How can you use your unique engineering strengths to anticipate and overcome obstacles on the way to achieving your goals?

Why Overcoming Obstacles Matters

Many great initiatives and big ambitions start with gusto but fade away somewhere along the road to success. Most of us are familiar with new year’s resolutions. The start of a new year inspires many to think of and define new initiatives, set new goals, and make bold promises: This time it’s going to be different. Most of us are also familiar with what comes next: Somehow we lose momentum, dilute our focus, and quietly give up. At the start of the following year, we will dust up our old ambitions and simply start anew.

This recurring story is not limited to personal goals, but is seen in business as well. A huge corporate initiative takes center stage and is broadly communicated. Top executives line up to declare their support and the organization gets going. However, at a certain point in time, the initiative falters. Here are typical warning signs of imminent failure:

Reverse countdown: What was agenda point number one in every meeting now slowly moves to the number two spot and rapidly slides further down the ladder as time passes.

Hallway lip service: In the beginning, the new initiative is boldly brought up in meaningful conversations usually starting with “How can we . . .,” or “What about . . . ?” Then the language changes to “Does anyone has anything to say about . . . ?”

Hedgehog reflex: Whenever the big initiative is brought up, leaders ball up like a frightened hedgehog. Mentioning it is lauded extensively (thank you for bringing this up) and is immediately followed by the reflexive (but, we first have to focus on . . .).

Work under a different banner: A new supreme leader armed with new ideas and priorities is brought in, and bold initiatives from predecessors are frowned upon.

Information graveyard: The flashy website is no longer updated, newsletters cease to be distributed, and all written material is at least a year old.

Restart button: A second new initiative is launched, usually branded as building on the success of the previous one. Insiders know better. The old initiative is dead, and long live the new one.

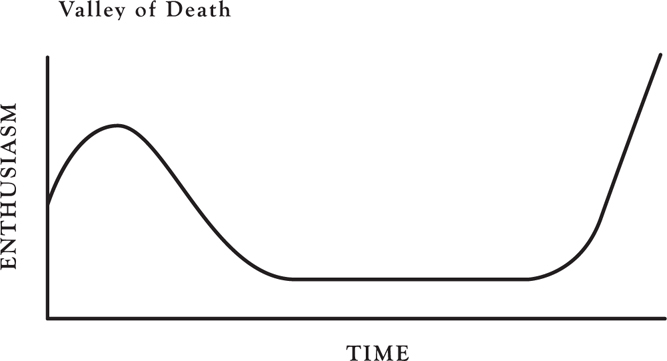

Looking at the landscape of bold initiatives that fade away like a faint candle, you recognize that governments, companies, and professionals suffer from a consistent pattern that often leads to failure. This pattern is called the Valley of Death. Figure 4.1 describes the Valley of Death: the relationship among enthusiasm, time, and goal-achieving.

Figure 4.1 The Valley of Death

The Valley of Death describes what happens with your enthusiasm between the first moment you have a vision of a new goal and the final moment where you achieve this goal in the real world. When you are first hit with a good idea, you get excited and life looks rosy. You start sharing your ideas with others and they get excited too. This is contagious and your energy level goes up even further. When you start to work on the goal, things go downhill from there. Progress is slow, others become less supportive, and at a certain point in time you reach a low-level enthusiasm plateau. This point is where many initiatives are abandoned. Only after you have persisted and crossed this plateau does your success become inevitable and your energy and enthusiasm resurge. The persistence to cross the Valley of Death is necessary for leaders who want to become experts at goal-achieving.

Why Ignoring the Valley of Death Is Dangerous

The bigger and bolder the goal, the longer and deeper the Valley of Death will be. This makes sense: The Valley of Death for developing a new software application is shorter and shallower than the Valley of Death to bring a man to Mars. Big goals require overcoming big obstacles. This is actually good news: If you don’t face big obstacles, you are probably not thinking big enough.

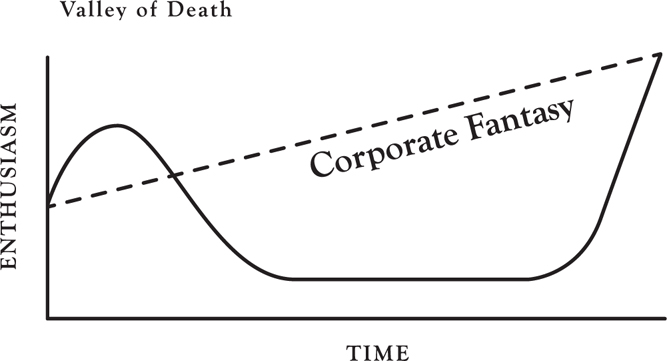

The curious thing, however, is that in many corporate environments, the Valley of Death is simply ignored and the initial planning is presented as a straight, unhindered line from A to B. Figure 4.2 illustrates this strange phenomenon.

Figure 4.2 Corporate fantasy and the Valley of Death

Unfortunately, ignoring the Valley of Death and presenting a corporate fantasy instead is often driven by the planning fallacy. The planning fallacy is a thinking bias in which we consistently underestimate the time and effort required to get a project done. There are many examples of the planning fallacy. The new Berlin airport was supposed to be ready by 2011. At the time of this writing (2018), the airport is still not ready and is facing a cost overrun of almost 400 percent. A practical way to overcome the planning fallacy is baseline thinking. Use data of similar projects as a baseline for your planning and then move up or down based on your skills and competences. Baseline thinking, of course, makes ample use of your strength as an engineer: reality-based thinking.

When crossing the Valley of Death it’s important to distinguish between a goal and an activity. A goal requires overcoming obstacles. If there are no obstacles on your way to achieving a goal, then it’s not a goal, but simply an activity: a straight line from A to B which can be done by everybody. For example, reaching your office is an activity. Reaching your office every day at 7 a.m. for the entire year is a goal. If you confuse the two and think only in activities, you will seriously diminish your potential. After all, a good goal should be stretched to the point of your slight discomfort.

Why New Initiatives Often Fail

Why is it that the plateau of the Valley of Death resembles the graveyard of good ideas, great initiatives, and boundless ambition? In my experience, the answer is procrastination. Procrastination means that you need to do something, you’re not doing it, and you feel miserable about it. Procrastination is the thief of time and it’s the main reason why it’s difficult to follow through on achieving a new goal. To overcome procrastination, you need to understand where it comes from.

For this, let’s turn to a simplified model of the human brain. This model tells us we have three different brains: a lizard brain, a mammalian brain, and a neocortex. The lizard brain is focused on one thing and one thing only: survival. It hates risk and uncertainty, and actually wants yesterday to look exactly like today and today to look exactly like tomorrow.

On the other side of the brain spectrum is the neocortex. Brain scientists sometimes compare this part of the brain to crazy uncle Joe who always shows up at family parties. He wants to do exciting things like bungee jumping, sky diving, and becoming a great business leader. In order to make this happen, he needs to embrace uncertainty and risk. This is the exact opposite of the objective of the lizard brain. This tug-of-war between the lizard brain and the neocortex is called the war between your ears.

The lizard brain is your oldest brain. Since it was there first, it has been granted veto power over your body. In other words, if it believes you will engage in risky activities, it will pull the plug and shut your body down. Hence the fact that sometimes people simply faint when they have to give an important speech. It’s an effective survival mechanism. Imagine that your neocortex one day would decide it would be a good idea to see what happens if you hold your breath for more than 15 minutes. Your lizard brain would automatically kick in after two minutes and reestablish adult supervision. The problem is that the same mechanism is activated when you try to cross the Valley of Death. The siren song of the lizard brain guides you to procrastinate and even pull the plug on very important goals.

Brain scientists have identified two blunt ways of overcoming the sabotaging effects of the lizard brain. Those would be drugs and alcohol. Needless to say, these approaches aren’t beneficial to your leadership style. Thus, to overcome the lizard brain, you need to apply subtle tools to unleash your neocortex and reign in your lizard brain.

The lizard brain is not limited to people, but has a collective cousin called organizational paralysis: the ability to linger in complacency and reject new thinking and ideas. It acts like a giant anchor, trying to bring any new initiative to a grinding halt. You may recognize the collective force built by many lizards in a company when:

- Most organizational energy goes to safe yet ineffective strategies to deal with big business problems. Typical examples are cost-cutting and multiple rounds of reorganizations when facing new, stiff competition in the marketplace.

- Senior leaders are more concerned with salary, bonuses, and other perks than with proposing and advancing bold ideas to serve customers better and grow the company. Buying a corporate jet is usually the first red flag.

- The most ambitious organizational project is something internal, such as a shiny new compensation system.

- Business breakthroughs don’t revolve around growth and customer value, but center on payment terms, request for proposals (RFPs), and other financial gimmickry.

How to Cross the Valley of Death

To become an unstoppable goal achiever and catapult yourself deep into the ranks of the best business leaders, you need practical strategies to overcome procrastination and cross the Valley of Death. The best analogy to make that happen is again to take a page from the playbook of long-term investing in the stock market.

Long-term investing success in the stock market is determined by asset allocation, diversification between assets, and minimizing costs.

Asset allocation

Asset allocation describes the amount of money held in risky assets such as stocks and safe assets such as bonds. For example, a typical investment portfolio may consist of 70/30 allocation containing 70 percent stocks and 30 percent bonds. If stocks go down, bonds may go up, and vice versa. Thus, risk is minimized. By maintaining the desired asset allocation, investors buy stocks cheaply when the stock market is down, ensuring long-term investment success.

Diversification

Diversification tells something about how diverse the components of the different assets actually are. For example, if you have one stock of one company, you’re not diversified at all, and run the risk of losing it all when this company hits a wall. On the other hand, if you own a bit of all stocks in all marketplaces, you are maximally diversified and have minimized your risk.

Costs

Cost reveals the fixed amount you lose every year for simply owning investment assets. With a long-term investment horizon of say 30 years, due to the compound effect, a cost difference of 2 percent per year on the entire investment portfolio may result in 30 percent less wealth after 30 years.

Thus, to build wealth by buying and holding investments over a long period of time with the least amount of risk, it’s important to apply an investment process. Decide and stick to an asset allocation, maximize the diversification within the assets and minimize costs. The same philosophy can be applied to achieving big goals as well. In Chapter 3, we have seen how you can use the allocation of your strengths—reality-based thinking, process design, and accelerated learning—to drive business growth. By focusing on marketing, sales, and strategy, you can apply the power laws and minimize energy and costs to achieve big goals. Now, let’s take a look at how diversifications and option development will help you as a leader.

Why Options Are Essential to Achieving Goals

To lull your lizard brain, it’s important to reduce risk. The riskiest plans have only one route to solution. If this approach fails, the entire plan fails. Therefore, it’s important to have multiple alternatives in order to achieve your goals. These alternatives are called options. They reduce risk and increase your chance of achieving your big goal. Figure 4.3 illustrates the role of options in achieving your goal.

Figure 4.3 Impact of options on goal-achieving

If you want to go from A to B and have only one option to get there (the path with the multiplication sign), you get stuck if you face an obstacle. On the other hand, if there are alternative routes (the paths with the circles, pyramids, and triangles), you will be able to switch to a different option as soon as you face an insurmountable obstacle. Developing options therefore gives you freedom. If you don’t have options, don’t bother. It’s better to use your energy elsewhere. With only one option, you have a problem. With two options, you have a dilemma. Freedom, choice, and reduction of risk arrives only when you start to cross the Valley of Death with three options or more. You diversify your plan, and the chances for success increase exponentially.

Developing options is a numbers game. It is also one of the most difficult things to do. To understand why, ask yourself a question: What is the purpose of thinking? A philosopher may have multiple answers: To live, solve problems, survive, etc. Yet a brain scientist will have only one answer: The purpose of thinking is to stop thinking. This means that thinking is a high-energy-consuming activity. People are hardwired to think in the shortest time possible so they can return to autopilot: unconscious thinking. For example, driving on autopilot is when you drive a car for 20 minutes and afterward simply can’t remember anything about the drive. Scientists estimate that more than 95 percent of your life is run on autopilot. Thus, when faced with a problem you tend to think until you have something that resembles a solution. The urgency is to immediately stop thinking and turn to execution instead. This is why option development is so hard.

Practical Application

Here is a systematic process for creative option development. It can be either used individually, or applied as a powerful brainstorm technique with a team:

- Take a new sheet of paper and define your goal as a question: How can I . . . ?

- Write down and number all the possible solutions to this question.

- If the problem is significant, the first 5 to 10 solutions you write down will be fairly easy. They are generated spontaneously by the conscious mind.

- Solutions 10 to 15 will be difficult because they require hard thinking and force you to create new associations. Your initial instinct is to stop thinking and give up. Don’t give in to this instinct and continue.

- Solutions 15 to 20 are difficult. However, force yourself to continue until you have written 20 solutions on paper. Oftentimes the breakthrough insights and creative ideas will be found in the last five solutions.

- Pick your best solution. Perform another option-development exercise based on this solution: How can I . . . You will be baffled by the brilliance of your own mind.

A scientific training in hard engineering sciences sometimes assumes a single answer to a problem. After all, the world is upside down if 1 plus 1 no longer equals 2. Yet, engineers are also trained to consider multiple options to deal with typical engineering problems. For example, various carmakers apply different technologies to reduce fuel consumption. Therefore, business leaders need to make a clear distinction between digital problems (there is only one answer) and fuzzy problems (there can be multiple answers). Because a business goal is almost always fuzzy and involves all kinds of decision criteria, multiple routes to a solution are possible.

Option development typically happens at two moments in time. The first moment is before you commit to achieving a big goal and start your journey to cross the Valley of Death. This moment is called exploring options. The second moment occurs when crossing the Valley of Death, called portfolio thinking.

How to Explore Options before Entering the Valley of Death

If you only focus on one route to a solution and put all your eggs in a single basket, you will invite trouble. You burn bridges and shun a plan B. The thinking is that safeguards such as a plan B invite cautious behavior, thus preventing a leader from taking bold steps. The flaw in this approach is that the most successful leaders take bold steps, while at the same time mitigating the downside of risks. If you jump from a plane with a parachute, you have made a bold choice. Adding a spare parachute significantly reduces risk, thus making the jump exciting and relatively safe. If you refrain from adding a spare parachute, you will neither increase the chance of making bold decisions—jumping out of the plane—nor show more persistence when things go pear-shaped. The reason is very simple: You tend to overestimate skill and underestimate luck. A more prudent decision is therefore to create an environment where skills thrive and luck is reduced. You should therefore explore alternatives before entering the Valley of Death.

A strategic plan without options to get there is dangerous. To keep a plane in the air, it is wise to have independent backup systems when things go wrong. This is not always obvious, because many leaders confuse strategic boldness with decision-making boldness. Strategic boldness is a do-or-die strategy. Initially praised by pundits, the bold leader is quickly abandoned when things don’t work out well. Think of the carmaker Fisker, which started out with wide approval, yet had to abandon its vision of making electric cars when losses started mounting. Tesla walked the same road and, so far, has made it. This doesn’t mean that the Tesla approach to taking risks is a successful one. After all, you may be dealing with survivor bias, devouring the one big story of monumental success, while simply forgetting the many others who didn’t make it in our success universe. This is the pitfall of strategic boldness.

Decision boldness, or triage, on the other hand, forces an organization to develop options before committing to cross the Valley of Death. As a leader it’s important to adopt the mindset of triage when it comes to decision making. Triage is the decision model adopted in field hospitals in war zones. It ensures the survival of the maximum amount of wounded people with a limited medical supply. Triage is a useful model for business leaders, since resources are limited by definition. The idea of triage in business is to never settle for activities with a low-reward or a high-risk profile. After all, it’s best to use organizational energy elsewhere. I’ve seen companies fall in love with extending payment terms to their vendors to save a few dollars, while at the same time losing the plot when it comes to innovation power. This practice is called myopic optimization. If the Titanic has been ripped open by an iceberg, don’t bother with repairing a leaking sink in the passenger cabin to stop the flooding.

If you find yourself heavy with activities which are both high risk and high reward, it’s time to be bold and either develop alternatives with a lesser risk profile or focus on mitigating risk. For example, if you implement a new IT system to logistically serve your customer better, a mitigating strategy is to run both the old and new system in parallel until the new system having proved itself.

Therefore, before you commit to crossing the Valley of Death, ensure that you not only have options to help you achieve success, but also make sure that each option provides a high reward and carries a low risk.

How to Apply Alternatives while Crossing the Valley of Death

If you ask project managers if it’s important for their project to be successful, the answer will of course be affirmative. Otherwise, their work is fairly useless and their time can better be used elsewhere. Project managers will therefore do everything in their power to turn an important project into a big success. If you pose the same question to the CEO, the answer would be very different. The CEO looks at all projects and is generally interested only in the aggregate result of the entire basket of initiatives. This is called portfolio thinking. In other words, the result of the individual pieces is irrelevant; what counts is the overall result.

For an investor, only the overall result of the entire portfolio matters. In investing, generally speaking, things don’t always feel that way. Many investors become itchy when they look at underperforming parts of their portfolios and start making unwise decisions, such as panic selling at the bottom of the market. The same behavior may be true for a CEO: why not cut the cord on the initiatives that are lagging? This decision isn’t straightforward though. Are the initiatives lagging because the chances of future performance are very limited, or are the fluctuations in performance due to external circumstances that will likely change? In this case, getting rid of lagging assets would increase risk and decrease performance.

Once they have committed to their goal, leaders therefore need to make a judgment call to apply portfolio thinking correctly while crossing the Valley of Death. The following parameters will help you to make the right decision about which initiatives to continue and which initiatives to kill on your way to achieving your big growth goal.

Predefined Intermediate Milestones

It’s never a good idea to start without a good plan. A good plan always contains conditions that need to be met in order to continue to the next phase. For example, when developing a new project, an intermediate predefined milestone could be the first customer sale at a certain moment. If the sale happens, do continue. If the sale fails, quit the project.

Common-Cause Success or Failure

If the success or failure of two different initiatives depend on the same circumstances, you’re dealing with a common-cause success or failure. For example, a common-cause failure on safety equipment can be the interruption of power. If both the safety interlocks and the emergency shutdown system depend on the same power supply, you can’t rely on the safety performance of the two systems independently. If the power supply fails, they both fail. The same can be true for new initiatives. If the success rate of launching two different products has a common cause, such as the fortune of the same customer for both products, these two products may win or fail at the same time. If you kill one, you may want to kill the other too.

Time Horizon

If you make decisions too quickly, you may destroy a great initiative before it’s hatched. If you make them too slowly, you may drag underperformers as anchors on your results. The optimum time horizon depends on your circumstances. In a marketplace with fast and direct feedback, portfolio decisions may happen more often and quickly. This is the principle of failing fast. If time horizons are long, such as with reservoir engineering, where oil field development may take a decade or more, it’s best to design a broad portfolio with as many eggs as possible, and hang on to this portfolio for a much longer time. Here, you can apply the strengths of accelerated learning.

Why Few Decisions Matter in Overcoming Obstacles

Another interesting phenomenon in stock investing is that over a long period of time, the vast majority of stock market gains occur only on a few days. If you miss these days because you’re not invested in the market, you run the risk of missing almost all of the market gains. This is the effect of the vital few.

As a business leader, it’s not only important to become aware of the vital few phenomenon, but it’s really helpful to make active use of it. In the end, for business success, only few decisions really matter. Some decisions really count if you want to cross the Valley of Death.

First, do you fall in love with your company, project, and product, or fall in love with your client? One day, I designed a complete, intensive two-day leadership workshop to help a company grow in the next few years. The day before the workshop, a huge reorganization literally changed the complete landscape. If I had fallen in love with my product, not much would have changed in the execution of the workshop—valuable for the customer, for sure, but less applicable because of the changing circumstance. I realized I had to fall in love with the client to help the company further. Overnight, I completely redesigned the workshop. Now it was aimed at giving participants all tools needed to deal with these changes. The outcome was a great success.

Second, do you push your organization to dismiss the mediocre and the obvious, and focus on the bold and breakthrough instead? You will need only a few breakthrough ideas to create an enormous amount of success. On the other hand, you need a lot of small and mediocre ideas to match this achievement. Often, the organizational time and energy spent on executing a few small ideas is not much different from the organizational time and energy spent on a big idea. The question is how do you direct the limited resources of an organization to bold and breakthrough thinking? As you’ve seen in the previous chapter, a focus on marketing, innovation, and strategy is always a very good use of resources.

Finally, where do you spend your own time as a business leader? Do you anticipate the Valley of Death, push your people to prepare options, explore alternatives, and apply portfolio thinking? Or do you set the vision and hope the organization will get the work done? Your active involvement in driving portfolio thinking and triage is one of the most important leadership activities you can engage in.

Summary and What’s Next

This chapter has described a process for crossing the Valley of Death. This process builds on your strengths as engineers. Reality-based thinking ensures that you expect and prepare for big obstacles on your way to achieving your goals. Applying triage before crossing the Valley of Death ensures that you select the options with the highest up side and the lowest down side. While crossing the Valley of Death, you can use accelerated learning to actively look for feedback on your progress and apply portfolio thinking to maximize your chances of success.

Now that you have seen several strategies that build on engineering strengths to cross the Valley of Death, the following chapter will focus on the next piece of the goal-achieving puzzle: How does your behavior as a leader influence your ability to achieve big growth goals?

External Perspective

Interview of Marcel Berkhout, CFO, MeDirect Bank

What Has Been the Most Fascinating Aspect of Business Leadership for You?

We are a young bank in a dynamic environment. Our bank is showing business leadership through our innovative client approach. It’s amazing how much we can achieve with our dedicated team of great professionals, by simply putting all our energy and focus on those parts of the financial industry where we are at our best.

Our leadership can also be evidenced in our new ways of working. As CFO of the bank, I’m heading our financial reporting and balance sheet management. I work out of Brussels. Yet, a large part of my team is located in Malta and London. We work together intensively with, for example, lots of conference calls and other forms of interaction. Our modus operandi is fascinating but can be quite demanding.

What Are Some of the Most Important Skills and Behaviors for Business Leaders with an Engineering Background to Improve their Effectiveness?

As engineers, we are trained to be precise with numbers. Yet, when taking a decision, a good feeling for the order of magnitude of a number and understanding second-order effects of the decision are equally important.

Let me make this more concrete through two examples. The engineer at a refinery who considers changing the temperature in a distillation column, needs to understand the materiality of the change and the effects further downstream in the process. Similarly, at a bank, when we decide about our treasury bond portfolio, it is not only a matter of assessing risk and return, but also assessing the effect on the bank’s solvency and liquidity ratios. Having an engineering background helps.

Engineers need to be careful to embrace the idea that developing leadership skills can only be achieved through formal “management” skills trainings. In my view, it’s important to remain authentic, otherwise you lose credibility. The fastest way to grow as a leader is by leading, adjusting your behavior based on feedback from the people around you, and always enjoying what you are doing.

What Is Your Approach to Learning and Improving as a Business Leader Yourself?

With experience, you also gain perspective. It’s a sign of maturity to admit mistakes. This has enabled me to improve my own judgment. Also, the biggest setbacks have been the biggest learning opportunities for me.

What I have found is that often informal conversations with leaders and professionals from different fields provide great new ideas. I want to reserve more time for this kind of opportunity to learn and grow.