CHAPTER 13

Assess Performance, but Rethink Ratings

There is no one right way to conduct a performance appraisal, but you and your direct report will both benefit from your preparation. You must evaluate your direct report’s performance in relation to the goals you defined together. You can use the same methods described in section 2 to identify gaps between goals and performance.

You’ll also want to assess behaviors that may not be explicitly linked to any specific goal. Teamwork, communication skills, leadership, initiative, focus, productivity, and reliability are all competencies that affect how an employee gets work done. You may also want to consider whether or not someone has demonstrated citizenship behaviors, like helping their colleagues or making new hires feel welcome, which boost cooperation and improve the work environment.

Gather Information About Performance

Appraisals are too easily skewed by a manager’s limited perspective and selective memory. One big mistake or contribution over the course of the review period may stick in a manager’s mind and outweigh everything else their direct report has done during that time. And because an employee’s most recent performance is fresh in their manager’s mind, that behavior can weigh more heavily in the evaluation than it should. But you can help avoid these problems by drawing on different sources of information to get a fuller picture.

There are a number of resources to take under consideration when evaluating performance. If you’ve been keeping records on your ongoing feedback, coaching, and development conversations, you’ll have plenty of material to work with. You can also gather 360-degree feedback from others to complement your own observations. But to begin, you want to solicit your employee’s point of view.

Request an employee’s self-assessment

About two weeks before the review session, ask your direct report to complete a self-evaluation. This document allows you to take the employee’s input into account when you’re preparing for the conversation, rather than potentially being surprised by it just before or during the formal review. Such self-appraisal also has the benefit of setting a tone of partnership that may help the person be more open to subsequent feedback.

Some organizations provide specific self-evaluation forms or checklists. Questions on this form may include:

- What are your most important accomplishments since your last review?

- Have you achieved the goals set for this review period?

- Have you surpassed any of your goals? Which ones? What helped you exceed them?

- Are you currently struggling with any goals? Which ones? What is inhibiting your progress toward those goals (lack of training, inadequate resources, poor direction from management)?

- Has this review period been better or worse than previous ones in the position?

- What parts of your job do you find most and least interesting or enjoyable?

- What do you most like and dislike about working for this organization?

- What do you consider to be your most important tasks and aims for the upcoming year?

- What can I as your manager, or the organization as a whole, do to help you be more successful?

Answering these questions can enhance your employee’s ability to learn and reflect during your appraisal discussion. The very act of thinking them over will help the individual recognize the review not as a required drill but as a true effort toward helping them understand how they’re contributing to the organization and how they might build success.

Even if you aren’t required to use a formal self-appraisal form, it’s still worth soliciting some information from your direct report. Ask for an informal list of your direct report’s most important achievements and accomplishments—projects, tasks, relevant initiatives—over the review period to ensure you don’t overlook any of your employee’s successes. This can be as simple as an email with bullet points. You can also ask them for a list of people you could check with about their performance (the 360-degree feedback process). This input can give you a broader perspective on the employee’s work and any related problems, since as a manager you may be seeing just a small part of what the person does or struggles with every day. It will also help refresh your memory and put a positive slant on an event that so many participants dread.

Some argue that self-appraisals don’t work. For example, performance evaluation expert Dick Grote says that self-assessments give the employee the wrong impression of what an appraisal is, not to mention a false sense of collaboration, especially if someone’s performance is unacceptable. Having a direct report complete a self-appraisal cues them to expect that they’ll bring their evaluation, you’ll bring yours, and together you’ll come to an agreement on the final appraisal. But a performance evaluation is a record of your opinion of the quality of their work—not a negotiation.

In cases where there may be confusion—for example, an underperformer’s work is unacceptable and requires immediate change—you may choose not to solicit a self-assessment. But if you do use self-appraisals in the review process, make it clear to your direct report that their contribution is just one piece of the data that you’ll review when looking at the whole picture and that its purpose is for you to gain insight into their point of view.

Review your records

In addition to the employee’s self-assessment, read over any notes you’ve kept on your direct report over the review period. If you’ve kept robust records, you won’t need to rack your brain trying to remember what happened over the course of the year; you’ll have the information right in front of you.

If you’re preparing for a review and don’t have detailed records, consider what sources you do have to jog your memory. Skim through your calendar appointments to remind yourself of specific accomplishments or problems—the sales pitch delivered flawlessly, the deadline missed, or the time your employee smoothly covered for a colleague during flu season. Look through email correspondence and meeting notes to find similar details that may have escaped you.

Solicit 360-degree feedback

You may also want to consider complementing your own observations with 360-degree feedback: feedback from colleagues and others who work closely with your direct report. For instance, an “internal customer”—someone for whom your employee provides, say, tech or design services—and a peer who works with the employee on a cross-functional team might have valuable input on dimensions of the person’s work that you don’t see directly. Gaining observations from the employee’s larger community can expand your limited perspective.

This type of broad feedback that synthesizes others’ perspectives can reduce the chance of a performance misdiagnosis. It also recognizes that many modern workplaces are multifaceted, with no one person in particular seeing all dimensions of the employee’s work. Thus, several people in a position to know are asked to rate the quality of the subject’s performance and their interactions with them. Some organizations present this feedback anonymously; others have colleagues participate in direct conversations about one another’s work.

As a method, 360-degree feedback is not without drawbacks. First, it is time-consuming. Think for a moment about the many people whom you might be asked to rate in your organization. Your boss, four or five of your peers, the person who handles your department’s expense reimbursements, and so forth. Now multiply that number by the one hour typically required to prepare an evaluation. This time adds up.

People can also be uncomfortable giving a negative report about someone else—even when that person has glaring shortcomings or you assure them their responses will remain anonymous. The reviewers know that their report might result in no raise for (or even dismissal of) their colleague. But within an organization that’s committed to providing useful feedback and in which people understand the value of the 360-degree approach, soliciting others’ points of view can provide much more complete information on a direct report’s work than you, as an individual, possibly can. On the other hand, if an employee works with very few people or if asking for such feedback would not fit within your organization’s culture, 360-degree feedback may not add much to your own evaluation.

Your organization may have a set process for facilitating 360-degree feedback, but if it doesn’t, consider these tips for getting the most-useful information:

- Diversify your pool of respondents. Tap a number of peers, direct reports, and internal and external customers to provide input, rather than asking people from only one category or just one person from each category. Inviting a larger pool of participants means you’ll get a more complete picture, the respondents will feel more comfortable sharing their feedback knowing they’re not a lone identifiable voice, and your employee will be assured that you’ve worked to gather a broad, balanced view.

- Clarify that your purpose is constructive, not punitive. Explain to all involved—those giving feedback and those receiving it—that the purpose of the 360 review isn’t to amass criticism but to evaluate achievements and define areas for improvement.

- Request specific examples rather than just numeric ratings. If you’re asking about communication skills, you’ll learn much more from a response like “José answers all my questions clearly and patiently” than you will from a 5 out of 5 rating in communication.

- Ask probing questions. Dig deeper into people’s responses by asking thoughtful questions such as, How did this person contribute? What do you want this person to stop, start, and continue doing? What are their strengths as a collaborator, and what are their weaknesses?

Find additional information

Between your employee’s self-assessment, your own records, and the feedback of others, you should already be forming an objective picture of an individual’s performance. But consider other resources when assessing your employee’s work as well, including:

- The employee’s job description. You’re not just evaluating the quality of your employee’s work but determining how well they performed their specific job function.

- The person’s goals and development plan as defined in the last review or during the review period. When assessing performance against goals, it’s helpful to revisit those goals—taking into account any that may have changed over the course of the review period—to see if they’ve been successfully completed.

- Any documents from previous review sessions, prior evaluation forms, employment records, and other relevant material you may have on file.

After gathering your information, the next step is to pull it together into an overarching evaluation you’ll later share with your employee.

Assess Performance

To synthesize the information you’ve gathered, sift through it and begin noting common themes. Look for patterns and recurring threads, and just as you did when preparing to give feedback, focus on things that, if addressed, will make a difference in future performance. There’s no reason to rehash a onetime mistake, like the botched presentation six months ago that the employee underprepared for and that you’ve already discussed with them. On the other hand, if they’ve consistently presented poorly, and they’re still not sufficiently preparing despite multiple feedback discussions, you would be wise to address it in your formal appraisal.

Give equal consideration to positive results and to shortcomings when analyzing the overall picture. Has your direct report met the goals set for the review period? (It could be that their goals have changed since you initially set them a year ago, so take that into account.) It’s easiest to evaluate quantitative achievements—such as the numbers of presentations delivered, reports written, or apps developed—but to assess qualitative aspects of their work, focus on behaviors and supplement your evaluation with examples.

It can be difficult to assess performance against goals. Sure, if the goal is to assemble 150 widgets or generate mortgage loans equal to $3.5 million, it’s simple to make an accurate calculation. But few jobs are that clear-cut. What if measuring someone’s “output” requires evaluating how well they managed a team, influenced others, or helped people collaborate? In cases like these, assessment is more subjective. As a manager, you see only part of the employee’s work activity over the course of the year. The 360-degree feedback you collected will be especially helpful in assessing how they’re regarded by others and in gauging the scope and quality of their influence.

As you sift through your data, also consider how the employee has performed against behavioral expectations. Communication skills, for example, are critical for someone in a customer service role, just as coding skills are vital for a developer. Focus in on those behaviors that are most important for an employee’s success in their particular role. (Looking back at the job description or competency model for the position or level in the organization can help here.) Your organization may want you to focus on key behaviors or competencies or on how company values were demonstrated. Also take into account more-general attributes like initiative, cooperation and teamwork, efficiency, dependability, and improvement that may not be specific to the role or organization.

As you begin to draw conclusions about an employee’s performance, remember context. An individual’s performance depends, to varying degrees, on the situation in which they work. It’s not always fair or accurate to evaluate two colleagues in the same position on the same criteria, using the same scale or inflexible reference points. Consider situational factors in a call center, for example, where performance is assessed based on the dollar amount of charitable donations pledged. Different results can be caused by differences in the geographic regions or the populations of potential donors the employees are assigned. Such underlying factors may affect your direct report’s performance. It’s worth considering questions such as:

- What situational factors made it easier or harder for this person to achieve their goals?

- What systems, processes, structures, circumstances, or events helped or hindered this employee’s performance?

- How have I contributed to this employee’s success or performance problems?

Documenting the Performance Evaluation

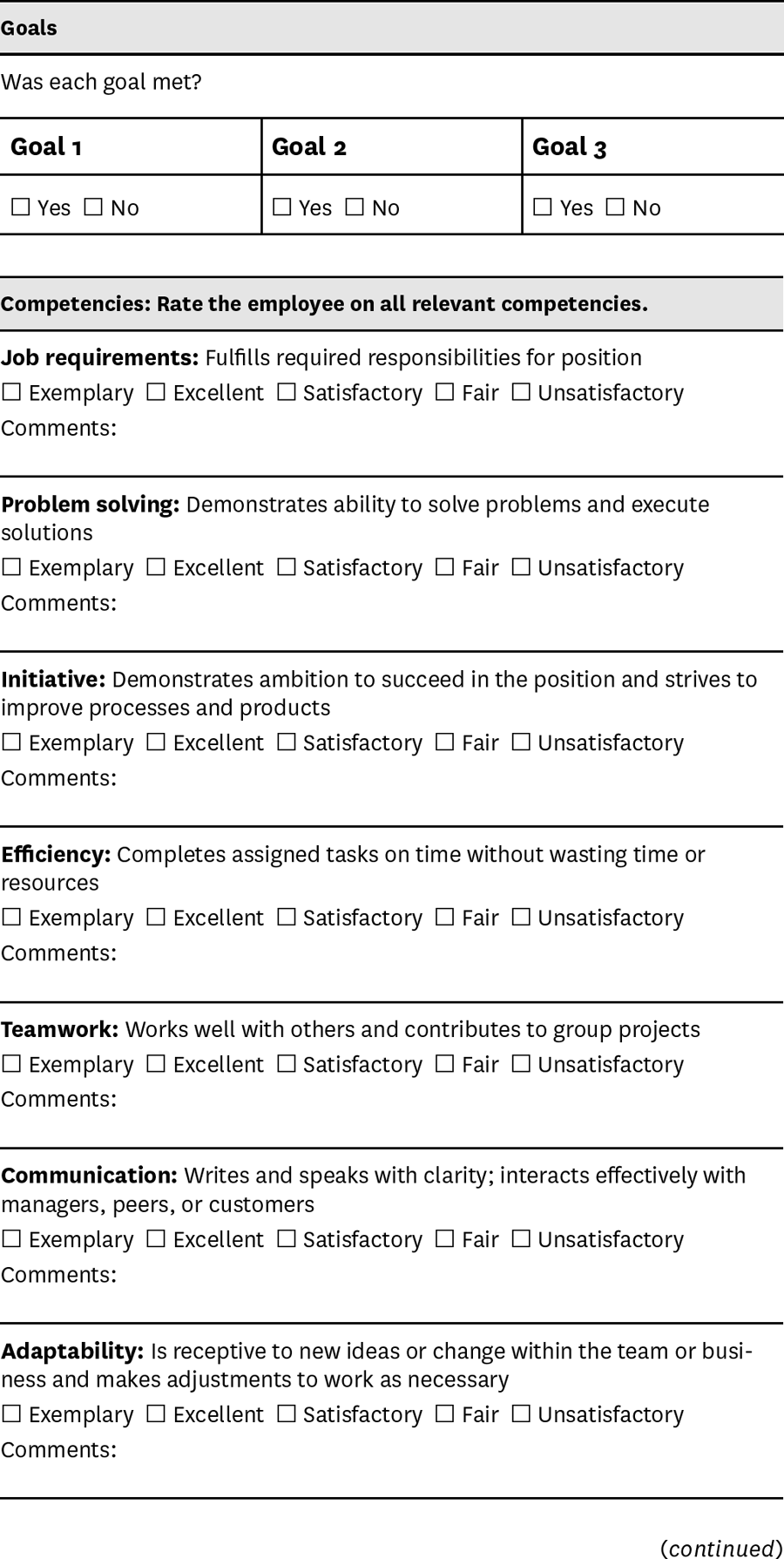

In many organizations, you’ll be required to document your impressions and feedback in a way that can be shared and saved. Your company may already have a set of questions to answer or a standard form to use. If not, you can create your own by adapting the performance evaluation form template in table 13-1 at the end of this chapter.

Record your observations about your employee’s job performance as objectively as possible, and support them with examples. Provide evidence of progress (or lack thereof) by connecting accomplishments with established goals. For example: “Derek increased sales by 12%, which exceeded his goal of 10%.” “Amelia reduced her error rate by 18%; her goal was 25%.” Including the background data informing your conclusions will help your direct report grasp the assessment criteria and recognize the evaluation as fair.

Your organization may require you to provide ratings—a general ranking of the employee’s performance or individual ratings of specific aspects of their performance. But a numeric value alone may not give your employee enough information to make improvements or continue good work. Instead, supplement your rating with qualitative examples, written and verbal observations, and comments that explain your choices. (See the sidebar “Navigating Ratings.”)

NAVIGATING RATINGS

Ratings used to be an established part of many organization’s performance appraisal processes. Despite movements away from this step, some organizations still require that managers rate or score their employees annually on a 5- (or sometimes 3- or 4-) point scale. And some of these require forced rankings, in which only 1 or 2 of 10 people can get the highest rating.

Some companies still find the process of rating valuable. At Facebook, for example, managers deliberate over those ratings in groups, to keep individual employees from being unduly punished or rewarded by managers who are hard or easy “graders.” Ratings are also used when making decisions about compensation.

But just as performance reviews are changing, so too is the practice of using performance ratings. Companies are discovering that ratings aren’t as effective as they hoped they’d be. For instance, in his HBR article “Performance Appraisal Reappraised,” Dick Grote described a workplace where nearly all annual ratings of 3,200 employees were positive. Not one person was rated “unsatisfactory”; just one had been deemed “marginal.” “Clearly, such uniformly glowing appraisals are useless in evaluating the relative merits of staff members,” Grote writes. The result is general “performance inflation” in which nearly everyone is rated above average—a statistical impossibility.

Ratings may no longer make sense in a changing work context. Many people work in teams that their direct managers may not observe, doing cross-functional work their managers may not even understand, let alone be able to assess accurately, so an immediate manager’s rating may not be correct or meaningful. As more people work in teams and as collaboration is increasingly valued, the traditional-forced rankingapproach also leads to competition, reducing the likelihood of open collaboration and damaging overall team-based performance. In response to these arguments, more and more organizations are ditching the use of ratings and forced distribution.

If you are required to rate your direct report, certainly do as your organization dictates, but keep in mind a few caveats. A five-point scale is not analogous to A–F grades in a school context. The majority of employees will get a 3, the middle rank. Some individuals may be disappointed with a 3 rating, thinking they’re merely average. In this context, a 3 means someone has hit their goal targets with solid, satisfactory performance. “In school, a C was mediocre,” Grote explains, “but a 3 in the working world means they’re meeting expectations. They’re shooting par.”1

In addition, combine your rating with specific comments and feedback that give the employee a clear understanding of why they got their rating and how their performance is aligning with their goals. If there isn’t space on your organization’s evaluation form, add a page to allow yourself room to explain the logic behind the rating, and discuss your rating during the meeting itself as well. Your employee will find your comments, observations, and qualitative examples valuable complements to a static quantitative score.

The more specific information you can provide to back up your conclusions, the more likely the employee will be to repeat and even improve on positive behaviors—and to correct negative ones. Use the most-telling examples to make your point in your written evaluation, and save the rest for your review session in case you need to support your judgment during the conversation. Examples should include:

- Details about what you observed. For instance, Theo, a customer service representative, has more than doubled the orders he’s filled over the past year now that he’s learned how to use a new customer database. Back that assessment up with detail in your write-up: “Last year Theo filled 15 orders per day. This year his average exceeded 30 per day. He also asks fewer questions now that he’s effectively using the customer database.”

- Supporting data, perhaps from 360-degree feedback. “Siobhan helped Theo learn how to use the new customer database, and she reports that he’s using it on a regular basis.”

- The impact on your team and organization. “After Theo learned how to use the new database, he no longer had to rely on colleagues to find out pertinent information. The whole team began fulfilling orders more quickly because they were answering fewer questions from him, which improved cash flow for the organization.”

Expressing your observations as neutral facts rather than judgments is particularly important when it concerns subpar results. “Theo received five complaints from extremely unsatisfied customers” is objective, nonjudgmental, and specific to a particular job requirement. Contrast that with a negative characterization that doesn’t describe actual behavior (“Theo doesn’t seem to care about customers”) or a vague judgment that fails to point to a specific skill he might improve (“Theo doesn’t know how to talk to difficult customers”).

When giving positive feedback, on the other hand, combine specific achievements with character-based praise. For example: “With the new accounts she generated, which delivered $1.25 million in business, Juliana exceeded the goal we set for her last July by 27%. Her creativity and perseverance drove her to look beyond the traditional client base; she researched new industries and networked at conferences to find new customers.” Acknowledging the traits and behaviors that made those results possible will show your direct report that you see them as an individual and recognize their unique contributions. Such praise can generate pride and boost motivation in your employee.

Supporting your assessment with specific examples, data, and details increases the likelihood that the employee will be able to absorb and learn from your feedback, and it also mitigates any possible legal ramifications in particularly egregious situations. If a person’s work is beginning to suffer, or if you suspect that you might need to dismiss someone due to poor performance, it’s vital that you document the individual’s behavior and the steps you’ve taken to correct it. As a rule of thumb, include in your evaluation only statements that you’d be comfortable testifying to in court. If you have any questions about legal ramifications, consult with your human resource manager or internal legal team.

Finally, write down the three things the employee has done best over the course of the year and the two areas that most need improvement. Distill your message down to one key idea—your overall impression of their performance, which is the single most important takeaway for your direct report. These few points will determine the overarching message that you want to convey in the review discussion, and having them documented will prevent you from forgetting any important details when you’re in the conversation.

NOTE

1. Quoted in Rebecca Knight, “Delivering an Effective Performance Review,” HBR.org, November 3, 2011, https://hbr.org/2011/11/delivering-an-effective-perfor.