Accelerate!

by John P. Kotter

PERHAPS THE GREATEST CHALLENGE business leaders face today is how to stay competitive amid constant turbulence and disruption.

Any company that has made it past the start-up stage is optimized for efficiency rather than for strategic agility—the ability to capitalize on opportunities and dodge threats with speed and assurance. I could give you 100 examples of companies that, like Borders and RIM, recognized the need for a big strategic move but couldn’t pull themselves together to make it and ended up sitting by as nimbler competitors ate their lunch. The examples always play out the same way: An organization that’s facing a real threat or eyeing a new opportunity tries—and fails—to cram through some sort of major transformation using a change process that worked in the past. But the old ways of setting and implementing strategy are failing us.

We can’t keep up with the pace of change, let alone get ahead of it. At the same time, the stakes—financial, social, environmental, political—are rising. The hierarchical structures and organizational processes we have used for decades to run and improve our enterprises are no longer up to the task of winning in this faster-moving world. In fact, they can actually thwart attempts to compete in a marketplace where discontinuities are more frequent and innovators must always be ready to face new problems. Companies used to reconsider their strategies only rarely. Today any company that isn’t rethinking its direction at least every few years—as well as constantly adjusting to changing contexts—and then quickly making significant operational changes is putting itself at risk. But, as any number of business leaders can attest, the tension between needing to stay ahead of increasingly fierce competition and needing to deliver this year’s results can be overwhelming.

What to do, then?

We cannot ignore the daily demands of running a company, which traditional hierarchies and managerial processes can still do very well. What they do not do well is identify the most important hazards and opportunities early enough, formulate creative strategic initiatives nimbly enough, and implement them fast enough.

The existing structures and processes that together form an organization’s operating system need an additional element to address the challenges produced by mounting complexity and rapid change. The solution is a second operating system, devoted to the design and implementation of strategy, that uses an agile, networklike structure and a very different set of processes. The new operating system continually assesses the business, the industry, and the organization, and reacts with greater agility, speed, and creativity than the existing one. It complements rather than overburdens the traditional hierarchy, thus freeing the latter to do what it’s optimized to do. It actually makes enterprises easier to run and accelerates strategic change. This is not an “either or” idea. It’s “both and.” I’m proposing two systems that operate in concert.

The strategy system has its roots in familiar structures, practices, and thinking. Many start-ups, for example, are organized more as networks than as hierarchies, because they need to be nimble and creative in order to grab opportunities. Even in mature organizations, informal networks of change agents frequently operate under the hierarchical radar. What I am describing also echoes much of the most interesting management thinking of the past few decades—from Michael Porter’s wake-up call that organizations need to pay attention to strategy much more explicitly and frequently, to Clayton Christensen’s insights about how poorly traditionally organized companies handle the technological discontinuities inherent in a faster-moving world, to recent work by the Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman (Thinking, Fast and Slow, 2011) describing the brain as two coordinated systems, one more emotional and one more rational.

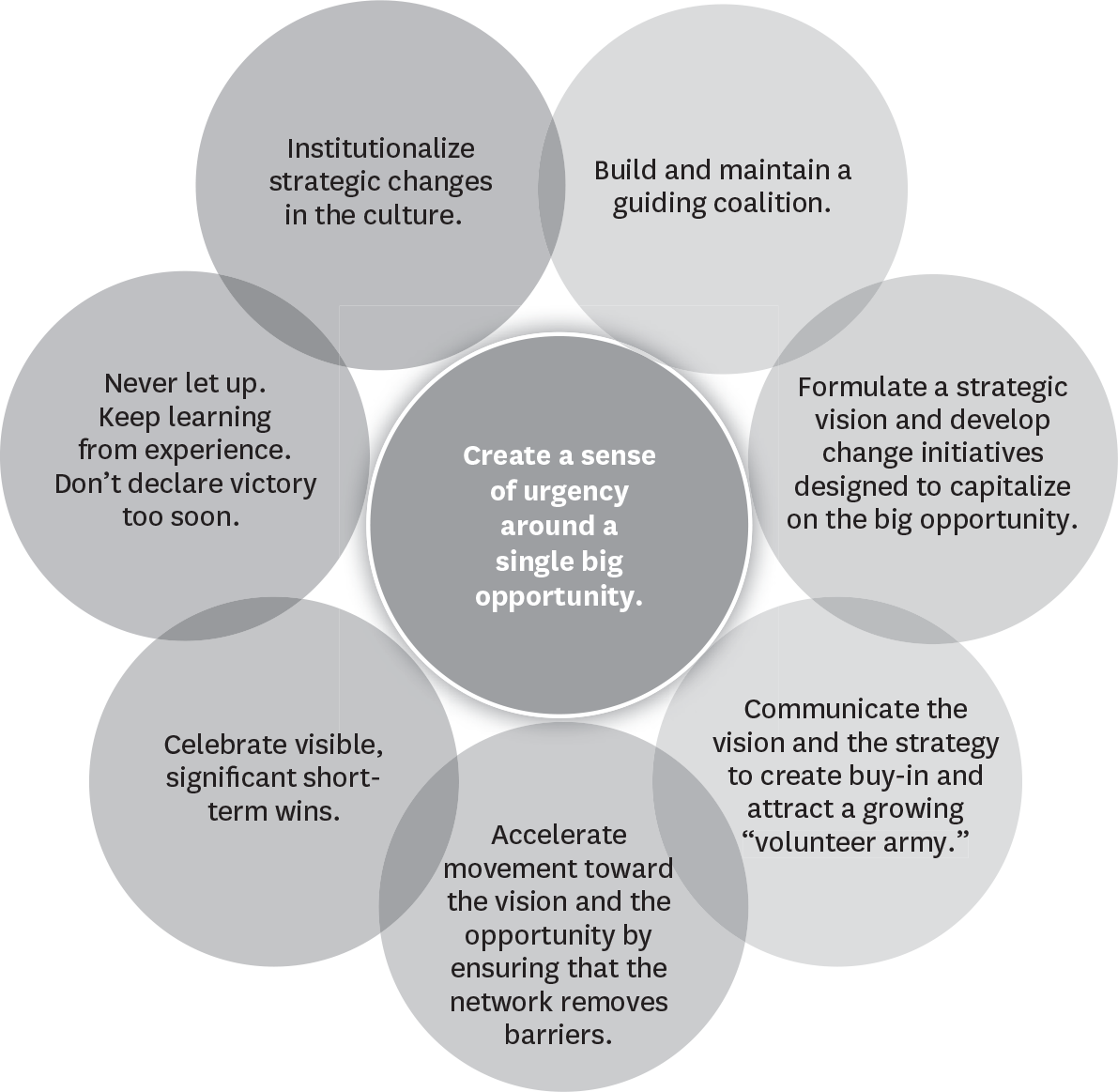

The new strategy system also expands on the eight-step method I first documented 15 years ago (in Leading Change), while studying successful large-scale change: establishing a sense of urgency, creating a guiding coalition, developing a change vision, communicating the vision for buy-in, empowering broad-based action, generating short-term wins, never letting up, and incorporating changes into the culture.

There are three main differences between those eight steps and the eight “accelerators” on which the strategy system runs: (1) The steps are often used in rigid, finite, and sequential ways, in effecting or responding to episodic change, whereas the accelerators are concurrent and always at work. (2) The steps are usually driven by a small, powerful core group, whereas the accelerators pull in as many people as possible from throughout the organization to form a “volunteer army.” (3) The steps are designed to function within a traditional hierarchy, whereas the accelerators require the flexibility and agility of a network.

For a long time companies could invest all their energy and resources in doing one new thing very well: They might spend two years setting up a large IT project that required many changes and then, after a long pause, spend five years developing a propensity for risk-taking in the product development function. They could put the eight-step process to work and then pack it away until it was needed again. But that methodology has a hard time producing excellent results in a faster-changing world.

Today companies must constantly seek competitive advantage without disrupting daily operations. Sure, industries face varying levels of turmoil, but what smart company isn’t worried about being disintermediated, out-Googled, or otherwise made irrelevant—and how many are successfully doing something about it? In fact, the whole notion of “strategy”—a word that is now used loosely to cover sporadic planning around what businesses to be in and important policies concerning how to compete in those businesses—has to evolve. Strategy should be viewed as a dynamic force that constantly seeks opportunities, identifies initiatives that will capitalize on them, and completes those initiatives swiftly and efficiently. I think of that force as an ongoing process of “searching, doing, learning, and modifying,” and of the eight accelerators as the activities that inform strategy and bring it to life. The network and the accelerators can serve as a continuous and holistic strategic change function—one that accelerates momentum and agility because it never stops. They impart a kind of strategic “fitness”: The more the organization exercises its strategy skills, the more adept it becomes at dealing with a hypercompetitive environment. The network and the hierarchy, functioning as a dual operating system, can produce more wealth, better products and services, and a more exciting place to work in an era of exponential change.

The Limits of Hierarchy and Conventional Change Management

Hierarchies are useful. They let us sort work into departments, product divisions, regions, and the like with expertise, time-tested procedures, and clear reporting relationships and accountability so that we can do what we know how to do with efficiency, predictability, and effectiveness. Hierarchies are directed by familiar managerial processes for planning, budgeting, defining jobs, hiring and firing, and measuring results.

We have learned how to improve our hierarchy-based businesses. We launch initiatives to take on new tasks and improve performance on old ones. We have learned how to identify new problems, find and analyze data in a dynamic marketplace, build business cases for change, and gain approval. We have learned to execute by adding task forces, tiger teams, project-management and change-management departments, executive sponsors for new initiatives, and associated measurement and incentive schemes. We can do this while taking care of the day-to-day work of the organization because this change methodology is easily accommodated by the hierarchical structure and basic managerial processes. It works especially well if we make the structure less bureaucratic, with fewer layers and fewer questionable rules, and give more discretion to people who sit lower in the hierarchy. This methodology can deal with both tactical and strategic issues in a changing world—but only up to a point.

The old methodology simply can’t handle rapid change. Hierarchies and standard managerial processes, even when minimally bureaucratic, are inherently risk-averse and resistant to change. Part of the problem is political: Managers are loath to take chances without permission from superiors. Part of the problem is cultural: People cling to their habits and fear loss of power and stature—two essential elements of hierarchies. And part of the problem is that all hierarchies, with their specialized units, rules, and optimized processes, crave stability and default to doing what they already know how to do. (These characteristics are even more pronounced when you pile one hierarchy on top of another to create a matrixed organization.)

Moreover, strategy implementation methodologies, hung on the hierarchical spine, are not up to the challenge of managing speedy transformation. Change management typically relies on tools—such as diagnostic assessments and analyses, communications techniques, and training modules—that can be invaluable in helping with episodic problems for which there are relatively straightforward solutions, such as implementing a well-tested financial reporting system. These approaches are effective when it is clear that you need to move from point A to a well-defined point B; the distance between the two is not galactic; and pushback from employees will not prove to be herculean. Change-management processes supplement the system we know. They can slide easily into a project-management organization. They can be made stronger or faster by adding more resources, more-sophisticated versions of the same old methods, or smarter people to drive the process—but again, only up to a point. After that point, using this approach to launch strategic initiatives that ask an organization to absorb more change faster can create confusion, resistance, fatigue, and higher costs.

Complementary Systems

Mounting complexity and rapid change create strategic challenges that even a souped-up hierarchy can’t handle. That’s why the dual operating system—a management-driven hierarchy working in concert with a strategy network—works so remarkably well.

At the heart of the dual operating system are five principles:

Many change agents, not just the usual few appointees. To move faster and further, you need to pull more people than ever before into the strategic change game, but in a way that is economically realistic. That means not large numbers of full-time or even part-time appointments but volunteers. And 10% of the managerial and employee population is both plenty and possible.

A want-to and a get-to—not just a have-to—mind-set. You cannot mobilize voluntary energy and brainpower unless people want to be change agents and feel they have permission to do so. The spirit of volunteerism—the desire to work with others for a shared purpose—energizes the network.

Head and heart, not just head. People won’t want to do a day job in the hierarchy and a night job in the network—which is essentially how a dual operating system works—if you appeal only to logic, with numbers and business cases. You must appeal to their emotions, too. You must speak to their genuine desire to contribute to positive change and to take an enterprise in strategically smart ways into a better future, giving greater meaning and purpose to their work.

Much more leadership, not just more management. At the core of a successful hierarchy is competent management. A strategy network, by contrast, needs lots of leadership, which means it operates with different processes and language and expectations. The game is all about vision, opportunity, agility, inspired action, and celebration—not project management, budget reviews, reporting relationships, compensation, and accountability to a plan.

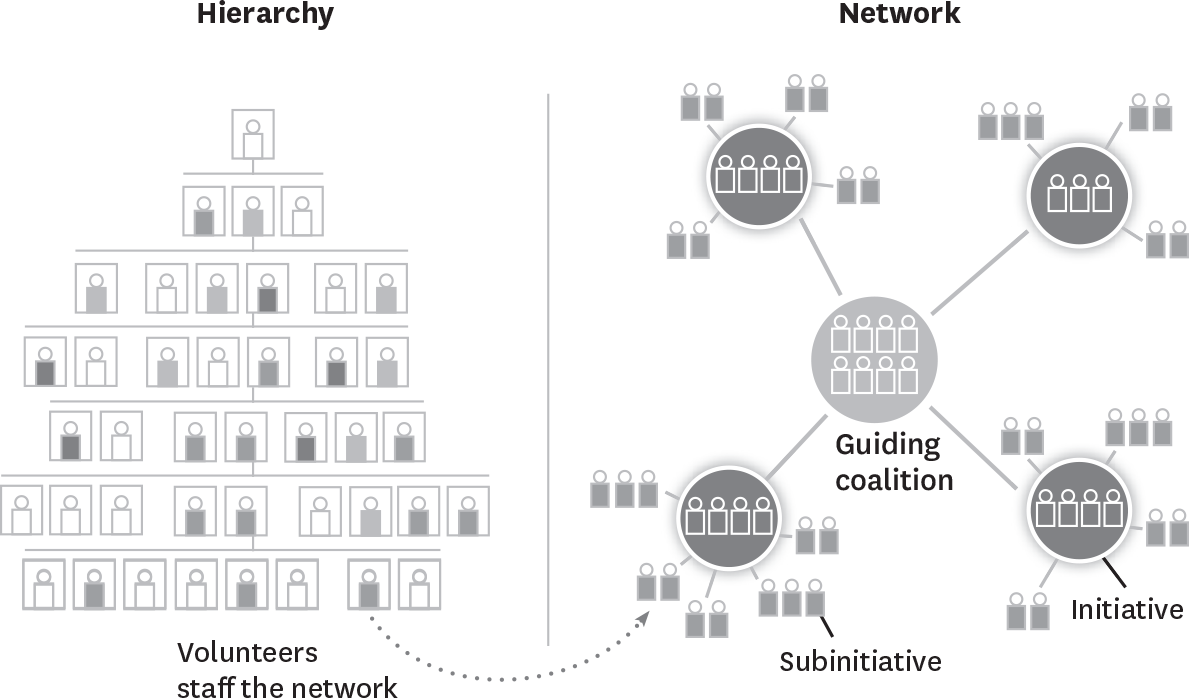

Two systems, one organization. The network and the hierarchy must be inseparable, with a constant flow of information and activity between them—an approach that works in part because the volunteers in the network all work within the hierarchy. (See the exhibit “Two structures, one organization.”) The dual operating system is not two supersilos, like the old Xerox PARC (an amazing strategic innovation machine) and Xerox (which pretty much ignored PARC and the commercial opportunities it uncovered).

Two structures, one organization

Traditional hierarchies and processes, which together form an organization’s “operating system,” do a great job of handling the operational needs of most companies, but they are too rigid to adjust to the quick shifts in today’s marketplace. The most agile, innovative companies add a second operating system, built on a fluid, networklike structure, to continually formulate and implement strategy. The second operating system runs on its own processes (see “The eight accelerators,” later in this chapter) and is staffed by volunteers from throughout the company.

Governed by these principles, the strategy network can be incredibly flexible and adaptable; the accelerators can drive problem solving, collaboration, and creativity; and the people doing this work—the volunteer army—will be focused, committed, and passionate.

The network is like a solar system, with a guiding coalition as the sun, strategic initiatives as planets, and subinitiatives as moons (or even satellites). This structure is dynamic: Initiatives and subinitiatives coalesce and disband as needed. Although a typical hierarchy tends not to change from year to year, the network can morph with ease. In the absence of bureaucratic layers, command-and-control prohibitions, and Six Sigma processes, this type of network permits a level of individualism, creativity, and innovation that not even the least bureaucratic hierarchy can provide. Populated with employees from all across the organization and up and down its ranks, the network liberates information from silos and hierarchical layers and enables it to flow with far greater freedom and accelerated speed.

The hierarchy differs from almost every other hierarchy today in one very important way: All the junk ordinarily pasted on it for tackling big strategic initiatives—work streams, tiger teams, strategy departments—has been shifted over to the network. That leaves the hierarchy less encumbered and able to perform better and faster what it is designed for: doing today’s job well, making incremental changes to further improve efficiency, and handling the small initiatives that help a company deal with predictable adjustments such as routine IT upgrades.

The strategy network meshes with the hierarchy as an equal. It is not a super task force that reports to some level in the hierarchy. It is seamlessly connected to and coordinated with the hierarchy in a number of ways, chiefly through the people who populate both systems. Still, the organization’s leaders play an important role in launching and maintaining the network: the C-suite or executive committee must create it (more on that later) and explicitly bless and support it. The network cannot be viewed as a rogue operation. It must be treated as a legitimate part of the organization, or the hierarchy will crush it.

The Eight Accelerators

These are the processes that enable the strategy network to function:

1. Create a sense of urgency around a single big opportunity

This is absolutely critical to heightening the organization’s awareness that it needs continual strategic adjustments and that they should always be aligned with the biggest opportunity in sight. Urgency starts at the top of the hierarchy, and it is important that executives keep acknowledging and reinforcing it so that people will wake up every morning determined to find some action they can take in their day to move toward that opportunity.

Sufficient urgency around a strategically rational and emotionally exciting opportunity is the bedrock upon which all else is built. In my original work 15 years ago, I found that ridding an organization of complacency was important. In my more recent work, I’ve seen ongoing urgency emerge as a strong competitive advantage. It can galvanize a volunteer army and keep the dual operating system in good working order. It moves managers to focus on opportunities and allow the network to grow for the benefit of the organization. Without an abiding sense of urgency, no chance of creating a grander business will survive.

For clients, my team has begun by having the executive committee take a first pass at articulating the strategic opportunity. This makes sense because its members are in a position to see the big picture and because their role in nurturing the dual structure is vital—particularly in the early days, when it is most vulnerable to the forces of resistance. (For the story of how one sales executive at a technology firm created urgency, see the sidebar “The Dual Operating System in Practice.”)

The eight accelerators

The processes that enable the strategy network to function

2. Build and maintain a guiding coalition

The core of a strategy network is the guiding coalition (GC), which is made up of volunteers from throughout the organization. In my work with clients, people fill out applications to be on the GC. With a sufficient sense of urgency, you may get 10 times as many applications as there are roles in the network’s core.

The GC is selected to represent each of the hierarchy’s departments and levels, with a broad range of skills. It must be made up of people whom the leadership trusts, and must include at least a few outstanding leaders and managers. This ensures that the GC can gather and process information as no hierarchy ever could.

All members of the GC are equal; no internal hierarchy slows down the transfer of information. The coalition can see inside and outside the enterprise, knows the details and the big picture, and uses all this information to make good enterprisewide decisions about which strategic initiatives to launch and how best to do so. The social dynamics of the GC may be uncomfortable at first, but once a team learns how to operate well, most members seem to love being part of it.

3. Formulate a strategic vision and develop change initiatives designed to capitalize on the big opportunity

The vision will serve as a strategic true north for the dual operating system. A well-formulated vision is focused on taking advantage of a big make-or-break opportunity. (If no such opportunity exists, because you operate in a rare pocket of competitive stability, you may not need this system quite yet. But keep your eyes open: That situation won’t last.) The right vision is feasible and easy to communicate. It is emotionally appealing as well as strategically smart. And it gives the GC a picture of success and enough information and direction to make consequential decisions on the fly, without having to seek permission at every turn.

In creating one company’s vision statement, the guiding coalition sought input from top management, a consultant’s report, and colleagues throughout the organization. The vision statement described what the sales group, which was dealing with market losses, could look like in a year if it accelerated toward a big opportunity. It outlined pragmatic goals but framed them with emotional resonance, using words such as “proud,” “passionate,” and “admired.” As a result, the group vowed to work better with partners, double growth in emerging markets, innovate constantly, and halve the time it took to make decisions.

Next the GC identified the five strategic initiatives that its members deemed critical to achieving the vision and that they wanted very much to work on, including “innovation in attacking growing markets.” Inspired by the vision and guided by the initiatives that flowed logically from it, everyone within the network became an author of strategic change. That’s very powerful.

To keep the two parts of a dual operating system connected and aligned, we have found, the GC must show a draft of the vision and initiatives to the organization’s executive committee for comments. A well-functioning GC will treat the committee’s comments as highly valuable input but won’t automatically accept them as commands.

4. Communicate the vision and the strategy to create buy-in and attract a growing volunteer army

A vividly formulated, high-stakes vision and strategy, promulgated by a GC in ways that are both memorable and authentic, will prompt people to discuss them without the cynicism that often greets messages cascading down the hierarchy. Done right, with creativity, such communications can go viral, attracting employees who buy in to the ambition of the message and begin to share a commitment to it.

This point tends to prompt skepticism from people who have seen attempts to motivate a workforce fail. But if the right messages are sent from a passionate GC to colleagues who feel a sense of urgency, the volunteer army will start to gather. I’ve seen it happen. Motivation is an issue when people are forced to work in boxes within a hierarchy where workers become bored, new ideas aren’t welcome, and managers aren’t effective. And it does not take many volunteers to get a network launched: Again, 10% of the total employee population will do. That’s 500 people in an organization of 5,000.

5. Accelerate movement toward the vision and the opportunity by ensuring that the network removes barriers

Perhaps a sales rep has gotten customer complaints about bureaucratic hang-ups. He doesn’t know how to fix the problem and doesn’t have time to think about it. Someone in the network gets wind of this and says, “I’ve seen that. I volunteer. I’ll put together a group and attack it.” That person writes up a description and sends it out to the volunteer army, and five people immediately step forward. They set up a call to begin learning why this is happening, figuring out how to remove the barrier, and designing a solution—a better CRM system, perhaps. The team probably includes someone from IT who has technical expertise and can help identify where the money for the new system might come from. The team works with additional volunteers who have relevant information—from whatever quarter may be germane—to act quickly and efficiently. The time between the first call and this point might be two weeks—a model of accelerated action. The network team settles on a practical solution that properly supports the sales team. Then its members take their thinking to the CIO, who gives feedback and may offer the budget and the resources.

Design and implementation occur in the network and are instituted within the hierarchy. And if the network is truly operating hand-in-glove with the hierarchy, the people in the hierarchy are champing at the bit to get the new CRM system.

6. Celebrate visible, significant short-term wins

A strategy network’s credibility won’t last long without confirmation that its decisions and actions are actually benefiting the organization. Skeptics will erect obstacles unless they see proof that the dual operating system is creating real results. And people have only so much patience, so proof must come quickly. To ensure success, the best short-term wins should be obvious, unambiguous, and clearly related to the vision. Celebrating those wins will buoy the volunteer army and prompt more employees to buy in. Success breeds success.

If wins are not forthcoming, that in itself is useful feedback: Something is wrong. A committed GC, with many eyes and ears to take in the reality of the situation and with no status or territory to protect, can quickly tweak either the decisions it has made or the methods used for implementing those decisions.

7. Never let up. Keep learning from experience. Don’t declare victory too soon

Organizations must continue to carry through on strategic initiatives and create new ones, to adapt to shifting business environments, and thus to enhance their competitive positions. When an organization takes its foot off the gas, cultural and political resistance arise.

Here, again, is why urgency is so central to the strategy part of the dual operating system. It keeps people going. If it is weak to begin with, or neglected, the volunteer army’s determination will flag, and the temptation to slow down or stop will become irresistible. The volunteers will start focusing on their work in the hierarchy, and the hierarchy will dominate once more.

8. Institutionalize strategic changes in the culture

No strategic initiative, big or small, is complete until it has been incorporated into day-to-day activities. A new direction or method must sink into the very culture of the enterprise—and it will do so if the initiative produces visible results and sends your organization into a strategically better future.

The Volunteer Army

The members of the volunteer army also help make the daily business of the organization hum; they’re not a separate group of consultants, new hires, or task force appointees. They have organizational knowledge, relationships, credibility, and influence. They understand the need for change—they are often the first to see threats or opportunities—and have the zeal to implement it.

It is vital that this army be made up of individuals who bring energy, commitment, and genuine enthusiasm. They are not a bunch of grunts carrying out orders from the brass. Rather, they are change leaders. Whereas hierarchies require management to maintain an efficient status quo, networks demand leadership from every individual within them.

People who have never seen this sort of dual operating system work often worry, quite logically, that a bunch of enthusiastic volunteers might create more problems than they solve—by, for example, running off and making not very thoughtful decisions and disrupting daily operations. Here is where the very specific details built into the network and the accelerators come into play. This second system not only creates the army but guides the volunteers with a structure and processes that create a powerful, smart, and increasingly needed strategic force.

In organizations where the volunteer army has really taken hold, individuals have told me that the rewards are tremendous—though rarely monetary. They talk about the fulfillment they get from pursuing a mission they believe in. They appreciate the chance to collaborate with a broader array of people than they ever could have before. A number of them say that their strategy work led to increased visibility across the organization and to bigger jobs in the hierarchy. And their managers appreciate how the volunteers develop professionally. In June 2012 I got this e-mail message from a client in Europe: “I can’t believe how quickly this second operating system gives growth to real talents within the organization. Once people feel ‘Yes, I can do it!’ they also start faster growth in their regular jobs in the hierarchy, which helps make today’s operations more effective.”

Building Momentum

Over the past three years I’ve aided eight organizations, private and public, in building dual operating systems, and the challenges have been fairly predictable. One is how to ensure that the two parts work together and don’t drift apart. Here it is essential that the GC and the executive committee maintain close communication. Another is how to build momentum: Most important is to communicate wins from the very start. Probably the biggest challenge is how to make people who are accustomed to a control-oriented hierarchy believe that a dual system is even possible. Again, this is why a rational and compelling sense of urgency around a big strategic opportunity is so important. Once it has been sparked, mobilizing the GC and putting the remaining accelerators in motion happens almost organically.

A dual operating system doesn’t start fully formed and doesn’t require a sweeping overhaul of the organization. It grows over time, accelerates action over time, and takes on a life of its own that seems to differ from company to company in the details. It can start with small steps. Version 1.0 of a strategy network may arise in only one part of an enterprise. After it becomes a powerful accelerating force there, it can expand throughout the organization. Version 1.0 may play little or no role in strategy formulation but be involved, rather, in implementation. It may feel at first more like a big employee-engagement exercise that does, indeed, produce a much bigger payoff for the same size payroll. But the network and the accelerators evolve, and momentum comes faster than you might expect.

A Summary and a Prediction

Because a dual operating system evolves, it doesn’t jolt the organization the way sudden dramatic change does. It doesn’t require the organization to build something gigantic and then flick a switch to get it going. Think of it as a vast, purposeful expansion in scale, scope, and power of the smaller, informal networks that accomplish tasks faster and cheaper than hierarchies can.

The system offers a solution to problems we have known about for some time. People have been writing for at least 20 years about the increasing speed of business and the need for organizations to be quicker and much more agile. But who has been able to pull that off? The situation won’t be improved by tweaking the usual methodology or adding turbochargers to a single hierarchical system. That’s like trying to rebuild an elephant so that it can be both an elephant and a panther. It’s never going to happen.

People have been writing for 50 years about unleashing human potential and directing the energy to big business challenges. But who, outside the world of start-ups, has succeeded? So few do because they’re working within a system that basically asks most people to shut up, take orders, and do their jobs in a repetitive way.

People have been talking for a quarter of a century about the need for more leaders, because an organization’s top two or three executives can no longer do it all. But very few jobs in traditional hierarchical organizations provide the information and the experience needed to become a leader. And the solutions available—courses on leadership, for example—are wholly inadequate, because most development of complex perspectives and skills happens on the job, not in the classroom.

People have been grumbling for years about the strategy consulting industry, whose reports fail to solve the problem of finding and implementing strategies to better fit a changing environment. A consultant’s report—all thought and little heart, forecasting where you can flourish in two or five or 10 years, produced by smart outsiders, and acted on in a linear way by a limited number of appointed people—has little or no chance of success in a faster-moving, more uncertain world.

The inevitable failures of single operating systems hurt us now. They are going to kill us in the future. The 21st century will force us all to evolve toward a fundamentally new form of organization. I believe that I have basically described that form here. We still have much to learn. Nevertheless, the companies that get there first, because they act now, will see immediate and long-term success—for shareholders, customers, employees, and themselves. Those that lag will suffer greatly, if they survive at all.

Originally published in November 2012. Reprint R1211B