We’re in This Together

WHEN MANAGERS FROM WENDY’S International and Tyson Foods sat down together in December 2003 to craft a supply chain partnership, each side arrived at the table with misgivings. There were those on the Wendy’s side who remembered all too well the disagreements they’d had with Tyson in the past. In fact, just a few years earlier, Wendy’s had made a formal decision not to buy from Tyson again. On the Tyson side, some people were wary of a customer whose demands had prevented the business from meeting its profit goals.

A few things had changed in the meantime, or the companies wouldn’t have been at the table at all. First, the menu at Wendy’s had shifted with consumer tastes—chicken had become just as important as beef. The restaurant chain had a large-volume chicken supplier, but it wanted to find yet another. Second, Tyson had acquired leading beef supplier IBP, with which Wendy’s had a strong relationship. IBP’s president and COO, Richard Bond, now held the positions of president and COO of the combined organization, so Wendy’s felt it had someone it could work with at Tyson.

One other thing had changed, too. The companies had a new tool, called the partnership model, to help start the relationship off on the right foot. Developed under the auspices of Ohio State University’s Global Supply Chain Forum, the model incorporated lessons learned from the best partnering experiences of that group’s 15 member companies. It offered a process for aligning expectations and determining the level of cooperation that would be most productive.

With this article, we put that tool in your hands. We’ll explain how, over the course of a day and a half, it illuminates the drivers behind each company’s desire for partnership, allows managers to examine the conditions that facilitate or hamper cooperation, and specifies which activities managers in the two companies must perform, and at what level, to implement the partnership. The model—proven at Wendy’s and in dozens of other partnership efforts—rapidly establishes the mutual understanding and commitment required for success and provides a structure for measuring outcomes.

No Partnership for Its Own Sake

Why do so many partnerships fail to deliver value? Often it’s because they shouldn’t have existed in the first place. Partnerships are costly to implement—they require extra communication, coordination, and risk sharing. They are justified only if they stand to yield substantially better results than the firms could achieve without partnering.

This point was driven home for us early in our research with the Global Supply Chain Forum when its members identified successful partnerships for study. One was an arrangement between a package delivery company and a manufacturer. The delivery company got the revenue it had been promised, and the manufacturer got the cost and service levels that had been stipulated. But it wasn’t a partnership; it was a single-source contract with volume guaranteed. The point is that it’s often possible to get the results you want without a partnership. If that’s the case, don’t create one. Just write a good contract. You simply don’t have enough human resources to form tight relationships with every supplier or customer.

At Wendy’s, managers distinguish between high- and low-value partnership opportunities using a two-by-two matrix with axes labeled “complexity to Wendy’s” and “volume of the buy.” Supplies such as drinking straws might be purchased in huge volumes, but they present no complexities in terms of taste, texture, or safety. Only if both volume and complexity are high—as with key ingredients—does Wendy’s seek a partnership. Colgate-Palmolive similarly plots suppliers on a matrix according to “potential for cost reductions” and “potential for innovation” and explores partnering opportunities with those that rank high in both.

Reserving partnerships for situations where they’re justified is one way to ensure they deliver value. Even then, however, they can fail if partners enter into them with mismatched expectations. Like the word “commitment” in a marriage, “partnership” can be interpreted quite differently by the parties involved—and both sides often are so certain that their interpretations are shared that their assumptions are never articulated or questioned.

What’s needed, then, for supply chain partnerships to succeed is a way of targeting high-potential relationships and aligning expectations around them. This is what the partnership model is designed to do. It is not designed to be a supplier-selection tool. At Wendy’s, for instance, the model was employed only after the company’s senior vice president of supply chain management, Judy Hollis, had reduced the company’s supplier base, consolidating to 225 suppliers. At that point, Wendy’s could say: “Now the decision’s been made. You’re a supplier. Your business isn’t at risk. What we’re trying to do here is structure the relationship so we get the most out of it for the least amount of effort.” That assurance helped people to speak more frankly about their hopes for the partnership—an absolute necessity for the partnership-building process to succeed.

A Forum for Frank Discussion

Under the model, key representatives of two potential partners come together for a day and a half to focus solely on the partnership. Little preparatory work is required of them, but the same can’t be said for the meeting’s organizers (usually staff people from the company that has initiated the process). The organizers face a number of important tasks before the session. First, they must find a suitable location, preferably off-site for both parties. Second, they must engage a session leader. It doesn’t work to have someone who is associated with one of the companies, as we know from the experience of forum members. We recall one session in particular run by Don Jablonski of Masterfoods USA’s purchasing operation. Don is an all-around good guy, is very able at running sessions, and was familiar with the model, but the supplier’s people clammed up and the session went nowhere. They needed an outsider.

Third, the organizers must do some calendar juggling to ensure that the right people attend on both sides. Though there is no magic number of representatives, each team should include a broad mix of managers and individuals with functional expertise. The presence of high-level executives ensures that the work won’t be second-guessed, and middle managers, operations people, and staff personnel from departments such as HR, finance, and marketing can provide valuable perspectives on the companies’ expected day-to-day interactions.

Goals in the Cold Light of Day

After introductions and an overview, the morning of the first day is consumed by the “drivers session,” in which each side’s team considers a potential partnership in terms of “What’s in it for us?” (See the sidebar “How to Commit in 28 Hours.”)

The teams are separated in two rooms, and each is asked to discuss and then list the compelling reasons, from its point of view, for a partnership. It’s vital that participants feel free to speak frankly about whether and how their own company could benefit from such a relationship. What are the potential payoffs? For some teams, there aren’t many. Other teams fill page after page of flip charts.

The partnership drivers fall into four categories—asset and cost efficiencies, customer service enhancements, marketing advantages, and profit growth or stability. The session leader and the provided forms ensure that each of these categories is explicitly addressed. For example, under asset and cost efficiencies, a team might specify desired savings in product costs, distribution, packaging, or information handling. The goal is for the participants to build specific bullet-point descriptions for each driver category with metrics and targets. For the session leader, whose job is to get the teams to articulate measurable goals, this may be the toughest part of the day. It isn’t enough for a team to say that the company is looking for “improved asset utilization” or “product cost savings.” The goals must be specific, such as improving utilization from 80% to 98% or cutting product costs by 7% per year.

Next, the teams use a five-point scale (1 being “no chance” and 5 being “certain”) to rate the likelihood that the partnership will deliver the desired results in each of the four major categories. An extra point is awarded (raising the score to as high as 6) if the result would yield a sustainable competitive advantage by matching or exceeding the industry benchmark in that area. The scores are added (the highest possible score is 24) to produce a total driver score for each side.

This is the point at which the day gets interesting. The teams reassemble in one room and present their drivers and scores to each other. The rules of the game are made clear. If one side doesn’t understand how the other’s goals would be met, it must push for clarification. Failure to challenge a driver implies agreement and obligates the partners to cooperate on it. The drivers listed by a Wendy’s supplier, for instance, included the prospect of doing more business with the Canadian subsidiary of Wendy’s, Tim Hortons. The Wendy’s team rejected the driver, explaining that the subsidiary’s management made decisions autonomously. This is just the sort of expectation that is left unstated in most partnerships and later becomes a source of disappointment.

But expectations are adjusted upward as often as they are lowered. On several occasions, managers reacting to a drivers presentation have been pleasantly surprised to discover a shared goal that hadn’t been raised earlier because both sides had assumed it wouldn’t fly with the other.

The drivers session is invaluable in getting everyone’s motivations onto the table and calibrating the two sides’ expectations. It also offers a legitimate forum for discussing contentious issues or clearing the air on past grievances. During one Wendy’s session, the discussion veered off on a very useful tangent about why the company’s specifications were costly to meet. In another memorable session, we heard a manager on the buying side of a relationship say, “I feel like this is a marriage that’s reached the point where you don’t think I’m as beautiful as I used to be.” His counterpart snapped: “Well, maybe you’re not the woman I married anymore.” The candor of the subsequent discussion allowed the two sides to refocus on what they could gain by working together. As Judy Hollis told us about the Wendy’s-Tyson session, “What they presented to us during the sharing of drivers confirmed that we could have a deeper relationship with them. If we had seen things that were there just to please us, we wouldn’t have been willing to go forward with a deeper relationship.”

The Search for Compatibility

Once the two sides have reached agreement on the business results they hope to achieve, the focus shifts to the organizational environment in which the partnership would function. In a new session, the two sides jointly consider the extent to which they believe certain key factors that we call “facilitators” are in place to support the venture. The four most important are compatibility of corporate cultures, compatibility of management philosophy and techniques, a strong sense of mutuality, and symmetry between the two parties. The group, as a whole, is asked to score—again, on a five-point scale—the facilitators’ perceived strengths. (This implies, of course, that the participants have a history of interaction on which to draw. If the relationship is new, managers will need to spend some time working on joint projects before they can attempt this assessment.)

For culture and for management philosophy and techniques, the point is not to look for sameness. Partners needn’t have identical cultures or management approaches; some differences are benign. Instead, participants are asked to consider differences that are bound to create problems. Does one company’s management push decision making down into the organization while the other’s executives issue orders from on high? Is one side committed to continuous improvement and the other not? Are people compensated in conflicting ways? The session leader must counter the groups’ natural tendency to paint too rosy a picture of how well the organizations would mesh. He or she can accomplish this by asking for an example to illustrate any cultural or management similarity participants may cite. Once the example is on the table, someone in the room will often counter it by saying, “Yeah, but they also do this . . .”

A sense of mutuality—of shared purpose and perspective—is vital. It helps the organizations move beyond a zero-sum mentality and respect the spirit of partnership, even if the earnings of one partner are under pressure. It may extend to a willingness to integrate systems or share certain financial information. Symmetry often means comparable scale, industry position, or brand image. But even if two companies are quite dissimilar in these respects, they might assign themselves a high score on symmetry if they hold equal power over each other’s marketplace success—perhaps because the smaller company supplies a component that is unique, in scarce supply, or critical to the larger company’s competitive advantage.

Beyond these four major facilitators, five others remain to be assessed: shared competitors, physical proximity, potential for exclusivity, prior relationship experience, and shared end users. Each can add one point to the total, for a maximum facilitator score of 25. These factors won’t cripple a partnership if they are absent, but where they are present, they deepen the connection. Think of the extra closeness it must have given the McDonald’s and Coke partnership in the 1990s that both companies loved to hate Pepsi (which at the time owned Kentucky Fried Chicken, Taco Bell, and Pizza Hut franchises, giving it more locations than McDonald’s). Physical proximity certainly adds a dimension to the partnership Wendy’s has with sauce supplier T. Marzetti. With both headquarters in Columbus, Ohio, the two companies’ R&D staffs can collaborate easily. We saw the benefits of proximity, too, in 3M and Target’s partnership. Twin Cities–based managers accustomed to interacting through local charities, arts organizations, and community-building efforts found it easy to collaborate in their work.

Assessing these issues carefully and accurately is worth the sometimes considerable effort, because the scores on facilitators and on drivers in the first session yield a prescription for partnering. The exhibit “The propensity-to-partner matrix” shows how the scores indicate which type of association would be best—a Type I, II, or III partnership or simply an arm’s-length relationship. The types entail varying levels of managerial complexity and resource use. In Type I, the organizations recognize each other as partners and coordinate activities and planning on a limited basis. In Type II, the companies integrate activities involving multiple divisions and functions. In Type III, they share a significant level of integration, with each viewing the other as an extension of itself. Type III partnerships are equivalent, in alliance terminology, to strategic alliances, but we are careful to avoid such value-laden language because there should be no implication that more integration is better than less integration.

The propensity-to-partner matrix

What type of partnership would be best? Once they have measured their desire to partner and determined how easily they could coordinate activities, companies considering working together can use this matrix to decide whether to form a partnership and, if so, at what level.

To put this in perspective, recall that Wendy’s began by consolidating its buying to 225 suppliers. Of these, only the top 40 are being taken through the partnership-model process. And it appears that only a few of the partnerships will end up being Type III. Perhaps 12 or 15 will be Type II, and about 20 will be Type I. This feels like an appropriate distribution. We don’t want participants aspiring to Type III partnerships. We simply want them to fit the type of relationship to the business situation and the organizational environment.

Naturally, the managers in the room do not have to simply accept the prescription. If the outcome surprises them in any way, it may well be time for a reality check. They should ask themselves: “Is it reasonable to commit the resources for this type of partnership, given what we know of our drivers and the facilitators?” If the answer is in doubt, the final session of the process, focusing on the managerial requirements of the partnership, will clarify matters.

Action Items and Time Frames

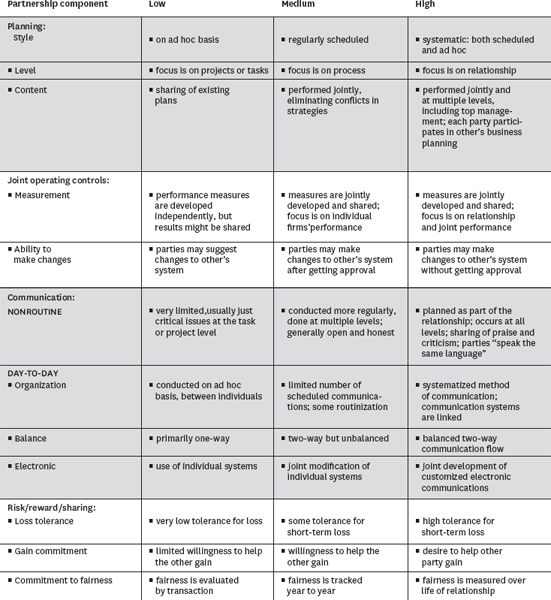

In the third session, the group reconvenes as a whole to focus on management components—the joint activities and processes required to launch and sustain the partnership. While drivers and facilitators determine which type of relationship would be best, management components are the building blocks of partnership. They include capabilities for planning, joint operating controls, communication, and risk/reward sharing. They are universal across firms and across business environments and, unlike drivers and facilitators, are under the direct control of the managers involved.

The two teams jointly develop action plans to put these components in place at a level that is appropriate for the partnership type. Participants are provided with a table of components, listed in order of importance (a portion of such a table is shown in the exhibit “Management components for partnerships”). The first task is for the teams to determine the degree to which the components are already in place. This is a quick process; the participants run through the components in the table, noting whether each type of activity is performed at a high, medium, or low level. Generally speaking, the components should be at a high level for Type III partnerships, a medium level for Type II, and a low level for Type I.

Management components for partnerships*

* In general, Type III partnerships require high levels of most of these components, Type II partnerships require medium levels, and Type I relationships require low levels. (This is just a partial list of managerial components.)

Under the heading of joint operating controls, for example, a Type III partnership would call for developing performance measures jointly and focusing those measures on the companies’ combined performance. A Type II partnership, by contrast, would involve performance measures that focus on each company’s individual performance, regardless of how well the partner performs. In a Type I partnership, the companies would not work together to develop mutually satisfactory performance measures, though they might share their results.

For each management component, the group must outline what, if anything, needs to be done to move from the current state to the capability level required by the partnership. Here, it is helpful to refocus on the drivers agreed to in session one and start developing action plans around each of them. It is in these action plans that the deficiencies of the current management components become apparent. It may be, for instance, that achieving a particular goal depends on systematic joint planning, but the group has just said planning is being performed at a low level. Clearly, planning must be ratcheted up.

One of the needs that became clear in the Tyson-Wendy’s session was for increased communication at the upper levels. People at the operational level in the two companies were communicating regularly and effectively, but there was no parallel for that at the top. Joe Gordon, a commodity manager at Wendy’s, explained why this was a problem: “All of us worker bees sometimes come to a point where we have obstacles in our day-to-day relationship, and in the past we might have given up on trying to overcome them.” After an action plan was outlined for getting the top management teams together to talk, those problems became easier to address.

When the participants leave, they leave with action items, time frames for carrying them out, and a designation of responsible parties. The fact that so much is accomplished in such a brief period is a source of continued motivation. Donnie King, who heads Tyson’s poultry operations, admitted that he had been skeptical going into the meeting. “You tend to believe it is going to be a process where you sit around the campfire and hold hands and sing ‘Kumbaya’ and nothing changes,” he said. But when he left the meeting, he knew there would be change indeed.

A Versatile Tool

The current quality of interaction and cooperation between Tyson Foods and Wendy’s International suggests that the partnership model is effective not only in designing new relationships but also in turning around troubled ones. Today, Wendy’s buys heavily from Tyson and believes the partnership produces value similar to that of the other Wendy’s key-ingredient partnerships. Richard Bond of Tyson told us: “There is a greater level of trust between the two companies. We have had a higher level of involvement in QA regulations and how our plants are audited [by Wendy’s], rather than having [those processes] dictated to us.”

The two companies’ R&D and marketing groups have begun to explore new products that would allow Wendy’s to expand its menu, with Tyson as a key supplier. In a recent interview, we asked the director of supply chain management for Wendy’s, Tony Scherer, to recall the tense conversations of the December 2003 partnership session, and we wondered whether that history still colored the relationship. “No,” he said. “I really do feel like we’ve dropped it now, and we can move on.”

For other companies, the partnership model has paid off in different ways. Colgate-Palmolive used it to help achieve stretch financial goals with key suppliers of innovative products. TaylorMade-adidas Golf Company used it to structure supplier relationships in China. At International Paper, the model helped to align expectations between two divisions that supply each other and have distinct P&Ls. And it served Cargill well when the company wanted several of its divisions, all dealing separately with Masterfoods USA, to present a more unified face to the customer. The session was unwieldy, with seven Cargill groups interacting with three Masterfoods divisions, but the give-and-take yielded a wide range of benefits, from better utilization of a Cargill cocoa plant in Brazil to more effective hedging of commodity price risk at Masterfoods.

But to focus only on these success stories is to miss much of the point of the model. Just as valuable, we would argue, are the sessions in which participants discover that their vision of partnership is not justified by the benefits it can reasonably be expected to yield. In matters of the heart, it may be better to have loved and lost, but in business relationships, it’s far better to have avoided the resource sink and lingering resentments of a failed partnership. Study the relationships that have ended up as disappointments to one party or both, and you will find a common theme: mismatched and unrealistic expectations. Executives in each firm were using the same word, “partnership,” but envisioning different relationships. The partnership model ensures that both parties see the opportunity wholly and only for what it is.

DOUGLAS M. LAMBERT holds the Raymond E. Mason Chair in Transportation and Logistics and A. MICHAEL KNEMEYER is an assistant professor of logistics at the Ohio State University’s Fisher College of Business.

Originally published in December 2004. Reprint R0412H