8. Maintaining a Personal Design Playground

THERE’S A WORLD WHERE I CAN GO AND TELL MY SECRETS TO

IN MY ROOM, IN MY ROOM

IN THIS WORLD I LOCK OUT ALL MY WORRIES AND MY FEARS

IN MY ROOM, IN MY ROOM

DO MY DREAMING AND MY SCHEMING

LIE AWAKE AND PRAY

DO MY CRYING AND MY SIGHING

LAUGH AT YESTERDAY

NOW IT’S DARK AND I’M ALONE BUT I WON’T BE AFRAID

IN MY ROOM, IN MY ROOM

—THE BEACH BOYS

One of my mantras has always been: “Everybody needs a place to fail.” One day I will get around to making the bumper sticker. I’m not advocating failure in and of itself. I’m talking about having a pressure-free environment that encourages free play and daring experimentation without fear of failure. In country music songwriting, there is a fine line between the sublime and the sappy. The trick is to get as close to that line as you can without crossing over. You have to risk sappiness to achieve sublimity. The same may be said of great design. You have to risk failure to achieve success.

When I say, “fail,” I don’t mean that you should sabotage yourself intentionally every time you design (although that might be an interesting experiment). I simply mean you should blatantly risk failure, which will inevitably mean some actual failure. Now obviously you don’t want to fail on a client project. Everybody needs a place to fail, but that’s not it. One way to keep commercial failure at bay is by allowing yourself ongoing room to fail in a less risky context.

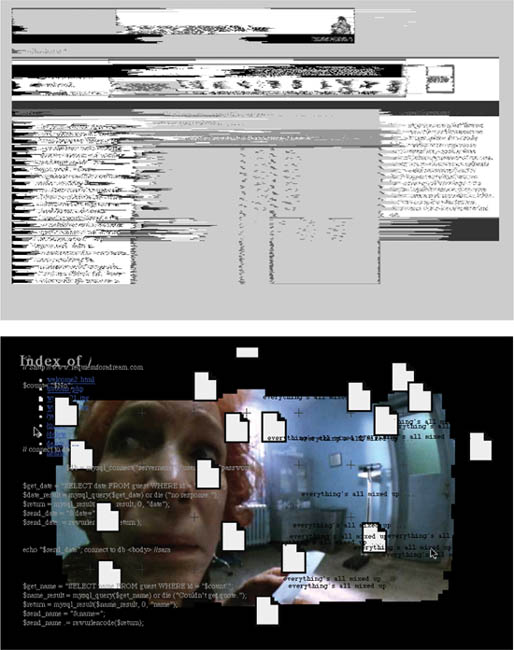

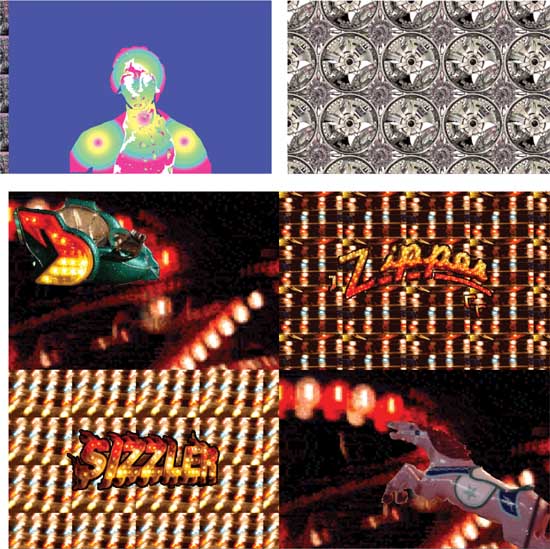

Playdamage.org experiments with low-resolution animation and subjective narrative. Everybody needs a place to fail, and this is mine.

Randy Nelson, head of Pixar University, approaches creativity at the animation studio’s internal training program as “a team sport” by having Pixar’s animators go through sketching and brainstorming exercises in groups to overcome their fear of public failure. He says, “You have to honor failure, because failure is the negative space around success.” Think about it this way: Failure is the “rough”—or the minefield—in which the “diamond” of successful design hides. If you’re unwilling to venture into that field, you will settle for passable, safe, mediocre design. You may never flub it, but you’ll never nail it either.

FAILING PUBLICLY WILL GIVE YOUR EXPERIMENTAL PROCESS AN ELEMENT OF EXCITEMENT AND ACCOUNTABILITY THAT MORE ACCURATELY MIRRORS “REAL WORLD” DESIGN, BUT WITHOUT THE PRESSURE OF DEADLINES AND CLIENTS.

Or think about it like this: Ideas are like cafeteria plates stacked up in one of those spring-loaded dispensers. When you take the top plate, the next one rises up. One of the plates in that pile is your best visual idea, but it may be buried 20 plates down. The only way to get it to surface is to “use up” the 19 plates above it. A personal design playground is the perfect place to use up those top 19 plates.

Your playground should probably be a Web site, whether or not you do new media work professionally. For instance, if you do print work, it’s logistically easier to save your files as high-resolution GIFs or JPEGs and post them online than it is to print out posters and put them up around town weekly. Video work becomes a bit more troublesome online due to bandwidth restrictions, but it’s still possible at short lengths and low resolutions.

Since 2000, playdamage.org has been my personal place to fail. I began it as a way to experiment with unorthodox DHTML tricks, and I still keep adding to it years later because there are creative things I want to explore that simply can’t be explored in any other forum.

Playground Rules

Now that you understand what I mean by “failure,” you may want to follow some of these suggestions for how to get the most out of your personal design playground:

Fail publicly. It’s not enough to merely fail in a charcoal sketchbook hidden in your bottom drawer. You need to fail in your actual professional medium—Web, print, video, whatever—and you need to fail publicly. There is a freeing, confidence-building, inhibition-destroying strength that only public risk taking can produce.

Failing publicly will give your experimental process an element of excitement and accountability that more accurately mirrors “real world” design, but without the pressure of deadlines and clients.

Fail at the medium in which you hope to improve. If you want to improve your Adobe Photoshop skills, work in Photoshop and export your finished experiments as image files. If you want to improve your Macromedia Flash skills, work in Flash and export your experiments as SWF files. By all means, feel free to keep a personal sketchbook in addition to your playground. Regular sketching keeps your hand and eye in practice, and even if you’re not an illustrator by trade, sketching can’t help but improve your design work. But a playground is something beyond a sketchbook, something more polished and closer to finished. Take each playground piece to full completion, or at least make it complete enough to upload for someone to see. Going beyond the thumbnail/sketchbook phase of design on a regular basis in an experimental way makes you that much more confident to risk greatness on your next commercial mock-ups.

DON’T TRY TO SIMULATE COMMERCIAL PROJECTS OR COMMERCIAL CONSTRAINTS. WORK WITH CONTENT THAT INTERESTS YOU PERSONALLY. IT’S A PLAYGROUND, NOT A WORK CAMP.

The Yancey Tire Chapel in Sawyerville, Alabama is a quintessential example of low-budget, experimental architecture. Student architects Steven Durden, Thomas Tretheway, and Ruard Veltman of Auburn University’s Rural Studio constructed this striking chapel out of recycled tires, salvaged beams, tin, and rocks from a nearby river.

Even architects can risk failure in their actual 3D medium without having to acquire a large commercial building contract. In Alabama, visionary architect Sam Mockbee pioneered a program at Auburn University’s Rural Studio that allows students to design and construct ingeniously efficient, low-cost structures that meet the practical needs of the surrounding rural community. Architect David Baird regularly takes his Louisiana State University architecture students to a squatter settlement in the border town of Renosa, Mexico, to build improved housing out of concrete, tin cans, and found materials. These projects are more than just mere design playgrounds. They are providing real solutions to challenging social problems. Still, if nothing else, architects can build tree houses, doghouses, or even (appropriately enough) actual playgrounds. As long as the experimentation extends beyond mere blueprints and into 3D space.

Fail anonymously. Remember, this is not your online portfolio. There shouldn’t even be a link from your online portfolio. If you can afford to, choose a completely different URL for your playground. If you’re extremely paranoid—or just for fun—register your domain name under a pseudonym. Design technologist Joshua Davis maintains www.once-upon-a-forest.com in the persona of a mysterious artist named Maruto. He’s not paranoid; it’s just for fun, to explore experimental design work he wouldn’t otherwise explore in his everyday persona. You don’t have to create an alter ego in order to maintain a design playground, but keeping your playground separate from your commercial portfolio will encourage you to risk more and fear less.

Fail early. Don’t wait until your skills are more polished before you start or you’ll never start. There’s an old hymn that says, “If you tarry ’till you’re better / you will never come at all.” Come as you are and start there. Your playground isn’t the opening night of a ballet; it’s more like rehearsal.

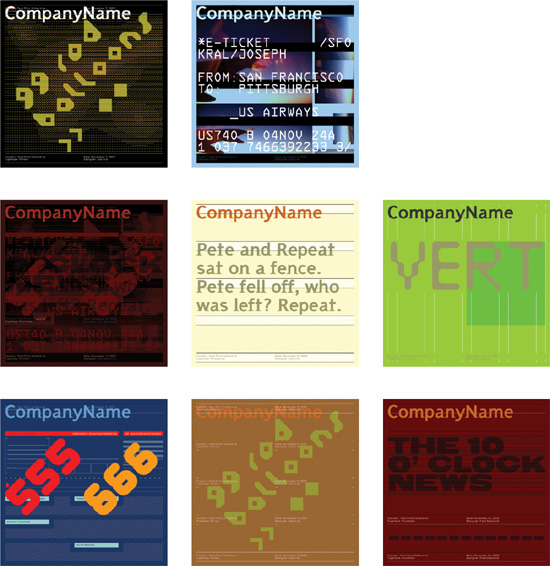

In these testpilotcollective.com splash pages from November 4 to13, 2003, the same basic layout is explored using a variety of typefaces, type sizes, textures, layout directions, and color schemes. The goal is not the production of a masterpiece but the growth of the designers.

EXPLORING WHAT DOESN’T WORK CAN BRING YOU ONE STEP CLOSER TO WHAT DOES WORK. BESIDES ALL THAT, SOMETIMES IT’S SIMPLY FUN AND CATHARTIC TO DO THINGS “THE WRONG WAY.”

Fail often. Update your playground as regularly as opportunity allows. For more than five years, the three designers at testpilotcollective.com put up a new splash page for their digital typography Web site every day. That’s over 1,825 separate designs. Don’t wait until you come up with work that blows people away. This is not a polished portfolio; it’s an ongoing experimental design laboratory. Former Disney imagineer and brainstorming guru C. McNair Wilson says the best way to have one good idea is to have 300 ideas. Self-censoring and editing can come later. Create first, and create a lot.

Fail compulsively. Now is the time to explore specific design avenues exhaustively. Is there any way to make Times New Roman look fresh and sexy? Are you any good at hand illustration? How about vector illustration? How about animation? Get on a particular design track and run it into the ground. Graphic designer S. Bradley Askew is infamous for exhaustive experimentation with the same color schemes and typefaces at www.hellmedia.com. After the twentieth screen of yellow and baby blue, I’m personally ready to move on. But it’s not about me as the visitor. It’s about the designer’s personal explorations.

If a certain design approach keeps yielding fruit, you know you’re onto something. Keep tweaking it. If another design approach fizzles out and dead-ends, that’s one less path you’ll have to head down only to discover that it doesn’t work. Later, in a commercial setting with a tight deadline, knowing what not to try can be half the battle.

Fail with fun content. Don’t try to simulate commercial projects or commercial constraints. Work with content that interests you personally. It’s a playground, not a work camp. Some designers might even be tempted to think of their playground as “art.” It may well be art (depending on how you define art), but art comes with its own sets of expectations and pressures. It might be safer not to call it much of anything at all. “Media experimentation locale” will do in a pinch.

Fail ephemerally. Don’t feel obliged to archive your playground work. When Mike Cina began www.trueistrue.com, he completely replaced each piece with a new one. As a visitor, if you didn’t want to miss a piece, you had to visit regularly because there was no index of previous works. Of course, Cina was archiving all these pieces on his hard drive and they were later released on a CD-ROM. The point is, it’s the process that’s most important, not any single finished piece of work.

An alternative method is to work series by series. Each new series marks a new exploration. Leave your work online until you have finished with that series and then remove it to begin a new series. Or you can leave all your work online and archive it according to series.

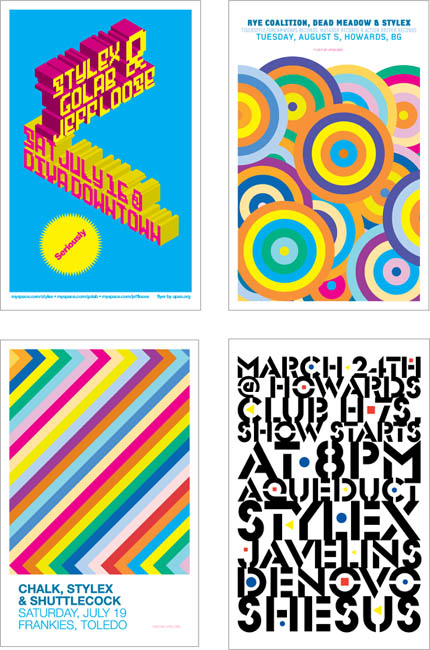

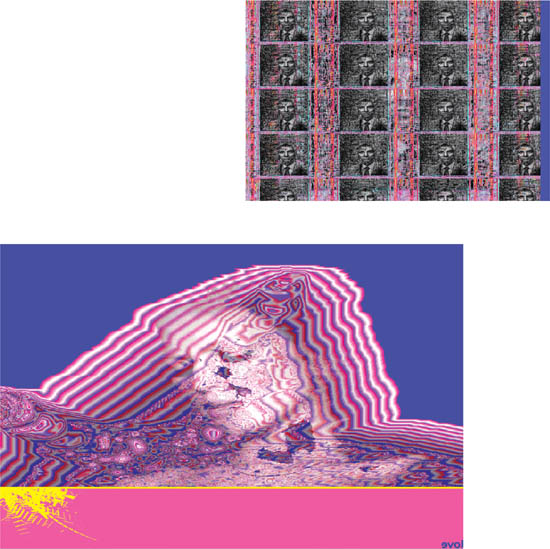

Designs that compulsively explore a Day-Glo dead-end from S. Bradley Askew’s playground, www.hellmedia.com. If Askew can make this color scheme work, imagine what he could pull off in a nice burgundy and teal.

Mike Cina’s www.trueistrue.com circa 2002 is an elegant example of an unapologetically cryptic interface. Clicking on a color swatch triggers a unique animation that overwrites the entire grid. There are over 14,000 possible combinations, all of them counterintuitive.

Fail cryptically. Your playground is not obliged to make sense. Some interactive designers use their playgrounds to experiment with anti-navigation, intentionally attempting to disorient their visitors. Exploring what doesn’t work can bring you one step closer to what does work. Besides all that, sometimes it’s simply fun and cathartic to do things “the wrong way.” Your playground is a place to get such horseplay out of—or into—your system.

Fail unobligatedly. Don’t let your playground become a burden or a drain. That takes the “play” out of it and defeats the whole purpose. If it gets old, take a break from it. Avoid imposing regular update schedules on yourself unless regular experimentation is one of your self-improvement goals. Set your online playground up so that it’s easy to update. Many online design playgrounds are simply a series of image files linked one to another in reverse chronological order. Simply put up the new image and link it to the last one. Don’t kill yourself worrying about usability or accessibility. Remember: This is not commercial work; it’s more like personal design therapy.

Archive success. If any experiments happen to succeed, feel free to save those pieces and link to them from your commercial portfolio. You might want to create a special section for them called “personal experiments.” This can be a way to attract new commercial work that is more experimental and may be more “up your alley” than other work in your commercial portfolio. Just don’t let your playground become a portfolio-building tool, or you’ll defeat its purpose. Any successes should be seen as happy accidents. And if no smashing successes ever materialize, no worries. It’s a playground. Keep playing.

ONGOING PLAYGROUND EXPERIMENTATION KEEPS YOUR DESIGN WORK FROM BECOMING TOO STILTED AND FORMULAIC. IT INJECTS YOUR PERSONALITY AND PERSPECTIVE INTO YOUR DESIGN STYLE.

Playground Advantages

With commercial deadlines constantly looming, why waste time on experimental graphic design that doesn’t pay the bills? Because it’s not a waste of time. Think of your design playground as a professional development laboratory, which will eventually result in your ability to pay even more bills! Here are several good reasons to maintain a personal design playground:

Playgrounds instill boldness. Olympic gymnasts practice their routines hundreds of times before performing them in competition. This doesn’t guarantee their competition performances will be flawless, but it does give them the confidence to attack their routines boldly, without fear of falling. It’s true that overconfidence can lead to bad design, but timidity inevitably leads to horrid design.

Playgrounds allow you to amass a catalog of successful design approaches. None of your playground work will be perfectly suitable for commercial design in and of itself, but some of the techniques you’ve explored will be readily adaptable to various commercial projects. And they will be your techniques, not someone else’s. You will own them. You will be comfortable implementing them on commercial projects because you will have already explored them compulsively in the safety of your own playground.

Playgrounds allow you to develop and advance your own design style. It takes a combination of experimental lab work (playground tweaking) and actual field experience (commercial work) to develop as a great designer. Ongoing playground experimentation keeps your design work from becoming too stilted and formulaic. It injects your personality and perspective into your design style. This is as it should be.

Playgrounds also allow you to track your growth as a designer. Flipping back through your playground work over the years is a helpful means of self-assessment. If you observe yourself falling back on the same obvious solutions, you can challenge yourself to explore new directions.

Playgrounds allow you to receive critical feedback from the online design community. Once you’ve put up a decent amount of work at your playground, submit its URL to an online design community site. (Several sites are listed in the back of this book.) Then somewhere on your playground, include an e-mail link so visitors can send you feedback. The feedback may be encouraging, discouraging, banal, instructive, or just plain ridiculous. The point is that you’re getting free feedback from people other than your coworkers and clients, and they’re commenting on experimental work that you may never show to your coworkers or clients. Of course, take it all with a grain of salt; not everyone with an Internet connection is a competent design critic. Take what you can use and leave the rest.

DESIGNER MILTON GLASER SAID, “PROFESSIONALISM AS A LIFETIME ASPIRATION IS A LIMITED GOAL.” DESIGN PLAYGROUNDS ARE VEHICLES TO HELP YOU MOVE BEYOND MERE PROFESSIONAL COMPETENCE AND ON TO SOMETHING GREATER.

Playgrounds can lead to interesting commercial work. The London-based design firm Hi-Res began its new media career with an online playground called soulbath.com. That experimental playground site landed Hi-Res a gig to design the even more experimental movie promotion site www.requiemforadream.com, and it’s been a successful commercial ride ever since. Hi-Res designers started off doing the kind of experimental work they enjoyed, and that attracted the kind of commercial work they enjoyed. Of course, Hi-Res also happens to be a group of absolutely brilliant new media designers, and not every playground leads to a gig with Artisan Entertainment, but it could happen.

Playgrounds keep you passionate about design. Some people are reading this thinking, “I work all day in Illustrator; the last thing I want to do when I get off work is come home and open up Illustrator.” But playground design is an entirely different animal because you’re in complete control. It can inspire you to remember why you got into design in the first place, which can inspire you to push your commercial projects beyond merely competent because you can’t wait to get back to work and try out the new design approach you just discovered over the weekend. Ultimately, the reclamation of your professional passion and purpose is worth the extra time.

In a 2001 talk at an AIGA conference in London, designer Milton Glaser made this bold statement: “What is required in our field, more than anything else, is the continuous transgression. Professionalism does not allow for that because transgression has to encompass the possibility of failure and if you are professional your instinct is not to fail, it is to repeat success. So professionalism as a lifetime aspiration is a limited goal.” Design playgrounds are vehicles to help you move beyond mere professional competence and on to something greater.

Hi-Res built an experimental playground at www.soulbath.com, which eventually led to commercial work designing www.requiemforadream.com. Both sites employ intentionally disorienting Flash interfaces to compelling narrative effect.

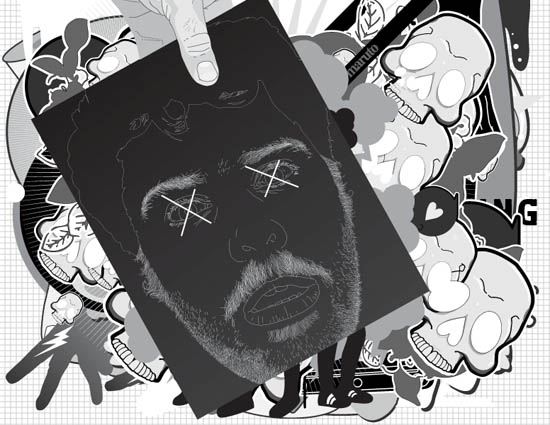

Dustin Hostetler’s upsod.com is a playground of experimental illustration in which faces, hands, and skulls figure prominently. The face and hands are his. I’m not sure about the skull.

Playground Interview: Dustin Hostetler of upsod.com

Dustin Hostetler is an illustrator and graphic designer who has maintained a personal design playground at upsod.com since 2000. Upsod stands for United Planets Space Organization Diary (in case that wasn’t immediately apparent). www.Upsod.com is arranged in batches of 50 illustrations. When Hostetler reaches 50 illustrations, he archives those 50 and begins a new batch. The illustrations range from figurative to abstract, with an inordinate emphasis on hands, faces, and skulls. I asked him about his playground and the influence it has on his commercial work.

Upsod History and Practice

Why did you start upsod.com?

Sometime during 2000 I realized I needed a Web site. I had just been to Flashforward [a Macromedia-sponsored Web design conference] and was totally blown away by all these really dynamic personal Web sites. It was a scene I immediately wanted to be a part of, but since I had zero Web experience, I needed to make something that was easy for me.

At first the site was housed at a secret address only my friends knew about. I was the first person any of my friends knew who had a Web site, so every day I would make a small group of people (including my mom) new things to look at.

I updated it quite frequently, and if I didn’t keep up with it people would e-mail me and ask, “What’s up?” Even though these people were just my close buddies, it really motivated me to keep updating. My audience was small but dedicated, and it got me excited about producing work on the computer. I had only gone into design because art school was uninspiring, but realizing I could make art on the computer was a real life-changing moment.

Currently, who is your intended audience?

I don’t really have an intended audience. I put up a lot of work that I’m not very proud of or happy with. Then I get motivated to put up something better so that a first-time viewer won’t see a shitty image on the front page. In that way, I am my own audience because if I’m not happy with what I have up, I make more work.

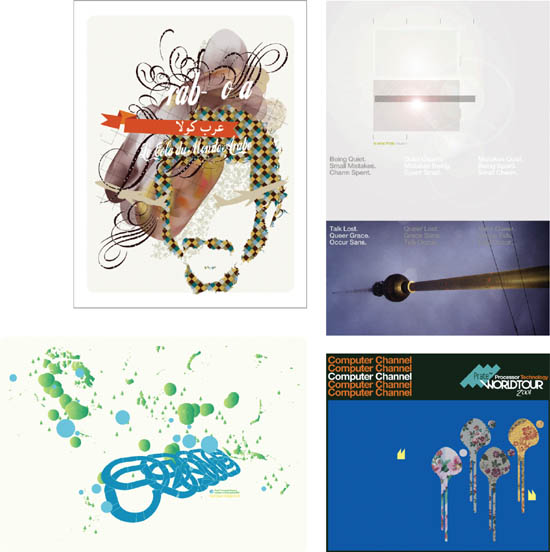

Dustin Hostetler: Poster design informed by experimental work at upsod.com. Playground work may not be overtly practical, but it positively affects your practical design skills.

A lot of the pages have become inspiration for other projects, like my band’s CD covers. In that way, my friends are also my audience because they can visit my archives and say, “Can we make our poster or cover look like this page?”

Does upsod.com have a regular production schedule?

Initially I told myself I would update it daily. Of course anyone who tries something like this knows it’s very difficult to keep up with. As the versions have progressed, I’ve deemphasized the frequency of updates and focused on the concepts.

As far as breaks between versions of 50, initially I looked forward to the end of each version because I could immediately start thinking about the next. Now I take up to a month off between versions, so I can reapproach each version with a clear head.

How much time do you spend executing each screen?

One hour max.

How do you know when a screen is finished?

When I’m sick of looking at it.

What kind of things do you explore on upsod.com that you can’t explore in a physical sketchbook?

I currently have five notebooks on my desk, filled with to-do lists, doodles, and random phrases. It’s really important to me to put things down “on paper” so I don’t forget any potentially great ideas. But upsod provides me with a vehicle to make immediately archived work. In general, working on the computer allows me to realize my ideas much more quickly than I could in my days of paint and pens.

Do you get ideas for upsod.com beforehand, or is it all exploration from the time you begin working on the computer?

I may scribble a phrase down in my notebook and then come back to it later, but a lot of the work is still created all at once. I plop in front of my computer and just start playing around.

How intentionally thematic is each series of 50 illustrations? Do you set out to pursue certain themes and recurring images?

Sometimes I go into a series with an idea, like all black and white. But I get bored really quickly, and I tire of my own work quickly as well. So even if there is a theme, it seems to fall apart fast. Upsod.com is generally whatever I’ve been exploring at the moment, sort of documented in diary form.

What are some recurring themes throughout the whole site?

The main theme that continues throughout the whole site is me. It really is my diary. Sometimes the images obscurely document serious emotions I’m having, and sometimes not so obscurely. People often tease me for using hands so much, but the thing is, the hands I use are my own. So it is a way for me to bring myself into my work.

Upsod Influence on Commercial Work

What is your day job? Do you consider yourself mainly an illustrator, a designer, an artist, or what?

My day job is creating illustrations for magazines and doing different design projects with my wife, Jemma Hostetler. I consider myself a professional graphic artist. I don’t usually call myself an illustrator because I am self-taught, and I don’t think it is fair to assume I have the talent of someone who has dedicated his life to this profession. I also don’t usually call myself an artist because even though I am trying more and more to get my work into galleries and out of the computer, for the most part I make my living by creating graphics in an artsy sort of way.

Illustrations from upsod.com, Version 9. This particular series explores colors, circles, clustering, and layering.

Has any commercial work come directly from clients seeing upsod?

I don’t think so. I’d like to think at some point I will put something on upsod that will inspire an art director to call me, but I haven’t seen any direct evidence of that happening yet. I tend to steer people toward my online portfolio at upso.org for my “professional” client work, and if they like what they see enough to dig around for more work, upsod isn’t hard to find.

How has doing upsod improved your commercial work? What have you learned about design and illustration from doing it?

Without upsod, I wouldn’t be doing what I do today for a living. Upsod encouraged me to pursue illustration as more than a hobby. It allowed me to create a body of work (as far as style and assets are concerned), and gave me the confidence to create an illustration portfolio site. Upsod has also given me a chance to fail enough times that I tend to fail less for clients. It encourages me to try new things publicly, which has kept me on my toes.

Do you use upsod as a sketchbook for ideas that later turn up in your commercial work?

Yes, I do. When I went to Flashforward in 2000, one of the big things I took away was a comment Joshua Davis made about his site praystation.com. He was publicly giving away code at the time and showcasing a lot of different experiments. He said it wasn’t wasted effort on his part because if a client approached him to work on a project, he may have already created what they needed, and he could basically just sample himself. That really stuck with me.

Will you ever stop doing upsod.com?

I often think about retiring it, but I know I can’t. That site is the reason I am able to do what I do today for a living, and I owe it to the domain to keep it alive and active for as long as I am alive and active.

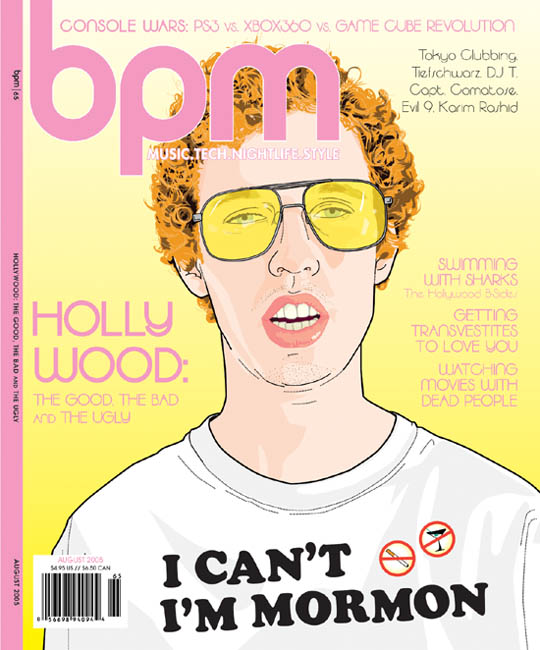

Bpm Magazine cover by Dustin Hostetler. Hostetler has developed a signature illustration style at his playground that is colorful, playful, and particularly suitable to entertainment industry magazines.

Playground Gallery

What does design playground experimentation actually look like? It varies widely from designer to designer, depending on personal interests, visual style, and chosen medium. Some designers experiment almost exclusively with typography. Others experiment with illustration. Others experiment with audio, animation, and programming.

What follows is selected work from four of my favorite playgrounds. I chose these particular pieces not because they are the “best” work ever done by these designers, but because they represent the kind of experimentation that each playground affords.

Mike Cina of trueistrue.com

At www.trueistrue.com, Mike Cina (of the design partnership We Work For Them) has experimented with everything from Flash interaction to homemade book deconstruction, but his specialty is typography. Any phrase at all affords Cina an excuse to get at the heart of the typeface he is exploring. These minimalist studies are beautiful in their restraint and in the asymmetrical balance they achieve using type as pure form.

Jemma Hostetler of prate.com

Jemma Hostetler uses prate.com to explore combinations of texture, layout, typography, and photography in search of original, expressive design styles. Her abstraction of world maps has produced work more akin to conceptual art than to commercial design.

Curt Cloninger of playdamage.org

Playdamage.org experiments with low-resolution animation and short audio loops. Visit the site to see each of these stills in motion with an accompanying mini-soundtrack. The house rules are that no screen can be fatter than 200K. The challenge for me is to generate as much sensory narrative as possible within these limitations.

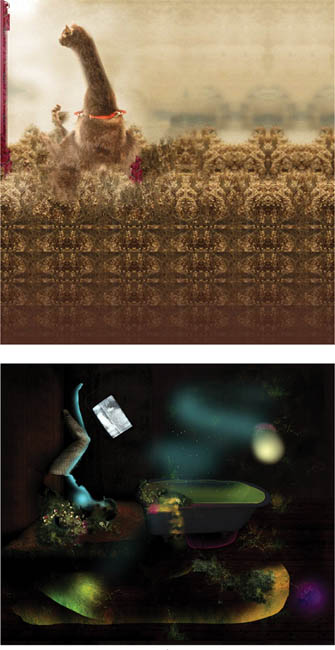

Geoff Lillemon of oculart.com

Geoff Lillemon combines a background in painting with a disturbingly unorthodox Flash animation style to perpetrate the gorgeous hallucination known as oculart.com. If you think these images are haunting in print, visit the site to see them flicker and sway. Oculart feels like a night out with Toulouse-Lautrec on absinthe-soaked mushrooms.

Willful Superfluity

In Civilisation, art historian Kenneth Clark wrote of northern Italian courts of the late fifteenth century: “It’s only in a court that a man may do something extravagant for its own sake, because he wants to, because it seems worth doing... and it is sometimes through such willful, superfluous actions that men discover their powers.” For better or worse, most of us don’t have the finances to provide ourselves with such full-time, courtly leisure. But none of us are so poor that we can’t devote a few occasional hours to practice our own “willful, superfluous actions.”

Personal design playgrounds are safe places of play and experimentation, free from outside censure and nagging self-doubt. Kublai Kahn had his Xanadu, Alice had her Wonderland, Willy Wonka had his chocolate factory, and now you, too, can have your very own playground.org. Because, as Willy Wonka so acutely observed, “We are the music makers, and we are the dreamers of the dreams.” Oscar Hammerstein further elaborated, “You got to have a dream, if you don’t have a dream, how you gonna have a dream come true?”