Chapter 4. The High Cost of Employee Separations

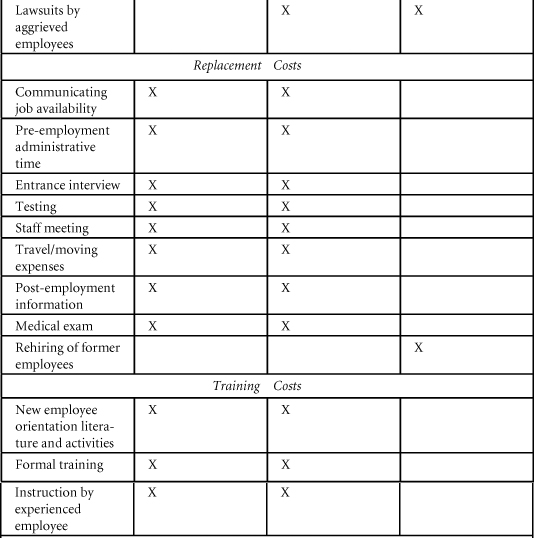

Employee separations (often called turnover) occur when an employee permanently leaves an organization. Google developed a formula that predicts the probability that each employee will leave. The Wall Street Journal reported that Google’s formula helps the company “get inside people’s heads even before they know they might leave,” says Laszlo Bock, who runs human resources for the company.1 If we know someone may leave, should we try to stop him or her? The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reports monthly job opening and labor turnover rates. Figure 4-1 shows the monthly results from years 2000–2010. These monthly rates translate into annual rates that were as high as 31 percent in 2001 and as low as 19 percent in 2009, following the global economic downturn. This figure varies widely by industry, with manufacturing figures ranging from 15 percent in 2001 to only 9 percent in 2009, and accommodations and food services from 63 percent in 2001 to 39 percent in 2009.2

Figure 4-1. U.S. private sector quit rates for years 2000–2009.

To appreciate what that means for an individual firm, consider that, in the fiscal year ending January 2010, Wal-Mart reported employing 2.1 million associates worldwide.3 The average annual quit rate for the retail trade industry in 2009 was 25 percent (down from 40 percent in 2006).4 Each year, therefore, Wal-Mart must recruit, hire, and train about 525,000 new employees just to replace those who left.

Is this level of turnover good or bad for Wal-Mart? It is a safe bet that just processing and managing this level of employee turnover costs millions of dollars per year, but then Wal-Mart’s annual after-tax profits were $14 billion in 2009.5 So the cost of turnover for Wal-Mart is a big number but not a large percentage of its profits. Although Wal-Mart could likely save millions of dollars a year by reducing turnover, what would be the investment necessary to do that? Also, if turnover was reduced by hiring employees who have fewer alternative employment options (and thus are less likely to leave), might that also mean getting employees who are less qualified or who have lower performance? Long-term employees also amass increased obligations in terms of pension and health-care coverage, so it is possible that Wal-Mart saves money in these areas if its workforce has shorter tenure.

On the other hand, perhaps the short tenure of the workforce reduces learning and customer service skills that would enhance Wal-Mart’s performance. These are complex questions that are often overlooked when organizations adopt simple decision rules, such as “reduce all turnover to below the industry average.” In this chapter, we provide frameworks to address such questions, and thus improve the ways organizations manage this important aspect of their talent resource.

The Logic of Employee Turnover: Separations, Acquisitions, Cost, and Inventory

Employee turnover is often measured by how many employees leave an organization. A more precise definition is that turnover includes replacing the departed employee (hence the idea of “turning over” one employee for another). We distinguish employee separations from the employee acquisitions that replace the separated employees. Employee separations and acquisitions are “external movements,” meaning that they involve moving across the organization’s external boundary. (We discuss movements inside the organization later.)

External movements define situations that include pure growth (acquisitions only), pure reduction (separations only), and all combinations of growth and reduction, including steady state, with the number of acquisitions equaling the number of separations.6 Employee turnover (where each separation is replaced by an acquisition) is one common and important combination, but the frameworks discussed here are helpful when managing any combination of external employee movements. We find it also very helpful to distinguish employee separations from employee acquisitions, although the term turnover usually refers to separations that are replaced.

Decisions affecting employee movement reflect three basic parameters:

• The quantity of movers

• The quality of movers (that is, the strategic value of their performance)

• The costs incurred to produce the movement (that is, the costs of acquisitions or separations)

Decisions affecting the acquisition of new employees (that is, selection decisions) require considering the quantity, quality, and cost of those acquisitions. Likewise, decisions affecting the separation of employees (that is, layoffs, retirements, and employee turnover) require considering the quantity, quality, and cost to produce the separations.

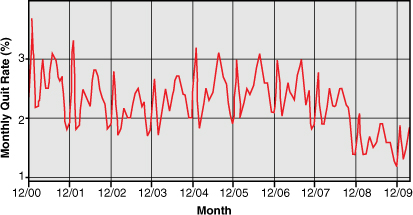

The important points to remember are that the results of decisions that affect acquisitions or separations are expressed through quantity, quality, and cost. Second, the consequences of these decisions often depend on the interaction between the effects of acquisitions and separations. Figure 4-2 shows these ideas graphically.

Figure 4-2. Logic of employee turnover.

In each period, two processes can change workforce value: Employees are added and employees separate. As time goes on, these same two processes continue, with the beginning workforce value in the new time period being the ending workforce value from the last time period. This diagram is useful to reframe how organization leaders approach employee separations, hiring, shortages, and surpluses. The diagram shows that if leaders consider only turnover rates and costs, they are focusing only on the two boxes shown at the bottom of Figure 4-2. When their only consideration is filling requisitions quickly, they are focusing on the quantity of employees added: only the top box.

The figure is intentionally similar to traditional raw materials or unfinished goods inventory diagrams that allow leaders easily to see that their decisions about workforce inventories are at least as important as their decisions about any other kind of inventory. They can also see the dangers of focusing only on one box, and they can see what additional factors they should consider if they want to optimize workforce quality, cost, shortages, and surpluses. This diagram makes it easier for leaders to see how things like turnover, time to fill, and hiring costs are integrated.

The word turnover actually originated with inventory management. In a retail store, inventory “turns over” when it is depleted (sold, stolen, spoiled, and so on) and replaced. The rate of inventory depletion is the turnover rate. Inventory management doesn’t just focus solely on whether depletion rates are at benchmark levels or could be reduced. Indeed, if depletion is due to profitable sales, the organization may actually want to increase it.

Instead, inventory optimization integrates the depletion rate into broader questions concerning the optimum level of inventory, optimum costs of replenishing and depleting inventory, and how frequently shortages and surpluses occur. In the same way, employee turnover is best thought of as part of a system that includes the costs and patterns of employee acquisitions, the value and quality of the workforce, and the costs and investments that affect all of them. Boudreau and Berger developed mathematical formulas to express the overall payoff (utility) or net benefits of workforce acquisitions and separations.7 In Retooling HR, Boudreau shows that the logic of Figure 4-2, combined with the use of inventory-optimization techniques, can retool turnover management beyond turnover reduction, to optimizing employee surpluses and shortages.8 We return to this idea in Chapter 10, “The Payoff from Enhanced Selection.”

This chapter focuses on identifying and quantifying the transaction costs associated with external employee separations and the transaction costs of the acquisitions to replace those who left (including the activities to acquire them and train them).

Two popular ways of classifying employee turnover are voluntary versus involuntary and functional versus dysfunctional. We discuss these distinctions next. Then, consistent with the LAMP framework that we introduced in Chapter 1, “Making HR Measurement Strategic,” we discuss the analytics, measurement, and processes involved in computing, interpreting, and communicating the actual costs of employee turnover.

Voluntary Versus Involuntary Turnover

Turnover may be voluntary on the part of the employee (for example, resignation) or involuntary (for example, requested resignation, permanent layoff, retirement, or death). Voluntary reasons for leaving—such as another job that offers more responsibility, a return to school full time, or improved salary and benefits—are more controllable than involuntary reasons, such as employee death, chronic illness, or spouse transfer. Most organizations focus on the incidence of voluntary employee turnover precisely because it is more controllable than involuntary turnover. They are also interested in calculating the costs of voluntary turnover, because when these costs are known, an organization can begin to focus attention on reducing them, particularly where such costs have significant strategic effects.

Functional Versus Dysfunctional Turnover

A common logical distinction focuses on whether voluntary turnover is functional or dysfunctional for the organization. Employee turnover has been defined as functional if the employee’s departure produces increased value for the organization. It is dysfunctional if the employee’s departure produces reduced value for the organization. Often this is interpreted to mean that high performers who are difficult to replace represent dysfunctional turnovers, and low performers who are easy to replace represent functional turnovers.9 Figure 4-2 provides a more precise definition. Turnover is functional when the resulting difference in workforce value is positive and high enough to offset the costs of transacting the turnover. Turnover is dysfunctional when the resulting difference in workforce value is negative or the positive change in workforce value doesn’t offset the costs. The difficulty of replacement is not inconsistent with this idea, but it is a lot less precise. Does “difficult to replace” mean that replacements will be of lower value than the person who left, or that they will be of higher value but very costly?

Performance, of course, has many aspects associated with it. Some mistakes in selection are unavoidable, and to the extent that employee turnover is concentrated among those whose abilities and temperaments do not fit the organization’s needs, that is functional for the organization and good for the long-term prospects of individuals, too. Other employees may have burned out, reached a plateau of substandard performance, or developed such negative attitudes toward the organization that their continued presence is likely to have harmful effects on the motivation and productivity of their coworkers. Here, again, turnover can be beneficial, assuming, of course, that replacements add more value than those they replaced.

On the flip side, the loss of hard-working, value-adding contributors is usually not good for the organization. Such high performers often have a deep reservoir of firm-specific knowledge and unique and valuable personal characteristics, such as technical and interpersonal skills. It is unlikely that a new employee would have all of these characteristics, and very likely that he or she would take a long time to develop them. Thus, voluntary turnover among these individuals, and the need to replace them with others, is likely to reduce the value of the workforce and produce costs associated with their separation and replacement. Voluntary turnover is even more dysfunctional, however, when it occurs in talent pools that are pivotal to an organization’s strategic success.

Pivotal Talent Pools with High Rates of Voluntary Turnover

Just as companies divide customers into segments, they can divide talent pools into segments that are pivotal versus nonpivotal. Pivotal talent pools are those where a small change makes a big difference to strategy and value. Instead of asking “What talent is important?” the question becomes “Where do changes in the quantity or quality of talent make the biggest difference in strategically important outcomes?” For example, where salespeople have a lot of discretion in their dealings with customers, and those dealings have big effects on sales, the difference in performance between an average and a superior salesperson is large. Replacements also likely will be lower performers because the skills needed to execute sales are learned on the job; as a result, workforce value sees a substantial reduction when a high performer leaves and is replaced by a new recruit.

On the other hand, in some jobs, performance differences are smaller, such as in a retail food service job where there are pictures rather than numbers on the cash register and where meals are generally sold by numbers instead of by individualized orders. Here the value produced by high performers is much more similar to the value of average performers. The job is also designed so that replacement workers can learn it quickly and perform at an acceptable level. So in this job, voluntary turnover among high performers, who are replaced by average performers, does not produce such a large change in workforce value. If the costs of processing departures and acquisitions are low, it may be best not to invest in reducing such turnover.

Even in fast-food retail, deeply understanding the costs and benefits of employee turnover can be enlightening. David Fairhurst, vice president and Chief People Officer for McDonald’s restaurants in Northern Europe, was voted in 2009 the most influential HR practitioner by HR Magazine in the United Kingdom. Fairhurst invited a university study examining the performance of 400 McDonald’s restaurants in the United Kingdom. The study found that customer satisfaction levels were 20 percent higher in outlets that employed kitchen staff and managers over age 60 (the oldest was an 83-year-old woman employed in Southampton).10

Fairhurst later noted that “sixty percent of McDonald’s 75,000-strong workforce are under 21, while just 1,000 are aged over 60 .... Some 140 people are recruited every day but only 1.0 to 1.5 percent of those are over 60.”11 So turnover among the older employees is much more significant than turnover among the younger ones.

We noted earlier that many analysts and companies refine an overall measure of employee turnover by classifying it as controllable or voluntary (employees leave by choice), or uncontrollable or involuntary (for example, retirement, death, dismissal, layoff). After pivotal pools of talent have been identified, it becomes important to measure their voluntary employee-turnover rates, to assess the cost of that voluntary turnover, to understand why employees are leaving, and to take steps to reduce voluntary and controllable turnover. Turnover rates in pivotal talent pools need not be high to be extremely costly. Ameriprise Financial provides its leaders with various “cuts” of turnover data by presenting them with a map that shows where the high performers are least engaged and, thus, most likely to leave.12 Departures of high performers receive more attention than departures of middle or low performers, and those with low engagement get more attention because of their greater likelihood of leaving (see Chapter 6, “Employee Attitudes and Engagement”).

Voluntary Turnover, Involuntary Turnover, For-Cause Dismissals, and Layoffs

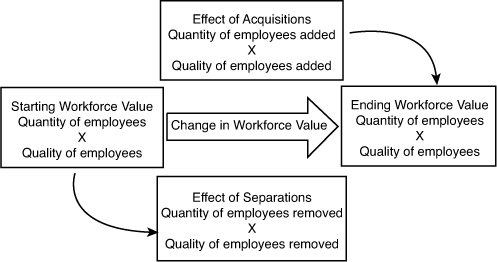

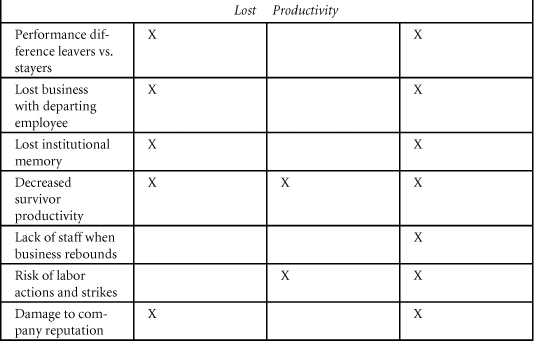

This section shows how to compute the turnover cost elements. However, not all costs apply to all types of turnover. Let’s first review which categories of costs apply to which type of employee separations. Table 4-1 provides a guide.

Table 4-1. How Turnover Cost Elements Apply to Different Types of Turnover

In the sections that follow, we focus mostly on the costs associated with voluntary quits and for-cause dismissals. Such separations are by far the more prevalent in most companies. Moreover, most of the costs of layoffs are also associated with the other two types of turnover, so the analytic approaches described next can also be used for layoffs.

However, it is worth noting that the costs of layoffs are often much higher than most organizations realize, and some costs are unique to the layoff situation. In Employment Downsizing and Its Alternatives, Cascio notes that direct costs may be as much as $100,000 per layoff, and that, in 2008, IBM spent $700 million on employee restructuring.13 Short-term or one-time costs of layoffs include most costs, and in the long run the costs of layoffs can include the rehiring of former employees, pension and severance payouts, and indirect costs of lost productivity. Longer-term concerns include additional lost time of survivors, who worry about losing their jobs, potential backlash from clients or customers if the layoffs are perceived as unfair, and increased voluntary separations.

How to Compute Turnover Rates

Conceptually, annual employee turnover is computed by adding up the monthly turnover for a 12-month period. Monthly turnover is calculated as the number of employee separations during the month divided by the average number of active employees during the same month. More generally, the rate of turnover in percent over any period can be calculated by the following formula:

![]()

In the United States, as shown in Figure 4-1, aggregate monthly turnover rates averaged about 1.5 percent, or 18 percent per year. The turnover rate in any given year can be misleading, however, because turnover rates are inversely related to unemployment rates (local, regional, and national). As Figure 4-1 shows, turnover rates were 1.5 to 2 times higher before 2008, when unemployment rates were lower, than after the 2009 economic downturn, when unemployment was higher. One study reported a correlation of –0.84 between unemployment and voluntary employee turnover in the years between 1945 and 1976.14

Typically, organizations compute turnover rates by business unit, division, diversity category, or tenure with the company. Then they attempt to benchmark those turnover rates against the rates of other organizations to gauge whether their rates are higher, lower, or roughly the same as those of competitors or their own industries. Many HR information systems allow managers to “drill down” on turnover rates in a vast number of ways. Indeed, probably hundreds of different turnover rates can be calculated, tracked, and put into various scorecards.

Logical Costs to Include When Considering Turnover Implications

Turnover can represent a substantial cost of doing business. Indeed, the fully loaded cost of turnover—not just separation and replacement costs, but also the exiting employee’s lost leads and contacts, the new employee’s depressed productivity while he or she is learning, and the time coworkers spend guiding the new employee—can easily cost 150 percent or more of the departing person’s salary.15 Pharmaceutical giant Merck & Company found that, depending on the job, turnover costs 1.5 to 2.5 times annual salary.16 At Ernst & Young, the cost to fill a position vacated by a young auditor averaged 150 percent of the departing employee’s annual salary.17 These results compare quite closely to those reported in the Journal of Accountancy—namely, that the cost of turnover per person ranges from 93 percent to 200 percent of an exiting employee’s salary, depending on the employee’s skill and level of responsibility.18

Unfortunately, many organizations are unaware of the actual cost of turnover. Unless this cost is known, management may be unaware of the financial implications of turnover rates, especially among pivotal talent pools. Management also may be unaware of the need for action to prevent controllable turnover and may not develop a basis for choosing among alternative programs designed to reduce turnover.

Organizations need a practical procedure for measuring and analyzing the costs of employee turnover, because the costs of hiring, training, and developing employees are investments that must be evaluated just like other corporate resources. The objective in costing human resources is not only to measure the relevant costs, but also to develop methods and programs to reduce the more controllable aspects of these costs. Analytics and measurement strategies can work together to address these important issues.

Analytics

Analytics focuses on creating a design and analyses that will answer the relevant questions. Although computing turnover rates for various subcategories of employees or business units is instructive, our main focus in this chapter is on the financial implications associated with turnover. We use the term analytics to refer to formulas (for example, for turnover rates and costs), as well as the research designs and analyses that analyze the results of those formulas. Turnover measures are the techniques for actually gathering information—that is, for populating the formulas with relevant numbers. In the following sections, therefore, we describe how to identify and then measure turnover costs. You will see both formulas and examples that include numbers in those formulas. As you work through this information, keep in mind the distinction between analytics and measures.

The general procedure for identifying and measuring turnover costs is founded on three major separate cost categories: separation costs, replacement costs, and training costs.19 In addition, it considers the difference in dollar-valued performance between leavers and their replacements. Finally, the fully loaded cost of turnover should include the economic value of lost business, if possible.20 Notice how these elements precisely mirror the categories in Figure 4-2. There are costs of the transactions required to complete the separation of the former employee, and also of acquiring and training the replacement. The difference in performance between stayers and leavers is part of the change in workforce value, as is the business that is lost with the leaver.

For each of these categories, we first present the relevant cost elements and formulas (analytics); then we provide numeric examples to illustrate how the formulas are used (measures). The “pay rates” referred to in each category of costs refer to “fully loaded” compensation costs (that is, direct pay plus the cost of benefits).

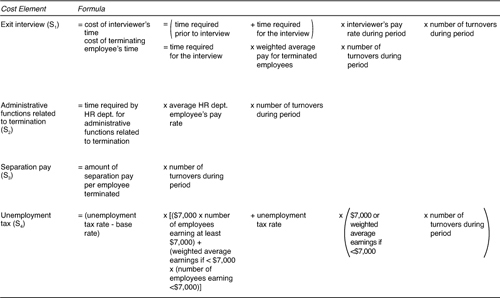

Separation Costs

Figure 4-3 presents the key cost elements, together with appropriate formulas for each, that apply to separation costs. These include exit interviews (S1); administrative functions related to termination, such as deletion of the exiting employee from payroll, employment, and benefits files (S2); separation pay, if any (S3); and unemployment tax, if applicable (S4).

Figure 4-3. Measuring separation costs.

Thus:

Total separation costs (ST) = S1 + S2 + S3 + S4

The cost of exit interviews is composed of two factors, the cost of the interviewer’s time (preparation plus actual interview time) and the cost of the terminating employee’s time (time required for the interview × weighted average pay rate for all terminated employees). This latter figure may be calculated as follows:

Times for exit interviews may be estimated in one of two ways:

• Time a random sample of exit interviews and calculate the average time.

• Interview a representative sample of managers who conduct exit interviews regularly and average their estimated times.

Each organization should specify exactly what administrative functions relate to terminations and the time required for them. Each of those activities costs money, and the costs should be documented and included when measuring separation costs.

Separation pay, for those organizations that offer it, can usually be determined from the existing accounting information system. Length of service, organization level, and the cause of termination are key factors that affect the amount of severance pay. Termination for poor performance generally does not include a severance package. Most lower-level employees receive one or two weeks of pay for each year they worked, up to a maximum of about 12 weeks. Midlevel managers typically receive anywhere from three to six months of pay; higher-level executives, six months to one year of pay; and chief executive officers with employment contracts two to three years of salary.21 Fully 88 percent of organizations now require a signed release in exchange for payment, whether in a lump sum or through salary continuation. Medical benefits typically continue throughout the severance period.

Among organizations that do business in the United States, unemployment tax is relevant. For those doing business elsewhere, this item should not be included in separation costs. United States employers’ unemployment tax rates include federal and state taxes, of which the federal tax equals 6.2 percent of the first $7,000 of each employee’s earnings, and states impose a tax above that figure.22 For example, in Colorado, the 2010 state tax is 2.48 percent of the first $10,000 in wages.23 Due to rising jobless claims during the great recession, at least 35 states hiked their tax rates or wages subject to unemployment taxes in 2010.24 Employers’ actual tax rates are based on their history of claims. Those with fewer claims for unemployment benefits are subject to a lower unemployment tax than those with more unemployment claims. This increase in unemployment tax due to an increased incidence of claims is an element of separation costs.

In practice, high turnover rates that lead to high claims for unemployment compensation by former employees increase the cost of unemployment tax in two ways. First, the state increases the employer’s tax rate (called the “penalty” in this instance). Second, the employer must pay additional, regular unemployment tax because of the turnovers. For example, consider a 100-employee firm with a 20 percent annual turnover rate (that is, 20 people) and a history of relatively few claims. The total increase in unemployment tax is computed as follows:

(New tax rate minus base rate) × [$10,000 × (100 + 20)]

= (5.4% – 5.0%) × [$1,200,000] = $4,800

Additional unemployment tax due to turnover:

(New tax rate) × ($10,000 × Number of turnovers during period)

= (5.4%) × ($10,000 x 20) = $10,800

Total additional unemployment tax due to turnover:

$4,800 + $10,800 = $15,600

What about the incremental costs associated with taxes to fund public retirement programs (such as the Social Security program in the U.S.)? These costs should be included only if the earnings of those who leave exceed the taxable wage base for the year. Thus, in the U.S. in 2010, the taxable wage base was $106,800, and the employer’s share of those taxes was 7.65 percent. If an employee earning $80,000 per year leaves after six months, for example, the employer pays tax on only $40,000. If it takes one month to replace the departing employee, the replacement earns five months’ wages, or $33,333. Thus, the employer incurs no additional social security tax because the total paid for the position for the year is less than $106,800. However, if the employee who left after six months was a senior manager earning $250,000 per year, the employer would already have paid the maximum tax due for the year for that employee. If a replacement works five months (earning $104,167), the employer then incurs additional social security tax for the replacement.

A final element of separation costs that should be included, if possible, is the cost of decreased productivity due to employee terminations. This may include the decline in the productivity of an employee prior to termination or the decrease in productivity of a the work group that lost the employee. The evidence regarding the effect on productivity as a result of downsizing is mixed. The American Management Association surveyed 700 companies that had downsized in the 1990s. In 34 percent of the cases, productivity rose, but it fell in 30 percent of them.25 Firms that increased training budgets after a downsizing were more likely to realize improved productivity.26

Example: Separation Costs for Wee Care Children’s Hospital

Let’s now consider the computation of separation costs over one year for Wee Care Children’s Hospital, a 200-bed facility that employs 1,200 people. Let’s assume that Wee Care’s monthly turnover rate is 2 percent. This represents 24 percent of the 1,200-person workforce per year, or about 288 employees. From Figure 4-3, we apply the following formulas (all costs are hypothetical):

Exit Interview (S1)

Interviewer’s time = (15 min. preparation + 45 min. interview) × $30/hour interviewer’s pay + Benefits × 288 turnovers during the year

= $8,640

Weighted average pay + benefits per terminated employee per hour = sum of the products of the hourly pay plus benefits for each employee group times the number of separating employees in that group, all divided by the total number of separations, or in this case

= (19.96 × 75) + (23.44 × 87) + (26.97 × 65) + (29.13 × 37) + (34.46 × 14) + (47.17 × 10) divided by 288

= $25.42/hour

Terminating employee’s time = 45 min. interview time × $25.42/hour weighted average pay + Benefits × 288 turnovers during the year

= $7,320.96

Total cost of exit interviews = $8,640 + $7,320.96

= $15,960.96

Administrative Functions (S2)

S2 = Time to delete each employee × HR specialist’s pay + Benefits/hour × Number of turnovers during the year

= 1 hour × $30 × 288

= $8,640

Separation Pay (S3)

Suppose that Wee Care Children’s Hospital has a policy of paying one week’s separation pay to each terminating employee. Using the weighted average pay rate of the 288 terminating employees as an example, $25.42/hour × 40 hours/week = $1,016.80 average amount of separation pay per employee terminated.

Total Separation Pay = $1,016.80 × 288

= $292,838.40

Let’s assume that because of Wee Care’s poor experience factor with respect to terminated employees’ subsequent claims for unemployment benefits, the state unemployment tax rate is 5.4 percent, as compared with a base rate of 5.0 percent. Let us further assume that turnovers occur, on the average, after four and a half months (18 weeks). If the weighted average pay + benefits of terminating employees is $25.42 per hour, and Wee Care pays an average of 35 percent of base pay in benefits, the weighted average pay alone is $16.52 per hour ($25.42 minus 35 percent). Over 18 weeks, the direct pay per terminating employee exceeds $10,000.

The dollar increase in unemployment tax incurred because of Wee Care’s poor experience factor is therefore as follows:

(5.4% – 5.0%) × [$10,000 × (1,200 + 288)]

= (0.004) × [$10,000 × 1,488]

= $59,520 [Penalty]

+ (5.4%) × ($10,000 × 288)

= $155,520 [Additional Tax]

Total increase = $59,520 + $155,520

= $215,040

Now that we have computed all four cost elements in the separation cost category, total separation costs (Σ S1, S2, S3, S4) can be estimated. This figure is as follows:

ST = S1 + S2 + S3 + S4

= $15,960.96 + $8,640 + $292,838.40 + $215,040

= $532,479.36

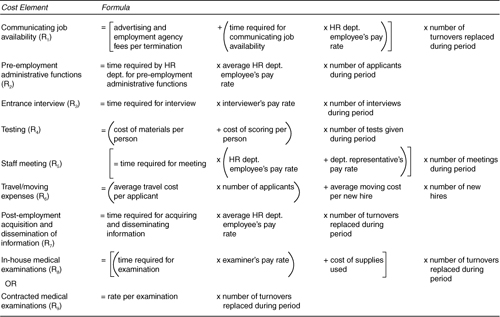

Replacement Costs

As shown in Figure 4-2, employees who replace those who leave are acquisitions. The overall value, or payoff, of those acquisitions depends on three factors: their quantity, quality, and cost. Replacement costs, as described in the following paragraphs, reflect only the quantity and cost of acquisitions, not their quality. We address the issue of staffing quality beginning in Chapter 8, “Staffing Utility: The Concept and Its Measurement.”

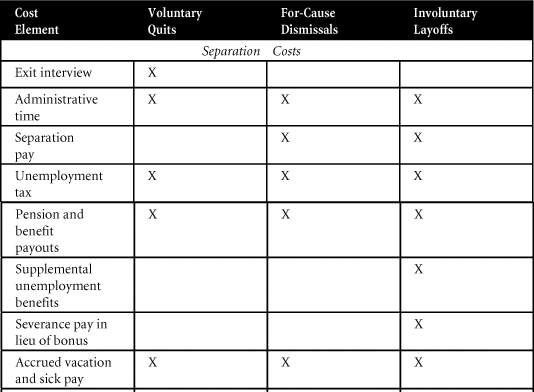

Replacement costs are incurred by an organization when it replaces a terminated employee. Figure 4-4 shows the cost elements and the formulas for estimating them. As the figure indicates, there are eight categories of replacement costs:

- Communication of job availability

- Pre-employment administrative functions

- Entrance interviews

- Testing

- Staff meetings

- Travel/moving expenses

- Post-employment acquisition and dissemination of information

- Employment medical exams

Figure 4-4. Measuring replacement costs.

The costs of communicating job availability vary by type of job and targeted labor market. Depending on the methods used in recruitment, these costs may range from the cost of an advertisement on the web, to employment agency fees paid by the employer.27 Typically, these costs can be obtained from existing accounting records. If this communication process requires time from HR department employees, the cost of their time should also be included in replacement costs.

Administratively, several tasks are frequently undertaken in selecting and placing each new employee—for example, accepting applications, screening candidates, and checking references. These procedures can be expensive. For example, a simple background investigation that includes verification of last educational degree, a check with the last two employers, a five-year criminal check, and verification of the social security number costs only about $100. However, an extensive check that includes the previous items plus interviews with previous employers, teachers, neighbors, and acquaintances can run $15,000 or more. Unfortunately, organizational information systems do not routinely document the time required to perform these activities. However, the methods described earlier for estimating exit interview time requirements can be used to estimate the time needed for pre-employment administrative functions.

Virtually all organizations use entrance interviews to describe jobs, to communicate employee responsibilities and benefits, and to make some general assessments of candidates. The costs incurred when completing entrance interviews are a function of the length of the interview, pay rates of interviewers involved, and the number of interviews conducted. Valid staffing procedures can reduce future turnover and improve future employee performance. Decision makers should consider both costs and benefits. This chapter focuses on costs; Chapter 10 shows how to calculate the benefits from valid staffing procedures.

Many firms use pre-employment testing of some sort—for example, aptitude, achievement, drug, and honesty testing. To account properly for the costs of these activities, consider the costs of materials and supplies and the cost of scoring the tests. The costs of materials and scoring for aptitude, achievement, and honesty tests are often less than $25 per candidate. Drug testing costs roughly $45 to $65 for a simple screening test,28 but confirming a positive test with more accurate equipment—a step recommended by most specialists—costs an additional $50 to $75.

For some classes of employees, especially top-level managers or other professionals, meetings or conferences may be held between the HR department and the department holding the vacant position. The estimated time for this meeting, multiplied by the sum of the pay and benefits rates for all attendees, provides a measure of this element of replacement costs. Travel and moving expenses can be extremely costly to organizations that pay these costs. Travel costs for candidates from a local labor market are minimal (carfare, parking, tolls), but travel costs for candidates who must fly in and stay in a hotel can average more than $1,500. Moving expenses can cover a range of elements, including mortgage differentials, lease-breaking expenses, company purchase of the old house, costs of moving personal effects from the old to the new location, closing costs, hook-up fees for utilities, and more. “Fully loaded” moving costs for middle managers average about $45,000 to $50,000, whereas a complete relocation package for executives averages about $70,000 per move.29

The seventh category of replacement costs is post-employment acquisition and dissemination of information. Pertinent information for each new employee must be gathered, recorded, and entered into various subsystems of an HR information system (for example, employee records, payroll files, benefits records). If flexible, cafeteria-style benefits are offered by an organization, an HR specialist could spend considerable time in counseling each new employee. The costs of this process can be estimated by calculating the time required for this counseling and multiplying it by the wage rates of employees involved. To compute the total cost of acquiring and disseminating information to new employees, multiply this cost by the number of acquisitions.

Pre-employment medical examinations are the final element of replacement costs. The extent and thoroughness—and, therefore, the cost—of such examinations varies greatly. Some organizations do not require them at all, some contract with private physicians or clinics to provide this service, and others use in-house medical staff. If medical examinations are contracted out, the cost can be determined from existing accounting data. If the exams are done in-house, their cost can be determined based on the supplies used (for example, x-ray film and laboratory supplies) and the staff time required to perform each examination. If the new employee is paid while receiving the medical examination, his or her rate of pay should be added to the examiner’s pay rate in determining total cost. The following example estimates replacement costs for a one-year period based on Figure 4-4 for Wee Care Children’s Hospital.

Job Availability (R1)

Assume that fees and advertisements average $350 per turnover, that three more hours are required to communicate job availability, that the HR specialist’s pay and benefits total $30 per hour, and that 288 turnovers are replaced during the period. Therefore:

R1 = [$350 + (3 × $30)] × 288

= $126,720

Pre-Employment Administrative Functions (R2)

Assume that pre-employment administrative functions to fill the job of each employee who left comprise five hours. Therefore:

R2 = 5 × $30 × 288

= $43,200

Assume that, on the average, three candidates are interviewed for every one hired. Thus, over the one-year period of this study, 864 (288 × 3) interviews were conducted, each lasting one hour. Therefore:

R3 = 1 × $30 × 864

= $25,920

Testing (R4)

Assume that aptitude tests cost $12 per applicant for materials and another $12 per applicant to score, and that, as a matter of HR policy, Wee Care uses drug tests ($45 per applicant) as part of the pre-employment process. The cost of testing is therefore as follows:

R4 = ($24 + $45) × (288 × 3)

= $59,616

Staff Meeting (R5)

Assume that each staff meeting lasts one hour; that the average pay plus benefits of the new employee’s department representative is $42; and that, for administrative convenience, such meetings are held, on average, only once for each three new hires (288 / 3 = 96). Therefore:

R5 = ($30 + $42) × 96

= $6,912

Travel/Moving Expenses (R6)

Assume that Wee Care pays moving expenses of $50,000, on average, for only one of every eight new hires. Therefore:

R6 = [$95 × (288 × 3)] + ($50,000 × 36)

= $56,160 + $1,620,000

= $1,882,080

Post-Employment Acquisition and Dissemination of Information (R7)

Assume that two hours are spent on these activities for each new employee. Therefore:

R7 = 2 × $30 × 288

= $17,280

Pre-Employment Medical Examination (R8 and R9)

Assume that if the medical examinations are done at the hospital (in-house), each exam will take one hour; the examiner is paid $55 per hour; x-rays, laboratory analyses, and supplies cost $135; and 288 exams are conducted. Therefore:

R8 = [(1 × $55) + $135] × 288

= $54,720

If the exams are contracted out, let’s assume that Wee Care will pay a flat rate of $250 per examination. Therefore:

R9 = $250 × 288

= $72,000

Wee Care therefore decides to provide in-house medical examinations for all new employees, so R9 does not apply in this case. Total costs (RT) can now be computed as the sum of R1 through R8:

RT = $126,720 + $43,200 + $25,920 + $59,616 + $6,912 + $1,882,080 + $17,280 + $54,720

RT = $2,216,448

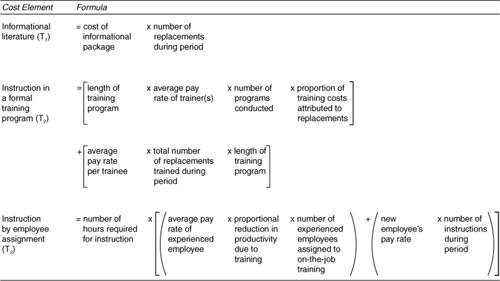

Training Costs

In virtually all instances, replacement employees must be oriented and trained to a standard level of competence before assuming their regular duties. As discussed in Chapter 11, “Costs and Benefits of HR Development Programs,” this often involves considerable expense to an organization. For the present, however, assume that all replacement employees receive a total of 2 full days (16 hours) of new employee orientation from an HR department representative. After that, they are either placed in a formal training program, assigned to an experienced employee for some period of on-the-job training, or both. Figure 4-5 shows the cost elements and computational formulas for this category of turnover costs. The three major elements of training costs are informational literature plus new employee orientation, instruction in a formal training program, and instruction by employee assignment.

Figure 4-5. Measuring training costs.

The cost of any informational literature provided to replacement employees must be considered a part of orientation and training costs. Unit costs for those items may be obtained from existing accounting records. Multiplying the unit costs by the number of replacement employees hired during the period yields the first element of training costs. The cost of orientation includes the pay and benefits of the new employees who attend, as well as the pay and benefits of the HR representative who provides the orientation training times the number of hours of training.

New employees may also be involved in a formal training program. The overall cost of the training program depends on the cost of two major components: costs associated with trainers and costs associated with trainees. Whereas an organization incurs 100 percent of the costs associated with training replacements for employees who leave, the cost associated with trainers depends on the extent to which formal training is attributable to turnover. It is important, therefore, to distinguish the proportion of trainees who are replacements for employees who left, from the reminder who are in training due to other factors, such as planned expansion of the workforce. For the sake of simplicity, the costs of facilities, food, and other overhead expenses have not been included in these calculations.

Instead of, or in addition to, instruction in a formal training program, new employees may also be assigned to work with more experienced employees for a period of time or until they reach a standard level of competence. The overall cost of this on-the-job training must be determined for all replacement employees hired during the period, for it is an important element of training costs.

Notice that, in Figure 4-5, the cost of reduced productivity of new employees while they are learning is not included as an element of overall training costs. This is not because such a cost is unimportant. On the contrary, even if an organization staffs more employees to provide for a specified level of productivity while new employees are training, the cost of a decrease in the quantity and quality of goods or services produced is still very real. Less experienced employees may also cause an increase in operating expenses because of inefficient use of supplies and equipment. Other elements of lost productivity and lost business include factors such as additional overtime to cover one or more vacancies, cost of temporary help, the offsetting effects of wages and benefits saved due to the vacancy, and the cost of low morale among remaining employees.

At high levels in organizations, and in other jobs where relationships with customers, leads, and contacts are critically important, the economic cost of business lost (that is, “opportunities foregone”) may be substantial. On top of that, there may also be “ripple effects” associated with an employee’s departure so that other employees follow him or her out the door. Situations such as these are especially prevalent when employee “stars” or “A-level” players depart and convince others to follow them. Executive recruiters call these situations “lift-outs.” As BusinessWeek noted, “In a way, lift-outs are the iTunes of the merger world: Why buy the whole CD when all you really want are its greatest hits?30 They can be especially costly, not to mention that they create huge gaps in staffing. They tend to occur when tightly knit groups or networks of employees (coworkers, former colleagues, classmates, or friends) decide to leave en masse.31

All of these costs are important. In the aggregate, they easily could double or triple the costs tallied thus far. When they can be measured reliably and accurately, they certainly should be included as additional elements of training costs. The same is true for potential productivity gains associated with new employees. Such gains serve to offset the costs of training. However, in many organizations, especially those providing services (for example, credit counseling, customer services, and patient care in hospitals), the measurement of these costs or gains is simply too complex for practical application. At the same time, these costs are seldom zero, and it is probably better to include a consensus estimate of their magnitude from a knowledgeable group of individuals than to assume either that they do not exist or that the cost is zero.

Now let us estimate the total cost of training employee replacements at Wee Care. Using the formulas shown in Figure 4-5, Wee Care estimates the following costs over a one-year period.

Informational Literature and New-Employee Orientation (T1)

Assume that the unit cost of informational literature is $20 and that 288 employees are replaced. Each of the 288 replacements, at an average pay rate plus benefits of $25.42 per hour (see the earlier computation of S1), attends 16 hours (two days) of general orientation to the hospital. This is provided in a two-day meeting that is held ten times per year, conducted by an HR representative, who receives $30 per hour in pay and benefits. The total cost of informational literature and new-employee orientation is, therefore, as follows:

T1 = ($20 × 288) + (16 × $25.42 × 288) + (10 × 16 × $30)

= $127,695.36

Instruction in a Formal Training Program (T2)

New-employee training at Wee Care is conducted 10 times per year, and each training program lasts 40 hours (1 full week). The average pay plus benefits for instructors is $48 per hour, the average pay and benefits rate for trainees is $25.42 per hour, and of the 576 employees trained on the average each year, half are replacements for employees who left voluntarily or involuntarily. The total cost of formal training attributed to employee turnover is, therefore, as follows:

T2 = (40 × $48 × 10 × 0.50) + ($25.42 × 288 × 40)

= $9,600 + $292,838.40

= $302,438.40

Instruction by Employee Assignment (T3)

To ensure positive transfer between training program content and job content, Wee Care requires each new employee to be assigned to a more experienced employee for an additional week (40 hours). Experienced employees average $35 per hour in wages and benefits, and their own productivity is cut by 50 percent while they are training others. Each experienced employee supervises two trainees. The total cost of on-the-job training for replacement employees is, therefore, as follows:

T3 = 40 × [($35 × 0.50 × 144) + ($25.42 × 288)]

= 40 × ($2,520 + $7,320.96)

= 40 × $9,840.96

= $393,638.40

Total training costs can now be computed as the sum of T1, T2, and T3:

TT = $127,695.36 + $302,438.40 + $393,638.40

= $823,772.16

Performance Differences Between Leavers and Their Replacements

A final factor to consider in the tally of net turnover costs is the uncompensated performance differential between employees who leave and their replacements. We call this difference in performance (DP). DP needs to be included in determining the net cost of turnover because replacements whose performance exceeds that of leavers reduce turnover costs, and replacements whose performance is worse than that of leavers add to turnover costs.

To begin measuring DP in conservative, practical terms, compute the difference by position in the salary range between each leaver and his or her replacement. Assume that performance differentials are reflected in terms of deviations from the midpoint of the pay grade of the job class in question. Each employee’s position in the salary range is computed as a “compa-ratio”; that is, salary is expressed as a percentage of the midpoint of that employee’s pay grade. If the midpoint of a pay grade is $50,000 (annual pay), for example, an employee earning $40,000 is at 80 percent of the midpoint. Therefore, his or her compa-ratio is 0.80. An employee paid $50,000 has a compa-ratio of 1.0 (100 percent of the midpoint rate of pay), and an employee paid $60,000 has a compa-ratio of 1.2 because he or she is paid 120 percent of the midpoint rate of pay. Compa-ratios generally vary from 0.80 to 1.20 in most pay systems.32

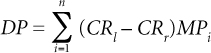

To compute DP, use the following formula:

Here, DP is difference in performance between leaver and replacement, ![]() is summation over all leavers and their replacements, CRl is the compa-ratio of the leaver, CRr is the compa-ratio of the replacement, and MPi is the annual rate of pay at the midpoint of the pay grade in question. Consider the following example:

is summation over all leavers and their replacements, CRl is the compa-ratio of the leaver, CRr is the compa-ratio of the replacement, and MPi is the annual rate of pay at the midpoint of the pay grade in question. Consider the following example:

CRl = 0.80 CRr = 1.0 MPi = $50,000

DP = (0.80 – 1.0) × $50,000

DP = (–0.20) × $50,000

DP = –$10,000

DP is therefore subtracted from total turnover costs because the firm is gaining an employee whose performance is superior to that of the employee who was replaced.

If the compa-ratio of the leaver is 1.0, that of the replacement is 0.80, and the pay-grade midpoint is $50,000, then DP = $10,000. These costs are added to total turnover costs because the leaver was replaced by a lesser performer.

Why are differences in performance assumed to covary with differences in pay? Actually, this assumption is true only in a perfectly competitive labor market.33 In a perfectly competitive labor market, every worker earns the marginal revenue product accrued to the firm from his or her labor. Thus, the firm is indifferent to workers whose compa-ratios are 0.80, 1.0, or 1.20 because each worker is paid exactly what he or she is “worth.”

Many entry-level jobs (for example, management analysts) approximate conditions in which it is reasonable to assume that compa-ratio differences reflect performance differences. Above the entry level, however, labor markets are often imperfect because workers develop what economists call “firm-specific human capital.”34 Workers who have specific job knowledge that their firms value (for example, in banking, automobiles, or computers) tend to command higher wages. However, their value is reflected only partly in their higher wages. Wages reflect what economists call “opportunity costs,” or the value of a worker’s second-best employment opportunity. Competitors are able to offer only a wage that reflects the economic value of a worker to them. Therefore, opportunity costs and the wage rates paid to valued employees tend to reflect only the portion of a worker’s economic value that is easily transferable from one employer to another (that is, “generic”). The portion of an employee’s value that is not easily transferable, the firm-specific component, typically is reflected only partially in employee wages, if at all. Thus, the economic value of workers with firm-specific human capital is above their wage (opportunity cost) level but can be assumed to be proportionate to these wages.

If an employee with substantial amounts of firm-specific human capital leaves the firm and is replaced by a worker who lacks such firm-specific human capital, the replacement will receive a lesser wage. However, if a poor performer leaves and is replaced by a worker with more human capital, albeit non-firm-specific, the replacement will receive a higher wage than the leaver.35 The difference in pay between leavers and their replacements thus represents an indicator, although an imperfect one, of the “uncompensated performance differential” due to firm-specific human capital, and it should be considered when determining the net costs of turnover.

The assumption that excess value to the firm is a function of wages paid and that excess value and wages covary in a linear (straight-line) fashion is conservative. In practice, the relationship can be curvilinear (positive or negative). For our purposes, however, the conservative assumption of a linear relationship between excess value and wages is appropriate. At the same time, higher (lower) wages paid to a replacement employee represent an additional, ongoing cost (or saving) to an organization. It is appropriate to calculate such a pay differential, for it is part of the differential value of the replacement, relative to the employee who left. Although an offsetting strategic value may justify paying a replacement more, that is often a subjective estimate by decision makers.

For Wee Care, assume that the net DP = $200,000. On average, therefore, the firm hired slightly poorer performers than it lost. The following equation, which uses the four major components of employee turnover, represents the total cost of employee turnover:

Total cost of turnover = ST + RT + TT + DP

Here, ST is total separation costs, RT is total replacement costs, TT is total training costs, and DP is net differential performance between leavers and their replacements. For Wee Care, the total cost of 288 employee turnovers during a one-year period was as follows:

$467,967.36 + $2,216,448 + $823,772.16 + $200,000

= $3,508,387.50

This represents a cost of $12,166.90 for each employee who left the hospital.

The Costs of Lost Productivity and Lost Business

In several places earlier in this chapter, we mentioned that it is useful to include the costs of lost productivity and lost business in the fully loaded cost of employee turnover, if it is possible to tally such costs accurately. Seven additional cost elements might be included, as follows:36

• The cost of additional overtime to cover the vacancy (wages + benefits × number of hours of overtime)

• The cost of additional temporary help (wages + benefits × hours paid)

• Wages and benefits saved due to the vacancy (these are subtracted from the overall tally of turnover costs)

• The cost of reduced productivity while the new employee is learning the job (wages + benefits × length of the learning period × percentage reduction in productivity)

• The cost of lost productive time due to low morale of remaining employees (estimated as aggregate time lost per day of the work group × wages + benefits of a single employee × number of days)

• The cost of lost customers, sales, and profits due to the departure (estimated number of customers × gross profit lost per customer × profit margin in percent)

• Cost of additional (related) employee departures (if one additional employee leaves, the cost equals the total per-person cost of turnover)

In terms of analytics, one final caution is in order: Don’t be misled by variability across departments or business units that are based on small numbers. After all, if a six-person department loses two employees, that’s a 33 percent turnover rate. We noted in Chapter 2, “Analytical Foundations of HR Measurement,” the dangers associated with generalizing from small samples that are not representative of the larger population they are designed to represent. In the case of small-sample turnover statistics, to make the sample more representative, it might make sense to segment employee turnover into broader categories that include larger numbers of employees.

Remember, the purpose of measuring turnover costs and using analytical strategies to reveal their implications is to improve managerial decision-making. Consider a brief example of one such an analysis.37 Based on the model shown in Figure 4-2, the researchers developed an analytical model that captured the value associated with employee separations (turnover) and acquisitions (hires) over a four-year period. Their model estimated three components in each time period:

• Movement costs: The costs associated with employee separations and acquisitions

• Service costs: The pay, benefits, and associated expenses required to support the workforce

• Service value: The value of the goods and service produced by the workforce

Then they estimated the dollar-valued implications of three different pay plans (equal pay increases plus two types of pay-for-performance plans) and of the subsequent separation and acquisition patterns over the four years. They did so by subtracting the movement costs and service costs from the service value. In short, they subtracted each pay plan’s costs from its benefits.

Traditional compensation-cost analysis suggested that a strong link between pay and performance would be unwise, given its extreme cost. When the potential benefits of workforce value were accounted for, however, a different conclusion emerged. By fully incorporating both costs and benefits into their model, the researchers showed that even under the most conservative assumptions, pay-for-performance was a valuable investment, with potentially very high payoffs for the firm, in part because it caused poor performers to leave more often and good performers to leave less often. This reinforces a point we made at the beginning of the chapter: Turnover is only one part of a family of external moves. Adopting a broader perspective is a wise strategy indeed.

Process

Organizational budgeting practices sometimes provide a natural opportunity to use the costs of employee turnover as part of a broader framework to demonstrate tangible economic payoffs from effective management practices. When line managers complain that they cannot keep positions filled or that they cannot get enough people to join as new hires, it is a prime opportunity to elevate the conversation.

Revenue at Superior Energy Services in New Orleans is based on billable hours. That fact gave Ray Lieber, the HR vice president, an opportunity to portray every separation as lost revenue. Nearly half of the separations were skilled operators or supervisors with high impact on revenue. Then he made the case for an investment in statistical modeling to predict how to reduce turnover. He discovered that the most significant factor was not higher pay or benefits, but one-on-one coaching from supervisors. Superior Energy invested in supervisor coaching training and saw turnover drop from 34 percent to about 27 percent.38

Thrivent Financial for Lutherans in Minneapolis had always assumed that the more experience a new hire had in the job he or she was hired into, the less likely that new hire was to leave, but it found just the opposite when it analyzed turnover data. That gave HR leaders at Thrivent the chance to get the attention of line management and to invest in studies to discover why those with more experience were more likely to leave. Similarly, at Wawa, Inc., a Pennsylvania food service and convenience company, leaders had suspected that hourly wage was the biggest factor in turnover among clerks, but careful analysis found that the most significant turnover predictor was hours worked. Those working more than 30 hours per week were classified as full-time and separated less. This discovery opened the door to moving from 30 percent part-time to 50 percent full-time, reducing turnover rates by 60 percent.39

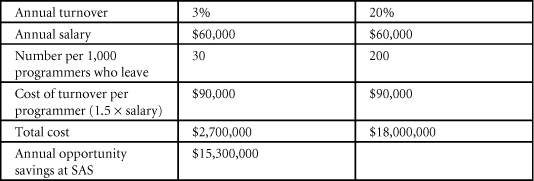

As a final example, consider the SAS Institute of Cary, North Carolina. SAS is renowned for its low voluntary turnover rate among computer programmers. In an industry that routinely experiences 20 percent voluntary turnover per year among programmers, at SAS, turnover runs about 3 percent per year. It does that largely through its enlightened management practices. Those practices are founded on the idea that in an intellectual capital business, attracting and retaining talent is paramount, and the way to attract and retain good people is to give them interesting work and interesting people to do it with, and treat them like the responsible adults they are.

SAS is justifiably famous for its pleasant physical work environment and generous, family-friendly benefits. Those benefits include an on-site 7,500-square-foot medical facility and a full-indemnity health plan that includes vision, hearing, and dental care; free physical exams; and free mammography. It also provides on-site Montessori day care, a fitness center, soccer, and softball fields. All this is free to employees and their families. The company even provides towels and launders exercise clothes—also for free. Finally, it provides elder care, domestic-partner benefits, and cafeterias with subsidized meals.40

Suppose that a line leader addresses the following question to HR leaders: “I’m happy that our turnover among programmers is 3 percent, but are we spending too much to keep them, and is it worth it?” In answering that very reasonable question, an HR leader might begin by reviewing the company’s business model. In brief, it is as follows.41

SAS relies on annual product renewals from its clients, who use its software for deep analysis of their organizational databases. SAS also relies on employees for innovations and services that are tailored to those clients’ particular industry requirements and their unique competitive positions in their industries. This means that client relationships with SAS advisers need to be based on a thorough, shared understanding about industry-specific competition and on long-term trust. This may be more important for SAS than for its competitors, whose business models are based more on software purchases than renewable licenses and whose value proposition is not so deeply dependent on close and well-informed relationships with clients.

One way that SAS creates the capability, opportunity, and motivation to achieve this kind of deep, common, client-focused synergy is by creating an employment model that attracts and motivates programmers, designers, and client advisers to join and stay for the long run. This is a distinctive value proposition because a long-term employment deal is unusual in professions where the norm is to move from project to project, often changing employers many times in a few years to find the most interesting work or a higher paycheck.

The HR leader might then present the cost implications of that 17 percent difference in employee turnover between SAS and the software industry. Table 4-2 includes some hypothetical calculations.

Table 4-2. Annual Opportunity Savings from Lower Employee Turnover among Programmers: SAS Versus the Software Industry

Of course, the annual opportunity savings does not include the incremental, yearly cost to SAS of providing such generous benefits to its employees. Assume, however, that the annual cost of benefits per SAS employee is as high as 50 percent of salary (compared to a 2008 U.S. average of 39 percent).42 Its incremental, yearly cost, relative to its competitors’, is thus roughly 11 percent higher. The total annual opportunity savings to SAS as a result of lower employee turnover may be viewed as an annuity that helps to pay for the benefits that keep employee turnover low. Because it takes a long time for a new employee to develop the kind of shared understanding and high level of trust with clients that is central to the SAS business model, retaining talent truly is critical to achieving the company’s strategic objectives. The answer to the line leader’s original question is that SAS’s investments in generous employee benefits are likely to be worth it.

Exercise

Software that calculates answers to one or more of the following exercises can be found at http://hrcosting.com/hr/.

- Ups and Downs, Inc., a 4,000-employee organization, has a serious turnover problem, and management has decided to estimate its annual cost to the company. Following the formulas presented in Figures 4-3, 4-4, and 4-5, an HR specialist collected the following information. Exit interviews take about 45 minutes (plus 15 minutes preparation); the interviewer, an HR specialist, is paid an average of $31 per hour in wages and benefits; and, over the past year, Ups and Downs, Inc., experienced a 27 percent turnover rate. Three groups of employees were primarily responsible for this: blue-collar workers (40 percent), who make an average of $33.20 per hour in wages and benefits; clerical employees (36 percent), who make an average of $18.50 per hour; and managers and professionals (24 percent), who make an average of $44.75 per hour. The HR department takes about 90 minutes per terminating employee to perform the administrative functions related to terminations; on top of that, each terminating employee gets two weeks’ severance pay. All this turnover also contributes to increased unemployment tax (old rate = 5.0 percent; new rate = 5.4 percent); because the average taxable wage per employee is $22.90, this is likely to be a considerable (avoidable) penalty for having a high turnover problem.

It also costs money to replace those terminating. All pre-employment physicals are done by Biometrics, Inc., an outside organization that charges $250 per physical. Advertising and employment-agency fees run an additional $550, on average, per termination, and HR specialists spend an average of four more hours communicating job availability every time another employee quits. Pre-employment administrative functions take another two and a half hours per terminating employee, and this excludes pre-employment interview time (one hour, on average). Over the past year, Ups and Downs, Inc., records also show that, for every candidate hired, three others had to be interviewed. Testing costs per applicant are $14 for materials and another $14 for scoring. Travel expenses average $85 per applicant, and one in every ten new hires is reimbursed an average of $55,000 in moving expenses. For those management jobs being filled, a 90-minute staff meeting is also required, with a department representative (average pay and benefits of $37.75 per hour) present. In the past year, 17 meetings were held. Finally, post-employment acquisition and dissemination of information takes 75 minutes, on average, for each new employee.

And of course, all these replacements have to be oriented and trained. Informational literature alone costs $19 per package, and a formal orientation program run by an HR specialist takes 2.5 days (20 hours) spread over the first two months of employment. New employees make an average of $22.50 per hour in wages and benefits. After that, a formal training program (run 12 times last year) takes four 8-hour days, and trainers make an average of $46 per hour in wages and benefits. About 65 percent of all training costs can be attributed to replacements for those who left. Finally, on-the-job training lasts three 8-hour days per new employee, with two new employees assigned to each experienced employee (average pay and benefits = $36.25 per hour). During training, each experienced employee’s productivity dropped by 50 percent. Net DP was + $210,000. What did employee turnover cost Ups and Downs, Inc., last year? How much per employee who left? (Use the software available from http://hrcosting.com/hr/ for all computations.)

References

1. Morrison, Scott, “Google Searches for Staffing Answers,” The Wall Street Journal, May 19, 2009, B1.

2. United States Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Data Bases and Tables, www.bls.gov/jlt/. Reports can be generated at http://data.bls.gov:8080/PDQ/outside.jsp?survey=jt.

3. Wal-Mart Corporation, Form 10-K, January 2010. www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/104169/000119312510071652/d10k.htm.

4. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

5. McCarthy, Ryan, “Walmart Tops the Fortune 500 List Again,” Huffington Post, June 8, 2010, www.huffingtonpost.com/2010/04/15/walmart-tops-fortune-500_n_538600.html.

6. Boudreau, J. W., and C. J. Berger, “Decision-Theoretic Utility Analysis Applied to Employee Separations and Acquisitions,” Journal of Applied Psychology Monograph 70, no. 3 (1985): 581–612.

8. Boudreau, John W., Retooling HR: How Proven Business Models Can Improve Human Capital Decisions (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Business Press, 2010).

9. Martin, D. C., and K. M. Bartol, “Managing Turnover Strategically,” Personnel Administrator 30, no. 11 (1985): 63–73.

10. Tyler, Richard, “Workers Over 60 Are Surprise Key to McDonald’s Sales,” Telegraph, August 13, 2009, www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/retailandconsumer/6017391/Workers-over-60-are-surprise-key-to-McDonalds-sales.html.

13. Cascio, Wayne F., Employment Downszing and Its Alternatives (Washington, D.C.: SHRM Foundation, 2009).

14. Hulin, C. L., “Integration of Economics and Attitude/Behavior Models to Predict and Explain Turnover,” paper presented at Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, Atlanta, Ga., 1979.

15. Branch, S., “You Hired [’]em, but Can You Keep [’]em?” Fortune (November 9, 1998): 247–250.

16. Solomon, J., “Companies Try Measuring Cost Savings from New Types of Corporate Benefits,” The Wall Street Journal, December 29, 1988, B1.

17. Hewlett, S. A., and C. B. Luce, “Off-Ramps and On-Ramps: Keeping Talented Women on the Road to Success,” Harvard Business Review 83 (March 2005): 43–54.

18. Johnson, A. A., “The Business Case for Work-Family Programs,” Journal of Accountancy 180, no. 2 (1995): 53–58.

19. Smith, H. L., and W. E. Watkins, “Managing Manpower Turnover Costs,” Personnel Administrator 23, no. 4 (1978): 46–50.

20. Dooney, J., “Cost of Turnover,” November 2005, retrieved from www.shrm.org/research on February 6, 2006.

21. Allbusiness.com, “Severance Pay,” retrieved from www.Allbusiness.com on August 8, 2006.

22. Milkovich, G. T., J. M. Newman, and B. Gerhart, Compensation, 10th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2011).

23. Needleman, S. E., “Feeling Blue about Pink-Slip Taxes,” The Wall Street Journal, April 6, 2010, B11.

24. Svaldi, A., “Bosses Will Pay for Layoffs,” The Denver Post, April 18, 2010, 1K and 10K.

25. This data was reported in Cravotta, R., and B. H. Kleiner, “New Developments Concerning Reductions in Force,” Management Research News 24, no. 3–4 (2001): 90–93.

26. Appelbaum, S. H., S. Lavigne-Schmidt, M. Peytchev, and B. Shapiro, “Downsizing: Measuring the Costs of Failure,” Journal of Management Development 18, no. 5 (1999): 436–463.

27. Cascio, W. F. (2006). Managing Human Resources: Productivity, Quality of Work Life, Profits (6th ed, Ch. 6). Burr Ridge, IL: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

28. Expomed.com (2006). Drug Testing. Retrieved from www.Expomed.com on August 10, 2006.

29. Hansen, F. (Nov. 2002). Reigning in relocation costs. Work force. Downloaded from www.work force.com on August 24, 2004.

30. McGregor, J. (Dec. 18, 2006). I can’t believe they took the whole team. Business Week, p. 120, 122.

31. Wysocki, B., Jr. (March 30, 2000). Yet another hazard of the new economy: The Pied Piper effect. The Wall Street Journal, p. A1; A16.

32. Milkovich, G. T., & Newman, J. M. (2008). Compensation (9th ed.). Burr Ridge, IL: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

33. Hirschey, M. (2006). Fundamentals of Managerial Economics (8th ed.) Mason, OH: South-Western Thompson Learning.

34. Becker, G. S. (1964). Human Capital. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

35. Lazear, E. P. (1998). Personnel Economics for Managers. NY: Wiley.

37. Sturman, M. C., Trevor, C. O., Boudreau, J. W., & Gerhart, B. (2003). Is it worth it to win the talent war? Evaluating the utility of performance-based pay. Personnel Psychology, 56, 997-1035.

38. Bill Roberts. “Analyze This.” HR Magazine. October, 2009. 35-41.

40. O’Reilly, C. A. III, & Pfeffer, J. (2000). Hidden Value. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

41. Boudreau, J. W., & Ramstad, P. (2007). Beyond HR: The New Science of Human Capital. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

42. Society for Human Resource Management. (2008). 2008 employee benefits. Alexandria, VA: Society for Human Resource Management.