Rapid-Fire Fulfillment

WHEN A GERMAN WHOLESALER suddenly canceled a big lingerie order in 1975, Amancio Ortega thought his fledgling clothing company might go bankrupt. All his capital was tied up in the order. There were no other buyers. In desperation, he opened a shop near his factory in La Coruña, in the far northwest corner of Spain, and sold the goods himself. He called the shop Zara.

Today, over 650 Zara stores in some 50 countries attract well-heeled customers in luxury shopping districts around the world, and Senor Ortega is arguably the richest man in Spain. The clothing company he founded, called Inditex, has been growing ever since he opened that first Zara shop. From 1991 to 2003, Inditex’s sales—70% of which spring from Zara—grew more than 12-fold from €367 million to €4.6 billion, and net profits ballooned 14-fold from €31 million to €447 million. In May 2001, a particularly tough period for initial public offerings, Inditex sold 25% of its shares to the public for €2.3 billion. While many of its competitors have exhibited poor financial results over the last three years, Zara’s sales and net income have continued to grow at an annual rate of over 20%.

The lesson Ortega learned from his early scare was this: To be successful, “you need to have five fingers touching the factory and five touching the customer.” Translation: Control what happens to your product until the customer buys it. In adhering to this philosophy, Zara has developed a superresponsive supply chain. The company can design, produce, and deliver a new garment and put it on display in its stores worldwide in a mere 15 days. Such a pace is unheard-of in the fashion business, where designers typically spend months planning for the next season. Because Zara can offer a large variety of the latest designs quickly and in limited quantities, it collects 85% of the full ticket price on its retail clothing, while the industry average is 60% to 70%. As a result, it achieves a higher net margin on sales than its competitors; in 2001, for example, when Inditex’s net margin was 10.5%, Benetton’s was only 7%, H&M’s was 9.5%, and Gap’s was near zero.

Zara defies most of the current conventional wisdom about how supply chains should be run. In fact, some of Zara’s practices may seem questionable, if not downright crazy, when taken individually. Unlike so many of its peers in retail clothing that rush to outsource, Zara keeps almost half of its production in-house. Far from pushing its factories to maximize their output, the company intentionally leaves extra capacity. Rather than chase economies of scale, Zara manufactures and distributes products in small batches. Instead of relying on outside partners, the company manages all design, warehousing, distribution, and logistics functions itself. Even many of its day-to-day operational procedures differ from the norm. It holds its retail stores to a rigid timetable for placing orders and receiving stock. It puts price tags on items before they’re shipped, rather than at each store. It leaves large areas empty in its expensive retail shops. And it tolerates, even encourages, occasional stock-outs.

During the last three years, we’ve tried to discover just how Zara designs and manages its rapid-fire supply chain. We conducted a series of interviews with senior managers at Inditex and examined company documents and a wide range of other sources. We were particularly curious to see if Zara had discovered any groundbreaking innovations. We didn’t find any. Instead, we found a self-reinforcing system built on three principles:

- Close the communication loop. Zara’s supply chain is organized to transfer both hard data and anecdotal information quickly and easily from shoppers to designers and production staff. It’s also set up to track materials and products in real time every step of the way, including inventory on display in the stores. The goal is to close the information loop between the end users and the upstream operations of design, procurement, production, and distribution as quickly and directly as possible.

- Stick to a rhythm across the entire chain. At Zara, rapid timing and synchronicity are paramount. To this end, the company indulges in an approach that can best be characterized as “penny foolish, pound wise.” It spends money on anything that helps to increase and enforce the speed and responsiveness of the chain as a whole.

- Leverage your capital assets to increase supply chain flexibility. Zara has made major capital investments in production and distribution facilities and uses them to increase the supply chain’s responsiveness to new and fluctuating demands. It produces complicated products in-house and outsources the simple ones.

It took Zara many years to develop its highly responsive system, but your company need not spend decades bringing its supply chain up to speed. Instead, you can borrow a page from Zara’s playbook. Some of Zara’s practices may be directly applicable only in high-tech or other industries where product life cycles are very short. But Ortega’s simple philosophy of reaping profits through end-to-end control of the supply chain applies to any industry—from paper to aluminum products to medical instruments. Zara shows managers not only how to adjust to quixotic consumer demands but also how to resist management fads and ever-shifting industry practices.

Close the Loop

In Zara stores, customers can always find new products—but they’re in limited supply. There is a sense of tantalizing exclusivity, since only a few items are on display even though stores are spacious (the average size is around 1,000 square meters). A customer thinks, “This green shirt fits me, and there is one on the rack. If I don’t buy it now, I’ll lose my chance.”

Such a retail concept depends on the regular creation and rapid replenishment of small batches of new goods. Zara’s designers create approximately 40,000 new designs annually, from which 10,000 are selected for production. Some of them resemble the latest couture creations. But Zara often beats the high-fashion houses to the market and offers almost the same products, made with less expensive fabric, at much lower prices. Since most garments come in five to six colors and five to seven sizes, Zara’s system has to deal with something in the realm of 300,000 new stock-keeping units (SKUs), on average, every year.

This “fast fashion” system depends on a constant exchange of information throughout every part of Zara’s supply chain—from customers to store managers, from store managers to market specialists and designers, from designers to production staff, from buyers to subcontractors, from warehouse managers to distributors, and so on. Most companies insert layers of bureaucracy that can bog down communication between departments. But Zara’s organization, operational procedures, performance measures, and even its office layouts are all designed to make information transfer easy.

Zara’s single, centralized design and production center is attached to Inditex headquarters in La Coruña. It consists of three spacious halls—one for women’s clothing lines, one for men’s, and one for children’s. Unlike most companies, which try to excise redundant labor to cut costs, Zara makes a point of running three parallel, but operationally distinct, product families. Accordingly, separate design, sales, and procurement and production-planning staffs are dedicated to each clothing line. A store may receive three different calls from La Coruña in one week from a market specialist in each channel; a factory making shirts may deal simultaneously with two Zara managers, one for men’s shirts and another for children’s shirts. Though it’s more expensive to operate three channels, the information flow for each channel is fast, direct, and unencumbered by problems in other channels—making the overall supply chain more responsive.

In each hall, floor to ceiling windows overlooking the Spanish countryside reinforce a sense of cheery informality and openness. Unlike companies that sequester their design staffs, Zara’s cadre of 200 designers sits right in the midst of the production process. Split among the three lines, these mostly twentysomething designers—hired because of their enthusiasm and talent, no prima donnas allowed—work next to the market specialists and procurement and production planners. Large circular tables play host to impromptu meetings. Racks of the latest fashion magazines and catalogs fill the walls. A small prototype shop has been set up in the corner of each hall, which encourages everyone to comment on new garments as they evolve.

The physical and organizational proximity of the three groups increases both the speed and the quality of the design process. Designers can quickly and informally check initial sketches with colleagues. Market specialists, who are in constant touch with store managers (and many of whom have been store managers themselves), provide quick feedback about the look of the new designs (style, color, fabric, and so on) and suggest possible market price points. Procurement and production planners make preliminary, but crucial, estimates of manufacturing costs and available capacity. The cross-functional teams can examine prototypes in the hall, choose a design, and commit resources for its production and introduction in a few hours, if necessary.

Zara is careful about the way it deploys the latest information technology tools to facilitate these informal exchanges. Customized handheld computers support the connection between the retail stores and La Coruña. These PDAs augment regular (often weekly) phone conversations between the store managers and the market specialists assigned to them. Through the PDAs and telephone conversations, stores transmit all kinds of information to La Coruña—such hard data as orders and sales trends and such soft data as customer reactions and the “buzz” around a new style. While any company can use PDAs to communicate, Zara’s flat organization ensures that important conversations don’t fall through the bureaucratic cracks.

Once the team selects a prototype for production, the designers refine colors and textures on a computer-aided design system. If the item is to be made in one of Zara’s factories, they transmit the specs directly to the relevant cutting machines and other systems in that factory. Bar codes track the cut pieces as they are converted into garments through the various steps involved in production (including sewing operations usually done by subcontractors), distribution, and delivery to the stores, where the communication cycle began.

The constant flow of updated data mitigates the so-called bullwhip effect—the tendency of supply chains (and all open-loop information systems) to amplify small disturbances. A small change in retail orders, for example, can result in wide fluctuations in factory orders after it’s transmitted through wholesalers and distributors. In an industry that traditionally allows retailers to change a maximum of 20% of their orders once the season has started, Zara lets them adjust 40% to 50%. In this way, Zara avoids costly overproduction and the subsequent sales and discounting prevalent in the industry.

The relentless introduction of new products in small quantities, ironically, reduces the usual costs associated with running out of any particular item. Indeed, Zara makes a virtue of stock-outs. Empty racks don’t drive customers to other stores because shoppers always have new things to choose from. Being out of stock in one item helps sell another, since people are often happy to snatch what they can. In fact, Zara has an informal policy of moving unsold items after two or three weeks. This can be an expensive practice for a typical store, but since Zara stores receive small shipments and carry little inventory, the risks are small; unsold items account for less than 10% of stock, compared with the industry average of 17% to 20%. Furthermore, new merchandise displayed in limited quantities and the short window of opportunity for purchasing items motivate people to visit Zara’s shops more frequently than they might other stores. Consumers in central London, for example, visit the average store four times annually, but Zara’s customers visit its shops an average of 17 times a year. The high traffic in the stores circumvents the need for advertising: Zara devotes just 0.3% of its sales on ads, far less than the 3% to 4% its rivals spend.

Stick to a Rhythm

Zara relinquishes control over very little in its supply chain—much less than its competitors. It designs and distributes all its products, outsources a smaller portion of its manufacturing than its peers, and owns nearly all its retail shops. Even Benetton, long recognized as a pioneer in tight supply chain management, does not extend its reach as far as Zara does. Most of Benetton’s stores are franchises, and that gives it less sway over retail inventories and limits its direct access to the critical last step in the supply chain—the customers.

This level of control allows Zara to set the pace at which products and information flow. The entire chain moves to a fast but predictable rhythm that resembles Toyota’s “Takt time” for assembly or the “inventory velocity” of Dell’s procurement, production, and distribution system. By carefully timing the whole chain, Zara avoids the usual problem of rushing through one step and waiting to take the next.

The precise rhythm begins in the retail shops. Store managers in Spain and southern Europe place orders twice weekly, by 3:00 PM Wednesday and 6:00 PM Saturday, and the rest of the world places them by 3:00 PM Tuesday and 6:00 PM Friday. These deadlines are strictly enforced: If a store in Barcelona misses the Wednesday deadline, it has to wait until Saturday.

Order fulfillment follows the same strict rhythm. A central warehouse in La Coruña prepares the shipments for every store, usually overnight. Once loaded onto a truck, the boxes and racks are either rushed to a nearby airport or routed directly to the European stores. All trucks and connecting airfreights run on established schedules—like a bus service—to match the retailers’ twice-weekly orders. Shipments reach most European stores in 24 hours, U.S. stores in 48 hours, and Japanese shops in 72 hours, so store managers know exactly when the shipments will come in.

When the trucks arrive at the stores, the rapid rhythm continues. Because all the items have already been prepriced and tagged, and most are shipped hung up on racks, store managers can put them on display the moment they’re delivered, without having to iron them. The need for control at this stage is minimized because the shipments are 98.9% accurate with less than 0.5% shrinkage. Finally, because regular customers know exactly when the new deliveries come, they visit the stores more frequently on those days.

This relentless and transparent rhythm aligns all the players in Zara’s supply chain. It guides daily decisions by managers, whose job is to ensure that nothing hinders the responsiveness of the total system. It reinforces the production of garments in small batches, though larger batches would reduce costs. It validates the company policy of delivering two shipments every week, though less frequent shipment would reduce distribution costs. It justifies transporting products by air and truck, though ships and trains would lower transportation fees. And it provides a rationale for shipping some garments on hangers, though folding them into boxes would reduce the air and truck freight charges.

These counterintuitive practices pay off. Zara has shown that by maintaining a strict rhythm, it can carry less inventory (about 10% of sales, compared to 14% to 15% at Benetton, H&M, and Gap); maintain a higher profit margin on sales; and grow its revenues.

Leverage Your Assets

In a volatile market where product life cycles are short, it’s better to own fewer assets—thus goes the conventional wisdom shared by many senior managers, stock analysts, and management gurus. Zara subverts this logic. It produces roughly half of its products in its own factories. It buys 40% of its fabric from another Inditex firm, Comditel (accounting for almost 90% of Comditel’s total sales), and it purchases its dyestuff from yet another Inditex company. So much vertical integration is clearly out of fashion in the industry; rivals like Gap and H&M, for example, own no production facilities. But Zara’s managers reason that investment in capital assets can actually increase the organization’s overall flexibility. Owning production assets gives Zara a level of control over schedules and capacities that, its senior managers argue, would be impossible to achieve if the company were entirely dependent on outside suppliers, especially ones located on the other side of the world.

The simpler products, like sweaters in classic colors, are outsourced to suppliers in Europe, North Africa, and Asia. But Zara reserves the manufacture of the more-complicated products, like women’s suits in new seasonal colors, for its own factories (18 of which are in La Coruña, two in Barcelona, and one in Lithuania, with a few joint ventures in other countries). When Zara produces a garment in-house, it uses local subcontractors for simple and labor-intensive steps of the production process, like sewing. These are small workshops, each with only a few dozen employees, and Zara is their primary customer.

Zara can ramp up or down production of specific garments quickly and conveniently because it normally operates many of its factories for only a single shift. These highly automated factories can operate extra hours if need be to meet seasonal or unforeseen demands. Specialized by garment type, Zara’s factories use sophisticated just-in-time systems, developed in cooperation with Toyota, that allow the company to customize its processes and exploit innovations. For example, like Benetton, Zara uses “postponement” to gain more speed and flexibility, purchasing more than 50% of its fabrics undyed so that it can react faster to midseason color changes.

All finished products pass through the five-story, 500,000-square-meter distribution center in La Coruña, which ships approximately 2.5 million items per week. There, the allocation of such resources as floor space, layout, and equipment follows the same logic that Zara applies to its factories. Storing and shipping many of its pieces on racks, for instance, requires extra warehouse space and elaborate material-handling equipment. Operating hours follow the weekly rhythm of the orders: In a normal week, this facility functions around the clock for four days but runs for only one or two shifts on the remaining three days. Ordinarily, 800 people fill the orders, each within eight hours. But during peak seasons, the company adds as many as 400 temporary staffers to maintain lead times.

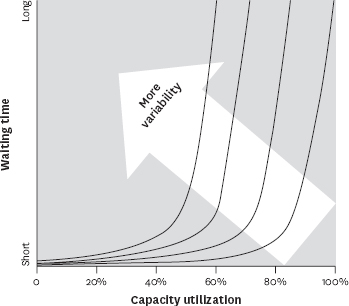

Even though there’s ample capacity in this distribution center during most of the year, Zara opened a new €100 million, 120,000-square-meter logistics center in Zaragoza, northeast of Madrid, in October 2003. Why is Zara so generous with capacity? Zara’s senior managers follow a fundamental rule of queuing models, which holds that waiting time shoots up exponentially when capacity is tight and demand is variable (see the exhibit “For fast response, have extra capacity on hand”). By tolerating lower capacity utilization in its factories and distribution centers, Zara can react to peak or unexpected demands faster than its rivals.

For fast response, have extra capacity on hand

Zara’s senior managers seem to comprehend intuitively the nonlinear relationship between capacity utilization, demand variability, and responsiveness. This relationship is well demonstrated by “queuing theory”—which explains that as capacity utilization begins to increase from low levels, waiting times increase gradually. But at some point, as the system uses more of the available capacity, waiting times accelerate rapidly. As demand becomes ever more variable, this acceleration starts at lower and lower levels of capacity utilization.

Surprisingly, these practices don’t burn up investment dollars. Thanks to the responsiveness of its factories and distribution centers, Zara has dramatically reduced its need for working capital. Because the company can sell its products just a few days after they’re made, it can operate with negative working capital. The cash thus freed up helps offset the investment in extra capacity.

Reinforcing Principles

None of the three principles outlined above—closing the communication loop, sticking to a rhythm, and leveraging your assets—is particularly new or radical. Each one alone could improve the responsiveness of any company’s supply chain. But together, they create a powerful force because they reinforce one another. When a company is organized for direct, quick, and rich communications among those who manage its supply chain, it’s easier to set a steady rhythm. Conversely, a strict schedule for moving information and goods through the supply chain makes it easier for operators at different steps to communicate with one another. And when the company focuses its own capital assets on responsiveness, it becomes simpler to maintain this rhythm. These principles, devotedly applied over many years, help to put together the jigsaw puzzle of Zara’s practices.

Perhaps the deepest secret of Zara’s success is its ability to sustain an environment that optimizes the entire supply chain rather than each step. Grasping the full implication of this approach is a big challenge. Few managers can imagine sending a half-empty truck across Europe, paying for airfreight twice a week to ship coats on hangers to Japan, or running factories for only one shift. But this is exactly why Zara’s senior managers deserve credit. They have stayed the course and resisted setting performance measures that would make their operating managers focus on local efficiency at the expense of global responsiveness. They have hardwired into the organization the lesson Ortega learned almost 30 years ago: Touch the factories and customers with two hands. Do everything possible to let one hand help the other. And whatever you do, don’t take your eyes off the product until it’s sold.

KASRA FERDOWS is the Heisley Family Professor of Global Manufacturing at Georgetown University in Washington, DC. MICHAEL A. LEWIS is a professor of operations and supply management at the University of Bath School of Management in the UK. JOSE A.D. MACHUCA is a professor of operations management at the University of Seville in Spain.

Originally published in November 2004. Reprint R0411G