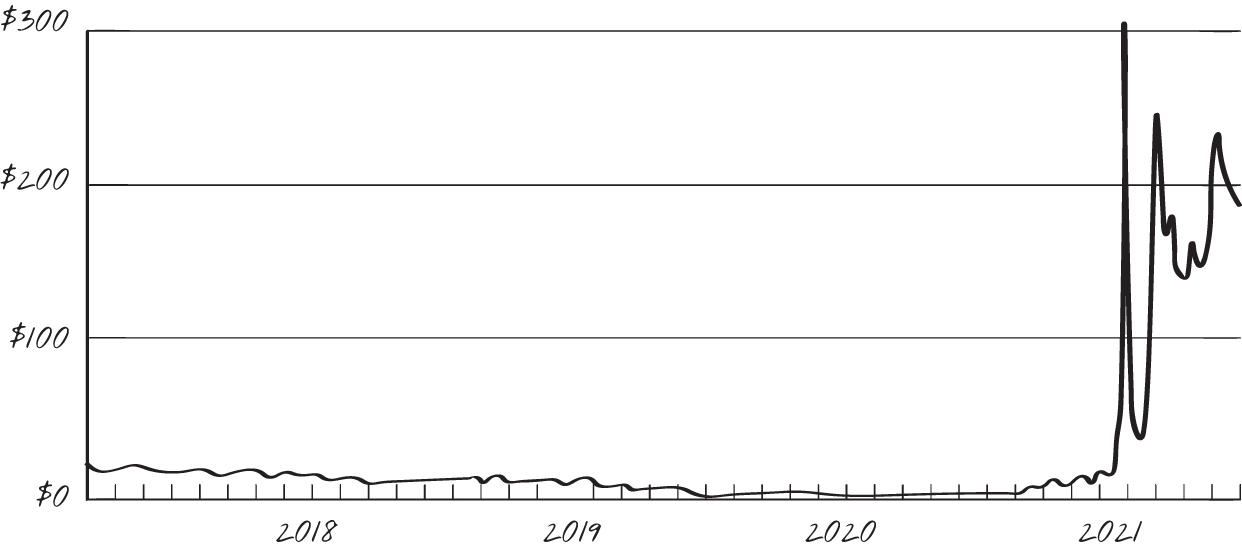

Now that it's easier and faster to access information than ever before, FOMO investing is harder to resist, especially with the likes of GameStop or AMC skyrocketing in 2021. GameStop was a videogame and merchandise retailer that was on a downward trend. Yet, due to FOMO investing and a concerted effort by investors on Reddit's r/wallstreetbets forum to ‘stick it to the man’ the stock went from US$17.69 on 8 January 2021 to US$325 on 29 January … and then down to US$40.59 on 19 February (see figure 9.3, overleaf).

Seeing friends and family have success with a particular stock can provide investors with an overly heightened sense of confidence about the investment.

Figure 9.3: GameStop's wild ride

Source: Based on data source from GameStop ‐ Stock Price History | GME. Macrotrends LLC.

A recent New Zealand study by the Financial Markets Authority (FMA) found 31 per cent of investors in 2020 and 2021 had bought stocks on the basis of FOMO, and that 27 per cent invested based on a recommendation from someone they know, without doing their own research. They didn't want to miss out and jumped on the investment. The FMA were alarmed to say the least, and started a country‐wide campaign to educate investors about the dangers of FOMO investing.

Female investors are less likely to succumb to peer pressure in investing and are more likely to hold on to their investing strategy.

They realise the importance of blocking out the noise and sticking to their strategy of dollar cost averaging into their index funds, and keeping speculative investing, like with FOMO stocks, to a bare minimum.

This is not to say female investors do not engage with FOMO investing. The study found that of their sample speculative investors, those who were strongly influenced by FOMO investing, 66 per cent were males and 35 per cent were women.

It would be unrealistic to think that investors aren't going to be tempted by FOMO investing throughout their entire investing journey, so if you are going to do it, only put in what you are comfortable with losing. Investors in training know that they should keep any speculative stocks as a small percentage of their portfolio — ideally less than 5 per cent.

One investor, gender unknown, from the study stated ‘how tempted I was to jump on the bandwagon, as a lot of my friends did. But the result’ (once the FOMO stock dropped) ‘just reiterated to me how I’m only here to play the long game, and these short sharp rises are synonymous with lottery winnings'.

As the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in the US warned in 2017, ‘it is never a good idea to make an investment decision just because someone says a product or service is a good investment’. Say less, SEC.

#5: Check your portfolios less frequently

Female investors spend more time researching stock picks, but once we do, we don't check them as often. Nearly half of investors check their stock performance at least once a day, and that's worrying. You do not want to be checking your portfolio too often.

Why? As we've learned from money psychology, we hate losing money more than we love making money. We're more upset if we lose a $100 note than we are excited when we find a $100 note. Even though the value we lose or gain is the same, the emotional output differs a lot. We feel the pain of loss about two times more intensely than we feel the pleasure of gain. It's a concept called loss aversion, discussed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in their 1984 study ‘Choices, Values, and Frames’, then later in Kahneman's book Thinking, Fast and Slow.

The relationship between how often you check your portfolio and how much money you make is documented well; the more often you check your portfolio, the more likely you are to see a loss.

An investor who checks their stocks more often, for example daily instead of quarterly, has an increased risk of losing more money, Kahneman observed. You're more likely to act on what you see.

This is one of the key strategies to having a successful investing portfolio. How often should one check their portfolio? Technically, as little as possible. Investors in training usually check their portfolio once every month to once every quarter. If you're currently checking daily, start off with monthly to get into the habit of checking it less, and then eventually move this to quarterly.

This doesn't mean only invest once a month or once a quarter, but have automatic systems set up that invest for you, so that you don't have to check your stocks as often.

Investing information has never been more accessible, but that doesn't mean investors should constantly access it. Female investors are able to control this urge to stay updated on the small movements of their portfolios and end up being better off for it.

#6: Invest for the long term; don't trade as often

Female investors increase their earnings by trading (i.e. buying and selling) less frequently. Men are 35 per cent more likely to trade stocks than women.

During periods when there is a lot of volatility in the world, such as during presidential elections, ebola outbreaks or a debt crisis, the number of trades on platforms increase — however, women continue to trade less frequently than men.

Even more recently, during the 2020 COVID‐19 pandemic, women traded less during the market turmoil than men, leaving them better off in the long term. Nutmeg, an investing broker, found that during the start of the pandemic in March 2020, men were twice as likely than women to withdraw money during the downturn of the market, solidifying their losses. Whereas 95 per cent of women made no adjustments to their portfolio.

There's a popular phrase in the world of investing called ‘buy and hold’, and it's popular for a reason.

Female investors tend to invest for the long term and don't change their investing strategy easily. It's easy to get affected by the hype of FOMO or fear when the market drops, as mentioned earlier. But investors in training know that, on average, the stock market returns 7 to 10 per cent, and if anything is suggesting a guaranteed return of more than this, it is unlikely to be true. They are also aware that if they have a solid investing strategy that includes diversifying in broad market funds, buying and holding and checking their portfolios less frequently, there's less to worry about. It goes back to the idea of starting out with a solid foundation based on knowledge and research. Investors in training know that a house will crumble if it doesn't start out with good foundations.

When it comes to marital status, the pattern is still the same: according to a Wells Fargo report in 2019 ‘Women & Investing’, single women trade 27 per cent less frequently than single men. Interestingly enough, men's trading activities quieten down when they begin sharing finances with a female partner.

This tendency to buy and hold could be attributed to female investors being more risk aware, and therefore deciding to engage in further research before investing. Female investors are also more likely to seek financial help (a bit like the stereotype of women being more likely to ask for directions when lost) if they have queries.

A study led by the Haas School of Business and UC Davis Graduate School of Management found male investors tend to be more overconfident in their investments, which leads to more frequent trading, and therefore lower returns.

Investors in training, regardless of what gender they identify with, can learn from these behaviours and understand the importance of trading less frequently and seeking advice if they are unsure.

#7: Invest in what you understand and ignore the rest

The final strategy that female investors employ is being honest with themselves and only investing in what they understand. This is not to say male investors understand more — but if both groups are equally ignorant about a new investment class, male investors are still more willing to try it out than female investors.

For example, female investors will invest in assets such as cryptocurrencies, but on a lower scale and keep it to a smaller percentage of their overall portfolio.

It's a concept that Warren Buffett himself employs; he openly admits that he doesn't invest in many tech companies because he does not understand them. While this may have kept him out of some big gains from tech booms, it has also protected him from the Dotcom Bubble in the early 2000s (mentioned in chapter 2), where people were investing in any company with ‘.com’ in its name.

Five rules of investing like a girl

When researching companies to invest in, there are five rules to employ to help you invest ‘like a girl’ (or like Warren Buffett), as outlined in table 9.1.

Table 9.1: Five rules of investing like a girl

| Rule | Reasoning | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Company has a moat | This makes sure that the company is well known or has a patent that stops competitors from trying to take its business | Coca‐Cola |

| Company invests in research | More important for younger investors; you want a company that is continuing to innovate and grow | Pfizer |

| Company has good leadership | A company that has good leadership is more likely to have a trickle‐down effect on the growth of the company and how it handles downfalls | Alphabet (Google) |

| Company is adaptable | Companies that respond well to change don't get left behind, like Nokia during the smart phone revolution | Apple |

| Company has a growing bottom line | A company that has an increase in revenue isn't very helpful if their net income or bottom line isn't growing as well | Microsoft |

***

The strategies employed by these investors show an investor who is calm, collected and confident in their stance. They don't trade as often, don't check their portfolio as often and don't waiver under pressure to join the hype.

It is easy to be swayed by the news but an investor in training is sure in themselves and agile enough to ask for help when they need it.