HOW TO GET THE BEST OUT OF THE PEOPLE YOU WORK WITH

Bill Green, the US art director and author of the popular ad blog Make the Logo Bigger, claims that when he was a student, a senior creative told him: “Be nice until you get in, then you can be an asshole.”

Amusing as that quote is, I’d say there’s never a reason to be rude to anybody, and plenty of reasons to be civil.

Some creatives find this hard—perhaps because our job is primarily about ideas, not people; we are constantly hunting something down in our minds, and being civil takes effort, and means you have to snap out of your train of thought.

But it’s worth it.

First of all, it won’t help your career if you get a reputation for being rude. And it will help if you have a reputation for being friendly and likeable. So even if you’re not naturally warm and cuddly, it really is worthwhile to at least be polite and good-tempered.

Quite simply, you’ll find people are more likely to help you if you’re nice to them.

Always bearing in mind…you don’t want to be so gentle that you fade into the background.

This may be more of an issue in some countries than others. Simon Welsh, executive creative director at BBDO Guerrero in the Philippines, points out that it’s part of most Asian cultures to respect one’s elders, much more so than in the West;

“As a result, many young creatives are too shy and respectful to give their point of view. Those with the self-confidence to stand up for their ideas (as long as they do so without calling their boss an ignorant tosser) can go far.”

HOW TO WORK WELL WITH PAS

When I was starting out, every creative department had several PAs who typed the creatives’ scripts and kept track of their whereabouts.

Nowadays, all creatives can type and have mobiles, so the role of departmental PA has disappeared. But the executive PA, who “looks after” a creative director, remains.

It may be argued that a personal assistant is more of a luxury than an essential. For sure, part of the job involves booking restaurants, fetching coffee, and buying flowers for the CD’s wife and mistress. And yet… even these trivial duties may be invaluable. A creative director’s time is costly; it makes sense for an agency to get the most out of it. For example, it probably works out ten or 20 times cheaper for the agency to send a PA to buy his sandwich than for the CD to go out and buy his own.

But the executive PA plays another, truly crucial role—managing the “Tetris” that is the CD’s diary. Most creative directors have far more people wanting to see them than there is time available, which means their diaries are completely overloaded. “I quickly saw that even ‘bottom scratching: 5 mins’ needed to be scheduled”: the words of one ex-PA.

Diary-handling means that the PA wields a great deal of power—as the CD’s gatekeeper. Since everyone who wants to see the CD says it’s urgent, it’s up to the PA to decide which cases really are urgent, which can wait, and which just don’t need to happen at all.

So make sure you get on with her. If a CD’s PA likes you, she’s more likely to find time in his diary for you, more quickly. More time with the CD means better feedback, less time wasted, and more opportunities for you.

A minority of PAs, it’s true, are rude. Some of them think that just because they are near to the top person, they have the right to behave as if they are at the top too. A copywriter with 12 years’ experience in the industry can understandably get annoyed when a 22-year-old, who knows nothing whatsoever about advertising, treats him like dirt.

They believe they can get away with acting like gods because whatever they do, you’ll still have to be nice to them. And they’re correct. Unfortunately, however arrogant or difficult a PA may be, you cannot be snappy, as this will get reported back to the boss, and it is you who will end up with the reputation of being arrogant or difficult.

You have to get on with this person. And it isn’t actually that hard. In some agencies, the PA may be a wannabe creative, so you will naturally have lots in common, and you may even be able to help each other out. In other agencies, the PA may be a “professional PA,” who may be of a different gender to you, a different educational background, and have different goals. Well, so what. You get on with this person the same way you get on with anyone else in life—find out what you do have in common, and talk about that.

(As an added incentive, bear in mind that PAs are often at the center of the agency’s social life, have all the best gossip, and always have the CD’s credit card when it needs to be placed behind a bar.)

HOW TO GET THE BEST OUT OF TRAFFIC

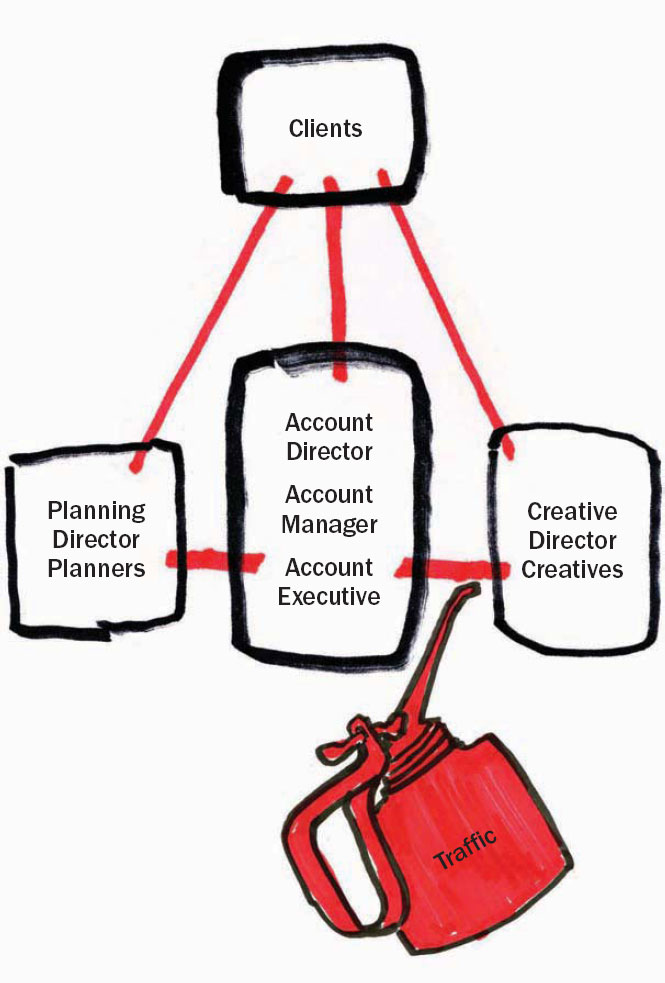

Traffic (also known as progress or project management—the department goes by different names in different agencies) does a job similar to that of air traffic control at an airport; managing the flow of work through the agency, and bringing each project safely home.

When a client decides they need to advertise, the planner and account team will write a brief for what the advertising should say and what it’s expected to achieve.

They will also let the traffic department know, and while the brief is still being prepared, the traffic department, along with the account team and creative director, discuss how to resource it—whether it’s a relatively simple brief that can go to a single junior team, or whether it’s a big opportunity (or a big problem) that they want a more senior team to tackle, or several teams, and whether there are any creatives whose skills or interests make them particularly suitable for this brief.

For example, if one of the agency’s clients is sponsoring the FIFA World Cup, that brief is best placed with a team who like soccer. If the client is sponsoring the National Ballet, that brief may go to a different team.

Once the brief has been assigned, the traffic person organizes all the meetings that need to happen—the briefing session for the planner to brief the creatives, any research trips or brainstorms that may be taking place, creative reviews in which the creatives will present their work to the creative director, and the meeting to present the work to the client.

The traffic person monitors the process closely—ready to move meetings back if it looks like the project will need more time, or add more teams if the assigned ones don’t crack the brief.

Once the client has approved the work, the traffic person supervises its production. Most agencies have specialist TV producers who look after TV and radio production, and perhaps digital producers who look after online work. But it’s normally the traffic person who supervises print work, which may include sourcing and negotiating with photographers, or buying stock shots (though some agencies have a separate department called art buying, which takes care of that).

Then once the job is completed, the traffic person puts a big line through it on their worksheet. They love organizing—their idea of an hour well spent is an hour sorting out their to-do list.

Bear in mind that some traffic people are professional project managers and aren’t necessarily interested in advertising. As far as they’re concerned, they could be shepherding boxes of machine tools through the system. That’s fine. Their efficiency and problem-solving skills can add a lot to the process, even if they wouldn’t know the difference between Frank Budgen and Franklin Gothic. Others do have a strong interest in advertising, or design. They may have a wealth of information they can pass on about the sort of work the client normally buys, or which photographers to use for your project.

In general, traffic are rarely the best-paid, highest-educated, or most ad-literate people in the building, but they do play a crucial role. Like the oil that lubricates an engine, you may not think they’re as significant as the more glamorous parts like the pistons or the spark plugs, but you would certainly notice if they disappeared. The whole system would grind to a halt.

In my first year in advertising, I once asked a senior creative—“Who’s it better to be really in with—the account handlers or the planners?”

His reply was “Traffic.”

Of course you should make friends with everybody. But there are good reasons to make a special effort with traffic.

REASONS TO MAKE A SPECIAL EFFORT WITH TRAFFIC

First of all, they know when the good briefs are coming up. And if they like you, they might even give you one. Nowadays, many agencies put all briefs that are currently “in the system” up on their intranet, so there’s greater transparency than there used to be, and perhaps less need to sneak around, or buy drinks for a traffic person, to find out what’s going on. But it’s still worth consulting traffic if you’re interested in a brief, because they’ll have more knowledge than you could glean from the mere listing—like whether it’s a real opportunity or not.

Traffic may also know which juicy brief a senior team are struggling on; get ready to jump in.

If you like gossip (and let’s face it, you do) the traffic department—because they get around the building so much—can tell you who is about to be fired, who is sleeping with whom, and other such tidbits.

They can also, if you ask them nicely, give you more of the most precious commodity of all. Time. Always communicate openly and honestly with your traffic person. If you are struggling with a brief, there’s a natural tendency to lie, and pretend that everything’s fine, because it’s embarrassing to admit to being in difficulties. However, you’ll be much better off telling the truth. Sure, you should embellish a little—explain how you’ve been sooooooo busy on other projects, and how you lost a couple of days when the planner had to go away to clarify that one crucial detail...no one wants to look bad, after all. But if you admit when you’re in trouble, and the traffic person has sympathy for you, they may be able to buy you a little more time, by putting back a deadline somewhere else in the process.

The head of traffic is especially important, because that person is heavily involved in brief allocation. If you can give the head of traffic the impression that you are a bright, lively, friendly, and hard-working team, then so much the better—they will put you up for good briefs.

Upset them, and you’ll find yourself doing briefs for tray-mats, where your work will be a surface onto which people squirt the little sachets of ketchup in McDonald’s. So, make friends with traffic. It will do you good to talk to someone who isn’t called Tarquin or Julian for a change.

HOW TO GET THE BEST OUT OF DIRECTORS

There’s a lot of mystique around directors.

Who flies a runner from Iceland to Soho to bring back a certain coffee bean for him? Who’s shagging whom, who can’t get work any more, who’s getting 50 scripts a week, who’s just moved to a new production company for a signing-on fee of $2 million? Most of it’s hearsay. But we still love hearing it all.

Creatives obsess about directors. Maybe that’s because you can’t choose your account team, your client, or your CD...but you do get to choose your director. And the director has a bigger influence than anyone else on the final film.

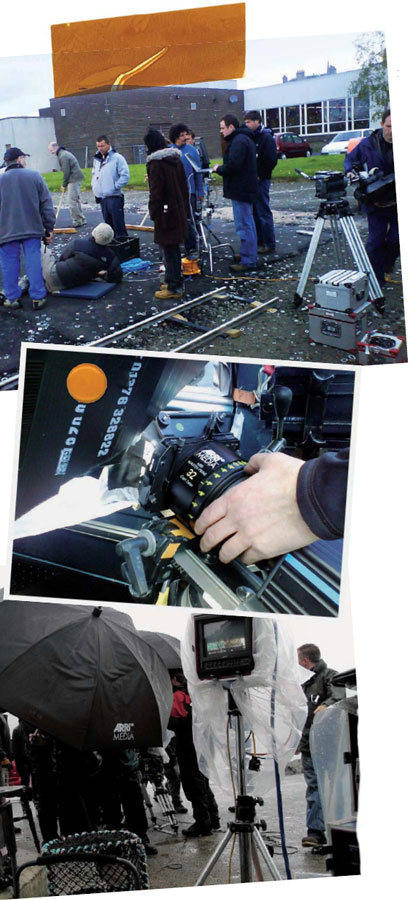

The director’s job is to take your script and turn it into a finished commercial. He will have an overall vision for how he wants the ad to look and feel, and over the course of the production, he will make hundreds of decisions that shape the commercial, including which actors to cast, which locations to shoot in, the set, how the commercial should be edited, and what music (if any) should accompany it.

Of course, you are there too, and you have a big say as well. He has to get his major decisions (e.g. casting) approved by you, and in turn you get these approved by your client. But he will make many more decisions than you do. For example, he may show you two or three locations he has in mind for the commercial, but he himself may have looked at hundreds. And in choosing the location manager, in a sense he’s already chosen the kind of locations he will be choosing from, as certain location managers might be known for finding quirky-looking settings, or edgy ones, etc.

The director is a lot more than just someone behind the camera in a waterproof jacket saying “action.” His taste and aesthetic will run through every frame of your commercial, like the DNA in every cell of a body.

That’s why the most important skill for a creative in terms of “getting the best from” directors is simply picking the right one in the first place.

The TV department keep the showreels of hundreds of directors, and they will help you pick out some who might be suitable. When looking at reels, you are basically looking for a director who is good at making the kind of ad you want to make. If it’s a dialogue-driven ad, find a director who is great at doing dialogue. If you’re looking to create an extremely beautiful piece of film, find a director with a beautiful reel.

Easy, right? Yes. In fact, it’s too easy. I hate it when creatives tell me they want an ad to be “beautiful.” That’s such a vague and generic term. There are so many different kinds of beauty—there’s the plastic beauty of a catwalk model, the rugged beauty of the coast of Cornwall, the ethereal beauty of the Northern Lights, the sinister beauty of an over-ripe pomegranate, the innocent beauty of a new-born foal…. There are endless sub-categories in every genre of commercial. Think how many different types of humor there are, or how many different types of cool. You’ll only find exactly the right director if you define exactly what you’re looking for.

Then be realistic about who you ask the TV department to contact. Martin Scorsese won’t do a tabletop ad. Don’t waste your time thinking, “But he’s never done one of those, it might be interesting for him.” It won’t.

In your shortlist of directors, always have a banker and a wild card.

The script you send to directors shouldn’t necessarily be the same as the one you send to the client. Who says it has to be? Write a special version of the script that is designed to hook a director. Leave out the lengthy product-description sequence that you put in for the client, and focus on the emotional and visual appeal of the idea. Sometimes a one-line script is all you need. For example, a director may be more attracted to a script that reads “We drop millions of colored balls down a street in San Francisco”—a script that allows him to visualize the scene in his mind—rather than a two-page lyrical description you have realized from your own imagination… and thus left him no room to use his.

When meeting directors, you need to decide “Can I work with them? Do I like them?” Over the years I’ve noticed that it doesn’t really matter if you and the director have wildly divergent personalities. As long as you have the same vision for the ad, you’ll probably get on well. But never work with jerks, however talented. It’s just not worth it. If you do fight a lot, then a) you probably picked the wrong director and b) you probably won’t end up with a good ad.

DEALING WITH TENSION

There is often tension between the director and creatives. And usually it comes from the creatives being fearful. A script—like a mathematical formula or an architect’s plan—is perfect, in the way that no finished artefact can be.

When you hand your script to a director, he will turn your perfect Euclidean geometry into rough-hewn reality. Of course, the hope is he will make it better than the blueprint. But the fear that he will cock it up is considerable.

I remember one shoot of mine where the director was so hyped-up—to avoid libel implications we might say he’d had a cup of extra-strong coffee before walking on set (it was definitely something of Colombian origin)—that he was giving each actor a ten-minute monologue of instructions for a single line of dialogue then calling “Cut” before they’d finished saying it, and then launching into another long stream of verbal diarrhea. We literally filmed less than two minutes, the whole morning.

Not much you can do when the unexpected happens. But you can at least minimize uncertainty by beating out all the questions that are on your mind before shooting starts, so you’re never sitting there on set wondering “What the hell are they doing now?”

The most tense part of the job is often the actual shoot. A lot of money is being spent in a short space of time, so people are stressed. And there’s never enough time for all the filming you want to squeeze in. That adds to the stress.

For these and other reasons, film sets can be intimidating for young creatives. But remember, it’s your ad. And though the director has ultimate power on set, with perhaps 50 people jumping to their command, if the creative says “Can we try it this other way...?”, then they have to listen. You feel strange, and guilty, as if you’re giving orders to an emperor, but sometimes it has to be done.

The question of “when to intervene” is a tricky one. My approach is that I always give the director space and let them get on and do the shot they want to do. Then if I don’t like it, I’ll explain why, and ask if they can try it a different way, either as well as or instead of. But let them do it their way first. If you’re too controlling, and don’t give them the chance to do what they want to do, then why did you hire them? There’s also a risk they can become demoralized, and just start to go through the motions.

TIPS FOR WORKING WITH A DIRECTOR

1 Respect a director’s way of working. You want to get out of them whatever they can give. So for example if they want their space, and prefer comments to be filtered through a producer, then do that.

2 Don’t tell the actors what to do—that’s what the director is being paid a lot of money to do. And actors like to hear one voice.

3 During the process of making a commercial, there is no one single way to deal with directors, because every director is different. But there will always be some way that gets a result. Sometimes it’s putting your arm around someone; sometimes it’s giving them a kick up the backside.

4 Creatives also need to shield their director, to some extent. Especially when it comes to the edit, the post-production, and everything that goes into finishing up a commercial. That’s when the account team and client can be at their most meddlesome. Be the champion of your own idea, and don’t let the forces of darkness water it down.

HOW TO GET THE BEST OUT OF ACCOUNT HANDLERS

The account handler’s basic job is to advise the client on how to move their brand forward, and marshal the agency’s resources to deliver that.

They are sometimes called account supervisors, although as well as supervising the account, they are also supervising everyone else in the agency.

They are involved at every stage of the process—discussing with the client what his communications requirements are, liaising with the planners to create a brief, liaising with the creatives as they create work to that brief, leading the selling-in of this work to the client, and then supervising the production and evaluation of the advertising. Along the way, it’s their job to solve any problems that arise.

My general advice—you have a much better chance of getting good work made if you work in partnership with account handlers, not in opposition to them.

Never shout at them, or throw laptops out of the window. Or plants. Or chairs.

Some creatives believe there’s a creeping blandness about the business that is dulling the creative edge... that the industry needs a bit of standing-on-the-window-ledge aggression from all parties, or you end up with compromised work.

But personally, I don’t believe that co-operation necessarily leads to compromise. I believe you’re actually more likely to get your way if you respect people, listen to them, and work with them to explain why your vision is the best way forward. It’s less stressful too.

At the briefing stage, don’t waste time slagging off the client or the brief. Focus on what the opportunity is, not the problems. And don’t be sullen. Ask the questions that will tease out all the vital information the account team knows, which doesn’t appear on the brief. For example, what type of work does this client like? What are they expecting for this brief? Do they have any quirks or peculiarities? These questions can yield a string of useful facts, like “Oh, Phil hates commercials with celebrities. Doesn’t think they work. But he loves animation, and…yeah—anything with dogs is a dead cert.” Now that you know to start with an animated puppy, you have saved yourself a lot of time.

Campaign, the British advertising trade magazine, once asked various industry figures: “What makes a good suit?”

The list of qualities they came up with included: patience, diplomacy, negotiation skills, ability to get bills paid on time, breadth of experience, eclectic, ability to do strategy and channel planning, helping stimulate good creative work, make things happen, drive change, clever, fun to be around, sociable, likeable,rigorous, relentless, fearless, immune to pressure, unfazed by complexity, clear vision, truth-telling, respect confidences, sense of humor, keep things in perspective, don’t try to take credit, no whinging, create, lead, manage, make it happen, be on top of everything, be ruthless, respect authority, know when you can flout convention, recognize the primacy of the idea, have a view on advertising, know everything possible about the client’s brand.

How can we expect our account handlers to have all these qualities? No one does. So, let’s not be too hard on them.

It’s a good trick to make the account team write ads to their brief before they leave your office—sometimes called “Account Man Ads.” For example, the Account Man Ad to Sony’s “Color Like No Other” brief—the brief that led to “Balls” and “Paint”—might have been “We open on a rainbow, but instead of the usual seven bands of color, it has thousands.” Not a particularly interesting idea. But it demonstrates that the brief is actually possible to answer, and tells you what the account team thinks the answer may look like.

When you have your idea, explain it as fully as you can to the account team. Talk them through the highlights of your creative journey—they will understand it a lot better if they know how you got to it.

Explain and re-explain “what the idea is.”

Make sure they understand which parts of your route are fundamental, and which are the executional details they can sacrifice if the client objects. The account team will probe your idea for weaknesses. This can be frustrating for creatives, as it sounds like they’re criticizing your work, but they’re actually role-playing how the conversation with the client might go. Play along. They might just sell your concept first time around if you prime them with a few answers to the “why” questions.

And when it comes to the production process, the best thing you can do is keep the account handler in the loop. It’s tempting not to tell them things, on the grounds that they might object, and that it takes up time talking them through it. But the more they know, the more they can manage the clients’ expectations.

Account handlers do an enormous amount of client hand-holding that is kept far, far away from the creatives. If we only knew half the sh*t they had to do... we would probably feel a lot more grateful toward them.

But, sadly, since the beginning of advertising, there has been tension between creatives and account handlers. “Our account handlers don’t know what they’re doing” or “This agency is run by the suits” are perhaps the most common complaints you will hear from creatives in after-hours pub chats.

The solution many creatives seem to have in mind to the “problem” of account handlers is for account handlers to be removed from the process, or at least made totally subservient to the creative department.

I remember one departmental meeting we had at DDB London. The usual festival of complaints about account handlers was interrupted by Larry Barker, the executive creative director. “Know one thing,” he said. “Account handlers are not going away.”

He was right. Account handlers have always been there; and always will.*

The smart thing is to learn to work with them. Let’s look at the three main causes of all the tension between us and them: they have different priorities to us, a different way of working, and different personalities too.

An account handler friend once told me the story of when a random goat was brought onto the set of a yogurt commercial. The director and creatives wanted to shoot a scene with this goat (for reasons that, alas, are no longer recalled), but since the script hadn’t mentioned a goat, and no goat had been discussed in the pre-production meetings, the client freaked out. The account handler had no clue what was going on, so it was the creatives who had to spend the next hour calming the client down and explaining what they planned to do. They did get to shoot their goat in the end, but an hour of valuable time had been lost, and they failed to get the “goat performance” that they wanted. If the creatives had shared the idea during the pre-production stage, there wouldn’t have been a problem.

*There are one or two agencies that do not have account handlers—the most notable example is Mother. However, as perhaps 99 percent of you will be working in agencies that do have account handlers, I won’t go into detail here about Mother’s system. All I will say is that if you go to Mother excited about the prospect of there being no account handlers…be careful what you wish for. It’s true there are no account handlers at Mother, but there is account handling—and it’s the creatives who have to do it. Some creatives love that, some hate it.

The tension over priorities is that creatives feel account handlers don’t care about the quality of the work, only about keeping their client happy.

And, in fact, this complaint is quite accurate.

The main priority of an account handler is not to produce great creative work.

But nor should it be. That’s your job. His main job is to keep the client happy. Sometimes that will involve producing great creative work, but only if that is what the client wants.

The different departments of an agency work together like the different parts of a car. The engine produces power; the steering wheel controls direction of travel; the oil lubricates the system. Each element has a totally different function, and each only cares about their own job…and yet that’s the best way to make a car go smoothly.

Does the engine complain “that bloody steering wheel doesn’t give a toss about power generation”? No. So neither should you complain that account handlers don’t care about great work.

DIFFERENT WAYS OF WORKING

When an account man walks into your office and you’re staring out the window, he’ll make a sarcastic comment like “Hard at work, I see.”

This is because account handlers don’t have to think of ideas; their job is talking to people and persuading them to do things. He feels much more comfortable when he comes into your office and sees you’re on the phone, or typing on your computer, because that’s what he spends his day doing.

He doesn’t realize that when you’re on the phone you are probably talking to friends, and when you’re typing on the computer you are probably forwarding a funny YouTube film to one of your mates. And it’s only when you are staring into space that you are actually doing your job—trying to think of ideas.

The biggest mystery for account handlers is why the creative floor, supposedly the heartbeat of the agency, has “no buzz.” They joke that the atmosphere is “like a library” rather than anywhere creative. What they don’t realize is that to think of an idea, you need peace and quiet.

If they make sarcastic comments about how you do your job, just ignore them.

DIFFERENT PERSONALITIES

Just as our jobs are different to theirs, the same goes for personalities. They look like us, and they talk like us, but they are not like us. Account handlers are a different species entirely.

For example, an old colleague of my wife’s (they’re both suits) once came to our house for lunch. They talked about the clients they both knew; people they had both worked with; people who had moved, been fired, promoted; creative directors they had worked with; they discussed who was easy to talk to, who was difficult to deal with, who was going through a divorce…

After they’d been talking for about an hour, I suddenly realized that neither of them had mentioned a single advert.

All they had talked about was people.

When two creatives meet up for a chat, of course we talk about people as well—who’s up, who’s down, who’s round the twist. But we will also talk a lot about advertisements. We will ask the other what they think about the latest Nike work, or Sony work, or whatever. We will talk about ideas we have had, campaigns we are working on, ads that didn’t get bought.

Our currency is advertising. Theirs is people. “Account handler” is probably the wrong term. They are really “people handlers.”

I sometimes think creatives are experts in mass communication—TV ads that aim at millions of people—while account handlers are experts in personal communication—meetings where they aim to influence the behavior of just one or two key people (i.e. clients).

Of course, they choose to exercise those skills in the world of advertising, and many of them are fascinated by adverts.

But the main reason they like working in advertising is the people. Bizarrely enough, that means you! Account handlers like working with creative people. Yes, we are frustrating and mysterious to them a lot of the time. But they enjoy the challenge. They feel it’s less boring than working in a bank or a law firm. And when it comes to working with clients, they enjoy the challenge of trying to understand that person’s needs, and persuading them that the agency has met their needs.

So, that is the most important thing to understand about our friends, the suits. They are not, as you are, focused on creating great advertising. They are focused on people, what those people want, and how to influence them.

Because dealing effectively with account handlers is so vital to your success in this business, I think it’s worth hearing an account handler’s point of view on the subject; the more you understand them, the better.

First, here is an excellent summary from Neil Christie, managing director of Wieden & Kennedy, London, on what he recommends creatives should do to get the best out of suits;

“Give them public recognition for their contribution when it’s due. Say thank you. Ask their opinion. Ask if they have any ideas about how the brief should be addressed. Ask questions about the brief that show you’ve thought about it—especially about the business issues behind the brief. Share ideas with them. Explain why you think a piece of work is right, especially when it’s “off brief.” Inspire them to feel as passionately about the work as you do. If you make them feel that you value and respect them; that you’re working together as a team, then they will move mountains for you.”

And now here’s an interview with a senior account handler at a Top Ten London ad agency, who promised to tell it like it really is…on condition of anonymity.

I can understand that it may feel that way to creatives. It’s your job to come up with ideas and, inevitably, not every single one is going to be right for that piece of business at that time, so we do have to say no quite a lot.

That wouldn’t be doing our job. We’re not just there to jump up and down clapping our hands like seals when you show us the work, you know. In reality, the client briefs us on what they want, and they expect us to get it for them. They don’t want us to bring them things they don’t want. If we did that, we would quite soon have no clients. However, we do work for the agency—the agency pays our salary, not the clients—so we’re always trying to sell the best possible work, which they will buy.

They don’t like to be painted into a corner. And they want the best chance possible of seeing work that is right. The fact is that what we do isn’t a science. There is always more than one answer. One may be more right than another, but there are always different ways to go. It’s a game of subjective judgements and the clients like to be able to participate in that judging too.

Probably not. After all, no one treats everyone the same way. There are people you like more than others and your attitude and actions towards them will vary accordingly. Friendliness and an appearance that you’re listening and being reasonable goes a long way to getting an account team on your side.

HOW TO GET THE BEST OUT OF PLANNERS

Since the dawn of advertising, there has been tension between creatives and planners. Actually, that’s not true. At the dawn of advertising, there weren’t any planners.

And that is the source of the tension. Some creatives simply feel that planners are unnecessary.

After all, advertising was conducted perfectly satisfactorily before planning was invented (the great DDB Volkswagen ads of the 1960s, for example, were created without a planner in sight).

But good planning adds a lot to the process.

Jeff Goodby, CD and co-chairman, Goodby Silverstein & Partners, told ihaveanidea.org:

“If you’ve ever gone fishing and had a really good guide, you know what the relationship between creatives and planners should be. The planner should know the river and what flies will work at what time of day. The creative people still have to make the cast and land the fish.”

Planning was invented (in about 1968) in order to provide three things: greater consumer insight; better strategies; and a focus on effectiveness.

The planner is sometimes called “the voice of the consumer” and, within an agency, the planner will know more than anyone else about the target market for a product. He will have researched it, using reams of data on purchasing patterns, and also spent time with groups of consumers.

Planners are also concerned with “effectiveness,” and planners spend a great deal of time attempting to measure the effectiveness of an agency’s campaigns, to understand what’s working and what isn’t working, and how to improve it.

But the planner’s main job is to determine the “strategy” for the creative work, a.k.a. “what to say.”

This can come as a shock to young creatives. A lot of the feedback you get on your portfolio when you’re looking for a job is about your strategies—whether they’re original, exciting, or neither. And yet as soon as you get a job, you’re no longer responsible for strategy, because the planner is. Odd.

Nevertheless, the fact that most creatives have an excellent understanding of strategy doesn’t mean you ought to ignore whatever brief the planner gives you, and write your own. Remember, the brief has been signed off by your creative director, by the head of planning, the senior account handlers on the business…not to mention the client. Some of these people may be keener on the brief than others, but they’ve all approved it. Even if the strategy you come up with is better than the one on the brief, it may take days to go around all these stakeholders and explain the new direction to them.

For all these reasons, if you ignore the brief, you are much less likely to get your work sold. You may feel that the brief is restrictive, and is preventing you from coming up with a brilliant idea. On the other hand, true brilliance entails coming up with an idea that is both wonderfully creative and on brief.

Having said all that…what if you absolutely hate the brief? First of all, don’t say it’s rubbish and you can’t work with it. Or say “uh huh” and then badmouth the planner once they’re out the door, and write to whatever you think the brief should be. Try taking the approach you’re supposed to take with your doctor: apparently, after they’ve made their diagnosis, you should ask “What else could it be?” This forces them to stop and consider other hypotheses.

If the brief is just not working for you, go ahead and talk about it. It’s not like it’s carved in stone or anything. Though it may have been signed in blood by 100 international marketing directors, in which case it will be tough to get changed. But many briefs are more flexible.

“Talk things out early,” recommends David Hackworthy, planning partner at The Red Brick Road in London. “Too many creatives are mute at formal briefing stage.”

In any case, good planners don’t just brief a creative team and then disappear. Like a good waiter, they will leave you to chew things over for a while, then come back and ask if everything is OK.

One of the best planners I’ve worked with used to come into our office every single day when we had one of his briefs. He would just sit with us and throw ideas around. He didn’t mind if we hated them. Every day he came in with a new random thought, a provocation, or a website he thought might be relevant. He was just always there...up in my grille…even though he was also the agency’s head of planning and had numerous other calls on his time. Like all the best planners, he saw his main job as being to stimulate great work.

Ultimately, a really good planner doesn’t care about the brief. They know the brief is nothing more than a roadmap. If you deliver the car to the right destination, and take a more exciting route than the map was suggesting, they’ll be delighted. And when they present your work to the client, they’ll find a way to retro-fit the brief to your work.

Creatives are often bursting with a Larry David-esque exasperation about planning. Like most planners, Russell Davies, former head of strategy at Wieden & Kennedy in London, doesn’t feel any animosity toward creatives, but he’s certainly aware of it coming his way.

Russell theorizes: “Creatives suffer so much rejection on a daily basis that they need to take it out on someone and that someone tends to be planners.” Neat argument.

As the relationship between creatives and planners is so important, I asked a few experienced planners for some advice of their own.

Russell Davies’s tip for getting the best out of planners is... “Lots of creatives see planners as a necessary evil, and most of the rest see them as an unnecessary evil. So if you’re one of the small percentage of creatives who treat them as helpful and interesting colleagues, they will be so pathetically grateful that they’ll do all sorts of helpful and interesting things for you.”

“Look up and smile when they enter the room,” adds Russell. “Don’t just continue to scowl at your computer until they’ve sat down and coughed nervously for ten minutes.”

“Demand pictures on the creative brief. Honestly, I can’t believe there are still creative briefs without pictures of the people you’re supposed to be talking to and the thing you’re supposed to be advertising. Pictures help. Refuse to do anything until they’ve given you pictures.”

“Ask them to bring you inspiration and ideas, not just instructions,” he goes on. “The brief should outline the task; the planner should help you solve it. Again, if you ask for thoughts, ideas, inspiration, and then actually listen to what they bring you, you will get tons and tons of interesting and useful stuff. Obviously a large percentage of it will be rubbish, but then a large percentage of your ideas will be rubbish, that’s the nature of things. But if you listen, and let them talk, you’ll find some unexpected nuggets in there. Things you wouldn’t have thought of on your own.”

“Get them to help you sell it. A decent planner is great at crafting an argument for a piece of creative work. Maybe better than you. They may not have been able to come up with it, but they might have more insight about why it’s great. Get them to help you put those arguments together, both inside the agency and with the client. They may have a better idea of what the client wants to hear. It’s worth running through those conversations with your planner.”

“But, basically, don’t be an ar*e. Agency life tends to push people into all sorts of weird status/hierarchy behavior. Most of it is unhelpful. You’ll get the most out of your planner if you forget all that stuff and just be nice.”

Sarah Watson, head of planning at DDB in London, says: “My tip to creatives for getting the best out of planners is...to talk to them. It’s all about the conversations. Planners have stuff in their heads that can help you. But it is only when you get talking that you come across the bits that will really unlock things for you and the way you think. Planners are a resource laid on for your benefit—don’t forget it, don’t waste it, and make sure you use it.”

Richard Huntington, director of strategy for Saatchi & Saatchi in the UK, advises: “You should demand the world of the planners you work with. Really powerful strategic ideas and briefs. At their best, a good planner is going to make sure you can’t help but produce the best work of your careers. They will do this by placing you from the very start in a territory that no other creative has visited for that brand. This is the reason you will come to depend on them and love them, not because they pop down the pub with you on a Friday lunchtime.”

However, he goes on to say: “Always remember, the reason the planner is committed to creating a better beginning for you is not to improve your reel but to make more effective work. And that’s where the rub comes. A planner’s obligation to make the work work will sometimes see you in healthy tension with them.”

Elisa Edmonds, a senior planner at Ogilvy in New Zealand, advises that “a few positive words can bring the best out in your planner.”

“We are frequently insecure,” says Elisa. “We really, really care—we want it to be great, not just good. We get nervous that our work will be savaged when it’s first presented. Any of that sound familiar? If so, you’ll know exactly how you like to be treated and know how people who get the best out of you, get the best from you.”

“Ask the planner what they looked at for inspiration when writing the brief. This might open up fresh areas for you, and provide good stuff to mull over/discuss together.”

“Be interested in what people said in research. Or what they didn’t (it’s the dog that doesn’t bark in the night that can be most interesting).”

HOW TO WORK WELL WITH CREATIVE DIRECTORS

The main job of the creative director is deciding what work the agency presents to the client.

Smaller agencies have a single creative director who is in charge of every account. Larger agencies will have several CDs, each looking after one or more clients, and above them an executive creative director, who in addition to his account responsibilities does the hiring and firing. Some CDs also write ads, some don’t.

As a creative, you mostly see the creative director in so-called creative reviews, during which he looks over the work you have done, and either approves it or suggests changes. But that is only one-quarter of his actual job. His other responsibilities include: finalizing the initial brief with the planner; talking the account team through your work; presenting your work to the client; and having endless meetings with the client about their brand guidelines, tone of voice, and the work in general. That’s in addition to meetings with the agency’s management about the work, and defining the overall creative vision for that account.

So that’s the first thing to bear in mind about creative directors—they are busy. Thus the best way to have a good relationship with your creative director is to crack his briefs quickly and cleanly. In general, creative directors most prize the teams who come up with lots of good ideas…and who don’t need much hand-holding.

“You should know that most creative directors don’t assess you simply by how creative you are,” is how David Lubars, ECD of BBDO New York, puts it. “We also consider how deep, how fast, and how willing to return to the well you are. And how much of a pain you are not.”

Of course, your CD won’t expect you to crack every brief first time. And even the simplest job will involve some to-ing and fro-ing. They say it takes two to tango, but with the number of people involved in making an advert, we could do the conga.

Everything takes time, and everything takes meetings. Try to make those meetings painless for him. Yes, ask questions. Yes, ask for guidance—that’s what he’s there for. But don’t ramble, or make long speeches about your work, and don’t argue with him or question his judgement. You may think you’re better than him. Maybe you are better than him. But for the time being, he is sitting in his chair and you’re sitting in yours.

If you disagree with something your CD says, phrase it as a question. For example, let’s say he wants you to make a headline shorter. Don’t say: “That won’t work.” Instead, ask: “Do you think it still has the same meaning, without those words?”

You’ve got to get on with this guy.

The single best predictor of success in any job is whether your boss likes you. And a creative department is no exception.

If your creative director likes you, he will spend more time with you, and you’ll learn more about what he’s looking for on a particular brief, and the kind of work he likes in general.

He may favor you with better briefs, be less likely to fire you if you under-perform, and be more likely to go along with your suggestions for photographers, directors, music, and the like.

He may even give you the benefit of the doubt when it comes to whether one of your ideas is any good or not.

Creative directors are like parents. They are in a position of immense power over their children, and it would be fairer and better if they liked them all equally, but in reality, they don’t. That’s just human nature. Out of any two people, you will always like one slightly better than the other.

Some CDs, like some parents, do play favorites. I have seen examples when a CD didn’t buy an idea that a less-favored team showed him, but when the “teacher’s pets” showed him virtually the same idea, he bought it.

Quite often, a CD will even give a team an idea. For free. This normally happens because the CD has thought of one himself, but hasn’t got time to produce the ad. So he’ll just suggest it to the first team that comes into his office. Or, more likely, to his favorites.

The sad fact is that a commitment to treating everyone equally is not a necessary qualification for being a CD.

And even the CD who is scrupulously fair-minded can’t help but be unconsciously influenced. For example, when a CD buys your ad, he will then be spending a lot more time with you, while the ad gets produced. So if you’re someone he unconsciously wants to spend more time with, he will unconsciously prefer to buy your ad rather than that of someone he doesn’t like.

Now for the really bad news: you can’t make your CD like you. (Sucking up backfires.)

This is no surprise—you can’t force anyone in the world to like you. Perhaps you’re a naturally likeable person. In which case, no problem. But perhaps you’re not—perhaps you’re shy, spiky, or surly. That still might not matter, if you have loads in common with this CD, or a similar sense of humor or way of looking at the world. But perhaps you don’t.

In the case where there is no natural mutual fondness and not much in common either, the best you can do is make an extra effort to be friendly, hard-working, responsive to his requests, diligent, thoughtful, and a good listener. In other words, you can’t make him like you, but you can make him like working with you.

HOW TO GET THE BEST OUT OF YOUR CD

So here’s how to get the best out of your CD.

On a big project, or a complex one, go and see him as soon as you’ve been briefed—before you’ve even started work.

Ask him if he has a particular take on the brief, otherwise known as “a steer.”

This can save a lot of time. He may have another campaign in mind as a tonal reference. He may already have an idea of his own. Also, don’t forget to ask what he thinks would be wrong for this brief. Knowing what not to do can save you lots of time.

While you’re working on the brief, try to get as much time with him as you can.

In addition to any scheduled reviews, pop in for an informal chat or two. The more time you spend with him at this stage, the better idea you’ll have of what he’s looking for.

I’ve already covered how to present to the CD in Chapter 5, but there’s more to a successful review than presenting your work well. The main skill you will need is listening.

Every CD loves the sound of their own voice; the more you listen to him, the more he will think what great company you are. Plus, if you listen hard enough, he may tell you how to crack the brief. If you throw in the occasional insightful question, he may even crack the brief for you himself, “live.”

If he asks you to do something specific for the next review, do it.

If you don’t think it works, do something else as well—something better—but if you haven’t at least done what he asked, he may get cross.

Don’t argue. For some reason, it’s a defining characteristic of CDs that they do not change their minds if you argue with them. That doesn’t mean you can’t get your way—far from it—but you just have to be subtle. An example of the wrong thing to say would be “Well, the account team agrees with us” or “This is our ad and we just want to do it the way we want to do it.”

Most CDs are control freaks and you have to make it look as if you are doing what he says. Even if you’re not.

Let’s take a common situation. You crack the brief early on, you know your idea is perfect for the brief, and the account team thinks so too, but for whatever reason, the creative director blows it out. What you do is wait until the client is screaming out for something, then you go back into the creative director, having made a few minor tweaks to your work, and tell him: “Look, we took on board your comments about this, we’ve made a few changes, and we were wondering whether you think it works now?” He can then approve it, thinking it was his input that saved the day.

Get to know each individual CD’s style. Don’t ask him directly “what his style is” because no one likes to think they have one. But they all do. Some CDs go for highly rational work, for example, and some prefer a more emotional approach.

The better you know your CD’s tastes, the more work you will sell to him.

After whether your CD likes you, the next most important factor is whether he is any good.

A good CD makes a massive difference. Some CDs consistently get great work out, whatever the agency, whatever the client. It’s no coincidence that the world’s top CDs are paid five, ten, or 20 times what the average creative earns.

But if you happen to have a bad CD, the situation is not lost. After all, you can still come up with great work. It’s just more of a challenge to get him to buy it.

HOW TO HANDLE THE DIFFERENT TYPES OF BAD CD

Here are some different types of bad CD, and how to handle them:

In general, if you have a bad CD, who doesn’t like you, then you need to get another job as soon as you can.

If you have a good CD, who also likes you…then you are in a rare and happy position.

Hang on to it.

HOW TO GET THE BEST OUT OF PHOTOGRAPHERS AND ILLUSTRATORS

Advertising photographers have a great life. They normally ride a motorbike, and live/work in an enormous wood-floored studio in the trendiest part of town. For most of the year, they work on personal projects, like photographing the glaciers in Iceland, or gang culture in East L.A. And occasionally, they take photographs for advertisements.

The “occasionally” part is a problem. There are thousands of photographers out there. Even more than there are directors.

That’s a big problem for them, because a lot of photographers don’t get much work. And it’s a problem for you too, because you have thousands of photographers to choose between.

Even more so than with directors, the most important aspect of getting the best result from a photographer is choosing the right one in the first place.

If your agency has an art buying department, or a head of art, make full use of them. In some agencies, it’s compulsory for art directors to see the head of art and get his input before choosing a photographer. In most agencies, the system is less formal, but I would strongly recommend getting to know your head of art, and art buying department. The good ones have an encyclopedic knowledge of photographers and illustrators. Show them your layout, and ask who they would recommend for the job. Often, they’ll give you a complete gem, and make you look like a genius. If you don’t agree with their recommendation, you’ve lost nothing.

As a general rule, work with the most talented and experienced people you can. But don’t be afraid to occasionally take a risk with untried talent—it could make your ad look more distinctive.

Choose a photographer on the strength of what they’re good at. Sounds obvious, but art directors often choose a photographer because they love their work and then make them do something entirely different.

Some photographers and illustrators like to present themselves as good at lots of things, but this is an illusion. Every photographer has an essence to their work. If you’re an art director, gaining a good working knowledge of these artists and their styles is a vital part of your job.

See photographers’ reps when they call. Ask your art buyer regularly to show you interesting new work. Look at photography and illustration in magazines (editorial and ads) and find out who did them. Photocopy your favorites and keep them in a scrapbook. Go to galleries. Trawl the internet for interesting stuff and claim that you’re working.

Nowadays, every photographer and illustrator has their portfolio online. Keep up with image-makers’ websites, and know where people’s heads are at.

“Don’t get somebody to do what they did ten years ago,” advises Mark Reddy, head of art at BBH in London.

“Get people doing what they want to do, as well as what you want to do.”

Really study their portfolios and websites. Work out exactly what each does best and match that to what you want for your concept.

Don’t be lazy and pick someone you’ve heard of, or who has just won an award. (Though if you do end up working with a famous photographer or illustrator, don’t be overawed. Remember, it’s a partnership.)

DON’T TYPE-CAST

Try not to fall into the trap of type-casting (e.g. getting a famous car photographer to do yet another car shoot). You can often get interesting results by not going with the obvious choice.

In fact, it’s a classic laziness to choose someone who has shot a similar subject before. Don’t worry too much about subject matter. In other words, if your ad features a horse on roller skates, there’s no need to find a photographer who has previously shot roller-skating equines.

By understanding that a photographer’s style is about more than his subject, you can make more exciting hirings: using a jewelry photographer to shoot a car, because they will make it look like an exquisite high-fashion item, for example.

The most important thing to look for in a photographer’s book is a tone of voice that matches what you want for your ad. If you want your ad to be funny, look for a photographer who does funny. And again, narrow down as much as possible what kind of funny you want. Do you want surreal humor? Slapstick humor? Understated humor? There are so many photographers out there, the more you can decide in your own mind what you want, the more likely you are to find the perfect match.

A good match is vital. There’s nothing more futile than trying to change a photographer’s style to match your idea. It’s the cause of a huge amount of friction between agency and client. Be honest about what the client needs, what your idea is about, and what the photographer or illustrator is best at; don’t try to mash them together.

When you’ve got the right horse, the riding’s easy. He won’t try and go anywhere you don’t want to go, and you won’t have to use the whip.

Actually, the relationship between creatives and photographers (or illustrators) tends to be a lot less fraught than the relationship with directors. Perhaps it’s because less money is being spent, so each job is less pressured. Perhaps it’s because photographers tend to be more laid-back characters than directors.

If you’ve spent plenty of time talking about the job beforehand, then at the actual shoot you’re just there as a fail-safe. One or two well-known art directors (Dave Dye, for example) don’t even go on shoots.

“Have the confidence to stand back and let the illustrator/photographer get on with it,” advises Grant Parker, head of art at DDB London. “Trust what they do, trust their talent. There is no point in commissioning someone, and then being too prescriptive about how they should do it.”

“I prefer being able to give a photographer/illustrator a slightly looser brief so that they will come back with something a bit unexpected,” he adds.

The trick is to strike the right balance between giving them a clear and accurate brief of what you want them to do, and leaving them enough creative freedom to add something of their own. This will keep them motivated, and hopefully get you a better image than you could have come up with by pressing the camera shutter yourself.

Leaving room for experiment often leads to happy accidents and surprising results. Which of course leads to more memorable ads.

“Don’t have a preconceived notion of what you want the picture to look like,” agrees Mark Reddy. “The act of creating anything is a journey. Be open to let the idea develop.”

Running a photography shoot is less complex than running a film shoot. There’s often no client or account team there. (Slight watch-out—no client on the set means you have to deliver a shot that conforms to the agreed layout, in addition to any other directions that might emerge over the course of the shoot.)

But in general, the same principles apply. Let them do what they want to do—what you hired them for. Only if they are going wrong should you intervene. Hanging back a bit will also give you some mental space, which allows other ideas to improve the shot to occur to you.

Most art directors really enjoy working with photographers and illustrators—it’s often the bit of the job they like best. They enjoy actually making something; there’s a real pleasure in the physicality of the process.

For the duration of the job, the art director is a patron, a collaborator, a fellow artist, and crucially… out of the office.

Get what you want from photographers by using a combination of charm, positive encouragement, enthusiasm, and appearing to compromise.

Be willing to bend on the things that aren’t important—this buys you the right to stand firm on things that are.

“Disagreements and heated arguments are unnecessary,” claims Paul Belford. “I simply say ‘let’s try it both ways’.”

HOW TO GET THE BEST OUT OF TYPOGRAPHERS

For some reason, advertising agencies have decided that for film, the process involves going to an outside specialist—an external production company. But with print, it’s nearly always done in-house.

In some smaller agencies, the art directors design the ads themselves.

In the larger and better agencies, there is a specialist studio, design, or typography department, whose responsibility it is to turn a photograph or illustration into a finished advertisement—deciding how to treat the image, selecting type for it, and bringing these elements harmoniously together.

There’s some advantage to working with a pool of people that you know well. But the geographical closeness has a disadvantage too.

According to Mark Reddy, “The designers get seen as plumbers who just do what they’re told.” Plus “sometimes there are about 16 people around a monitor. Nothing can get done then. And anyone in the agency can come up and sit on their shoulder…account handlers, planners, anyone…and make a comment.”

Therefore, one of the roles of the art director is to protect the designer.

In general, the relationship between an art director and the studio tends to be rather good. After all, there’s so much common ground. The studio guys are normally people who love great images and good design, just like art directors.

(For some reason, designers are nearly always into music too. It’s almost impossible for some of them to even begin working on a design until they have selected the correct iTunes playlist to accompany it.)

Most designers are cool, laid-back people that art directors find easy to get along with. But design is subjective. In a studio that employs several designers, you are bound to prefer the work of some over others.

So once again, the best way to get the best out of your studio is to pair your job with the right designer in the first place. Some in-house guys are jacks-of-all-trades, so their personal style won’t either particularly benefit or fight with your project. But some will have their own style.

Some will be the hip ones, into funky ways to use type, or outrageous ways to crop an image. Others will obsess over every detail, and produce tightly controlled layouts. Find the one who’s right for your job. You will soon get to know this. But if you’re a new art director or new to the agency, ask for advice from your traffic person or the head of the studio.

AN ASSIGNED TYPOGRAPHER

If you don’t have a choice, but instead your job is “assigned” to a typographer, then you need to behave differently according to whether you have been assigned to a good typographer, or a not-so-good one.

Put simply, you give the good typographer more freedom—a clear brief, but which is wide enough to allow them to add their own input. Ask them for their own ideas too. With the weaker typographer, you’ll have to be very specific about what you want. They won’t add anything to your idea, but even the less creative typographers should be able to competently execute your thinking, and as long as you don’t expect them to add any of their own, you can still be satisfied with their work.

Actually, it’s important in general that you don’t confuse a designer with an art director. It’s not their responsibility to come up with an overall art direction idea for an ad; it’s yours.

AND GIVE THEM TIME...

Some art directors make the mistake of going into the studio too early.

“Whatever you do,” says Paul Belford, “don’t just hand over a scrap of paper with a scribble on it and say: ‘Do something interesting with this please’.”

Even if you know the style you want, say for example you want something “cool” for an ad promoting your city’s night bus service, don’t brief your designer to “do something cool.” That’s a dreadful brief. It’s too wide. You need to have an idea first, for example, if you are trying to make the night bus a cool mode of transportation for young people, you might have the idea of art directing your ad like a nightclub flyer.

Then you need to find lots of reference for that. Allow time for the designer to find some too. Now he can riff off your idea, produce multiple styles of flyer, and the two of you can work out how the idea works best.

“If you absolutely have to follow some turgid brand guidelines, be up-front about it,” advises Paul Belford, “so you don’t waste time.”

Time is vital. Give your designer as much of it as you can—don’t expect something brilliant in an afternoon.

And as far as the final result goes, “have an open mind and be prepared to be shocked,” says Belford. “If you’re shocked, consumers will also be shocked. You want your work to get noticed, don’t you?”