Susanne Lesk, Eva Lavric and Martin Stegu

13Multilingualism in business: Language policies and practices

2.Language practices in business

3.Language policies in business

4.Insights from other selected disciplines

1Introduction

Today’s working environments are often culturally heterogeneous and linguistically diverse. As a result, language-policy-related decisions affect employees in their daily work, whether directly or indirectly. The current research interest in multilingual business contexts, and in people working within them, is broad and highly interdisciplinary. Traditionally, multilingual phenomena have been an object of study for socio- and contact linguistics, but also for psychology, sociology, ethnology and anthropology, with researchers from these disciplines occasionally investigating linguistic contact situations in organisations through very different theoretical lenses and with very different empirical instruments. In this contribution we follow a linguistic approach, but we try also to think out of the box and learn from research done elsewhere.

In the business context, language-policy decisions emerging from multilingual working environments are a field of study within applied (socio)linguistics, but not only there. Other disciplines in which multilingualism in business is being researched are management and organisation studies, political science, and economics. In fact, researchers from all those fields have discovered a common research topic: language and languages policies in businesses and the economy. We therefore begin this chapter by introducing the concept of language practices in business and presenting some questions, research and findings from a (socio)linguistic perspective. Next, we define the central concepts in the realm of corporate language policies and present the related linguistic research. We then widen our scope to continue with some findings from the other disciplines mentioned above. Finally, we propose some further directions for future research based on the state of the art presented in this chapter.

Throughout, we try to link language policies and practices to – and, at the same time, demarcate them from – the topic of language needs treated in Chapter 12. In fact, language needs, policies and practices are all highly intertwined (see Fig. 13.1). Attempting to separate the concepts is thus somewhat artificial. If companies strive for a systematic approach to language policy (e.g., the choice of a common corporate language, language-related declarations in the mission statement), they will have to base their considerations on a profound language needs analysis including the organisational and individual level (an example of the link between needs and policies). Lived linguistic practices reflect the language needs met within a company, whereas desired linguistic practices would address unmet needs (an example of the link between needs and practices). If companies do not have an explicit language policy, they will certainly have an implicit one (see Section 3.4 below) which impacts on language practices and vice versa (an example of the link between policies and practices). Of course, in specific businesses we may observe contradictions between the three areas, just as we may find cases where policies, practices and needs are perfectly aligned.

Moreover, much published literature on languages in business does not clearly separate needs, policies and practices. Research can focus primarily on only one of the three aspects, but it will inevitably touch on the three domains and produce closely related findings in them all. Therefore Chapters 12 and 13 are complementary, and the respective bibliographies are of potential interest for researchers interested in any of the three aspects.

Let us start here with a provisional distinction between language policies and practices, that is, some ideas about possible distinctions, with the aim of preparing the ground for further reflections. At first sight, one would be inclined to draw the line between language policies and practices on the basis of distinctions such as the following:

–Purposeful vs. unintended;

–Long/medium-term vs. ad hoc;

–Oriented towards the future vs. grounded in the past;

–Concerning a whole company vs. concerning an individual or a small group;

–Explicitness vs. implicitness;

–Coming from the management (top-down) vs. emerging from the staff (bottom-up).

As a first approximation, one could thus say that the more an action or a choice is purposeful, long-term, future-oriented, company-wide, explicit and top-down, the more it is policy; while the more it is non-reflected, ad hoc, individual, implicit, and bottom-up, the more it is practice.

But that is not the way the problem is being approached in current research about languages in business. As we will see below (Section 3), research about language policies in companies and organisations has already come to include all the non-purposeful, ad hoc, past-grounded, small-scale, implicit aspects of language choice and usage, and to define and analyse them as types of policy. This has made policies research more interesting and complex but left hardly any space for practices research, making it a subdomain of the policies realm.

Here we will suggest and adopt another type of approach that considers the policies-practices dichotomy mainly a difference in viewpoint. Under the title of practices (Section 2), we will present the descriptive aspects of sociolinguistic studies concerned mainly with the actual language use of people working in international business(es), and their explanations of that use. This will provide us with a large pool of empirical data giving a very concrete idea of the phenomena that policies-and-practices research is about.

Then, under the title of policies (Section 3), we will present research on the plans, motivations and ideologies being developed in the language sector by actors ranging from state to business, and from management to individual employees. These studies include a fine-grained discussion on terminological issues and an interesting ongoing debate on the limits of the policies concept in business language, as well as ethical and political considerations about the relationship of language and power, a central research issue of critical currents in applied linguistics (cf. Pennycook 2001).

Following that, we will call on other disciplines such as management and organisation studies and economics (Section 4), in order to consider the language question against alternative backgrounds with a view to shedding new light on certain issues. These perspectives could also considerably enrich the sociolinguistic approaches – just as, conversely, sociolinguistic concepts and findings could usefully receive greater attention in management and economics studies relating to languages (Section 5).

2Language practices in business

2.1The specific perspective of language practices research

It should be clear by now that many of the phenomena referred to as practices also belong, if seen from a slightly different perspective, to the needs and policies realms. So let us specify what this different perspective could be. Language practices in companies are at once the manifestation and the concrete answer to language needs, as well as the empirical basis and the field of action of corporate language policies. Thus, they encompass, in our definition, all choices of language or linguistic variety involved in concrete communicative acts and habits (i.e., oral or written interaction among organisational members, or between these and the company’s external stakeholders), but also human-resource management instruments (recruiting, training) dealing with language competences/ resources.

What, then, are the questions to be posed by research into linguistic practices in business? Here are some suggestions (Lavric 2008c: 43): How do companies/ organisations deal with the problem of language needs and use? Which languages and varieties are really employed in business life, by whom, with whom, in which situations and on which media? Why do companies possess, or lack the necessary competences? How do the different actors (management, employees) intervene in the design of daily practices? How far does real language practice in the company/ organisation coincide with the official language policy (if there is one)? Does language use in companies/ organisations follow meaningful patterns, and, if so, on what principles are these based? Is it possible to identify and describe something like “best practices”, and what could be the criteria for doing so?

As regards methodology, language practices are, by their very nature, susceptible to study by observation or participant observation. Researchers can (i) observe the field, (ii) observe it while at the same time working in it, or (iii), they can ask participants – employees or other actors – to observe their own language practices and pass on their perceptions. The last is often done by means of qualitative interviews (or, sometimes, questionnaires). However, in this case researchers should be aware of the self-report bias inherent in the method, and of the fact that they are not accessing language practices directly, but rather self-perceptions and participant perceptions of such practices.32 (See also Chapter 12 on language needs in business).

To the above discussion of practices and policies, we now add a list of areas of business communication with their corresponding actors. Menz and Stahl (2008: 136) distinguish five arenas of communication for a company: the internal arena, the market arena, the financial arena, the public arena and the media arena. The internal arena comprises all communication within the company or, for groups of companies, between headquarters and subsidiaries, and among subsidiaries. The market arena concerns not only sales – to sales agents and other distributors as well as to customers – but also purchases (the latter often neglected in language policies). The financial arena comprises communication with banks and financial markets. The public arena includes communication with state and regional institutions. Along with the media arena, it is also concerned with the company’s positioning in society as a whole, its communication with politicians, journalists and the wider public. Indeed, the node constituted by the enterprise is surrounded by a veritable network of relations and structures, whose branches and links are determined by power relations, and hence by differing requirements for (linguistic) compliance and adaptation.

Language practices are influenced by this organisational environment and by their relationship with policies. They may sometimes merely represent employees’ linguistic habits or they may follow and reflect explicit and/or implicit language policies (for the distinction, see Section 3.4). On occasion, they lead to the formulation of new goals for organisational language policy, and the implementation of new policy measures. Therefore, practices may either be shaped by the goals of an organisational policy – in such cases, they usually reflect language needs already met – or they may contradict policy goals, implicit or explicit. In the latter case, they could indicate needs perceived to be unmet. In either instance, language practices are ways to resolve problems in corporate communication situations, internal or external. They stem from more or less spontaneous linguistic choices in concrete linguistic contact situations between organisational stakeholders (e.g., employees, customers, suppliers).

2.2Overview of language practices research

Research into language practices in business and economics has traditionally taken place in the field of applied linguistics, within a sociolinguistic framework. What is striking about this research is that, while the questions asked and methods used do not vary greatly, its objects are diverse. It investigates, with various thematic focuses, language policies and practices in businesses (and non-profit organisations) of all sizes and structures, and in numerous locations. Thus we find empirical language practices research focusing on:

–enterprises and/or languages in a particular territory (e.g., Schweiger 2009 on Czech and Slovak in north-east Austria, Bäck 2004 on Romance languages in Upper Austria, Minkkinen and Reuter 2001 and Reuter 2003 on German in Scandinavian countries, etc.);

–small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) throughout the EU, involving major research projects such as the ELAN-Study (European Commission 2006) and the PIMLICO-Project (European Commission 2011), both funded by the European Commission;

–multinational companies and organisations (Ammon 1996; Coulmas 1996; Duchêne 2008; Bellak 2014);

–the non-profit sector (e.g., Steiner 2014 on football clubs), also in comparison with the for-profit one (Lavric 2009c, 2012a).

In contrast to the corresponding management literature on language policies, which concentrates de facto on Western Europe and the Anglophone world, linguists do not seem to be restricted to a specific geographical context. They are interested in businesses all over the world, also in African, Asian and South-American contexts, and they are working on bigger units and smaller ones, for example, continents, countries, regions and districts. Among research into European organisations, there is a strong concentration on those located in Central Europe (e.g., Austria, Switzerland, Czech Republic: Nekvapil and Nekula 2006; Bäck and Lavric 2009a–b; Nekula, Marx and Šichová 2009; Lüdi 2012) or in Romance-speaking countries (Bäck 2004; Mrázová 2005 and 2009). Recently, there has been greater research interest in the Russian context, with studies on language use and the management strategies of multinationals operating in Russia (Lechner 2010; Garstenauer 2017).

In terms of research topic and focus, we find empirical work about internal and external communication in enterprises (Vollstedt 2002; Harder 2009; Lavric 2012b). More recently, the topic of globalisation has entered academic linguistic discourse in debates about cases of linguistic standardisation (e.g., English only or French only) and non-standardisation, especially in relationship with the introduction of English as a corporate language in multinational companies. Some studies remain mainly descriptive (McAll et al. 2001). Others apply a rather critical approach towards the linguistic and social-economic impacts of language standardisation in organisations (see also Section 3.3). They try to question and reveal the often hidden power relations that underlie the implementation of hegemonic linguistic policies and practices (Heller 2003; Duchêne and Piller 2011; Piller and Takahashi 2013). Still others are merely prescriptive. For example, the PIMLICO-Project (European Commission 2011: 4) mentioned above, illustrates best practices for imitation (e.g., language training and cultural briefing schemes, the use of professional interpreters and translators or native-speaker recruitment).

This sub-section has provided an overview of specialist literature on practices. The next two (Sections 2.3 and 2.4) will report on the results of 30 case studies carried out by Austrian researchers under the guidance of Eva Lavric (see Lavric 2008a–c, 2009a–c, 2012a–b; Bäck 2004; Bäck and Lavric 2009; Mrázová 2005 and 2009; Lechner 2010). These will also be compared to other, related studies (e.g., Vandermeeren 1998 and 2005; Charles 2002; Poncini 2003; Leeb 2007; Truchot 2009; Truchot and Huck 2009; Millar, Cifuentes, and Jensen 2012, Lüdi 2012; Bellak 2014). As regards the methods employed, these studies were mainly based on qualitative interviews with a number of people in each company, complemented sometimes by questionnaires (in order to reach a wider range of subjects) or linguistic landscaping (cf. Waldthaler 2014; Stingeder 2015). In certain cases, researchers had resort to participant observation or the language-diary method developed by Bürkli (1999). This consists of noting down, in the course of a whole working day (or more), all interactions in which a certain employee is involved, and the languages and variants s/ he uses for different interlocutors, themes and situations. We will proceed from external to internal communication (the communication of a parent company with its subsidiaries being counted as internal), and finish with a sub-section on policies vs. “bricolage”.

2.3Language choices in external communication – issues of adaptation

External communication, especially in selling – business to customer/client (B2C) – lies at the core of all reflections and preoccupations about language needs, policies and practices in business. The common adage is, of course, that you can easily buy anything in your own language, but to sell you must use the customer’s. This idea supposedly reflects the power imbalance in the buyers’ markets that predominate today, which puts sellers in a weaker position and forces them to adapt linguistically. It is not entirely erroneous, but certainly somewhat simplified.

In practice, things may turn out to be more complex, that is, there seem to be products and businesses that are so successful that they sell quite independently of the language strategy adopted. Such market dominance manifests itself in our case studies in two rather different ways. First, in line with expectations, it may result (at least partly) from a well-planned and constantly-refined distribution/language policy. Second, it may derive from the excellence of the product concerned: as we all know, some products simply sell themselves. The latter case is exemplified by one of our Austrian studies (Feurle 2009), which found that neither language policy nor, for example, the company’s webpage are taken very seriously because there is no perceived need to do so. However, we will leave aside such cases and turn to ‘business as usual’, that is, markets with strong competition where sellers must fight to win the customer’s favour.

Here, one of the main findings of studies such as Bäck (2004) is that the need to address the customer’s language issues is closely linked to the choice of distribution channel. Thus, use of a zero-stage channel, where contact with the customer is direct, will require provision to be made for the necessary language skills within the company’s own staff. If, on the other hand, the chain is extended, either by engaging a sales agent or by establishing a joint venture or subsidiary, the language problem is converted from an external to an internal communication issue, or something very similar. In fact, the linguistic power balance is simply inverted. While companies that deal directly with their customers/clients generally find themselves in the weaker position and are thus forced to adapt linguistically, companies that make use of sales agents, joint ventures or subsidiaries will probably be able to force these to adapt – or at least to fall back on a lingua franca (in general, English). This shows how language issues in business are intrinsically related to the power balance between seller and buyer. Millar, Cifuentes, and Jensen (2012: 82) confirm this finding, describing in Danish companies they study the “outsourcing of language needs (with the exception of English) from the head office to native-speaking affiliates and agents, or to affiliates perceived as having linguistic expertise.” Of course, a large number of companies adopt a combined strategy, creating subsidiaries in the most important markets and working through commercial agents or sales managers in the minor ones. These intermediaries are in general very competent in the languages of the countries they cover.

An alternative to the view that “to sell you must adapt” is the conviction that “nowadays everybody speaks English, English being the universal language in business”.33 This, too, is not completely wrong; under certain circumstances it is indeed possible to be successful with “English only”. Among our case studies, we find two pertinent examples. The first (Zipser 2009) is of a Tyrolean appliances manufacturer, with production sites in Hungary and China, that exports virtually worldwide. Its practice is to set up a subsidiary in every single new market and to require all communication inside the group to be in English and to pass through headquarters. Our second example is a small company producing drinks for children. It has achieved significant export success by cooperating in every foreign market with a local distributor who speaks both English and the local language, and who is in charge of adapting the entire marketing strategy, including the product name, to the local situation.

The success of an English-only strategy is heavily dependent on the use of intermediated distribution channels. Moreover, this strategy is seen to be a fiction as soon as the whole system, for example an entire multinational company, is considered. For the language problem is not really solved; it is simply delegated to subsidiaries or distributors, who must make considerable efforts to provide language competences. Therefore, what constitutes a good solution for external communication can pose serious problems for internal communication. Truchot (2009) reflects critically on this practice, focusing on the power imbalance between headquarters and subsidiaries, and on the inequalities that arise through an English-only internalcommunication policy.

Also relevant here is the study by Millar, Cifuentes, and Jensen (2012) of multinationals operating in Denmark. It investigates, not language needs per se, but the representations of those needs. For it soon becomes patent that nearly all participants share the idea that English is sufficient for all purposes, and attribute communication problems to the often poor English skills of their interlocutors (e.g. in French- and Spanish-speaking countries). In doing so, they ignore the possibility that the real causes lie in their own lack of knowledge of local languages and a failure to perceive their relevance. This result – a typical example of what Vandermeeren (1998) and (2005) would call an unconscious language need – can be explained by the sample of companies chosen, which mainly comprised a number of Danish groups, each with several foreign affiliates. Thus Millar, Cifuentes, and Jensen’s study reveals, not the language policies and practices of multinationals, but the nature of internal communication between head offices and foreign subsidiaries. Interestingly, their sample also included one Danish affiliate of a foreign company, which – not unexpectedly – reported communication problems with its head office.

Having dealt with these real or apparent exceptions, let us now come to our main point: the crucial importance of linguistic adaptation (“speaking the customer’s language”) as a success factor in business. This applies particularly to certain sectors where standardisation (i.e., the adoption of a lingua franca like English) is only a second choice, while “compliance” has an overwhelming importance in commercial relationships (see Section 2.4). As a result, companies must provide in some part of their structure the language competences that are necessary for adapting to their customers’ needs.

This is especially true for service companies, and even more for businesses working in tourism, who usually engage directly with their clients and can hardly outsource language skills. It seems to be in tourism that – unsurprisingly – we find the most versatile code-switchers. Two of our Tyrolean case studies investigate tourist information bureaus (Albel 2009; Reichl 2009), one using a language diary that shows a switching rate of one switch every two or three minutes. The best way for a company to assure good external communication is, of course, to make use of its own personnel, which means recruiting staff with specific language skills (especially native speakers), or providing language training for existing employees (usually during employees’ free time, but financed by the company). We can cite the case of one Tyrolean bank (Handle 2009) that opened a special office for Italian clients only, partly by employing Italian native speakers and partly by funding language courses for its staff. As for Mrázová’s (2005, 2009) investment bank in Paris, it uses a special team of native (or near-native) speakers for every one of its important markets. And the case study of the timber industry in Tyrol (Steiner 2009) – a sector that depends to a very large extent on the Italian market – shows that highly professional companies do not employ just one specialist for the most important foreign language; they systematically ensure that other competent speakers are on hand should the specialist be unavailable.

Like other aspects of a business’s operation, language needs are always subject to cost-benefit considerations with their corresponding trade-offs. Even if it is intuitively obvious that foreign language skills impact positively on business results, considerable problems arise as soon as it comes to measuring their benefits. For these are neither operational nor easily quantified, while the costs involved are concrete and readily quantifiable. In addition, they are incurred in the short term, whereas a good language policy will only bear fruit after a certain period of time. No wonder, then, that – despite fulsome declarations of the need for foreign-language competences – a very simple language investment in a certain market area can fall victim to cuts once its marginal utility is questioned (see Bäck and Lavric 2009: 58). What is more, companies are keenly aware of the changing importance of particular markets, which may lead to recruitment, but also to dismissals as soon as a market seems to lose significance. For example, one of the companies in Bäck’s (2004: 281) study employed an agent for the Russian and Arab markets, but, as sales went down, it hired his services as a freelance instead. Finally, from the individual’s point of view, language competences hardly ever pay off in salary terms, but they may be decisive in being recruited at all.

This rational interplay of supply and demand does not always apply, however, as it can be shown that some companies simply fail to take advantage some language skills already available among their employees. This kind of short-sightedness often occurs with very well integrated immigrants from Eastern Europe, who are seen as having fully assimilated to their host countries (see Mrázová 2005 and 2009). In fact, companies should have a detailed insight into the language skills of their entire workforce because one of the results of our case studies is that language competences to some extent create their own market opportunities. That is, a businessperson with a particular language competence will more easily come upon the idea of conquering the corresponding market(s), especially in small companies, where no overall language strategy can easily be implemented. Here the language skills of the company’s head or – more rarely – of a single employee can be decisive for entering a certain market.34

As we have noted, providing the necessary language skills in-house is often the first and best choice for companies (although not cost-neutral). It is true that, for certain types of documents or situations, it may be more convenient to resort to external translating and interpreting services. However, our case studies show that these are rarely used, and can be problematic because of the need for specialised terminology. Only big companies with a radical adaptation strategy report that they regularly use translation services, in general for web pages, leaflets, contracts and other written documents. This is the case especially for freight forwarders (cf. Klammer 2009; Mäser 2009), who are the absolute champions when it comes to multilingual homepages. But other companies, especially those with highly technological products, complain about the low accuracy level of translations done by professional translation bureaus. They tend to revert to their own personnel and/ or have their translations checked by long-standing customers. Those who do turn to outside translators consistently use the same individuals, who thus build up a certain competence over the years (cf. Graber 2009; Zipser 2009; also Millar, Cifuentes, and Jensen 2012: 83).

Another question is: where (i.e., in which positions) do foreign language competences tend to be found? The answer is that, while sales managers and secretaries generally possess language skills, these are much rarer – and would often be badly needed – among technical staff. Interestingly, it is not always the highest levels in the corporate hierarchy that are most linguistically skilled, a fact that may reflect the dominant role of English in top business negotiations. Instead, competences are found above all among those employees that deal with foreign customers on a day-to-day basis; in a hotel, for example (see Heis 2009), that includes nearly everybody, from the reception desk to the waiters and the tennis coaches. The same is true for a retail bank or an investment bank (see Mrázová 2005 and 2009). In manufacturing and commercial firms, competences are found among sales managers, who often spend a large part of their time travelling from customer to customer (or from subsidiary to subsidiary). They are important also for secretaries and executive staff who deal with foreign customers via email or phone.

One domain where language skills are almost always missing is that of technical assistance. It seems hard to find technicians with adequate competences, although they are urgently required by many companies. However, especially if the product concerned is technically more sophisticated, we find a certain type of linguisticallycompetent engineer who acts as instructor and trouble-shooter. He or she interacts directly with technicians abroad (who themselves often lack language skills), relying on shared technical knowledge and refined specialist terminology. One such trouble-shooter, employed for the Latin American market (see Feurle 2009), affirms that language skills account for 80% of his job and technical skills only 20%. In the company studied by Lechner (2010), technicians sent to Russia communicated with their local colleagues through basic notions of Russian, gestures and drawings; as this did not work fully satisfactorily, the firm hired a translation student – the researcher – as a language expert.

A further aspect of external communication, much less remarked on than dealings with customers/clients, is that of communication with suppliers. Certainly, as we have already pointed out, the language issue is seen as much less relevant in purchasing. But it can be important there too, and the complacent attitude that companies often adopt as soon as they are in the buyer’s position can be a little short-sighted. Thus linguistic competences relevant for alternative suppliers’ markets might open up new possibilities and help to cut costs. This was the case for one of the companies studied by Bäck (2004: 259), which made use of Italian competences in its purchasing department. The point is definitely proven by the Tyrol fruitimporting company (Loretz 2009) whose whole corporate strategy rests on the excellent Spanish competences of its two bosses, which enable them to manage direct contacts with all their important suppliers. Ironically, for sales purposes this company employs its local dialect of German.

To conclude our discussion of how companies can best generate language skills, we want to add an interesting empirical observation. According to our studies, all (successful) managers think that their approach to the language issue is the optimal one. Thus managers who acquired their language competences at university tend to look for those with a similar educational background, while managers who learned a language during a stay in a country where it is spoken prefer staff with comparable experience abroad. And managers who themselves have done very well with English only (cf. Stiebellehner 2009) are convinced that their employees need no further language skills – in some cases, remaining blissfully unaware that their employees report regular use of a wide range of languages.

Finally, one type of situation which must be considered rather apart from the day-to-day language business is that of high-level negotiations, which form a very special kind of communicative setting with its own set of rules. There, the normal economics of language choice (in sociolinguistics: “code choice”) are overruled by a strong need to put both parties involved on an equal footing, which will generally exclude using the mother tongue of either and militate in favour of a lingua franca. Even language-friendly managers, who usually miss no opportunity to practice their other competences, report that they conduct negotiations almost exclusively in English. However, small talk at the beginning or during pauses provides a good opportunity to use a partner’s own language and thus score on the sympathy scale (see, e.g., Bäck 2004: 234, 282). It might be this role of English in top-level negotiations that contributes to the conviction of some top managers that English alone is sufficient in business, and that other language competences are superfluous (see also Truchot 2009).35 That conviction, in turn, will tend to lead them to implement an English-only language policy inside their organisation as well, and it is to such internal communication that we will now turn.

2.4Language choices in internal communication: Policies vs. “bricolage”

To start this sub-section on internal communication in businesses, we want to report on a company studied by Mrázová (2005, 2009) that experiences a conflict between the provision of language competences for external communication and the ease of internal communication. For each of the important language areas it deals with, the international investment bank concerned employs a team of two or three, at least one being a native speaker and the others having near-native competence. So the question arises: which language will be chosen for inter-team communication? As the company is situated in Paris and most employees speak very good French, in general French acts as the workplace lingua franca. However, the members of the Scandinavian team speak very poor French, so that communication with them must be in English. As a result, internal language patterns are complicated significantly by the company’s primary concern to provide linguistically adequate interlocutors for all of its clients.

This is an example of the local language acting as a workplace lingua franca, with only a small niche for the universal lingua franca English. But in general, when it comes to internal communication, the main question in international businesses is whether to go for English-only. According to Truchot (2009), multinational businesses have to make language choices between three types of languages: the language(s) of the country where their sites are located, the language of the country where the parent company is based, and English as a lingua franca. Certainly, we hold that other choices are possible, depending on the location; for example, a Brazilian multinational operating exclusively in South America might well choose Spanish as its lingua franca. Elsewhere in the Western world, however, companies are increasingly introducing English, either as their company language or as a working language in certain predefined situations such as international or board meetings. In fact, an increasing number of (multinational) companies are introducing a one-language policy because they are convinced that this is the simplest communication solution in a world-wide organisation. Language plurality is seen as a drawback, not as an asset.

A number of authors, among them Truchot (2009) and Millar, Cifuentes, and Jensen (2012), view such policies with a critical eye, showing in their case studies that practices may be quite different from official policies. A number of our case studies, too, show that English-only does not work among employees with the same, non-English mother tongue. This truism is worthwhile asserting in view of the large number of multinational companies that have already introduced English as the official language for all internal communication at the expense of the original company language. This is even more likely to happen when mergers and acquisitions are involved, as English is a solution that in general privileges neither of the new partners. For example, in a merger between an Austrian and an Italian bank (Leeb 2007), English was chosen as the language of the newly constituted group, just as in the Nordea case presented by Charles (2002). Such a language policy appears simplistic and is hardly ever followed in practice by employees, who continue to weave their complex but meaningful language-choice patterns, a process referred to in Lavric (2012a) as bricolage (the French term for “do-it-yourself”). In their spontaneous choice of language, speakers follow four main types of motivation (cf. the language-choice factors developed in Lavric 2000, 2001 and Bäck’s 2004 “motivational factors”)36:

–Natural choice: the use of a common native language or of the language for which the product of the competences of both speakers is greatest (cf. Myers-Scotton’s 1983 “unmarked language choice”);

–Language practising: the wish to practise a language one might not otherwise master so well;

–Prestige: the desire to impress through one’s language competences, and its opposite, the fear of losing face by making mistakes;

–Compliance: the selection of the code that speakers believe to be preferred by their interlocutor.

Only in e-mails, or and in written reports and papers, do employees tend to follow the official language policy, as they know that these kinds of texts may be disseminated more widely. Thus the medium may be an important factor in language choice, while in oral communication, it will be the level of formality associated with a situation that decides on the degree to which an official language policy is followed. In fact, the situations and circumstances in which employees are inclined or disinclined to follow such a policy (and the instruments the company might implement in order to impose it) would make a very interesting topic of investigation at the confluence between policies and practices research.

Be that as it may, and official language policies notwithstanding, in internal communication staff will generally tend to use the language of the country in which their workplace is situated (unless there are some members that do not speak this language at all, as in the Mrázová case in Section 2.3). In doing so, they follow the general rules of language choice in communities with different mother tongues and language skills: usually, a language will be chosen that allows all people present to participate in the conversation (cf. Myers-Scotton’s 1990: 98 “Virtuosity Maxim”: “Switch to whatever code is necessary in order to carry on the conversation / accommodate the participation of all speakers present.”). The smaller or more homogeneous the group, the easier this can be done. Actually, in business as in any other linguistic environments, people do indeed tend to choose the most “natural” or “efficient” or “default” language. For example, in the Austrian subsidiary of a French company, the language of everyday conversation will usually be German, the common native language of the majority of employees. But in communication with the French headquarters, those of the staff who speak French will use this language as much as possible, either because it is natural or to practice their French and show compliance (cf. also Lüdi 2012: 147). This means that in dyadic communication, and in all situations other than official meetings37 or suchlike, individual code choices will tend to follow their own rules. And, should all participants share the same mother tongue, that is, of course, the most natural choice which no language policy will ever prevent them from making.

It may even occur that employees fight to keep their “natural” working language in the face of a corporate language policy. For a series of cases where the staff resisted an English-only policy introduced by the management (in France, and in favour of French instead of English) see, for instance, Truchot and Huck (2009: 15) who put forward arguments partly from a trade unionist’s perspective. They cite, for example, the Inter-Union Campaign for the right to work in French in France (Collectif intersyndical pour le droit de travailler en français en France) and emphasise the imbalance of forces between a parent company and its subsidiaries, as well as the inequalities that arise from an English-only policy. They also stress that the better employees know how to communicate, the better the company should operate. Millar, Cifuentes, and Jensen (2012) report a series of cases where an English-only corporate-language policy imposed by the head office had to be softened up or suspended for some of foreign affiliates owing to the poor English skills of staff there. These cases show how policies that fail to take account of the complexity of the language issue can – after a struggle – be overridden by practices, in the interests of good communication and good operation.

The alternative to defining an official language policy – and this is true for both internal and external communication – is to follow a strategy of linguistic bricolage, of laissez-faire and trust in staff’s improvisation skills (see Lavric 2012a). We have seen in Section 2.3 the case of a company (Stiebellehner 2009) whose head believes strongly that English-only is sufficient, while his staff use a wide range of languages depending on the interlocutor and the situation. This is an example of what could be called “employees’ potential for self-governance”. It confirms once more the subversive idea that many aspects of a business may function, not thanks to, but in spite of top-down policies of the management. Sometimes it seems sufficient to hire the right people and let them act as they please without hindering them. Such a strategy of laissez-faire – a bottom-up language policy – may function very well in small and medium sized companies. It might also be worth trying out in large multinationals, although it seems that these tend to need a well-planned language policy that focuses on present and future needs with a view to conquering new markets systematically through careful consideration of distribution channels and well-budgeted language investments.

In any case it might be advisable, even for large multinationals, not to frustrate bricolage practices developed by employees and managers who use tried and trusted means to resolve challenges in new situations with the means to hand. Millar, Cifuentes, and Jensen (2012: 91) speak of “creative tactics of muddling through and making do” that derive from competences and experiences accumulated over years, which management should value because they usually function rather well – indeed, sometimes better than the official policies. In fact, language-policy researchers have already included such bottom-up strategies in their field of investigation. Suffice it to refer to Lüdi’s (2012: 160) observations on multilingual practices in business, or Bellak’s (2014) study of multinational companies in Austria and Denmark provocatively titled: “Can language be managed in international business?”

In the context of bricolage and code choice, we should also mention a very frequent communicative practice observable in interactions between multilingual individuals with (at least partially) corresponding language “repertoires” (on this concept see, e.g., Busch 2012). Here we seldom find exclusive use of a single language, but rather practices of “code switching” (Myers-Scotton 1990; Auer 1998b; Ammon, Mattheier, and Nelde 2004; Lavric 2009c; Stegu 2009). Code switching is defined as “the alternative use of two or more ‘codes’ within one conversational episode” (Auer 1998a: 1); a base language contributes the syntax and most elements, and some lexical or idiomatic elements of one or more other languages are “switched” in. Should the interlocutors switch repeatedly and regularly between two (or more) languages, the practice is referred to as “code mixing” (Muysken 2000); this happens above all where migrant communities are involved. Issues of situationally-conditioned “code choice” arise, for instance, when small talk takes place in language A (e.g., the language of the customer), while more specialised topics are discussed in language B (e.g., English as a lingua franca). This can happen both in internal and in external communication.

3Language policies in business

3.1Definition of concepts and empirical fields

At the beginning of this section, we would like to return to the definition of “policies” (as opposed to “practices”) we gave in the introduction to this chapter. There we suggested that “the more an action or a choice is purposeful, long-term, future-oriented, company-wide, explicit and top-down, the more it is policy; and the more it is non-reflected, ad hoc, individual, implicit, and bottom-up, the more it is practice”. We stated, however, that current language policy research tends not to respect these criteria strictly and to include in “policies” research many aspects traditionally seen as “practices”. That is why we provisionally defined “language policy” as “the plans, motivations and ideologies developed in the language sector, by all actors ranging from state to business, and from management to individual employees”. Now, in this sub-section, we will give a more detailed outline of possible definitions of “language policy”, before stating our own position.

To do this, we will examine the specialist literature with its various approaches. In applied linguistics and, more precisely, in sociolinguistics, we can locate language policy as a field of study for various scholars, each of whom see the concept differently. Depending on historical traditions (Jernudd and Nekvapil 2012) and scope, the focus of the various studies and the definitions of core concepts may vary significantly. The German linguistics tradition usually distinguishes between two notions, the first being a language policy focused on a single language and therefore mainly concerned with the elaboration and establishment of linguistic norms for spoken and written language, such as orthographic standards and issues of lexis (Sprachpolitik). The second notion (Sprachenpolitik) is a policy which regulates the relationship between different languages and groups of speakers within a given territory (e.g., a state or region) or other socio-cultural unit (e.g., a profession, a sub-culture, a company). It attempts to control the actual social use of languages, defines the linguistic rights of speakers and fixes the official status of individual languages, with or without direct reference to others (Ammon 2010: 636, 650). Here, in this paper, we are concerned primarily with Sprachenpolitik, in the sense of a policy designed to influence the use of different languages available in a company/ organisation. (Of course, a focus on Sprachpolitik in business is also possible and relevant: scholars would then study, for example, issues of “correct” discourse or politeness; see Neustupný and Nekvapil 2003: 185.)

Next, following the French sociolinguist Boyer (2010), we can define language policy as the sum of choices, objectives and orientations adopted by states or other institutions in order to cope with linguistically-conflictive situations. Of course, if we look at organisations, we can observe linguistic contact situations which are not necessarily conflictive – at least on the face of it. However, in their work on multilingual workspaces, some sociolinguists too have recently detected imbalances in power and status among employees with different linguistic backgrounds and resources (Duchêne, Moyer, and Roberts 2013). Some of these studies analyse strategically important functions of human-resource management (HRM) – recruitment and selection, performance appraisal, staff development (comprising training, succession planning and carrier management) and rewarding, or compensation (Fombrun, Tichy, and Devanna 1984: 41) – with regard to language policy. When employees’ linguistic competences are taken into account in studies, the focus is often placed only on recruiting instruments or language-training activities (thus partly reflecting business practice) to the neglect of other areas of HR management such as career management, where criteria for promotion could also include language proficiency. Moreover, companies rarely compensate linguistic competences specifically, although they regularly benefit from the linguistic performance of their staff. For example, multilingual employees whose job has no particular linguistic requirements may also be required to work for their company, more or less regularly, as interpreters, even if they are not professionally trained to do so (Spolsky 2009: 59; Meyer et al. 2010; Duchêne 2011; Duchêne and Heller 2012; Piller and Takahashi 2013). Companies which act in this way might be criticized for being exploitative; but others that collect no information about their staff’s language competences are simply short-sighted. Such wilful ignorance not only shows a lack of respect for employees’ diversity and skills, but is also imprudent because it may lead to business opportunities being missed.

Switching now to the Anglophone/Israeli-American tradition, one author impossible to omit is Spolsky, who has worked on language policy and management in various contexts. Spolsky (2004: 5, 2009, 2012: 5) uses language policy as an umbrella term for three inter-related components: language practices in a community; values and beliefs attached to linguistic varieties, which might be assembled to shape ideologies about languages; and language-management or language-planning activities. Although Spolsky himself largely separates these elements for analytic purposes, we favour a more synthetic view of language policies and practices that highlights the interrelatedness of his factors. In the context of language management at the workplace, Spolsky (2009: 53) states: “Management decisions are intended to modify practices and beliefs in the workplace, solving what appear to the participants to be communication problems.” It is noteworthy that only recently has he begun to use the currently fashionable concept of language management.38

In contrast, another school has worked extensively with a very different concept of language management. The group of linguists including, in particular, Jernudd, Neustupný and Nekvapil developed what they finally called “Language Management Theory” (LMT) out of “language planning theory” as early as the 1980s (Jernudd 1983). They broadened the scope of the term language management and constructed a theoretical model around it. We can find comprehensive depictions of LMT in this wider sense in Neustupný and Nekvapil (2003), Jernudd (2009) and Nekvapil (2009). It has come to constitute a well-developed and established theoretical framework that provides the basis for numerous empirical studies in the field (see, for example, the 2015 special issue of the International Journal of the Sociology of Language on “Language Management”). However, it should not be confused with “language management” as used by other authors unless these explicitly cite LMT as very specifically defined by Jernudd, Nekvapil and Neustupný, in which sense it relates to a very broad range of “acts of attention to ‘language problems’” (Neustupný and Nekvapil 2003: 185). These authors distinguish between simple (individual) and organised (institutional) acts of language management. They view “language management [as] aimed at language or communication, in other words, at language as a system as well as at language use”, and are interested not only in language choices, but also, for instance, in the degree of politeness required in a certain (organisational) culture and situation (Nekvapil and Sherman 2015: 6). These scholars thus refer within LMT to both Sprachpolitik and Sprachenpolitik as defined above.

Linking LMT to our understanding of “language policies and practices” (see below), it is equally obvious that LMT scholars also include language practices in their concept of management. Strikingly, though, only lately and infrequently have they addressed questions of linguistic hegemony, of power struggles between different groups of speakers and of their potentially conflicting interests (Neustupný and Nekvapil 2003: 186; Jernudd and Nekvapil 2012: 35; Nekvapil and Sherman 2015). Nekvapil and Sherman (2015) now integrate the distinction between top-down and bottom-up aspects of language policy into their framework. Of course, sociolinguistics has already highlighted the importance of bottom-up considerations in ensuring that language policy goals are achieved (Boyer 2008; Cichon 2012). But, typically, the studies concerned do not assume language policy to be neutral, perfectly rational and plannable by actors belonging to superior levels of political intervention (see Section 3.3. below). Rather, they posit that individual speakers (“employee-speakers” in organisations) may also initiate political activities and influence language practices in different social domains (bottom-up view).

Regardless of the well-elaborated theories in the field, and the now frequently used term language management, we have chosen here to use language policy in order to place a different focus on the topic. All in all, we have the impression that it covers more explicitly the important aspect of unequal power relations in linguistic contact situations, in companies and elsewhere. It also emphasises the interests of employee-speakers in organisations. Moreover, the use of management evokes certain undesirable connotations. Even when it is conceptualised as being strategic and when it allows for adaptation (in dealing with implementation problems), “management” always implies planning and top-down decisions. Besides, it puts the lens on the maximisation of utility, efficiency (through effective communication) and profitability as the main objectives. As we will see below, this approach entails the risk of unseen and detrimental (side-)effects.

In other words, we will foster an understanding of organisations which emphasises the unplanned and bottom-up elements in a chosen strategy (e.g., a strategy that encourages multilingual practices and linguistic diversity in companies).39 We therefore advocate a more comprehensive definition of corporate language policy which allows inclusion of phenomena that may suddenly emerge in the process of implementing a chosen strategy, and that otherwise might be neglected. As opposed to language management, the notion of language policy encourages researchers to look beyond now outdated functionalist theories of management and to shed light on actors’ interests, on the political games played by speakers and groups of employees, and on the socio-cultural values and norms of speech communities. It therefore incorporates elements of organisational culture, micro-politics and social construction processes. Seen from our perspective, planned (and implemented) language management is usually part of an organisation’s explicit language policy, whereas micro-political activities and tactics can be regarded as part of its implicit policy (for the distinction, see Section 3.4). In many cases, implicit language policy has a much greater impact on employees’ (working) lives (e.g., on their social status and economic success) than explicit language policies and management.

Thus we advocate the use in future critical studies of the term language policy (in preference to language management) because it covers more thoroughly certain topics which are receiving increasing attention from interested scholars in linguistics, management studies, political science. These are: power imbalances in organisations; the interests of speakers with different linguistic backgrounds; the linguistic rights of employees; and the (socio)linguistic inclusion or exclusion of groups of speakers within an organisation.

In light of the above, we can now state our definition of language policy for the purposes of this chapter:40 a corporate language policy regulates the use and non-use of languages and linguistic varieties which employees and managers have at their disposal, whether actually or potentially. From the individual’s perspective these include languages learnt at home, heritage languages and (foreign) languages learnt, for instance, at school or university, and other languages and linguistic varieties acquired in professional life (e.g., during a foreign assignment). Switching from the individual to the societal level, we can distinguish competences in languages and linguistic varieties (with different levels of status and prestige) deriving from nativeness, migration, education and professional training, and socialisation. Language policy in business therefore encompasses all measures aimed, explicitly or implicitly, at influencing the language practices of employees and managers, and at stabilising or changing the power relationships between different languages and groups of speakers within a company.

Armed with our definition, we now proceed, in Sections 3.2 to 3.4, to examine various aspects of language policy: policy levels, policies and power, and forms of implicit and explicit language policy. Our analysis is based on discussions in sociolinguistics beyond the organisational context. However, as we will show, these three core elements play important roles there too.

3.2Levels of language policies

Language policy decisions and activities can be located at the levels of the supra-state and the state, as well as at regional, institutional and organisational levels (see Table 1 in Chapter 12 of this volume, as well as Truchot 1994 and Boyer 1997). In the workplace context, to cite Spolsky (2004: 52), “[m]any of the language-management policies come from a higher level”. Thus a state policy on bi- or multilingualism might influence language policies in businesses. At the same time, local adaptations of organisational language policy are very likely to play a role, as when products and services are sold in a foreign market, and customers do not share a common language with the seller. Similar conclusions were reached by the DYLAN project, which sought to discover and “identify the conditions under which Europe’s linguistic diversity can be an asset for the development of knowledge and economy” (DYLAN 2006). Its results showed that corporate language management/ policies and practices are permeated and determined by context factors set at higher levels. A specific regional or state language policy will strongly influence the design of organisational language policy by means of laws and other language-related regulations and decisions. Here, different histories and legal contexts play an important role. For instance, companies that operate in bilingual Wales or the bi-/trilingual Swiss cantons of Bern, Fribourg, Valais and Grisons) are very likely to develop linguistic practices and policies that differ from those of French companies in bi-/trilingual regions such as Brittany or Alsace (Lüdi et al. 2009: 3‒4; Grin, Sfreddo, and Vaillancourt 2010: 123; Barakos 2014).

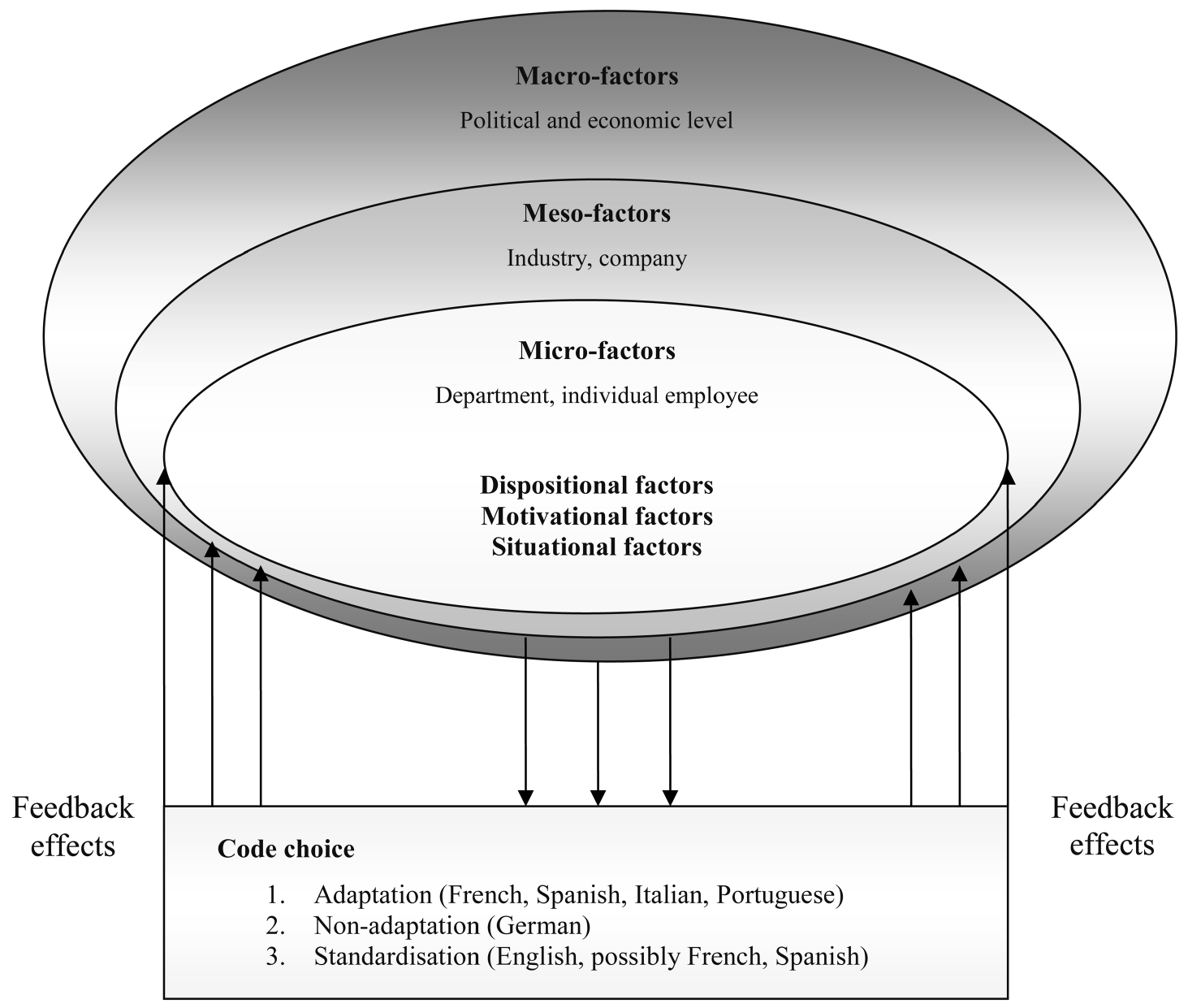

The notion of levels also plays a role in the code choice model developed by Bäck, which is illustrated in Figure 13.3. He applied it in his study of Austrian-based companies exporting mainly to the Romance-speaking world (which explains the examples given of adaptation, non-adaptation and standardisation). The model suggests that language-choice factors operate at three different levels, all of which may influence choices in a specific organisation: a macro-level (e.g., state language policies), a meso-level (e.g., the activities and language policies of a particular sector or company) and a micro-level (e.g., individual employees with their language competences and preferences, the customer involved in the interaction, the specific situation: what Bäck calls “dispositional”, “motivational” and “situational” factors). For example, employees entering an organisation may possess foreign language skills previously acquired in the education system of the country concerned (macro level); they are recruited because they have certain language skills required in the sector in question (meso level); and in each individual situation, they choose their language according to the particular demands, their own preferences and those of their partner(s) (micro level). Bäck’s conceptual framework incorporates interactional and feedback effects between the different levels, and points, like our reflections above, to possible interferences between these. It posits that, provided information about all factors is complete and accurate, future code-choice behaviour should be predictable. As regards the main code-choice strategies, Bäck follows Vandermeeren’s (1998: 21) classification and distinguishes three types: adaptation (use of the customer’s or supplier’s language), non-adaptation (use of one’s own first language) and standardisation (use of a third language, i.e., a lingua franca).

3.3Power relations and language contact

The topic of unequal power distribution resulting from different language competences and membership of linguistically diverse groups of speakers was taken up in distinct disciplines at various times. Thus the conflictual relationship between two or more languages within a given territory deriving from their speakers’ differing status and power resources (diglossic/polyglossic situations) has long been the subject of investigation by sociolinguists (Ferguson 1959; Fishman 1967; Kremnitz 1994: 32, 2004; Hudson 2002). In management studies, by contrast, research interest in the power relations between two or more languages in an organisational context has appeared only during the last decade (Vaara et al. 2005; Tietze and Dick 2013).

However, even in sociolinguistics, the concept of diglossia/polyglossia has as yet been developed and discussed merely at the supra-state, state and regional levels. Here, we will show how it can be transferred to the business context, where many different languages are often present (corporate languages, learned and used foreign languages, heritage languages and first languages). In such situations, we can easily identify (socio)linguistic patterns and functions similar to those pertaining to the higher levels of language policy. Thus in organisations too, linguistic contact situations raise the question of languages’ equally shared or limited functionality for their respective speakers. In most cases, we can expect contact situations in which two or more languages divide linguistic and social functions asymmetrically. For example, in companies where a corporate language is introduced, official internal communication (email, appraisal interviews, meetings, etc.) will switch immediately to it. As a result, local or heritage languages will be used, if at all, only in (informal) day-to-day communication. It is true that this has its importance, for example in terms of identification. However, in official situations there will now be a power gap between native speakers of the new corporate language (often English) and others, which becomes evident in differing career prospects and other areas. In extreme cases, diglossic/polyglossic situations in organisations can lead to language conflict, overt or covert, and induce instability. Heritage languages are especially threatened by such developments; as they cannot be used in everyday working life, they lose functionality for their speakers, whose motivation to use them at all may well be reduced in the long run.

To sum up, and similarly to the situation at state level, diglossic/polyglossic functionalities of languages in organisations may indicate existing imbalances and a power gap between different groups of speakers or employees. The special focus on potentially unequal relationships of different languages in social interactions in the linguistically highly diverse business world (e.g., the hegemonic position of large vehicular languages over other languages) is nowadays addressed not only by sociolinguists, but also by management scholars (Vaara et al. 2005; Tietze and Dick 2013). What these imbalances often imply is a considerable conflict potential, of which decision makers/managers are not always aware. In this regard, we propose to transfer the concept of diglossia/polyglossia to the world of business and to the organisational context. In fact, we see a strong parallel between dominated languages and groups of speakers within a (multinational/international) company and equivalent situations in any other speech community.

In addition, linguists have recently established that, in a globalised world, jobs – especially those in the services sector – can be regarded as scenes where linguistic practices and organisational language policy choices are prone to be maintained, and hence to reproduce certain forms of social inequality. Unequal access to resources in organisations, constraints – more apparent than real – and structures legitimised by powerful actors, may be the result of underlying economic, market-driven, control-based, national or ideological interests. We might therefore ask: Who defines exactly which linguistic competencies are needed in a company and why? Scholars from different disciplines have diagnosed, in selected companies, an increasing hierarchisation of languages and speaker groups, which may have a tangible impact on employees’ psychological condition. In addition, some of these researchers have detected a connection between the degree of linguistic standardisation and the strength of identity in organisations (Heller 2003; Heller and Boutet 2006; Bothorel-Witz and Choremi 2009; Duchêne and Piller 2011; Duchêne, Moyer and Roberts 2013; Piller and Takahashi 2013).

The underlying assumption in these studies is, obviously, that decisions related to organisational language policy (e.g., linguistic standardisation or non-standardisation of corporate communication) affect not only the everyday work of employees, but also their social identity constructions. The link between these latter and policy can be found in the concept of linguistic identity (Kremnitz 1995; Boyer 2008), which implies insights stemming from individual psychology (identity is basically seen as a person’s self-concept) as well as from social psychology (Krappmann 2004; Petzold 2012). For businesses the performance of identities is crucial because processes of identification are closely linked to employee retention and organisational commitment. Additionally, they also have an impact on organisational performance through labour turnover, absenteeism and individual performance (Flynn 2005; Schmidt 2013).

It would seem, then, that managers and employees are largely dependent for their social identity construction on the power relations that characterize their working life, which in turn may be strongly linked to language issues. Such effects may arise not only from language policies in a strict sense, but also from measures intended to act primarily on other areas but which have a strong impact on the relation between language and power.

3.4Implicit and explicit language policy in organisations

In considering the various effects of language-related decisions in companies, an important distinction must be made between implicit and explicit language policies. This dichotomy has been referred to earlier (see Sections 1 and 3.1), but here it will be examined in greater detail. It becomes relevant when, in practice, we are confronted with contradictions between the two types of policies. In order to understand how they arise, we will first examine the two types themselves, starting with the positions that can be found in various branches of the specialised literature.

Of late, implicit and explicit policies have been extensively discussed in combination, both in sociolinguistics (Cichon 2012; Ehrhart 2012; Stegu 2012a) and in international management studies (Peltokorpi and Vaara 2012). It is striking that different scholars have partially divergent views on the distinction between them. This confusion may be due to our everyday understanding of implicitness as something not directly expressed, possibly unclear or even unconscious, such as common prior knowledge that is taken for granted. In contrast, explicitness usually refers to that which is openly and directly communicated, and can be perceived clearly by everyone irrespective of any prior knowledge.

In the realm of language policy, however, the distinction derives from the work of some linguists in the early 1990s and relates to the nature of the goals at which policy is directed. In the case of explicit language policy, these are openly communicated and are concerned with directly influencing the use of languages in various contexts. Explicit language policy can therefore be understood as the sum of measures openly and directly affecting groups of speakers and their use of languages (i.e., language practices). To sum up, the added element in the works concerned (Bochmann 1993: 14; Kremnitz 1994: 80) is the emphasis on goal-orientation of activities undertaken in pursuing language policy. For example, at state or regional level political actors such as (regional) governments, could concede an official status to a previously unofficial and unrecognised language by adapting the legal framework (for instance, the country’s constitution) accordingly, and subsequently enacting detailed legislation to ensure the practical significance of the new status. In the business context, the official introduction of a corporate language is a measure of explicit language policy.

Goal-orientation is also a feature of implicit language policy, but here the underlying mechanism works indirectly rather than directly. In other words, goals are not made explicit. Instead, they are implicit in those of other policy areas (e.g., the economic development of a region, the education of children or adults) that are not necessarily or primarily concerned to influence language practices. Hence implicit language policy may well be the consequence of explicit political and/or organisational measures; its implicitness refers only to the language aspects involved. In practice, it can represent a powerful factor in encouraging the social use of a specific language, as we will see. Thus political actors – governments, non-governmental organisations, the media, employers, unions, economic, and cultural and educational specialists, as well as politicians with responsibilities in the fields of education, culture and the economy, etc. – could undertake measures to raise the social status of (a group of) speakers and their economic well-being. Activities which effectively empower speakers of certain languages in their social and professional life can be classified as operating implicitly on languages (Bochmann 1993: 14; Kremnitz 1994: 80; Cichon 2012: 18).

The same is true of the organisational context, where it is possible to empower certain groups of employee-speakers by promoting the possessors of particular linguistic competences to key positions. The primary purpose of such a promotion, as of any other, is to manage the corporate career system properly, but – as a quasi-side effect – it will upgrade the social status of employees who speak certain languages, and so perhaps also influence certain language practices in the future. Of course, like the explicit variety, implicit language policy – depending on the particular goals pursued – can also be detrimental to certain groups of speakers. Examples arise when multilingual competences are regarded as irrelevant for top management positions, or when quasi-native competences in a newly introduced corporate language are required for promotion.

It is surprising that few linguists (Truchot and Huck 2009; Franceschini 2010: 26; Ehrhart 2012; Stegu 2012a–b) have studied the economic and social success of speakers of particular languages that is emphasised in our definition of implicit language policy, and which plays a very important role in organisations. This lack of research interest is even more astonishing from a management research perspective given that, in companies, implicit language policy in particular is often implemented using human-resource management tools. These might include leadership instruments such as employee appraisals, job interviews, job descriptions and profiles, and criteria used in deciding on compensation and promotion, all of which may, or may not, take linguistic competences and performances into account (see also Section 3.1). Moreover, according to management scholars, the sub-functions of HR management must be coherently aligned with each other, with overall HR strategy and with the strategy of the company as a whole. Such fine tuning calls for comprehensive investigation of the (inter)dependencies involved (Piekkari and Tietze 2012: 552‒559).

Some recent linguistic investigations of the world of work deal with selected HR functions in the context of organisational language policies (European Commission 2006; Libert and Flament-Boistrancourt 2006; Lavric 2008a). Since the functions selected are mostly discussed in isolation from others and from the company’s overall strategy, these analyses make only a limited contribution to developing a comprehensive implicit language policy covering all HR functions systematically. Their main focus is on the use, in recruitment and training, of instruments and strategies which incorporate language-sensitive elements. Further aspects of a global, systematic (implicit) language policy, incorporating other HR development tools, career management measures and instruments of performance management and compensation, are largely ignored. This shows that linguistic approaches to language policies in business alone do not adequately address this quintessentially interdisciplinary topic (see also Section 3.1).

Even if the distinction between implicit and explicit language policies remains useful and widespread, today the two can also be regarded as forming a fluid and dynamic continuum. To illustrate the point, let us consider the language policies of universities which educate students of economics and management studies. Such institutions are generally able to decide, more or less autonomously, whether or not foreign languages play a significant role in their courses of studies. Until recently, this role was usually a crucial one, but in many cases the situation has now changed. Either the number of foreign languages classes has been reduced consciously and explicitly, or other subjects have come to be considered more important and the number of classes offered in them correspondingly increased. The result – sometimes unintended – of this combination of implicit and explicit language policy measures is that foreign languages are now often marginalised in economics and management programmes, or even outsourced by them.

The complexity and interdependency of measures of both types is also evident in other ways. Naturally, some political actors have already recognised the “sideeffects” of an implicit language policy on language use. For instance, providing financial support for economic development in a bilingual territory or a multilingual/ multicultural city district will – hopefully, and at least to some extent – produce positive effects on the income of the local residents, including those who are bi- or multilingual. Then, bi- or multilingual employees would rather stay in the area due to attractive employers and job offers. But if the responsible authority were one day to decide to take economic development measures primarily and expressly in order to maintain and encourage the use of locally-practised languages, the language policy in use will have become more explicit because its main purpose has changed. In general, implicit language policy (regardless of its level) has always existed; it is the explicit variety that is of recent origin and that, even today, does not exist in every context.

At this point, we wish to underline once more that there may be inconsistencies between the elements of a given language policy, between choices about both explicit and implicit language policy measures, and between language practices. Discrepancies and contradictions, where they occur, are often due to underlying, unequal power relations. Thus the mission statement of a company, a university or a political union might state that the organisation is a multilingual one – an example of explicit language policy. However, its job advertisements might ask only for competence in a single foreign-language, in practice usually English (implicit language policy), thereby hindering the employment of new multilinguals. Consequently, multilingual practices at work are likely to disappear more or less slowly. In this example, we would detect contradictions between explicit and implicit language policy, whereas language practices are increasingly aligned with the implicit measures. Also apparent is the power differential between the human-resource manager who determines recruitment policy (effectively “English only”) and the (multilingual) colleagues of new recruits, especially if they have no say in final recruitment decisions.

Other scholars view the distinction between implicit and explicit policy rather differently. Ehrhart (2012: 22‒24) sees the two as somewhat complementary and augments the concepts by adding a time dimension. She distinguishes between short-term, medium-term and long-term perspectives, each of them involving strategic and tactical layers. Moreover, between these two she introduces an eco-linguistic layer incorporating activities that are neither as spontaneous as tactics, nor as reflected and planned as strategies. Comparing Ehrhart’s conceptualisation of language policies and practices to our own, it is noteworthy that her short-term activities correspond largely to our concept of language practices. In our view, the introduction of a temporal dimension into the discussion is definitely helpful and offers further opportunities for analysis.