Chapter 5. Technology’s Influence: Past, Present, and Future

At this point, you may be thinking that technology has caused more harm than good. Granted, some of these glitches do read like a spy thriller or the makings of a cineplex blockbuster, but it’s not all doom and gloom. After all, technology is the reason why we have electric power, clean water, public transportation, and so on.

There’s no denying that the IT sector has been an engine for wealth creation and will continue to fuel the global economy for the foreseeable future. However, being able to maximize the rewards from this industry is not a given. It will require a closer look at where we are, where we’ve been, and what can potentially hold us back from where we want to go.

This chapter explores the following topics:

• Technology as an economic growth engine

• A brief history of the technology industry

• The impact of the Great Recession

• Critical success factors for the future

Technology as an Economic Growth Engine

Aside from some very public ups and downs, most notably the dotcom collapse, the information technology sector has consistently been a source of job creation and a contributor to the global economy. Looking at some facts and figures over the years, as well as future projections, we can expect this trend to continue.

A recent report from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics found that employment of computer software engineers is projected to increase by 21 percent from 2008 to 2018, which is much faster than the average for all occupations and represents 295,000 new jobs.1

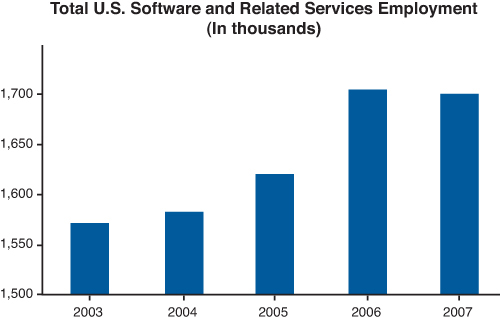

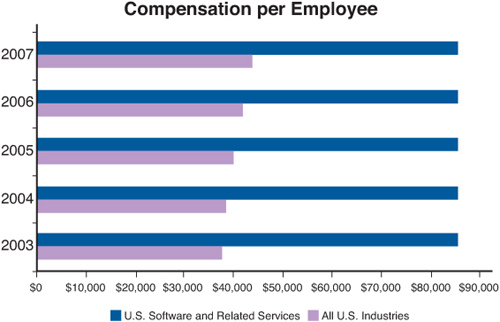

Along with increased job opportunities, IT-related salaries have steadily risen through the years. These numbers go beyond the standard cost-of-living increase or inflation. Consider that, in 1985, the software and related services sector in the United States employed 637,400 people, with an average annual salary of $30,031.2 By 2007, that number had risen to 1.7 million people earning $85,600 annually, representing 195 percent of the national average.3 Figure 5.1 illustrates total software and related services employment. Figure 5.2 shows the steady income growth of professionals in the U.S. software and services industry.4

Figure 5.1 Total U.S. software and related services employment

Figure 5.2 Compensation per employee in the U.S. software industry

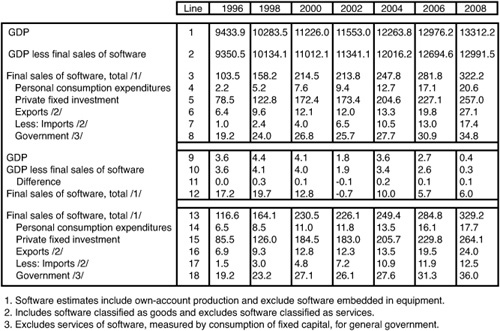

In terms of the software industry’s contributions to the gross domestic product, Figure 5.3, from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, shows a steady increase from the years 1995 to 2008.5

Figure 5.3 GDP and final sales of software

A Global Opportunity

The information technology industry will continue to benefit businesses and individuals around the world. Even though the 2008 financial industry meltdown had a significant impact across the globe, and IT spending experienced a dip during the recession, a tremendous number of investments continue to be made in IT. According to industry analysts at Gartner, the enterprise software market will grow to nearly $300 billion by 2013, averaging an annual growth rate of 5.4 percent.6 Additionally, a 2009 study conducted by industry analysts at IDC and sponsored by Microsoft found that global spending on IT will create 5.8 million new jobs between 2009 and 2013.7

From the outside looking in, it appears that we don’t lack for innovation or opportunity when it comes to the IT sector. However, several factors can interrupt progress and throw those future projections off course.

The Global Risks 2010 report from the World Economic Forum highlights the fact that underinvesting in infrastructure is one of the biggest risks to the global economy.8 From a broader perspective, infrastructure in this context refers not only to technology but also to other sectors that sustain us, including energy and agriculture. The report also outlines the impact of the growing interconnectedness among all areas of risk, including economics, geopolitics, environment, society, and technology. That interconnectedness, when combined with the financial meltdown, increases the need for greater global governance across governments and the private sector. However, gaps in this governance exist.

When applied appropriately, technology can help sustain the interconnectedness and enable governments and businesses to work together more closely to close governance gaps.

The Past Is Prologue: A Brief History of the IT Industry

To better prepare for the future, we must first understand the past. With this in mind, let’s take a moment to recap three of the most critical evolutionary phases in the IT industry:

• The mighty mainframe and the back office

• Revolution in the front office

• Massive globalization through the Internet era

The Mighty Mainframe and the Back Office

The back-office era gained momentum in the 1960s as companies with large budgets invested upwards of $1 million to get their hands on a mainframe. These mainframes were housed in large air-conditioned rooms and were tended to by teams of technicians wearing white coats. These technicians were responsible for performing what was then considered sophisticated data analysis using punch cards.

As an aside, history buffs will be quick to point out Herman Hollerith and the role of punch cards in the 1890 census.9 Hollerith founded the Computer Tabulating Recording Company, which later was renamed International Business Machines Corporation (IBM).10

From the day-to-day view of computing in the office, the mainframe was just beginning to change the shape of things in the 1960s. The industry responded to the high costs of the mainframe with the introduction of minicomputers, which were smaller and less powerful yet still a viable alternative. The first minicomputer, created by Digital Equipment Corporation, debuted in 196511 and was priced at approximately $16,000. Although the minicomputer and its cousin, the mid-range, are rarely seen today, their accessibility and power helped expand the role of computers in business.

The mid-1960s and 1970s were primarily characterized by the then-radical deployment of mainframe and minicomputers to automate and organize a wide range of back-office functions such as accounting, inventory tracking, payroll, and compiling human resources data. By today’s standards, these were simple tasks. As decision makers at companies became more aware of the computer’s ability to help streamline back-office functions, technology in the workplace started to take on a larger role.

Today, the power of the mainframe has yet to be usurped. The mainframe has been in place at some companies for decades due to its strength, which is sustained by the leading mainframe providers. These include IBM; Hewlett-Packard through its acquisition of Compaq, which acquired Digital Equipment Corporation; and Oracle through its acquisition of Sun Microsystems.

Given the life span of the mainframe, it’s almost impossible to grasp just how much information it has been able to help companies accumulate and process over the years. The mainframe represents a significant portion of a company’s IT budget, and it’s becoming even more expensive to maintain. These costs include the following:

• Staffing

Staffing

As we’ve discussed, a potentially costly expense is associated with the IT knowledge drain, especially when it comes to COBOL programmers who are essential to the ongoing maintenance of mainframes. While the mainframe will continue to be a mainstay, the shortage of skilled programmers and those who are interested in supporting them will affect nearly every business that even remotely relies on these technology workhorses.

MIPS Consumption

MIPS stands for millions of instructions per second and is generally used to refer to the processing speed and performance of larger computers. In this context, we’re referring to how quickly and efficiently a mainframe can process a transaction. From an economical point of view, MIPS helps you determine how much money each of those transactions will cost to process. The more data we have, the more data we need to process, which drives up MIPS consumption. Reducing the cost of MIPS is a priority for companies, especially as we continue to increase our data transaction loads on the mainframe.

Rising Energy Costs

The size of the mainframe and its extreme processing power require a significant amount of energy to run, which drives up the cost of ownership. In many instances, mainframes are located offsite in a data center. So not only do you pay for the offsite location, but data center energy costs can be 100 times higher than those for typical buildings.12 Companies are very mindful of the rising costs of energy and how that affects the environment, especially since data centers will account for 3 percent of total U.S. electricity consumption in 2011.13 Businesses and government agencies are addressing this issue, yet it will remain a concern for the foreseeable future.

Revolution in the Front Office

As the role of technology became more widespread, partly as a result of the productivity gains achieved through the mainframe, we entered the era of the front office. This expansion was primarily the result of the mass adoption of personal computers in the 1980s.

Much like the mainframe automated back-end tasks, the personal computer put similar processing power on the desktops of knowledge workers and streamlined the bulk of clerical tasks. Traditional office tools such as typewriters, accounting ledgers, and overhead projectors were replaced by word processing software, spreadsheets, and presentation applications.

This second wave of IT innovation formed the foundation of today’s integrated enterprises. Although the desktop experiences of individual knowledge workers were clearly enhanced during this era, it wasn’t until the introduction of e-mail and voice mail in the 1990s that technology really became front and center in the workplace. Thankfully—and, on some days, regrettably—these advances paved the way for the always-on businesses of today.

Massive Globalization Through the Internet Era

The third wave is most clearly defined by the Internet gold rush. As we saw with previous technology-inspired booms such as railroads in the 1840s, automobiles and radio in the 1920s, and transistor electronics in the 1950s, the Internet era led to new wealth-creation models.

Just how much wealth creation are we talking about? Looking at U.S. Census Bureau data, the information/communications/technology-producing industries contributed $855 billion to the $11.6 trillion total GDP in 2008. This number in 1990 was a mere $100.6 billion of the $7.1 trillion total GDP.14

Equally important, if not more so, were the new business models that the Internet introduced as easier access to the global economy represented significant opportunities. The competition that sprang up from seemingly unexpected places helped fuel innovation and a focus on customer service. Not only are we now faced with competition from all over the globe, but we also have to contend with dissatisfied customers alerting the world to their experiences.

Changing Business Models

Amazon.com’s emergence during this period is worth a closer look, because the company was transparent about the fact that it wouldn’t become profitable for several years. In a climate of instant gratification and get-rich-quick ideas, Amazon.com proved the importance of a sound business plan. Meanwhile, a good many dotcoms imploded around Amazon, and bricks-and-mortar establishments scrambled to figure out their online strategy. After an eight-year stretch, not only did Amazon prove its naysayers wrong, but it also now dominates the e-commerce market.

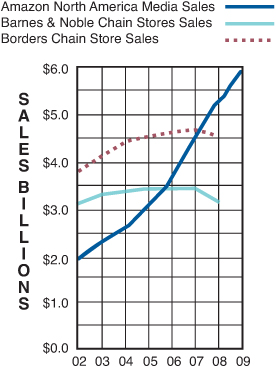

Just look at how Amazon has grown through the years in book sales alone. Figure 5.4 compares Amazon with leading booksellers Barnes & Noble and Borders.15 Amazon is one of many companies that emerged successfully from the Internet era. It proves that you should never underestimate the power of a well-formed strategy—and, more importantly, you should never take your position for granted.

Figure 5.4 Amazon’s sales growth versus major competitors

Conversely, as the world got more flat vis-à-vis the Internet, casualties occurred in existing business models. For example, to serve an overseas customer base, Lotus was burning, assembling, shrink-wrapping, and shipping software CDs. The job creation associated with managing and packaging the warehouse inventory contributed to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts’ economy as well as the economies of overseas distributors. As the Internet evolved, shrink-wrapped software was replaced by simple downloads, eliminating the need for warehouses. This directly affected the livelihood of employees in adjacent industries, including printing, design, packaging, and manufacturing.

In the latter half of the 2000s, we saw another shift brought on by Web 2.0. The explosion of social media tools, for better or worse, dramatically changed how we create, interpret, digest, and share information and news throughout companies and with our friends and family.

When our traditional media outlets shrank or disappeared, we saw the creation of smaller, niche communities of experts. As the traditional media playing field was leveled, up popped thousands of smaller outlets that filled the gap with up-to-the-minute news, information, and speculation. Instead of reading one national newspaper, we now customize our news feeds based on certain bloggers, discussion forums, Twitterati, and highly focused media outlets.

Along with the benefits of those customized feeds comes the deluge of data that needs to be analyzed, categorized, and otherwise waded through for it to make sense. The challenge for all of us is keeping up with this volume. Consumers must manage information and properly categorize it as it relates to their jobs and interests. Also, since the second era in computing boosted productivity through personal computers, knowledge workers are now constantly creating new and different forms of data to perform their jobs. From an IT perspective, the exponential growth in data is draining the network and adding to the mainframe’s workload. Given all the information that needs to be managed, I suspect many IT departments often feel like some days at work are like a never-ending game of whack-a-mole.

With every major shift in the IT industry, compromises had a domino effect on parts of, if not entire, tangential industries. Some are more obvious, such as the situation with Lotus packaging or the economics of the traditional publishing model, which also affects advertising agencies, printers, and even college journalism curricula.

Other shifts are less public and more widespread and slowly creep up on us—at least, that’s how the Great Recession initially appeared.

The Impact of the Great Recession

In late 2008 and throughout 2009, the phrase “too big to fail” made its way from financial regulation circles to dinner tables as bad news continued to be reported about the collapse of the financial industry as we knew it. Along with the news came a crash course in economics. We soon learned about the sub-prime lending that led to the near-collapse of the housing market, as well as what overleveraging and opaque financial reports mean to the sustainability of an economy. We also learned that the recession actually began in 2007.16

Those who were less interested in complex economic models simply wanted to know why the cost of commodities such as oil and food was going through the roof while uncertainties about employment and retirement funds were looming. When simple explanations were not so simple, lots of fingers were pointed toward individuals and groups who were deemed responsible for what is now viewed as the deepest and widest recession since the Great Depression.

Looking to identify one source or a single inciting incident for the recession is impossible, because various factors came together to create the situation. Some blame goes as far back as the Carter and Clinton Administrations. Others believe it was the result of the housing boom and the subprime lending that was made available to unqualified consumers who eventually defaulted on their charge cards and mortgages.

There’s no doubt that the recession of the late 2000s will continue to be studied in classrooms and boardrooms for years to come. In light of the many dimensions that led to the recession and sectors that were affected by it, the following sections take a closer look at it from an IT perspective by exploring these topics:

• Bernie Madoff: a catalyst for change

• Massive mergers and acquisitions pressure the IT infrastructure

• The benefits of transparency in business processes

Bernie Madoff: A Catalyst for Change

Greater transparency may have stemmed or perhaps halted the extent of the damage caused by Bernie Madoff, a former Wall Street investment advisor and arguably the most widely hated white-collar criminal.

Madoff was a stockbroker and chairman of the NASDAQ stock market before he ran the world’s largest hedge fund. The hedge fund turned out to be the longest and most widespread Ponzi scheme in history17 as Madoff bilked clients out of more than $65 billion under the guise of financial investments and advice. Many signs of misconduct and complaints were brought before the public.18 The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)19 admitted that Madoff’s financial activities were illegal. Unfortunately, the scam wasn’t properly addressed until it was too late.

From an IT perspective, we learned that one of Madoff’s tricks was to punch fake trades into an old midrange computer. Madoff controlled all access to the computer and entered share prices that aligned with his so-called financial returns.20 Because he rigged the computer, the trades and reports looked accurate to the untrained eye. The fact that Madoff was also viewed as a Wall Street trading technology pioneer helped him carry on his behavior for decades.

Madoff’s behavior begs the questions that many of us are still asking. Where was the transparency into Madoff’s dealings, and where was the transparency within the IT infrastructure? The SEC has instituted new policies and procedures since Madoff was discovered to be a fraud. With its Post-Madoff Reforms,21 the Commission has revamped nearly every aspect of its operations in an effort to provide greater transparency and to mitigate the risks that allowed Madoff to carry out his activities.

From an IT point of view, the SEC reforms call for more centralized management of information and tighter controls to more effectively alert officials to potential red flags. The SEC’s actions, in my view, underscore the importance of IT governance to help increase visibility into computer-related transactions.

Is another Madoff situation lurking in an IT infrastructure? We may not know until it’s too late. As a body that oversees the health of the financial industry, the SEC is in a position to effect more change from an IT perspective. Therefore, backroom computers like the one that Madoff used are no longer viable unless they meet specific IT governance requirements mandated by the Federal government. If IT governance principles were applied to and enforced in the infrastructures that are responsible for executing financial transactions, there would be a greater likelihood that those red flags would be identified before the transactions were executed or consumer complaints were formally reported to the SEC.

Massive Mergers and Acquisitions Pressure the IT Infrastructure

One of the sectors most dramatically affected by the recession was financial services. According to Thomas Philippon, an economist at New York University’s Stern School of Business, the financial sector lost 548,000 jobs, or 6.6 percent of that industry’s workforce, during the Great Recession.22

With the sector’s consolidation came significant mergers that required massive IT integration to bring together the newly formed companies. Some of the bigger ones included Bank of America’s $50 billion merger with Merrill Lynch23 and Wells Fargo’s $15.1 billion merger with Wachovia.24

The term massive undertaking is an understatement when it comes to accurately portraying the work associated with merging the back-end systems of financial institutions without disrupting service to customers.

As any IT professional can attest, bringing together two different organizations of any size is never as straightforward as it may initially appear, even when the most comprehensive strategy has been mapped out by IT and business professionals. This is especially true when you consider that you’re often bringing together two completely different infrastructures, cultures, and sets of business processes.

Although overlaps may occur in the technology that’s in place at the individual companies, there will be variables in terms of how the software was customized to address specific business functions that are part of the fabric of those individual organizations.

Still, a merger also presents opportunities, because it forces you to evaluate best practices, policies, and existing technologies. What is often uncovered are what I call “potholes” in the infrastructure. These are the small, often contained glitches that may be found in applications, in web services, or within parts of a platform. They often go undetected because the information gets to its intended recipients—eventually. Only when these potholes disrupt the flow of data or stall productivity do we address them.

At the heart of any successful integration project is the software code. After all, the applications and systems can’t work together properly if the code is faulty. In many instances, the code may not be completely erroneous, but it does go against internal IT policies and best practices and, sometimes, better judgment.

Even if the code does pass inspection, it will eventually show signs of shoddy workmanship in the form of system failures, software glitches, and the like. Since integration can be an extensive and expensive project, and parts of it tend to be tedious, you can automate some of the more mundane tasks. Yet you have to determine how much you want to automate and how much will still require real live project team leaders to oversee the process. The goal is to strike the right balance between the two.

As companies continue to merge and more devices and computers are connected to the Internet, we will see more of these “potholes,” because they are no longer isolated. However, if we know where they are, we can do something about them before it’s too late.

Mergers and the Disappearing Bank Balance

One of these oversights in the IT infrastructure affected customers of TDBank in 2009 when it was in the midst of its integration with Commerce Bank.25 Thousands of banking customers were locked out of their accounts and couldn’t accurately reconcile their statements. This happened because of a glitch that didn’t accurately track balances and caused delays in recognizing automatic payroll deposit checks.

Martin Focazio and his wife were customers of both TDBank and Commerce Bank at the time of the post-merger integration. He shared their experiences with me for this book.26 Martin had set up his payroll direct deposit to go into his TDBank account, and it had successfully worked this way for years. Since the Focazios are diligent about checking their bank balance every day, his wife noticed immediately when the bank didn’t record the direct deposit.

After Focazio’s wife made several phone calls to TDBank and was put on hold for up to 40 minutes, Martin turned to Twitter to find out if anybody else had been affected by this glitch. He discovered that other customers had the same experience, though he had yet to be notified by the bank. While he scrambled to withdraw cash from other sources to cover monthly expenses, it was not the most convenient situation, to say the least.

“We were lucky that we had the funds to cover our bills,” said Focazio. “A lot of people these days don’t, and while the bank said they’d cover interest and fees, that’s not a lot of help to people who will be charged high interest on their late balances and can potentially put their credit scores at risk. It’s a downward spiral if you’re living paycheck to paycheck and are hit with a series of late fees and high interest rates because the bank made a mistake.”

By consistently calling the bank and checking their balance online, the Focazios realized that the issue was later fixed, yet they never received notification from the bank beyond a posting on its website. Then, according to Focazio, “the exact same thing happened two weeks later.” This second offense is what led the Focazios to switch banks. I suspect that they were not the only customers to do this.

These issues go beyond the financial services industry. Dana Gardner, IT analyst and founder of Interarbor Solutions, shared his opinion on this topic and on the impact of glitches during our interview.27 “Increasingly, when I personally find fault with a business, process, government, service, or product, I think about how well the company, community, government, or ecosystem develops software.

“If I’m on hold for 20 minutes when I call a global bank for a reason that legitimately requires a customer service representative, that’s a software life cycle failure,” said Gardner. “When I buy a flat-panel TV and it takes me four hours to make it work with the components, that’s a software life cycle failure. When I wait for three hours for what was supposed to be a one-hour brake pad replacement, that’s a software life cycle failure. The degree to which software and processes are mutually supportive and governed determines how things fall apart, or how they need to be fixed.”

Now is the time for an increased focus on preventive best practices in IT across all industries—before the recent trends in highly visible computer glitches described here become truly debilitating.

The Benefits of Transparency in Business Processes

The situation with Madoff, as well as the need to avoid glitches in everyday business transactions, point out the growing need for transparency in the IT infrastructure. The complementary combination of IT governance and compliance can help deliver that transparency. Yet where it’s applied and how much is required depend on the industry and the company itself.

A common misperception is that introducing a greater level of transparency into the infrastructure requires that a company hire a team of experts and spend unnecessary money on adding more technology to an already complex IT environment. When applied properly, compliance and IT governance can enable a company to more effectively mitigate any risks to the business before they impede performance or erode the bottom line.

This argument becomes stronger when you realize that nearly 55 percent of a company’s software applications budget is consumed by supporting ongoing operations.28 If some of the maintenance efforts can be executed using automated governance, this can free up the IT staff to focus on more strategic efforts.

Additionally, with greater transparency into the IT infrastructure, we will be better able to determine the source of the glitch for greater accountability. We may also be able to retire the convenient and sometimes questionable “It must have been a computer glitch” excuse.

When we step back and take a closer look at the changes in business driven by technology in just over a few decades, we’re reminded of how complex our infrastructures can be. If the introduction and on-going maintenance of technology is not managed properly, we are leaving our businesses and customers more vulnerable to the creation and distribution of glitches.

Although we can’t go back in time, we can move forward by creating greater transparency into the IT infrastructure. This transparency must be delivered across the entire company and not trapped in a department or division. Otherwise, we risk perpetuating the cycle of silo-based information that inhibits growth and productivity and ultimately leads to failed IT projects.

According to Michael Krigsman, CEO of Asuret, a consultancy specialized in improving the success rate of enterprise technology initiatives, “Most IT projects fail before they even begin. Poor governance, lack of clear project strategy and goals, insufficient executive support, and so on militate against project success.”31

Critical Success Factors for the Future

In the interest of illustrating the hidden impact of faulty software, we’ve highlighted technology’s influence on the global economy, covered the history of the industry, and touched on the latest recession. Here are the critical takeaways from these inflection points in the IT industry:

• One of the keys to sustaining global growth is to have the IT sector lend its expertise to ensure continued connectedness among governments and businesses worldwide. The IT industry should consider donating services and technology to support connectedness among the areas most in need of closing governance gaps.

• Energy efficiency will remain a top priority for businesses. It’s worth considering working only with vendors that can demonstrate their ability to support the most energy-efficient IT infrastructures. In the U.S., the Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Energy have created Energy Star label certifications for the data center, which will help clients validate the efficiency of their IT provider.29

• The financial services sector, while already heavily regulated, could benefit from additional IT governance. This includes the federal enforcement of technology-driven policies that instantly alert the proper government agencies and overseeing boards to stop potentially fraudulent activity.

• Mergers and acquisitions will continue to impact the IT infrastructure. But companies shouldn’t wait for a merger or other external force to assess the health of their infrastructure. Build transparency into the IT infrastructure so that you always have an up-to-the-minute status on all activities.

• Successful mergers and acquisitions are possible when a cross-functional team is dedicated to the integration strategy. This includes a focus on the customer experience and a well-paced transition that occurs in time to allow the integration to be tested in various user scenarios before the system goes live.

Technology will continue to influence global markets, but we’re still in the nascent stages of our globally connected economy. Some 60 percent of the world’s population has never had contact with information technologies, and the majority of content that is being disseminated over the Internet is meant for developed societies.30

This data will change as the industry continues to evolve. However, the benefits will be negated unless IT organizations and government leaders make a concerted effort to eliminate the obvious obstacles to advancement. These obstacles include lack of governance, the need for more organized task forces dedicated to global IT advancement, and greater transparency across all business processes.

Endnotes

1. United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Outlook Handbook 2010–11.

2. United States Business Software Alliance.

3. Organization for Economic and Co-Operation and Development. STAN Database for STructural ANalysis (STAN) Indicators Database, ed. 2008.

4. Ibid.

5. U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. GDP Software Investment and Prices. August 27, 2009.

6. Gartner. Forecast: Enterprise Software Markets, Worldwide, 2008–2013, 1Q09 Update. March 16, 2009.

7 IDC. “Aid to Recovery: The Economic Impact of IT, Software, and the Microsoft Ecosystem on the Economy.” October 2009.

8. World Economic Forum. “Global Risks 2010.” January 2010.

9. U.S. Library of Congress. Hollerith’s Electric Tabulating and Sorting Machine. 1895.

10. U.S. Census Bureau: History. Herman Hollerith. http://www.census.gov/history/www/census_then_now/notable_alumni/herman_hollerith.html.

11. Digital Computing Timeline. http://vt100.net/timeline/1965.html.

12. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Data Center Energy Management. http://hightech.lbl.gov/DCTraining/.

13. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Report to Congress on Server and Data Center Energy Efficiency. August 2, 2007. http://hightech.lbl.gov/documents/DATA_CENTERS/epa-datacenters.pdf.

14. U.S. Census Bureau. Gross Domestic Product by Industry Accounts, Real Value Added by Industry. Release date April 28, 2009.

15. Amazon growth chart. http://www.fonerbooks.com/booksale.htm.

16. National Bureau of Economic Research. Determination of the December 2007 Peak in Economic Activity. http://www.nber.org/cycles/dec2008.html.

17. New York Times. “Madoff Is Sentenced to 150 Years for Ponzi Scheme.” Diana B. Henriques. June 29, 2009.

18. Barron’s. “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” Erin Arvedlund. May 7, 2001. http://online.barrons.com/article/SB989019667829349012.html.

19. “The World’s Largest Hedge Fund Is a Fraud.” November 7, 2005 submission to the SEC. Madoff Securities, LLC. United States Securities and Exchange Commission. http://www.sec.gov/news/studies/2009/oig-509/exhibit-0293.pdf.

20. Too Good to Be True: The Rise and Fall of Bernie Madoff. Erin Arvedlund. Portfolio Hardcover, 2009.

21. United States Securities and Exchange Commission Post-Madoff Reforms. http://www.sec.gov/spotlight/secpostmadoffreforms.htm.

22. Wall Street Journal. “Even if the Economy Improves, Many Jobs Won’t Come Back.” Justin Lahart. January 12, 2010.

23. Bank of America press release. Bank of America Buys Merrill Lynch Creating Unique Financial Services Firm. http://newsroom.bankofamerica.com/index.php?s=43&item=8255.

24. Wells Fargo press release. Wells Fargo, Wachovia Agree to Merge. https://www.wellsfargo.com/press/2008/20081003_Wachovia.

25. Network World. “TDBank Struggles to Fix Computer Glitch.” Jaikumar Vijayan. October 2, 2009. http://www.networkworld.com/news/2009/100209-td-bank-struggles-to-fix.html.

26. Interview with Martin Focazio by Kathleen Keating. January 2010.

27. Interview with Dana Gardner by Kathleen Keating. January 2010.

28. Forrester Research. “The State of Enterprise Software and Emerging Trends: 2010.” February 12, 2010.

29. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. Department of Energy. Enterprise Server and Data Center Energy Efficiency Initiatives. http://www.energystar.gov/index.cfm?c=prod_development.server_efficiency.

30. World Economic Forum. Update: 2008. http://www.weforum.org/en/knowledge/Industries/InformationTechnologies/KN_SESS_SUMM_23553?url=/en/knowledge/Industries/InformationTechnologies/KN_SESS_SUMM_23553.

31. Interview with Michael Krigsman by Kathleen Keating. May 2010.