Urban Public Finance

Edward L. Glaeser, Harvard University and National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, USA

Abstract

America’s local governments spend about one-eighth of our national income, one-fourth of total government spending, and employ over 14 million people. This paper surveys the large and growing economics literature on local governments and their finances. A primary difference between local and national government is the ease of labor mobility within countries, which disciplines local governments and means that heterogeneous service levels can be beneficial, but mobility also challenges local attempts at redistribution. The empirical literature on mobility responses to local government is distinguished, but remains a pressing area for future research. We have sophisticated models of local spending, tax policy, and institutional design, but research is often far less developed on even basic questions of costs and benefits of core local public services.

Keyword

Property taxes; Borrowing; Investments; Centralization; Agglomeration; Cross-state differences; Revenues; Local government; City government; Public finance; Urban politics; Urban infrastructure; City management; Taxation; Mobility

1 Introduction

More than one-half of the world is urbanized and 84% of Americans live in metropolitan areas, which are typically anchored by significant cities. Urban proximity creates abundant externalities—good and bad—and urban governments expanded, long before their rural counterparts, partially to provide the infrastructure that can mitigate adverse urban externalities, like contagious disease. This essay will review the central tasks of local governments and how they are financed, primarily within the United States, with only pay limited attention paid to the rest of the world.

As of 2008, America’s local governments spent about one-eighth of our national gross domestic product (GDP), one-fourth of total government spending, and employ over 14 million people.1 Local governments differ from state and national governments because there are vastly more of them and because they specialize in delivering quite tangible services, like public safety and education, to taxpayers who generally pay for them. In the US, there are three central features that make local government finance distinctly different from public finance at the national or even the state level: property taxes are responsible for the majority of local taxes, intergovernmental transfers provide about one-third of local revenues, and localities typically maintain relatively balanced budgets.

These core features of urban public finance are intimately connected with the nature of cities and the functions of urban governments. One essential feature of cities is that people and capital can readily leave them; greater factor mobility is a key feature of urban, as opposed to national, public finance (Wildasin, 1986), and I review the evidence of migration in Section 6. Indeed, the modern economics literature on local public finance begins with Charles Tiebout’s classic 1956 article, which argued that local governments provided an ingenious way of embedding choice and competition into the provision of public services. The local government dependence on property taxes reflects, in part, the fact that real estate is fixed in a way that labor income is not, which reduces the distortions that can come from mobility. The large role of intergovernmental transfers enables city governments to be tools for redistribution, especially through schooling, despite the fact that the threat of out-migration limits that natural ability to lower levels of government to redistribute.

The discipline that mobility provides on local governments helps explain why these governments are typically far less ideologically partisan than their national equivalents. Ferreira and Gyourko (2009), for example, use a regression discontinuity approach to test whether Democratic or Republican mayors show significantly different spending patterns, as they do at the national or even state levels. Ferreira and Gyourko find little such urban partisanship, which corroborates the apparently similar approaches followed by mayors like New York’s Mayor Bloomberg, who was elected as a Republican, and Chicago’s former Mayor Daley, who was and is a Democrat.

Mobility is one of the forces that create severe limits that constrain the action of urban governments; state laws provide another set of limits. Cities, within the US, are creations of state governments. With the sole exception of Washington, DC, they have no independent constitutional status. As a result, states have generally restricted the taxing, borrowing, and functional authority of local governments, usually by legislative action and occasionally by referendum. Typically, cities like states face at least a notional balanced budget requirement.

Despite the formal limitations that appear to bind city governments, local leaders have often attempted to bypass those limits with different schemes to get around their budget constraints. Compensating workers with underfunded pension and health care benefits may be the most important example of bypassing the budget constraint, but there are many others. Privatizing city assets, such as selling the right to collect parking meter payments over future decades, recently created a cash windfall for Chicago.

There has also been a steady stream of governmental innovations that often create substitutes for traditional local government. There has been phenomenal growth, for example, in the number of special districts which provide services ranging from education to firefighting to public transit (Berry, 2009). America has also seen an explosion in the number of private and often gated communities (Blakely & Snyder, 1999), where corporations essentially take on the core tasks of local governments, and other nations have also followed this trend (Atkinson, Blandy, & Mostowska, 2007). Large cities have increasingly seen Business Improvement Districts (BIDs) where businesses pay fees for increased policing and improvements in public spaces.

The constraints on local government financing become particularly obvious during cyclical downturns, such as the American recession that began in 2007. In response, the federal government has stepped in providing support both for urban infrastructure, like roads, and basic funding of local government services, like schools. Federally managed revenue smoothing over the business cycle may have advantages relative to huge local spending cutbacks during downturns, but relying on federal support may also have costs, especially if the spending goes to services that have limited value, relative to a more locally managed smoothing process.

The American tradition of decentralized political authority is not unique but it does lie at the end of the global spectrum. At the other end are countries, such as the United Kingdom, where the national government maintains far more responsibility over local services. The mayor of London’s power, for example, extends primarily over transportation matters, while the home secretary and the education secretary have greater authority over London’s safety and schools. India occupies a middle ground where large state governments control most urban services.

Within the US, there are cross-state differences in the responsibilities allotted to cities and cross metropolitan area differences in the degree of political fragmentation. In some areas, such as Boston, the central city occupies a very small sliver of the metropolitan area and is surrounded by a vast number of smaller communities. In other metropolitan areas, such as Denver, the central city occupies a much larger spatial footprint. The spatial size of the central city can mean that its government essentially enjoys more monopoly power within the region.

The costs and benefits of decentralization and political fragmentation have been debated by economists since Tiebout. Tiebout’s core followers emphasize the benefits of diversity and competition. Their intellectual opponents argue that smaller areas cannot coordinate sufficiently to provide region-wide public goods or social services (Rusk, 1993). Empirical attempts to uncover the benefits of local government competition (Hoxby, 2000) have often met with serious debate (Rothstein, 2007).

In this essay, I will begin by reviewing the basics of city services, regulatory powers, and finance in Section 2. I will also include some discussion of the history of American city governments and some discussion with government structures in other parts of the world. Every country’s approach to urban government is different, so it would be impossible to meaningfully survey the world’s urban governments, but I will add a bit of international perspective mainly to emphasize the range of political options that are, at least in principle, available.

In Section 3, I will turn to the key features of urban governments: decentralized and limited authority, urban externalities, and selective migration. As I have already argued, these elements of urban government interact in important ways. Moreover, they all must be understood if we are to better understand or even improve urban government.

In Section 4, I will present a model of urban taxation and city services. The model takes the existence of a city as given, and then presents the key conditions for optimal taxation and service delivery. In line with standard urban models, maximizing social welfare (globally) occurs when a locality makes choices that either maximize local population or land value.2 The model delivers the standard result that a land tax is essentially non-distortionary at the local level (although that depends on having no investments that improve the value of land), but that in the absence of a land tax, a modified Ramsey rule holds for taxing property and income. There is also a version of this rule that holds when labor is mobile, where second-best tax formulas change to reflect geographic mobility.

In Section 5, I turn to the provision and financing of core city services, such as policing and education that is motivated by the results of the model. I discuss the ways in which the sources of revenue interact with the nature of service of provision. I will also use this section to discuss intertemporal aspects of city-budgeting.

Section 6 turns to local taxes and redistribution. As the model in Section 4 highlights, redistribution is a particular challenge for local governments because of mobility. Social welfare-related services were historically delivered by cities themselves, but since the New Deal these have been at least typically funded by higher levels of government, even when control over the services remained lodged at the city level. Other core urban services, like education, often have a redistributive component. There are also aspects of redistribution in some local regulations, like rent control and in some local tax systems.

In Section 7, I turn to urban infrastructure. Cities have often built extremely expensive investments such as water and transit systems. These have rarely been financed with direct taxes, but have almost always involved borrowing and occasionally been supported with large transfers from other levels of government. The Transportation Aid Act of 1973, for example, initiated federal financing for local transit systems. User fees or the sale of impacted land can also help finance the investment. I will discuss, briefly, the literature on cost-benefit analysis and infrastructure.

Section 8 addresses urban politics and institutions. Even within the United States, there is substantial heterogeneity in the forms of city government, between weak mayor systems and strong mayor systems, and areas with city managers. There is far more heterogeneity outside the United States. At one time, political machines dominated many larger cities, but they are considerably rarer today. I will discuss the interplay between political forces and city finances and services. Section 9 concludes.

2 The Functions and Powers of City Governments

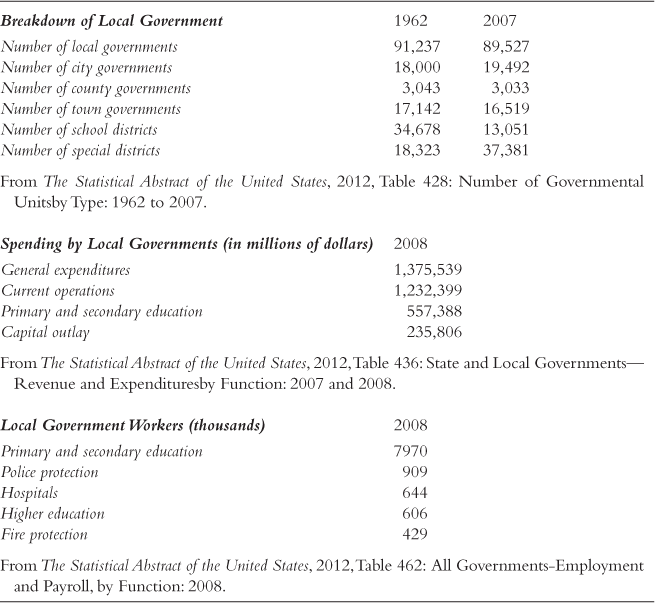

America has a vast number of local governments—more than 89,000 of them—which is quite close to the 91,000 local governments that existed in 1962.3 Of those, 19,492 are city governments, a number that is almost unchanged in 50 years. In 1962, there were 18,000 municipal governments. The number of county governments has stuck between 3033 and 3049 for the last fifty years, and the number of town governments is only slightly more volatile. The number of general-purpose governments in the US is quite static.

By contrast, the number of school and special districts—the other two major types of local governments—has shifted enormously. There were over 34,000 school districts in 1962 and consolidation of far-flung districts means that there are only 13,000 today. The number of special districts has increased from 18,323 to 37,381 in 2007. These districts specialize in natural resources, like water, firefighting, and housing. They typically have a single primary purpose, and are often led by appointed, rather than directly elected, boards.

Taken as a whole, local governments, which include special and school districts, and townships spend 235 billion dollars on capital outlays and $1.2 trillion on current operations. About 40% of local governments spending goes toward primary and secondary education, and more than one-half (7.9 million) of local governments’ workers. The next largest employment area is policing, which employs 909,000, followed by hospitals (644,000), higher education (606,000), and fire protection (429,000). These functions are also significant sources of local government spending, but local utilities are also a large expenditure category, with 168 billion in local government spending nationwide.

There is considerable heterogeneity, however, in the spending patterns of individual large cities, in part because of the functions of government that are taken on by those cities. Taken as a whole, city spending can be grouped into three large bins: basic city services, many of which were meant to address urban externalities (including fire, policing, and waste management); social welfare spending (including explicit social welfare spending, cities hospitals, and housing); and education, which is a service unto itself. The basic services are almost all provided by city governments themselves. Social welfare spending and education are far less ubiquitous.

The overwhelming majority of large cities do not have any spending on education, because that function is overseen by an independent, or quasi-independent, school board. Even in some cases where the mayor maintains a fair amount of control over schooling, such as Chicago, the schools are not an official budget item. Only six of the thirty-five largest cities spend more than 2% of their budgets on education. Likewise, public welfare (which is typically not handled at the city level) involves more than 10% of the budget items for only four of the largest thirty-five cities (New York, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Washington, DC); the majority of large cities spend nothing in this category.

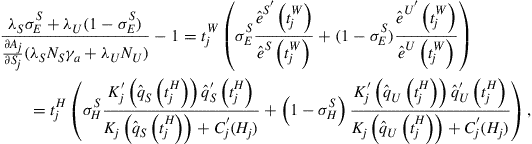

By contrast, every large city has some spending on police, fire, highways, and “parks and recreation.” Almost every city has some spending on “housing and community development,” solid waste management, and sewers, and the overwhelming majority spend on health and hospitals. The different tasks assigned to city governments make it extremely difficult to make sense of total city expenditures of tax levels. Figure 1 shows the relationship between the logarithm city population and per capita expenditure levels in 2000 for cities with more than 200,000 people. The relationship is positive, but at this level, it is hard to know if the relationship represents the greater cost of delivering government services at the city level or just the greater range of services typically provided by city governments, relative to other overlapping jurisdictions.

Figure 1 Population vs. Total Expenditure Per Capita, 2000 (for cities with 200,000 or more people).

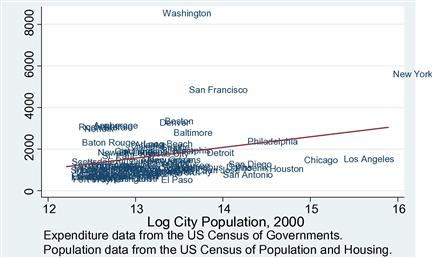

It is somewhat more sensible to discuss differences in spending on particular categories. Figure 2 shows the relationship between per capita spending on police in 2000 and the logarithm of city population for the same sample of larger cities. In this case, the relationship is still potentially troubled by the role that other levels of government often play in policing (e.g., state troopers), but the relationship is closer to have some meaning. Larger cities do typically have higher labor costs and larger crime problems (Glaeser & Sacerdote, 1999) and that combination leads to more police spending.

Figure 2 Population vs. Police Expenditure Per Capita, 2000 (for cities with 200,000 or more people).

On the revenue side, local governments as a whole receive the lion’s share of their revenues from intergovernmental transfers and local property taxes. Out of the $1.5 trillion of total revenues shared by America’s local governments in 2008, $524 billion come from intergovernmental transfers, and $397 billion came from property taxes. Sales taxes produced another $90 billion of revenue, but local governments, taken as a whole, rely very little on income or business taxes. The other two significant sources of revenues are user fees for utilities and hospitals, but these revenues fall significantly below the costs of providing these services.

The dominance of the property tax is among the most salient aspects of local government, and this has been the topic of significant amounts of academic research. Property tax rates differ in nominal rates, typical assessment rates (relative to true market values), and overall effective tax rates. For example, Philadelphia and Indianapolis both have quite high effective tax rates of 2.64% and 2.75%, respectively, but Philadelphia’s nominal tax rate is 8.24% and Indianapolis’ nominal rate is 2.75%. The difference, of course, is that while Indianapolis typically assesses at full market value, Philadelphia typically assess at 30% of market value. New York City has one of the most bizarre systems, and one of the lowest effective tax rates of .62%, which is accomplished with a nominal rate of 16.7% and an average assessment value of 3.7%.

The overall revenue picture for individual large cities can be quite different than the aggregate for local governments. New York City is sui generis. With $70 billion in general revenue, New York City’s government is approximately 10 times larger than the governments of Los Angeles and Chicago. The transfers the city receives from other levels of government, $26 billion, are 20 times larger than the two next largest cities, reflecting the larger range of services, especially education and social welfare, which are performed by the city of New York.

Property taxes provide less than one-fifth of New York City’s revenues, but while that is unusual for local governments as a whole, it is not that unusual for large cities to have less dependence on the property tax, which the model of Section 4 can help explain. Outside of Texas, every one of the 10 largest American cities depends on property tax revenue at less than half the standard 40% level for local governments. The only large cities where property taxes account for anything like that share of revenues are Honolulu (44%), Indianapolis (49%), Boston (40%), and Nashville (37%). Sales taxes are also a significant source of revenues, but general sales taxes are typically less significant than property taxes in all but a few western cities, like Phoenix, Tucson, and Albuquerque. Taxes on utilities, and direct utility revenues, also form a substantial part of big city revenues.

In addition, some cities, like New York and Philadelphia, also have income or wage taxes that generate significant revenues. Typically smaller jurisdictions are not granted the authority to levy these taxes, and many would not want to anyway, given the fears of repelling businesses and wealthier individuals. Indeed, Haughwout, Inman, Craig, and Luce (2004) estimate that the elasticity of earnings in cities with respect to the tax rate is so high that income tax rates quickly become counterproductive for producing revenue.

While there is a great deal of disparity in the revenue sources and spending patterns of local governments, local governments do tend to share a fair amount of authority over the built environment and business formation. The right of localities to regulate structures predates the US constitution. Indeed, Novak (1982) argues that the view of ![]() century America as a laissez-faire nation is mistaken, because there was so much regulation going on at the local level. Fire-related building regulations were common in American history for quite understandable reasons.

century America as a laissez-faire nation is mistaken, because there was so much regulation going on at the local level. Fire-related building regulations were common in American history for quite understandable reasons.

The Progressive Era saw a great spread of local regulations of both businesses and structures. New York City imposed the first citywide zoning plan in 1916, which was focused largely on preserving light by requiring building setbacks. Zoning that restricted uses of land to commercial, residential, and industrial purposes in different parts of the city became widespread (apart from Houston) after the Supreme Court deemed it legitimate in the Euclid Case (hence Euclidean Zoning). Every city, including Houston, engages in some form of control over land use.

While there are a number of studies that claim that local land use restrictions can severely distort property values and urban growth (e.g., Glaeser, Gyourko, & Saks, 2005), it also seems clear that there is a great deal of heterogeneity in the severity of these restrictions across space. Typically, large cities are less restrictive than their suburbs (Gyourko, Saiz, & Summers, 2008). Cities with less restrictive building environments tend, unsurprisingly, to have more housing and population growth (Glaeser & Gyourko, 2009) and lower housing prices. Only recently have some locations begun to directly monetize their permitting power by charging explicit impact fees for new projects.

Urban governments also typically have the power to restrict new business formation, particularly if that business has any health consequences. Restaurants and bars, for example, usually require licenses, although sometimes the authority to issue those licenses is lodged at the state, rather than the local level. Business owners often complain that individual cities are extremely hard to start a business in, but so far there is little cross-city research comparable to the cross-country work on the ease of starting a new enterprise and this is a pressing area for empirical work.

While the economics literature on local public finance has been considerably less developed in Europe than in the United States, there have been a number of fine survey essays highlighting the key features of local public finance in several European countries. For example, Friedrich, Gwiazda, and Nam (2003) discuss the public finance systems in Germany, Switzerland, Poland, and the United Kingdom, and provide comparisons in the share of spending done by local governments across the developed world. Municipal governments in France, for example, spend only 5.5% of GDP, but in Sweden local government spending accounted for 27.5% of GDP, which reflects both the large role of local governments in Sweden and the relatively large size of the Swedish state.

But the size of local government spending often provides a relatively misleading characterization of the overall importance of local governments, because that spending may be significantly constrained by central government. Ebel and Yilmaz (2003) sagely warn of the difficulties of using simple measures to capture the degree of fiscal decentralization. These empirical difficulties make cross-country work on local public finance (see, e.g., Mello, 2000) extremely complicated.

If anything, local public finance becomes even more difficult in the developing world, where institutional arrangements are often even more opaque. Moreover, these political institutions are notably fluid. For example, China has moved from having an extremely high level of political centralization, during the 1970s and earlier, to allowing considerably more local autonomy. Yet it is hard for outsiders to really understand how much freedom of operation actually exists at the local level in the People’s Republic. India, typically, has fairly strong states but quite weak governments within those states.

Latin America has historically had many highly centralized governments, such as Chile (Glaeser & Meyer, 2002), but it also has provided some textbook examples of the problems that can result from fiscal decentralization. Argentina, famously, allowed provincial governments to borrow by issuing obligations that became national government debts (Kruegar, 2002). Brazil’s decentralization has also led to significant amounts of subnational debt and a number of other problems (Dillinger & Webb, 1999).

On one level, the dizzying array of local governmental institutions across the world should make international comparative work on fiscal federalism enormously enlightening. However, there are so many ways in which institutions differ that the international literature on local public finance has been slow to mature. Often the best work (like Dillinger & Webb, 1999) focuses on just two countries, so that the authors can acquire the rich institutional detail that is necessary to say anything useful.

Moreover, it is unlikely that institutions have a homogeneous impact throughout the world. More decentralization is likely to be beneficial in some areas, and less so in others. Certainly, the competence of the federal government, the strength of local social institutions, and the advantages that are likely to accrue from local variety will all play into the benefits of localization and these certainly differ internationally. So, while the theory of urban public finance should hold internationally, it is likely to be most commonly used within particular large countries.

3 The Core Economics of Urban Government

Before turning to the key empirical findings on urban public finance, this section discusses the core economics of cities and their governments. I begin with discussing why cities exist and then turn to the externalities that are so common in dense communities. Those externalities explain why cities governments emerged early. The final subsection discusses local vs. higher control over public functions in cities.

3.1 The Formation of Cities and their Economies

At their core, cities are the absence of space between people and firms. They are defined by their density. They exist because people either want to be close to each other or close to some fixed geographic characteristic that exists in a place, such as a port, a court, or a coal mine.

Historically, urban theory can be roughly split into agglomeration-based theories of cities and everything else. Agglomeration-based theories, which were clearly described in Marshall (1890) and formalized by Krugman (1991) among others, explain the rise of cities with purely endogenous factors, such as the desire to eliminate the costs of transporting goods, people and ideas. As it is costly to ship products over space, firms cluster in one area. The concentration of potential employers in a place provides a form of insurance for workers who can easily find a new job if their employer has an idiosyncratic shock (see, e.g., Diamond & Simon, 1990)—the resulting matching of worker-to-firm enhances overall productivity. Some recent theories have borrowed from Marshall (1890) and Jacobs (1968) and emphasized the role of spatial proximity in facilitating learning and innovation (Duranton & Puga, 2005; Glaeser, 1999).

While these agglomeration theories now dominate the literature, they are not the only theories of urban concentration. Indeed, the simplest theory of urban density is that an area has an exogenous advantage and people come to be close to that advantage. Those urbanists who claim that geography can explain the location of certain cities have often been derided as geographic determinists, but it is not obvious that they were historically wrong. Waterways played an outsized role in determining the growth of American cities, because shipping was so much cheaper over water than by land. In 1900, every large American city was on a waterway, and Bleakley and Lin (2010) finds that the fall lines of rivers still greatly predict urban density today.

Harbors and agglomeration effects are two economic forces that drive city size, but politics also matters. Cities from ancient Rome to modern Kinshasa have been shaped by powerful central governments that have disproportionately favored residents close to the corridors of power. People cluster around kings and courts, especially when those leaders provide either favors or safety. The tendency of a single mega-city (the capital) to dominate a country’s urban form is much stronger in dictatorships than in stable democracies (Ades & Glaeser, 1995) which may reflect the tendency of democratic regimes to check the favoritism shown to the capital city.

Indeed, American political history shows an acute awareness of the potential advantages going to the capital city and repeated attempts to restrain that tendency. For example, many states and the country as a whole located their capitals far away from large, existing urban centers. One reason for that decision was to limit the flow of funds to any existing city. Other British offshoots, but not Great Britain itself, such as Canada and Australia, also chose to locate their capitals away from large cities for similar reasons. In addition, institutions, such as the Senate, explicitly favored less populous areas within the US.

The fact that cities reflect both innate production advantages of a place and agglomeration economies often complicates the task of actually estimating the economic advantages of density. If people move to areas where productivity is innately greater, then regressing productivity on density will yield biased results. The empirical problem is only exacerbated by the fact that more innately able people may sort into higher density locales.

Scholars have attempted to improve on cross-sectional estimates of the density-productivity relationship in three ways. First, they have used historical variables like density or rail networks in the ![]() century (Ciccone & Hall, 1996). This approach is valid only if these instruments are themselves uncorrelated with omitted productivity or individual ability levels, which is of course debated. Agglomeration economists argue that harbors may have mattered in the

century (Ciccone & Hall, 1996). This approach is valid only if these instruments are themselves uncorrelated with omitted productivity or individual ability levels, which is of course debated. Agglomeration economists argue that harbors may have mattered in the ![]() century but are essentially irrelevant today. A similar approach is followed by Rosenthal and Strange (2008) who use geographic variables, such as bedrock, that make it easier or harder to build up as instruments for density and estimate sizable agglomeration effects.

century but are essentially irrelevant today. A similar approach is followed by Rosenthal and Strange (2008) who use geographic variables, such as bedrock, that make it easier or harder to build up as instruments for density and estimate sizable agglomeration effects.

A second approach estimates urban area effects with individual fixed effects looking at the wage changes for migrants (Glaeser & Mare, 2001). These approaches may be able to eliminate some of the impact of omitted individual ability, yet it does little to distinguish between agglomeration economies and omitted area-level productivity variables. Glaeser and Mare do however argue that urban wage pattern for migrants, which shows little immediate wage gain for new migrants but faster wage growth over time, is probably more compatible with a learning-based agglomeration theory than any geographic advantage-based model.

The third approach examines the impact of a seemingly exogenous increase in local employment on the wages and productivity of other works in the city. Greenstone, Hornbeck, and Moretti (2010) use the location decisions of million dollar plants and compare areas that attract these plants with their competitors that just lost. They also estimate sizable agglomeration economies. The natural criticism against this type of work is that winning the plant may not be orthogonal to unobserved area-level characteristics. Kline and Moretti (2011) demonstrate the impact of the Tennessee Valley Authority on manufacturing development and estimate that these effects also suggest significant agglomeration economies. While any one approach is certainly subject to many criticisms, personally, I tend to find the mass of evidence that agglomeration economies exist, taken as a whole, to be fairly compelling, but taking the opposite view is not unreasonable.

Moreover, the selection of people into cities is not obviously a huge confound, at least based on observables, because cities seem to attract a wide variety of residents. In particular, they tend to attract people at both the top and bottom of the human capital distribution (Glaeser, Resseger, & Tobio, 2011). Inequality tends to be higher in denser areas. There has been relatively little written on the attraction that some rich people have for cities. The presumption is that they are there to take advantage of urban agglomeration economies, but it is also quite possible that many of them enjoy the consumption advantages made possible by urban scale, density, and occasionally historic investments (Glaeser, Kolko, & Saiz, 2001). Much more has been written on the urbanization of the poor.

Poverty rates are typically higher inside cities than in suburbs. Glaeser, Kahn, and Rappaport (2008) find a 10% difference in poverty rates in the 2000 Census. Becker (1965) provided one explanation for this tendency. If the income elasticity of demand for land is sufficiently high, then rich people will tend to live where land is cheap outside the urban core and poorer people will live closer to the center. Glaeser et al. (2008) argue that the income elasticity of demand for land is actually pretty modest, and that access to public transit is a dominant force explaining the urbanization of poverty, at least within the United States.

Cities have also traditionally been magnets for immigrants. Public transit may be one reason for the attraction of cities to recent migrants, but there are surely many other factors. Ethnic neighborhoods have traditionally been gateways into a new country. Urban governments have also often been friendlier to immigrants than suburban areas.

These arguments rely on purely economic factors, but social and political forces also help explain the urbanization of poverty. America’s system of local schooling, for example, pulls many wealthier parents outside of cities. If there is any local tendency to want to locate near similar people, this will exacerbate the power of public transportation or the demand for land. No matter what the cause, cities will continue to have to struggle with their tendency to attract poorer people. The massing of poverty in cities can exacerbate the great challenge of urban externalities, which are discussed next.

3.2 Urban Externalities

When people locate near one another, externalities become more severe. Human noise and refuse, accidental fire, and bacteria will inflict more damage on people who are close than people who are distant. Transportation becomes more difficult on crowded city streets. Crime becomes easier when there are more targets. Addressing urban externalities is the core function of city government, and historically the fight against blights like contagious disease and fire have consumed much of the public sector’s energy in cities.

The most important role of urban government is to provide clean water, for if the water supply becomes polluted death occurs on a large scale. Even the recent history of cities is replete with outbreaks of cholera and yellow fever, which are water-related diseases.4 Major cities have typically been built on rivers, for transportation purposes, but those rivers may not provide a clean source of water, at least once the city population also starts using the river as a dumping spot for refuse. At low population levels, wells can then supplement rivers and, indeed, Boston’s location south of the Charles River owes something to the presence of a usable well. But again, if waste is not properly disposed of, wells can also become easily infected. The signal triumph of modern epidemiology occurred when John Snow traced a London cholera epidemic in 1854 to a water pump that was dispensing disease.

In principle, especially in advanced economies, one could imagine the water problem being essentially handled by private providers. Companies can and do sell clean water and many consumers are willing to pay for water that is not infected. Yet there are three principal reasons why private water provision historically failed to eradicate disease: (1) information asymmetries; (2) contagious disease externalities; and (3) large returns to scale in major infrastructure provision. The quality of water has historically been fairly hard to assess and that means that private providers will often have an incentive to provide dodgy water and claim that it is clean.

In some cases, reputational concerns may be enough to guard against this tendency, but the highly imperfect link between bad water provision and disease limits the power of this reputation mechanism in settings where testing is difficult. In addition, individual consumers do not face the right incentives to buy clean water, since they bear only the costs of disease on themselves, not the costs their illness may impose through contagion on the rest of the city. Finally, the vast scale required for investments, like aqueducts, has been beyond the scope of most private investors historically.

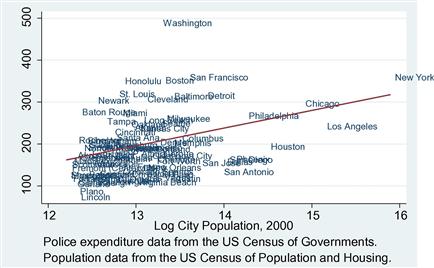

A growing literature is focusing on the impacts of clean water in the US and elsewhere. Troesken and Geddes (2003) have done impressive work showing the health benefits of municipal water provision in early ![]() century cities; African-Americans particularly benefitted from the public provision of water. Ferrie and Troesken (2008) document that Chicago’s investments in water made a significant impact on that city’s mortality transition, causing reduction in a wide range of diseases, even those that are not waterborne. Figure 3 shows the remarkable reductions in mortality within New York City, which have typically been associated with the decline in communicable diseases, many of which are water related. Gamper-Rabindran, Khan, and Timmins (2010) find that piped water significantly reduces infant mortality in modern Brazil.

century cities; African-Americans particularly benefitted from the public provision of water. Ferrie and Troesken (2008) document that Chicago’s investments in water made a significant impact on that city’s mortality transition, causing reduction in a wide range of diseases, even those that are not waterborne. Figure 3 shows the remarkable reductions in mortality within New York City, which have typically been associated with the decline in communicable diseases, many of which are water related. Gamper-Rabindran, Khan, and Timmins (2010) find that piped water significantly reduces infant mortality in modern Brazil.

Figure 3 The Reduction in Mortality in New York City Over Time. (Source: Figure is by courtesy of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (http://cjrc.osu.edu/researchprojects/hvd/usa/nyc/).)

The large expense of water investments creates a close tie between municipal public finance and clean water. Cutler and Miller (2006) argue that widespread water improvements only became possible as American cities got robust access to credit markets in the early ![]() century. They point out that American cities in the early

century. They point out that American cities in the early ![]() century were spending as much on clean water as the federal government was spending on everything except for the post office and the army.

century were spending as much on clean water as the federal government was spending on everything except for the post office and the army.

Cities continue today to be involved with water and sewage by management. Even when these utilities are private, they are highly regulated, both for safety reasons and because they are often seen as natural monopolies. It remains an open question whether private utilities and city governments are spending enough to maintain this infrastructure and certainly some critics allege that they are not.5

While city hospitals are also tools for diminishing the negative externalities associated with disease, their origins lie in charity or redistribution rather than fighting urban externalities. In the ![]() century, wealthier people received their health care (such as it was) at home, while public hospitals, such as New York City’s Bellevue, had their origins as almshouses for the poor. In some cases, city hospitals, such as New York’s Riverside Hospital on what is now called Roosevelt Island, were used to isolate the ill and reduce the spread of contagious diseases like typhoid. Nevertheless, I will address city hospitals at greater length when I turn to the topic of cities and redistribution.

century, wealthier people received their health care (such as it was) at home, while public hospitals, such as New York City’s Bellevue, had their origins as almshouses for the poor. In some cases, city hospitals, such as New York’s Riverside Hospital on what is now called Roosevelt Island, were used to isolate the ill and reduce the spread of contagious diseases like typhoid. Nevertheless, I will address city hospitals at greater length when I turn to the topic of cities and redistribution.

Traffic congestion is another primary urban externality and it has existed far longer than automobiles. The provision of public pathways is a classic form of government. Again, in principle, such roads could be provided privately and some private turnpikes have certainly existed. Yet the fragmented nature of land ownership means that hold-up problems can easily occur, such as the classic case of robber barons that extorted travelers on their roads. Moreover, lightly used, unpaved roads are close to being public goods. They are non-rival, when used lightly, and the cost of charging consumers was high relative to the value of the service.

The public nature of roads meant that cities were closely involved with the private entrepreneurs who initially brought public transportation to cities. America’s first omnibus ran in New York City in the 1820s, and at the point it seemed to be a small business that was naturally a private sector activity. Initially, the earliest transit systems had none of the large scale economies that later helped create local monopolies. No one could advocate for subsidizing public transit to reduce the congestion externalities from driving, since the primarily alternative was walking. The early omnibuses seemed like conventional private sector enterprises, except for the fact that they used publicly owned city streets.

Omnibus operators were soon eager to lay down rails to ease the path of their horse drawn carriages. Later in the ![]() century, private entrepreneurs, like the Wideners in Philadelphia, Jay Gould in New York City, and Charles Yerkes in Chicago, laid more extensive systems over existing public thoroughfares. While these systems were not typically given overt subsidies, transit operators often managed to appropriate formerly public spaces for nominal costs. Allegations of corruption were ubiquitous.

century, private entrepreneurs, like the Wideners in Philadelphia, Jay Gould in New York City, and Charles Yerkes in Chicago, laid more extensive systems over existing public thoroughfares. While these systems were not typically given overt subsidies, transit operators often managed to appropriate formerly public spaces for nominal costs. Allegations of corruption were ubiquitous.

In the ![]() century, these private operations faced tougher fee regulations and lost riders to competing modes of transport. In city after city, transportation became public. Today, public transit systems are typically separate from local government itself, but they still impose significant costs on taxpayers as well as riders. Even the federal government started subsidizing urban transit after the Federal Highway Aid Act of 1973. While these subsidies have been justified as a tool for fighting traffic congestion, Baum-Snow and Kahn (2005) have found that new subway stops typically have had a minimal effect on the share of population commuting by car to work.

century, these private operations faced tougher fee regulations and lost riders to competing modes of transport. In city after city, transportation became public. Today, public transit systems are typically separate from local government itself, but they still impose significant costs on taxpayers as well as riders. Even the federal government started subsidizing urban transit after the Federal Highway Aid Act of 1973. While these subsidies have been justified as a tool for fighting traffic congestion, Baum-Snow and Kahn (2005) have found that new subway stops typically have had a minimal effect on the share of population commuting by car to work.

While the logic of having free public roads for low density communities is easy to see, the practice of free road use can lead to problems as urban densities increase. Since individuals do not internalize the externalities created by their travel on others, the roads can become overused and slow to a crawl. Rotemberg (1985) provides a classic analysis of the economics of traffic jams.

The most typical means of addressing traffic congestion is to build more roads, yet this approach creates a behavioral response that can easily undo the benefits of new construction. Duranton and Turner (2009) empirically investigate the “fundamental law of road congestion,” which says that vehicle miles traveled increase one-for-one with highway miles built. That law suggests that construction on its own is unlikely to eliminate the congestion externality, at least at reasonable levels of construction. Likewise, subsidizing alternative modes of transport is, on theoretical grounds, a highly inefficient means of reducing traffic congestion, and empirically does not seem to solve the problem (Baum-Snow & Kahn, 2005).

Economists since William Vickrey have typically advocated some form of congestion pricing to induce drivers to internalize the costs of these externalities. These schemes can reduce congestion considerably, as seen in Singapore and London. Yet they are often politically unpopular and have met with little success in the United States. New York City’s attempt to introduce a congestion charge was stymied by the state legislature.

Instead, cities have turned to alternative tools such as lanes dedicated to cars with more than one or two commuters. Outside the US, cities have used schemes such as allowing cars with odd license plates to drive on some days and cars with even license plates to drive on other days. Rarely have these plans been seen as significant success stories.

Perhaps the most draconian tool that cities have used against congestion is to limit the physical crowding of the city with building regulations. In the ![]() century, fire was fought, in cities like St. Louis, by regulations that limited the use of wood in construction. During the Progressive Era, it became more common to require ventilation in buildings to prevent the spread of disease. Euclidean zoning, which restricted industrial uses in residential areas, was also meant to improve urban health. Finally, as land use restrictions became stricter, height requirements became tools that were limiting the overall growth and density of the city.

century, fire was fought, in cities like St. Louis, by regulations that limited the use of wood in construction. During the Progressive Era, it became more common to require ventilation in buildings to prevent the spread of disease. Euclidean zoning, which restricted industrial uses in residential areas, was also meant to improve urban health. Finally, as land use restrictions became stricter, height requirements became tools that were limiting the overall growth and density of the city.

The limits on building do seem to have had a significant impact on urban growth and pricing. Glaeser et al. (2005) argue that without these restrictions, the cost of an apartment would be close to the physical cost of building up, since higher construction does not typically require any more land in the absence of land use regulations. They estimate that these restrictions have effectively doubled the cost of a Manhattan apartment, which can be seen as the effective “congestion tax” being imposed on people who want to live in the city. They also argue that this “tax” seems far too high relative to the externalities that might occur in the city.

Building heights also relate to crime, as street crime appears to be higher in lower income neighborhoods with taller buildings (Glaeser & Sacerdote, 2000). Crime is not a classic externality, but it has many of the features of congestion and contagious disease. It imposes costs on people who are not criminals and it is typically more severe in cities (Glaeser & Sacerdote, 1999). The maintenance of rule of law is a central role of government, and this remains a significant function for many cities.

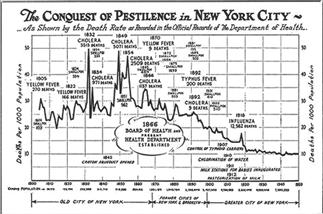

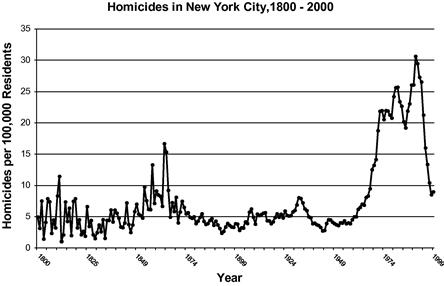

The historian Erik Monkonnen provides us with a long time series of murder rates in New York City, which gives us a sense of the changes in that most serious form of crime over time. Figure 4 shows the long time series of murder rates, which experienced tremendous volatility during the ![]() century. As the police force became professionalized, murder rates declined in the first decades of the

century. As the police force became professionalized, murder rates declined in the first decades of the ![]() century and then soared again after 1960. Cullen and Levitt (1999) estimate the rising crime levels reduce urban growth, and the dangers in our cities may have been one reason for their post-1960 decline.

century and then soared again after 1960. Cullen and Levitt (1999) estimate the rising crime levels reduce urban growth, and the dangers in our cities may have been one reason for their post-1960 decline.

Figure 4 Homicides in New York City, 1800–2000. Data from the Homicide in New York City database, assembled by Erik Monkonnen (http://cjrc.osu.edu/researchprojects/hvd/usa/nyc/).

While the high crime rates of the 1970s made cities seem ungovernable, there have been significant improvements in safety since then. Levitt (2004) looks at the crime decline in the 1990s and argues that increased expenditures on policing and high incarceration rates help explain the drop. It is possible that improvements in policing techniques were also helpful. While the decline in big city crime is hardly the only reason why many cities have experienced comebacks, increased spending on safety did help people to see cities as places of pleasure rather than fear.

3.3 Decentralization and Local Government

While the existence of urban externalities means that cities often need government, it is not necessarily obvious that they need local government. Services could be provided by either state or federal governments, and indeed, in many parts of the world higher levels of government manage many of the affairs of their urban areas. Even within the US, particular city services, like policing, have occasionally been run by state governments. In 1857, for example, New York’s state legislature abolished the municipal police board and was replaced with a state-appointed metropolitan police board, which led to a pitched battle between the two police forces in front of City Hall. Transit systems have been administered by state-appointed officials. In extreme cases, the fiscal distress of particular cities has led to a complete takeover by state-appointed control boards.

Economists have long actively debated the relative merits of decentralized control; Oates (1999) provides a classic summary. Tiebout, most famously, emphasized the benefits of local diversity which enables citizens to vote with their feet and choose the public services that fit their own needs. Alesina, Baqir, and Easterly (2004) find that more racially and financially heterogeneous counties have split into more school districts. Oberholzer-Gee and Strumpf (2002) provide support for Tiebout by documenting that states with more heterogeneity in local preferences have decentralized control over alcohol policy. Besley and Coate (2003) emphasize that this argument presupposes some limit to the benevolence, or competence, of a national government. If a national government had the right incentives and abilities, it could produce the same city services that are currently provided by local governments. It could allow the same spatial heterogeneity that now exists in service levels. This work reminds us that incentives and information are crucial ingredients in any theory of decentralized control.

In reality, it is often quite difficult for the federal government to allow all that much local diversity in its programs. One could plausibly argue that higher density areas need more schooling assistance, while lower density areas need more help with roads. Yet legislative realities mean that transportation and other budget items are handled as a bundle, which means that cities received public transit support in an attempt to create more support for national highway spending. Moreover, it would be extremely difficult to have different federal tax rates for different areas in order to finance the different levels of desired government spending.

Given that city governments grew large before the federal government had a major peacetime role, it is perhaps more reasonable to ask about whether it makes sense to centralize authority given that starting point. Before the rise of the federal government, there seemed to be several attractive elements to America’s decentralized system. There was certainly considerable heterogeneity in the size of government across space, and local taxpayers typically paid for their government themselves. This created a certain pressure to ensure that funded services delivered meaningful benefits.

Highly localized governments may also have been more in touch with their constituents and their interests. Urban machines catered to the poorer citizenry, and especially the needs of recent immigrants. Reform and good-government groups were more likely to be favored by wealthier citizens. In some cases, relatively localized power structures have made it easier for local groups to influence decision-making. The local nature of government also meant that governments themselves often had relatively good information about local conditions. When he was a police commissioner, Theodore Roosevelt would prowl New York City’s streets looking for policemen who were shirking at their jobs.

Despite these seeming advantages, local governments were increasingly seen as inadequate by reformers including abolitionists, populists, progressives, and New Dealers, and there are several arguments that favor centralization. Larger scale governments may attract more talented leaders and enable those leaders to influence a wider range of locations. Boffa, Piolatto, and Ponzetto (2012) present a model where there are decreasing returns to voter information. More informed voters discipline leaders by voting corrupt ones out, as shown in Brazil by Ferraz and Finan (2008), but this has less of an impact as information increases since leaders have fewer rents to forego when they are ousted. If localities have heterogeneous levels of informed voters and the relationship between information and good political behavior is concave, then Jensen’s inequality implies that the level of discipline rises when politicians are elected by larger jurisdictions, since multiple jurisdictions average out local heterogeneity.

Perhaps the most egregious failing of localized authorities is that they are poorly set up to accomplish redistributive goals. If a locality tries to heavily redistribute, then wealthier citizens and businesses have an incentive to flee. In a sense, there is a fiscal externality because the generosity of one jurisdiction attracts beneficiaries from other jurisdictions thereby reducing the fiscal burden on the taxpayers of those other jurisdictions (Wildasin, 1991). More often, the local government just fails to achieve these redistributive aims.

Likewise, in the ![]() century, attempts to redistribute income increasingly involved the national government. The populists wanted redistribution through bimetallism, but during the New Deal, the government embraced a more extensive program of social welfare, which required federal action. One side benefit of this federalization is that an increasingly bureaucratic system involved more paper work and ultimately less corruption (Fishback, 2007). When the welfare state expanded during the war on poverty, federal intervention into local matters, like housing, expanded as well. When Richard Nixon tried to move away from the welfare state, he championed “New Federalism” meant to return power to more local governments. If local governments do not want to attract poorer people, then local control may mean less redistribution, since less generous systems may be one way to repel the poor.6

century, attempts to redistribute income increasingly involved the national government. The populists wanted redistribution through bimetallism, but during the New Deal, the government embraced a more extensive program of social welfare, which required federal action. One side benefit of this federalization is that an increasingly bureaucratic system involved more paper work and ultimately less corruption (Fishback, 2007). When the welfare state expanded during the war on poverty, federal intervention into local matters, like housing, expanded as well. When Richard Nixon tried to move away from the welfare state, he championed “New Federalism” meant to return power to more local governments. If local governments do not want to attract poorer people, then local control may mean less redistribution, since less generous systems may be one way to repel the poor.6

Today, cities are still entwined in a number of social welfare programs that are federally funded but that operate at the local level. Cities typically have housing authorities which interact with the federal government in the operation of housing projects and the administration of Section 8 housing vouchers. Medicaid provides significant funds for city hospitals. These systems are cobbled together to allow local management and federal largesse.

The federal government’s role also expanded because of perceived interjurisdictional externalities often linked to transportation infrastructure. While the Erie Canal was itself an undertaking of New York State, the federal government itself began funding later canals and federal support for such infrastructure projects was a major plank of the Whig party. When the Republicans took over this aspect of Whiggery, the intercontinental railroad system was subsidized with grants of federal land. Starting in the 1920s, and the expanding radically in the 1950s, the federal government began to pay for a national highway system.

While these federal interventions are easy to justify as means of solving coordination problems between jurisdictions, they also remind us that there can be costs of moving expenditures to the federal level. As the gap between a project’s beneficiaries and its funders increase, it becomes increasingly possible to fund very expensive projects that yield relatively little benefit. For example, it is impossible to imagine that Detroit would have funded its People Mover Monorail without federal aid. Given that system’s low ridership levels, non-funding would have surely been the right answer. Transportation projects have only rarely been subject to cost-benefit analysis at the federal level which reinforces suspicions about their wastefulness.

The Interstate Highway System, seemingly the poster child for benevolent federal intervention in infrastructure, has itself been subject to heavy criticism. Many urbanists have argued that highways have badly damaged the cities that they were supposed to serve. Baum-Snow (2007) found that a city’s population declined on average by 18% when two rays of a highway were built into its center. While the decline of urban population is by no means proof of inefficient infrastructure, the Office of Management Budget relates that highway “funding is not based on need or performance and has been heavily earmarked.”7

Between 2009 and 2012, spending on local infrastructure has been tightly tied to moves to reduce recession. For economists who believe in Keynesian anti-recessionary spending, there are good reasons to think that localities will be unlikely to perform the right level of stimulus on their own. If generating extra aggregate demand creates nationwide externalities, these are unlikely to be internalized at the local level.8 This provides one explanation why the federal government’s share of total expenditure soared during the Great Depression and has risen during the recent downturn.

The potential cost of these interventions is that the federal government may not spend in ways that deliver social value at the local level. Again, the Besley and Coate (2003) insight remains—a fully capable and benevolent government would not have such problems. But it is certainly possible that a federal government, facing strong incentives to move money quickly, might spend in ways that are not particularly valuable. The willingness of some states to walk away from proposed federal spending for high speed rail is just one example of a federal project that does not seem well matched to local needs.

The problems of inefficient spending may be mitigated if the federal government acts primarily by giving money to localities and letting them spend as they like. Indeed, recent federal largesse has helped states and cities face budget shortfalls created by the downturn. One potential cost of this approach is that it means that local governments have less incentive to budget for the future.

While it may be easy to laud the benefits of local control, one potential cost of decentralization is that segmentation of the population along race or income. Indeed, Tiebout clearly thought that certain types of segregation, based perhaps on the tastes for public services, were highly desirable. But it is less clear that all forms of segregation are so benign. Cutler and Glaeser (1997) show a strong correlation between the degree of political fragmentation and racial segregation across metropolitan areas and find that African-American outcomes are relatively worse in more segregated areas. For equity reasons, it may also not be desirable to have wealthier children segregated from poor children because of heterogeneity in local school districts. Local control will inevitably mean some degree of sorting and that surely has both benefits and costs. I now turn to a formal model of the financing and provision of core urban services.

4 A Model of Local Government Spending and Finances

I now turn from facts about government finance and spending, and theories about agglomeration economies and negative externalities to a simple benchmark model that nests several of the key results in local public economics. Initially, I assume homogeneous consumers and then extend the model to allow human capital heterogeneity so that I can discuss local redistribution and selective migration across space. In the model, individuals first choose locations and then choose housing quality, effort levels, and an “interactive action” that will impact their neighbors, like driving, which enables me to address local externalities.

Equilibrium in urban models requires three different equilibrium conditions, and the behavior of the local government. Individuals must be indifferent across space or choose to live in one locale only. The costs of supplying housing must equal the price of housing. Finally, the marginal product of labor must equal the wage. I assume that the marginal product of labor per effort unit in the city is fixed at ![]() for workers of type T in city j and hence that will be the wage per unit of effort. For individuals, gross earnings equal

for workers of type T in city j and hence that will be the wage per unit of effort. For individuals, gross earnings equal ![]() , and effort will be chosen by the individual to maximize welfare.

, and effort will be chosen by the individual to maximize welfare.

In the housing market, I gloss over differences between renting and owning and assume, in this static situation, that everyone is an owner, and that everyone occupies one unit of housing, although I allow the housing to have different levels of quality. I let ![]() denote the market price of housing of quality “q” in city j and now turn to the supply decision of developers, whom I assume to be competitive.

denote the market price of housing of quality “q” in city j and now turn to the supply decision of developers, whom I assume to be competitive.

The total supply of housing space in the city equals the total amount of land in the area times the average height on that land. Contrary to the Alonso-Muth-Mills model, I assume all land within the metropolitan area is identical, which is a purely simplifying assumption. There is a fixed amount of land available in the area of ![]() .

.

The total cost of producing a building of height H is ![]() , where H is the height,

, where H is the height, ![]() denotes convex construction costs, L represents the land area bought by the developer, and

denotes convex construction costs, L represents the land area bought by the developer, and ![]() is the equilibrium price of land in city j. The cost of building also increases with unit quality and that is captured with the

is the equilibrium price of land in city j. The cost of building also increases with unit quality and that is captured with the ![]() function; I have assumed that the cost of quality is independent of height. There is also a land tax, that is paid by the developer, and captured by the term

function; I have assumed that the cost of quality is independent of height. There is also a land tax, that is paid by the developer, and captured by the term ![]() .9 I chose to embed quality in the margin to create a clearer difference between a housing tax (which will also impact the quality choice) and a land tax which, given my other assumptions, will not.

.9 I chose to embed quality in the margin to create a clearer difference between a housing tax (which will also impact the quality choice) and a land tax which, given my other assumptions, will not.

The total amount of housing space produced by the developer is HL. Since I have assumed linearity in L, there are no gains from building larger or smaller developments, which is most compatible with the perfect competition assumption. Developers will choose H, L, and q to maximize ![]() , which implies that

, which implies that ![]() , and

, and ![]() . Housing prices will equal the marginal cost of building up and land rents will equal the gap between prices and construction costs. All builders will choose the same height, denoted

. Housing prices will equal the marginal cost of building up and land rents will equal the gap between prices and construction costs. All builders will choose the same height, denoted ![]() . The convexity in the cost for building up is the force that makes the supply of housing slope upward.

. The convexity in the cost for building up is the force that makes the supply of housing slope upward.

In any locality, the government has the ability to impact the quality of life through spending on police or parks or other public services. I assume that the local amenity level is represented by the function ![]() , where

, where ![]() represents aggregate public spending, and

represents aggregate public spending, and ![]() represents the average level of the “interactive action” in the community. This amenity level is assumed to be increasing the level of public spending and decreasing in city size, because of congestion.

represents the average level of the “interactive action” in the community. This amenity level is assumed to be increasing the level of public spending and decreasing in city size, because of congestion.

If there are positive externalities from neighbors, the effect of city size on amenities could also be positive, but I will focus on the downsides of density. The locality is large enough, so that individuals do not internalize the impact of their “interactive action” on the area-level quality of life. The model is somewhat unbalanced, because I allow the possibility of disamenities of city size, which will operate by lowering quality of life, but I exclude the possibility of agglomeration economies, which would cause wages to rise with city size, as they typically do in the real world I made this choice to reduce algebra by allowing only one effect of city size, and I focused on consumption externalities rather than agglomeration economies in production, to tie the model with the externality discussion above and to reduce interactions with the tax on labor income.

The government faces a balanced budget constraint. Revenues come from a tax on labor earnings, ![]() , a tax on housing that is proportional to total housing spending

, a tax on housing that is proportional to total housing spending ![]() , a tax on land

, a tax on land ![]() , and a tax on the interactive action

, and a tax on the interactive action ![]() , which should be understood as essentially a Pigouvian tax. Those revenues will be spent on the public amenity and equal

, which should be understood as essentially a Pigouvian tax. Those revenues will be spent on the public amenity and equal ![]() .

.

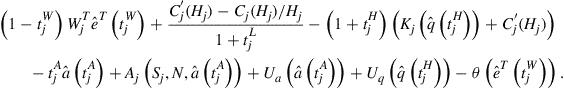

The utility of residents is separable and quasi-linear and equals:

![]() (1)

(1)

where ![]() represents unearned income for type T,

represents unearned income for type T, ![]() and

and ![]() are the welfare from housing quality and the interactive activity (which are strictly concave),

are the welfare from housing quality and the interactive activity (which are strictly concave), ![]() represents the cost of effort (which is strictly convex), and

represents the cost of effort (which is strictly convex), and ![]() represents unearned income from ownership of land. The separability assumption ensures that housing quality will be independent of changes to the land tax or the earnings tax and that effort levels will be independent of the land or housing taxes.

represents unearned income from ownership of land. The separability assumption ensures that housing quality will be independent of changes to the land tax or the earnings tax and that effort levels will be independent of the land or housing taxes.

Three first-order conditions determine the level of effort, housing equality, and amenity-related behavior: ![]() , and

, and ![]() . I denote the optimal effort as

. I denote the optimal effort as ![]() , and the optimal activity level as

, and the optimal activity level as ![]() . By using the developer’s indifference condition, we know that housing quality satisfies

. By using the developer’s indifference condition, we know that housing quality satisfies ![]() , which determines a unique value of housing quality denoted

, which determines a unique value of housing quality denoted ![]() . Differentiation tells us that every endogenous choice is strictly decreasing in the tax related to that choice. If N denotes the total population of the city, then

. Differentiation tells us that every endogenous choice is strictly decreasing in the tax related to that choice. If N denotes the total population of the city, then ![]() , and

, and ![]() .

.

Urban economists have often distinguished between “open city” and “closed city” models, and I will do so here. In closed city models, the population of the city is fixed, which means that the behavior of local governments is typically identical to the behavior of nation-states with the same preferences, tax instruments, and production technology. In open city models, the population adjusts so that welfare in the city equals the reservation utility available elsewhere. The spatial arbitrage condition is crucial in open city models, and absent in closed city models.

In closed city models, Pareto optimality typically involves choosing tax policies to maximize the welfare of residents. In open city models, the welfare of outsiders must also come into normative analysis. Developers compete away any profits in the building industry, so their ownership is irrelevant. I now consider how optimal tax and spending policies differ for closed and open city models, with homogeneous individuals.

In the closed city model I assume that the profits from land sales are shared equally among the residents of the city, so that each resident receives ![]() , which is the gap between marginal cost (which equals price) and average cost. In the closed city model, with homogeneous workers, each person’s welfare is identical

, which is the gap between marginal cost (which equals price) and average cost. In the closed city model, with homogeneous workers, each person’s welfare is identical

(1)

(1)

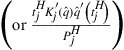

Total spending equals total taxes or ![]()

![]() . This leads to the first result.

. This leads to the first result.

I have specifically omitted formal proofs both to save space and to encourage students to work through the model on their own. When these conditions hold, then the derivative of welfare with respect to the other tax rates is zero, since the benefits of higher taxes (more spending on the public service) are perfectly offset by the cost (less income for private citizens). The second derivative of welfare with respect to all of the taxes is negative, so welfare is maximized when these other taxes are zero.

Claim 1 essentially represents the thinking of Henry George. If a land tax is available, then in a closed city world, then taxing land is the optimal revenue-raising tool since it is non-distortionary. George also thought that the land tax would have desirable redistributive effects, although those are not present here. The result depends on the assumption that no actor has the ability to make investments the increase the market value of land. If developers could build infrastructure that made land more valuable, or even if there were externalities from one development to the value of neighboring land, then a land tax may create distortions.

The amount of the tax should equate the marginal benefit of spending on the public service times the number of people (who all benefit from the spending) with the marginal cost of spending, which here equals 1. Local cost-benefit analysis is essentially about determining whether this equality is satisfied for any particular public project.

The land tax does little to address the externality from social behavior and that is why there needs to be a second tax on that behavior as well. A natural example of the model is urban traffic congestion, where providing an optimal level of road access would require both public spending and a congestion tax. The tax can be negative if the behavior yields a positive spillover.

As the political history of congestion pricing illustrates, political barriers may prevent policies that appear to be desirable. New York City’s attempt to introduce congestion pricing in 2007, for example, was stopped by the closed door session of the Democratic leadership of the New York State Assembly, led by Queens Representative Sheldon Silver. Queens has a significant number of middle-income individuals who drive into Manhattan. Taxing other urban externalities, like contagious disease, faces even more formidable obstacles.

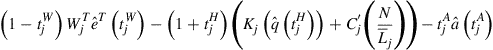

If the tax on socially relevant behavior is unavailable, then there is still no use for earnings or housing taxes in this model, since earnings and housing consumption are independent of the externality creating behavior. The condition for the optimal land tax, and optimal spending, becomes: ![]() . If the behavior is harmful, so that the relevant externality tax generates positive revenues, then an inability to tax the externality will push toward higher land taxes to offset the loss in revenue from the externality-reducing tax. The overall impact on spending also depends on the sign of

. If the behavior is harmful, so that the relevant externality tax generates positive revenues, then an inability to tax the externality will push toward higher land taxes to offset the loss in revenue from the externality-reducing tax. The overall impact on spending also depends on the sign of ![]() , whether spending complements or substitutes for the social behavior.

, whether spending complements or substitutes for the social behavior.

If higher levels of the externality-related behavior increase the returns to spending, then the inability to tax the externality will increase the optimal level of overall public spending. If higher levels of the externality reduce the returns to spending, perhaps pollution makes beaches unusable, then an inability to tax the negative externality will reduce the optimal level of public spending. In the case of roads, the sign of the cross effect is unclear. Higher spending on roads may ease traffic congestion, but it also may mean that extra roads bring less benefit, because they are overused.