10

The lazy investor

By now you understand the difference between active and passive investors. Active investors are trying to beat the market average by choosing stocks, putting time and energy into reading company financial statements, skimming through balance sheets, looking at a company's assets and debt and reviewing how the company controls its cash flow.

Some active investors can beat the market in the short term but this gets harder as time goes on, and for long‐term investors — those who are investing for 10‐plus years — they're better off taking the passive approach, or at least keeping some of their portfolio in a passive strategy. In this chapter we'll get into the lazy (i.e. passive) investor strategy, but first, let's look into how active investors do what they do.

Active investors

Active investing can be broken down into two approaches: fundamental analysis and technical analysis.

Fundamental analysis

Fundamental analysis is the practice of trying to work out the intrinsic value of a stock because you believe the intrinsic value is different to its actual value. You look at the book value of companies and analyse tables to see if it's worth your time. It's the process Warren Buffett uses to determine if he will invest in a company or not.

My mum practises fundamental analysis when we travel to India by only paying what she believes something is worth at markets. In the process of haggling, if she believes something is worth 100 rupees and the shopkeeper is trying to sell it for 150, she'll walk away. She doesn't see the price of an item and assume the price equals its value.

Meanwhile, my father would just pay the 150 rupees. He believes the cost of an item is already reflected in the price. This is what passive investors do. They do not believe the intrinsic value of a stock or fund is separate, they believe all factors that could affect the stock have been ‘priced in’ to the stock price.

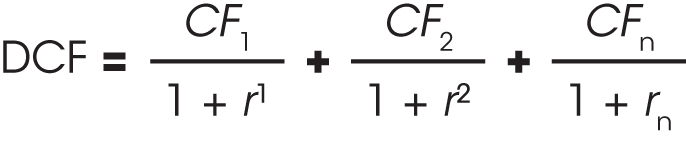

There are many ways to find out the ‘intrinsic value’ and compare it to its current price. The discounted cash flow method (DCF) is the most popular. It tries to work out the value based on projections of how much the company will generate in the future.

The calculation for this is:

where:

- CF is the cash flow for the given year

- CF1 is for year one

- CF2 is for year two

- CFn is for additional years

- r is for the discount rate.

However, it's much easier to plug this into any online calculator.

Active investors believe that, sometimes, if a company's price drops (e.g. after bad news) it's only a temporary drop and therefore they can purchase the stock on sale. Let's say you want to invest in Boeing after some bad news about the company came out, and you believe that it has temporarily dropped in price.

The stock price is $200 but the DCF method shows you the intrinsic value is $210. This means you've found a company on ‘sale’ so you purchase it, knowing you've scored yourself a bargain.

Technical analysis

Technical analysis, on the other hand, takes an active investing strategy that looks at graphs rather than tables, and also, like a passive investor, assumes the stock price has been priced in; that is, that the value of the stock is equal to its price. They believe that history can be used to assess how stocks perform and people (and therefore the supply and demand of the market) behave. They believe you can use patterns to determine what the next move is.

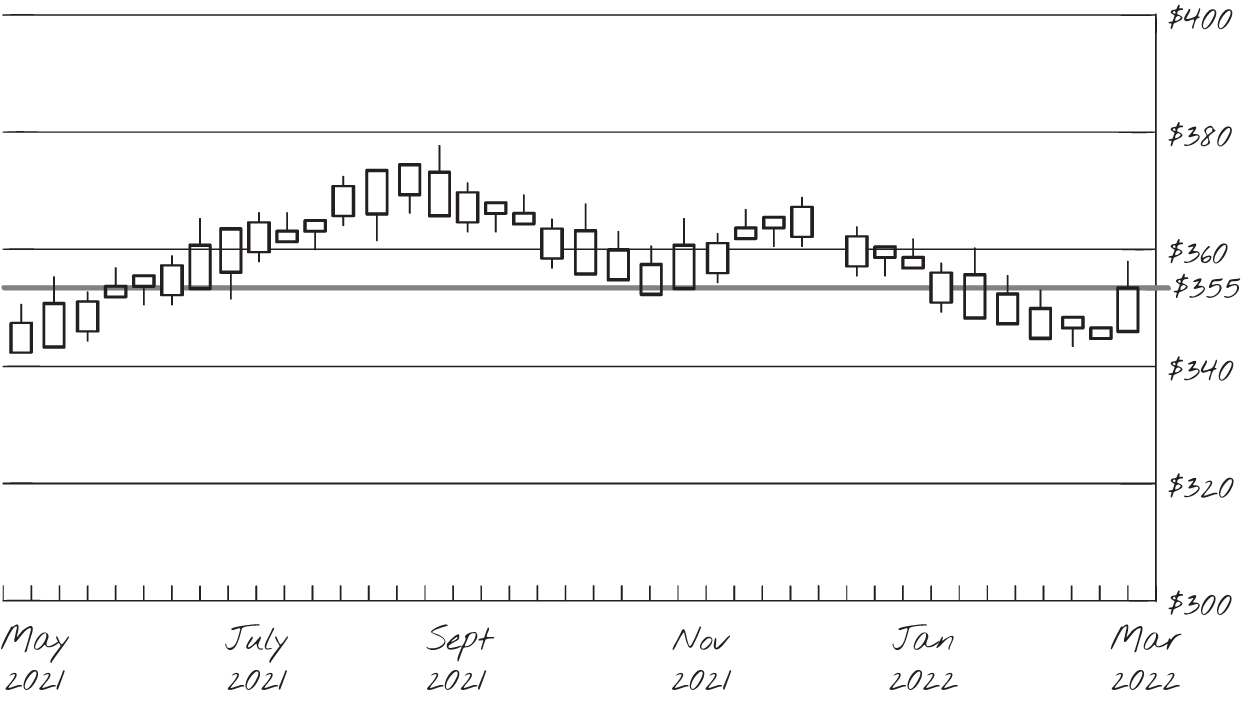

These are the types of investors you've always been intimidated by, the ones with ‘candle stick charts’ (see figure 10.1, overleaf).

There are hundreds of patterns that technical analysts use to forecast how a stock will move, including trendlines, channels and momentum indicators. Critics believe that technical analysis only works at times and that history doesn't repeat itself. It can also be a bit of a self‐fulfilling prophecy; for example, when technical analysis ‘predicts’ correctly, then credit may be given to the strategy, but if it doesn't go to plan, the blame may be given to the analyst who ‘just understood it wrong’.

Figure 10.1: a candle stick chart

The lazy investor

The data seems to back the critics of active investing. Between 2004 and 2014, Morningstar compared over 500 actively managed funds in the US with passively managed funds. The active funds returned 8.05 per cent and the passive funds returned 9.27 per cent. Investors in training don't see the benefit of greater work for lower outcomes, and thus the lazy investor was born.

Before we begin, the term ‘lazy investor’ is not a dig at this strategy. It's just referring to how easy it is to use. The lazy investor, or three fund portfolio, is an investing strategy coined by John Bogle, the guy who invented index funds. Those who are huge fans of the method are self‐proclaimed ‘Bogleheads’.

In the personal finance community this investing portfolio is regarded as the gold standard of how to allocate assets if investors in training are unsure of where to begin. It's an easy‐to‐understand and popular risk management tool.

Index funds or ETFs (remember the baskets that invest into a list like the S&P 500 or the FTSE 100) are an integral part of the lazy investor strategy. It works by holding a total of three ETFs.

I like to think of it as picking a group of friends; each fund represents a type of person you want in your friendship group. You adjust the percentage of each friend type you'd prefer to suit your personal needs, and this is going to change over time. The people you like to hang out with at 15 aren't always the people you want to have at 20 or 30 as you grow and develop.

The three funds that a lazy portfolio has are:

- a broad US market index ETF

- a broad international market index ETF

- a bond ETF.

Why a broad US market index fund?

This is funds such as the Vanguard 500 Index Fund ETF (VOO) or Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund ETF (VTI). They allow investors to have access to either the top 500 companies in the US or the entire US stock market respectively.

Why the US market? It holds some of the world's largest companies, holding 55.9 per cent of the market share of the total world equity market. You can replace this with the index in your home country such as the FTSE 100 in the UK, the ASX 200 in Australia or the NIFTY 100 in India. But with the US market, you get more exposure to some of the biggest brands on the planet. It's like having a friend that's a big shot — they're popular and they're not too risky to be around, but sometimes they do get overly confident so they aren't entirely free of risk.

Why a broad international market index?

An example of one of these is the Vanguard Total World Stock Index Fund ETF. This is your worldly friend. They open you up to international experiences. This fund has over 7000 stocks from 47 countries. It invests in both foreign and US stocks by tracking the FTSE Global All Cap Index, which covers countries from both developed and emerging markets. The US accounts for 59 per cent of this fund followed by countries like Japan, UK, China, Canada, France, Switzerland and Germany, which make up the rest.

The benefit of this ETF is that you are invested in every sector in every part of the world. The diversification is strong.

It's important to note that this friend is slightly more volatile due to their jet‐setting ways; they might get stuck somewhere due to a railway strike or regime change.

Emerging markets aren't as stable as the US market, but that doesn't mean they shouldn't be a part of the gang.

Why a bond ETF?

If stocks are the risk‐taking, more extroverted friends, then bonds are the introverts. And in every group of friends you need the loud to be balanced out with the quiet — trust me.

A bond ETF such as the Vanguard Total Bond Market Index Fund ETF is an option to consider. It tracks the Bloomberg Aggregate Float‐Adjusted Bond Index. The benefit of having bonds in your portfolio is that it reduces risk, even if it comes with a slightly lower reward. You're able to have a bit more diversification in the market. When you're hungover and have lost your wallet, stranded somewhere after a big night out with the extroverts, the bond ETF is there to pick you up and give you a cup of tea.

They're the friends you don't really realise you need until things turn to poop.

Why have all the examples been Vanguard related?

Vanguard host the lowest fees. A lot of passive funds are very similar, and often invest in the exact same things. That only leaves one feature to compare, and that's fees. By all means feel free to invest in other branded ETFs — you'll get the same returns, the fees will just be different.

How to balance your friend group

So what per cent of each fund do you need in your portfolio? Let's work it out.

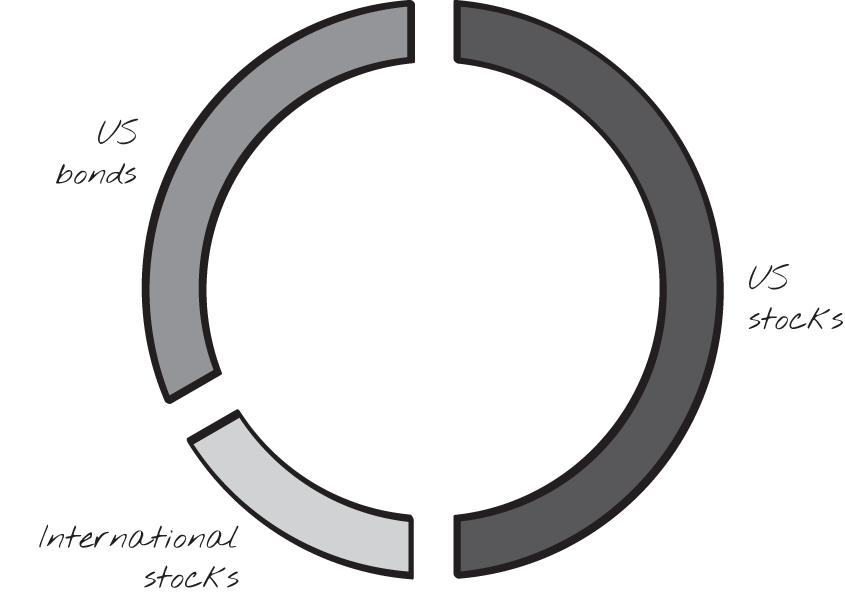

This is going to be different for each person, but a rule of thumb is that the riskier you are willing to be, the more stocks, like the US and international index funds, you're going to have in your portfolio, with a lower percentage of bonds (see figure 10.2).

Figure 10.2: riskier lazy investor

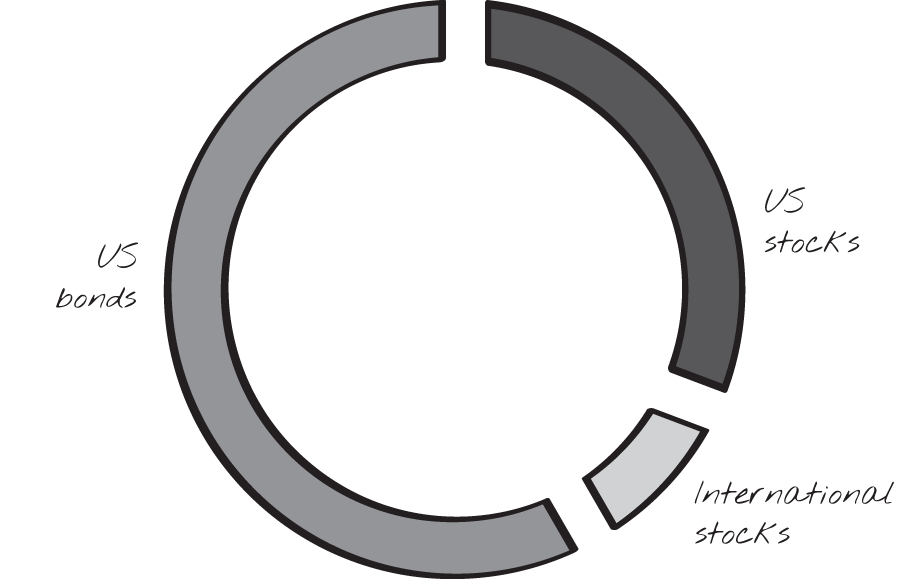

Someone who doesn't want any friendship drama, and instead wants less risk for less reward, would consider a portfolio that is more bond heavy (see figure 10.3).

Figure 10.3: less risky lazy investor

But how do you decide what your risk profile is? Think about two things:

- how old you are

- how long you want to invest for.

A rough way to work this out as a lazy investor is to take the decade of your age and subtract it from 100. This is how much should go towards stocks.

So, for example, at 25 years old, 100 – 20 = 80. This person's portfolio should be 80 per cent stocks and 20 per cent bonds.

But for someone who is 45, 100 – 40 = 60; their portfolio may be 60 per cent stocks and 40 per cent bonds.

How long you are investing for is also important. Someone who is investing to buy a home in five years probably is better off being more bond heavy, whereas someone who is investing for 20 years to retire early could get away with more stocks than bonds, as they have more room to ride out the waves. You can also take the quiz in ‘Putting it all together’ to work out your personal risk profile.

So why the three fund method?

The advantages of this approach are:

- it's an easy set‐and‐forget method

- you can adjust your risk level

- it offers high diversification for low fees.

It's an easy set‐and‐forget method

The lazy investor portfolio is a great way to begin without having to do a lot of research and spend a lot of time going through data. Rather than trying to beat the market, John Bogle believed in being the market. If you can't beat 'em, join 'em.

If you automate your finances so that X amount of your pay cheque goes into an account, and every month a set dollar amount goes into your online brokerage account, which splits your money across these three investment funds, you have created an automatic system that you do not need to check. You do not need to worry about timing the market or missing out on good deals. It is truly a set‐and‐forget method.

You can adjust your risk level

One of the best parts about this method is the ability to adjust it against horizon risk, which you may remember is the risk that you have a change in your life and suddenly need to adjust your strategy.

If I need my money sooner, let me invest into more bonds.

If I decide I don't want to buy a home anymore and this money is going to be my retirement fund? Let me buy more stocks.

The ease of changing your position without buying and selling hundreds of stocks is one of the beauties of the lazy investor method.

It offers high diversification for low fees

Many online brokerages charge a fee for every company you invest in. This can usually range from a few cents up to $15 if you're unlucky. If you were gaining access to 7500 companies by investing in each of them on their own, your brokerage would have a champagne party using the money from your brokerage fees alone.

By investing in funds, you lower the fees you must pay for the number of companies you are exposed to. Index funds and ETFs also have lower fees in general, with Vanguard ETF fees being as low as 0.03 or 0.04 per cent at times.

Downsides to the lazy investor

That's not to say there aren't a few downsides to the lazy investor strategy: you can't tailor your investments to your ethics, and you're only getting average returns.

Can't always be ethical

With the lazy investor method you are investing in a wide range of companies across the world, which also means being exposed to certain companies you might prefer to avoid, such as Johnson & Johnson or Nestlé. Some investors in training are okay with these companies receiving such a small percentage of their asset allocation, but some investors may not be as comfortable.

It is entirely possible to swap out ETFs in your lazy portfolio for ones that align with your ethics, but also make sure they have a broad range of companies in them. For example, an ETF with 100 companies is better in terms of diversification than one with only 30.

You're getting average returns

If you make simple portfolio choices that invest in the market instead of trying to beat the market, you're spending less time worrying. But this also means you're just getting average returns.

For some people, being average isn't enough. The investor in training understands a 7 to 10 per cent annual return over the long term is a good average to aim for, but they may be enticed by other investors who make 20 or even 30 per cent returns in the short term through stock selection.

***

The most important thing is for investors in training to be comfortable with their investing strategy and to stick to it. It is easy to be swayed, and to question what you are doing when you see other investors behave in reaction to the market, but not everything that glitters is gold.