From company Head in the Sand decline to Fast Follower growth: In 2012, when Hubert Joly took over as Best Buy’s CEO, the company was losing ground to Amazon and posted a huge loss. By the time Joly handed over the reins to his successor in 2019, the company was earning a profit, and its stock had soared 330%. Joly’s mindset was not to maximize profit but to create meaning for Best Buy’s employees so they would be inspired to think up and deliver its customers the best experience in the industry. This mindset drove Joly to change Best Buy’s culture, match etailers’ lower prices, partner with rivals such as Amazon, and change employee incentives to encourage them to deliver and industry-leading customer experience.

From Create the Future industry dominance to Head in the Sand irrelevance: John and George Hartford took over a small grocery store chain from their father and turned A&P into the largest grocery retailer in the United States with 16,000 grocery stores in 3,800 communities. The Hartfords were persistent experimenters – testing out different store concepts to satisfy changing consumer needs and rolling out the most effective innovations – all with greater speed and effectiveness than did competitors. They created the future of grocery retailing, and when they retired, they put their stock into a trust and appointed Ralph Burger, a long-term loyal employee, to run the company in 1951. To finance dividend payments, Burger starved investment in new retail concepts. Burger’s Head in the Sand mindset made A&P increasingly irrelevant to consumers. In 1979, A&P was sold to a German retailer, and by 2015 it went bankrupt for the second and final time after rounds of cost cutting failed to boost its revenues and cash flow.

From Create the Future leadership in one market to Create the Future leadership in others: More than any CEO discussed in this book, Amazon founder and CEO, Jeff Bezos, epitomizes the power of a CEO’s strategic mindset to create the future of previously disparate industries. Bezos’s strategic mindset rests on two ideas: his Day 1 philosophy of fighting complacency by emphasizing the importance of not relying on past approaches to solve future problems and the need to keep inventing ways to delight its easily dissatisfied and demanding consumers. Based on these two ideas and the way they changed Amazon’s strategy and operations, the company has gone from an online bookstore to a world leader in consumer ecommerce – carrying an estimated 353 million different products; operating a fast-growing logistics network; and creating and continuing to dominate the cloud services industry. Bezos’s mindset has caused Amazon to try countless experiments, measure outcomes, learn from mistakes, hire and develop talented people, and build world-class capabilities to enable Amazon to dominate the industries in which it competes.

From a Create the Future founder whose confirmation bias turns him into a Head in the Sand failure: A founder’s success can lead to failure. More specifically, the strategic mindset that enables a founder to build a successful, public company can reinforce a strong bias toward what leads to strategic success in the industry. If new technologies alter the basis of success, that founder’s strategic mindset can cause the founder to ignore the new technologies – enabling the purveyors of those innovations to take its customers. This is what happened to Digital Equipment founder and CEO Ken Olson when he dismissed the importance of the PC and the Internet. His Create the Future mindset evolved into a Head in the Sand one. Indeed, this tendency of success to lock in a founder’s initial understanding of how to compete in the industry is the reason why Bezos’s Day 1 idea is so important and powerful – if a leader can follow it.

From a Create the Future founder to a Head in the Sand successor to a Fast Follower replacement who accelerates growth: This is what happened to Microsoft when Bill Gates handed over the reins to his number two, Steve Ballmer – a Head in the Sand CEO who pushed Windows-first. Fortunately, Microsoft survived Ballmer and has done much better under his successor, Satya Nadella, a Fast Follower who changed Microsoft’s culture to put the customer first and enabled its products to work alongside competing ones had previously built Microsoft’s Azure cloud business into a formidable challenger to AWS. As of June 2020, Nadella’s nearly seven-year tenure as Microsoft CEO boosted its shares at a 29% average annual rate, leaving the company’s stock roughly four times higher than its previous peak when Bill Gates was CEO. Nadella also presided over modest revenue growth – up at an 8.3% annual rate through 2019 to $126 billion. This example makes it clear that just because he had been Gates’s number two for years, Ballmer was not best leader for Microsoft because he applied his old way of thinking to solve new problems. Nadella has proven to be more effective because he has changed Microsoft enough to apply its strengths to competing with Amazon and other more innovative rivals.1

Strategic Mindsets for Public and Pre-IPO Companies

Amazon CEO Successors: Benefits and Risks of Three Strategic Mindsets

What many of these public companies have in common is that their founders were what I call marathoners2 – founders who grow their companies from an idea to a large public company. Few of today’s marathoners have gone the distance without the help of venture capital firms. Such marathoners include Eric Yuan, CEO of Zoom Video, and Peter Gassner, founder and CEO of pharmaceutical and life sciences cloud software provider Veeva Systems. Both have proven to be adept at growing revenue, taking their companies public, and boosting their stock price. Yuan’s leadership benefited Zoom’s employees, customers, and shareholders. Between 2017 and 2020, Zoom’s revenues grew at a 117% annual rate from about $61 million to $623 million. From its April 2019 IPO and June 2020, Zoom shares soared at a 198% annual rate to $258. Gassner also did an excellent job shifting from founder to public company CEO. Between 2012 and 2020, Veeva’s revenues grew at a 43.6% annual rate from about $61 million to $1,104 million. From its October 2013 IPO to June 25, 2020, Veeva shares rose at a 29% annual rate to $236.3

CEO Skills Required at Three Stages of Scaling from Idea to Public Company

Interestingly, some successful venture capitalists are good at finding founders with the right personal traits – such as motivation, grit, passion for winning, and the ability to motivate diverse teams – needed to learn these skills as the company grows. Emergence Capital Partners’ General Partner, Santi Subotovsky, explained in a June 2020 interview, “When we assess CEOs and leaders in general we work hard to get to the bottom of their motivations as we find a high correlation between this and success. We also have the advantage of having seen leaders like Yuan and Gassner early in their journeys.” Emergence looks for CEOs who have unique personalities. “Leaders building iconic companies are typically irrationally obsessed; they have a strong conviction about how the future should work, and they don’t stop until their visions become a reality. These CEOs will work intensely to make this happen and as a result they will weather the storms that are part of the company building journeys,” noted Subotovsky. Chris Lynch, a startup investor and CEO of data virtualization provider AtScale, sees hunger and competitive drive as among the critical traits for a founder who can grow from an idea to taking a company public. As he told me in June 2020, “Fewer than 50% of company founders are still CEO when the company goes public. I have one company, artificial intelligence platform DataRobot, that has gone from $0 to $100 million in revenue with the original CEO. He is impatient with stupid questions so he would not like talking to a hedge fund analyst who owns the company’s stock. He has technical chops and vision. And he has [grit] after overcoming poverty and other challenges. He is self-aware and intensely competitive. He has leadership skills. He knows how to motivate engineering, sales, and marketing. He has the x-factor: blind ambition. He wants to build the next Google and is willing to sacrifice his personal life to get there.”4 Another venture capitalist and board member, Michael Greeley, General Partner of Flare Capital Partners, told me in July 2020, that founders who can turn an idea into a public company share unique traits. They “hear the voice of the customer – e.g., know what the customer is looking for, have the technical skills to build the product, and are pied pipers who can [attract and motivate] talent.”5

The board of directors should play a crucial role in determining the fit between the CEO and the opportunities and threats that await in a company’s future. However, if the directors do not think and act independently, the company’s investors, employees, and customers could be at risk. To avoid crimping directors’ independence, CEOs must keep their egos in check and recruit a talented board that will protect the interests of these important stakeholders by encouraging fact-based debates regarding what the company should do about its company’s opportunities and threats. Board compensation can influence whether this debate really happens. If a company pays board members nearly $600,000 a year to attend four board meetings, as Salesforce does, there is a risk that board members will refrain from asking the CEO challenging questions to preserve their seat on the money train. To counter this problem, Lynch pays directors solely in stock options. As he told me in a June 2020 interview, “This is how I pay directors. It’s a lot more work for them than public boards because the only way to make the options worth anything is to grow the company and take it public.”6

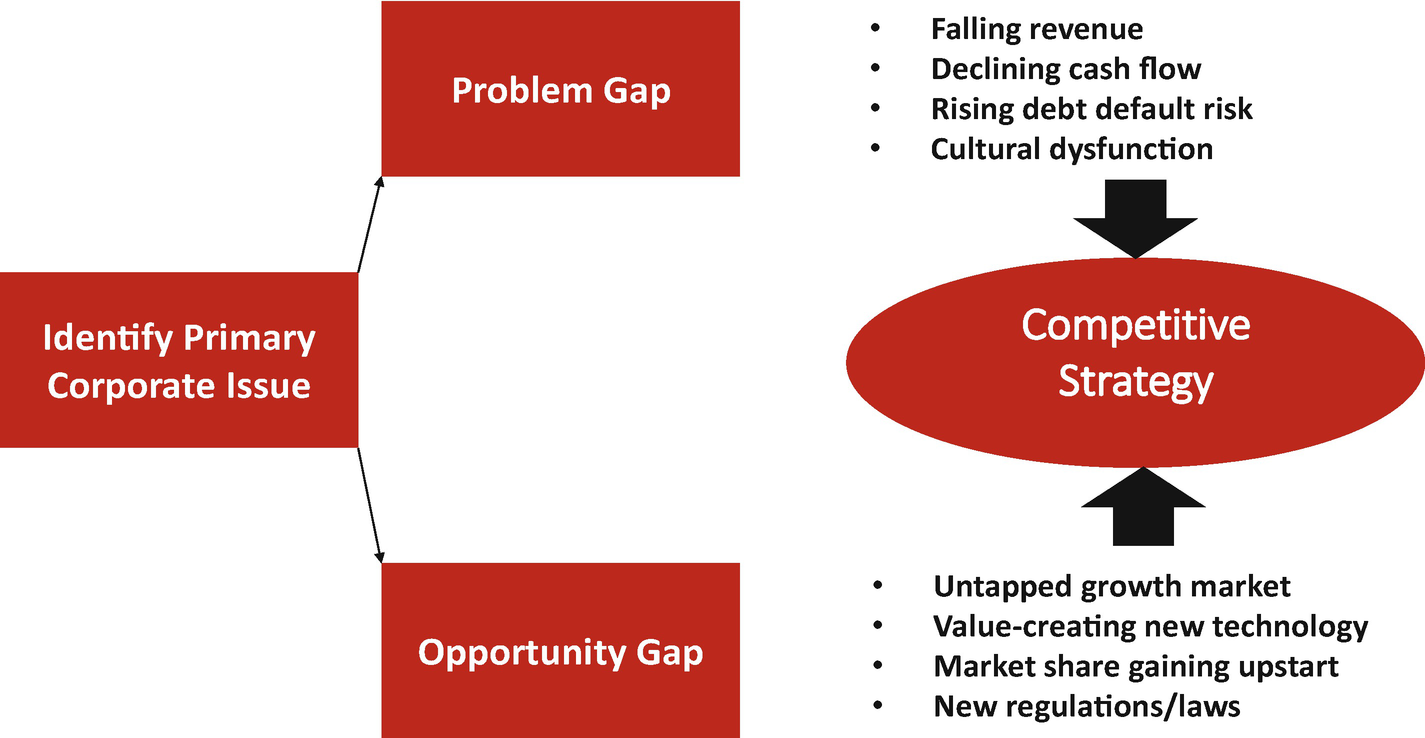

Focus the company on its most important strategic issue: That could be the risk of missing a growth opportunity or the failure to address a threat to its survival. As Harvard Business School Associate Professor, Laura Huang, said in June 2020, “Directors should start by deciding what problem the company needs to solve: opportunity gap – the company has an opportunity that it is not fully capturing – or problem gap – the company is facing a threat to its survival or market position and lacks an effective solution or has not executed it properly. Directors need to know where the company is now and where the industry is headed.”

Assess whether the CEO can hurdle each of the three stages of scaling: If a CEO cannot make it to the next stage, directors will put him in a tight spot. That is what happened to then 36-year-old Lynch six months before ArrowPoint Communications’s March 2000 IPO. The company’s lead director, venture capitalist Paul Ferri, invited Lynch to breakfast and told him to recruit the more shareholder-friendly CEO Ferri had in mind. Lynch’s “ears were burning” but he did as Ferri directed. In May 2000, Cisco acquired ArrowPoint for $5.7 billion – turning Lynch’s 1.2% stake in ArrowPoint into some $68 million worth of Cisco stock. Greeley pointed out that such decisions typically are made in conjunction with an effort to raise capital. He said, “Every 15 to 18 months, our portfolio companies need to raise capital. If they meet with 20 investors and receive no interest, it triggers a conversation with the CEO. We ask them bluntly, ‘Do you want to be rich or king?’ If they choose rich, they are more likely to be willing to step into a founder and chief technology officer role and let a new CEO take over who can raise the capital and keep the company growing.”

Encourage the CEO to execute a succession plan: Directors should encourage the CEO to develop successors. After all, at least half of company founders are no longer CEO by the time it goes public. To do that, they should hire people who have succeeded in similar companies and put them in a position where they can take on greater responsibilities. It generally works better to develop internal candidates – something that Walmart does well, according to Stanford Business School Professor Charles A. O’Reilly III. As he told me in June 2020, Succession 101 means boards should ask, “Does the [CEO candidate] have a good grasp on industry dynamics, think long-term, and drive large-scale organizational change?” To be sure, developing a successor internally helps mitigate the risk that an outside CEO will be rejected by the culture. But that cultural fit can also mean the company adapts too slowly. Walmart’s slow adoption of ecommerce is a case in point. After all, the giant retailer launched Walmart.com in 20007 and 16 years later had still not grown the business enough, so it paid $3.3 billion to acquire Jet.com as a way to hire its CEO Marc Lore8 – suggesting that sometimes an internally developed CEO is not always able to accelerate an incumbent’s growth.

Track the right performance metrics: Directors ought to monitor longer-term and short-term performance metrics. They should ask the CEO questions about trends that are significantly worse than expected – with the focus on what is causing the company to miss its numbers and what the CEO will do to get the company back on track. Those metrics will vary depending on the company’s growth stage. For public or large private companies, directors should ask the CEO to explain declining financial performance, new competitors successfully taking away market share, and new technologies that might alter the competitive landscape, said O’Reilly. Board members of a technology company that is sprinting to liquidity should focus on “development productivity, employee recruitment and retention, gross margins, customer acquisition, annual recurring revenue, customer churn and profit,” Lynch said.9

How a Change in Strategic Mindset Helps Goliath Strike Back

Changing opportunities and threats : Covid-19 abruptly changed the matrix of opportunities and threats facing Wayfair. In the latter few months of 2019 through March 2020, demand for furniture was growing only modestly. WeWork’s busted IPO resulting from its cash flow–burning business model and shareholder-unfriendly governance led investors to lose faith in the company’s ability to find a path to positive cash flow. Wayfair’s stock was plunging. Yet Covid-19 caused a feeding frenzy for furniture as millions began working from home. While stocks plunged in March 2020, investors gobbled up shares of companies that enjoyed accelerated revenue growth due to Covid-19. Between their bottom in March and June 2020, Wayfair shares soared more than eightfold.

CEO mindset : Wayfair CEO Niraj Shah’s strategic mindset was that of a Fast Follower. To Shah’s credit, he built a leading online furniture retailer by acquiring a collection of online furniture purveyors, creating a unifying furniture brand, tracking and analyzing data about consumer behavior, and expanding its product line based on the results of that analysis. Yet Shah had his limitations since Wayfair continued to suffer due to its inability to generate positive cash flow and its excessively high costs – for furniture purchasing, delivery, marketing, and servicing customers.

Competitive strategy: Wayfair’s competitive strategy did not suddenly change when Covid-19 happened. However, its competitive environment abruptly became more favorable because store-based furniture retailers were shut down due to social distancing and Amazon’s attention was distracted as it ramped up capacity to meet the surge in demand for more basic goods such as masks and hand sanitizers. Wayfair captured a large share of that surge in demand because it was already popular with consumers due to its ability to satisfy customer purchase criteria such as wide product selection, reasonable prices, and generally good service – marred slightly by flawed execution of its return policy.

Strategic Mindset and Competitive Strategy

Assessing Alignment Between Strategic Mindset, New Opportunity/Threat and Performance

A Two-Phased Approach to Leading Through Strategic Mindset

Some board members are reluctant to challenge the CEO wanting to hold onto their lucrative sinecures.

Some board members are heirs of the founders who feel entitled to dividends and lack knowledge of the company’s business.

Some board members had valuable knowledge and contacts when they joined the board – however, the industry has changed, and they have not kept up.

Board members who were appointed by the current CEO and feel uncomfortable asking the CEO for a succession plan or discussing the possibility of replacing the CEO.

To help readers assess whether their company is leading effectively through strategic mindset, what follows is an idealized version of how the board and CEO ought to interact. The value of this model is that it can help highlight where a company is falling short and help point out specific improvement opportunities as it seeks to ensure that its CEO’s strategic mindset is suited to crafting a competitive strategy that can capture opportunities and protect against threats likely to emerge in the future.

Develop a competitive strategy to close the problem/opportunity gap: As illustrated in Figure 8-5, a company’s board should heed Huang’s advice and identify the primary issue facing the company. This could be either closing the opportunity gap, for example, adopting a new technology or new business model that would enable the company to gain market share rapidly, or the problem gap, for example, reversing a slide in revenue and cash flow due to a plunge in demand resulting from social distancing. Having identified the primary corporate issue, the board would challenge the CEO – granting resources such as hiring a consulting firm or staffing a strategic planning function – to formulate options, choose a competitive strategy, and defend the strategy before the board.

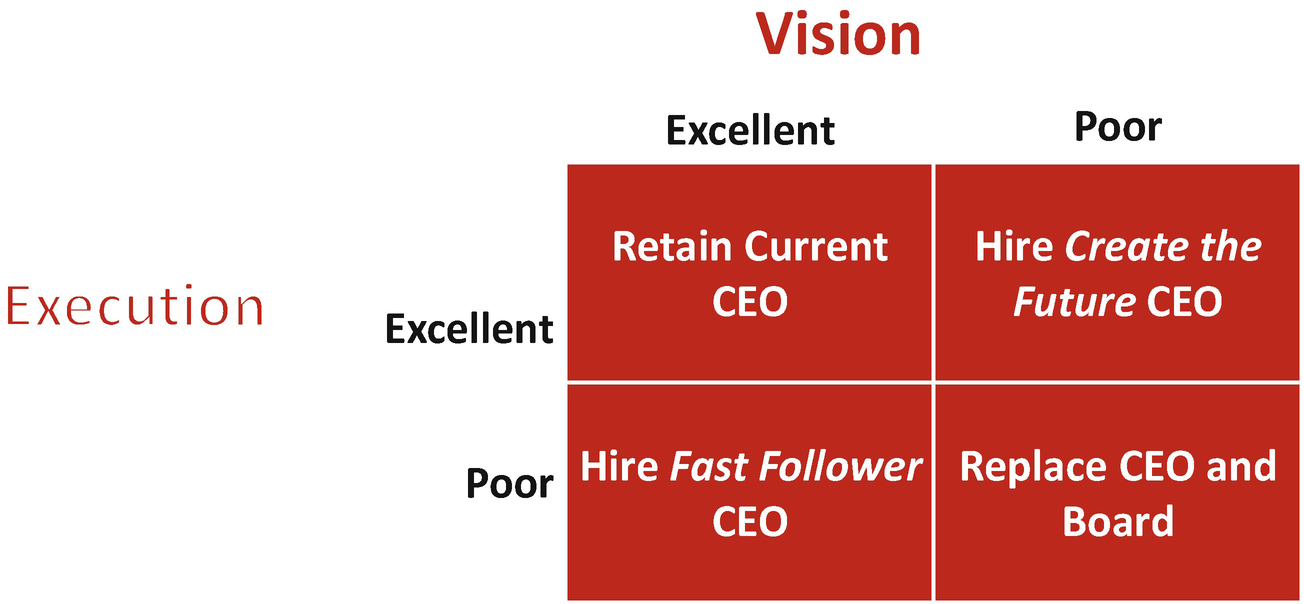

Assess the fit between the competitive strategy and CEO’s strategic mindset : As illustrated in Figure 8-6, the board would use the competitive strategy exercise to assess whether the CEO’s strategic mindset is well suited to closing the company’s problem or opportunity gap. The board should evaluate the CEO’s competitive strategy on two dimensions: the quality of the vision and the company’s ability to execute the vision. If the board determines that the vision and execution of the CEO’s competitive strategy are excellent, then the company should encourage its current CEO to implement the strategy. If the board deems the vision excellent, but the execution deficient, then the board should consider hiring a new CEO with a Fast Follower mindset – or possibly hiring a chief operating officer who can improve on and execute the strategy’s implementation plan. If the board gives a poor grade to the strategy’s vision but a high score for its execution, then the company should consider hiring or appointing a Create the Future CEO and ask the current CEO to partner with the new one as chief operating officer. Finally, if the board finds both the vision and execution of the competitive strategy to be unacceptable – or concludes that the company’s culture is dysfunctional – then the company should bring in a new CEO who has either a Create the Future or Fast Follower mindset.

Competitive Strategy to Close Problem/Opportunity Gap

Board Assessment of Competitive Strategy and CEO Strategic Mindset

Develop a Competitive Strategy to Close the Problem or Opportunity Gap

The board and the CEO should collaborate to develop a competitive strategy that closes the company’s most significant opportunity or problem gap. The relevant industry experience and regular information the CEO shares with the board should enable the board to develop a shared understanding of whether the company’s biggest issue is a problem or opportunity gap.

Closing the Problem Gap

- Declining revenues

If the company competes in different markets, are revenues dropping in all its markets? If not, which ones are suffering the biggest revenue declines?

Are revenues in those markets declining due to drop in industry demand, a cut in price, or a loss in market share?

If the company is losing market share, which competitors are gaining share and why?

Can the company take action to overtake those competitors?

- Increasingly negative cash flows

Compared to the company’s historical cash flow trends, what factors – for example, declining unit demand, lower prices, higher variable costs, or rising fixed costs – are causing cash flows to become more negative?

- Challenges in repaying debt

Does the company’s debt repayment schedule reflect the company’s most recent borrowings, bank covenants, and interest rates?

How likely is the company to continue to be able to meet its payment obligations and fulfill the terms of its debt covenants?

If the company is in near term danger of default, what is the status of negotiations with lenders?

One kind of problem gap – cultural dysfunction, for example, sexual harassment or other mistreatment of employees – would most certainly not come from scrutinizing these financial trends. The board might become aware of this class of problems through employee, partner or customer complaints about the company’s conduct. Getting to the root cause of such a problem might require the company to investigate – for example, by human resources or legal experts – possibly resulting in changing the CEO or other top executives.

While there is some risk – particularly as I write this four months after the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic – that an incumbent consumer retailer could be encountering such a problem gap, the means of closing this problem gap are conceptually straightforward, though painful to implement. For example, companies should plan to extend their cash runways by reducing cash outflows – either by selling assets or cutting staff.

Closing the Opportunity Gap

From which industries do we draw our current revenues?

- How are those industries likely to change in the future?

Are these industries growing or maturing?

Are their profit margins narrowing or widening and why?

How are new technologies, evolving customer needs, and upstart business models changing their basis of competition?

Which new industries could we enter to sustain our growth in the future?

Of these candidate industries, which ones have the most growth potential?

Why do the winners in these industries win and why do the losers lose?

What are the customer purchase criteria (CPC) that buyers use to pick among competing suppliers?

Compared to competitors, how well does the company satisfy these CPC in the minds of potential customers?

Does the company have the capabilities needed to keep winning in its current markets and attract new customers in attractive markets where it does not currently compete?

If not, can the company build or acquire these capabilities?

Can the company grow faster than its markets by adopting new technologies?

Can the company leapfrog a fast-growing competitor by offering customers more value for the price?

Can the company expand into new, growing markets in countries where it currently does not compete?

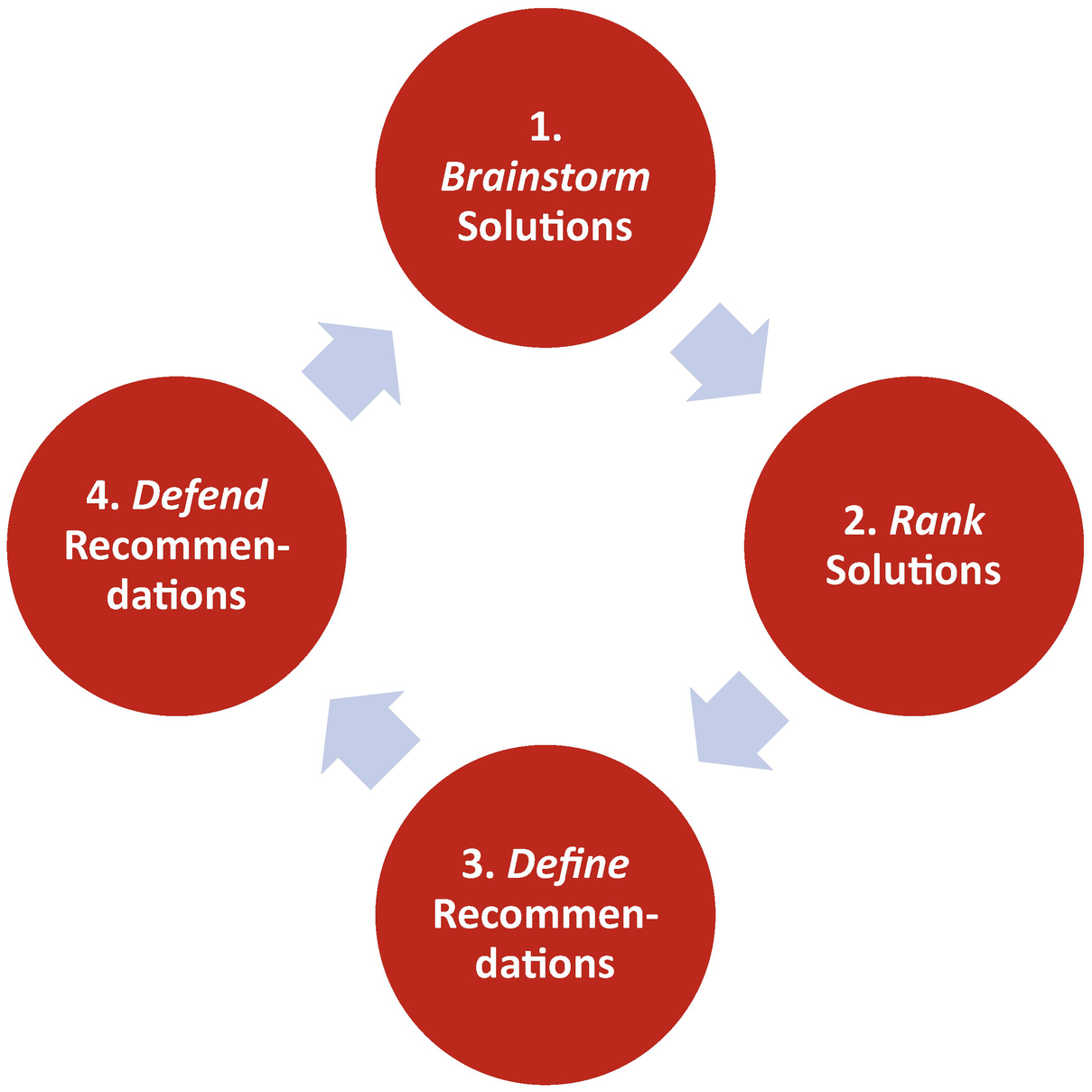

Creating a Competitive Strategy to Close the Opportunity Gap

Brainstorm Solutions

Customer group: Growth can come from winning more customers from within the company’s current target market segment or from a new segment. For example, a business that sells to banks and insurers could grow by selling to more of them or by selling to another segment – such as media and entertainment or retailing.

Geography: Companies can seek additional growth from customers in their current geographies or from new ones. Often companies that have saturated growth opportunities in the United States, for example, will seek to gain market share in China or India.

Product: In addition, companies can grow by developing new products internally or acquiring companies and training their salesforces to sell the acquired company’s products.

Capabilities : Companies can grow by using their current capabilities to attack new markets or developing new capabilities which will enable them to tackle those new markets. Netflix developed new capabilities – most notably it produced its own programs and cut its DVD delivery service way back – when it switched from its DVD-by-Mail service to online streaming.

Culture: Of the five dimensions of growth, culture is the most intangible. However, it is worth noting that some companies have cultures that encourage growth more effectively than others. For example, companies that hire and reward people who care about creating value for customers, who think independently, and who collaborate well with other teams and people outside the company tend to grow faster than other cultures.

Rank Solutions

Market attractiveness: When comparing options, strategists should gather data on the attractiveness – for example, the size in dollars, growth rate, and average profitability – of the market or markets from which revenues will flow.

Competitive advantage: In addition, strategists should estimate how much each option will increase the company’s market share and why. If the company does not currently have a share of the relevant market, the strategy team should make that clear and provide their forecast of how much market share the company can gain in the next five years. The strategy team should also describe why potential customers are likely to prefer the company’s product over those of competitors.

Net present value : Net present value is based on forecasting future cash flows over, say, the next years, discounting them into current dollars, and subtracting off the investment required to implement the option. In the issue table, the strategy team should compare the options on the investment required and the NPV.

Define Recommendations

Arenas: Here, leaders articulate which products they intend to offer to which customer groups as well as how they will distribute the products and in which countries.

Vehicles: Vehicles describe how a company will implement its strategy – either by developing new products, partnering with others, or acquisition.

Value proposition: The value proposition articulates why customers will buy the company’s product – by specifying how the company’s product prevails over competitors on the customer purchase criteria.

Staging: Staging refers to the sequence of actions the company must undertake to implement the strategy. Staging can be articulated in an implementation plan which lists the actions, accountable managers, deadline, as well as the costs and benefits for each action.

Economic logic : The economic logic describes how the company will earn a profit – either as a low-cost producer, setting the lowest price in the industry, or differentiator, charging the industry’s the highest price.

Defend Recommendations

Why is the recommendation’s target market attractive? The strategy team should reiterate the market’s size, growth rate, and profitability and explain the factors driving the growth and future profitability of the industries where they are recommending that the company compete.

Why will the recommendation boost the company’s market share? The strategy team should reiterate the company’s current market share and explain how the recommendation will boost its forecast for the company’s market share in five years. The strategy team should also explain why the recommendation will enable the company to prevail over rivals on the most important CPC. Finally, the strategy team should explain the critical activities needed to win on these criteria and why the recommendation will enable the company to prevail on each activity.

Why will the recommendation generate a positive NPV? Here the strategy team should articulate the key assumptions they used in their NPV calculation, including how they calculated the investment required, present their base case NPV, and articulate the robustness of the NPV by describing a sensitivity analysis in which the NPV is recalculated after reducing each of the key assumptions by 10%.

Assess the Fit Between the CEO’s Strategic Mindset and the Competitive Strategy

Will the current CEO’s mindset impel or impede the company’s ability to grow faster?

If not, what criteria should the board use to select a new CEO?

What strategy guidelines should the board give the company’s next CEO?

To gain insight into the first question, the board can use the framework outlined in Figure 8-6. If the vision and execution of the CEO’s recommendations are sound, the board should seek to retain the current CEO; if the vision is good and the execution needs improvement or vice versa, the board should hire an executive to help bolster the CEO’s weaknesses; and if both are poor, the board should replace the CEO. To some extent, the board can assess these questions by evaluating how well the competitive strategy answers the questions outlined in the previous paragraphs on how to create a competitive strategy.

Assessing CEO’s Vision

Assessing CEO’s Execution

Growth trajectory : Based on customer feedback and analysis of competitor strategies, the board can evaluate whether the company is solving a problem that customers perceive as painful; whether its solution to the problem offers more benefits for the price than do competing products; and whether the company has a compelling set of future growth vectors – for example, customer groups, geographies, and products in which it will invest to achieve continued growth.

Growth capital raising: For a publicly traded company – unless it is suffering severe cash flow problems – raising growth capital is less time-consuming than for a startup. To persuade the board to allocate capital to implement the growth trajectory, the CEO must make a fact-based case that the vision will enable the company to gain a large enough share of large new market opportunities to earn an attractive return on the deployed capital.

Culture of growth: To attract and motivate the top-rate talent required to achieve the desired revenue growth, the CEO must create a culture of growth. The key elements of such a culture are a corporate mission that attracts talent and a set of action-backed values that motivate the talent to listen to customers and respond to their evolving needs by providing them products that industry-prevailing value to customers.

Redefining job functions : A company must employ people with the skills needed to perform the critical activities required to execute it. For example, if an incumbent retailer decides to boost its online revenues, it must employ a team that can deploy the technology and business processes needed to purchase a wide variety of inventories, display the options to consumers visiting online or via an app, enable customers to place their orders, fulfill the orders accurately and on time, and respond to customer questions to assure that they are satisfied. One test of a CEO’s ability to execute their vision is whether these functions are clearly defined in the company’s organization structure.

Hiring, promoting, and letting people go: With the aid of a clearly defined and widely understood growth culture, a CEO ought to make sure that the best possible talent occupies the roles redefined to enable the company to execute the vision. Along with filling these critical jobs with the best talent, the CEO must attract new talent to fill roles left open by promotions and departures of those who do not fit with the company’s culture or cannot do the work required of them.

Holding people accountable: With the right people in the right jobs, the CEO must hold them accountable for achieving specific business objectives for their functions that will, when aggregated, enable the company to grow faster and realize the CEO’s vision. To do that, people in each function ought to set their own goals – in coordination with the leadership team – to assure that everyone in the company is “rowing” toward the same goal. Setting the right goals and tracking their achievement will strengthen the execution of the CEO’s vision.

Coordinating processes : To avoid wasting effort in pursuit of these goals and boost efficiency of execution, the company ought to set up processes – such as new product development, order fulfillment, and customer success – that cut across functions. Such coordination can help avoid missteps and reduce the number of repeated steps performed by different functions. Coordinating the processes can also enable the company to become aware of and adapt more quickly to unpleasant surprises.

By assessing the vision and execution of the CEO’s competitive strategy in this way, the board can assess whether the current CEO’s strategic mindset fits what the company needs for future success. If the board determines that the CEO’s competitive strategy will close the problem or opportunity gap and that the vision and its execution are strong, then the CEO’s strategic mindset is a good fit. If the board concludes that the CEO’s competitive strategy does not close the problem or opportunity gap, then a new CEO should be hired – and the board will likely need to decide whether to pick a successor with a Create the Future or Fast Follower mindset to come up with a better strategy. If the board concludes that the competitive strategy is sound – but the CEO’s vision or execution is weak, then the board might consider bringing in a co-CEO or chief operating officer with a mindset that complements the current CEO.

Conclusion

For decades, a dominant narrative in business has been the feisty upstart knocking down the lumbering giant. The idea behind this story was that all the resources the large incumbents controlled were impeding their ability to sense changes in customer needs, develop or deploy new technology, and invent new business models that customers would find more compelling. Through the 18 case studies of Create the Future, Fast Follower, and Head in the Sand strategic mindsets, we have seen that this David vs. Goliath narrative is not immutable. Indeed, in some of the book’s case studies – such as Best Buy in consumer electronics, The New York Times in news, and Walmart in groceries – a Fast Follower mindset was able to overcome a Goliath’s inherent inertia and mobilize the company’s strengths into a much stronger competitive position that spurred faster revenue growth, happier employees, more satisfied customers, and richer shareholders. By engaging in a fact-based dialogue over strategy and execution between the CEO and an independent board, a company can assure that there is a tight fit between the strategic mindset of the CEO and the competitive strategy needed to close the company’s opportunity or problem gap.