Surviving Disruption

by Maxwell Wessel and Clayton M. Christensen

DISRUPTIVE INNOVATIONS ARE LIKE MISSILES launched at your business. For 20 years we’ve described missile after missile that took aim and annihilated its target: Napster, Amazon, and the Apple Store devastated Tower Records and Musicland; tiny, underpowered personal computers grew to replace minicomputers and mainframes; digital photography made film practically obsolete.

And all along we’ve prescribed a single response to ensure that when the dust settles, you’ll still have a viable business: Develop a disruption of your own before it’s too late to reap the rewards of participation in new, high-growth markets—as Procter & Gamble did with Swiffer, Dow Corning with Xiameter, and Apple with the iPod, iTunes, the iPad, and (most spectacularly) the iPhone. That prescription is, if anything, even more imperative in an increasingly volatile world.

But it is also incomplete.

Disruption is less a single event than a process that plays out over time, sometimes quickly and completely, but other times slowly and incompletely. More than a century after the invention of air transport, cargo ships still crisscross the globe. More than 40 years after Southwest Airlines went public, tens of thousands of passengers fly daily with legacy carriers. A generation after the introduction of the VCR, box-office receipts are still an enormous component of film revenues. Managers must not only disrupt themselves but also consider the fate of their legacy operations, for which decades or more of profitability may lie ahead.

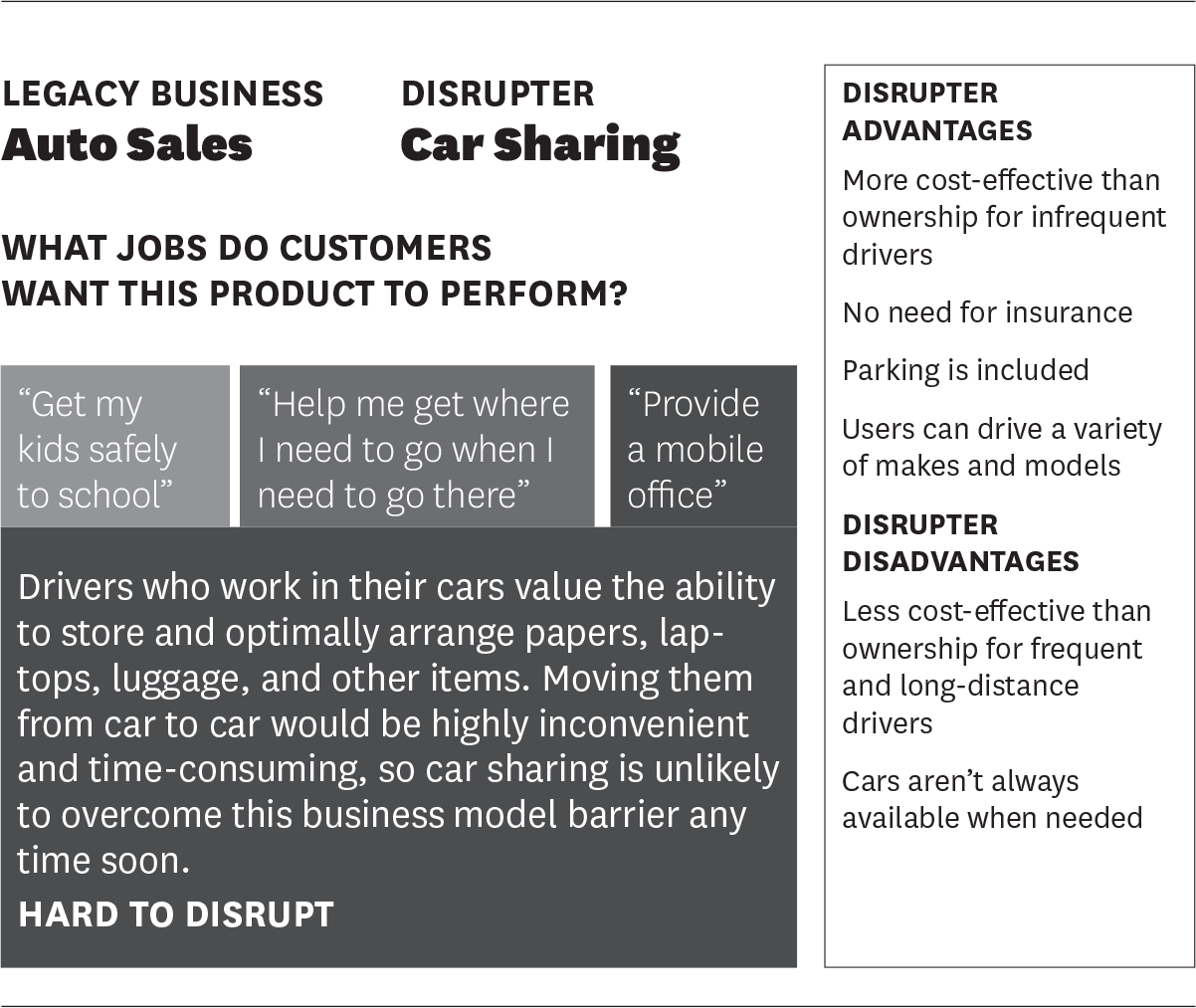

We propose a systematic way to chart the path and pace of disruption so that you can fashion a more complete strategic response. To determine whether a missile will hit you dead-on, graze you, or pass you altogether, you need to:

Identify the strengths of your disrupter’s business model

Identify your own relative advantages

Evaluate the conditions that would help or hinder the disrupter from co-opting your current advantages in the future

To guide you in determining a disrupter’s strengths, we introduce the concept of the extendable core—the aspect of its business model that allows the disrupter to maintain its performance advantage as it creeps upmarket in search of more and more customers. We then explore how a deep understanding of what jobs people want your company to do for them—and what jobs the disrupter could do better with its extendable core—will give you a clearer picture of your relative advantage. We go on to delineate the barriers a disrupter would need to overcome to undermine you in the future. This approach will enable you to see which parts of your current business are most vulnerable to disruption and—just as important—which parts you can defend.

Where Advantage Lies

What makes an innovation disruptive? As our colleague Michael Raynor suggested in his book The Innovator’s Manifesto (2011), all disruptive innovations stem from technological or business model advantages that can scale as disruptive businesses move upmarket in search of more-demanding customers. These advantages are what enable the extendable core; they differentiate disruption from mere price competition.

To understand this important distinction, consider Raynor’s example of simple price competition in the hotel industry: A Holiday Inn provides a bed for the night for less (and in less luxury) than does the Four Seasons down the street. For the economy hotel chain to appeal to Four Seasons customers, it would have to invest in internal improvements, prime real estate, and an expensive service staff. Doing so would force it to adopt the same cost structure as the Four Seasons, so it would have to charge its customers similarly.

By contrast, in a disruptive innovation, an upstart can maintain its advantage while it improves its performance. What made the PC a disruptive innovation rather than just a low-end minicomputer, for instance, was the radical cost advantage its manufacturers achieved when they assembled their machines using standardized components. As component makers steadily improved the price and performance of their offerings, PC makers could preserve (or increase) their cost advantage even as they increased the power, capacity, and utility of their machines. This option was unavailable to minicomputer makers, because their improvements were derived from ever more effective designs of costly custom systems.

Not all the advantages of a disrupter’s extendable core are so overpowering; often they are offset by disadvantages. Take the current disruption of higher education. Online universities can enroll, educate, and grant degrees to far more students at much lower cost than traditional institutions of higher learning can, because e-learning technologies enable every faculty member to reach far more people than any single professor could address in even the largest university lecture hall. The initial quality of e-learning institutions left something to be desired, but—as the theory of disruption predicts—they have been improving the effectiveness of their programs while maintaining their cost and convenience advantages, thus attracting more students away from traditional alternatives.

But consider two groups of students these online universities have difficulty serving. One group is those who are looking to burnish their résumés by demonstrating that they are good enough to get into an exclusive college. The online universities’ extendable core is not much use here because their advantage lies in serving ever greater numbers of students with the same material—hardly a demonstration of exclusivity.

The other group is students who value the social aspects of college: the growth opportunities in living away from home, the close community of peers, the storied sports teams. E-learning institutions can (and do) opt to offer both online and on-campus courses in order to attract the widest variety of students, but they can’t bring their full disruptive advantage to bear here, because each added service forces them further toward the cost structure of traditional universities. Novel partnerships or technological innovations might eventually enable them to address this problem, but their extendable core in its current form falls short of satisfying these students.

Identifying a disrupter’s extendable core tells you what kinds of customers the disrupter might attract and—just as important—what kinds it won’t. How many customers of each kind do you have? To answer that question, you need to consider what people are really doing when they buy your products and services.

Where Advantage Matters

Why do people long for certain products and services in some situations but not in others? Experts in disruption have a ready answer: to complete some job that crops up in their lives. A college student doesn’t go shopping for floor cleaner, sponges, and a bucket for their own sake. Something—say, the impending arrival of his parents—makes it necessary for him to clean his room, so he seeks some product or service with which to do it. The floor cleaner, sponges, and bucket have no intrinsic value for him. It’s their ability to keep him on good terms with his family that he cares about.

Successful entrepreneurs naturally look at opportunities in terms of the jobs they can do for customers. An innovator observing the plight of our student might realize that he doesn’t care about keeping his room clean all the time, so he’s not interested in stocking up on cleaning supplies. Because he doesn’t clean often and may not be good at it, he’s probably looking for something simple and foolproof. And he has probably waited to clean until just before his parents arrive (so that his room will stay neat), which means he needs to do the job quickly. An enterprising fellow student might see that as an opportunity to start a 30-minute emergency cleaning service on campus. A consumer goods company might consider bundling small amounts of appropriate cleaning supplies and making them conveniently available at university bookstores, nearby pharmacies, or even coffee shops.

Identifying what jobs people need done and how they could be done more easily, conveniently, or affordably is what enables a disrupter to imagine how to improve its product to appeal to more and more of your customers. If you can determine how effective or ineffective the disrupter is likely to be at doing the jobs you currently do, you can identify the most vulnerable segments of your core business—and your most sustainable advantages. When a disruptive business offers a significant advantage and no disadvantages in doing the same job you do, disruption will be swift and complete (think online music versus CDs). But when the advantages of a disrupter’s extendable core are ill suited to doing that job and its disadvantages are considerable, disruption will be slower and incomplete. Thus, at the simplest level, cargo ships are still in use because they’re still much better than planes at transporting heavy goods. Box-office receipts still represent a large portion of studio revenues in part because sizable groups of people (teenage boys, dating couples) go to the movies to get out of the house. Ivy League universities are still better positioned than online institutions to confer elite status on aspiring high school seniors.

When Advantage Persists

Could something happen to make cargo ships obsolete or to decrease the value of an elite education? To find out, we need to consider how easily a disrupter could overcome its disadvantages in the future—to ask, “What would have to change for my current advantages to evaporate?" To approach this question, we propose a systematic assessment of five kinds of barriers to disruption, arranged here from easiest to overcome to hardest.

The momentum barrier (customers are used to the status quo)

The tech-implementation barrier (which could be overcome using existing technology)

The ecosystem barrier (which would require a change in the business environment to overcome)

The new-technologies barrier (the technology needed to change the competitive landscape does not yet exist)

The business model barrier (the disrupter would have to adopt your cost structure)

The more difficult the barrier, or the more barriers a disrupter faces, the more likely it is that customers will remain with incumbents. Cargo ships, whose containers are designed to move seamlessly from quay to rail to truck to loading dock, benefit from an ecosystem barrier, which airlines might conceivably assault with an integrated system of their own. Far more formidable, of course, is the new-technologies barrier to developing cheap, renewable jet fuel, which would enable airlines to dramatically lower the cost of air shipping.

This approach may seem intuitive, but decades of training have taught executives to focus not on the value they provide for their customers but on proxies for it—high-level profit and revenue data. If an innovator is causing a company losses, it’s deemed threatening. If not, it’s often dismissed. And overestimating a threat can be as costly as ignoring it: Managers struggle to keep customers who are unlikely to be lost to disruption in the same way they would compete with traditional rivals—by dropping prices or offering comparable product features. This sort of response both fails to identify the intrinsic advantage of the disrupter and ignores advantages that the legacy business could viably defend.

To many, it may be clear why ships still carry cargo and why the disruption of the movie theater by DVDs is incomplete. However, that clarity is easier to achieve in retrospect than it was on the precipice of disruption. During the 1980s content producers were up in arms over the spread of home video distribution. Today those same studios are fighting frantically to limit the adoption of digital streaming—which, although it certainly represents an improvement over (and a direct threat to) DVDs, remains at a distinct disadvantage in doing many of the jobs that movie theaters still perform.

To demonstrate how our approach can be applied both in more-ambiguous cases and in a prescriptive fashion, let’s turn to a disruption that’s occurring right now.

The Disruption of Retail Grocery Stores

Over the past 15 years online retailing has devastated traditional brick-and-mortar retailers. The disruption began with the swift destruction of companies such as Tower Records and Hollywood Video and has taken its toll on high-margin retailers like Neiman Marcus and Saks Fifth Avenue. Retail continues to be a hotbed of entrepreneurship and innovation.

One of the last bastions against this disruptive wave is the grocery industry. Only about 1% of all groceries in the United States are bought from online retailers like Peapod, NetGrocer, and FreshDirect. However, we can expect that with an incentive to innovate their way upmarket, e-grocers will become increasingly significant. The theory of disruption tells us that these entrants will speed their delivery times, increase their product selection, and add features we can hardly imagine today in pursuit of new customers and higher profit margins. Even now, Amazon is making more and more grocery staples available online and is experimenting with discounted prices for automatic replenishment services. And Walmart has constructed convenient urban pickup centers for items bought online.

Questions for the executives of Kroger, Safeway, Whole Foods, and the like are “How complete will the grocery industry’s disruption become?" and “What role will traditional brick-and-mortar stores play in the grocery market of the future?"

Online Grocers’ Extendable Core

We all intuitively grasp the advantages of online retailing. But for businesses attempting to predict the extent and impact of disruption, intuition isn’t always enough. When Amazon first opened its virtual doors, most people saw only its most salient advantage—the deep price discounts it could offer by passing along the cost savings it gained from dispensing with physical retail outlets. A more careful analysis of its business model revealed that cash flow was an even greater advantage: Consumers gave Amazon their money before Amazon had to pay its suppliers for inventory. (This was so lucrative that it helped to fund much of Amazon’s early development.) Conceivably, anything sold online, whether books or cornflakes, has a similar advantage. Online grocers can reduce their inventory by centralizing warehouses and can pay less for products than traditional grocery chains do by purchasing them on an even greater scale. They don’t have to pay costly sales staff. And sometimes, through careful warehouse placement, they can avoid paying state sales taxes.

On the downside, though, online grocers have to ship their products to individual homes—far more destinations than any brick-and-mortar grocer need worry about. They must manage complex logistics chains to coordinate shipments of the various items that make up a grocery order, whereas supermarket shoppers merely toss everything into a cart and wheel it to the front of the store. The lack of sales staff limits customer service for online grocers. And for consumers, the convenience of shopping from home comes at the expense of direct physical contact with the goods.

Which of these advantages and disadvantages do the managers at Kroger and Whole Foods need to focus on? To answer that question, they must discover just how shoppers are using their stores.

The Jobs Brick-and-Mortar Grocers Do

We find that the best way to identify the jobs a company does for its customers is through a combination of extensive surveys, interviews, focus groups, and in-person observations. Spend a day near a Kroger exit, and you’ll see a few distinct patterns. In the morning and early afternoon, many customers spend a substantial amount of time in all the store’s aisles loading up large grocery carts. Occasionally a customer zips in to buy one or two items and checks out in the express lane. Late in the afternoon, a handful of customers are still filling their carts with staples, but far more are picking up fresh vegetables, proteins, and the occasional baked good.

At the end of the day, if you had taken notes and interviewed a few customers about what they came to the store to accomplish (and what alternatives they use for the same purpose), you’d probably be ready to identify at least some of the jobs customers were hiring Kroger to complete. The people filling their carts were stocking up on products they knew in advance they would need—the weekly grocery pickup. The ones zipping in and out were after some emergency item they’d forgotten or something essential sold only by that market. The shoppers arriving during the afternoon rush were gathering ingredients for that night’s dinner. These three jobs are by no means comprehensive, but they are big enough drivers of the customer population to shed light on the pace of grocery’s disruption and on what the industry will look like in its wake.

You might assume that this sort of intention analysis is common, but it happens far less often than it should. Advances in data collection and analysis have made it possible to get ever more detailed information about who’s buying, what they’re buying, how often they’re buying, and whom they’re with when they’re buying. Typically, consulting firms and internal strategy teams take reams of such data, crunch the numbers, and organize people into segments such as “frequent shoppers," “young parents," and “discount hunters." These labels appear to be aimed at uncovering intentions, but they essentially remain descriptions of types of people, and thus tell us little about behavior in certain circumstances.

For instance, at the onset of a disruption, we might know that Kroger’s most frequent shoppers were young mothers, but we wouldn’t know what they were doing when they came into the store. The same woman might on one occasion walk methodically up and down the aisles, stocking up on the week’s nonperishables, and on another might be dashing in to grab a forgotten item or two. She might also be returning practically every evening at 5:30 to buy the ingredients for that night’s dinner. Or not. Without an understanding of what she’s trying to accomplish each time she visits, it’s impossible to identify what innovations might matter to her when she walks through the door.

Once you understand what jobs customers most commonly hire you to do, it becomes much easier to begin evaluating how important the advantages and disadvantages of a disrupter’s extendable core are to your business. Take the job of providing emergency goods. Imagine that it’s 8:45 p.m. and you’ve just realized that you’re out of toothpaste. You immediately head to a store to ensure that you’ll avoid the costly impact of gingivitis. You’re not thinking about the advantages of shopping from home, the selection offered by nearly infinite shelf space, or the low price afforded by scale. You’re focused on instant delivery. In deciding which store to visit, you find yourself comparing the traditional competitive advantages of physical retailers such as 7-Eleven, CVS, and the supermarket. The decision comes down to which of those stores is closest to you and whether you think it will have your favorite toothpaste (or at least an acceptable alternative) in stock. In this situation an online retailer’s advantages are simply not relevant to you.

Consider the job of buying dinner, and you’ll reach a similar conclusion about the relative advantages of brick-and-mortar markets over online retailing. Interviews with shoppers who are picking up dinner ingredients reveal that they typically don’t decide what they’re going to buy until they’re at the store. Many use the store’s selection to narrow down the possibilities—seeing what looks appealing helps them with the task of planning dinner day after day. They are likely to place a high value on obtaining the freshest ingredients. Because each tomato, steak, or bunch of grapes is different, they want to pick up and examine the perishable ingredients they’re considering. Although FreshDirect and Peapod may guarantee freshness, these shoppers feel comforted by seeing the product in person. Only a compelling offer, such as Gilt Taste’s gourmet products at steeply reduced prices, can substitute for their own judgment. Absent such a strong point of differentiation, customers turn to supermarkets, farmers’ markets, and corner stores to get the job done. The convenience of online retail is simply not enough.

Just as we can envision the difficulties a disrupter would have in completing the emergency-item and dinner-shopping jobs, we can see how vulnerable the staples-shopping job is. Shoppers stocking up on branded nonperishables such as canned tuna, coffee, pancake mix, and spaghetti sauce know what they want and generally don’t require it immediately. A sizable number of them already wait until they need a sufficient quantity to justify a trip to BJ’s or Costco. Shopping on Amazon and waiting a few days for the items to be delivered is not so different. This is the job, our analysis suggests, that is most susceptible to disruption by online grocers. The early successes of Diapers.com and Soap.com in selling branded nonperishables traditionally provided by physical grocery stores is a harbinger of the coming shift.

The Barriers to Disruption

We can see disruption on the horizon, but how close is it? Returning to the five barriers—momentum, tech implementation, ecosystem, new technologies, business model—we can see that for online grocers to overcome their disadvantage in doing the job of providing emergency goods, they would have to engage in a costly infrastructure extension, either to build their own stores and adopt their traditional competitors’ cost structures, or to send delivery trucks out at nowhere near optimum capacity. So for this job, disrupters are hitting the formidable business model barrier. Because either change would destroy their advantage, we can label this disadvantage significant and difficult to overcome.

A disrupter that is trying to do the job of stocking up on staples clearly encounters no business model barrier, no new-technology barrier, no genuine tech-implementation barrier, and a weakening momentum barrier. Still, one could argue that daily trips to the grocery store for dinner or emergency items might make the thought of shopping online for nonperishables seem duplicative. But this is true only as long as it makes sense to shop at traditional grocery stores. What if farmers’ markets continue to proliferate, or if a traditional competitor—say, Trader Joe’s—chooses to invest in smaller-format urban grocery stores that feature fewer staples and more fresh goods? Then it may well become sensible for consumers to shop for nonperishables separately. Because we can envision that such an ecosystem shift will result naturally from entrepreneurs’ pursuit of profit, we predict that disruption will arrive sooner rather than later.

The Path Forward

Online grocers constitute a viable and potent threat when it comes to the job of delivering products we know in advance that we need. Customers who hire traditional grocers to do that job already value the broad selection and lower prices that online grocers are poised to provide. Over time, as they get used to shopping online, they may also come to value free delivery and the savings on gasoline they achieve by eliminating errands. As more customers adopt the online format, it will become ever more difficult for brick-and-mortar grocers to compete here. Legacy grocers could establish discount programs, secure exclusive distribution, put bigger stores in more-convenient locations, institute or expand loyalty programs that offer savings on gas to retain shoppers who are looking to stock up. But ultimately those efforts will be futile. As online grocers grow in scale, they will be able to offer better discount programs, match loyalty programs, work to secure the same exclusive distribution. Wise brick-and-mortar grocers won’t fight this disruption head-on. They will instead focus on developing innovations aimed at completing their still-defensible jobs—serving the emergency shopper and the harried soul who is trying to put dinner on the table.

To better serve those customers, traditional grocery retailers should focus on outcompeting convenience stores with lower prices and better quality (particularly of perishables) and outcompeting farmers’ markets—perhaps with greater selection or by enticing farmers to sell produce inside their stores. They should be thinking hard about their physical advantages—considering how store layouts might help or hinder the shopper who is trying to gather ingredients for dinner. They might mimic England’s Marks & Spencer by offering high-end semiprepared meals to recapture some of the margin lost from shrinking sales of branded nonperishables. Some might even experiment with locating shelf space inside other conveniently located retail outlets: A branded Trader Joe’s aisle inside CVS would allow both retailers to better serve customers. Knowing where you’re likely to succeed and where you’re not is the key to making critical resource allocation decisions—not in the service of ephemeral short-term margins but in the realistic pursuit of longer-term competitive advantage.

![]()

The missiles of disruption are aimed at your local Kroger, Whole Foods, and Safeway. Their leaders should expect increasing competition from online upstarts for the highly profitable branded items that currently fill so many supermarket aisles. They would do well to plan for a world in which those revenues are in some large part lost to them forever.

Accepting the existence of a new competitive paradigm is never easy. It often forces us to acknowledge an inevitable loss of business. It may require us to develop disruptions that cannibalize our existing businesses. Failing to come to terms with these realities does us no service.

But neither does prematurely convincing ourselves of the singular superiority of a competitor’s disruptive advantages. After all, Kroger, Whole Foods, and Safeway still perform important functions for millions of people that no online grocer will be able to perform anytime soon. Before leaders engage in reckless price competition or squander resources and effort in the futile defense of lost causes, they owe it to their shareholders, employees, and customers to take stock of the entire situation and respond comprehensively—to meet disrupters with disruption of their own, but also to guide their legacy businesses toward as healthy a future as possible.

Originally published in December 2012. Reprint R1212C