Is It Real? Can We Win? Is It Worth Doing?

Managing Risk and Reward in an Innovation Portfolio. by George S. Day

MINOR INNOVATIONS MAKE up 85% to 90% of companies’ development portfolios, on average, but they rarely generate the growth companies seek. At a time when companies should be taking bigger—but smart—innovation risks, their bias is in the other direction. From 1990 to 2004 the percentage of major innovations in development portfolios dropped from 20.4 to 11.5—even as the number of growth initiatives rose.1 The result is internal traffic jams of safe, incremental innovations that delay all projects, stress organizations, and fail to achieve revenue goals.

These small projects, which I call “little i” innovations, are necessary for continuous improvement, but they don’t give companies a competitive edge or contribute much to profitability. It’s the risky “Big I” projects—new to the company or new to the world—that push the firm into adjacent markets or novel technologies and can generate the profits needed to close the gap between revenue forecasts and growth goals. (According to one study, only 14% of new-product launches were substantial innovations, but they accounted for 61% of all profit from innovations among the companies examined.)2

The aversion to Big I projects stems from a belief that they are too risky and their rewards (if any) will accrue too far in the future. Certainly the probability of failure rises sharply when a company ventures beyond incremental initiatives within familiar markets. But avoiding risky projects altogether can strangle growth. The solution is to pursue a disciplined, systematic process that will distribute your innovations more evenly across the spectrum of risk.

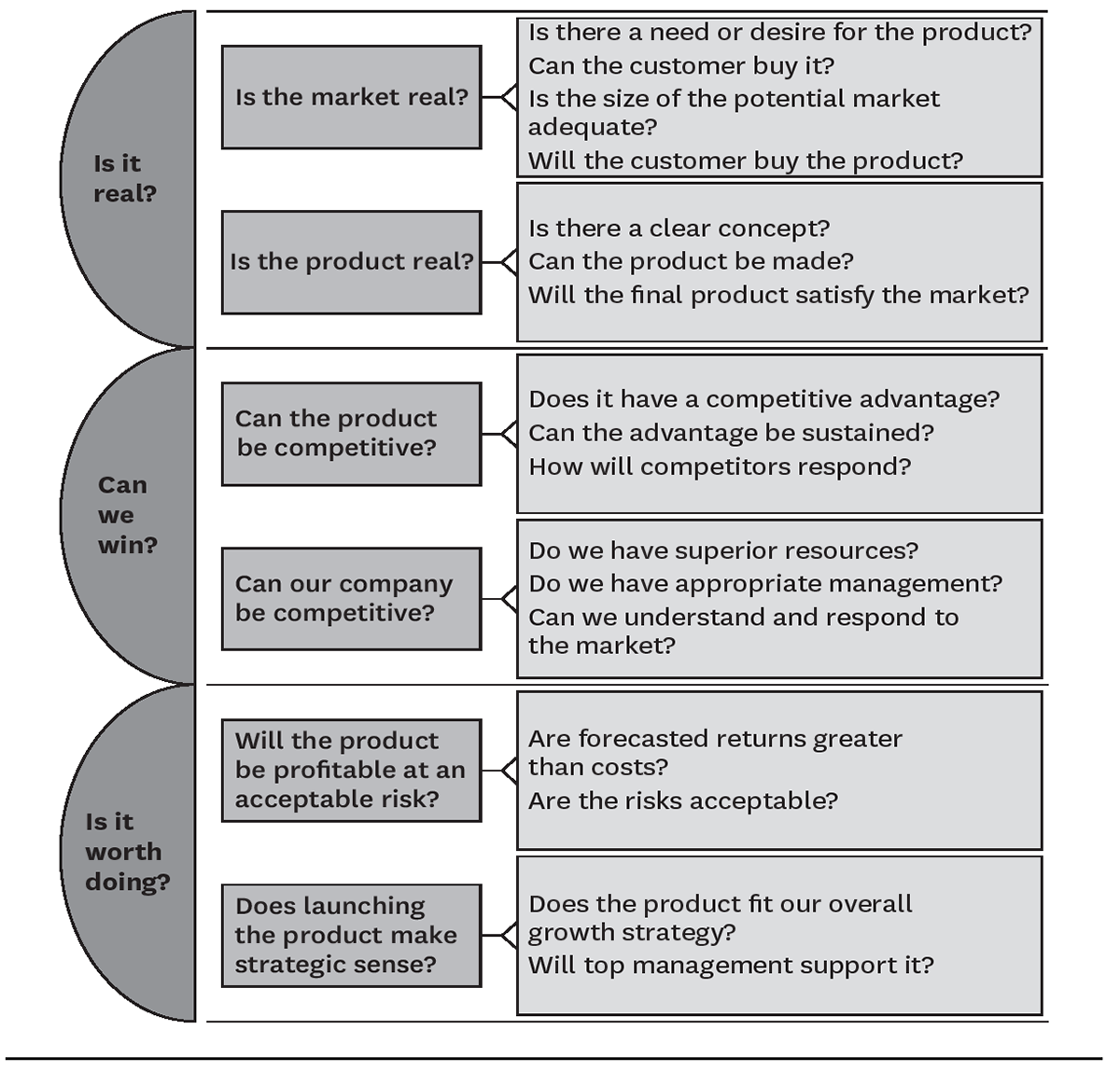

Two tools, used in tandem, can help companies do this. The first, the risk matrix, will graphically reveal risk exposure across an entire innovation portfolio. The second, the R-W-W (“real, win, worth it”) screen, originated by Dominick (“Don”) M. Schrello, of Long Beach, California, can be used to evaluate individual projects. Versions of the screen have been circulating since the 1980s, and since then a growing roster of companies, including General Electric, Honeywell, Novartis, Millipore, and 3M, have used them to assess business potential and risk exposure in their innovation portfolios; 3M has used R-W-W for more than 1,500 projects. I have expanded the screen and used it to evaluate dozens of projects at four global companies, and I have taught executives and Wharton students how to use it as well.

Although both tools, and the steps within them, are presented sequentially here, their actual use is not always linear. The information derived from each one can often be reapplied in later stages of development, and the two tools may inform each other. Usually, development teams quickly discover when and how to improvise on the tools’ structured approach in order to maximize learning and value.

The Risk Matrix

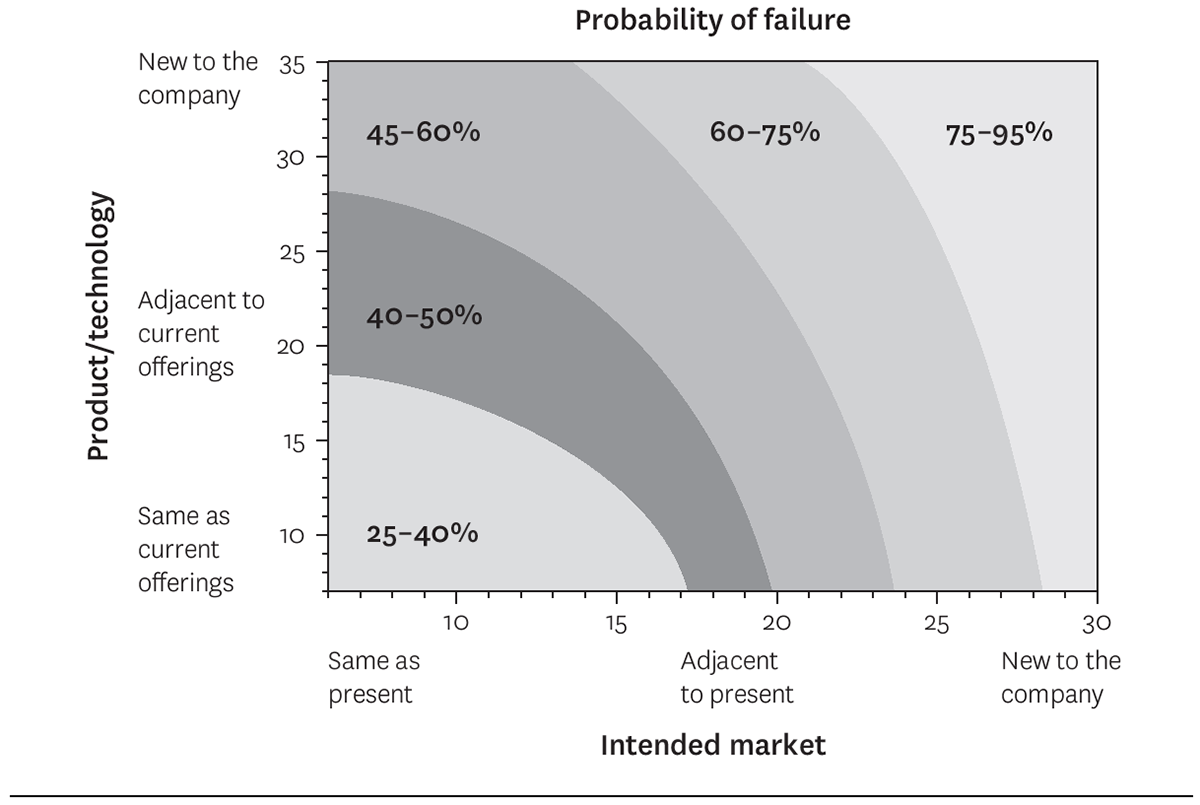

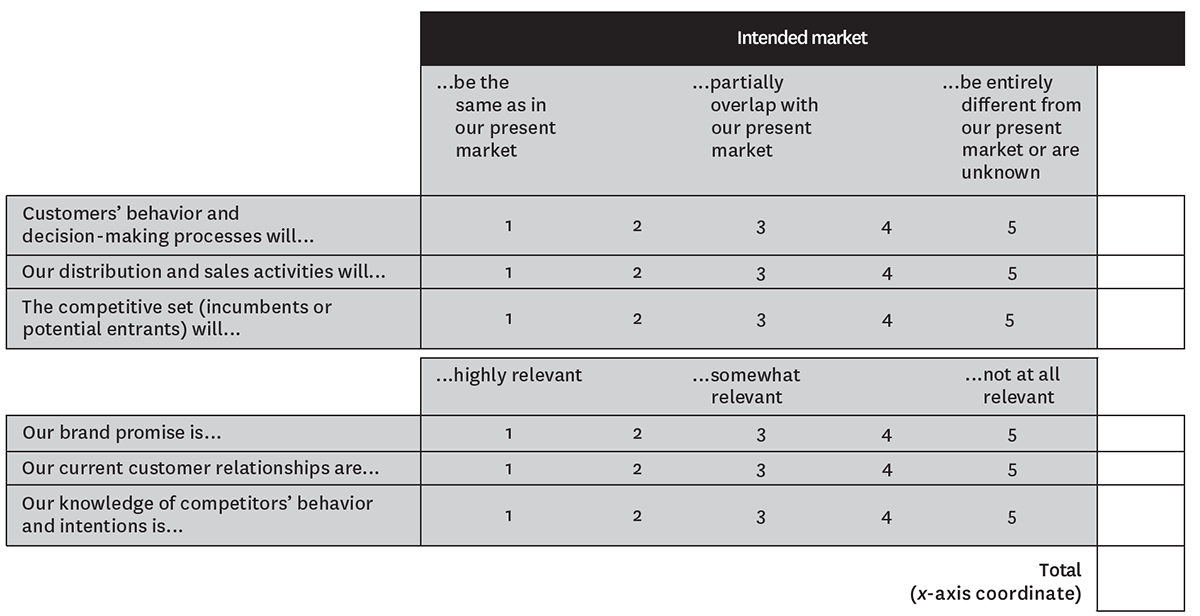

To balance its innovation portfolio, a company needs a clear picture of how its projects fall on the spectrum of risk. The risk matrix employs a unique scoring system and calibration of risk to help estimate the probability of success or failure for each project based on how big a stretch it is for the firm: The less familiar the intended market (x axis) and the product or technology (y axis), the higher the risk. (See the exhibit “Assessing risk across an innovation portfolio.”)

A project’s position on the matrix is determined by its score on a range of factors, such as how closely the behavior of targeted customers will match that of the company’s current customers, how relevant the company’s brand is to the intended market, and how applicable its technology capabilities are to the new product.

A portfolio review team—typically consisting of senior managers with strategic oversight and authority over development budgets and allocations—conducts the evaluation, with the support of each project’s development team. Team members rate each project independently and then explain their rationale. They discuss reasons for any differences of opinion and seek consensus. The resulting scores serve as a project’s coordinates on the risk matrix.

The determination of each score requires deep insights. When McDonald’s attempted to offer pizza, for example, it assumed that the new offering was closely adjacent to its existing ones, and thus targeted its usual customers. Under that assumption, pizza would be a familiar product for the present market and would appear in the bottom left of the risk matrix. But the project failed, and a postmortem showed that the launch had been fraught with risk: Because no one could figure out how to make and serve a pizza in 30 seconds or less, orders caused long backups, violating the McDonald’s service-delivery model. The postmortem also revealed that the company’s brand didn’t give “permission” to offer pizza. Even though its core fast-food customers were demographically similar to pizza lovers, their expectations about the McDonald’s experience didn’t include pizza.

Once the risk matrix has been completed, it typically reveals two things: that a company has more projects than it can manage well, and that the distribution of Big I and little i innovations is lopsided. Most companies will find that the majority of their projects cluster in the bottom left quadrant of the matrix, and a minority skew toward the upper right.

This imbalance is unhealthy if unsurprising. Discounted cash flow analysis and other financial yardsticks for evaluating development projects are usually biased against the delayed payoffs and uncertainty inherent in Big I innovations. What’s more, little i projects tend to drain R&D budgets as companies struggle to keep up with customers’ and salespeople’s demands for a continuous flow of incrementally improved products. The risk matrix creates a visual starting point for an ongoing dialogue about the company’s mix of projects and their fit with strategy and risk tolerance. The next step is to look closely at each project’s prospects in the marketplace.

Screening with R-W-W

The R-W-W screen is a simple but powerful tool built on a series of questions about the innovation concept or product, its potential market, and the company’s capabilities and competition (see the exhibit “Screening for success”). It is not an algorithm for making go/no-go decisions but, rather, a disciplined process that can be employed at multiple stages of product development to expose faulty assumptions, gaps in knowledge, and potential sources of risk, and to ensure that every avenue for improvement has been explored. The R-W-W screen can be used to identify and help fix problems that are miring a project, to contain risk, and to expose problems that can’t be fixed and therefore should lead to termination.

Innovation is inherently messy, nonlinear, and iterative. For simplicity, this article focuses on using the R-W-W screen in the early stages to test the viability of product concepts. In reality, however, a given product would be screened repeatedly during development—at the concept stage, during prototyping, and early in the launch planning. Repeated assessment allows screeners to incorporate increasingly detailed product, market, and financial analyses into the evaluation, yielding ever more accurate answers to the screening questions.

R-W-W guides a development team to dig deeply for the answers to six fundamental questions: Is the market real? Is the product real? Can the product be competitive? Can our company be competitive? Will the product be profitable at an acceptable risk? Does launching the product make strategic sense?

The development team answers these queries by exploring an even deeper set of supporting questions. The team determines where the answer to each question falls on a continuum ranging from definitely yes to definitely no. A definite no to any of the first five fundamental questions typically leads to termination of the project, for obvious reasons. For example, if the consensus answer to Can the product be competitive? is a definite no, and the team can imagine no way to change it to a yes (or even a maybe), continuing with development is irrational. When a project has passed all other tests in the screen, however, and thus is a very good business bet, companies are sometimes more forgiving of a no to the sixth question, Does launching the product make strategic sense?

This article will delineate the screening process and demonstrate the depth of probing needed to arrive at valid answers. What follows is not, of course, a comprehensive guide to all the issues that might be raised by each question. Development teams can probe more or less deeply, as needed, at each decision point. (For more on team process, see the sidebar “The Screening Team.”)

Is It Real?

Figuring out whether a market exists and whether a product can be made to satisfy that market are the first steps in screening a product concept. Those steps will indicate the degree of opportunity for any firm considering the potential market, so the inquiring company can assess how competitive the environment might be right from the start.

One might think that asking if the envisioned product is even a possibility should come before investigating the potential market. But establishing that the market is real takes precedence for two reasons: First, the robustness of a market is almost always less certain than the technological ability to make something. This is one of the messages of the risk matrix, which shows that the probability of a product failure becomes greater when the market is unfamiliar to the company than when the product or technology is unfamiliar. A company’s ability to crystallize the market concept—the target segment and how the product can do a better job of meeting its needs—is far more important than how well the company fields a fundamentally new product or technology. In fact, research by Procter & Gamble suggests that 70% of product failures across most categories occur because companies misconstrue the market. New Coke is a classic market-concept failure; Netflix got the market concept right. In each case the outcome was determined by the company’s understanding of the market, not its facility with the enabling technologies.

Second, establishing the nature of the market can head off a costly “technology push.” This syndrome often afflicts companies that emphasize how to solve a problem rather than what problem should be solved or what customer desires need to be satisfied. Segway, with its Personal Transporter, and Motorola, with its Iridium satellite phone, both succumbed to technology push. Segway’s PT was an ingenious way to gyroscopically stabilize a two-wheeled platform, but it didn’t solve the mobility problems of any target market. The reasons for Iridium’s demise are much debated, but one possibility is that mobile satellite services proved less able than terrestrial wireless roaming services to cost-effectively meet the needs of most travelers.

Whether the market and the product are real should dominate the screening dialogue early in the development process, especially for Big I innovations. In the case of little i innovations, a close alternative will already be on the market, which has been proved to be real.

Is the market real?

A market opportunity is real only when four conditions are satisfied: The proposed product will clearly meet a need or solve a problem better than available alternatives; customers are able to buy it; the potential market is big enough to be worth pursuing; and customers are willing to buy the product.

Is there a need or desire for the product? Unmet or poorly satisfied needs must be surfaced through market research using observational, ethnographic, and other tools to explore customers’ behaviors, desires, motivations, and frustrations. Segway’s poor showing is partly a market-research failure; the company didn’t establish at the outset that consumers actually had a need for a self-balancing two-wheeled transporter.

Once a need has been identified, the next question is, Can the customer buy it? Even if the proposed product would satisfy a need and offer superior value, the market isn’t real when there are objective barriers to purchasing it. Will budgetary constraints prevent customers from buying? (Teachers and school boards, for example, are always eager to invest in educational technologies but often can’t find the funding.) Are there regulatory requirements that the new product may not meet? Are customers bound by contracts that would prevent them from switching to a new product? Could manufacturing or distribution problems prevent them from obtaining it?

The team next needs to ask, Is the size of the potential market adequate? It’s dangerous to venture into a “trombone oil” market, where the product may provide distinctive value that satisfies a need, but the need is minuscule. A market opportunity isn’t real unless there are enough potential buyers to warrant developing the product.

Finally, having established customers’ need and ability to buy, the team must ask, Will the customer buy the product? Are there subjective barriers to purchasing it? If alternatives to the product exist, customers will evaluate them and consider, among other things, whether the new product delivers greater value in terms of features, capabilities, or cost. Improved value doesn’t necessarily mean more capabilities, of course. Many Big I innovations, such as the Nintendo Wii, home defibrillators, and Salesforce.com’s CRM software as a service, have prevailed by outperforming the incumbents on a few measures while being merely adequate on others. By the same token, some Big I innovations have stumbled because although they had novel capabilities, customers didn’t find them superior to the incumbents.

Even when customers have a clear need or desire, old habits, the perception that a switch is too much trouble, or a belief that the purchase is risky can inhibit them. One company encountered just such a problem during the launch of a promising new epoxy for repairing machine parts during routine maintenance. Although the product could prevent costly shutdowns and thus offered unique value, the plant engineers and production managers at whom it was targeted vetoed its use. The engineers wanted more proof of the product’s efficacy, while the production managers feared that it would damage equipment. Both groups were risk avoiders. A postmortem of the troubled launch revealed that maintenance people, unlike plant engineers and production managers, like to try new solutions. What’s more, they could buy the product independently out of their own budgets, circumventing potential vetoes from higher up. The product was relaunched targeting maintenance and went on to become successful, but the delay was expensive and could have been avoided with better screening.

Customers may also be inhibited by a belief that the product will fail to deliver on its promise or that a better alternative might soon become available. Addressing this reluctance requires foresight into the possibilities of improvement among competitors. The prospects of third-generation (3G) mobile phones were dampened by enhancements in 2.5G phones, such as high-sensitivity antennae that made the incumbent technology perform much better.

Is the product real?

Once a company has established the reality of the market, it should look closely at the product concept and expand its examination of the intended market.

Is there a clear concept? Before development begins, the technology and performance requirements of the concept are usually poorly defined, and team members often have diverging ideas about the product’s precise characteristics. This is the time to expose those ideas and identify exactly what is to be developed. As the project progresses and the team becomes immersed in market realities, the requirements should be clarified. This entails not only nailing down technical specifications but also evaluating the concept’s legal, social, and environmental acceptability.

Can the product be made? If the concept is solid, the team must next explore whether a viable product is feasible. Could it be created with available technology and materials, or would it require a breakthrough of some sort? If the product can be made, can it be produced and delivered cost-effectively, or would it be so expensive that potential customers would shun it? Feasibility also requires either that a value chain for the proposed product exists or that it can be easily and affordably developed, and that de facto technology standards (such as those ensuring compatibility among products) can be met.

Some years ago the R-W-W screen was used to evaluate a radical proposal to build nuclear power–generating stations on enormous floating platforms moored offshore. Power companies were drawn to the idea, because it solved both cooling and not-in-my-backyard problems. But the team addressing the Is the product real? stage of the process found that the inevitable flexing of the giant platforms would lead to metal fatigue and joint wear in pumps and turbines. Since this problem was deemed insurmountable, the team concluded that absent some technological breakthrough, the no answer to the feasibility question could never become even a maybe, and development was halted.

Will the final product satisfy the market? During development, trade-offs are made in performance attributes; unforeseen technical, manufacturing, or systems problems arise; and features are modified. At each such turn in the road, a product designed to meet customer expectations may lose some of its potential appeal. Failure to monitor these shifts can result in the launch of an offering that looked great on the drawing board but falls flat in the marketplace.

Consider the ongoing disappointment of e-books. Even though the newest entrant, the Sony Reader, boasts a huge memory and breakthrough display technology, using it doesn’t begin to compare with the experience of reading conventional books. The promised black-on-white effect is closer to dark gray on light gray. Meanwhile, the Reader’s unique features, such as the ability to store many volumes and to search text, are for many consumers insufficiently attractive to offset the near $300 price tag. Perhaps most important, consumers are well satisfied with ordinary books. By July of 2007 the entire e-book category had reached only $30 million in sales for the year.

Can We Win?

After determining that the market and the product are both real, the project team must assess the company’s ability to gain and hold an adequate share of the market. Simply finding a real opportunity doesn’t guarantee success: The more real the opportunity, the more likely it is that hungry competitors are eyeing it. And if the market is already established, incumbents will defend their positions by copying or leapfrogging any innovations.

Two of the top three reasons for new-product failures, as revealed by audits, would have been exposed by the Can we win? analysis: Either the new product didn’t achieve its market-share goals, or prices dropped much faster than expected. (The third reason is that the market was smaller, or grew more slowly, than expected.)

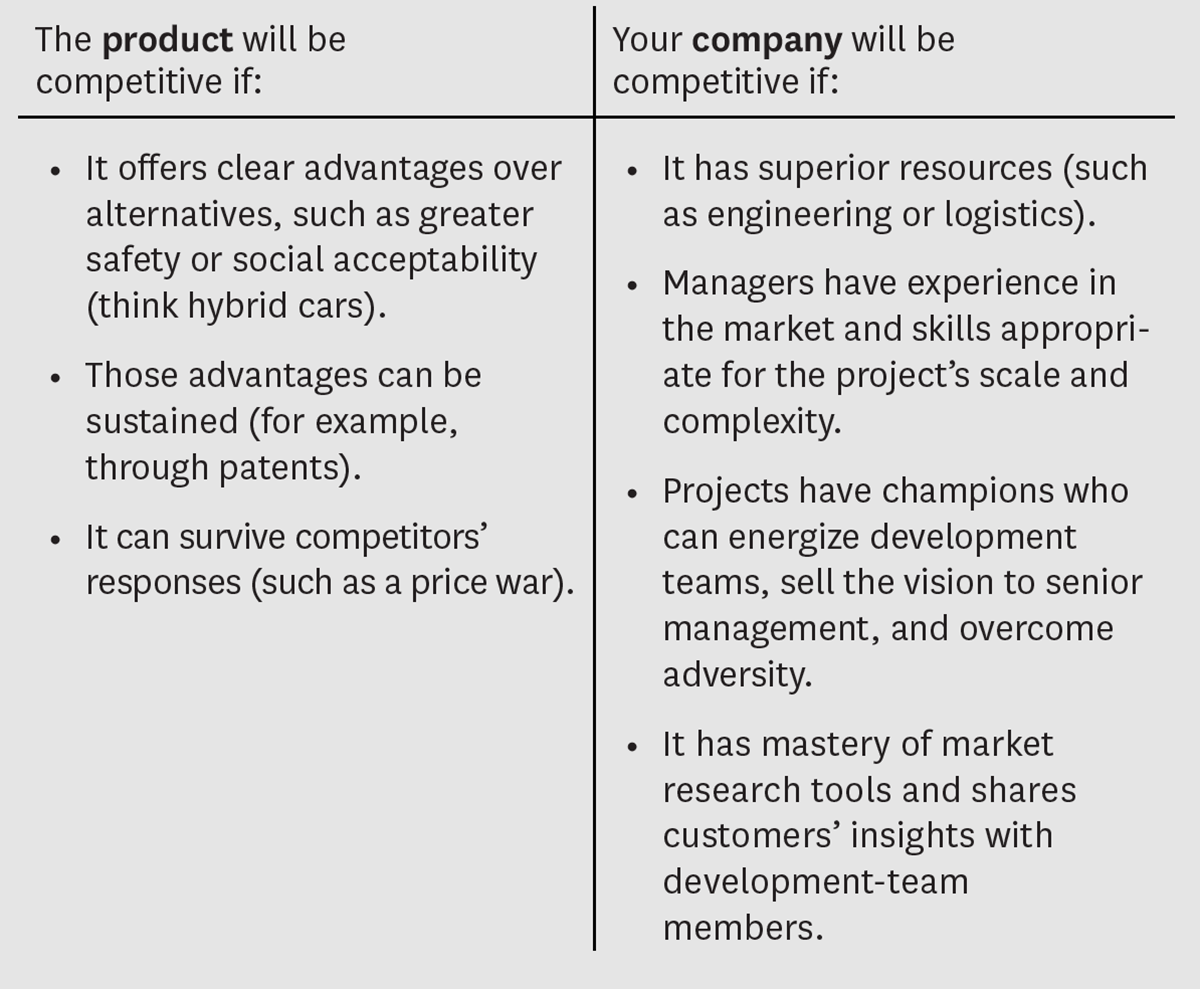

The questions at this stage of the R-W-W screening carefully distinguish between the offering’s ability to succeed in the marketplace and the company’s capacity—through resources and management talent—to help it do so.

Can the product be competitive?

Customers will choose one product over alternatives if it’s perceived as delivering superior value with some combination of benefits such as better features, lower life-cycle cost, and reduced risk. The team must assess all sources of perceived value for a given product and consider the question Does it have a competitive advantage? (Here the customer research that informed the team’s evaluation of whether the market and the product were real should be drawn on and extended as needed.) Can someone else’s offering provide customers with the same results or benefits? One company’s promising laminate technology, for instance, had intrigued technical experts, but the launch failed because the customers’ manufacturing people had found other, cheaper ways to achieve the same improvement. The team should also consider whether the product offers additional tangible advantages—such as lifetime cost savings, greater safety, higher quality, and lower maintenance or support needs—or intangible benefits, such as greater social acceptability (think of hybrid cars and synthetic-fur coats) and the promise of reduced risk that is implicit in a trusted brand name.

Can the advantage be sustained? Competitive advantage is only as good as the company’s ability to keep imitators at bay. The first line of defense is patents. The project team should evaluate the relevance of its existing patents to the product in development and decide what additional patents may be needed to protect related intellectual property. It should ask whether a competitor could reverse engineer the product or otherwise circumvent patents that are essential to the product’s success. If maintaining advantage lies in tacit organizational knowledge, can that knowledge be protected? For example, how can the company ensure that the people who have it will stay? What other barriers to imitation are possible? Can the company lock up scarce resources or enter into exclusive supply contracts?

Consider the case of 3M’s computer privacy screen. Although the company’s microlouver technology promised unique privacy benefits, its high price threatened to limit sales to a small market niche, making the project’s status uncertain. An R-W-W screening, however, revealed that the technology was aggressively patented, so no competitor could imitate its performance. It also clarified an opportunity in adjacent markets for antiglare filters for computers. Armed with these insights, 3M used the technology to launch a full line of privacy and antiglare screens while leveraging its brand equity and sales presence in the office-products market. Five years later the product line formed the basis of one of 3M’s fastest-growing businesses.

How will competitors respond? Assuming that patent protection is (or will be) in place, the project team needs to investigate competitive threats that patents can’t deflect. A good place to start is a “red team” exercise: If we were going to attack our own product, what vulnerabilities would we find? How can we reduce them? A common error companies make is to assume that competitors will stand still while the new entrant fine-tunes its product prior to launch. Thus the team must consider what competing products will look like when the offering is introduced, how competitors may react after the launch, and how the company could respond. Finally, the team should examine the possible effects of this competitive interplay on prices. Would the product survive a sustained price war?

Can our company be competitive?

After establishing that the offering can win, the team must determine whether or not the company’s resources, management, and market insight are better than those of the competition. If not, it may be impossible to sustain advantage, no matter how good the product.

Do we have superior resources? The odds of success increase markedly when a company has or can get resources that both enhance customers’ perception of the new product’s value and surpass those of competitors. Superior engineering, service delivery, logistics, or brand equity can give a new product an edge by better meeting customers’ expectations. The European no-frills airline easyJet, for example, has successfully expanded into cruises and car rentals by leveraging its ability to blend convenience, low cost, and market-appropriate branding to appeal to small-business people and other price-sensitive travelers.

If the company doesn’t have superior resources, addressing the deficiency is often straightforward. When the U.S. market leader for high-efficiency lighting products wanted to expand into the local-government market, for example, it recognized two barriers: The company was unknown to the buyers, and it had no experience with the competitive bidding process they used. It overcame these problems by hiring people who were skilled at analyzing competitors, anticipating their likely bids, and writing proposals. Some of these people came from the competition, which put the company’s rivals at a disadvantage.

Sometimes, though, deficiencies are more difficult to overcome, as is the case with brand equity. As part of its inquiry into resources, the project team must ask whether the company’s brand provides—or denies—permission to enter the market. The 3M name gave a big boost to the privacy screen because it is strongly associated with high-quality, innovative office supplies—whereas the McDonald’s name couldn’t stretch to include pizza. Had the company’s management asked whether its brand equity was both relevant and superior to that of the competition—such as Papa Gino’s—the answer would have been equivocal at best.

Do we have appropriate management? Here the team must examine whether the organization has direct or related experience with the market, whether its development-process skills are appropriate for the scale and complexity of the project, and whether the project both fits company culture and has a suitable champion. Success requires a passionate cheerleader who will energize the team, sell the vision to senior management, and overcome skepticism or adversity along the way. But because enthusiasm can blind champions to potentially crippling faults and lead to a biased search for evidence that confirms a project’s viability, their advocacy must be constructively challenged throughout the screening process.

Can we understand and respond to the market? Successful product development requires a mastery of market-research tools, an openness to customer insights, and the ability to share them with development-team members. Repeatedly seeking the feedback of potential customers to refine concepts, prototypes, and pricing ensures that products won’t have to be recycled through the development process to fix deficiencies.

Most companies wait until after development to figure out how to price the new product—and then sometimes discover that customers won’t pay. Procter & Gamble avoids this problem by including pricing research early in the development process. It also asks customers to actually buy products in development. Their answers to whether they would buy are not always reliable predictors of future purchasing behavior.

Is It Worth Doing?

Just because a project can pass the tests up to this point doesn’t mean it is worth pursuing. The final stage of the screening provides a more rigorous analysis of financial and strategic value.

Will the product be profitable at an acceptable risk?

Few products launch unless top management is persuaded that the answer to Are forecasted returns greater than costs? is definitely yes. This requires projecting the timing and amount of capital outlays, marketing expenses, costs, and margins; applying time to breakeven, cash flow, net present value, and other standard financial-performance measures; and estimating the profitability and cash flow from both aggressive and cautious launch plans. Financial projections should also include the cost of product extensions and enhancements needed to keep ahead of the competition.

Forecasts of financial returns from new products are notoriously unreliable. Project managers know they are competing with other worthy projects for scarce resources and don’t want theirs to be at a disadvantage. So it is not surprising that project teams’ financial reports usually meet upper management’s financial-performance requirements. Given the susceptibility of financial forecasts to manipulation, overconfidence, and bias, executives should depend on rigorous answers to the prior questions in the screen for their conclusions about profitability.

Are the risks acceptable? A forecast’s riskiness can be initially assessed with a standard sensitivity test: How will small changes in price, market share, and launch timing affect cash flows and breakeven points? A big change in financial results stemming from a small one in input assumptions indicates a high degree of risk. The financial analysis should consider opportunity costs: Committing resources to one project may hamper the development of others.

To understand risk at a deeper level, consider all the potential causes of product failure that have been unearthed by the R-W-W screen and devise ways to mitigate them—such as partnering with a company that has market or technology expertise your firm lacks.

Does launching the product make strategic sense?

Even when a market and a concept are real, the product and the company could win, and the project would be profitable, it may not make strategic sense to launch. To evaluate the strategic rationale for development, the project team should ask two more questions.

Does the product fit our overall growth strategy? In other words, will it enhance the company’s capabilities by, for example, driving the expansion of manufacturing, logistics, or other functions? Will it have a positive or a negative impact on brand equity? Will it cannibalize or improve sales of the company’s existing products? (If the former, is it better to cannibalize one’s own products than to lose sales to competitors?) Will it enhance or harm relationships with stakeholders—dealers, distributors, regulators, and so forth? Does the project create opportunities for follow-on business or new markets that would not be possible otherwise? (Such an opportunity helped 3M decide to launch its privacy screen: The product had only a modest market on its own, but the launch opened up a much bigger market for antiglare filters.) These questions can serve as a starting point for what must be a thorough evaluation of the product’s strategic fit. A discouraging answer to just one of them shouldn’t kill a project outright, but if the overall results suggest that a project makes little strategic sense, the launch is probably ill-advised.

Will top management support it? It’s certainly encouraging for a development team when management commits to the initial concept. But the ultimate success of a project is better assured if management signs on because the project’s assumptions can withstand the rigorous challenges of the R-W-W screen.

Notes

1. Robert G. Cooper, “Your NPD Portfolio May Be Harmful to Your Business Health,” PDMA Visions, April 2005.

2. W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne, “Strategy, Value Innovation, and the Knowledge Economy,” Sloan Management Review, Spring 1999.

Originally published in December 2007. Reprint R0712S