A Survey of Change and Change Models

Change Management and Common Sense: Things Change Managers Would Likely Do without Models

Physics informs us that “an object at rest tends to remain at rest; whereas an object in motion tends to remain in motion.” Although the domain of organizational change management has little to do with physics, this principle does appear to readily apply. There is familiarity and comfort with adopting a routine and doing the same things in the same way over a long period of time. Changes made to the way things have always been done is uncomfortable for most employees. Discomfort leads to concern as well as uncertainty. Uncertainty about the future will always exist even when the news announcing change is apparently positive. Uncertainty then tends to fester over time and multiply as employees voice their concerns to one another in the hallways of the company and by the watercooler. Uncertainty reaches the point where it leads to fear—fear of the future and the unexpected. Fearful employees then seek to return to the comfort that they once knew, and in doing so, tend to resist the changes suggested by senior management. Change therefore tends to trigger a cycle of “routine, comfort, uncertainty, fear, and resistance.” Managers attempting to change the organization to a new operation with improved performance and improved alignment with strategy are often at a loss at deciding how to succeed at creating such change. Change will always involve breaking with routine and introducing some level of uncertainty. Change managers will therefore encounter uncertainty, fear, and resistance regardless of the nature of the proposed change. They must expect it, prepare for it, and address it in change management initiatives.

A start at creating change in the face of resistance might involve thinking about how to intervene in the negative spiral associated with the disruption of employees’ comfortable routine. Common sense would suggest that as a fundamental first step, managers should attempt to clearly communicate the rationale behind the change that may be perceived by employees to be a disruption of a previous routine. Change management understand that there is a link between the discomfort of parting with the routine of today and the uncertainty associated with the new ways of doing things. It is paramount for managers to consider how to reduce uncertainty by painting a picture of what the future will look like, and how and why this is preferred over the routine of the past. Common sense would further dictate that managers would involve employees in some way in designing the change as well as in the implementation. Asking employees to go along with plans developed by someone else is far more difficult than assigning employees to contribute to the design and development of a plan that they would now consider to “own” even in some small way. To make an analogy, an airline pilot flying through a thunderstorm would be likely feel a greater sense of security than the typical passenger in the rear of the plane who is being jostled by the uncertainty of constant turbulence. The difference between the pilot and the passenger with respect to uncertainty and fear is the sense of control over one’s own destiny. Stakeholders in change management initiatives who feel that they control their own destiny feel more like pilots than mere passengers.

In the same way that successful airline flights eventually find a way through the turbulence and land, change initiatives get carried out despite the headwinds and turbulence. Such changes are incorporated within the organization and feature revamped processes (Figure 1.1). It is at this point in the change process where the reality may not quite match the beautiful picture painted by managers. There will likely be growing pains that feature the desire to return to how things were done in the past. Once again, managers communicate on an ongoing basis the rationale behind the change, the promise that things will settle once again into routine, and that when they do, the future will be brighter than the past.

Figure 1.1 Change from the perspective of a pilot and passenger

How then does common sense inform executives and senior managers in the design and implementation of change initiatives? To summarize, it is all about effectively communicating the rationale behind the change, providing a clear description of an image of a better future, reducing uncertainty and fear by instilling employee ownership in the design and implementation of change, and finally continually reinforcing the change to ensure that employee buy-in continues. Common sense suggests that when many people will be affected by change, they should be informed and their input should be solicited. Understanding the relationship between change, uncertainty and resistance, fear, and day-to-day human behavior therefore leads to common-sense measures that work to reduce that almost automatic “push-back” from employees that is motivated by fear.

Change Management Models: What

Are They and Why Use Them?

Though common sense provides guidance to managers who have it, formal academic models exist that seek to provide guidance and direction to managers who are more comfortable with following a prescribed series of steps to alter the current course of their organizations. Further, many managers do not have the time to think through a custom methodology for implementing change. Change managers need all the help and advice they can get, and they therefore reach out to thought leaders in the field for guidance. Academic models are attempts to not only explain what has happened when successful change was carried out, but what should happen as well. Some change management models tend to be descriptive. These models do little more than attempt to describe what happens during change. Other models are prescriptive. They inform managers what, in the view of the creator of the model, what “should” be done when initiating and implementing change. Often these models are based on hard experience from both success and failed change over a period of many years. Change management frameworks are also based on collected data from change managers to inform the researcher on what was done, how it was done along with results that inform what should be done as a matter of good practice. It pays to remember that these ideas are models of reality rather than reality itself. Change management models can work, but this is no guarantee that they always do work. The same could be said for most business practices. It depends on the context, how the practice is implemented, who implements it, and how well it is managed.

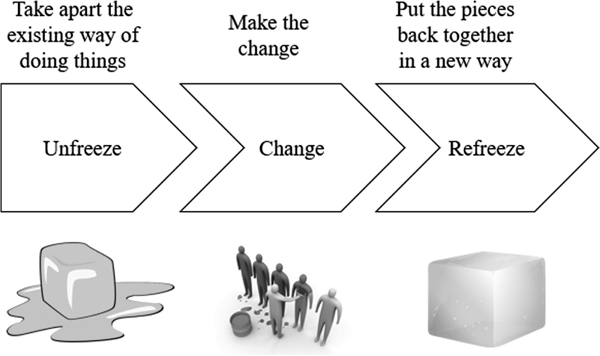

The Lewin Model: Unfreeze, Change, Refreeze

Lewin is a seminal author in the field of change management. Lewin informs us that change involves three steps—one of which—rather redundantly—is “change.” The first step in the three-step process uses a term “unfreeze.” To unfreeze an organization is to prepare it for change by breaking apart the legacy patterns of doing things. This is in effect taking “an object at rest” and giving it a push so that it is moving again. This is easier said than done given the natural uncertainty associated with change and the resulting resistance. However, common sense informs managers that a change effort cannot be completed unless it is first started, and unfreezing is starting the process. The real question is “how”? Unfreezing implies stopping something and taking a different action, for example, taking ice cubes out of the refrigerator and letting them melt.

For naturally talented leaders, the way to start is to put stakeholders at ease by sharing a vision for the future and including them in the change plan. In fact, such activity, reminiscent of unfreezing or melting ice cubes, is often referred to as “warming up.” Ideally, unfreezing should result in receptive stakeholders who understand the intended change and the underlying rationale.

The next step in Lewin’s framework is “change,” but this is a single word that speaks volumes. The “change” phase focuses on implementing new processes, new practices, and new systems. There are many ways to do this, including training, practice, role-playing, and scenario planning, to name but a few. In most cases, things get worse before they get better as stakeholders gradually work through the discomfort of doing something in a new way. Eventually, if the change is successful, performance improves. Lewin then informs the manager that the change must “refreeze” into the organization. This term is shorthand for “institutionalizing the new way of doing things” (Figure 1.2). Once the company is familiar with the new way of doing things to the point that it is no longer new, and the application of new processes and systems comes naturally, it could be said that refreeze and institutionalization of the change has occurred.

Figure 1.2 Lewin’s model of managing change

Source: Lewin (1947).

The Lewin framework expresses what is observed in common-sense thinking about managing change. Change must begin, it must be carried out, and the change must become a way of life. While the Lewin framework provides a structured path to follow when initiating and managing change, the phases are expressed in a compact form and require elaboration by any given manager. Presumably, effective managers could successfully employ Lewin, whereas others, following the same three phases, could easily fail and often do. It appears from inspection of the process that the Lewin framework could emerge from a common-sense consideration of what ought to happen within a change management scenario. Further, the three steps in the Lewin framework could be viewed as phases or categories of activities. Change managers could take this and develop a project around it. This could be done by identifying the desired deliverables from “unfreeze,” “change,” and “refreeze” followed by populating a schedule with activities and resources.

Kotter’s Eight-Step Change Model

The Kotter’s change model provides detail and structure far beyond the three-phase Lewin model. The eight steps are as follows:

- Create urgency

- Create a coalition

- Develop a vision and strategy

- Communicate the vision

- Empower action

- Get quick wins

- Leverage wins to drive change

- Embed in culture

An examination of the Kotter model suggests similarity with both a common-sense approach and the Lewin model, albeit with additional detail. Steps 1 to 4 appear to relate to preparing for change, “unfreezing,” and reducing the uncertainty in the organization. Steps 5 to 7 involve carrying out the change by aiding the organization in getting things done while attempting to create a positive spiral of success. The implementation of change begins with things that can be accomplished quickly so that successes can raise the energy level and work to minimize the resistance to change. The thinking here is that resistance to change can be expected to decrease if positive results are observed by the stakeholders involved in change. Finally, new systems and processes are institutionalized by embedding the change in the culture, or in Lewin’s terminology, “refreezing.” “Embedding in culture” need not be a top-down effort from outside of the organized. Instead, it could be something that emerges from the practice of new processes, policies, and practices over time. In fact, this is known to occur in companies that exhibit an emergent strategy and culture rather than one dictated from the leadership level of the firm (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 Kotter’s eight-step model

Source: Kotter (2012).

Observations on Kotter

The Kotter model provides some interesting guidance to the manager. The first key point is that of urgency. It is observed that change leads to uncertainty and resistance that must be overcome by the change manager. Kotter makes the point that managers must not only answer the question of “Why change?” but also “Why change now?” The second key point that Kotter makes that extends the Lewin framework and the common-sense approach is to seek small victories or “quick wins” in order to provide evidence for the benefits of the proposed change as well as to build some positive momentum. The Kotter model is said to

“extend” the Lewin model because although Kotter follow the general pattern of the fundamental stages of the Lewin framework, the Kotter model provides additional detail and guidance that in Lewin remains implicit.

PROSCI “ADKAR” and Three-Phase Model

PROSCI, an acronym for “professional science” is a consulting company dedicated to the art of change management. Two notable frameworks are promoted by PROSCI: the ADKAR and the three-phase change model. ADKAR is an acronym that stands for Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, and Reinforcement. The Awareness and Desire elements of ADKAR play a role in uncertainty reduction by reinforcing the need for change as well as describing the nature of the proposed change. The term “Desire” is aimed at engaging stakeholders in such a way that they support the change and want it to occur. Assuming that “Desire” is accomplished in the ADKAR framework, resistance to change will be likely to fade. On the other hand, desire and good intentions do not necessarily lead to results unless the appropriate know-how exist. This is where the “Knowledge” element comes into sharp focus. Once appropriate skills and behaviors are in place, the new knowledge combined with Awareness and Desire lead to Ability or the actual implementation of change. Finally, once the organization has changed, the new systems, processes, skills, and behaviors are Reinforced so that they become “frozen,” “embedded” or institutionalized.

The ADKAR model reads much like a content model for change management as it lists all elements that should be included in a change management plan rather than describing the process steps to be carried out. PROSCI, however, also offers a three-phase process model that emphasizes the sequence of events in managed change. The PROSCI three-phase model is given as follows:

- Preparing for change

- Define your change management strategy

- Prepare your change management teams

- Develop your sponsorship model

- Managing change

- Develop change management plans

- Take action and implement plans

- Reinforcing change

- Collect and analyze feedback

- Diagnose gaps and manage resistance

- Implement corrective actions and celebrate successes (Figure 1.4)

Figure 1.4 PROSCI and ADKAR

Source: Prosci (2019).

It is of interest to observe that the PROSCI three phases appear to mirror the Lewin model. Unlike Lewin, however, the three-phase model does not express the ideal of “refreezing” or “embedding” change, but rather appears to view change as something that requires ongoing management attention. Further, the initial phase emphasizes strategy, sponsorship, and teams. This suggests that initiating change must be supported with a clear plan of action, executive support in the form of sponsorship, and finally with teams of employees affected by the change.

Observations on PROSCI

PROSCI models have much in common with Lewin and Kotter. The three-phase model closely mirrors Lewin, with possible differences in how institutionalization of change is viewed. The ADKAR model is in apparent alignment with what common sense and other models would suggest. The initial elements of the model involve components tailored to the need for the reduction of uncertainty and resistance prior to implementation and institutionalizing of change. The ADKAR model stands out in its emphasis on the requirement for new knowledge and skills to support change. The desire to change without the requisite know-how increases the chances of failure. Further, the in-depth guidelines provided by

PROSCI ring true as the result of significant experience and research.

McKinsey 7-S Model

Unlike other models, the 7-S presents an image of the key elements of the organization as well as how they are linked together. The 7-Ss are given as follows:

- Shared values

- Strategy

- Structure

- Systems

- Style

- Staff

- Skills

Each of the Ss are connected directly or indirectly to other elements. This image suggests that a successful organization requires all elements to function well and to function well together. The 7-S framework is not so much a change management model per-se, but rather a guide for what to think about when embarking on change. The idea being expressed it that as each “S” connects to all other Ss, no “S” may be overlooked when embarking on change. The 7S model therefore appears to be a content rather than a process model for change. Unlike the phased approach of Lewin, the 7-S says little about where to start and finish, but rather what to include and what to think about when embarking upon a change management initiative (Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5 McKinsey 7-S model

Source: Jurevicius (2013).

Observations on 7-S

A concern of any model is that it is an attempt to represent reality with an idea or picture of the underlying reality. All models imperfectly characterize reality, but some models are better than others. Is the 7-S model “better”? The answer is “it depends.” The right model used in change management could fail as a result of the wrong implementation. Also, thinking managers should carefully consider each proposed model in a critical manner. For example, McKinsey characterizes the firm in terms of “7-S,” but then again, why does it have to be “7-Ss”? Why not 6 or 8? Or, 7-Ss and one A, N, or B? The 7-S content model of the firm may be considered a useful framework when applied in change management initiatives, but the result will depend on a well-thought-out execution. One example of this is the consideration of the linkages between each “S” in the model. What specifically are the links intended to convey? Are the linkages a general-purpose perspective on the components of all companies and how such components are linked? Do the links apply to your specific company? Should they? Finally, is each link intended to express one-way, two-way, or multi-way relationships? Managers would be well-advised to arrive at a clarity of understanding of the relationship of all elements of this model prior to attempting to implement it.

Senge and Systems Thinking

The “system thinking” of Senge appears to be related to the 7-S model in that Senge views the firm as an interconnected web. Unlike the 7-S model, Senge does not specify a list of connected functions, but rather emphasizes the connections between the functions. The firm is therefore viewed as a complex system with a significant number of feedback loops. Organizations tend to go off the track when leadership neglects or fails to understand the linkages and resulting feedback loops that exist. This is a cited reason for why new policies championed by leadership often fail. Further, Senge’s view suggests that the documented organization chart does not accurately capture how individuals interact within an organization. A map of frequent connections between individuals and corresponding feedback loops would likely appear to be very different from the organization that is captured in the static organization chart. The organization should therefore be viewed as a complex system (Figure 1.6). It follows then that any changes to a complex system must be carefully considered and only undertaken when the system is fully understood. An analogy of the “organization” as system view could be provided in an automotive mechanic suggesting an action designed to improve engine performance. Engines have become more complex over time and as a result are controlled by microprocessors. Mechanics proposing change suggestions therefore require significant training, a holistic understanding of how the engine works, and certification. The Senge’s view of the organization would appear to suggest that not everyone is qualified to suggest and implement organizational change. Perhaps it takes the organizational equivalent of a “certified mechanic.”

Figure 1.6 Senge and systems thinking

Source: Senge (1997).

Observations on Senge

While Senge does neither provide a process nor a content model for change, Senge does introduce a way of thinking essential to managers of change. Senge’s view of organizations as systems reinforces the underlying cause for the “law of unintended consequences.” That is, change initiatives embarked upon without an adequate level of understanding of the underly systems involved is bound to have unexpected results. Since change initiatives are known to fail with often spectacular unintended consequences, Senge’s “system thinking” is a thoughtful approach for which change managers should seriously consider. The conceptual nature of the Senge systems’ view of organizations is reminiscent of the theory of constraints philosophy introduced by Eli Goldratt in the seminal work “The Goal” first introduced in the late 1980s. Goldratt explains in this work that an operation can go no faster than the slowest element within the system. If a change manager wished, for example, to improve the output of a factory, the manager would identify the bottleneck or constraint, widen the bottleneck to improve overall throughput, and then finally identify and widen the next bottleneck using an iterative approach. A manager who took steps to increase output in an area of the factory in front of a bottleneck does little more than create unnecessary inventory. Like Senge, Goldratt proposes a means for developing insights regarding how the “pieces of the puzzle” fit together. Change managers who employ such conceptual models will have a better chance of identifying and solving the right problem.

Which Model Should Be Selected?

It is observed that change management models are many, yet successful change initiatives are few. From examination of well-known change models, it is observed that some describe a series of steps to be undertaken, whereas others suggest what change managers should consider when embarking upon change. Given that any change model may or may not succeed depending on the implementation of the change, managers could benefit from examining several different models such as have been presented in this text. A well-informed change manager might—rather than employ a single model—glean from the inspection of change models a few important guidelines to think about when initiating or managing change. Such guidelines might include the following:

- Employ a systematic approach

- Understand that a natural resistance to change exists in all organizations

- Involve those who are affected by or have a stake in the change

- Understand how the pieces fit together as well as how they interact

- Make sure that you correctly understand the nature of the problem that your change initiative seeks to solve