Chapter 12

Project Procurement Management

According to the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition, “Project Procurement Management includes the processes to purchase or acquire the products, services, or results needed from outside the project team to perform the work,” as well as the contract management and change control processes to administer any contract issued by authorized project team members, by the performing organization (normally the seller), or the outside organization (normally the buyer).

In government projects, the performing organization can be the responsible government agency, because its employees are often the most directly involved in doing the work of the project. However, for certain projects known as “turnkey” projects (e.g., design-build-operate-transfer), the seller would be the performing organization—and the government the outside organization—because the seller is the enterprise whose employees are most directly involved in doing the work of the project (see Section 12.2).

Governments around the world invest enormous amounts of money in project procurement. In the United States alone, government procurement in the construction industry amounted to $230 billion in 2004. To estimate the total government project procurement, one must also add government procurement in other countries and expand to other industries, such as health and human services, aerospace, defense, environmental, financial, oil, gas, petroleum, utilities, and communications technologies.

This enormous magnitude of government procurement presents significant challenges in achieving efficiency, integrity, and equity in government procurement. Meeting these challenges is essential to achieving the efficient use of government resources, to maintain the public trust, and to ensure open and fair competition among prospective government contractors (hereafter referred to as “sellers”). To be effective, Project Procurement Management must be institutionalized within the organization. A first step is to have government procurement decisions made by government officials who are accountable to the public through procurement regulations, protest procedures, conflict of interest laws, and other similar provisions. Another step is to encourage sellers to recognize the integral roles of their organizations in meeting these challenges.

Hence, Project Procurement Management should serve the following purposes:

- Provide an open, fair, and competitive process that minimizes opportunities for corruption and that assures the impartial selection of a seller

- Avoid potential and actual conflicts of interest, or the appearance of a conflict of interest

- Establish an objective basis for seller selection

- Obtain the best value in terms of price and quality

- Document the requirements that a seller must meet in order to obtain payment

- Provide a basis for evaluating and overseeing the work of the seller

- Allow flexible arrangements for obtaining products and services given the particular circumstances, provided such arrangements do not violate the other purposes of Project Procurement Management.

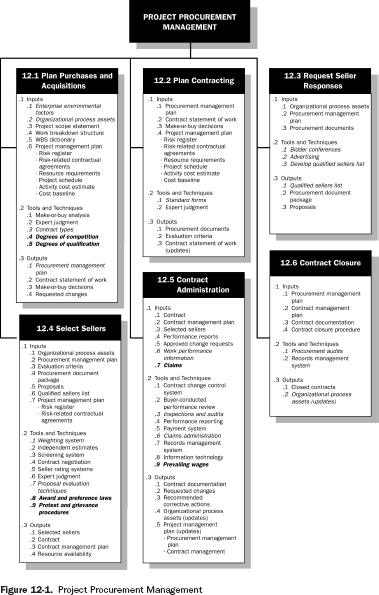

The PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition describes six processes under the Project Procurement Management Knowledge Area:

- 12.1 Plan Purchases and Acquisitions

- 12.2 Plan Contracting

- 12.3 Request Seller Responses

- 12.4 Select Sellers

- 12.5 Contract Administration

- 12.6 Contract Closure

12.1 Plan Purchases and Acquisitions

See Section 12.1 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

12.1.1 Plan Purchases and Acquisitions: Inputs

Section 12.1.1 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition discusses inputs to Plan Purchases and Acquisitions. Although all of these inputs apply in government procurement of projects, the first two of these categories should also include additional inputs that apply especially to procurement in public sector projects:

- .1 Enterprise Environmental Factors

Enterprise environmental factors (Section 4.1.1.3) that are considered in most projects include the conditions of the marketplace and what products, services, and results are available in the marketplace, from whom, and under what terms and conditions. On government projects, certain marketplace conditions may differ from those in the private sector. For example, some sellers target specific market sectors (e.g., consumer, commercial, etc.) and position themselves to meet the needs of those sectors. As a result, there may be fewer sellers that are both capable and willing to contract with the government.

If the performing organization does not have formal purchasing and contracting groups, then the project team will have to supply both the resources and the expertise to perform project procurement activities. On government projects, the government generally acts as the performing organization, and has formal purchasing and contracting groups that perform procurement activities, including the awarding of contracts to outside organizations.

- .2 Organizational Process Assets

Organizational process assets (Section 4.1.1.4) provide the formal and informal procurement-related policies, procedures, guidelines, and management systems that are considered in developing the procurement management plan and selecting the contract types to be used. Organizational policies frequently constrain procurement decisions. These policy constraints can include limiting the use of purchase orders and requiring all purchases above a certain amount to use a longer form of contract, requiring specific forms of contracts, limiting the ability to make specific make-or-buy decisions, and limiting or requiring specific types or sizes of sellers.

In government procurement, most constraints are formal rules established by the controlling representative body. These constraints can also include requiring advertising of contract opportunities prior to their award, sealed bids or proposals from sellers, and open public bids or proposals. These constraints are typically comprised of the following:- An open, fair, and competitive process for selecting and awarding contracted services. An open, fair, and competitive process is designed to ensure that the project obtains the best value, to prevent collusion and corruption, and to afford an opportunity to all responsible sellers.

- The evaluation method and basis of award published in advance. Publishing the method to be used to evaluate sellers and the basis of award to the selected seller establishes a level playing field.

- The level of funding authorized by the representative body. The funding authorized by the representative body may not be exceeded without an additional appropriation by the representative body.

- Programs to achieve social and economic goals. These programs can include preferences for disadvantaged population groups and preferences for small businesses.

Organizations in some application areas also have an established multi-tier supplier system of selected and pre-qualified sellers to reduce the number of direct sellers to the organization and establish an extended supply system. In government procurement, establishing a supplier system can include competitive selection of a seller as the primary supplier for a certain category of products or services. However, if the value of the project is above a certain amount, the seller may still be required to compete with other potential sellers. In each of these competitions, utilization of a pre-qualification procedure is intended to attract better qualified sellers.

12.1.2 Plan Purchases and Acquisitions: Tools and Techniques

Section 12.1.2 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition discusses three tools and techniques for Plan Purchases and Acquisitions. In the third of these, Contract Types, several additional tools have particular application on government projects. Two other categories of government project-specific tools and techniques are also added: Degrees of Competition and Degrees of Qualification:

- .3 Contract Types

See Section 12.1.2.3 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition, which discusses three broad categories of contract types. There are other important contract types used in government projects, as discussed below:- Indefinite delivery indefinite quantity contracts (IDIQ). Some agencies also call these “job-order,” “on call,” or “standby” contracts. The contract typically states the type of service to be delivered, the length of time (generally five years or less) during which services can be requested from the seller, and the minimum and maximum of the contract amount. Additionally, the contract typically includes a “price book.” Each potential seller submits a markup or markdown in the form of a coefficient (e.g., 1.1 or 0.9). Many agencies utilize this method of obtaining services for small projects. Seller selection is a time-consuming process. To go through this process for each project is often inefficient and may cause unacceptable delays. IDIQ increases efficiency and minimizes delay by performing the selection process once for many projects. In many cases, the IDIQ contract is in place before the start of a project. With the contract in place, a project manager for the government can obtain the necessary services without having to go through a separate solicitation process. This streamlined process supports small, non-complex projects.

- Unit price contract. Unit price contracts are a special category of fixed price contract. Unit prices are ideally based on standard units of measurement (e.g., man-hour, linear foot, cubic meter). A unit price contract typically states estimated quantities and fixed prices for each unit of work. Many agencies use this type of contract for projects where the actual quantities of work may vary from the estimated quantities.

- Multiple award schedules. Multiple award schedules can be used when there is a generally accepted “reasonable price” for a good or service. Multiple award schedules are particularly valuable for procurement of commodities. Each potential seller submits its qualifications and schedule of rates to the government procurement office. Assuming each schedule of rates is based on generally accepted “reasonable” prices. The government procurement office can select the seller that is most advantageous to the government. If these are approved, government agencies may buy goods and services at the published rates without a separate competition. In many jurisdictions, this type of contract is fairly new and often requires specific legislation because of the long-term nature of the relationship. This method is often adopted as a strategic sourcing initiative and supported by W. Edwards Deming’s fourth point for management, “End the practice of awarding business on the basis of price tag. Instead, minimize total cost. Move toward a single supplier for any one item, on a long-term relationship of loyalty and trust.”

- .4 Degrees of Competition

- Full and open competition. All responsible sources are allowed to compete. This is the most commonly used contracting approach in government procurement.

- Other than full and open competition. Some government agencies exclude one or more sellers from competing. Depending on the scenario, the degree of competition can range from a group of sellers to a single seller. Common scenarios are discussed below:

(a) Set-aside. A set-aside for small businesses or disadvantaged firms is an example of this method. Alternatively, a government agency may establish minimum targets or “goals” for participation by small businesses and disadvantaged firms, which the seller must demonstrate good faith efforts to achieve. Another example is that some procurement opportunities are open to international sellers; others are restricted to national companies.

(b) Sole-source. A “sole-source” contract is used where permissible by law when there is only a single seller that can perform the work—by reason of experience, possession of specialized facilities, or technical competence—in a time frame required by the government. This type of contract requires a written justification to be approved by an authorized government official.

(c) Eminent domain. Eminent domain has been in use for thousands of years, and is probably the oldest form of government procurement under established legal systems (e.g., Roman law, the Magna Carta, the Code Napoleon, and the Constitution of the United States. The government may take possession of private property when this action is in the best interest of the public. Eminent domain is used most often to take possession of real property. The government is generally required to pay just (i.e., fair) compensation for the property.

- .5 Degrees of Qualification

All government contracts require that the seller meet minimum qualifications listed in the procurement documents. Assuming these minimum qualifications are met, the degree of qualification depends on the basis of selection. There are some common approaches:- Lowest responsible seller. This approach is the most common basis for selection in government procurement. Potential sellers’ bids or proposals are evaluated to ensure that they meet minimum qualifications. Then, the cost proposals of the qualified sellers are reviewed and the lowest responsible seller is selected. For example, in a construction contract, the minimum qualifications are generally a contractor’s license, liability insurance, and a payment and performance bond. However, the minimum qualifications may vary. For example, minimum qualifications may also include financial solvency, a satisfactory safety record, and successful performance on comparable projects.

- Best value based on price and qualifications. Sellers’ bids or proposals are evaluated to ensure that they meet minimum qualifications. Then, the technical and cost proposals of the qualified sellers are reviewed. Sellers are evaluated by a combination of several factors including price and qualifications, with a predetermined weight assigned to each factor. A weight may be assigned to the price as part of the weighted sum, or the unweighted price may be divided by the weighted sum of other factors to determine the cost per point. The contract is then awarded to the seller that has the highest weighted score or lowest cost per point, whichever is applicable. This is also known as a best value selection.

- Qualifications-based selection. This basis of selection is most often used on contracts for professional services. Price is generally not a factor in selection of professional services during project planning and design because the cost of such services is a small fraction of the project’s implementation cost. For example, increased quality in the planning and design of a building can result in large savings via the cost of construction of the building. Sellers’ qualifications are evaluated, the sellers are ranked, and a contract is negotiated with the best qualified firm. If the government and the seller are unable to agree on a reasonable price, the government terminates the negotiations and begins negotiating with the second-ranked firm, etc.

12.1.3 Plan Purchases and Acquisitions: Outputs

- .1 Procurement Management Plan

Section 12.1.3.1 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition says “The procurement management plan describes how the procurement processes will be managed from developing procurement documentation through contract closure.” In government procurement, a major driver is the applicable set of procurement laws, rules, and regulations. Hence, the procurement management plan should reference the requirements of any applicable laws, rules and regulations. The PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition lists the following elements of a procurement management plan, to which has been added another element: “Constraints and Assumptions”:- Types of contracts to be used

- Who will prepare independent estimates and if they are needed as evaluation criteria

- Those actions the project management team can take on its own, if the performing organization has a procurement, contracting, or purchasing department

- Standardized procurement documents, if they are needed

- Managing multiple providers

- Coordinating procurement with other project aspects, such as scheduling and performance reporting

- Handling the lead times required to purchase or acquire items from sellers and coordinating them with the project schedule development

- Handling the make-or-buy decisions and linking them into the Activity Resource Estimating and Schedule Development processes

- Setting the scheduled dates in each contract for the contract deliverables and coordinating with the schedule development and control processes

- Identifying performance bonds or insurance contracts to mitigate some forms of project risk

- Establishing the form and format to be used for the contract statement of work

- Identifying pre-qualified selected sellers, if any, to be used

- Procurement metrics to be used to manage contracts and evaluate sellers.

- Constraints and assumptions that could affect planned purchases and acquisitions. Examples of constraints include: Whether and to what extent advertising of the contracting opportunity is required and the selection process to be used including the basis of award.

A procurement management plan can be formal or informal, can be detailed or broadly framed, and is based upon the needs of the project. The procurement management plan is a subsidiary component of the project management plan (Section 4.3).

- .2 Contract Statement of Work

See Section 12.1.3.2 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

- .3 Make-or-Buy Decisions

See Section 12.1.3.3 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

- .4 Requested Changes

See Section 12.1.3.4 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

12.2 Plan Contracting

See Section 12.2 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

12.2.1 Plan Contracting: Inputs

See Section 12.2.1 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

12.2.2 Plan Contracting: Tools and Techniques

- .1 Standard Forms

Standard forms include standard contracts, standard descriptions of procurement items, non-disclosure agreements, proposal evaluation criteria checklists, and standardized versions of all parts of the needed bid documents. Organizations that perform substantial amounts of procurement can have these documents standardized. Buyer and seller organizations performing intellectual property transactions should ensure that non-disclosures are approved and accepted before sharing any project-specific intellectual property with the other party.

In government procurement, the government often acts as the buyer and utilizes standard forms for bid documents (e.g., bid or proposal forms, bid bonds, payment and performance bonds) as well as other contract documents (e.g., general conditions, certificates of insurance, specifications) to ensure that the bid from each seller is based on the same terms and conditions.

- .2 Expert Judgment

See Section 12.2.2.2 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

12.2.3 Plan Contracting: Outputs

See Section 12.2.3 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

12.3 Request Seller Responses

The Request Seller Responses process obtains responses, such as bids and proposals, from prospective sellers, normally at no cost to the project or buyer. In government procurement, there may be a relatively small cost to the project or buyer if a “stipend” is paid to one or more unsuccessful proposers to acquire rights to their technical proposals.

12.3.1 Request Seller Responses: Inputs

See Section 12.3.1 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

12.3.2 Request Seller Responses: Tools and Techniques

Section 12.3.2 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition discusses tools and techniques for Request Seller Responses. These have particular application in government procurement, and the following information should be considered, in addition to what is provided in the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition:

- .1 Bidder Conferences

In government procurement, bidder conferences are one of several types of permissible communications with potential sellers. Subject to prequalification by a government agency (see Section 12.3.2.3), all potential sellers are given equal standing during this initial buyer and seller interaction to produce the best bid, quote, or proposal. Communications between potential sellers and government officials are strictly controlled from the date a procurement document is issued until a seller is selected and a contract is awarded. The manner of communications is set forth in the procurement documents. Permissible communication consists of:- Meetings or conferences. These meetings or conferences (also called contractor conferences, vendor conferences, and pre-bid conferences) are meetings with potential sellers prior to the preparation of a bid, quote, offer, or proposal. Such meetings are typically used to ensure that all potential sellers have a clear understanding of key information about the procurement (e.g., project, contract requirements, and the bidding process). A meeting or conference can be held in varied formats, such as face-to-face or via the Internet. A meeting or conference is often made a mandatory requirement to ensure that potential sellers make responsive bids. If a meeting or conference is held, the entire proceeding is normally scripted to ensure that key information is correctly understood by each of the potential sellers. If questions received during a meeting or conference are not covered by the prepared script, the questions and their corresponding answers are generally documented in writing.

- Written procurement communications. The government agency may issue communications, to respond to questions or inquiries from potential sellers, or to clarify procurement documents. Such communications are generally documented in writing, incorporated into the procurement documents, and distributed to all potential sellers who have provided an address for the receipt of such communications.

- On-site inspection tours. A site visit may be held by the government to provide the potential sellers with a clear understanding of the site issues relating to procurement. Any statements by the government agency are documented in the same way as other responses to questions from potential sellers.

- .2 Advertising

Existing lists of potential sellers can often be expanded by placing advertisements in general circulation publications such as newspapers, or in specialty publications such as professional journals. Some government jurisdictions require public advertising of certain types of procurement initiatives, and most government jurisdictions require public advertising of pending government contracts. Such public advertising names the project and describes the contracting opportunity. For certain categories of projects (e.g., public works), the government requires advertisements to be published in general and/or trade publications circulated in the locality of the project. Many governments also publish a bulletin that lists all their contracts that are in the solicitation process. These include the Commerce Business Daily (United States government), Government Gazette (many governments), California Contracts Register, and similar publications.

- .3 Develop Qualified Sellers List

Qualified sellers lists can be developed from the organizational assets if such lists or information are readily available. Whether or not that data is available, the project team can also develop its own sources. General information is widely available through the Internet, library directories, relevant local associations, trade catalogs, and similar sources. Detailed information on specific sources can require more extensive effort, such as site visits or contact with previous customers. Procurement documents (Section 12.2.3.1) can also be sent to determine if some or all of the prospective sellers have an interest in becoming a qualified potential seller.

In government procurement, there are several degrees of qualification (as described in Section 12.1.2.5 of this extension). To be considered a qualified seller by the government agency, a potential seller must have at least the minimum qualifications to perform the work of the project. This is also called seller responsibility. There are several methods of determining seller responsibility including prequalification of potential sellers. A government official may or may not elect to pre-qualify sellers. If the government elects to pre-qualify sellers, it may be required to advertise the contracting opportunity for contracts above a certain value and invite all responsible sellers to submit appropriate qualifications documents (e.g., pre-qualification questionnaire, statement of financial condition, statement of qualifications) in advance of a seller’s proposal or quotation. A list of pre-qualified sellers can be developed for use on a specific project or developed on an annual basis for use on multiple projects. If a seller is pre-qualified for a specific project, the seller is not necessarily pre-qualified for general use.

12.3.3 Request Seller Responses: Outputs

Section 12.3.3 of PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition covers three outputs of the Request Seller Responses process. In the first of these, some additional information is relevant to government procurement:

- .1 Qualified Sellers List

The qualified sellers list is comprised of those sellers who are asked to submit a proposal or quotation. In government procurement, the government is required to invite all qualified responsible sellers to submit a proposal or quotation for contracts above a certain value. Such an invitation normally takes the form of advertising (Section 12.3.2.2), but may also include additional outreach efforts. If the government pre-qualifies sellers, the qualified sellers list would consist of only the pre-qualified sellers (Section 12.3.2.3). However, if the government does not pre-qualify sellers, the qualified sellers list would comprise only potential sellers whose qualifications are yet to be determined until after receipt of their qualifications documents. Thus, governments may ask sellers to submit a proposal or quotation before determining whether those sellers are qualified.

- .2 Procurement Document Package

See Section 12.3.3.2 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

- .3 Proposals

See Section 12.3.3.3 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

12.4 Select Sellers

See Section 12.4 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

12.4.1 Select Sellers: Inputs

See Section 12.4.1 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

12.4.2 Select Sellers: Tools and Techniques

Section 12.4.2 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition discusses seven tools and techniques for the Select Sellers process, which have varied application in government project procurement. Some comments—as well as two new tools—with special relevance to government projects have been added below:

- .1 Weighting System

A weighting system is a method of quantifying qualitative data to minimize the effect of personal prejudice on seller selection. Most such systems involve assigning a numerical weight to each of the evaluation criteria, rating the prospective sellers on each criterion, multiplying the weight by the rating, and adding the resultant products to compute the overall score.

In government procurement, a weighting system is often set forth in the procurement documents, including the relative importance of each evaluation criterion.1 When the basis of award is best value, the evaluation criteria includes price and other factors (e.g., experience, quality, financial condition) to determine the seller’s proposal that is most advantageous to the government. If price is given a weight, the overall score is determined as described above. Alternatively, a technical score may be computed based on all criteria excluding price, after which price is divided by the technical score to determine the overall score. In this way, the highest ranked seller will be the seller having the lowest price per technical point, and debate on the relative importance of price can be avoided.

- .2 Independent Estimates

See Section 12.4.2.2 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

- .3 Screening System

See Section 12.4.2.3 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

- .4 Contract Negotiation

In government procurement, many government jurisdictions do not allow negotiation of contracts that are above a certain value.

Instead, government jurisdictions generally require submittal of firm proposals that can be evaluated without negotiation and may be accepted or rejected. If selection is based on best value, most government jurisdictions limit the scope of negotiation to the seller’s technical proposal, unless the category of work is professional services. After separate negotiations with each seller, which are limited to discussion of its technical proposal, sellers may be invited to submit a revised proposal representing the seller’s best and final offer (see also Section 12.4.2.4 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition).

- .5 Seller Rating Systems

See Section 12.4.2.5 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

- .6 Expert Judgment

See Section 12.4.2.6 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

- .7 Proposal Evaluation Techniques

In government procurement, potential sellers submit sealed proposals that are opened publicly at a pre-established time and location. A seller’s proposal is rejected if it is late or non-responsive. A proposal is non-responsive if it includes qualifications or conditions, is not submitted in the required format, or is not accompanied by the required documents (e.g., bid security). Governments also reserve the right to reject all proposals received, and proposals become the property of the government. Potential sellers whose proposals are not accepted are notified in writing after the selection of the successful seller.

When demonstrations or oral presentations (also known as interviews) are a part of the process, government may elect to make them either mandatory or optional. In such an interview, each potential seller presents the contents of its proposal and clarifies or explains any unusual or significant elements it includes. Potential sellers are not allowed to alter or amend their proposals after submission. Neither are potential sellers allowed to conduct negotiations during the interview process. A “best business practice” calls for each panelist to prepare his or her list of questions so that the same questions are asked of each potential seller (see also Section 12.4.2.7 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition).

- .8 Award and Preference Laws

Representative bodies often use preferences in procurement to achieve social and economic goals. Preferences may be a percentage target or “goal,” or an absolute restriction. Some examples of preferences include:- Geographic preference. In some government jurisdictions, a local seller has preference over a non-local seller. This preference may be applied by a national government giving preference to its own nationals or by a regional or local government, giving preference to regional or local firms. However, national governments that are signatories to the WTO Agreement on Government Procurement and the provincial governments within such nations may not discriminate against foreign or non-resident sellers by establishing preferences.

- Population groups. Many governments give a preference to a particular population group as a form of affirmative action. A preference may be in the form of a set aside or minimum target or goal for participation. These population groups may be minorities, other people who are deemed to be disadvantaged (e.g., women and disabled people), or people to whom the voters feel indebted (e.g., military veterans).

- Small businesses. Many governments give a preference to small businesses to foster growth in the economy.

- .9 Protest and Grievance Procedures

Each governing body has administrative procedures for sellers to file grievances and protests related to an award. In summary, the seller identifies each issue in a written communication to the government agency. After reviewing those issues, the government agency sends a written response to the seller. If the response from the agency does not satisfy the firm, an informal meeting or formal hearing is scheduled. However, final decisions are the agency’s responsibility. The seller must exhaust the administrative process before proceeding through the court system.

12.4.3 Select Sellers: Outputs

See Section 12.4.3 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

12.5 Contract Administration

See Section 12.5 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

12.5.1 Contract Administration: Inputs

Section 12.5.1 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition discusses six inputs to the process of Contract Administration. One of these inputs requires information unique to government procurement, and a seventh input has been added with special application to government projects:

- .1 Contract

See Section 12.5.1.1 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

- .2 Contract Management Plan

See Section 12.5.1.2 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

- .3 Selected Sellers

See Section 12.5.1.3 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

- .4 Performance Reports

See Section 12.5.1.4 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

- .5 Approved Change Requests

See Section 12.5.1.5 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

- .6 Work Performance Information

In government procurement, the seller submits invoices or requests for payment on a periodic basis (e.g., monthly) as specified in the contract. Most government agencies are subject to “prompt payment” laws or regulations that require payment of the undisputed amount of an invoice in a prompt manner (see also Section 12.5.1.6 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition).

- .7 Claims

If the government agency rejects a contract change requested by the contractor, this rejection can potentially lead to the filing of a claim by the seller. A rejected contract change request is also known as a potential claim. The project manager is responsible for attempting the early resolution of disputes before they become actual claims.

12.5.2 Contract Administration: Tools and Techniques

Section 12.5.2 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition discusses tools and techniques for Contract Administration. Comments have been added to two of these, relative to government procurement. Also, one additional tool is shown, with particular public sector application.

- .1 Contract Change Control System

See Section 12.5.2.1 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

- .2 Buyer-Conducted Performance Review

See Section 12.5.2.2 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

- .3 Inspections and Audits

Depending on the type of contract, there are various inspection clauses. The government retains the right to inspect project deliverables for compliance to requirements prior to acceptance. The responsible agency has a duty to the voters and taxpayers to ensure that it has received the contracted goods and services, and that these goods and services meet the specifications.

- .4 Performance Reporting

See Section 12.5.2.4 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

- .5 Payment System

See Section 12.5.2.5 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

- .6 Claims Administration

In government procurement, a government agency generally has a structured dispute resolution process for unresolved claims. However, the process of dispute resolution can require up to several years before a final resolution (see also Section 12.5.2.6 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition).

- .7 Records Management System

See Section 12.5.2.7 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

- .8 Information Technology

See Section 12.5.2.8 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

- .9 Prevailing Wages

Some governments require that sellers on a public works project pay their employees the prevailing wage at the geographic location of the project. In many government jurisdictions, prevailing wage is defined as the “modal” average. When so defined, the prevailing wage represents the wage paid to the largest number of people in the job classification in the geographic area. However, the prevailing wage may also be defined as the average of the wages paid to all people in the job classification. The principle of the prevailing wage requirement is to level the playing field between sellers. Each seller can seek to lower costs through managing the project more efficiently, rather than simply cutting the wages of its employees.

12.5.3 Contract Administration: Outputs

See Section 12.5.3 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

12.6 Contract Closure

See Section 12.6 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

12.6.1 Contract Closure: Inputs

See Section 12.6.1 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

12.6.2 Contract Closure: Tools and Techniques

Section 12.6.2 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition discusses two tools and techniques for Contract Closure. Comments have been added to these, relative to government procurement. Also, a third tool has been added, with particular application to the public sector.

- .1 Procurement Audits

As stated in the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition, “A procurement audit is a structured review of the procurement process from the Plan Purchases and Acquisitions process (Section 12.1) through Contract Administration (Section 12.5). The objective of a procurement audit is to identify successes and failures that warrant recognition in the preparation or administration of other procurement contracts on the project, or on other projects within the performing organization.”

In government procurement, a procurement audit would also address the following:- Utilization compliance review (e.g., small business)

- Compliance with government policies review (e.g., competitive selection).

- .2 Records Management System

See Section 12.6.2.2 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

- .3 De-Obligation of Funds

In government procurement, contract closure also allows the government agency to de-obligate any remaining funds (and redirect funds to other contracts for the approved project) and, where appropriate, return funds to the fund source. De-obligation of funds is also known as un-encumbering of funds.

12.6.3 Contract Closure: Outputs

Section 12.6.3 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition discusses outputs for Contract Closure, all of which apply to government projects. Two new aspects that have particular application in government projects have been added:

- .1 Closed Contracts

See Section 12.6.3.1 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.

- .2 Organizational Process Assets (Updates)

See also Section 12.6.3.2 of the PMBOK® Guide—Third Edition.- Utilization compliance reports. A final utilization report of population groups and small businesses (see Section 12.4.2.8) is prepared by sellers and submitted to the government agency for use in tabulating statistics for the government agency as a whole.

- Policies compliance report. Other reports may be prepared by a government agency regarding compliance with government policies and procedures for transmittal to the funding agency, and a narrative description of lessons learned, if any, for future use in similar projects.