Assessing a Company’s Resource Base and Capabilities for Going Global

Introduction

This chapter focuses on how managers can identify the key company resources and capabilities around which they can build successful global strategies.1 The resource-based view (RBV) of a firm is an important framework for conducting this type of analysis. This approach examines a variety of specific types of resources and capabilities that all firms possess in some form and then evaluates the degree to which they serve as the basis for creating a sustained competitive advantage based on industry and competitive considerations.

Next, we review the concept of core competencies and its relation to strategy formulation and the development of a global competitive advantage. We conclude this part of the chapter by examining how managers can use their performance records and financial prospects to benchmark against existing competitors in global industries as a basis for gauging the likelihood of success when entering a new global market.

The chapter’s balance deals with three issues that are critical to global success—a global mindset, talent, financial resources, and a commitment to open innovation.

The Resource-Based View of the Firm

Toyota versus Ford is a competitive situation that virtually all of us recognize. Stock analysts look at the two and conclude that Toyota is the clear leader. They cite Toyota’s superior intangible assets (newer factories worldwide, research and development (R&D) facilities, computerization, cash, etc.) and intangible assets (reputation, quality control culture, global business system, etc.). They also mention that Toyota leads Ford in several capabilities to use these assets effectively. Examples include managing distribution globally, influencing labor and supplier relations, managing franchise relations, customer-responsive marketing, and using the speed of decision making to take quick advantage of changing global conditions are a few. Combining capabilities and assets creates competencies for Toyota that are vital, durable, and not easily imitated competitive advantages over Ford.

The Toyota–Ford example illustrates several concepts central to the firm’s RBV. The RBV is a method identifying and analyzing an organization’s strategic advantages based on its distinct combination of assets, skills, capabilities, and intangibles as an organization. RBV’s underlying premise is that firms differ in fundamental ways because each firm possesses a unique set of resources to use those assets. Each firm develops competencies from these resources, and, when developed exceptionally well, these become the source of the firm’s competitive advantages. Toyota’s unmatched decisions to enter global markets locally and regularly invest in or build factories in global markets produced a competitive advantage that led to distinctive competencies and a sustainable competitive advantage.

Tangible Assets, Intangible Assets, and Organizational Capabilities

The RBV’s ability to create a more focused, measurable approach to internal analysis starts with its delineation of three basic types of resources. Tangible assets are the most straightforward resources to identify and are often found on a firm’s balance sheet. They include financial resources, raw materials, production facilities, real estate, and computers. Tangible assets are the physical means a company uses to provide value to its customers. Intangible assets are resources without a physical quality such as brand names, company reputation, employee morale, technical knowledge, accumulated experience within an organization, patents, trademarks, and copyrights. Organizational capabilities are skills—the ability and ways of combining assets, people, and processes—that a company uses to transform inputs into outputs.

What Makes a Resource Valuable?

After managers identify their firm’s tangible assets, intangible assets, and organizational capabilities, they can answer four questions to determine the resources contributing to core competencies and ultimately sustain competitive advantage. The RBV argues that resources are more valuable when they satisfy all four of these guidelines.

1. Is the resource or skill critical to fulfilling a customer’s need better than that of the firm’s competitors?

Walmart redefined discount retailing and outperformed the industry in profitability by emphasizing four resources—store locations, brand recognition, employee loyalty, and sophisticated inbound logistics. These emphases allowed Walmart to fulfill customer needs much better and more cost-effectively than other discount retailers. The insight from this example is that managers need to identify the few resources that contribute to competitive superiority in, especially, valuable ways. Other resources at Walmart contribute little to competitive advantages because they do not help fulfill customer needs better than those of its key competitors. Examples include the restaurant menu, specific products offered, or parking spaces.

2. Is there a scarce supply of the resource, or is it easily substituted for or imitated?

Short supply. When a resource is scarce, it is more valuable. When a firm possesses a critical resource, and few other competitors do, it can become the basis of competitive advantage. Very limited natural resources, a unique location, and skills that are truly rare represent scarce resources.

Availability of substitutes. A substitute product is one that the customer can purchase instead of ours to do the same task. It is a different product from a different industry, not a different brand of the same industry product. Examples include printers instead of copier machines, cigarettes instead of e-cigarettes, and solar power instead of coal power.

Imitation. A resource that competitors can readily copy can only generate temporary value. It is scarce for only a short time. Competitors will match or better a resource as soon as they can. Thus, the firm’s ability to forestall the competitor’s imitation is critical. The RBV identifies four characteristics, called isolating mechanisms, that make resources difficult to imitate:

• Physically unique resources are virtually impossible to imitate. A one-of-a-kind real estate location, mineral rights, and patents are examples of resources that cannot be imitated. While there are claims that resources are physically unique, this is seldom true in an impactful way.

• Path-dependent resources are challenging to imitate because of the vague and complicated path a competitor must figure out and replicate to recreate the resource. These resources must be created over time in a very expensive manner and always difficult to accelerate. Google’s creation of proprietary search algorithms, Gerber Baby Food’s reputation for quality, and Steinway’s piano manufacturing expertise would take competitors many years and millions of dollars to match. Consumers’ experience drinking Coke or using Gerber, or playing a Steinway would also need to be matched.

• Causal ambiguity refers to situations in which it is difficult for competitors to understand precisely how a firm has created the advantage it enjoys. Such causally ambiguous resources are often organizational capabilities that arise from subtle combinations of tangible and intangible assets and culture, processes, and organizational attributes.

• Economic deterrence usually involves large capital investments incapacity to provide products or services in a given market that are scale-sensitive. Economic deterrence occurs when a competitor understands the resources and may even have the capacity to imitate but chooses not to engage because of a limited market size that would not support an additional firm.

3. Appropriability: Who actually gets the profit created by a resource?

Because the Walt Disney Company owns the Mickey Mouse copyright, all profits from that valuable resource accrue to Disney. The value of the franchise name, reservation system, and brand recognition are other examples of appropriability that may be critical in generating the business’s profits. Also, many appropriability cases result from employee skills and knowledge that develop within the firm and cannot be transferred readily or effectively to another company.

4. Durability: How rapidly will the resource depreciate?

The slower a resource depreciates, the longer its value is maintained. Tangible assets are measurable, and the rate of decline in their value can be estimated. It is challenging to estimate intangible resources’ future value, even if intellectual property protections cover them. Thus, they present a much more difficult depreciation or amortization challenge. In the increasingly hypercompetitive global economy, distinctive competencies, and competitive advantages can fade quickly, making the durability of a resource a critical test of value.

Core Competencies

A core competence is a capability or skill in which a company excels that it can leverage in the pursuit of its overall mission. Core competencies that differ from those found in competing firms would be considered distinctive competencies. Apple’s competencies in pulling together available technologies, Toyota’s pervasive organizationwide pursuit of quality, and Wendy’s systemwide emphasis on providing fresh meat each day are examples of unique competencies to these firms and distinctive compared to their competitors. Distinctive competencies enable a firm to provide products, services, and technologies superior to those of competitors, thus becoming the basis for a lasting competitive advantage for the company.

Core competencies evolve as a firm develops its business model. Core competencies are sets of skills or systems that create high value for customers at best-in-class levels. To qualify, such skills or systems should contribute to perceived customer benefits, be difficult for competitors to imitate, and allow for leverage across markets. Honda’s use of small engine technology in various products—including motorcycles, jet skis, and lawnmowers—is a good example.

Core competencies also benefit innovation. For example, Charles Schwab successfully leveraged its core competency in brokerage services by expanding its client communication methods to include the Internet, telephone, offices, and financial advisors. For further examples of core competencies, see Exhibit 5.1.

Hamel and Prahalad suggest three tests for identifying core competencies: (1) core competencies should provide access to a broad array of markets; (2) they should help differentiate core products and services; and (3) core competencies should be hard to imitate because they represent multiple skills, technologies, and organizational elements.2

Few companies have the resources to develop more than a handful of core competencies. Picking the right ones, therefore, is key. “Which resources or capabilities should we keep in-house and develop into core competencies, and which ones should we outsource?” is an important question to ask. Pharmaceutical companies, for example, often outsource clinical testing to focus their resources on drug development. Generally, core competencies focus on long-term platforms to adapt to market circumstances, sources of leverage in the value chain where the firm can dominate, important elements to customers, and key skills and knowledge, not on specific products.

Company |

Core Competencies |

Applications |

Proprietary algorithms for the Internet |

Online search, e-mail, Google maps |

|

Honda |

Small, reliable, powerful combustion engines |

Cars, boats, lawnmowers |

IKEA |

Modern functional home furnishings at low prices |

Fully furnished room setups, do-it-yourself (DIY) |

McKinsey |

Developing practice-relevant knowledge, insight, and frameworks |

Management and strategy consulting |

Starbucks |

High-quality beverages served in a unique ambiance |

Customized beverages, seasonal drinks, free Wi-Fi |

Tesla |

High-performance battery-powered motors and power trains |

Cars, trucks |

UPS |

Superior supply chain services at low cost |

Package tracking and delivery, ecommerce |

Exhibit 5.1 Examples of core competencies

To develop core competencies, a company must take several actions3:

• Isolate its key abilities and hone them into organizationwide strengths

• Compare itself with other companies with the same skills to ensure that it is developing unique capabilities

• Develop an understanding of what capabilities its customers truly value and invest accordingly to develop and sustain valued strengths

• Create an organizational roadmap that sets goals for competence building

• Pursue alliances, acquisitions, and licensing arrangements that will further build the organization’s strengths in core areas

• Encourage communication and involvement in core capability development across the organization

• Preserve core strengths even as management expands and redefines the business

• Outsource or divest noncore capabilities to free up resources that can be used to deepen core capabilities.

Benchmarking: Comparison With Competitors

A firm’s primary focus in determining the value of its resources and competencies is to compare itself with existing and potential competitors. Firms in the same industry develop and rely on similar resources, competencies, and skills in functional areas and operating facilities and locations, technical know-how, brand images, levels of integration, managerial talent, and so on. However, when there are differences in internal resources, they can build relative strengths and essential considerations in strategy formulation.

The largest technology companies in the world are resource-rich, as is required for the production of cellphones and laptop computers. The list of the largest global competitors, based on market capitalization, include Accenture, Adobe, Alphabet, Apple, Broadcom, Cisco, Facebook, IBM, Intel, Microsoft, NVIDIA, Oracle, Qualcomm, Salesforce, Samsung, SAP, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing, Tata Consultancy Services, Tencent, and Texas Instruments. In many cases, these companies are head-to-head competitors in the global tech-services industry. Because they have a shared reliance on many resources and capabilities, benchmarking is a useful tool in determining how a company stands in the race to provide attractive customer segments with the most demanded product characteristics.

For example, New York-based IBM and India-based Tata Consultancy Services are major rivals. Tata focuses on large American and European companies by providing lower-cost information technology (IT) services and business process simplification consulting. By contrast, IBM focuses on helping clients cut costs and emerging market customers build their technology infrastructures.

Tata’s strength is its ability to offer low-cost outsourcing options to large firms for their information system operation needs. IBM emphasizes systems design and optimization of the latest technology infrastructure to make systems perform well. IBM also relies on its technical skills and computer technology expertise, where it maintains a relative strength.

These strategies produce a situation where Tata generates half of its global revenue from U.S. clients. By contrast, IBM generates half of its revenue in foreign nations, with particular success in selling tech services in India. Thus, managers in both Tata and IBM have built successful yet fundamentally different strategies. Benchmarking each other, they have identified ways to build on relative strengths while avoiding dependence on capabilities at which the other firm excels.

Benchmarking, which is defined as comparing how a company performs a specific activity with a competitor that does the same thing, is a central concern of managers in quality committed companies worldwide. Managers seek to systematically benchmark the costs and results of all value activities against relevant competitors or useful standards. It has proven to be an effective way to improve that activity continuously.

General Electric’s (GE’s) approach includes sending managers to benchmark FedEx’s customer service practices, seeking to compare and improve its practices within a diverse set of businesses, none of which compete directly with FedEx. It earlier did the same thing with Motorola, leading it to embrace Motorola’s Six Sigma program for quality control and continuous improvement.

The Importance of a Global Mindset

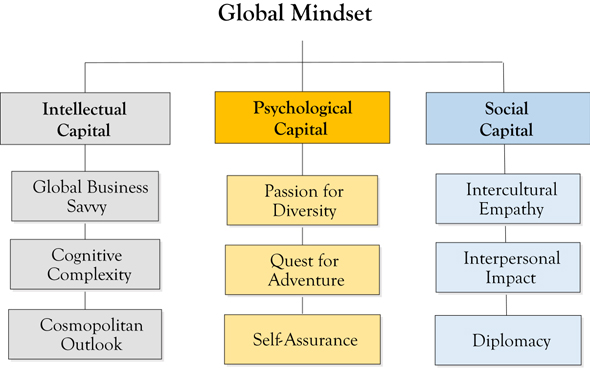

Many corporations encounter a common challenge, as they move to globalize their operations can be summed up in one word: mindset. Herbert Paul defines a mindset as “a set of deeply held internal mental images and assumptions, which individuals develop through a continuous process of learning from experience”.4 In a global context, a global mindset is “the ability to avoid the simplicity of assuming all cultures are the same, and at the same time, not being paralyzed by the complexity of the differences”.5 As Exhibit 5.2 shows, a global mindset has three main components. Intellectual capital, which describes the ability to deal with global complexities. Psychological capital defines the capacity and eagerness to deal with an unfamiliar situation. Finally, social capital assists in dealing with different cultures and situations requiring a high level of empathy.

The concept of a mindset does not just apply to individuals; it can be extended to organizations as the members’ aggregated mindset. At the organizational level, mindset also reflects whether its members interact mainly formally or informally and whether decision-making processes are hierarchical or informal. The personal mindset of the CEO sometimes is the single most important factor in shaping the organization’s mindset.

Exhibit 5.2 Elements of a global mindset

A corporate mindset determines how corporate challenges, opportunities, capabilities, and limitations are perceived. It also defines how goals and expectations are set and significantly impacts what strategies are considered and ultimately selected and implemented. Recognizing the diversity of local markets and seeing them as a source of opportunity and strength, while at the same time, pushing for strategic consistency across countries lies at the heart of global strategy development.

To understand the importance of a corporate mindset, consider two often quoted corporate mantras: “Think global and act local” and its opposite: “Think local and act global.” “Think global and act local” indicates a global approach based on the belief that a powerful brand name combined with a standard product, package, and advertising concept is the best way to succeed in global markets. Contrast this with a “Think local and act global” mindset, which assumes that global expansion, is best accomplished through adaptation to local needs and preferences. In this mindset, diversity is considered a source of opportunity, whereas strategic cohesion plays a secondary role. Such a bottom-up approach can offer greater revenue generation possibilities, particularly for companies wanting to grow rapidly.

To become truly global, multinational companies will increasingly have to look to emerging markets for talent. India is recognized as a source of technical talent in engineering, sciences, and software. Hightech companies recruit in India not only for the Indian market but also for the global market. China and other parts of Asia may be next.

As corporate globalization advances, senior management’s composition will also begin to reflect the importance of the emerging markets. At present, with a few exceptions, such as Citicorp and Unilever, C-suites are still filled with nationals from the company’s home country. As the senior management for multinationals becomes more diverse, decision-making criteria and processes, attitudes toward ethics and corporate responsibility, risk-taking, and team building will likely change. The changes in decision-making priorities may reflect a slow but persistent shift in many multinational companies’ attention toward Asia. In many Western countries, decision making is highly participative. In other words, many decisions are made based on a group majority, and participation is encouraged by subordinates and leaders. In many Asian cultures, a more systematic approach to governance and administration is preferred.

Determinants of a Corporate Global Mindset

What factors shape a corporation’s mindset? Can they be managed? Given the importance of mindset to a company’s global outlook and prospects, these are important questions. Paul cites four primary factors: (1) top management’s view of the world, (2) the company’s strategic and administrative heritage, (3) the company’s dominant organizational dimension, and (4) industry-specific forces driving or limiting globalization.6

Top management’s view of the world. The composition of a company’s top management and how it exercises power can influence the corporate mindset. A visionary leader can be a major catalyst in breaking down existing geographic and competitive boundaries. By contrast, leaders with a regional, predominantly ethnocentric vision, are more likely to concentrate on the home market and not be very interested in international growth.

Administrative heritage. The second factor is a company’s administrative heritage—its strategic and organizational history. This history reflects how the company has grown, what assets it has acquired over the years, the evolution of its organizational structure, the strategies and management philosophies the company has pursued, and its core competencies and corporate culture. In most companies, these elements evolve over several years and increasingly define the organization. Changing one or more of these key tangible and intangible elements of a company is an enormous challenge and, therefore, a constraint on its global strategic options.

Organizational structure. The type of organizational structure a company has adopted is also a key determinant of a corporate mindset. In a strongly product-oriented structure, management is more likely to think globally as the entire information infrastructure is geared toward collecting and processing product data worldwide. In an organization focused on countries or areas or regions, the managerial mindset tends to be more local because it is primarily oriented toward local and regional needs. In a matrix organizational structure based on both product and geographic dimensions, management’s mindset reflects both global and local perspectives.

Industry forces. Industry factors also affect managers’ perceptions and outlook. When there are opportunities for economies of scale and scope, global sourcing, and lower transportation and communication costs, managers are pushed toward a global efficiency mindset. Other factors that a global efficiency mindset include are (1) stronger global competition, (2) the need to enter new markets, (3) the globalization of important customers, (4) a trend toward more homogeneous demand, particularly for products in fast-moving consumer goods industries, and (5) more uniform technical standards, particularly for industrial products.

However, another set of industry drivers works in the opposite direction and calls for strategies with a high degree of local responsiveness. Such drivers include strong local competition in important markets and cultural differences, making the transfer of globally standardized concepts less attractive. Issues such as protectionism, trade barriers, and volatile exchange rates may also suggest a national or regional business approach.

Thus, to create the right global mindset, management must understand the different, often opposite, factors that shape it. At the corporate level, managers focused on global competitive strategies typically emphasize increased cross-country or cross-region coordination and more centralized, standardized approaches to strategy formulation. By contrast, country managers frequently favor greater autonomy for their local units because they feel they have a better understanding of the local market and customer needs. Thus, different managers can interpret data and facts differently and favor different strategic concepts and solutions depending on their mindsets.

In practice, two different scenarios can develop. The first is defined by a situation in which one perspective consistently wins at the other’s expense. Under this scenario, the company may well be successful initially. However, it is likely to run into trouble when its ability to learn and innovate is impaired as it opts for short-sighted solutions. A second scenario occurs when a deliberate effort is made to maintain a creative tension between both perspectives. This scenario recognizes the importance of such tension to the company’s ability to develop new ways of thinking and look for completely new solutions. A clear corporate vision and a commitment to fair decision-making processes are key to fostering and maintaining such creative tension. A clear corporate vision provides general direction for all managers and employees where the company wishes to be in the future. Accepted and well understood, fair decision processes encourage analysis and discussion of both global and local perspectives and their merits, given specific strategic situations.

Executive Talent Required for Going Global

To be successful in the world of international business demands a special set of skills. Global executives increasingly face a VUCA business environment—one that is volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous. The most important skills needed to navigate this new, globalized business landscape are soft skills. While strong technical know-how is still essential, the soft skills can mean the difference between survival and international business success.7 Key soft skills include (1) cross-cultural communication skills, (2) excellent networking abilities, (3) collaboration, (4) interpersonal influence, (5) adaptive thinking, (6) emotional intelligence, and (7) resilience.

Financial Resources

Expanding internationally requires significant financial resources. Financial resources are made up of a company’s liquid assets, including cash, bank deposits, and liquid financial investments, such as stocks and bonds. Corporations have three main sources of capital: (1) business operations, such as the sale of goods and services; (2) capital funding, including issues of shares and capital contributions; and (3) external sources such as bank loans or issues of corporate bonds.

Equity. Multinational companies have access to a number of options to raise funds beyond domestic financing. A global company can partner with investment banks to fund its expansion by issuing equity in exchange for cash in markets such as the stock exchanges in New York, Tokyo, London, and Hong Kong.

Debt. A second option is to raise funds by selling debt in the form of bonds. Selling debt products is a complicated process that is governed by strict regulations in most countries. Companies must clear several regulatory hurdles before being granted access to the credit market because holders of debt (creditors) have different legal rights from owners of stock (shareholders) when a company becomes insolvent. In addition to bonds, a global business entity can raise operating funds for its operations by selling commercial paper.

Private lenders. Offering equity or debt products in an open market is not the only way to raise funds from private sources. Private lenders such as banks, insurance companies, hedge funds, and private equity funds can often be more flexible and responsive, leading to faster funding than a well-regulated stock market can offer.

Government funding. Finally, an international company can form a corporation with public assistance. Government subsidies are generally targeted at attracting new businesses to a city or area, creating jobs and improving the local economy. If a corporation meets applicable regulatory requirements and is in an eligible line of business, a government subsidy can help provide much-needed funds for operational expenses.

A Commitment to Open Innovation8

In closed innovation companies, innovation occurs by using only internal resources. Internally generated new ideas are evaluated, and only the best and most promising ones are selected for their development and commercialization. The ones that show less potential are usually abandoned.

Open innovation companies use external knowledge, cooperate with external partners, and buy and incorporate external technologies and ideas. Innovations generated inside the company can be sold as new technology or industrial property to other companies. This makes sense if they are not applicable within their business model or because they have no capacity or experience to develop the invention.

There are significant advantages to opening the innovation process to the flow of ideas and knowledge in both directions:

• Reduction in the time and cost of innovation projects

• Development of a greater number of solutions, innovations, ideas, patents, products, and technologies

• Due to a lack of ability or strategic limitations, commercial inventions cannot always be introduced to the market

All three are pertinent to global strategy development. Timing can be key to entering a foreign market, as we will discuss in Chapter 8. Most products and services require a degree of adaptation to be accepted in foreign markets. Having local input into key decisions such as the degree and form of adaptation of the product or service, its manufacture and distribution, positioning, and branding can spell the difference between success and failure. Finally, the commercialization of ideas that do not fit with the current strategy provides additional revenue and often yields lasting partnerships with other companies.

Open innovation is based on five fundamental principles9:

1. “Not all smart people work for us, so we must find and tap external knowledge and expertise.”

2. “External R&D can create significant value; internal R&D is needed to realize some portion of that value.”

3. “Our company does not have to originate the research to use it profitably.”

4. “If we make the best use of internal and external ideas, we have a better chance to win.”

5. “We should profit when other companies use our intellectual property (IP), and we should buy the IP from other firms whenever it advances our business model.”

When engaging with universities, start-ups, customers, or suppliers, R&D laboratories developing new products or processes rely heavily on the firm’s support functions. However, there cannot be only a single open innovation champion within the organization. Innovation processes are complex and often involve different persons, departments, and disciplines. Therefore, different roles are required to help manage complex innovation projects. Three types of internal roles or promoters can help boost open innovation:

1. A power promoter drives a project, provides necessary resources, and helps overcome obstacles that might arise during a project.

2. The expert promoter is someone with specific technical or market knowledge for the innovation problem at hand and overcomes technical barriers.

3. The process promoter is the glue between the power promoter, the expert promoter, as well as other project members who contribute to an open innovation project but do not have the permission to do so due to existing internal rules or limited capacity and resources.10

GE is a company that employs various open innovation strategies. Its GE open innovation message emphasizes its comprehension of the need to address the world’s problems by applying crowdsourcing innovation. The Open Innovation Manifesto of the company highlights the collaboration between entrepreneurs and experts from anywhere to solve problems by sharing their ideas. Based on GE’s innovation Ecomagination project that targets to resolve environmental challenges via innovative solutions, the company, over the last decade, has spent 17 billion U.S. dollars on R&D and realized total revenues of 232 billion U.S. dollars.

Samsung adopted an open innovation strategy to build their external innovation strengths through the Samsung Accelerator program. This initiative aims to encourage collaboration between designers, innovators, and thinkers to focus on different solutions. Samsung divides its innovation cooperation projects into four categories: partnerships, ventures, accelerators, acquisitions. Partnerships typically aim for new features or integrations within Samsung’s existing products. Ventures can be described as investments into early-stage start-ups. These investments provide access to new technologies. For example, Samsung has invested in Mobeam, a mobile payment company. Accelerators provide start-ups with an initial investment, facilities to work in, and other resources. Products coming from the internal start-ups can become a part of Samsung’s product portfolio over time or just serve as learning experiences. Acquisitions are used to bring in start-ups working on innovations that are at the core of Samsung’s strategic areas of the future. These acquisitions often remain independent units and can even join the Accelerator program.

Hewlett–Packard (HP) was an early adopter of the ideals of open innovation. It has created an open innovation team that links collaborators with researchers and entrepreneurs in business, government, and universities to develop innovative solutions to hard problems to develop breakthrough technologies.

Procter and Gamble’s (P&G’s) open innovation with external partners is organized through its Connect+Develop website. Through this platform, P&G communicates with innovators who can access detailed information about specific needs and submit their ideas to the site. Connect+Develop has generated multiple partnerships and produced several new products.

Mini-Case 5.1: Dialing up Innovation at Nestle: Taking Open Innovation to a New Level Through a Multifaceted Approach11

By 2050, the world’s population is expected to reach almost 10 billion, making the supply of affordable foods more challenging than ever. Consumers are also beginning to demand healthier, natural, and more authentic food products and shift toward a plant-based diet. Sustainability and environmental concerns are putting pressure on natural resources, leading consumers to demand food choices that are good for them and good for the planet.

The only way to meet the needs of this growing population is through disruptive innovation. Nestlé has adopted a multifaceted approach to new ways to innovate.

Globally, the company has 23 R&D centers with 4,200 employees, tasked with discovering and developing innovative products that fuel business growth. It is adopting new ways of working, enabling the company to launch consumer-centric products more quickly. It is simplifying processes, creating a leaner organization, and funding fast-track projects. To ensure the early translation of science into groundbreaking innovations, the company is upgrading its R&D centers to include prototyping facilities and pilot-scale equipment that all its employees can use. Collaborations with suppliers and its commercial operations are being strengthened to bring new products to market faster and more efficiently.

In the first half of 2019, Nestle launched the Garden Gourmet plant-based burger, YES! snack bars in a recyclable paper wrapper, and a new range of Starbucks products. It also rolled out its infant formula with human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) across 44 markets in just 12 months. It invented the first dark chocolate made entirely from cocoa fruit for its popular KitKat brand.

Nestle recognizes the need to collaborate differently with suppliers, researchers, and start-ups. For example, strategic innovation partnerships play a key role in improving the environmental performance of our packaging. It has joined forces with Danimer Scientific partners to develop biodegradable plastic products and PureCycle to deliver the world’s first virgin-like recycled polypropylene.