Chapter 3. The Hidden Costs of Absenteeism

Call centers (whether in one physical location or a remote configuration of workers from home) are finely tuned operations whose economic outcomes often depend on very precise optimization of staff levels against anticipated call volume.1 Other similar operations include retail stores and restaurants. When an employee is unexpectedly absent in a call center, it may mean that calls are missed, that other workers must adjust and will do their jobs less effectively, or that a buffer of extra workers must be employed or kept on call to offset the effects of absence. What is it worth to reduce such absences? What costs can be avoided, and what is the likely effect of organizational investments designed to reduce the need or the motivation of employees to be absent?

A first reaction might be, “We should cut absences to zero, because employees should be expected to show up when they are scheduled.” However, as discussed in this chapter, the causes of absence are highly varied, so cutting absence requires a logical approach to understanding why it happens. In fact, an increasing number of jobs have no absenteeism, because they have no real work schedule! They are project based and thus are accountable only for the ultimate results of their work. In such jobs, employees can work whatever schedule they want, as long as they produce the needed results on time. For many jobs, however, adhering to the work schedule is an important contribution to successful operations.

Sometimes it is cost-effective just to tolerate the absence level and allow work to be missed or employees to adjust. In other situations, it is very cost-effective to invest in ways to reduce absence. It depends on the situation.

Particularly when employees are absent because they are taking unfair advantage of company policies (such as claiming more sick leave than is appropriate), it is tempting to conclude that such absence must be reduced even if it takes a significant investment. It seems “unfair” to tolerate it. Upon further reflection, however, it’s clear that absence is like any other risk factor in business. How we address it should be based on a logical and rational decision about costs and benefits. We need a logical understanding of the consequences of absence to make those decisions. We provide that logic in this chapter.

What Is Employee Absenteeism?

Let us begin our treatment by defining the term absenteeism. Absenteeism is any failure to report for or remain at work as scheduled, regardless of reason. The use of the words as scheduled is significant, for this automatically excludes vacation, personal leave, jury-duty leave, and the like. A great deal of confusion can be avoided simply by recognizing that if an employee is not on the job as scheduled, he or she is absent, regardless of cause. We focus here on unscheduled absence because it tends to be the most disruptive and costly of the situations when an employee is not at work. The employee is not available to perform his or her job as expected. This often means that the work is done less efficiently by another employee or is not done at all. Scheduled or authorized absences (such as vacations and holidays) are more predictable. This chapter describes in detail the potentially costly consequences of absence.

Although the definition of absenteeism might leave little room for interpretation, the concept itself is undergoing a profound change, largely as a result of the time-flexible work that characterizes more and more jobs in our economy. A hallmark of such work is that workers are measured not by the time they spend, but by the results they achieve. Consider, for example, the job of a computer programmer whose sole job is to write or evaluate computer code. The programmer is judged by whether the program runs efficiently and whether it does what it is supposed to do reliably. It doesn’t matter when the programmer works (9 to 5 or midnight to dawn) or where the programmer works (at the office or at home).

If the work schedule doesn’t matter and workers operate virtually, does the concept of absenteeism still have meaning? In the U. S., the number of people who work from remote locations at least once a month rose 39 percent from 2006 to 2008, to an estimated 17.2 million.2 If workers never “report” for work, and if they are allowed to vary their work time, and are accountable only in terms of results, the concept of absenteeism ceases to be relevant. Many teleworkers fit this category. Many others do not, however, for they are expected to be available during a core time to participate in activities such as chats with coworkers or the boss, conference calls, or webcasts.

In short, absenteeism may still be a relevant concept in a world of telework. Measurement must evolve from traditional absence, where people are colocated, to the concept of being present in a virtual world. If a teleworker is surfing the web during a conference call, is he or she “absent”?

In fact, many of the effects of traditional absenteeism are still relevant, even if traditional accounting systems would not capture them. Before attempting to assess the costs of employee absenteeism, therefore, it is important to identify where absenteeism is a relevant concept.

Of course, absenteeism remains relevant for the millions of workers who are scheduled to report to a central location, such as a factory, an office, a retail store, or a call center. In fact, as noted earlier, even those who can work from home in a call center, such as Jet Blue’s airline reservations agents, have to be at home and on the phone at certain times to make the scheduling work. More broadly, the growing importance of location-specific or time-specific customer service operations, such as the millions of employees who are engaged in repairs (of cars, appliances, or plumbing systems) or delivery (of pizzas, newspapers, or mail), makes employee absence a very real and potent issue for many organizations.

At the outset, let us be clear about what this chapter is and is not. It is not a detailed literature review of the causes of absenteeism, such as local unemployment, the characteristics of jobs,3 gender, age, depression, smoking, heavy drinking, drug abuse, or lack of exercise.4 Nor is it a thorough treatment of the noneconomic consequences of absenteeism, such as the effects on the individual absentee, coworkers, managers, the organization, the union, or the family. Instead, the primary focus in this chapter is on the economic consequences of absenteeism and on methods for managing absenteeism and sick-leave abuse in work settings where those concepts remain relevant and meaningful.

The Logic of Absenteeism: How Absenteeism Creates Costs

The logic of absenteeism begins by identifying its causes and consequences. To provide some perspective on the issue, we begin our next section by citing some overall direct costs and data that show the incidence of employee absenteeism in the United States and Europe. Then we focus more specifically on causes and consequences, and we present a high-level logic diagram that may serve as a “mental map” for decision makers to help them understand the logic of employee absenteeism.

Direct Costs and the Incidence of Employee Absenteeism

How much does unscheduled employee absenteeism cost? According to a 2008 Mercer survey of 465 companies, if one excludes planned absences (vacations, holidays), the total direct and indirect costs consume 9 percent of payroll.5 Direct costs include actual benefits paid to employees (such as sick leave and short- and long-term disability), while indirect costs reflect reduced productivity (delays, reduced morale of coworkers, and lower productivity of replacement employees).

Thus, a 1,000-employee company that averages $50,000 in salary per employee would have an annual payroll of $50 million. Nine percent of that is $4.5 million, or about $4,500 per employee when direct and indirect costs are both considered.

In the United Kingdom, 2008 absences were also costly, as the following figures demonstrate:6

• Across all companies, £13.2 billion ($19.8 billion) was paid out to staff who were absent and to other employees to cover for absent staff.

• The average cost of sickness was £517 per employee ($775).

• Each worker took an average of 6.7 days in sickness each year.

• Figures for average days off were higher in the public sector (9) than in the private sector (5.8).

• The total days lost due to absenteeism each year in the United Kingdom are 172 million, of which 21 million are thought to be nongenuine (used to extend weekends, holidays, or for special events such as birthdays and football games). These cost employers an additional £1.6 billion ($2.4 billion).

In 2009, the average employee in the United States missed 1.7 percent of scheduled work time, or an average of 3.3 unscheduled absences per year.7

Causes

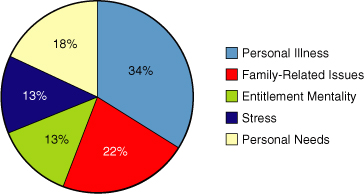

In the United Kingdom, the reasons given for absence are widespread but generally fall into one of three categories: illness, time off to deal with home and family responsibilities, and medical appointments.8 In the United States, the leading cause of absenteeism is personal illness (35 percent), while 65 percent of absences are due to other reasons.9 In the private sector, however, fully 40 percent of employees do not receive sick pay.10 Figure 3-1 details the five most common causes cited by employees for being absent.

Figure 3-1. Why are workers absent?

Consequences

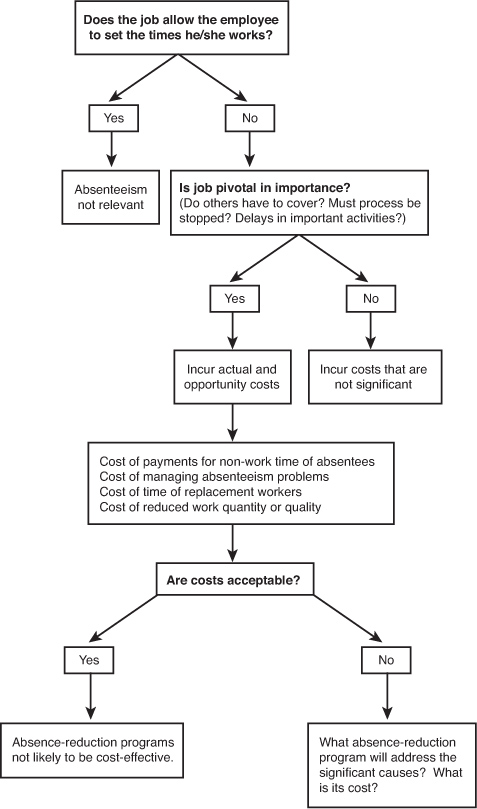

The decision to invest in reducing absence requires that one consider the payoff. What consequences of absence will be avoided? We’ve noted that absence occurs only in jobs where employees are required to be at work, or available to be contacted remotely, at specified times. So the consequences of absence directly relate to the fact that an employee is unavailable to work as scheduled. Absence is more “pivotal” (changes in absence affect economic and strategic success more) when the situation has these characteristics:

• Others have to perform the work of the absent employee.

• A process must be stopped because of the absence of an employee.

• Activities must occur at a certain time and are delayed or missed because an employee is absent.

Categories of Costs

At a general level, four categories of costs are associated with employee absenteeism. We elaborate on each of these categories more fully in the sections that follow. For the moment, let us describe these categories as follows:

• Costs associated with absentees themselves (employee benefits and, if they are paid, wages)

• Costs associated with managing absenteeism problems (costs associated with supervisors’ time spent dealing with operational issues caused by the failure of one or more employees to come to work)

• The costs of substitute employees (for example, costs of overtime to other employees or costs of temporary help)

• The costs of reduced quantity or quality of work outputs (for example, costs of machine downtime, reduced productivity of replacement workers, increased scrap and reworks, poor customer service)

In computing these costs, especially the costs of managing absenteeism problems and revenues foregone, researchers commonly use the fully loaded cost of wages and benefits as a proxy for the value of employees’ time. However, as we cautioned in Chapter 2, “Analytical Foundations of HR Measurement,” although this is very common, keep in mind that it is only an approximation; the assumption that total pay equals the value of employee time is not generally valid.

Figure 3-2 presents an illustration of the ideas we have examined thus far.

Figure 3-2. The logic of employee absenteeism: how absenteeism creates costs.

Analytics and Measures for Employee Absenteeism

In the context of absenteeism, analytics refers to formulas (for instance, those for absence rate, total pay, and supervisory time) and to comparisons to industry averages and adjustments for seasonality. Analytics also includes various methodologies used to identify the causes of absenteeism and to estimate variation in absenteeism across different segments of employees or situations. Such methodologies might comprise surveys, interviews with employees and supervisors, and regression analyses.

Measures, on the other hand, focus on specific numbers (for example, finding employee pay and benefit numbers, time sampling to determine the lost time associated with managing absenteeism problems, using the pay and benefits of supervisors as a proxy for the value of their time). Keep these important distinctions in mind as you work through the approach to costing employee absenteeism that is presented next, even though we offer both measures and analytics together here because they are so closely intertwined.

Estimating the Cost of Employee Absenteeism

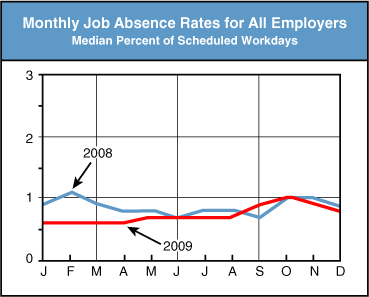

At the outset, it is important to note an important irony: Even in organizations or business units where the concept of absence is relevant, the incidence and, therefore, cost of employee absenteeism is likely to vary considerably across departments or business units. It is considerably higher in organizations or units with low morale, as opposed to those with high morale.11 It also varies across times of the year. With respect to seasonal variations in absenteeism rates, for example, surveys by the Bureau of National Affairs (BNA) in the United States have shown over many years that the incidence of employee absenteeism is generally higher in the winter months than it is in the summer months.12 The costs of absenteeism are therefore likely to covary with seasonal trends, yet it is paradoxical that such costs are typically reported only as averages.

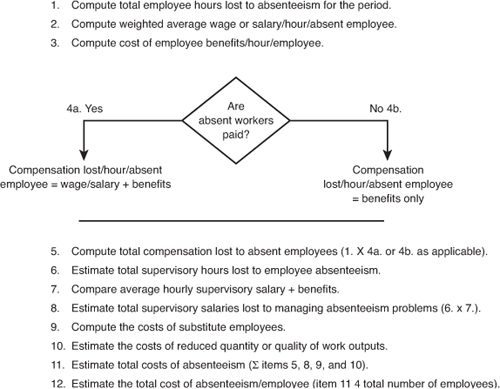

With respect to the cost of employee absenteeism, the following procedure estimates that cost for a one-year period, although the procedure can be used just as easily to estimate these costs over shorter or longer periods as necessary.13

Much of the information required should not be too time-consuming to gather if an organization regularly computes labor-cost data and traditional absence statistics. For example, absenteeism rate is generally based on workdays or work hours, as follows:

Absenteeism rate = [Absence days / Average work force size] × working days, or

Absenteeism rate = [Hours missed / Average work force size] × working hours

In either case, getting the right data involves discussions with both staff and management representatives. Figure 3-3 shows the overall approach.

Figure 3-3. Overall approach to computing employee absenteeism.

To illustrate this approach, we provide examples to accompany each step. The examples use the hypothetical firm Presto Electric, a medium-sized manufacturer of electrical components employing 3,000 people.

Step 1: Total Hours Lost to Absence

Determine the organization’s total employee-hours lost to absenteeism for the period for all employees—blue collar, clerical, and management and professional—for whom the concept of absenteeism is relevant and for those whose jobs are pivotal to the overall success of the organization. Include both whole-day and part-day absences, and time lost for all reasons except organizationally sanctioned time off, such as vacations, holidays, or official “bad weather” days. For example, absences for the following reasons should be included: illness, accidents, funerals, emergencies, and doctor appointments (whether excused or unexcused).

As a basis for comparisons, Figure 3-4 illustrates monthly job absence rates as reported by the BNA. Note the higher absence rates in the fourth quarter, as opposed to the previous three, at least for 2009. Keep in mind also that these data reflect absence patterns during the Great Recession and may not be typical of other time periods.

Figure 3-4. Typical monthly job absence rates.

In our example, assume that Presto Electric’s employee records show 88,200 total employee-hours lost to absenteeism for all reasons except vacations and holidays during the last year. This figure represents an absence rate of 1.5 percent of scheduled work time, about average in nonrecessionary times. Begin by distinguishing hours scheduled from hours paid. Most firms pay for 2,080 hours per year per employee (40 hours per week × 52 weeks). However, employees generally receive paid vacations and holidays, too, time for which they are not scheduled to be at work. If we assume two weeks vacation time per employee (40 hours × 2), plus 5 holidays (40 hours), annual hours of scheduled work time per employee are 2,080 – 80 – 40 = 1,960.

The total scheduled work time for Presto Electric’s 3,000 employees is therefore 3,000 × 1,960 = 5,880,000. Given a 1.5 percent rate of annual absenteeism, total scheduled work hours lost annually to employee absenteeism are 88,200.

Step 2: Compensation for Absent Employees’ Time

If your organization uses computerized absence reporting, then simply compute the average hourly wage/salary paid to absent employees. If not, compute the weighted average hourly wage/salary for the various occupational groups that claimed absenteeism during the period. If absent workers are not paid, skip this step and go directly to step 3.

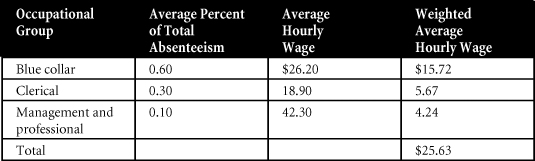

For Presto Electric, assume that about 60 percent of all absentees are blue collar, 30 percent are clerical, and 10 percent are management and professional. For purposes of illustration, we will also assume that all employees are paid for sick days taken under the organization’s employee-benefits program. Estimate the average hourly wage rate per absentee by applying the appropriate percentages to the average hourly wage rate for each major occupational group. Table 3-1 does just that.

Table 3-1. Determining the Average Hourly Wage Rate per Absentee

Step 3: Benefits for Absent Employees’ Time

Estimate the cost of employee benefits per hour per employee. The cost of employee benefits (profit sharing, pensions, health and life insurance, paid vacations and holidays, and so on) currently accounts for about 39 percent of total compensation.14 One procedure for computing the cost of employee benefits per hour per employee is to divide the total cost of benefits per employee per week by the number of hours worked per week.

First, compute Presto’s weekly cost of benefits per employee. Assume that the average annual salary per employee is $25.63 per hour × 2,080 (hours paid for per year), or $53,310.40. Let us further assume the following:

Average annual salary × 39 percent = Average cost of benefits per employee per year

$53,310.40 × 0.39 = $20,791.06

Average cost of benefits per year per employee / 52 weeks per year = Average weekly cost of benefits per employee

$20,791.06 / 52 = $399.83

Average weekly cost of benefits per employee / hours worked per week = Cost of benefits per hour per employee

$399.83 / 40 = $10.00 (rounded)

Step 4: Total Compensation for Absent Employees’ Time

Compute the total compensation lost per hour per absent employee. This figure is determined simply by adding the weighted average hourly wage / salary per employee (item 2 in Figure 3-3) to the cost of employee benefits per hour per employee (item 3 in Figure 3-3). Thus:

$25.63 + $10.00 = $35.63

Of course, if absent workers are not paid, item 4 in Figure 3-3 is the same as item 3.

Step 5: Total Compensation Cost for All Absent Employees

Compute the total compensation lost to absent employees. Total compensation lost, aggregated over all employee-hours lost, is determined simply by multiplying item 1 by item 4.a or 4.b, whichever is applicable. In our example:

88,200 × $35.63 = $3,142,566.00

Step 6: Supervisory Time Spent on Absence Management

Estimate the total number of supervisory hours lost to employee absenteeism for the period. Survey data indicates that supervisors who deal with absenteeism problems spend an average of 3.4 hours a week managing absences.15 That is approximately 41 minutes per day (3.4 / 5 days per week = 0.68 hours per day; 0.68 × 60 minutes = 40.8 minutes per day). Management issues include addressing production problems, locating and instructing replacement employees, checking on the performance of replacements, and counseling and disciplining absentees.

Organizations that want to develop their own in-house estimates might begin by interviewing a representative sample of supervisors using a semi-structured interview format to help them refine their estimates. Areas to probe include the effects of typically high-absence days (Mondays, Fridays, days before and after holidays, days after payday). Although interviews are quite common, diary keeping may actually be more effective. Time sampling for diary-keeping purposes is particularly important, for, as we noted earlier, absenteeism may vary over time. These are by no means the only methods available, and others might also prove useful. Keep in mind that it is true of estimates in general that the more experience companies accumulate in making the estimates, the more accurate the estimates become.16

Methodologically, it is difficult to develop an accurate estimate of the amount of time per day that supervisors spend, on average, dealing with problems of absenteeism. That time is most likely not constant from day to day or from one month to the next. In fact, the time per day, on average, that supervisors spend managing absenteeism problems is likely to vary considerably across departments or business units. Careful consideration of these issues when costing employee absenteeism will yield measurably more accurate results.

After you have estimated the average number of supervisory hours spent per day dealing with employee absenteeism problems, compute the total number of supervisory hours lost to the organization by multiplying three figures:

- Estimated average number of hours lost per supervisor per day

- Total number of supervisors who deal with problems of absenteeism

- The number of working days for the period (including all shifts and weekend work)

In our example, assume that Presto Electric’s data in these three areas is as follows:

- Estimated number of supervisory hours lost per day: 0.68 hours

- Total number of supervisors who deal with absence problems: 100

- Total number of working days for the year: 245

Based on these data, the total number of supervisory hours lost to employee absenteeism is as follows:

0.68 × 100 × 245 = 16,660

Step 7: Pay Level for Supervisors

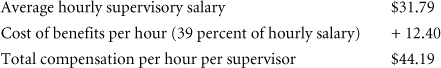

Compute the average hourly wage rate for supervisors, including benefits. Be sure to include only the salaries of supervisors who normally deal with problems of employee absenteeism. Typically, first-line supervisors in the production and clerical areas bear the brunt of absenteeism problems. Estimate Presto Electric’s cost for this figure as follows:

Step 8: Total Supervisor Paid Time Spent on Absence

Compute total supervisory salaries lost to problems of managing absenteeism. This figure is derived simply by multiplying total supervisory hours lost on employee absenteeism (step 6) by the average hourly supervisory wage (step 7), as follows:

16,660 × 44.19 = $736,205.40

Step 9: Costs of Substitute Employees

If an organization chooses to replace workers who are absent, the key considerations are how many substitute employees it will hire and at what cost. Sometimes the total cost is a combination of these two elements, as when some additional workers are hired to replace absentees (say, from an agency that supplies temporary workers) and other, regular workers are asked to work overtime to fill in for the absentees. Alternatively, a very large organization, such as an automobile-assembly plant, might actually retain a regular labor pool that it can draw on to fill in for absent workers. At Presto Electric, let’s assume that the firm incurs total costs of $385,000 per year for substitute employees.

Step 10: Costs of Reduced Quantity or Quality of Work Outputs

When fully productive, regularly scheduled employees are absent, chances are good either that their work is not done or, if it is, that there is a reduction in the quantity or quality of the work. The key considerations in this case are how much of a reduction there is in the quantity or quality of work and how much it costs. In terms of a reduction in productivity, survey data indicate that replacement workers are less productive and require the equivalent of 1.25 people to achieve the same amount of work as the absent employee.17

With respect to costs, they might include items such as the following:

• Machine downtime

• Increases in defects, scrap, and reworks

• Production losses

Consider an example. Suppose a small organization that is operating at full capacity has 100 salespeople in the field calling on accounts and soliciting orders every day. If the typical salesperson generates, on average, $1,000 worth of orders per day, and 10 salespeople are absent on a given day, the business lost to the organization (revenue foregone) due to employee absenteeism on that single day is $10,000.

The standard level of quality or quantity of work might also be compromised through the reduced productivity and performance of less experienced replacement workers, as when customers are served poorly by employees who are stretched trying to “cover” for their absent coworkers, and potential new business is lost as a result of operating “under capacity.”18

As in step 6, some of these estimates will be difficult because many of the components are not reported routinely in accounting or HR information systems. Initially, therefore, determination of the cost elements to be included in this category, plus estimates of their magnitude, should be based on discussions with a number of supervisors and managers. Over time, as the organization accumulates experience in costing absenteeism, it can make a more precise identification and computation of the costs to be included in this category. At Presto Electric, assume that productivity losses and inefficient materials usage as a result of absenteeism caused an estimated financial loss of $400,000 for the year.

Step 11: Total Absenteeism Costs

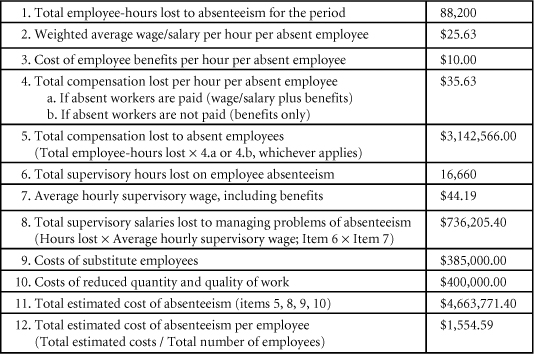

Compute the total estimated cost of employee absenteeism. Having computed or estimated all the necessary cost items, we now can determine the total annual cost of employee absenteeism to Presto Electric. Just add the individual costs pertaining to wages and salaries, benefits, supervisory salaries, substitute employees, and the costs of reduced quantity and quality (items 5, 8, 9, and 10). As Table 3-2 demonstrates, this cost is more than $4.5 million per year.

Table 3-2. Total Estimated Cost of Employee Absenteeism (Presto Electric)

Step 12: Total Costs per Employee per Year

Compute the total estimated cost of absenteeism per employee per year. In some cases, this figure (derived by dividing the total estimated cost by the total number of employees) may be more meaningful than the total cost estimate because it is easier to grasp. In the case of our hypothetical firm, Presto Electric, this figure was $1,554.59 per year for each of the 3,000 employees on the payroll.

Process: Interpreting Absenteeism Costs

As noted in Chapter 2, the purpose of the process component of the logic, analytics, measurements, and process (LAMP) model is to make the insights gained as a result of costing employee absenteeism actionable. The first step in doing that is to interpret absenteeism costs in a meaningful manner. To do so, begin by evaluating them—at least initially—against some predetermined cost standard or financial measure of performance, such as an industry-wide average. This is basically the same rationale organizations use when conducting pay surveys to determine whether their salaries and benefits are competitive.

While the Bureau of National Affairs and the U. S. Bureau of Labor Statistics publish absence rates and lost worktime rates (hours absent as a percent of hours worked) by industry, information on the cost of absenteeism is not published as regularly as are pay surveys. Very little information is available to help determine whether the economic cost of employee absenteeism is a significant problem. The costs of absenteeism to individual organizations occasionally do appear in the literature, but these estimates are typically case studies of individual firms or survey data from a broad cross-section of firms and industries rather than survey data from specific industries.

Is it worth the effort to analyze the costs of absenteeism to the overall organization and, more specifically, to strategically critical business units or departments where the concept of absenteeism is relevant? The answer is yes, for at least two compelling reasons. First, such an analysis calls management’s attention to the severity of the problem. Translating behavior into economic terms enables managers to grasp the burdens employee absenteeism imposes, particularly in strategically critical business units that are suffering from severe absence problems. A six- or seven-figure cost is often the spark needed for management to make a concerted effort to combat the problem. Second, an analysis of the problem creates a baseline for evaluating the effectiveness of absence-control programs. Comparing the quarterly, semiannual, and annual costs of absenteeism across strategically critical business units or departments provides a measure of the success, or lack of success, of attempts to reduce the problem.

If we return to the logical elements of absence cost, we can consider the process you can use to relate those costs to ongoing budget and strategy issues in an organization:

• Cost of payments for nonwork time of absentees: At the outset, recognize that all lost time is connected. This includes absences due to injuries, accidents, short-term disabilities, and absences that are just a few days in duration. To connect absence to tangible process issues for business leaders, look for evidence that levels of paid time off are higher than standard, or benchmarks. Managers and other leaders often signal their interest in reducing the costs paid for nonwork time by noting that sick leave or unscheduled vacation days are higher than they expect. This is an opportunity to take the logic noted earlier and suggest how much sick leave or unscheduled vacation days might change if absence changed.

• Cost of payments for time of those who manage absence: The process signals here will be when supervisors note that they are spending a great deal of time on “nonproductive workforce-management” issues. Are statements like these common when supervisors are setting goals with their managers or during their own performance reviews? Do supervisors and managers often suggest that they could be more effective if they spent less time managing around absent employees? What would they be doing if they did not have to manage employee absence? Answers to these questions allow you to connect absence reductions to tangible changes in supervisor behavior.

• Cost of time of replacement workers: Signals that this is an important cost element emerge when business units see their total labor costs or headcount levels higher than other similar units or benchmarks. Leaders may complain that they often don’t have enough work for all of their employees, but that they must keep the extra employees around to fill in. From a process standpoint, you can use the logic we have described to engage in a discussion about just how much pay for lost time would be reduced if some of the extra employees could be deployed elsewhere or even removed from the workforce.

• Cost of reduced work quantity or quality: The signals here will likely not be found in headcount numbers or labor-cost numbers. Instead, the process for unearthing this evidence will require looking at the performance numbers for operations themselves. Managers and executives might note very specific connections between the fact that when a particular worker fails to be at work, specific things don’t get done, customers don’t get served, or teams have to operate with less than full contributions. When exempt employees have unplanned absences, the 2008 Mercer study on the costs of absenteeism revealed that they make up just 44 percent of their work.19 You can consider these examples and use the logic presented earlier to determine how much of the problem is due to absence and how much investing in absence reduction might change them.

In the next section, we present a case study that moves beyond the calculation of absenteeism costs to illustrate how awareness of those costs led a health-care clinic to address a critical operations issue.

Case Study: From High Absenteeism Costs to an Actionable Strategy

A large, multispecialty health-care clinic was experiencing high absence rates among employees with direct patient-care responsibilities. In terms of costs, the absenteeism problem was impacting the satisfaction of patients with the care they received (and influencing their perceptions of quality). No wonder: Fully 25 percent of patient-care work went undone, and 67 percent of non-patient-care work went undone. Remaining workers suffered from burnout and strained relationships with their supervisors. Of course, employee absenteeism was only one of several possible causes of these problems. Focusing only on reducing absenteeism, per se, might not address important, underlying employee-relations issues.

With the help of a consultant, the clinic sought to identify the root causes of employee absenteeism for the segment of the workforce that had direct patient-care responsibilities. It found that a majority of the absentees were parents who had young children. In many cases, those parents were unable to find emergency or sick-child care, and this caused last-minute staffing shortages due to unscheduled absences. Moreover, the Family Medical and Leave Act permits employees to use their own sick time to care for ill children (and requires employers to grant employees up to 12 weeks of unpaid annual leave).20

Based on this information, management of the clinic made the decision to provide sick-child care and backup child-care facilities both for patients when using the clinic and for employees to use in emergencies. Doing so yielded payoffs in attraction and in retention of members of this critical segment of the clinic’s workforce. One year later, the unscheduled absence rate for employees using the backup child-care facility was 70 percent less than that of employees who were eligible but did not use the facility.21

This finding was certainly good news in terms of the overall employee absence rate, but it suggests the need for further diagnostic information to uncover reasons why employees who were eligible to use the sick-child and backup child-care facilities chose not to do so. That is the nature of HR research: Addressing one problem (in this case, excessive employee absenteeism) helps to identify additional ones that require management attention.

Other Ways to Reduce Absence

In the final part of this chapter, we present two other approaches to managing absenteeism and sick-leave abuse that may prove useful, depending on the diagnosis of root causes. These include positive incentives and paid time-off policies. We hasten to add, however, that organization-wide absenteeism-control methods (for example, rewards for good attendance, progressive discipline for absenteeism, daily attendance records) may be somewhat successful, but they might not be effective in dealing with specific individuals or work groups that have excessively high absenteeism rates. Special methods (such as flexible work schedules, job redesign, and improved safety measures) may be necessary for them. Careful analysis of detailed absenteeism-research data can facilitate the identification of these problems and suggest possible remedies.22

Controlling Absenteeism Through Positive Incentives

This approach focuses exclusively on rewards—that is, it provides incentives for employees to come to work. This “positive-incentive absence-control program” was evaluated over a five-year period: one year before and one year after a three-year incentive program.23

A 3,000-employee nonprofit hospital provided the setting for the study. The experimental group contained 164 employees who received the positive-incentive program, and the control group contained 136 employees who did not receive the program. According to the terms of the hospital’s sick leave program, employees could take up to 96 hours—12 days per year—with pay. Under the positive-incentive program, employees could convert up to 24 hours of unused sick leave into additional pay or vacation. To determine the amount of incentive, the number of hours absent was subtracted from 24. For example, 24 minus 8 hours absent equals 16 hours of additional pay or vacation. The hospital informed eligible employees both verbally and in writing.

During the year before the installation of the positive-incentive program, absence levels for the experimental and control groups did not differ significantly. During the three years in which the program was operative, the experimental group consistently was absent less frequently, and this difference persisted during the year following the termination of the incentives. The following variables were not related to absence: age, marital status, education, job grade, tenure, and number of hours absent two or three years previously. Two variables were related to absence, although not as strongly as the incentive program itself: gender (women were absent more than men, a trend that appears even in the most recent data on absenteeism by gender24) and number of hours absent during the previous year.

Had the incentive program been expanded to include all 3,000 hospital employees, net savings were estimated at $112,000 (in 2010 dollars). This is an underestimate, however, because indirect costs were not included. Indirect costs include such things as the following:

• Increased supervisory time for managing absenteeism problems

• Costs of replacement workers

• Intentional overstaffing to compensate for anticipated absences

Cautions: A positive-incentive program may have no effect on employees who view sick leave as an earned “right” that should be used whether one is sick or not. Moreover, encouraging attendance when a person has a legitimate reason for being absent—for example, hospital employees with contagious illnesses—may be dysfunctional.

In and of itself, absence may simply represent one of many possible symptoms of job dissatisfaction. Attendance incentives may result in “symptom substitution,” whereby declining absence is accompanied by increased tardiness and idling, decreased productivity, and even turnover. If this is the case, an organization needs to consider more comprehensive interventions that are based, for example, on the results of multiple research methods such as employee focus groups, targeted attitude surveys, and thorough analysis and discussion of the implications of the findings from these methods.

Despite the potential limitations, the study warranted the following conclusions (all monetary figures are expressed in 2010 dollars):

• Absenteeism declined an average of 11.5 hours per employee (32 percent) during the incentive period.

• Net costs to the organization (direct costs only) are based on wage costs of $29.35 per hour (composed of $22.58 in direct wages plus 30 percent more in benefits).

• Savings were $55,362 per year (11.5 hours × Average hourly wage [$29.35] × 164 employees).

• Direct costs to the hospital included 2,194 bonus hours, at an average hourly wage of $22.58 per hour = $49,540.

• Net savings were therefore $5,822 per year, for an 11.75 percent return on investment ($5,822 / $49,540).

Paid Time Off (PTO)

This approach to controlling absenteeism and the abuse of sick leave is based on the concept of consolidated annual leave. Sick days, vacation time, and holidays are consolidated into one “bank” to be drawn out at the employee’s discretion. The number of paid time off (PTO) days that employees receive varies across employers. For example, at Pinnacol Assurance, employees receive 20 days of PTO at the start of employment, 25 after five years, and 30 after nine years.25

Employees manage their own sick and vacation time and are free to take a day off without having to offer an explanation. If an employee uses up all of this time before the end of the year and needs a day off, that time is unpaid. What about unused sick time? “Buy-back programs” allow employees to convert unused time to vacation or to accrue time and be paid for a portion of it.

Employers that have instituted this kind of policy feel that it is a “win-win” situation for employees and managers. It eliminates the need for employees to lie (that is, abuse sick leave), and it takes managers out of the role of enforcers. Employees typically view sick leave days as a right—that is, “use them or lose them.” PTO policies provide an incentive to employees not to take off unnecessary time, because excessive absence is still cause for dismissal. PTO is certainly a popular benefit. According to the Society for Human Resource Management’s 2009 employee benefits report, 42 percent of respondents said their employers had such a plan. Employers rate them as the most effective of all absence-control programs.26

Summary Comments on Absence-Control Policies

A comprehensive review of research findings in this area revealed that absence-control systems can neutralize some forms of absence behavior and catalyze others.27 Although the positive-incentive program described earlier was effective in reducing absenteeism over a three-year period, one study showed that absence-control policies could actually encourage absence.28 In the firm studied, employees had to accumulate 90 days of unused sick leave before they could take advantage of paid sick leave (for one- to two-day absences). The policy suppressed absences only until employees reached the paid threshold, at which time they took sick leave ferociously.

Other studies have shown that punishments, or stricter enforcement of penalties for one type of absence, tend to instigate other forms of missing work.29 This is not to suggest, however, that absence-control policies should be lenient. Unionized settings, where sick-leave policies are typically more generous, are clearly prone to higher absenteeism.30 Such policies convey a relaxed norm about absenteeism, and research evidence clearly indicates that those norms can promote absence taking.31

Applying the Tools to Low Productivity Due to Illness: “Presenteeism”

Slack productivity from ailing workers is sometimes called presenteeism.32 Like absenteeism, presenteeism is a form of withdrawal behavior. It often results from employees showing up but working at subpar levels due to chronic ailments,33 and it is more sensitive to working-time arrangements than absenteeism is. Permanent full-time work, mismatches between desired and actual working hours, shift work, and overlong working weeks increase presenteeism, holding other worker characteristics constant.34 Major reasons for presenteeism include a sense of obligation to coworkers, too much work, and impending deadlines.35

This is not a new category of costs, but rather an illustration of our fourth cost category: the costs of reduced quantity or quality of work. In a recent study, for example, researchers analyzed more than 1.1 million medical and pharmacy claims along with detailed responses from the Health and Work Performance Questionnaire in a multiyear study. It included ten corporations that employed more than 150,000 workers.36 The study found that, on average, every $1 of medical and pharmacy costs is matched to $2.30 of health-related productivity costs—and that figure is much greater for some conditions. When health-related productivity costs are measured along with medical and pharmacy costs, the top chronic health conditions driving these overall health costs are depression, obesity, arthritis, back or neck pain, and anxiety.

Surprisingly, presenteeism may actually be a much costlier problem than its productivity-reducing counterpart, absenteeism. Unlike absenteeism, however, presenteeism isn’t always apparent. Absenteeism is obvious when someone does not show up for work, but presenteeism is far less obvious when illness or a medical condition is hindering someone’s work. Researchers are just beginning to address presenteeism and to estimate its economic effects.

• Logic: Research on presenteeism focuses on chronic or episodic ailments such as seasonal allergies, asthma, migraines, back pain, arthritis, gastrointestinal disorders, and depression.37 Progressive diseases, such as heart disease and cancer, tend to occur later and life and generate the majority of direct health-related costs for companies. In contrast, the illnesses people take with them to work account for far lower direct costs, but they imply a greater loss in productivity because they are so prevalent, so often go untreated, and typically occur during peak working years. Those indirect costs have largely been invisible to employers.38

• Analytics: To be sure, methodological problems plague current research in this area. Different research methods have yielded quite different estimates of the on-the-job productivity loss—from less than 20 percent of a company’s total health-related costs to more than 60 percent.39 Beyond that, how does one quantify the relative effects of individual ailments on productivity for workers who suffer from more than one problem? The effects of such interactions have not been addressed. Nor has the effect on team performance been studied in cases when one member has a chronic health condition that precludes him or her from contributing fully to the team’s mission.

• Measures: A key question to address is the link between self-reported presenteeism and actual productivity loss. Some of the strongest evidence of such a link comes from several studies involving credit card call center employees at Bank One, which is now part of J. P. Morgan Chase.40

There are a number of objective measures of a service representative’s productivity, including the amount of time spent on each call, the amount of time between calls (when the employee is doing paperwork), and the amount of time the person is logged off the system. The study focused on employees with known illnesses (identified from earlier disability claims) and lower productivity scores. One such study, a good example of analytics in action, involved 630 service representatives at a Bank One call center in Illinois. Allergy-related presenteeism was measured with such objective data as the amount of time workers spent on each call. During the peak ragweed pollen season, the allergy sufferers’ productivity fell 7 percent below that of coworkers without allergies. Outside of allergy season, the productivity of the two groups was approximately equal.

• Process: The next step, of course, is to use this information to work with decision makers to identify where investments to reduce the costs of presenteeism offer the greatest opportunities to advance organizational objectives. One way to improve productivity is by educating workers about the nature of the conditions that afflict them and about appropriate medications to treat those conditions. Companies such as Comerica Bank, Dow Chemical, and J. P. Morgan Chase are among those that have put programs in place to help employees avoid or treat some seemingly smaller health conditions, or at least to keep productive in spite of them.41 To ensure employee privacy, for example, Comerica Bank used a third party to survey its employees and found that about 40 percent of them suffered from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which can involve abdominal discomfort, bloating, or diarrhea. Extrapolating from that, the company estimated its annual cost of lost productivity to be at least $9 million a year (in 2010 dollars). Comerica now provides written materials for its employees about IBS and has sponsored physician seminars to educate workers on how to recognize and deal with it through their living habits, diet, and possible medications.

Education is one thing, but getting workers to take the drugs that their doctors prescribe or recommend is another. The Bank One study found that nearly one quarter of allergy sufferers did not take any kind of allergy medication. The same study also concluded that covering the cost of nonsedating antihistamines for allergy sufferers (roughly $21 a week for prescription medications, less for generics) was more than offset by the resulting gains in productivity (roughly $42 a week, based on call center employees’ wages and benefits, which averaged $603 a week in 2010 dollars).42

These results raise a tantalizing question: Might a company’s pharmacy costs actually be an investment in workforce productivity? Certainly, companies should monitor and control corporate health-care expenditures. It is possible, however, that by increasing company payments for medications to treat chronic diseases, companies might actually realize a net gain in workforce productivity and eliminate the opportunity costs of failing to address the presenteeism issue directly. One obvious example of this is the flu shot. Numerous studies have shown that the cost of offering free flu shots is far outweighed by the savings realized through reductions in both absenteeism and presenteeism.43 Another simple approach to reducing presenteeism is to offer paid time off, as discussed earlier. Implementing even a modest program of sick leave may well offset the reduced productivity associated with chronic presenteeism.

Exercises

Software that calculates answers to one or more of the following exercises can be found at http://hrcosting.com/hr/.

- Consolidated Industries, an 1,800-employee firm, is faced with a serious—and growing—absenteeism problem. Last year, total employee-hours lost to absenteeism came to 119,808. Of the total employees absent, 65 percent were blue collar (average wage of $25.15 per hour), 25 percent were clerical (average wage of $19.80 per hour), and the remainder were management and professional (average salary $37.60 per hour). On average, the firm spends 38 percent more of each employee’s salary on benefits and, as company policy, pays workers even if they are absent.

The 45 supervisors (average salary of $29.35 per hour) involved in employee absenteeism problems estimate that they lose 40 minutes per day for each of the 245 days per work year just dealing with the extra problems imposed by those who fail to show up for work. Finally, the company estimates that it loses $729,500 in additional overtime premiums, in extra help that must be hired, and in lost productivity from the more highly skilled absentees. As HR director for Consolidated Industries, your job is to estimate the cost of employee absenteeism so that management can better understand the dimensions of the problem.

- Inter-Capital Limited is a 500-employee firm faced with a 3.7 percent annual absenteeism rate over the 1,960 hours that each employee is scheduled to work. About 15 percent of absentees are blue collar (average wage $26.96 per hour), 55 percent are clerical employees (average wage $20.25 per hour), and the remainder are management and professional workers (average salary $44.50 per hour). About 40 percent more of each employee’s salary is spent on benefits, but employees are not paid if they are absent from work. In the last six months, supervisors (average salary of $29.75 per hour) estimate that managing absenteeism problems costs them about an hour a day for each of the 245 days per work year. It’s a serious problem that must be dealt with, since about 20 supervisors are directly involved with absenteeism. On top of that, the firm spends approximately $590,000 more on costs incidental to absenteeism. Temporary help and lost productivity can really cut into profits. Just how much is absenteeism costing Inter-Capital Limited per year per employee? (Use the software available at http://hrcosting.com/hr/.)

- As a management consultant, you have been retained to develop two alternative programs for reducing employee absenteeism at Consolidated Industries (see question 1). Write a proposal that addresses the issue in specific terms. Exactly what should the firm do? (To do this, make whatever assumptions seem reasonable.)

References

1. Fox, A., “The Ins and Outs of Customer-Contact Centers,” HR Magazine 55 (March 2010): 28–31. See also Fraser-Blunt, M., “Call Centers Come Home,” HR Magazine 52, no. 1 (January 2007): 85–89.

2. Worldatwork, Telework Trendlines 2009 (Scottsdale, Ariz.: Worldatwork, 2009). See also Fox, A., “At Work in 2020,” HR Magazine (January 2010): 18–23.

3. Hausknecht, J. P., N. J. Hiller, and R. J. Vance, “Work-Unit Absenteeism: Effects of Satisfaction, Commitment, Labor-Market Conditions, and Time,” Academy of Management Journal 51 (2008): 1,223–1,245. See also Rentsch, J. R., and R. P. Steel, “Testing the Durability of Job Characteristics as Predictors of Absenteeism over a Six-Year Period,” Personnel Psychology 51 (1998): 165–190.

4. Harrison, D. A., and J. J. Martocchio, “Time for Absenteeism: A 20-Year Review of Origins, Offshoots, and Outcomes,” Journal of Management 24, no. 3 (1998): 305–350. See also Johns, G., “Contemporary Research on Absence from Work: Correlates, Causes, and Consequences,” in International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology 12, ed. C. L. Cooper and L. T. Robertson (New York: Wiley, 1997).

5. “Managing Employee Attendance,” June 15, 2009. Downloaded May 11, 2010 from www.shrm.org/Research/Articles/Articles/Pages/ManagingEmployeeAttendance.aspx. See also Klachefsky, M., “Take Control of Employee Absenteeism and the Associated Costs,” October 9, 2008. Downloaded May 11, 2010 from www.mercer.com.

6. “Sickies and Long-Term Absence Give Employers a Headache—CBI/AXA Survey,” May 14, 2008. Downloaded from www.cbi.org.uk on May 11, 2010.

7. Current Population Survey, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, April 9, 2010. Downloaded from /www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat46.pdf on May 12, 2010.

8. “Sickies and Long-Term Absence,” 2008.

9. “Managing Employee Attendance,” 2009.

10. Warren, J., “Cough If You Need Sick Leave,” Bloomberg Businessweek (June 13, 2010): 33.

11. “Managing Employee Attendance,” 2009.

12. BNA, “Job Absence and Turnover,” 4th Quarter, 2009. Downloaded from www.bna.com/pdf/jat4q09.pdf on May 12, 2010.

13. This method is based upon that described by F. E. Kuzmits in “How Much Is Absenteeism Costing Your Organization?” Personnel Administrator 24 (June 1979): 29–33.

14. Cascio, W. F., Managing Human Resources: Productivity, Quality of Work Life, Profits, 8th ed. (Burr Ridge, IL: Irwin/McGraw-Hill, 2010).

15. Managing employee attendance, 2009.

16. Cascio, W. F., and H. Aguinis, “Applied Psychology in Human Resource Management,” 7th ed. (Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 2011).

17. “Managing employee attendance,” 2009.

18. Cyboran, S. F., “Absence Management: Costs, Causes, and Cures,” workshop presented at Mountain States Employers Council, HR Best Practices Conference, Denver, Col. April 13, 2006.

20. Society for Human Resource Management, FMLA: An Overview of the 2007 FMLA survey (Alexandria, Va.: SHRM, 2007).

22. Miners, I. A., M. L. Moore, J. E. Champoux, and J. J. Martocchio, “Time-Serial Substitution Effects of Absence Control on Employee Time Use,” Human Relations 48, no. 3 (1995): 307–326.

23. Schlotzhauer, D. L., and J. G. Rosse, “A Five-Year Study of a Positive Incentive Absence Control Program,” Personnel Psychology, 38 (1985): 575–585.

24. Current Population Survey, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2010.

25. Frase, M., “Taking Time Off to the Bank,” HR Magazine 55 (March 2010): 41–46.

27. Harrison and Martocchio, 1998.

28. Dalton, D. R., and D. J. Mesch, “On the Extent and Reduction of Avoidable Absenteeism: An Assessment of Absence Policy Provisions,” Journal of Applied Psychology 76 (1991): 810–817.

30. Drago, R., and M. Wooden, “The Determinants of Labor Absence: Economic Factors and Workgroup Norms Across Countries,” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 45 (1992): 764–778.

31. Harrison and Martocchio, 1998.

32. Goetzel, R. Z., S. R. Long, R. J. Ozminkowski, K. Hawkins, S. Wang, and W. Lynch, “Health, Absence, Disability, and Presenteeism Cost Estimates of Certain Physical and Mental Health Conditions Affecting U.S. Employers,” Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 46, no. 4 (2004): 398–412.

33. Rubinstein, S., “Nursing Employees Back to Health,” The Wall Street Journal, 18 January 2005, D5.

34. Böckerman, P., and E. Laukkanen, “What Makes You Work While You Are Sick? Evidence from a Survey of Workers,” European Journal of Public Health 20, no. 1 (2010): 43–46.

35. Gurschiek, K., “Sense of Duty Beckons Sick Employees to Work,” HR News (April 29, 2008). Available at www.shrm.org/Publications/HRNews/Pages/SenseofDutyBeckons.aspx.

36. Loeppke, R., M. Taitel, V. Haufle, T. Parry, R. Kessler, and K. Jinnett, “Health and Productivity as a Business Strategy: A Multiemployer Study,” Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 51, no. 4 (2009): 411–428.

37. Hemp, P. “Presenteeism: At Work—But Out of It,” Harvard Business Review 82 (October 2004): 1–9.