CHAPTER 4

The First Pillar: People Quality, Focus, and Dedication

The quality, focus, and dedication of board members is critical. Directors need to be committed, competent, and qualified, possessing both the expertise and the willingness to contribute. A board that lacks the right composition, does not focus on the most important issues, or whose directors are insufficiently dedicated, is at risk of major failure.

A case in point is the Toshiba accounting scandal, where individual and institutional corruption at the 140 year-old Japanese electronics conglomerate went undetected by its board of directors.

Quality

Expertise and competence are essential attributes of any high-quality board. In this regard, skill maps are a useful tool for not only assessing the range of competencies of the current directors but also for specifying the skills, attributes, and even personalities required for effective board work – and for addressing any gaps between the board's current and ideal composition. The fit between the skillset of each member and the board's requirements is what counts. There is no ideal skill map, and typically it should extend beyond professional experience to include personal attributes and personality traits, as exemplified in Table 4.2 at the end of the chapter.

Table 4.1 Traditional Board Competencies (Rating From 1 to 10, With 10 Full Expertise and 7 Proficiency)

Sources: Multiple.

| DIRECTOR | CANDIDATE | |||||||||||||

| Experience/skill | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Accounting/financial expert | ||||||||||||||

| Governance experience | ||||||||||||||

| Strategic planning | ||||||||||||||

| Innovation and technology Digitalisation Partnering experience |

||||||||||||||

| Value creation | ||||||||||||||

| Regional experience Business transformation |

||||||||||||||

| Prior audit committee experience Prior nomination committee exp. |

||||||||||||||

| Other committees | ||||||||||||||

| Industry experience | ||||||||||||||

| Investments | ||||||||||||||

| Capital formation | ||||||||||||||

| Capital markets | ||||||||||||||

| Financial services | ||||||||||||||

| Information technology | ||||||||||||||

| Legal & regulatory compliance | ||||||||||||||

| Asset management | ||||||||||||||

| Risk management | ||||||||||||||

| Securities analysis | ||||||||||||||

| Joint venture management | ||||||||||||||

| HR | ||||||||||||||

| Cross-culture experience | ||||||||||||||

| Geopolitics | ||||||||||||||

| Turnaround experience | ||||||||||||||

| Other outliers as required | ||||||||||||||

Diversity – of industry, professional background, gender, personality, and opinion – also improves the quality of board decisions, in particular when creativity and innovation are required. By bringing in a range of specific types of expertise, diversity can enhance the board's ability to consider different solutions and reframe issues.

Diversity in terms of personality is important on a board, but can be uncomfortable. (One instrument for understanding differences in personality is the NEO-PI, which we discuss in greater detail in a later chapter on diversity.) Gender diversity is also important; boards with more women are likely to explicitly identify criteria for measuring strategy, monitoring its implementation, and developing and monitoring a code of conduct, for example.1 However, poorly managed diversity can sometimes lead to communication difficulties and decreased trust, which are disruptive. Boards therefore need to develop processes to leverage and manage diversity well. We explore how to achieve effective diversity in Chapter 23.

Focus

Even an excellently composed board will underperform if it does not focus on the most important issues. Because their time is limited, boards need to be strategic about their work for the organisation. This means figuring out what matters most, rather than simply having a precooked agenda meeting after meeting. Relying on the charter's definition of the role of the board is therefore not enough. In fact, being proactive in defining the board's role can help directors decide on their priorities. The ability of board members to clearly understand the role of the board in the organisational context, to focus on the right issues, and to prioritise is crucial.

Figure 4.1 below,2 which is based on the board of a sovereign wealth fund, outlines the classical roles of the board and the nature of its corresponding involvement. In general, a board may concentrate more on internal or external issues. Many boards that used to be highly focused on internal matters, including audit and performance review, now spend more time addressing external issues such as regulatory trends and geopolitics. Another dimension to consider is whether the board's primary task is to support the success of management, or to supervise and monitor it. This will depend on the maturity of the management as well as the context of the organisation.

Figure 4.1 The Roles of the Board. Source: Adapted from Strebel (2004)

Boards need to achieve on all fronts, of course, but because of time constraints will prioritise what matters most to the organisation. Often, board members will have different views in this regard. By working along a graph like the one below, they can understand their differences and build alignment. In the example underneath, members of one board – including three government ministers and other leading chairpersons – put a star in the quadrant they saw as the board's top priority and possibly a second one in their second priority. The exercise revealed a lack of alignment among directors as to where the board should focus its priorities. This was resolved through a session dedicated to improving focus.

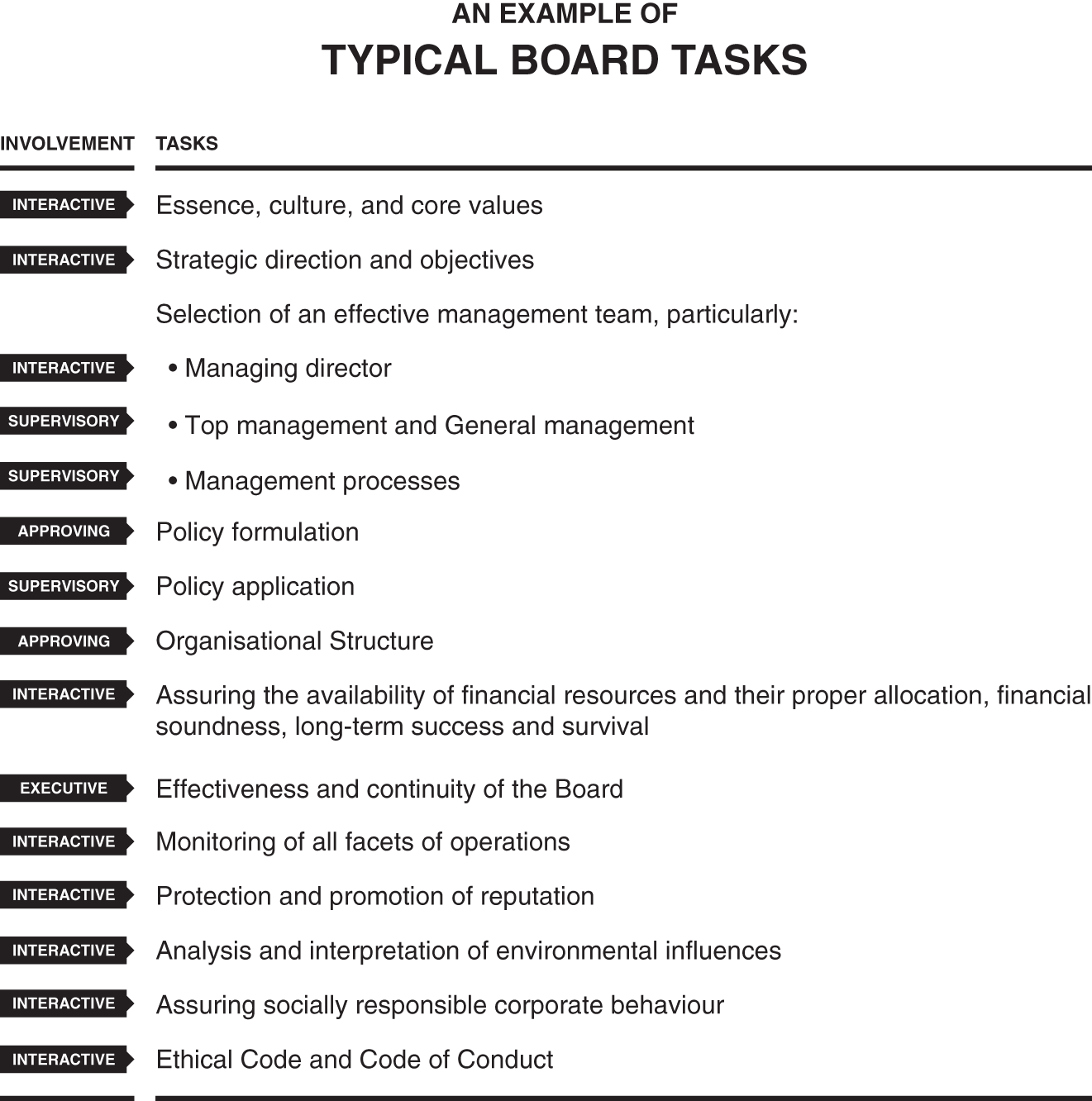

Figure 4.2 An example of typical board tasks

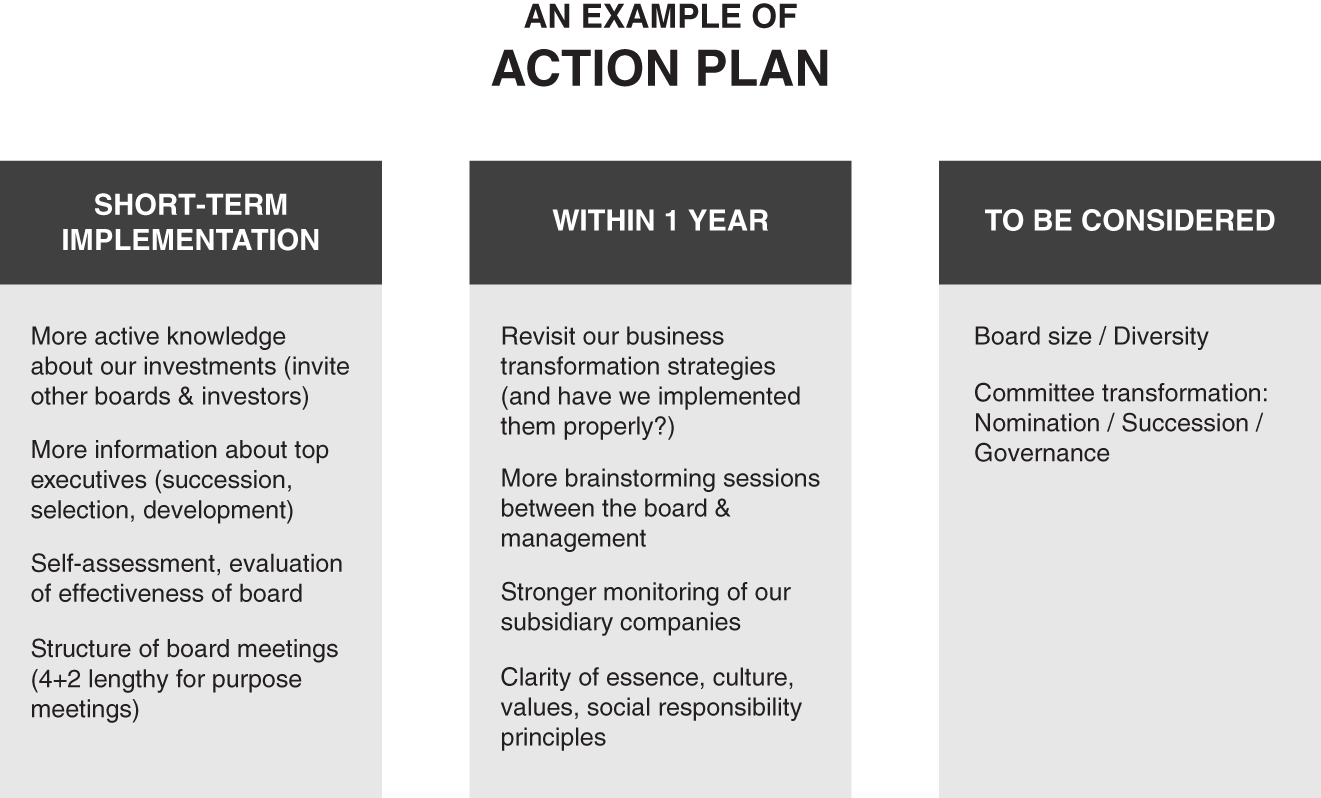

Once it has achieved a certain alignment regarding its role, the board can focus on elaborating a list of main tasks. These will then be incorporated into a two- to three-year action plan that will guide the board's work more productively than a traditional passive agenda could. Figure 4.2 below highlights some of the typical tasks that boards undertake, while Figure 4.3 summarises the action plan of that sovereign wealth fund board.

Figure 4.3 A board action plan from a sovereign wealth fund

Dedication

The most effective board members are more than simply competent and conscientious – they are individuals with genuine passion, energy, and dedication who are not motivated solely by the financial or social rewards of board membership. Board members must spend enough time keeping up to date on relevant issues and preparing for meetings, including through conversations with fellow directors. Norms in terms of preparation time have increased dramatically; according to a KPMG survey, for large organisations, one hour of board meeting requires 17 hours of preparation. As we saw in Chapter 1, many directors spend much less time than this. But the best board members always go the extra mile in their preparation.

The first pillar of board effectiveness is about people, and in particular their quality, focus, and dedication. All three of these dimensions are important, and none are ever perfect, of course. The board's composition needs constant adjustment, by understanding members' weaknesses and addressing them through education and other means. A smart board will seek a strong, dynamic focus on the right issues, and will set a yearly agenda that prioritises and caters for these. Finally, dedication needs to be watched constantly, because some are good at faking it. Good board work requires some skin in the game, and not necessarily in a financial sense.

As well as the right people, boards also need to have the right information in order to be fully effective. This is the focus of our next chapter.

Table 4.2 Example of Board Skill Map

| The Board Skill Map provides you with a simple tool with which to assess the knowledge level and personal attributes of your directors across various board critical dimensions. It can be used whether the board has a choice of directors or not (owners' representatives). Personal attributes matter as much as skills. Note that the personal attributes in this skill map could be used in other organisations, including for profit corporates, technology, oil and gas, financials, etc. This document is meant to be used for your self-assessment purposes and should be adapted to the organisation. Through administering it will offer you an overview of your board's competency, personality, and attribute gaps. This specific skill map was established for a non-profit: a sports organisation specialising on the fight against doping. Any skill map needs to be adapted to the characteristics of the organisation. | ||||||||||

| HIGH LEVEL SKILL MATRIX | Board members | |||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||

| Status (e.g. ED/ NED/Independent) | ||||||||||

| Director since | ||||||||||

| Age | ||||||||||

| Board of Director Experience (Y/N) | ||||||||||

| KINDLY RATE THE BELOW SKILLS | ||||||||||

| 1 No Knowledge |

2 Some Knowledge |

3 Good Knowledge |

4 Strong Knowledge |

5 Expert |

||||||

| SECTOR EXPERIENCE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| Sports direct | ||||||||||

| Sports related | ||||||||||

| Medical direct | ||||||||||

| Medical related | ||||||||||

| Government/regulatory direct | ||||||||||

| Government/regulatory related | ||||||||||

| GROUP TECHNICAL SKILLS I | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| Management | ||||||||||

| Accounting | ||||||||||

| Legal | ||||||||||

| Chemical/biology | ||||||||||

| Human resources management | ||||||||||

| Communication | ||||||||||

| Core technical | ||||||||||

| General technical | ||||||||||

| Scientific | ||||||||||

| GROUP TECHNICAL SKILLS II | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| Sector – commercial | ||||||||||

| Funding | ||||||||||

| Government and regulatory affairs | ||||||||||

| IT/ Digital | ||||||||||

| Legal – anti-doping | ||||||||||

| Legal – general | ||||||||||

| Marketing | ||||||||||

| Risk management | ||||||||||

| Strategic planning | ||||||||||

| Human resource management | ||||||||||

| Financial management/audit | ||||||||||

| Other expertise | ||||||||||

| PERSONAL ATTRIBUTES | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| Clear communication skills | ||||||||||

| Leadership competencies | ||||||||||

| Strategic agility | ||||||||||

| Political astuteness | ||||||||||

| OTHER ATTRIBUTES | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| Proactiveness | ||||||||||

| Clear moral or ethical boundaries | ||||||||||

| Credible as independent voice | ||||||||||

| Honesty | ||||||||||

| Directness | ||||||||||

| Ability to challenge | ||||||||||

| Embracing ambiguity and coping effectively with change | ||||||||||

| Ability to present the truth in helpful ways | ||||||||||

| Network of contacts | ||||||||||

Notes

- 1 See, for example, Terjesen, S., R. Sealy, and V. Singh (2009). Women directors on corporate boards: a review and research agenda. Corporate Governance: An International Review 17(3): 320–337. There is of course a large literature on the topic.

- 2 This very useful process for determining board focus is adapted from Paul Strebel (2004). The Case for Contingent Governance, Sloan Management Review, MIT.