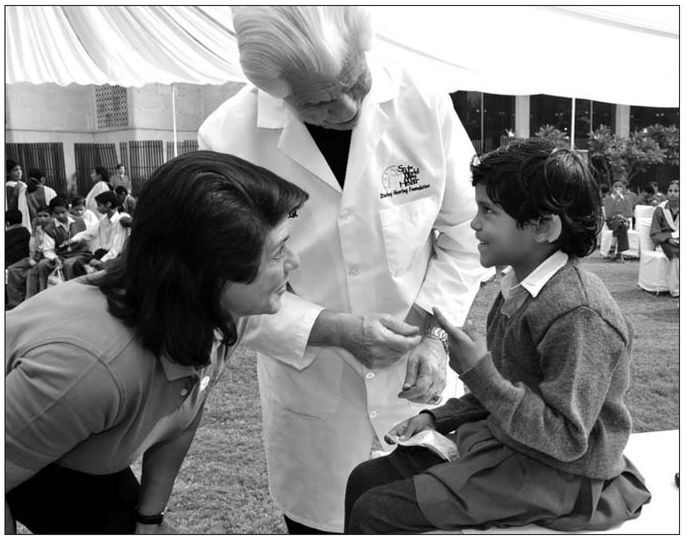

Bill Austin, on a mission in Victoria, Mexico, goes face to face with a small child who just received hearing aids provided by Starkey Laboratories.

So the World May Hear

Starting in his basement in 1967, William ”Bill” Austin opened a small hearing aid clinic and repair shop that later became Starkey Laboratories. Starkey is America’s largest hearing aid company and is the world’s leading manufacturer of custom hearing instruments. Starkey, a privately owned company, is headquartered in Eden Prairie, Minnesota, and Austin serves as its chief executive officer. The company employs 3,700 people in twenty-six facilities around the globe. Starkey has annual revenues in excess of $700 million and conducts business in more than one hundred markets worldwide.

An industry innovator and leader, Bill Austin is hailed as the most admired American in the hearing aid field. His proudest accomplishment is the Starkey Hearing Foundation, a nonprofit organization he founded in 1984 that is dedicated to providing the gift of hearing to those who can least afford a hearing aid. Starkey missions are conducted each year that provide more than 100,000 hearing aids to needy people, mainly children. Accompanied by a team of Starkey employees and often his wife, Tani, Bill personally spends more than four months each year on missions visiting the underprivileged in countries such as India, Vietnam, the Dominican Republic, and South Africa. During these missions, Bill works side by side with his fellow missionaries fitting people with hearing aids. In addition to the costs for administrative, travel, and payroll expenses, the Starkey Foundation gives away more than $50 million (retail value) of hearing aids annually.

Oh you men who think or say that I am malevolent, stubborn, or misanthropic, how greatly do you wrong me. You do not know the secret cause which makes me seem that way to you. For six years now I have been hopelessly affected by the said experience of my bad hearing. Ah, how could I possibly admit an infirmity in the one sense which ought to be more perfect in me than others, a sense which I once possessed in the highest perfection, a perfection such as few in my profession enjoy or ever have enjoyed. Oh I cannot do it; therefore forgive me when you see me draw back when I would have gladly mingled with you. My misfortune is doubly painful to me because I am bound to the misunderstood; for me there can be no relaxation with my fellow men, no refined conversations, no mutual exchange of ideas. I must live almost alone, like one who has been banished; I can mix with society only as much as true necessity demands. If I approach near to people a hot terror seizes me, and I fear being exposed to the danger that my condition might be noticed.

—LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN, October 6, 1802

HUMBLE BEGINNINGS

Born in Nixa, Missouri, on February 25, 1942, Bill was the only child of J. E. “Dutch” and Zola Austin. His paternal grandfather was a sharecropper in Alabama and raised thirteen children. Dutch quit school after the third grade to help his father plow cotton. He migrated north to Missouri during the Depression. Dutch found work on a small farm, and he married Zola, the farmer’s daughter. Dutch was classified 4-F by the military because of his poor vision and flat feet and was unable to enlist during World War II. To help with the war effort, he worked in a munitions plant. Zola worked at the same plant, loading shells.

Bill talks about his early years:

“For the first five years of my life, I was mainly raised by my grandparents. My grandmother was a wonderful woman who had a strong influence on my life. She talked to me as if I were an adult. A religious woman, she took me to church with her on Sundays. She

always had a wise saying to apply to what she wanted to teach me, and hearing them when I was so young left a strong impression on me. One in particular that she drummed into it me was that the idle mind is the devil’s playground.

“Products of the Depression, my parents and grandparents constantly worried about money. It was something that stayed with them all their lives.”73

Zola had a brother, Paul, in Oregon who claimed there were lots of jobs to be had out West. When Bill Austin was five years old, his family moved to Oregon. He says, “My father got a job as a lumber grader with Georgia-Pacific. Later he started his own bartering business collecting and reselling. To make ends meet, my mother and I picked up beer and soda bottles on the roadside. We’d pick them up, put them in our gunny sacks, and when they were filled, we’d get a couple of pennies per bottle for our labor. In the summer, we picked wild blackberries in the fields. I remember how my arms and legs would get scratched up. It was no big deal. It was just part of the job. In the winter, we cut bark from Chittum trees in the forest that we would peal and dry. Then we sold the bark, which was used to make medicinal products. When I was seven, I was old enough to get a paper route.

“I saved my money in a big piggy bank that my uncle gave me. One day I came home from school and discovered that my father had raided it. All my money was gone. He used the money to make a down payment on a house in Bay City, Oregon. I never saw that money again, and he made no attempt to pay it back to me. I know my father never thought that he had done anything wrong. Even as a young child, I understood his motive, and I didn’t dwell on it. Money was not important to me back then, nor has it ever been. Knowing how it meant a lot to my father, there were times when I went to school without money for lunch, and when my father would ask, ‘Do you need lunch money?’ I’d tell him, ‘No. I’m okay.’”74

Dutch’s frugalness was ingrained in him during the Great Depression. For most of his life, Dutch had been dirt poor. He knew the value of a dollar and wanted to make sure his son did, too.

Dutch worked hard in his trading business and built a good reputation for being an honest man. He repeatedly told his young son: “Your word is your bond. If you say something, that’s it! That’s the way it has to be. If you make a mistake, it doesn’t matter if you lose money. That’s irrelevant. You must always keep your word.”75 This advice made a lasting impression on the young lad. Above all else, everyone who knows him will say that Bill Austin always honors his word.

Over time, his father made enough money to buy a fifty-two-acre farm near Salem, Oregon. With no freeways back then, it took several hours to get there from the Austin house. It was a small farm with a few pigs, a cow, and some chickens, and it required someone to do the daily chores. Apparently, his parents had a lot of confidence in their nine-year-old son, because in the summer of 1951, they dropped off young Bill at the farm, where he lived by himself for one month. He explains:

“I was responsible for feeding and caring for the animals. My parents told me that if I had any problems, I should walk over to the neighbor’s house, which was about a half-mile down the road. And in the event of a dire emergency, I could use the phone on the wall. It was one of those old ones you had to crank, and I never once used it.”76

Bill was a nature lover and, as a young boy, wanted to someday be a forest ranger. But after reading a book about the life of Dr. Albert Schweitzer, he changed his mind. “I was enamored with his life’s work in Africa.”

Bill took Schweitzer’s words to heart: “I don’t know what your destiny will be, but one thing I do know: the only ones among you who will be really happy are those who have sought and found how to serve.”77 By the time Bill had finished the book, he had determined what he would do with his life. “I decided to be a missionary doctor. I wanted to contribute to humanity. I knew that someday I would.”78

By his teenage years, Bill had developed a strong work ethic, and observing his father’s bartering and scrap-collecting endeavors, he decided to make extra money by doing the same thing. The industrious teenager would find abandoned cars and trucks and remove the metal parts, which he would then sell to salvage yards. He did

well enough to pay for his own clothing and pay cash for his first car by the time he was fifteen. Bill graduated high school early and took a night job at Georgia-Pacific, earning enough money to pay for his education at the University of Oregon, where he studied for two years.

As a member of the cleanup crew at a Georgia-Pacific sawmill, he performed what was undoubtedly the lumber company’s least desired job. He explains:

“Those who had this job were paid for pushing a broom around, and they didn’t take pride in their work. This was evident from the sawdust and debris that had collected over the years in corners that were not cleaned. When the job was assigned to me, I took it upon myself to clean the place so it would look like a showroom. My thinking was that whatever your job is, you should do your very best at it. You must take pride in your work to avoid getting trapped into thinking, ‘I have a miserable job, and I’ll do as little as possible but enough to stay on the payroll.’ I believe you should find meaning in whatever you do.”79

Bill’s sentiments are reminiscent of the famous Martin Luther King, Jr., quote:

“If a man is called to be a street sweeper, he should sweep streets even as Michelangelo painted, or Beethoven composed music, or Shakespeare wrote poetry. He should sweep the streets so well that all the hosts in heaven and earth will pause to say, here lived a great street sweeper who did his job well.”

Between his sawmill job and operating his scrap business, the assiduous young man was able to pay his tuition and purchase a small rental house as an investment. The real estate transaction was relatively easy—so much so that he briefly considered buying many more properties, thinking that over time it would be a sure way to become rich. “It was something I believed I could do with ease,” he reflects, “but the notion of accumulating wealth was not my first priority.”80

To make extra money while in college, Bill also worked as a deliveryman for a furniture store. Noticing his young employee’s limited wardrobe, the owner gave him his old dress shirts. Bill recalls:

“They were good shirts, but the elbows of the sleeves had holes in them. I had accumulated three sweaters that were given to me as gifts during the past two years, and by buying two more, I was able to wear a different outfit for a full week. Being a good dresser for the first time in my life was good for my self-confidence. Then one day I noticed that people didn’t really care about how I was dressed. They were more interested in themselves. From that day on, I decided that I would only dress simply, so the focus would be on the other person. Every day I wear the same black outfits so that my attire will not become a subject of discussion, allowing the focus to move to the other person and their interests.”81

On the advice of Uncle Fred, his mother’s brother who lived in Minnesota, Bill transferred to the University of Minnesota. Bill points out, “This is where Earl Bakken, who developed the first wearable cardiac pacemaker, and Dr. C. Walton Lillehei, who is referred to as the ‘father of open-heart surgery,’ were making incredible medical advances in the 1950s. Lillehei performed the first successful open-heart surgery, and he developed new procedures for medical devices such as pacemakers and heart valves. I was interested in doing life-saving work, and knowing that researchers like Bakken and Lillehei were there, I thought it was the place to be.”82

BILL’S EPIPHANY

In 1961, to pay for his education while attending the University of Minnesota, Bill worked for his Uncle Fred’s company, Minnesota Hearing Aid Center, in a small shop that made earpieces for hearing aids. In the beginning, it was just a job. He had no interest in hearing aids. His intention was to work there solely to pay for his education. He explains his thoughts:

“My first impression was that the hearing aids business was rather mundane. Medicine had far more appeal. I’d be saving lives and be surrounded by young, attractive nurses.

“In those days, hearing aids were primitive compared with today’s. Control of feedback was a challenge. The molds had to fit tightly, and if not, the aids would whistle. My job was making the earpiece,

putting it on the patient, and testing it to make sure its seal was tight. One day I fit this elderly man, and the way he reacted afterward had a profound influence on my life. His entire face glowed with absolute joy. As long as I live, I will never forget his expression. When I observed that he could hear, it dawned on me for the first time what hearing truly meant. That night I said to myself, ‘Bill, the reason you want to be a doctor is so that you can help people. If you do this work, you will be able to help them and you won’t kill anyone.’

“I knew that over a lifetime, a doctor was certain to lose patients. I accepted this as part of practicing medicine. You can’t prolong life forever. As a young man, I knew that when I was a doctor, I could only do so much with my time and my two hands. However, with hearing aids, I could foresee when working with teams of people and the combined hands of many, I could contribute to improving significantly more lives.

“I used to have these conversations with myself. I’d say, ‘Bill, it is unlikely that you’ll ever be a Jonas Salk. You don’t enjoy chemistry, nor do you have the patience for research.’ I wanted the immediate satisfaction of treating a patient.”83

One night, the nineteen-year-old student had a dream, one that changed his life forever. He recalls:

“In my dream, I was talking to Bill Austin. ‘Bill, you’re a clinical guy. You are going to treat one patient at a time. Perhaps you will see fifteen or twenty a day.’ Then my dream fast-forwarded. I had a vision of myself as an old man in a casket that was being lowered into the grave. People were standing around the burial plot. The mourners were saying, ‘He was a nice old doctor, and he helped our community.’

“My immediate inspiration was that in the hearing aid business, I could contribute much more to the world. I could be a citizen of the world. I said to myself, ‘You have one life to live and one life to give. You must make it count for as much as you can. I can give the gift of hearing, the vehicle that creates love and caring between people. And it allows them to learn so they can live more productive lives.’ This thought changed the course of my life. When I awoke in the

morning, I knew exactly what I wanted to do. It was my destiny to serve people with hearing impairment.”84

Bill recalls his thoughts at the time and his attitude about the hearing aid industry.

“It was my opinion that it was on the slow track. That was okay with me. If you want to win, you should be on a slow track. I say this in candor, knowing that some people in this field might take this as an insult. However, I could see so many things that were being done inefficiently. I recognized that there was so much room for improvement. And I could see that during the course of making those improvements, I could attract a team of people, and with that core group, we could add teams of people. Then by multiplying this process, I could attain the leverage that was required to make a significant contribution to life.”85

That morning Bill rode a bus to work. On a panel on the ceiling, he read an anonymous quotation: “The true way to be humble is not to stoop till thou art smaller than thyself, but to stand at thy real height against some higher nature that will show thee what the real smallness of thy greatness is.” He recalls his reaction:

“I reread those words and repeated them until I knew them by memory. It was exactly how I felt. I wanted to challenge life. I wanted to be the best in what I did and still see the smallness of my greatest greatness. I was overcome with inspiration, but I had no leverage. I knew what I had to do. I had to build leverage, and I realized that it would take time, because I was starting out with absolutely nothing.”86

SCHOOL OF HARD KNOCKS

In 1961, Bill dropped out of school and went to work full time in his Uncle Fred’s hearing aid store in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. It was a replica of his uncle’s clinic in Minnesota. Only the name was different. In Sioux Falls, it was called South Dakota Hearing Aid Center. And like its sister clinic, Minnesota Hearing Aid Center, its name projected an image of a large company. Bill’s uncle owned several other stores like it throughout Minnesota and the Dakotas. All of

them were small hearing aid clinics, each having a staff of one to three employees.

The store was managed by an ex-school teacher. Bill recalls:

“There was so little traffic that one day the manager announced, ‘I can’t take it anymore. I quit. I’m going back to schoolteaching.’ I told my uncle that I can run this business, and just like that, I was his new manager. There were days when not a single person came in. We had a sales area and three examination rooms. A young woman in a white nurse’s uniform was always present in the front. I watched people that walked by take a peak at the window display, glance at the receptionist at her desk, and continue on walking down the street.

“Since they weren’t coming in the door, I decided to take a more aggressive approach. I went outside, and I waited for those window shoppers to come by. As they stopped to look at our window display, I approached them as if I were just or returning from a coffee break or lunch. I’d casually say, ‘Why don’t you come inside? We’ll check your hearing, and it will only take a minute. There’s probably nothing wrong and nothing needs to be done. But you might as well find out how your hearing is. It’s a free service we provide.’ It worked, and our sales shot up.”87

A natural-born salesman, Bill Austin is likeable, compassionate, and trustworthy. He has always had a strong work ethnic, and most importantly for a salesperson to succeed, he never took it personally when a customer said no. For this reason, he never became discouraged or lost confidence in his ability to sell. Above all else, he possessed a strong conviction in his product and services. This conviction was so evident that people sensed it, and they knew that what he did for them was in their best interests. All of these attributes are what it takes to succeed in the sales profession, no matter what the product or service is.

Bill didn’t rely only on window shoppers as prospective hearing aid patients. He would venture out away from the shop to solicit business. He explains:

“I would visit small towns in the area and go door to door down the street. ‘I am doing a survey. Is there anyone who lives here that

has a hearing impairment?’ If there wasn’t, I’d ask, ‘Do you know anyone who has a hearing loss or wears a hearing aid?’ In a small town, everybody knows everybody, so it didn’t take long for me to come up with a list of people with hearing impairments. Sure, not everyone was friendly, but enough were that I was able to get my foot in the door to serve people who needed hearing aids.”88

Once, he had called on an elderly couple in Woonsocket, South Dakota. He tells the story:

“I introduced myself at the door and said, ‘I understand you have a problem with your hearing. I test hearing.’

“‘My husband has a loss,’ the woman said.

“‘If you want to test our hearing, that’s okay,’ she said, ‘but I’ll tell you up front that we aren’t going to buy anything. It’s up to you, but you’ll be wasting your time.’

“‘Fair enough,’ I replied.

“As it turned out, they both needed hearing aids. They were very friendly and commented on how professional and courteous I was.

“‘Our son is Dr. Frank Lassman who heads the audiology department at the University of Minnesota. Do you know him?’ the husband asked.

“‘I don’t know him personally, but I do know of him,’ I answered. (Several years later, I did meet Dr. Lassman, and we became good friends.)

“‘Our son warned us that we should be aware of the Austin gang because they’re crooks,’ he said.

“‘Do you know who I am?’

“‘Well, no,’ they both nodded.

“‘I’m Bill Austin.’

“They both laughed, and when they saw I was serious, she said, ‘You can’t be. You’re much too nice to be Bill Austin.’

“They both bought hearing aids that night. I had a habit of selling just about everyone I talked to. That’s because I didn’t like to waste my time, and besides, I considered it a mental challenge to overcome their resistance. I felt that I was on a mission to help anyone who had a hearing loss. For this reason, I didn’t accept it when someone said,

‘No, I don’t want a test,’ or, ‘I’ll wait until later.’ It was just a game to see if I could be 100 percent effective.89

Bill acknowledges he didn’t bat quite 100 percent. “Nobody does,” he says.

“I did get chased off someone’s property. Actually it happened twice. Both times it was by husbands who didn’t want their wives to have hearing aids. These men simply didn’t want to spend the money on their wives. One husband said, ‘Every autumn I go hunting in the Black Hills, and if I bought my wife hearing aids, it would mean I couldn’t hunt this season.’

“‘You can’t be serious,’ I said. ‘Your wife has been your helpmate all these years and you would deprive her of her hearing so you can go hunting.’

“‘That’s right, young man. Do you have a problem with that?’ the man replied.

“I took great pleasure in telling him what I thought before I left.”90

Bill says that he recalls his failures as well as the names of all his early patients. He possessed a near photographic memory, and after every sales call, he would review what transpired. He explains:

“Every time I sold a hearing aid, it would be like coming back from the moon. As soon as I hit the seat of my car, I debriefed myself and I remembered every word of an entire conversation. I realized it’s about timing, the psychological impact. It’s not what you say but how you say it and when you say it. It’s creating the emotional why. I would go through this exercise and analyze what transpired, and I’d analyze what I did wrong—even when I made the sale. After every call, I’d ask myself, ‘How could I have been even better?’ I went through this exercise religiously.”91

The same analytical approach he applied to selling was his modus operandi in all facets of his career. He demanded constant improvement. Bill Austin was, and to this day is, a man obsessed with it. As he tells it, “I was constantly analyzing how to interface the device to the ear. I wanted to prove to myself that I was better today than last month. I drove myself to develop skills so that I could apply a hearing aid to deformed ears, surgical ears, and soft cartilage. I was

determined to help those with the most difficult hearing losses. As time went on, I realized that like people’s fingerprints, no two ears are the same.

“In a matter of time, I got to the point where I could sell and fit hearing aids no matter how tired I was, no matter how sick I was. At the risk of sounding boastful, I knew exactly what to do. That’s because I was so analytical about every phrase of this business. You meet all kinds of analytical people in other fields but not in this one. For instance, there are golfers who have an obsession for the game. They can have scratch handicaps, yet they are continually refining their swing. This is why I don’t play golf. This is what convinced me to say to myself, ‘Bill, there are too many golfers out there that keep taking lessons and keep learning.’ Well, I knew I’d never be an Arnold Palmer. In this business, however, I was seeing people who had learned the basics and then were doing it by rote, never analyzing what they are doing, and for this reason, they were remaining static. They reached a point where they never improved. I knew I could be better today than yesterday and better tomorrow than today. Consequently, I found it easy to leave the competition in the dust.

“My work is my hobby. It is my life. It is what I derive the most enjoyment from. There is no meal that could be prepared with the finest quality of foods and wines that would be as satisfying to me as the joy I receive from fitting patients. There is no entertainment—no Super Bowl or concert performance—that could match the enjoyment I receive from what I am able to do for my patients. Sometimes I think I am selfish because I am doing exactly what I want to do.

“People were trusting, and they trusted me. I expected them to trust me because I was going to do my best for them—and I did. I know making cold calls is a tough way to build a clientele, but that’s what I had to do. If this is what it took to help people, I was happy to do it. Sure, not everyone welcomed me with open arms. One time I called on a man who had been cheated by a hearing aid salesman. Somebody had taken his money and never delivered the hearing aids to him. When I knocked on his door and introduced myself, he shouted, ‘You people are crooks!’

“He was an old man, but his age didn’t stop him from picking up a chair and chasing me around his dining room table. I kept a few steps in front of him, and while I was being chased, I kept saying, ‘Hey, I’ve never been here before. I came to be of help. I’ll try to help you.’ Finally, he calmed down enough to hear me out. I was able to help him, and when he received his hearing aids, his hearing was restored. He was very grateful and referred several other hearing-impaired people to me.”92

With Bill running the store, business was brisk at South Dakota Hearing Aid Center in Sioux Falls. Bill was winning prizes for his sales production. Once, he won a suit, and another time, it was an all-expenses-paid trip to a hearing aid conference in Chicago. To his dismay, his uncle reneged on both the suit and the trip. Bill recalls:

“I sold more hearing aids than anyone else, and I was disappointed that Uncle Fred didn’t keep his word. However, I refused to let it get to me.

“Meanwhile, I had a lot of accumulated commissions that was being held in a reserve. Knowing these back commissions were due me, I put down a deposit on a cottage in South Dakota. My plan was to collect the money from my reserve so I could close the deal on the house. I asked Uncle Fred to mail it to me, but a check never arrived. If the check didn’t come soon, my deposit would be forfeited. I drove from Sioux Falls to my uncle’s office in Minnesota. When I got there, his assistant said that he was too busy to see me.

“‘I need my money so I can close on a house,’ I told her.

“‘I’m not authorized to pay you,’ she said, ‘so you’ll have to talk to your uncle.’

“I waited all day but kept on being told: ‘He can’t see you now; he’s with someone,’ or, ‘He stepped out for lunch,’ and, ‘He’s in a meeting and unavailable.’ At the end of the day, I drove back to Sioux Falls without being paid. As a consequence, I lost my deposit on the house. ‘I’ll never work for him again,’ I vowed, and I quit. I worked like a dog for my uncle. He never had a more loyal employee. Had he paid what was due me, I would have never left him.”93

A few days later, Bill was on an airplane to Oregon to sell the rental property he had purchased a few years earlier.

With the money from the sale, he went back to Sioux Falls and opened a small retail hearing aid storefront. Applying the same sales techniques as before, he slowly built his business.

Bill enjoyed modest success in Sioux Falls. Envisioning greener pastures in a larger metropolitan market, in 1967 he migrated to Hopkins, Minnesota, a suburban community of 15,000 just west of Minneapolis. Here he opened Professional Hearing Aid Service, a combination clinic and repair shop. Not only did he work with patients and repair hearing aids, he did repairs for other dispensers. He began fixing their equipment, and what they found most appealing was that he did it at a fixed rate.

In time, all brands came to Bill’s shop. He systematically broke them down and studied how they were built. He listened to how they sounded. He methodically analyzed them. Then he kept an inventory, sorting the various parts in bins and drawers. An intense improviser, Bill was usually able to make necessary modifications, and the unfixable became fixable. He developed a keen expertise on how hearing aids worked mechanically, and working with products made by a variety of manufacturers, he was privy to what each company did best.

Meanwhile, Bill continued to serve patients who came into his store. He reveled in the joy of restoring a person’s hearing. No matter how many repair jobs were in the back room, being one-on-one with a patient was what he most enjoyed. Everyone received his full, undivided attention. A perfectionist, he made sure each received the best hearing aid for his or her condition. Every mold had to be properly fit, and every fit must be made so it could be comfortably worn. A fitting that was off by the thickness of a coat of paint was enough to cause a hissing sound; a fitting that was too tight caused discomfort or even pain to the wearer. When it came to taking care of a patient, it didn’t matter how much time it took to make sure he or she received maximum results. Bill was not a clock watcher. There was never a meter running that kept track of his time with a patient. Yes, those in the reception area might have to wait for their turn, but few objected, because they knew that when it was their turn, they would be treated by a man who truly cared about their hearing.

As the owner of his company, Bill wore many hats. He put in a full day’s work with his patients, and nightly he could be found taking apart and reconstructing broken hearing aids. He also found time to make calls on other dispensers, buying their broken hearing aids and used parts they hadn’t bothered to discard. He was able to convince them that since they had never before used the relics collected in cabinets, they should sell them to him. Typically, a dispenser had twenty, fifty, or even hundreds that were just sitting there, and Bill Austin would relieve the vendors of what they viewed as nothing more than junk. Their junk was his treasure.

Professional Hearing Aid Service was building a good reputation for repairing hearing aids. However, its real growth came when the twenty-something-year-old entrepreneur decided to expand the company by providing equipment repair services at a set rate to dispensers. This opened doors to the hearing aid community across the country. It also required him to spend a lot of time on the road. Once in a dispenser’s office, he was able to buy their discarded parts, which he added to his growing inventory. Having accumulated a large stock of hearing aid parts, he solicited these same dispensers for their repair business. Within three years, his start-up company had more than thirty employees.

“My Uncle Fred passed away, and I got a call from his widow, Thelma,” Bill tells. “She said to me, ‘You owe it to me to buy our company.’ I wasn’t sure why I owed it to her; however, I bought the business because I knew she needed the money.”

STARTING STARKEY

Technically, Bill Austin didn’t start Starkey Labs. It was a company he bought in 1970. The company made earpieces for hearing aids and, in particular, ear molds. It was housed in a log cabin in Maple Plain, twenty miles west of Minneapolis. Paul Jensen had purchased the company from Harold Starkey, who had moved to Black Duck, Minnesota, to spend his remaining years. Bill paid $13,000 for the company with assurances from Jensen that he would stay on and continue to make molds.

“In his early thirties, Jensen had come to America. He was sponsored by his cousin, Harold Starkey’s wife. Jensen started working for his cousin-in-law in 1964, and five years later, he became the company’s new owner. Bill had molds made at Starkey, and one day he made Jensen an offer to buy him out. Bill explains:Jensen’s mother lived in Denmark, and he never had the time to visit her. He couldn’t get sick. If he had a cold and didn’t work, no molds got made that day. It was a one-man band. ‘If you sell me your company, you’ll get to see your mother,’ I told him. ‘And you’ll see the business grow.’ Jensen’s eyes lighted up when I said that. ‘When it grows, think of how we will be contributing to the employees. They will have more meaningful lives because their good work will enable people to hear.’ When I said this to Jensen, I could see in his expression that we were on the same page. I bought the company for Paul. Jensen was the best person I knew at cutting molds. I wanted his skills.”94

Under Jensen, Starkey had remained a small, three-person shop. In addition to Jensen, it employed a secretary and a man who was mentally challenged.

Jensen, who speaks with a heavy Danish accent, says, “Everything Bill told me came true. I did visit my mother in Denmark many times, and the business really grew. Two years later, Bill bought another company I owned, Jensen Supplies, that had an inventory of parts we used to build hearing aids. I received $30,000 for it. He was very fair with me, and I stayed with him until I retired at age eighty-one in 2008. The best thing I ever did was sell the company to Bill Austin.”

Following his $13,000 purchase, Bill moved the acquired company out of the log cabin and into his St. Louis Park site, where Jensen would continue making molds. He decided that it was also time for a name change.

“I’m going to change the name of Professional Hearing Aid Service to Starkey Laboratories,” Austin explained to Jensen.

“Why would you do that?” Jensen questioned. Why not name it Austin Labs?”

“I want this company to be bigger than I am. I don’t want it to be always associated with me. I want Starkey people to accept certain philosophical principles as their own. They should live by them, and when I am no longer here, these principles will live on. The most difficult job I will encounter—and it will be my last job—is to have built this company so that it can go forward and its people will not do everything that I did. Instead, they will adapt to the times, and at the same time, they adhere to our core values. For this to happen, they must take ownership in these principles.”95

Bill insists that he never had ambitions concerning money.

“I never said I hope that someday we’ll be a $10 million, $100 million, or $1 billion company. How big we are never mattered to me. Size isn’t what’s important. It’s the character you bring to work. From the day I decided to devote my life to the hearing aid field, I was determined to help people with their hearing impairments. I wanted to do it by being the best I possibly could be, and I wanted to constantly keep improving and growing. To accomplish this, I know I’d have to apply leverage so that a maximum of people could benefit. These are the bedrock principles I based my future on, and I want these principles to live on through the people that succeed me.”96

But why name it Starkey? Bill explains:

“Back in those days, there were so many hearing aid companies with ‘tone’ in them. There was Beltone, Goldentone, Audiotone, Microtone, Sonatone, and I wasn’t going to be another tone. Let’s do it our own way. We don’t have to copy what the competition is doing. It might take people time to get used to it, but we’re going to be the trendsetters in this industry.”

“Besides,” Bill adds with a smile, “I thought the name Starkey was a name that people could relate to. I liked the combination, ‘star’ and ‘key.’ We want to help people reach the stars and we want them to find their key to success.”97

When the deal for the company was finalized, Bill handed a check in the amount of $13,000 to Paul Jensen. “That was the last day I have ever written a check,” Bill states. “Since then, other people have handled money matters for me.”98

BILL AUSTIN’S EARLY INNOVATIONS

In the 1970s, Starkey Labs had steady growth spurts. During this period Bill came up with several innovations that forever changed the hearing aid industry. For the most part, the cynics resisted the changes he introduced.

When he was a student and made ear molds for his uncle, Bill was appalled by the lack of service in the industry. He couldn’t believe that no company offered a trial period allowing a customer to bring back a defective device for service. The industry edict was: “If you bought it, you own it.” There was no such thing as a return policy.

Once Bill operated his own shop, he instituted a very informal return policy. Customers didn’t have to pay anything unless they decided to keep the products. On occasion, there were individuals who returned hearing aids because they couldn’t afford to pay for them. Bill explains:

“If I knew a patient was truly so poor that he couldn’t afford to pay me, I’d say, ‘Keep them and you can pay whatever you feel comfortable paying, but I don’t want you be without them. I will trust you.’ We didn’t have a credit department. We had an honor system. It was the same way when we repaired aids for dispensers. Again, there was no credit department, and here, too, I said, ‘It’s an honor system, and I trust you. I will give you an open account. If you don’t pay me, your account will be closed.’ We rarely had someone welch, and by eliminating the costs of running a credit department, we were ahead of the game.”99

For practical reasons, patients could not keep their hearing aids indefinitely and then receive a full refund. They were given ninety days to make their decision. Today, the Food and Drug Administration requires a money-back guarantee, but Starkey was the first to offer it at a time when it wasn’t mandatory by law. Some competitors cried foul play. Others claimed, “Bill Austin is crazy, and it’s just a matter of time before his company goes belly-up.” When the company started to pick up market share, the competition declared that he would ruin the industry. There was one attempt to have Starkey blacklisted and a letter mailed to dispensers that called for a boycott. When it

became evident that customer satisfaction was high and the ninety-day return policy resulted in few returns, the boycott was totally ineffective. Within a few years, all of the competition came out with return policies.

Although Starkey Labs had matured into the industry’s leading repair company and continued making hearing aid molds, Bill never stopped fitting patients. Above all else, this was his first love. He enjoyed the excitement people had when their hearing was restored. Over time, he worked with thousands and thousands of patients. His vast experience combined with his quest for continual improvement proved to be a formula for success. He acquired superior skills and insight that even his competitors could not deny. Energized by his passion for his work, he worked long hours, always honing his craft. Driven to serve hearing-impaired people, he strived to find ways to make new products. He thought about his work every waking hour. Long before the phrase became popular by a best-selling inspirational book, Bill Austin lived a purpose-driven life. It was an obsession.

In the trade, the biggest objection to wearing hearing aids was a result of the stigma they carried. People are vain. They didn’t want to be perceived as impaired or elderly. Knowing his patients, Bill understood that people’s vanity played a significant role in their buying decision. The small laboratory had successfully cast inner ear molds. Bill wanted to make in-the-ear devices that were barely detectable. Up until this time, the behind-the-ear models were most commonly worn. Bill was sensitive to his patients’ needs. “We could do better,” he’d repeat. “There has to be a way where we can overcome this stigma and give them even better hearing.” Observing how patients unconsciously pointed to their ear when he tested their hearing, what should have long been so obvious became evident to him. “They point to the entrance of the ear,” he reasoned. “Of course they do. That’s because they don’t hear from behind the ear but from the ear’s canal. I am going to make devices that are placed in the ear.”100

In 1973, three years after the acquisition, Starkey introduced its first custom in-the-ear hearing aid. “It has to be this way,” Bill claimed, “because no two ears are the same.” Within the industry, the reaction was, “Customize each hearing aid for each patient? It

can’t be done. It will cost too much. This time Austin has lost touch with reality. It’s only a matter of time before Starkey is out of business.” The public didn’t see it this way. To them, customized in-the-ear hearing aids made a lot of sense.101

Because of the heavy demand, Bill went on a hiring spree and brought in experienced hearing aid technicians. It didn’t take the company long to establish itself as the leading producer of this revolutionary product. In 1975, Starkey moved into its current headquarters in Eden Prairie, a suburb of Minneapolis.

Randy Schoenborn is the president and owner of NewSound Hearing Aid Centers located in the South Texas area. NewSound has more than thirty stores and sells more Starkey products than any other hearing aid brand. Having known Bill Austin for over twenty-five years, Schoenborn says, “There is no other CEO of a major hearing aid company that has spent even a fraction of the time with patients as has Bill Austin. Based on many years of personal experiences, Bill recognized that people wanted small, unnoticeable hearing aids. Understanding the psychology of the patient, he emerged as the leader in promoting smaller and even smaller hearing aid devices. For instance, in 1973 Starkey introduced its first CE model custom-fit in-the-ear amplification device. Today Bill Austin is frequently referred to as the ‘father of the in-the-ear hearing aid.’ It was also Austin’s no-questions-asked return policy that led the way where other companies followed suit.”102

The custom in-the-ear hearing aid was a suitable antidote for people stigmatized by how they thought other people viewed them. Interestingly, having impaired hearing is comparable to having poor vision, but wearing eyeglasses doesn’t have the same stigma as wearing a hearing aid. This is true in part because hearing loss is more often associated with aging, and America is a youth-centered nation. Stigma aside, Bill plainly states, “If you need glasses, you get a pair. If you need hearing aids, you take care of it. It’s no big deal.”103 In addition to easing people’s self-consciousness about wearing hearing aids, the in-the-ear device helped improve their hearing. This improvement was possible because of the physiology

of the ear: the closer to the inside of the ear the device is placed, the more efficient the amplifying process.

There was no marketing and advertising blitz to launch the CE hearing aid with in-the-ear technology. In fact, it couldn’t have been more low-key. Bill recalls:

“On January 1, 1973, I sent a two-sentence introduction out in a letter to our dispensers. It read: ‘We do something besides repair hearing aids and make ear molds. We also offer an in-the-ear hearing aid worthy of your consideration.’ That was it. Brief and right to the point! From that moment forward, my problem wasn’t selling hearing aids. It was keeping up with the production and maintaining quality control.”104

To make hearing aids affordable to the needy, Bill started the Starkey Fund in 1973. In the beginning, dispensers recycled their used batteries through Starkey, and in turn they received credit that was donated to those who needed financial assistance in purchasing a hearing aid. Several years later this fund evolved into the Starkey Foundation, a vehicle of Bill Austin’s that fulfills his biggest dream—it provides hearing to the most needy people around the world.

By the late 1970s, Starkey was making diagnostic equipment and key research tools, including the CHAT hearing aid tester, the Tinnitus Research Audiometer, the HAL Hearing Aid Lab, the ST-1 Power Stethoscope, the BC-1 bone conduction aid, and the RE Series Probe Microphone Systems. These and other inventions were more sophisticated and patient-specific than what was previously available, and they led to future specialized development of hearing aid models.

In 1980, Starkey introduced the world’s first in-ear canal hearing aid. The INTRA was the latest of a series of hearing instruments made by Starkey. Each was a technological advancement that was smaller and less conspicuous to the wearer. It was an immediate hit, and phone calls came in from across the country from patients, dispensers, and audiologists.

FIT FOR A PRESIDENT

One call was from Byron Burton, a dispenser from Santa Anna, California, who was a Starkey customer and Bill’s good friend. From previous conversations, Burton recalled being told that ever since Bill was a small boy, he had been a big Gene Autry fan. Bill tells the story:

“Byron remembered a story I told him about when I was four years old and my Uncle George Austin from Oregon came to visit us in Missouri. I hid in my uncle’s car trunk because I knew he was heading back to Oregon. I wanted to go out West and see my hero, Gene Autry. Luckily, my hiding place was discovered before the car pulled out of the driveway. With my boyhood story of mind, Byron called me.

“‘Shooting blank pistols in all those cowboy movies caused Autry to have some hearing loss. He wants to be fitted for new hearing aids. Why don’t you come with me and you can fit Gene?’

“I went to Palm Springs where Autry lived and fit him. It was the start of a long friendship, and he was one of the reasons why I later bought a house in Palm Springs. I liked hanging out with Gene Autry. He was a good friend of Ronald Reagan from back in the days when Reagan was in the movies. Autry was quite satisfied with my work, and during a visit in 1983 at the White House, he told the president about his hearing loss and how well he was hearing since I treated him. Reagan also suffered significant hearing loss when a blank gun cartridge had been shot off close to his ear on movie sets. Autry told me how impressed the president was with the hearing aid I fitted him with and remarked that he couldn’t even tell Autry was wearing one.”105

Shortly afterward, Bill received a call requesting that he come to fit the president. Because of his loss of hearing, Reagan had been experiencing difficulties in his interactions with dignitaries and the press. Wearing imperceptible devices appealed to him. He was the oldest president in the nation’s history and conscious of his image. He didn’t want to appear as an elderly person.

To be sure, President Reagan had a lot of important matters on his plate. Shortly after the president received his new Starkey canal

aid, a Russian military plane shot down a Korean Air Lines Boeing 747 (Flight 007), killing all 267 passengers aboard, including a U.S. congressman and sixty other Americans. At first the Soviets denied any knowledge of the shootdown. Later, Premier Yuri Andropov admitted that Russian fighters downed the jumbo jet, justifying the shooting by saying it was on a spy mission for the United States that was flying through Soviet airspace. Of course, there was no basis for Andropov’s claim that the Korean jetliner was an American reconnaissance aircraft. This happened at a time when the Soviets and the United States were discussing nuclear arms reduction.

The Flight 007 incident dominated the news for weeks, and polls showed it was hurting President Reagan’s popularity. The White House needed a positive story to offset the negative news coverage. Meanwhile, his wife, Nancy, and staff members were commenting to him about how his hearing had vastly improved. The office of the White House press secretary picked up on this and announced the wonderful news about the president’s new hearing aids. The announcement was a boon to Starkey, generating enormous media exposure, particularly at a news conference when Reagan acknowledged Starkey by name and commented on his new state-of-the-art hearing aids. Millions of Americans and viewers worldwide could see that the president didn’t even look like he was wearing any! It was also newsworthy for the president to admit he had a disability and be so open about it. His openness had a positive effect on alleviating the stigma of hearing aids. If arguably the most important man in the world wore them, there was no shame in wearing hearing aids. It was a publicity coup for Starkey. Immediately, the phone was ringing off the hook. Bill explains:

“We received so many orders that our people were working overtime, including Saturdays and Sundays trying to keep up. However, the company experienced tremendous growth that came at a steep price. Quality control declined significantly. Getting parts was another problem. Repairs that took a week were taking a month or more. The back orders were piling up, and the company started to unravel.

“Someone once said to me, ‘Having such a jump on the competition with the INTRA canal aid, you must have made a lot of money.’ I replied, ‘No, it cost me millions of dollars because we had prosperity disease. We lost some good, longtime customers, and we experienced high service costs. We lived through it, although it took over a year.’”106

Ronald Reagan wasn’t the first VIP to wear Starkey hearing aids, but the pursuing news coverage on the president certainly caused more publicity than the company had ever experienced. “There were others prior to President Reagan,” Bill points out, “such as Buckminster Fuller, the famed American futurist and author of [Operating Manual for] Spaceship Earth; Japan’s emperor, Hirohito; and a few sundry kings and other celebrities.”107

Other U.S. presidents that Bill has treated include Gerald Ford, George H. Bush, and Richard Nixon. He has treated Jimmy Carter’s wife, Rosalynn, as well. Worldwide personalities include Mother Teresa, Nelson Mandela, Imelda Marcos, and Pope John Paul II. Other celebrities are Walter Cronkite, Billy Graham, Scott Carpenter, Carol Channing, Frank Sinatra, Paul Newman, Steve Martin, Arnold Palmer, and billionaire Warren Buffett. Bill thinks that the more open high-profile people are about wearing hearing aids, the less is the stigma to wear them. “Remember now,” he says, “these are not anything like your grandfather’s hearing aids.”108

In recalling the VIPs who have benefited by wearing Starkey hearing aids, a wide grin appears on Bill’s face.

“The word just spread around the world, and I often wondered, how do you know when you’ve really become a significant force in the industry? Well, I was looking at some orders that came in, and I happened to come across two orders. One was from a Russian commissar, and the other was from a prostitute from Thermopolis, Wyoming. She was embarrassed because her behind-the-ear hearing aid kept falling from her ear while she was engaged in various activities with her customers. It made me think, a commissar from Russia and a hooker from Wyoming. We have arrived! Now we are a real company! We were serving society at all levels and all places.”109

A FAMILY BUSINESS

In his early twenties, Bill had a brief marriage that ended in divorce. He has two children from this marriage, an adopted son, Greg, who works side by side with him fitting patients, and a daughter, Alex, who works in the company’s Government Services program. Brandon Sawalich, a son of his current wife, Tani, is the company’s vice president of sales and marketing. Tani’s other son, Steven Sawalich, is a film director who produces videos for the company. Tani is very involved in the Starkey Foundation, so it’s a family affair. She describes her husband as having a purpose-driven life: “He’s on the job 24-7. But I don’t consider him a workaholic. It’s just who he is. He loves it.”110 To Bill’s good fortune, his wife and children are active in the business.

Tani Austin grew up in the hearing aid industry. Her mother, Pat Manhart, who was divorced when Tani was a small child, has been a dispenser for fifty years. For twenty-five years, Pat operated her own hearing aid company in southern Illinois and then in California, where she currently has her own practice. “It has always been a part of my life,” Tani says. She continues:

“Patients were our gardeners and our babysitters. My siblings and I always made extra money working for my mother.

“When I was old enough, I had a franchise with Miracle Ear. I served on their franchise advisory counsel, and I was vocal about saying what was on my mind. My mother always cared about her patients, and I grew up sharing her sentiments. At Miracle Ear, the emphasis was on the dollar, not the patient.

“In 1990, after attending a counsel meeting in Minneapolis, I was at the airport waiting to board my flight to the West Coast, and I saw this tall, distinguished man with a head full of white hair. ‘Who is that guy? I know him,’ I thought to myself. It was Bill Austin, who had received an Entrepreneur of the Year award that I read about in a trade magazine. I knew of his reputation about how he cared for patients, so within a few minutes, I built up enough courage to walk over and introduce myself to him.

“Very quickly into our conversation, he started talking about product quality and caring about patients. He spoke with such conviction that I knew he was sincere. Still I couldn’t help thinking, ‘Is this guy for real?’ What he said was the opposite of what I had been trained in.”111

About six months later, Tani was still thinking about her chance encounter with Bill Austin. She had become disillusioned with her practice and decided it was time to either change or shut the doors. She explains:

“I called Bill and asked him for his opinion. He told me that Starkey was having a class that weekend for a group of its dispensers and invited me to attend. Our conversation was on a Tuesday, and that Thursday, I was on an airplane to Minneapolis.

“I attended the weekend session, and it was like having worked in black-and-white and going into living color. I immediately knew that this is what I wanted to do. This is what this business is about. When I got home, I changed to Starkey. I had a million-dollar business, but I was just selling hearing aids, and I didn’t like it. I closed four of my offices and let six people go. In no time, I was doing a better job, and I was having fun again. When patients came back after a week of wearing Starkey hearing aids, they’d say, ‘I love these hearing aids and have been wearing them all week.’ At Miracle Ear, we’d tell them to wear them just one or two hours a day and ‘you’ll soon get used to it.’ I realized that Starkey’s technology was far superior to the competition. This is what made my work fun again.

“I was so enthusiastic about the product and applying the Starkey program, I had immediate success. I kept sending my results to the marketing department, and one day Bill called me. ‘I wish my salespeople would listen to me as well as you do,’ he said. ‘I think you are the only person in the country that listened to what I said that day.’

“‘I remember saying to my father that night, ‘I think Bill Austin offered me a job, and I would like to take it.’ I called Bill back and asked, ‘Did you just offer me a job?’

“‘Well, maybe,’ he said.

‘I would really like to do it. I will show other dispensers how I do it with my practice so that they will do a better job with their patients.’”112

Tani started working for Starkey in Minneapolis in January 1992. And as Tani says, “The rest is history. Bill and I dated. That May, we moved to Dallas, where Starkey had a distribution facility, and lived together for eight years. We were married in 2000.”113

Greg Austin studied the acoustics of sound at Camden County Community College and then spent the next few years learning how to train racehorses. Afterward, he went back to college to study the physiology of hearing. When he came aboard full time, he worked in several different departments ranging from manufacturing to the business side of the company. Today, approaching age fifty, he works side by side with his father, fitting people for hearing aids. “To me,” he says, “the most rewarding job here is working with the patients. What makes this so special is that every day I get to see how my work impacts people’s lives.”114

A chip off the old block, Greg adds, “My father has a lot of compassion for people and, in particular, for those with hearing problems. He has a successful company today, and he could be busy running it all day, or if he wanted to, be on the golf course or on a yacht enjoying the good life. But this is what he enjoys more than anything else. My father put together a team of top managers, and he lets them run the company. He trusts them explicitly, and this frees him to do what he literally lives for. It’s a calling he has. Like I said, I could be working in other areas of the company, but I followed in his footsteps because I share his passion for working with patients.”115

Greg believes that when employees see his father working with patients every day, it sends a message that the patient comes first. “It doesn’t matter if you’re in accounting, engineering, or sales,” he states. “The patient is our top priority. When Starkey people see that the company founder and CEO is totally focused on the patient, it lets them know what the number-one priority is around here.”116

Everyone who knows Bill Austin, with his years of experience and dedication to constant improvement, shares the opinion that he is the world’s best at fitting patients for hearing aids. Bill doesn’t

dispute the fact. He is certain that this is true. It is not his ego saying this—it’s a fact. Like a great heart surgeon who makes split-second life-and-death decisions, Bill has confidence in his abilities in what he does. He says, “If I can find someone better than I to do a job, I stop doing it and let that person take over so I can conserve my energies to be used for needed tasks and thereby better use my time. Well, I used to think I was the best wax guy in this field—I could clean ears better than anyone else, better than any doctor. Then one day I watched my son. Now, I have steady hands, but Greg’s hands are even steadier. His hands are perfect. He could have been a fine surgeon. I watched him working and I said, ‘I quit.’ Greg does it now because he’s the best at it.”117

There are many companies that employ relatives of the boss but are never described as a “family business.” But the description fits Starkey. That’s because employees feel like they work in a family atmosphere where people care about each other. It starts at the top with Bill Austin.

Ray Woodsworth has good reason to feel this way about the company. Ray was a hearing aid dispenser in North Carolina when he met his wife, Laura, a Starkey employee, in 2001. He and other dispensers had been invited by the company on a Caribbean cruise. Ray and Laura fell in love, and to be near her, Ray took a job at Starkey’s Center for Excellence in Eden Prairie, where he currently works closely with Bill fitting patients. When the couple got married, the wedding ceremony and reception were at the Austin house.

As mentioned previously, today, Randy Schoenborn owns NewSound Hearing Aid Centers in Texas. In 1983, Schoenborn’s father-in-law, Dr. Harlan Conkey, who has a doctorate of education in audiology, recruited him to the company. Dr. Conkey had been a general manager at different Starkey manufacturing facilities in Canada, Oregon, and Texas. Working initially under his father-in-law’s guidance, Schoenborn was eventually promoted to the position of general manager of a Starkey facility in Austin, Texas.

In 2001, Starkey acquired a three-store company from an Austin dispenser. Its original owner operated the three stores for the next twelve months and then left the field altogether. Being based in

Austin, Schoenborn was asked to manage the three stores until other arrangements were made to sell them. He says, “I kept my general manager’s job. I took over the books and managed the people at the stores. Although time consuming, I enjoyed it.

“Bill and I would talk from time to time, and in reference to the stores, he’d ask, ‘How’s everything with your retail business, Randy?’

“‘I’m really having fun with it.’

“‘That’s interesting,’ he’d say.

“These conversations went on for a while, and one day he asked me, ‘How much time are you spending at the plant?’

“‘Not a whole lot,’ I answered. ‘Bill, I really like the retail side of the business and think I want to go in that direction.’

“He said that would be fine and never pressed the issue. He let me decide what I wanted to do. A couple months went by before we met in person, and we made a deal whereby I would leave the company and buy the three stores. It was a very easy transition. I followed the principles that I learned from Bill over the years—caring about people, building relationships, and knowing that I was put on this earth to serve people. These principles were a very good formula to succeed in any business.”118

Schoenborn is grateful to Bill for providing him with the opportunity to buy the small retail chain from the company. He is also appreciative for what happened just prior to his departure. He explains:

“Ten years earlier, my sixteen-year-old son, Jake, had brain surgery to prevent seizures. In 2002, he required additional surgery at St. Paul’s Children’s Hospital. Bill delayed taking me off the payroll so my son would be included in the company’s health plan. Jake’s medical expenses over the years have exceeded $1 million, and as a privately owned company, a lot of that comes out of Bill’s pocket. All I can say is that Bill is a very generous man.”119

Bill’s generosity extends to family, friends, and strangers. A few years ago, a farmer from Arkansas came to see Bill to be fitted for hearing aids. When Bill put a video otoscope in the man’s ear, he discovered a tumor. He explained the problem to the man and was told, “I’m fine. I’ll take care of that later.”

“You’ve got to get this looked at now,” Bill said.

“Later, but right now I can’t afford it.”

“I’m sending you to Michael Paparella, a friend of mine who is an excellent ear, nose, and throat specialist,” Bill insisted.

Reluctantly, the farmer consented, and a Starkey employee drove him to Dr. Paparella’s office. Following an examination, the man was admitted to a local hospital for surgery. The surgery was successful, and the farmer fully recovered. Bill paid the entire cost, which exceeded $20,000.

Asked why he paid the farmer’s medical expenses, Bill modestly replies, “When you extend a helping hand, it enriches the other person’s life as well as your own.”120

YOU WIN WITH PEOPLE

Back in the days when Bill had an epiphany to make a positive difference in other people’s lives, he was certain that by applying leverage, he could multiply his efforts by delegating the operations side of the company to others. By doing so, he would be free to personally work with individual patients. For years now, this is exactly what has occurred. Today, he spends most of his time with patients, and the managing of his $700 million company is delegated to others. More than 400 audiologists work at Starkey Labs now. Today, the company employs more audiologists than any enterprise other than the government. Eight audiologists work alongside Bill fitting patients all day. Patients referred by dispensers and audiologists daily trek to the fifteen-acre campus of the Starkey Center for Excellence to see Bill Austin. Many of them are the most difficult cases. For this reason, they come from afar to be treated by the man who invented the custom in-the-ear hearing aid—a man reputed as the best in the world at his craft, a man who has fitted far more patients than any other person on the planet.

Of the big six hearing aids manufacturers, Starkey is the only one that is headquartered in the United States. The other five are Oticon, ReSound, and Widex, all three based in Denmark; Phonak in Switzerland; and Siemens in Germany. Of these companies, Starkey is the only company still owned by the founder. Be assured that Bill Austin is the only CEO of these companies who treats patients daily; although, in fairness to the others, he may be a one-of-a-kind in any industry. It is doubtful that there is another CEO of a sizeable company who is as hands-on as Bill Austin. CEOs that head pharmaceutical companies don’t prescribe medicine. CEOs of automobile manufacturers don’t assemble cars. Perhaps CEOs and senior managers at other companies should find ways to spend at least a minimum of time with their customers. By staying close to customers, Starkey has managed to stay ahead of the competition. There is nothing quite like a CEO being on the firing line and getting firsthand information straight from the customer.

Tani and Bill Austin speak to a little boy on mission in Delhi, India, in 2008.

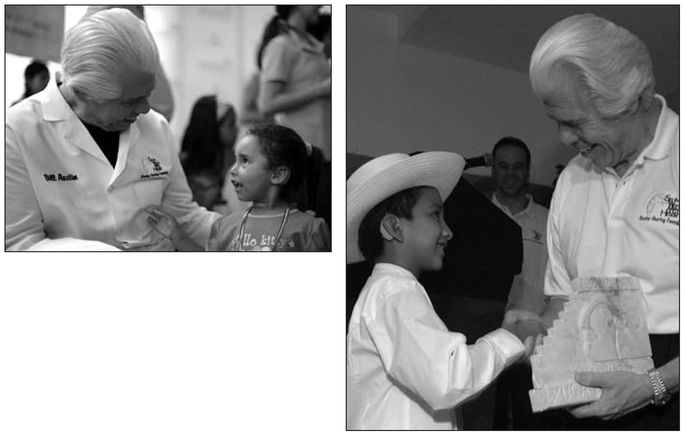

Bill Austin listens to a little girl in Lima, Peru (above), and shakes hands with a young boy in Panama who presents him with a statue (right).

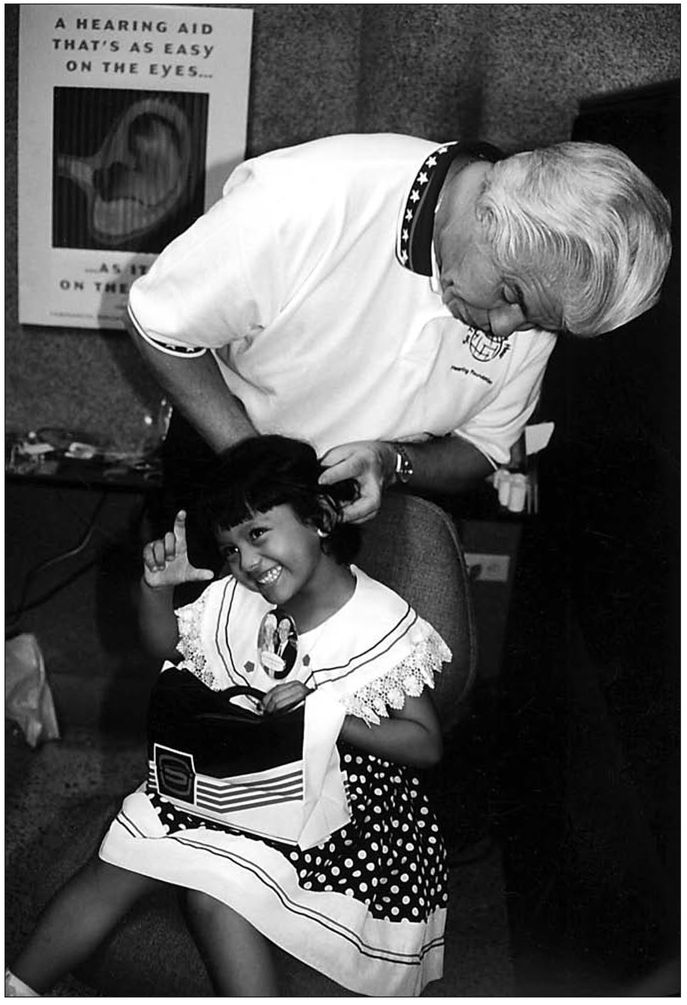

“A little more volume, please.” A young girl in El Salvador smiles about the new hearing aids she’s receiving.

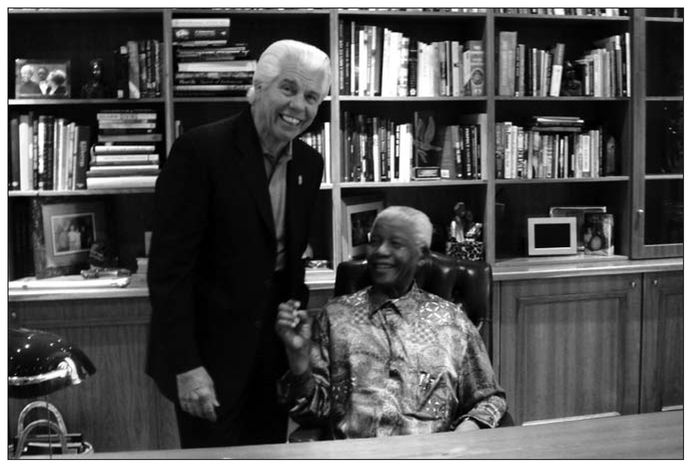

Fellow humanitarians Bill Austin and former South African president Nelson Mandela meet in Mandela’s office on October 29, 2008 (top).

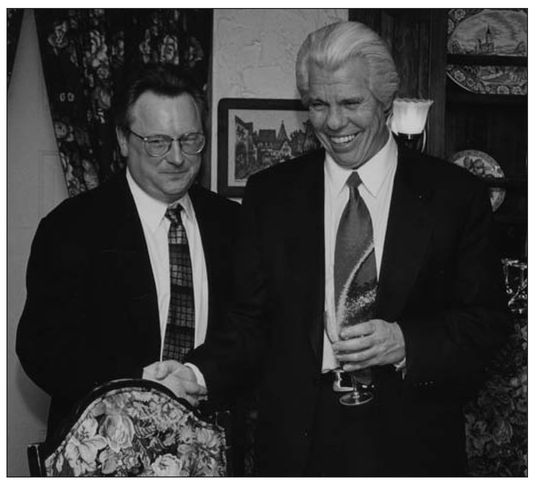

Passing on the torch: Bill Austin with Jerry Ruzicka, Starkey’s newly named president, on January 1998 (bottom).

But then somebody has to mind the store. Without a strong management team in place, Bill could not spend long hours seeing patients. A CEO must have absolute trust in his management team’s capabilities to run the company and, equally important, stay out of their way. A common tendency of entrepreneurs is to think that no one else can run the business as well as they can. Without delegation, such enterprises have limited capacity to expand. To Bill’s good fortune, he is surrounded by top-notch people who he trusts explicitly.

One such person who has earned Bill’s confidence is Jerry Ruzicka. Ruzicka joined the company in 1977 at age twenty-one, just after receiving a computer technology degree. For a short while, he had worked at Telex in its hearing aid division. Using his technology background, Ruzicka started out at Starkey as a repairs technician. Starkey quickly realized his supervisory potential and within two months promoted him to the position of line leader. In this capacity, he managed a small group of assembly-line workers. Before the end of his first year, he was promoted to department manager. His real talent surfaced when he found ways to shorten the time between when a repair order came in to when the hearing aids were fixed and shipped back to the customer. Ruzicka explains:

“Getting repairs out the door quickly is crucial in this business. It should only be here a couple of days. If your television set doesn’t work, you can survive without it, but when you can’t hear, you’re

unable to participate in life. Bill has always been totally focused on a fast turnaround, and frankly, I was good at helping him improve the service and turnaround time. I continued to grow with the company, and by the time I was twenty-nine years old, Bill promoted me to vice president of manufacturing. In 1998, I became the company’s president.

“Bill kept giving me more responsibility because he believed I could handle it. Every time I took on a new job, I continued to maintain my old job, too, so my responsibility kept expanding. As vice president of manufacturing, I kept looking at what had to be done next, and shortly after taking on this position, I started developing the company’s engineering group.”121

Ruzicka learned a lot from his boss and mentor. In particular, he adapted well to Bill’s philosophy of caring for people. Ruzicka says, “Most unusual is how Bill lets people grow. I quickly learned that he never sets specific goals, and in fact, he’s never told me what to do. But he always asks me, ‘What are we doing, and how are we going to do it better?’ This is very powerful. For instance, somebody can say, ‘Well, you are going to run a three-minute mile.’ But if you are running a six-minute mile, and you’re told that you’re going to run it in three minutes, your reaction will be, ‘No way. I can’t do that.’

“However, if someone says, ‘You are running a six-minute mile, and we want you to improve on that,’ you accept the challenge. You ask yourself, ‘What do I have to do to get better?’ It might be losing weight. It might be more training. So it causes you to think about various things. This is more effective than saying, ‘I want you to grow the company by 30 percent.’ Asking the question, ‘What are we doing to get better?’ made a huge difference on how I view what we can do as a company. This supports Bill’s philosophy, which is based on service.”122

Since the time when Ruzicka joined Starkey, annual revenues have grown from $8 million to $700 million. Ruzicka emphasizes, “As a big company, we keep trying to be a small company. We value the relationships that we make with our customers—dispensers and audiologists—and our job is to build strong relationships with them.

To do this, we have to help them do a better job, because what it all boils down to is doing what’s best for the patient.”123

Ruzicka points out that all people in leadership positions at Starkey know a lot about the company’s products.

“When working with patients, Bill is always searching for ways to make our products better. Like Bill in his early days, I was a repair technician, and I also built new hearing aids. Many of the other companies in this industry have marketing and research organizations that are telling them how their products are working and what the customers are saying. In this respect, we are an anomaly. We don’t hire any outside sources to take surveys. We don’t because we are so hands-on, and that evolves from Bill. It is in our DNA, and it is who we are. When we are developing a new product, Bill doesn’t participate in the strategy of what that product should be. But when we have the first one ready, he’s the first to get it, and he’s going to use it on patients. Rest assured, he is going to be our most critical customer. He will be our toughest customer. We want to give him a product that will make him proud and he’ll tell us how great it is. When this happens, it’s an improvement, and we’ll go forward. When we know that we’ve helped him to do a better job with his patients, we know that we succeeded.”

The company president pauses briefly and adds, “I can’t imagine any CEO being more hands-on than Bill Austin. He’s constantly dealing with the end user, and because he is, the rest of us are drawn to that. Another thing about this company is that there isn’t a lot of bureaucracy in this organization. Bill can walk into anyone’s office, pull up a chair, and talk. So can I and anyone else here. By removing layers of bureaucracy, your message doesn’t get watered down. It’s a family atmosphere where people aren’t afraid to talk to one another.”124

In 1994, Brandon Sawalich started his career at Starkey at age nineteen. Like his stepfather, he began in the repair lab, buffing and polishing and sorting old hearing aids that were sent in for repairs. He worked with all makes and models, learning the nuts and bolts of the business. Brandon says,

“When you’re nineteen, you think, ‘My mother is engaged to the boss; boy, I’ve got it made.’ In reality, it was the exact opposite. I was under a microscope where everybody was watching what I did to see if I was getting special treatment. Bill wanted to make sure that I learned the business by starting with the basics. This way, I’d have a future in the business. He made sure I learned the blocking and tackling. Had he started me out in a cushy job, I would have been set up for failure. Although I didn’t appreciate what he was doing for me at the time, I do today.”125

Brandon worked his way up the corporate ladder starting on the ground floor, and in his mid-thirties, Brandon is vice president of sales and marketing. Nobody who has followed his career ever claimed that Brandon got to where he is today because he’s related to the head honcho. All agree that he has earned his stripes. A personable and energetic man, Brandon is well respected by his coworkers and peers throughout the industry. And much like his stepfather and mentor, Brandon has a deep passion for the business. It would be hard for him not to. He has been exposed to the hearing aid industry since he was a small child. His mother and his maternal grandmother were hearing aid dispensers. “I didn’t want to be in this business as a young boy,” he confesses. “Like other kids, I wanted to be an astronaut or something more fun.”126

As vice president of sales and marketing, Brandon heads a sales force of more than 200 people. In this position, he contributes to developing the marketing strategy. He sums up his job by plainly saying, “I’m responsible for getting orders in the door. Keeping the place open.”127 As it is said in sales parlance, “Nothing happens until something is sold.”

When asked to describe the company’s sales and marketing strategy, Brandon explains, “It’s basically about making sure that we are serving our customers better than anyone else—that we are engaging with our customers better than our competition.” 128

When Brandon talks about the company’s customers, he’s referring to the 5,000 or so dispensers and audiologists that sell Starkey devices to end users. He explains:

“This is our customer base. When we advertise, it’s generally in trade magazines. We don’t advertise directly to the public. We don’t attempt to build the brand, because this is a people business. It’s like when you get a hip replacement. You don’t ask who makes the artificial hip. You don’t care. You want the best doctor and the one who will give you the best care. It’s not about building the Starkey name; it’s about providing the best product and service to over 5,000 customers that, in turn, serve their patients.”129

In addition to the daily calls made by the sales force to provide everything from technical information to fitting information, there is one other significant service that the company provides to its dispensers and audiologists. What puts Starkey in a league of its own is the way it educates and trains its customers. Throughout the year, Starkey conducts about forty invitation-only seminars that include two days of intensive classes at Starkey’s headquarters. Approximately 200 customers at a time migrate to Eden Prairie, where they take crash courses on how to better serve their patients. The company picks up the tab for their airfare, lodging, food, and beverages from the time the customers arrive at Minneapolis-St. Paul Airport on a Thursday to when they head home that Sunday. Which customers, prospects, and new accounts are invited to these sessions is determined by the sales staff.

The classes are professionally conducted and provide the best continuing education in the hearing aid industry. During these four-day visits, customers are able to exchange ideas with their peers. Tours of the company’s manufacturing and repair facilities are conducted, and visitors are able to meet the men and women who make and service Starkey products. They see Bill Austin working with patients, many of whom are the most severely hearing impaired. Sometimes, they may catch a glance of a celebrity who is there for a fitting.

Many of the hallways and walls of the Center for Excellence are adorned with large photographs of the rich and the famous who use Starkey products. These photographs serve a dual purpose. First, they let visitors know that VIPs who are hearing impaired are not slowed down; this message helps to remove the stigma associated with using hearing aids. Second, when customers discover that past presidents,

heads of states, show business people, and other well-known people use the company’s products—individuals who can afford the very best—it sends a message that the most discriminating people in the world wear Starkey devices. It is likely that many dispensers and audiologists make this point to their patients. In reference to the VIP photos, Brandon comments: “We don’t make a big deal about it. We let the photos of these high-profile people speak for themselves. They serve as testimonials.”130

Brandon refers to the customers’ visits to the home office as “the Starkey Experience.” He comments:

“When they take their time away from their personal and professional lives, we want to make it worth their while. From our viewpoint, we think of them as the most important people in the world, and we make sure to go that extra mile to make them feel special.

“Our competition is trying to figure out how to beat us. They keep asking themselves, ‘Why Starkey?’ Well, it’s pretty simple. It’s about the people. It’s not about some brochure, and it’s not just about a product. Starkey is a community. Everybody who works here does it for more than a paycheck. They truly have heart and passion. This is what separates Starkey from the competition. When our customers come here, this is what they take away when they go home.”131

THE MISSIONS

The World Health Organization reports that there are 280 million people around the world who suffer from moderate to severe hearing loss. The report estimates that two-thirds of them live in developing countries, and most of them would benefit from hearing aids. In the United States, it is projected that there will be a population of 33 million hearing-impaired individuals in 2010.132

In 1973, Bill agreed to donate free hearing aids to dispensers who in turn gave them to their patients who couldn’t afford them. The program was called the Starkey Fund. These donations were on the condition that the dispensers would provide free fitting services to the recipients.

Bill got his first opportunity to give away free hearing aids outside the United States in 1974, when a hearing aid dispenser from California called him for a donation. The caller was with a group that called themselves the Flying Samaritans. These people flew to Mexico on private planes to help poor people in remote rural villages. “A friend of mine is a doctor in Mexico,” the dispenser told Bill, “and he knows some children that badly need hearing aids. Can you help us out, Bill?” Bill tells the story: