CHAPTER 23

Effective Diversity

Diversity is Good … But Why; and When?

The assertion that diversity is good has become a mantra in business. Many studies demonstrate the advantages of diversity for companies in search of new ideas, observations, strategic directions, and competitive advantage. Organisations may derive tangible task-related benefits from diversity, because having a variety of expertise enables a firm to assign each part of a task to people with the relevant knowledge. Diversity also has innovation-driving benefits, because people with different perspectives see things differently. This can lead to creativity and a questioning of assumptions, and ultimately to new synergies.

However, diversity also comes with downsides, because it raises barriers to alignment. These include communication-related barriers. People's different frames of reference mean that words and actions can have very different significance: this makes communication less efficient and can lead to conflict that may be difficult to resolve. Other barriers arising from greater diversity are related to identity and trust: we find it harder to identify with and deeply trust people who are different from us.

When there is a strong need for innovation, and shareholders represent divergent views, diversity is a key strategic advantage. But the situation is different when there is a single shareholder with a clear view of what needs to be accomplished, and when the need for innovation is limited – for example, where a private-equity firm has taken ownership of a company and is seeking to turn it around. In that case, board diversity can lead to time being wasted on conflict and difficult communication, detracting from the discipline required.

Figure 23.1 Diversity at the Board Level

In order to tap fully into the benefits of diversity, boards need to manage this process well. That itself calls for a significant investment of energy and time and requires a dedicated and skilled chair. Ultimately, diversity is a choice (see Figure 23.1).

Diversity as a Considered Choice

In previous decades, when corporations did choose to become more diverse, it was as a result of a powerful external push – and in many cases, a jolt delivered by momentous, structural changes in the marketplace. One such milestone came about in the 1990s, when a number of US multinationals started generating more than 50% of their revenue from international markets. Suddenly, the user of their products in the US Midwest was no longer their typical customer. Predictably, this gave rise to widespread interest in understanding, communicating with, and marketing to other countries.

Today, it has become mainstream to say that a board's composition should more closely resemble the make-up of the company's stakeholders. This entails having directors with diverse objectives, social and economic agendas, communication channels, and preferred technologies. In this chapter, we focus on five dimensions of diversity – gender, culture, personality, age, and social background – and look at how a strong chair can manage these to make a board more effective.

Gender

The debates regarding gender balance in the boardroom have zoomed in on many of the obstacles to understanding and practising diversity and have brought several questions to the fore. Should boards of directors as well as C-suites strive to fulfil self-imposed gender quotas? And are certain types of societies better predisposed to opening the boardroom to greater numbers of female directors?

In many societies around the world, women are still in the process of entering the workforce in more substantial numbers – a key long-term prerequisite for their assuming corporate leadership positions. In addition, research has suggested that diversity, including gender diversity, has been shown to produce more pronounced positive effects in countries with stronger shareholder protection1 – because this motivates the board to draw on the diverse knowledge, experience, and values of each director.

Much effort has been made in academia, the media, and elsewhere to correlate female representation on boards with companies' financial, operational, or strategic performance. This constitutes a laudable attempt to identify a ‘selling point’ for advocating more female directors, although the findings so far have been mixed.

In a 2015 MSCI study, companies with at least three female board members outperformed others in overall returns on equity by an average of 36%. A similar study in 2018 by MSCI showed that companies with diverse boards (three plus female directors over three years) and leading talent management practices experienced growth in employee productivity that averaged 1.2 percentage points above their industry medians. This growth rate exceeded that for firms with just a diverse board and for firms with only strong talent management.2

Such findings have led more institutions to view gender diversity as a yardstick for making investment decisions. For instance, a number of asset management firms have launched funds which invest specifically in companies showing high levels of gender diversity on boards and in senior leadership. One such investment fund is the Street Global Advisors' Gender Diversity Index ETF, which was launched in March 2016 and seeded with an initial $250 million from the California State Teachers' Retirement System (CalSTRS).3

More fundamentally, however, boards should challenge the validity of the underlying research question. It is truly necessary to place a burden of proof on female executives and proponents of greater gender diversity? Is a greater female presence on boards only desirable if it comes with a guarantee of demonstrable and consistent improvements in a company's quantitative indicators? Do women need to be ‘better than men’ before they gain more equitable representation in the boardroom?

The business community must revisit these simple yet deep-seated issues with more clarity and integrity if it is committed to long-term improvements in corporate governance. It is also possible that gender diversity creates different distributions of performance (for example, by truncating downside risks on large transactions or integrity issues) rather than levels of performance.

Culture

The growing diversity of nationalities represented on corporate boards has likewise posed complex questions and raised practical obstacles to boards' long-term performance, as well as to day-to-day operations. What is obvious is that for all the incessant talk of globalisation, a truly global culture remains conspicuous by its absence.

To develop an understanding of other cultures, we need to be able to examine our own. The tricky thing about culture is that it is very much the software running through the human brain – and, much like real software, it is invisible (see Figure 23.2). At an individual level, culture is about mental programming and conditioning, the bulk of which takes place in childhood and school. This early-life process leaves every individual with a set of fundamental assumptions about themselves, others and the world. According to cross-cultural communication studies pioneer Edward Hall:

Culture hides much more than it reveals, and strangely enough what it hides, it hides most effectively from its own participants. Years of study have convinced me that the real job is not to understand foreign culture but to understand our own. I am also convinced that all that one ever gets from studying foreign culture is a token understanding. [To study another culture] is to learn more about how one's own system works.4

At a minimum, the opportunity to learn about one's own cultural profile, habits, and emotional triggers will strengthen one's confidence and boost self-acceptance. Crucially, this teaches us that others may be very different in terms of their cultural backgrounds – and that is okay.

Figure 23.2 Cultural Iceberg.

Source: Based on data from Stanley N. Herman, TRW Systems Group 1970

Personality

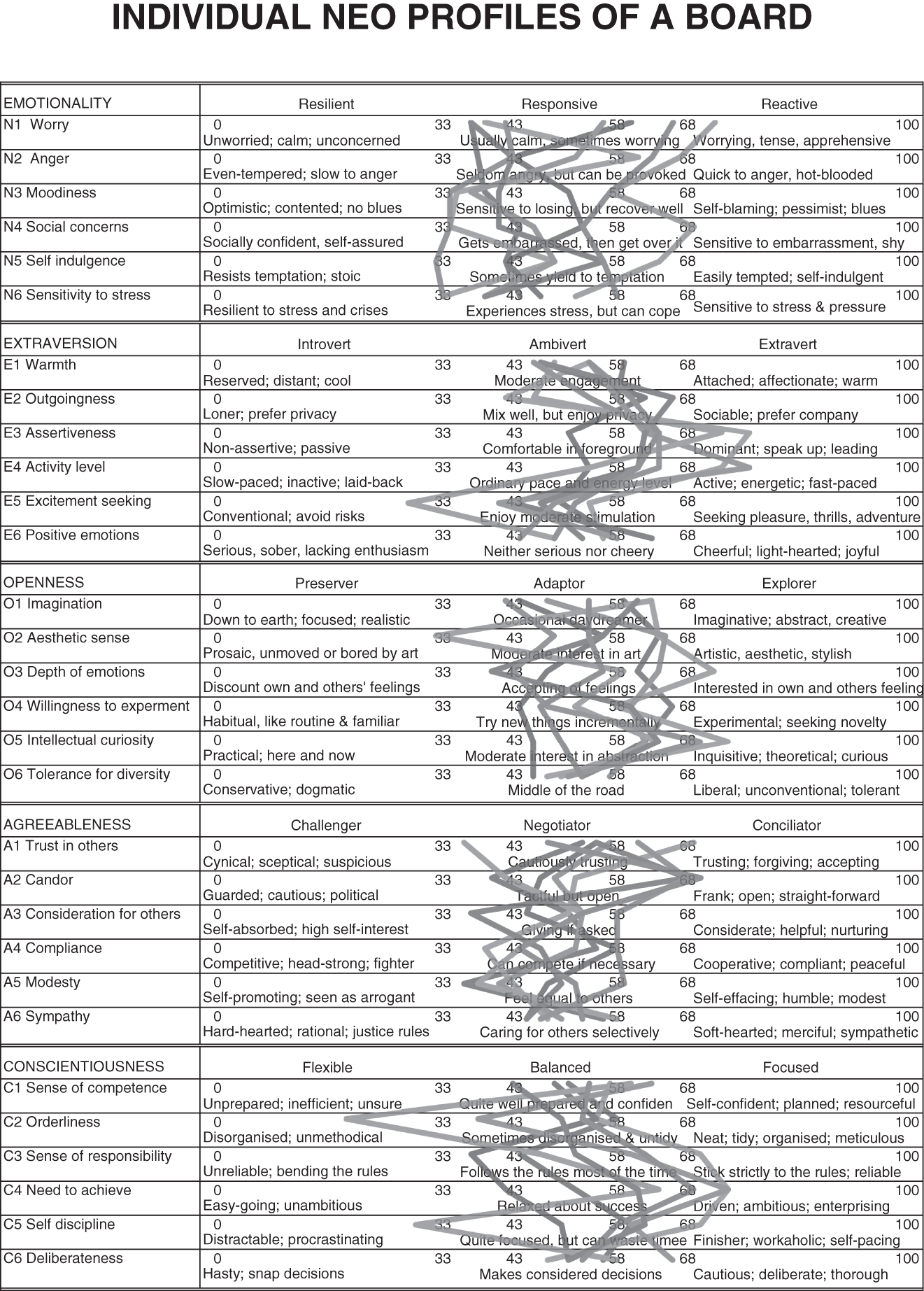

Personality is an important aspect of diversity. While there are many ways to differentiate between personalities, one increasingly popular theory is the Big 5, according to which there are five different dimensions of personality. The NEO PI-R, for example, is gaining acceptance as a personality tool. It defines the five big dimensions as being emotionality, extroversion vs. introversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness; each of these five dimensions has six subdimensions or facets. (For a more detailed description of the NEO PI-R, see Chapter 7.)

Diverse personalities can bring great benefit to the boardroom by stimulating debate and challenging perspectives. However, because this is a less obvious element of group diversity, it can sometimes be poorly managed and become dysfunctional. Often, too, diversity of personality is uncomfortable and therefore unconsciously resisted. Some personality dimensions might even result in the emergence of an in-group. For example, if the chair is fast-paced in meetings, he or she might become highly impatient with directors who are more methodical. And at lunch, the chair may unconsciously choose to sit next to someone who resembles them on this dimension, thereby becoming closer to that person and building up trust. It is therefore particularly important that the chair is aware of personality differences and the challenges these may present in boardroom discussion.

Figure 23.3 below shows a board mapping of personalities. The CEO (an Italian from Sicily) had a high score on the emotionality dimension, while the British chair was at the other end of the spectrum. While both were high-performing individuals, this difference created difficulties in communication that had become excruciating. When well managed, the combination of a resilient chair and a sensitive CEO can be wonderful: the heightened sensitivity of the CEO helps the organisation tackle challenges and threats, while the chair offers a safe psychological base. But when poorly managed, that combination becomes a threat to the organisation.

Age

Age diversity has become increasingly important for boards in the context of innovation. The demands put forward by innovation – particularly the need to think about and anticipate trends in the market – require boards to display diversity of thinking and have the right mix of directors who will make innovation part of every board discussion.

The business risk of not understanding innovation has become more acute than ever. Toyota, for example, made changes to its organisational structure, including its boardroom, in both 2016 and 2017. It cited the need for quick judgement, decisions, and action through genchi genbutsu (onsite learning and problem-solving), because ‘the changes the company faces require a different way to think and act’.

Figure 23.3 Individual NEO Profiles of a Board

As boards recognise the need to accelerate innovation, they have also been more receptive to appointments of young members whose background may greatly expand the board's collective experience and expertise. One of the board members at private Swiss bank Vontobel, Björn Wettergren (born 1981) is an engineer MBA and founding family member whose previous roles spanned banking, venture capital, and human resources. This illustrates the bank's commitment to adjusting its board structure as digital technologies – the cloud, robotics, advanced analytics, cognitive computing, and artificial intelligence – reshape its service delivery.

Social Background

Social background is another critical dimension of diversity. The 2016 Brexit referendum in the United Kingdom highlighted longstanding tensions and distrust between ‘big business’ and employees. As part of her campaign to become Prime Minister, Theresa May revisited the theme of workers playing a larger role in the boardroom, as a way of overcoming the legacy of boards reproducing the same elite, narrowly defined social and professional circles. May suggested it was time for employees to have more input in the way businesses are run.5

The experience of Northern European, particularly Scandinavian, economies that placed employee representatives on boards as far back as the 1970s shows that this is a long-term project that requires a cultural change to be successful. Shifts in the power balance – and the ensuing power struggles – are inevitable. So are issues of confidentiality, because sensitive information may easily be channelled to the workforce. And like in the early days of any diversity initiative, there is always the risk of going through the motions by appointing token representatives whose voices may or may not be heard.

Having directors with diverse social backgrounds is helpful for ensuring a wide range of viewpoints (and therefore for preventing blindspots). But if this diversity is not well managed, it may result in tensions that can lead to governance failures – as in the case of Hull House.

We Have Embraced Diversity … Now What?

At a practical level, board members will develop a deep appreciation of how to capitalise on their team's diversity. In particular, they will learn to understand the strengths that reside in individual directors' competencies, and how these can transfer, multiply, and inform new areas of the organisation's activities and competitiveness. For example, many companies that expanded into central and eastern Europe during the 1990s later built on this experience and their newly acquired skillsets by formulating an expansion strategy for the Asia-Pacific region in the 2000s. In doing so, they drew on their executives' knowledge and expertise gained in emerging markets, and internalised it as a powerful differentiating factor in the company's future strategy.

In the long run, pursuing diversity becomes a journey and a learning process. As on all journeys, companies and organisations that are overseen by inspired, visionary boards will not hesitate to take risks, adopt contrarian approaches, and push the envelope. They will challenge and redefine existing narratives of diversity by creating new role models; nurturing diverse talent through mentoring programmes; and pursuing alternative paths to excellence in diversity. Much of this will entail deep thinking about what the source of the company's competitive advantage will be in ten years' time.

Well-defined objectives and outcomes are a crucial element of any organisational effort aimed at strengthening commitment to diversity and then managing that diversity effectively. Board members must be able to show, rather than just feel, their new outlook on diversity – whether it relates to gender, culture, or other attributes. Their knowledge must translate into a skill set, and the behaviour that this drives should become automatic and take the form of a habit. From there on, board members and executives should be able to measure their progress and growth toward excellence.

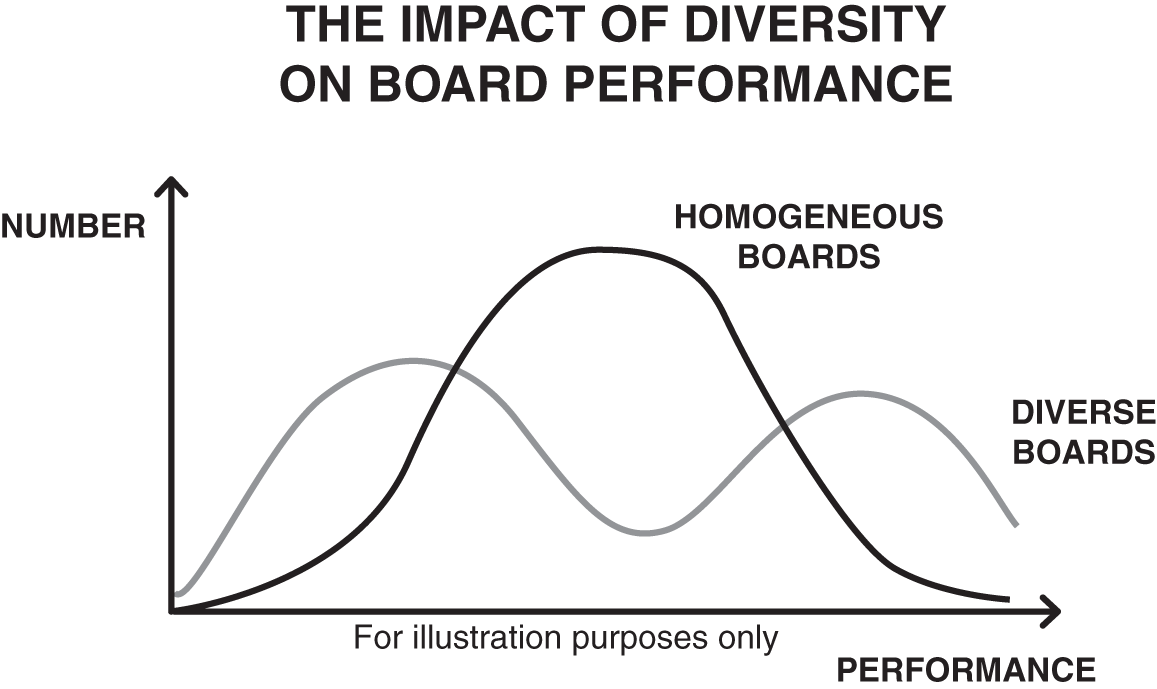

They say a little knowledge is a dangerous thing, and the same is true of diversity. Many boards have succumbed to the temptation of approaching diversity in a mechanical way – by checking boxes, or filling stated as well as unstated quotas. True, even going through the motions like this may be better than doing nothing, as it may at least produce modest results. But as copious research has shown, diversity can only be a powerful predictor of a company's performance when it is understood and managed well. Boards that are superficially diverse but have failed to address, reflect on, and mobilise that quality will soon face issues of miscommunication and resentment as directors report overwhelming feelings of being ‘thrown together’. In this scenario, diversity turns into a liability as the board underperforms ‘normal’ homogeneous teams by a wide margin (see Figure 23.4).

Figure 23.4 The Impact of Diversity on Board Performance.

Source: Adapted from J.J. DiStefano and M.L. Maznevski: Creating value with diverse teams in global management. Organizational Dynamics, Vol. 29, No 1; and research by C. Kovachu.

The Chair's Role in Building and Nurturing Diversity

It is a recurring theme in this book that the chair has an important role to play – and the task of integrating diverse board members into a high performing team is no exception. The board chair leads the way in embracing inclusiveness and diversity. He or she is conscious of the need to do more than just respond to demographic trends in the outside world.

To start with, models of building consensus are largely determined by culture. According to Lewis,6 the American style of arriving at a consensus can be characterised as structured individualism, as senior and middle managers make individual decisions. UK directors are likely to be more comfortable with casual leadership, while Scandinavian executives will fall back on the principle of primus inter pares – in other words, ‘the boss is in the circle’. Depending on their cultural make-up, boards in other countries may lean toward autocratic, top-down styles or a combination of hierarchy with group agreement. Once consensus has been built, the question of who is accountable arises. In some cultures, it is the individual manager; in others, it is the boss. In Asia, one could argue that the entire team is collectively accountable.

Leadership styles are strongly defined by culture too. Depending on the particular cultural context, leaders may demonstrate and look for technical competence; place facts before sentiments, and logic before emotion; and be deal oriented, with a view to immediate achievements and results. Alternatively, they may choose to rely on their eloquence and ability to persuade; inspire through force of personality; and complete human transactions emotionally. Or they will dominate with knowledge, patience, and quiet control; display modesty and courtesy; and create a harmonious if paternalistic atmosphere for teamwork.

Boards can only bridge differences if they understand what these are. Building diversity is an ongoing process whereby collectives create their own world of meaning, and where directors integrate new meanings and add new dimensions to themselves. Ultimately, they learn about themselves and about the need to understand others, recognise the inherent contradictions, and learn to embrace other people's realities.

Chairs can do a lot of good work in this area – not only in educating the board, but also in setting the tone for management and the entire organisation. The company should visibly advance from aspiring to diversity awareness to achieving and disseminating sensitivity, understanding, and knowledge. Once these become widespread, the organisation and the board may be truly able to celebrate diversity as a key part of their identity and achievement.

A board chair who is committed to growing diversity in the organisation will encourage others to understand very clearly who they are; to recognise the ‘spectacles’ or filters that colour their perceptions; and to seek common ground in all situations. Board members will learn to switch their cultural gear in order to improve interaction. And as they invest time and patience into building trust across a diverse board, they will take differences in decision-making into account.

Many types of exercises help bring a board with a diversity of perspectives towards more shared views. This helps build constructive dissent, which is itself at the heart of good governance. For example, one we use is the board history exercise. Board members are encouraged to share (and draw!) their experience of the most significant moments in their tenure at the company. This allows to build a common view of the past based on diversity of understandings, which by itself helps reconcile views to the future.

Diversity brings specific expertise to a board, as well as increased potential for innovation. Poorly managed diversity, however, can be disruptive by hindering communication and eroding mutual trust. A strong board will thus develop processes to manage diversity well. Even well-established boards should have a systematic board composition oversight, with regular assessment of required capabilities (from expertise to familiarity) and a current composition matrix. And as we will see in the next chapter, boards also need to have a detailed overview of the organisation's executive talent pipeline.

Notes

- 1 Post, C. and K. Byron (2014). Women on boards and firm financial performance: a meta-analysis. Academy of Management Journal 58(5): 1546–1571.

- 2 https://www.msci.com/documents/10199/4bd5f3bb-e5a4-4993-9c2a-4b44423ba4a2.

- 3 www.businesswire.com/news/home/20160307005890/en/State-Street-Global-Advisors-Launches-Gender-Diversity.

- 4 Hall, E. (1959). The Silent Language. DoubleDay.

- 5 http://recruiter.e4s.co.uk/2016/08/01/employees-boardroom/.

- 6 Lewis, R.D. (1996). When Cultures Collide. Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

The exercise starts by a short individual talks, in which board members identify their personal views, before engaging smaller groups (say three or four) into a group task which brings these views together. Individual Task Identify the three most significant events that happened in your company for your time period. Restrict your choice of events to those events that hold significance for your company today and continue to influence the company:

Group Task

The exercise closes by a presentation of the different posters/pictures. These can become part of board folklore … |