CHAPTER 5: THE SEVEN ENABLERS OF COBIT 5

‘All our dreams can come true – if we have the courage to pursue them.’

Walt Disney (1901-1966)

The seven COBIT 5 enablers were outlined in Chapter 4 under Principle 4: Enabling a holistic approach where it was made clear that enablers need to work together if governance is to be achieved. This chapter discusses each of the seven categories of enablers in depth.

First of all, each enabler is expressed in terms of two concepts:

• Enabler Dimension

• Enabler Performance Management

Enabler Dimension

The word ‘dimension’ is used considerably by COBIT 5:

• Process Dimension

• Capability Dimension

• Enabler Dimension

Dimension is best understood as meaning ‘aspects’ or ‘set of elements’.

Process Dimension covers the aspects of every COBIT 5 process in terms of their names, their purpose and their practices and so on.

The Capability Dimension covers the aspects of the Process Assessment Model (PAM) needed for assessing the capability of every process in terms of capability levels (0 to 5) and process attributes (PA) used to assess each level. This will be covered in Chapter 9.

Enabler Dimension covers aspects of every enabler and these aspects are:

• stakeholders,

• goals,

• lifecycle,

• good practices.

Stakeholders

Stakeholders are any people, internal to the enterprise or external, who are involved with, or have an interest in, the enabler. Examples of stakeholders are shown in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1: Examples of Enabler Stakeholders

| Internal Stakeholders | External Stakeholders |

| Board of Directors | Shareholders |

| CEO, CFO, CIO, CRO, CISO, COO, CTO | Customers |

| Business executives, managers and business process owners | Business partners and suppliers |

| Risk and compliance managers | Regulators and standardisation bodies |

| Security managers | Consultants |

| Service managers | External auditors |

| Internal auditors | |

| IT managers | |

| IT users |

It is the stakeholders’ needs that drive the enterprise goals that themselves determine the IT-related goals needed by the enterprise.

Goals

Enablers provide value to the enterprise by the achievement of goals. Each enabler goal is described in terms of three categories, as shown in Table 5.2.

Table 5.2: Enabler-goal Categories

| Enabler category | Meaning |

| Intrinsic quality | Enabler works accurately and objectively providing reputable, accurate and objective results. |

| Contextual quality | Enabler is fit for purpose (i.e. displays relevance and effectiveness) in the context in which it is used. This means it will be understandable, easy to use and it will work and achieve outcomes completely, appropriately and consistently. |

| Access and Security | Enabler and its outcomes are accessible as required but also secured so that enabler outcomes are only accessible to those people who need and have been granted access. |

Lifecycle

Each of the enablers has a lifecycle that starts with planning the introduction of the enabler, followed by operationally using it and then eventually disposing of it at the end of its lifetime. COBIT 5 provides a standard list of lifecycle phases, as shown in Table 5.3.

Table 5.3: Enabler Lifecycle Phases

| Lifecycle phases |

| Plan |

| Design |

| Build/Acquire/Create/Implement |

| Use/Operate |

| Evaluate/Monitor |

| Update/Dispose |

Good Practices

Each of the enablers needs to be defined in terms of the good practices it will use. COBIT 5 provides the good practices that should be used for some enablers such as Processes and Information – in the COBIT 5: Enabling Processes and the COBIT 5: Enabling Information manuals. For other enablers, guidance is provided from other standards, frameworks and academic research. For example, the good practices for the Culture, Ethics and Behaviour enabler is largely based on Kotter’s (1996) textbook Leading Change.

Enabler Performance Management

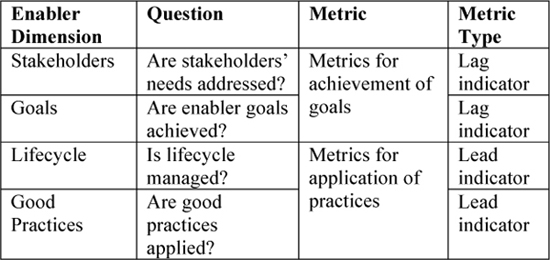

Performance of enablers is managed in COBIT 5 through the assessment of each of the four enabler dimensions: stakeholders, goals, lifecycle and good practices.

Assessment is simply conducted by asking a question to determine whether each enabler dimension has been achieved and specifying metrics that can be used to measure the extent of the achievement, as shown in Table 5.4.

Table 5.4: Enabler Performance Management: Questions and Metrics

Metrics that measure how successfully lifecycle management is taking place and how well good practices are being applied do not indicate that desired outcomes are being achieved, but they are likely to indicate that enablers are being successfully run, which is likely to lead to the desired stakeholder needs and enterprise goals being achieved. However, only measurement of the achievement of stakeholder needs and enterprise goals will actually indicate that is the case.

A good analogy for lead and lag indicators is the relationship between appraisals given by delegates at the end of a COBIT 5 training course and the exam results achieved by delegates. The trainer will look at the course appraisal sheets and if these are all very positive about the course then that will be a lead indicator to the trainer that the delegate pass rate on the COBIT 5 exam will be high. However, only on receipt of the COBIT 5 exam results (the lag indicator) will the delegate pass rate be known.

Enablers 1 - 7

Enabler 1: Principles, Policies and Frameworks

Principles are the governance body’s expression of its fundamental values and assumptions that it uses to express its views concerning the beliefs of the enterprise and the directions it has intentions of driving to. Principles are used to communicate both internally and externally and to ensure sound stewardship of assets that belong to the shareholders of a commercial enterprise or citizens of a public sector enterprise. Principles can be viewed as an expansion of the mission and vision statements of an enterprise. Example documents that cover principles are: ethics charter and social responsibility charter. A social responsibility charter was devised by the World Bank as a document that stated: ‘The commitment of business to contribute to sustainable economic development – working with employees, their families, the local community and society at large to improve the quality of life, in ways that are both good for business and good for development.’ Principles should be brief and simple.

Based on principles, governance bodies provide policies to management to formally convey what has to be accomplished by management – that is, the policies are the rules and guidance on the overall intention and direction.

Frameworks are governance and management frameworks that ensure proper governance and management of enterprise IT by the provision of structure, guidance and tools. COBIT 5 is such a framework, of course. Policies need to be a part of the overall governance and management framework that itself is the structure into which all policies fit and links to the underlying principles of the enterprise.

Key points

Stakeholders:

Stakeholders define policies (internal stakeholders in governance roles) and comply with policies (internal and external stakeholders).

Goals:

Principles should be limited in number and written in simple language to communicate the enterprise values.

Policies need to be effective, efficient and non-intrusive. Non-intrusive is a specialist term that means that anyone who is expected to comply with a policy understands the reasoning in the policy and therefore is unlikely to resist conformance to a policy. It is important to ensure policies are readily available to stakeholders.

Frameworks need to be open, comprehensive and flexible such that changes to the enterprise’s situation can be readily dealt with. The frameworks should be current in that they deal with the current governance direction and objectives. They also need to be available to all stakeholders.

Lifecycle:

Policies have a lifecycle and need a strong policy framework. This is vital to ensure that, for example, regulatory compliance by internal controls is met. A policy framework enables policy documentation to be structured into groupings and categories that make it easier for employees to find and understand the contents of policies. Policy frameworks can also be used to help in the planning and development of the policies for an organisation.

Good Practices:

As already stated, principles should be brief and simple.

Policies need to be explained in terms of their scope and validity and they should be revised regularly. It is vital to ensure mechanisms for the checking and measuring of compliance with policies are in place and that exceptions to policies can be handled using defined consequences for any stakeholder failing to obey policies; otherwise it is pointless having policies. Policies also need to meet the enterprise’s risk appetite. A good source of policy statements is governance and management frameworks such as COBIT 5.

Enabler 2: Processes

Processes – meaning the 37 processes of COBIT 5 – is the most important enabler in most people’s view. However, it is vital to recognise that implementing processes alone will not be totally effective. Other enablers are certainly needed as well – particularly the Culture, Ethics and Behaviour enabler that is needed to recognise why processes should be run and how they should be dealt with to manage and govern the enterprise. There have been many published examples over the past 20 years of enterprises formally introducing processes (e.g. ITIL and PRINCE2/PMBOK®) without ensuring culture changes are also put in place, and as a consequence the processes have not been highly effective at improving the running of the enterprise. In addition, the People, Skills and Competencies enabler is vital for ensuring process owners, managers and practitioners have the necessary ability to deal with processes.

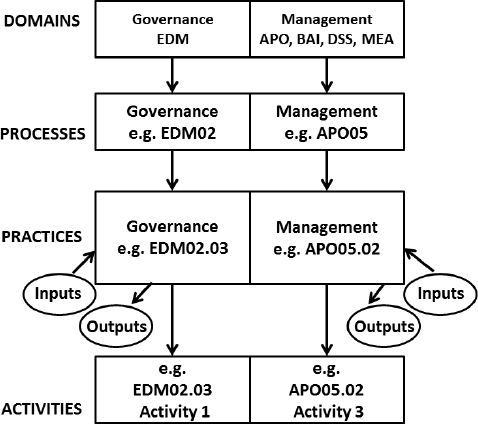

COBIT 5 defines a process as ‘a collection of practices influenced by the enterprise’s policies and procedures that takes inputs from a number of sources (including other processes), manipulates the inputs and produces outputs (e.g. products and services).’ This is a common style of definition for a process, although it is interesting to note that, in detail, inside each COBIT 5 process, it is specifically the management and governance practices of each process that accept the inputs and deliver the outputs (see Figure 5.1).

There are 37 COBIT processes and these are summarised in the Process Reference Model (see Appendix B).

Key Points

Stakeholders

Stakeholders are internal and external and cover a wide range of roles. Specifically, COBIT 5 processes each provide a RACI chart for 26 roles split into business and technology (Table 5.5).

Table 5.5: Process Stakeholders

| Business | IT |

| Board | CIO |

| CEO | Head Architect |

| CFO | Head Development |

| COO | Head IT Operations |

| Business Executives | Head IT Administration |

| Business Process Owners | Service Manager |

| Strategy Executive Committee | Information Security Manager |

| Steering (Programme/Projects) Committee |

Business Continuity Manager |

| Project Management Office | Privacy Officer |

| Value Management Office | |

| Chief Risk Officer | |

| Chief Information Security Officer | |

| Architecture Board | |

| Enterprise Risk Committee | |

| Head Human Resources | |

| Compliance | |

| Audit |

Goals

Each process in the COBIT 5: Enabling Processes manual describes process goals with metrics that enable measurement of the achievement of goals. However, under the ISO/IEC 15504 Information Technology: Process Assessment Standard that COBIT 5 uses for process assessment, the formal COBIT 5 Process Reference Model (PRM) has to use the terminology ‘outcomes’ instead of ‘process goals’. Therefore, although the COBIT 5: Enabling Processes manual provides ‘process goals and metrics’ for each process, the PRM used for process assessment (in the COBIT 5: Process Assessment Model (PAM): Using COBIT 5 manual) refers to these as ‘outcomes’. They are word-for-word identical.

Process Goals are enabler goals and are, therefore, part of the COBIT 5 Goals Cascade (see Chapter 4).

Process goals should be intrinsic in that they conform to good practice – in particular, they are accurate and comply with internal and external rules. Processes should always be adopted and adapted as required to meet the enterprise’s needs so that they are relevant and understandable; meaning they can be readily applied in the enterprise – that is, they meet contextual goals. If required, processes may be made confidential with controlled access – that is, they meet accessibility and security goals.

Lifecycle

To define, operate, monitor and optimise processes all steps of the generic Lifecycle should be used (see Table 5.3).

Good Practices

COBIT 5 processes are based on established best practices as discussed in Chapter 2.

Processes are arranged in domains and each process consists of practices with inputs and outputs. The details of a practice are defined as activities (Figure 5.1). The terminology used here is that used in the COBIT 5: Enabling Processes manual.

Figure 5.1: COBIT®5 Process Structure

Enabler 3: Organisational Structures

This enabler is quite simplistic and describes key factors to take into account when structuring organisational units that relate to all levels of governance and management activities.

Key Points

Stakeholders

Internal and external stakeholders may be used and they have various roles that include decision making, influencing and advising that relates to clients, suppliers, risks, audits and so on.

Goals

The goals for organisational structures are to have well-defined operating principles linked to other good practices that are mandatory for the enterprise to adopt.

Lifecycle

Organisational structures need to be planned, designed and created, operated, optimised and eventually disbanded when no longer required.

Good Practices

The good practices needed here are well established across most enterprises already, but to summarise they are:

• The operating principles, particularly staffing roles, frequency of meetings and documentation.

• The composition in terms of internal and external stakeholders that make up each organisational structural unit.

• Where decisions can be made in parts of the organisation – that is, how many staff are controlled by a manager. The term used by COBIT 5 is ‘span of control’.

• Across which parts of the enterprise including processes does a person have control? The term used by COBIT 5 is ‘level of authority/decision rights’. Permitted delegation of activities – that is, delegation of authority.

• The escalation structure and procedures for dealing with issues raised that can’t be resolved normally. The term used by COBIT 5 is ‘escalation procedures’.

Enabler 4: Culture, Ethics and Behaviour

Key Points

Stakeholders

Particular stakeholders for this enabler are those responsible for defining, implementing and enforcing desired behaviours in terms of rules and norms. Roles include: HR managers, risk managers, compliance managers, legal staff, and boards and panels such as promotion boards and remuneration and awards panels.

Goals

Goals are concerned with:

• Organisational ethics based on the desired enterprise values expressed in its principles.

• Personal ethics based on a person’s life and feelings: for example, social background, religion, ethnicity, where they live, views they have adopted (e.g. green environment, human rights) or are forced to adopt based on their role (e.g. a membership organisation’s professional ethics)72.

• Individual behaviours that include ethics collectively make up the enterprise’s culture. Individual behaviours encompass personal ambitions, but interpersonal relations and willingness to obey enterprise policies are equally important. Particularly important behaviours relate to the enterprise’s appetite for risk and the way the enterprise deals with negative outcomes. Clearly, good practice is to learn from negative outcomes and make improvements rather than blaming individuals for their behaviour.

Lifecycle

Lifecycles are needed to introduce good practices for culture, ethics and behaviour. The key activities needed are listed under good practices.

Good practices

Recognised good practices that assist the introduction and ongoing adoption of desired culture, ethics and behaviour include:

• Regular communication throughout the enterprise to encourage stakeholders to keep in place the desired behaviours and fully recognise corporate values.

• Raising awareness of desired behaviours by the exemplary behaviours demonstrated by senior managers and champions (both IT and business people).

• Encouragement of desired behaviours by the use of incentives and deterrents. Incentives include HR reward schemes. Deterrents will be the fact that contracts of employment or engagement formally state expected behaviours and staff are, therefore, aware of the consequences of disobedience such as verbal or written warnings leading to loss of employment or cessation of contracts.

• Rules and norms that are detailed guidance on behaviours to ensure adherence to policies.

Enabler 5: Information

It is well recognised in the modern world of computer-based information and knowledge that computers store data (just a bit pattern meaning, for example, the number 621) which is transformed and understood as information (e.g. the hotel room number you have been allocated). Information is transformed into knowledge from the experience of the use of information by many people (e.g. that a room with number 621 is likely to be on the 6th floor of a hotel, which may be unsuitable for someone with a fear of heights). It is business processes that use IT processes to generate and process data, which can then be transformed into information and knowledge.

Key Points

Stakeholders

All stakeholders are involved with information: information producers create information while information custodians store and maintain information. Others, called information consumers, only use information.

Goals

• Intrinsic quality of information is the amount of conformance with values. Is the information accurate (correct and reliable), objective (unbiased), believable (true and credible) and reputable (source is genuine or content is sound)?

• Contextual quality of information is its applicability and relevance to the user’s tasks in that it is clearly and intelligibly presented. Key terms that COBIT 5 uses to describe the contextual quality of information are: relevancy, completeness, currency, appropriate amounts of information, concise and consistent representation, interpretability, understandability and ease of manipulation. Here is an example to show what these terms mean. Information is your personal credit card statement. It needs to be relevant in that it is for your company credit card only, not for all the staff in your company with company credit cards. It is complete in that it includes all transactions and it is current in that it covers only the past month. It will have appropriate amounts of information so you can identify the date, amount and company that the transactions were with. The statement will be concise and consistent in that it fits on just one or two pages and the format is the same every month and is always in your language and currency so that you can interpret and understand the meanings and amounts of transactions. Ease of manipulation would mean the included figures in the statement made it clear what the monthly automated or mandatory payment amount would be and the date that it will happen, as well as the remaining amount with the date that needed to be paid to avoid interest and the amount of interest charged if the remaining amount is not paid by that date. Security and accessibility means information is available or obtainable when required and can be rapidly and readily retrieved. Access is restricted to authorised parties.

Lifecycle

The generic lifecycle applies as usual.

Important points to recognise are:

• Plan is the phase where information architectures and standards such as data definitions are prepared.

• Build/Acquire includes purchasing and access to external data sources as well as the creation of data records.

• Use/Operate includes store, share and use. Store is the phase where information is held in electronic form as files, databases or data warehouses, in hardcopy form or even in human memory! Share is the phase in which information is distributed and includes e-mailing messages, providing a website or a fileserver and so on. Use is the phase where information is used. Obvious examples include: raising alert messages as pop-ups on a screen and/or as e-mail messages; updating of real-time statistics such as departure and arrival times of airline flights; and converting dollars into euros when changing money at a bank.

Best practice

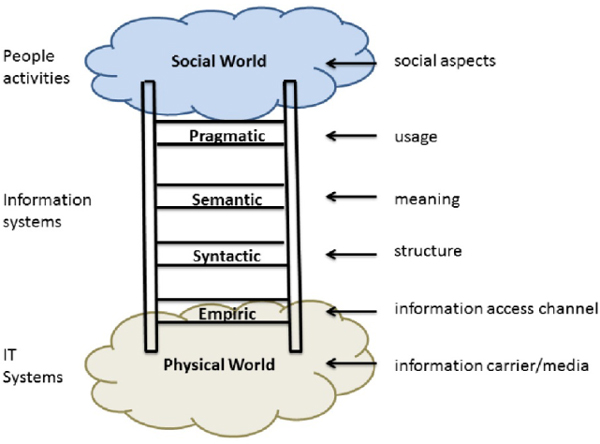

As discussed in Chapter 2, ISACA put in place an information model to deal with the significant increase in information and the need not only to manage information but also to select appropriate information to make effective business decisions. COBIT 5 therefore uses information systems theory (a major growth area in the past decade) and employs the well-established Semiotic Framework, which COBIT 5 uses as part of the COBIT 5 Information Model.

Here is a discussion of the background and origin to this theory.

Semiotics

A popular definition of semiotics is ‘the study of signs’ and it is concerned with the creation, representation and interpretation of signs. John Locke in 1690 stated that physics, ethics and semiotics were the three branches of human knowledge.

So what has a sign to do with information? Well, as de Saussure said in 1916: ‘A sign consists of a signifier which is the form a sign takes and a signified which is the concept it represents.’ (For example, © is the form of a sign for the concept of copyright.) Stamper73 said that ‘all information is carried or represented by signs.’ For example, a network data packet is a sign, as is a business case document and a JavaScript™ program. So, signs consist of the form information takes and the concept it represents.

Why do information systems need to use signs? Stamper, in 1973, recognised that descriptions of information are ‘extremely fuzzy’ and a simple logical system is needed if information is to be carefully defined using standard technical terms so that a scientific approach to the creation and development of information systems theory could be established. He realised that he could extend Morris’ (1938) basic semiotic model to completely cover all levels of information. Let’s first of all look briefly at Morris’ semiotic model of signs.

Morris’ Semiotic Model

Morris’ semiotic model of signs had three levels:

• Syntactics, that is, structure

• Semantics, that is, meaning

• Pragmatics, that is, usage

This is the case for any sign. For example, © is the structure, copyright is the meaning and the usage is to place it on the colophon page (frontispiece) of a published book to remind readers about the copyright laws that apply.

Semiotics Framework (or Semiotics Ladder)

Here is a diagram (Figure 5.2) based on Stamper’s Semiotic Ladder.

Figure 5.2: Semiotic Ladder. (After Beynon-Davies (2009)74 and Stamper (1996)75.)

Stamper recognised he needed to add Empiric and Physical levels so that information theory introduced by Shannon76 in 1948 was incorporated, that is, the physics of signs that is the hardware used to transmit, receive and process them and the empirics of signs which covers patterns, variety, noise, channel capacity, codes and so on. The ladder from Physical World to Social World covers data (Empiric and Syntactic) and information (Semantic and Pragmatic) that becomes knowledge in the Social World. The Physical World is where everything that can be empirically observed takes place. Information structures at the Pragmatic level is used to construct Social World activities such as creation and agreement of contracts, interpretation of a business case or management decision making based on balanced scorecard reports.

Examples of the layers are:

Physical world: Radio wave signals (Wi-Fi), square wave voltages on Ethernet cables, writing on paper or even 9000BC rock carvings at Cave of the Beasts, Wadi Sura in the Western Desert in Egypt.

Empiric: Wi-Fi channels, user interfaces.

Syntactic: Grammar rules such as subject verb object – for example, the dog jumped the fence, or programming language structures, for example, IF (X .GT. 5) GO TO 10077.

Semantic: The meaning of information. For example, what does ‘stone’ mean? Google and other search engines just think it means those five letters and finds everything including archaeological websites about Stonehenge, geological websites about rocks as well as websites about the rock groups The Rolling Stones and The Stone Roses! The semantic web, researched and developed by Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the World Wide Web, organises information by the meaning of stone. The semantic web approach is beginning to be used by search engines such as Google Knowledge Graphs, which searches for actual information about the subject of your query rather than just a list of links. Try typing Madonna into Google to see the Google Knowledge Graph result on the right-hand side of the page. COBIT 5 sees the meanings of the semantic layer as information type (e.g. personal or public), information currency (i.e. past, present or future) and information level (e.g. the different structure of daily, weekly and monthly reports from a Service Desk).

Pragmatic: The use of information that covers the structures and rules to be used. An example would be the format of a business case document with standardised headings and content together with the format that includes the date, author and version page at the front. COBIT 5 specifies: retention period, information status (e.g. current or historical), novelty (is it creative information or confirmation of existing information) and contingency (other information that this information needs as its source).

Social World: Is where information is used. Obvious examples of formal information are courts of law and religious services, but the presentation by physicists at CERN of experimental results in the search for the Higgs Boson needed to use very formal statistical graphs of their experimental results to convince the audience the results confirmed the presence of the Higgs Boson. The structure of the wall on your Facebook page is a Social World too, but it is not normally a key social world for enterprises using COBIT 5!

Enabler 6: Services, Infrastructure and Applications

IT services deliver outcomes to businesses. IT services are constructed of infrastructure and applications. Infrastructure is hardware (e.g. servers, routers, desktops, laptops, cables etc.), operating systems and facilities (buildings and power, air conditioning etc. for data centres). COBIT 5 uses the term service capabilities to mean the combination of services, infrastructure and applications.

Key Points

Stakeholders

Stakeholders deliver and use services. Delivery of services will be conducted by internal and external stakeholders since, in addition to an internal IT department, suppliers of some sort are always used (e.g. telcos, and operating system suppliers). In the case where extensive outsourcing is used there will still be internal stakeholders who manage the suppliers (e.g. the CIO and a small team). Users will be internal business users and external clients, partners and suppliers.

Goals

Goals that need to be met are provision of infrastructure and applications to create and run services. Services require an understanding of stakeholder needs in order to define service levels in service level agreements (SLAs) and deliver these.

Lifecycle

The Plan and Design steps of the lifecycle are where a target architecture is planned and designed for future services, infrastructure and applications. Architectures move from baseline architecture (i.e. existing architecture) via transition architectures (if needed) to target architecture. Transition architectures will be used when the timeframe for target architecture is long and intermediate stages are required.

Good practices

Enterprise architecture is the good practice and it provides overall guidance (via architecture principles) for governance of all implementation and use of IT-related resources.

Key enterprise architecture principles:

• The enterprise architecture should be as simple as possible yet must meet the enterprise’s requirements, and that also means it must be agile to meet the changing needs of the enterprise.

• The enterprise architecture should use open industry standards, for example, TOGAF®, CEAF or FEA (see Chapter 2) for the enterprise architecture and ITIL for IT service management.

• Ensure components of the architecture can be reused when transition or target architectures are being designed.

• Purchase IT solutions rather than building an enterprise’s own IT solutions in circumstances where that is possible and enterprise policies grant external purchase permission. Since enterprises’ requirements in the modern era are changing regularly and new applications and hardware are constantly emerging from suppliers, it is less effort to purchase rather than update or rewrite internal applications.

Enabler 7: People, Skills and Competencies

Clearly, to deliver any of the other enablers an enterprise needs people with appropriate skills and competencies.

Key Points

Stakeholders

Both internal and external people are stakeholders and every role will have a need for specific skills and competencies.

Goals

In this enabler, goals are the required skills and competencies together with the need to have required numbers of people and a desirable turnover rate – that is, not too high.

Lifecycle

The generic lifecycle applies to this enabler, of course, but the key parts are to understand the levels of skills required for roles and the numbers of people for each role. To meet the required skill levels people will need to be trained and/or skilled people recruited or suppliers used to conduct the roles. Periodically, it is essential to re-evaluate the required skills and competencies and this leads to training, external recruitment or use of appropriately skilled providers. As years go by some skills and competencies are no longer required and so people who do not have the desire to transform their skills will need to be made redundant.

Good practices

Required good practices are to define the roles in terms of skills and competencies and that is often conducted by the creation of formal job descriptions. However, a more detailed understanding of IT skills levels can be expressed in terms of skills categories (e.g. as required by 1st, 2nd and 3rd-line incident management practitioners). This has been particularly well expressed by the Skills Framework for the Information Age (SFIA78), initially created in 2003 and continually updated, currently at SFIA 5. The SFIA Foundation, the owner of SFIA, states that ‘SFIA defines 96 professional IT skills, organised in six categories, each of which has several subcategories. It also defines seven levels of attainment, each of which is described in generic, non-technical terms.’

_______________

72 For example: ISACA® members’ code of professional ethics.

73 Stamper, R. K. (1973), Information in Business and Administrative Systems, London, Batsford.

74 Beynon-Davies, P. (2009), Business Information Systems, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan.

75 Stamper, R. (1996) ‘Signs, information, norms and systems’ in Signs of Work: Semiosis and Information Processing in Organisations, (Ed. Holmquist, B., et al.), Berlin, de Gruyter.

76 Shannon, C.E. (1948), ‘A Mathematical Theory of Communication’, The Bell Systems Technical Journal, 27, pp. 379–423, 623–656. Available at http://cm.bell-labs.com/cm/ms/what/shannonday/shannon1948.pdf (Accessed 5 September 2013).

77 A FORTRAN program statement.

78 www.sfia-online.org/v501/en/publications/reference-guide/at_download/file.pdf